Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Black Illegal Illicit Trade

Uploaded by

Abbas KhanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Black Illegal Illicit Trade

Uploaded by

Abbas KhanCopyright:

Available Formats

A Theoretical Analysis of Smuggling

Author(s): Jagdish Bhagwati and Bent Hansen

Source: The Quarterly Journal of Economics , May, 1973, Vol. 87, No. 2 (May, 1973), pp.

172-187

Published by: Oxford University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1882182

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

The Quarterly Journal of Economics

This content downloaded from

206.84.141.40 on Wed, 23 Aug 2023 19:28:06 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

A THEORETICAL ANALYSIS OF SMUGGLING *

JAGDISH BHAGWATI

AND

BENT HANSEN

I. Smuggling and welfare, 173.- II. Exogenously specified objectives:

target increase in importable production, 184. -III. Overinvoicing and under-

invoicing of transactions, 186. -IV. Conclusions, 187.

In some underdeveloped countries smuggling takes on large pro-

portions and is a major economic problem. In Afghanistan as much

as one quarter to one fifth of total foreign trade is believed to be

smuggling trade.1 Other countries in the East, certainly Indonesia,

and a number of African countries also have this problem. There is

a need, therefore, to look at smuggling not only as a moral and legal

problem but also as a purely economic phenomenon.

It is commonly argued that smuggling must improve economic

welfare since it constitutes (partial or total) evasion of the tariffs

(or quantitative restrictions), which, for a small country, would

signify a suboptimal policy. We propose to demonstrate in Section

I of this paper the falsity of this view, while also investigating the

restrictive conditions under which smuggling may improve welfare.

Since, however, the tariff may be, and often is, levied to achieve

specific objectives, such as protecting import-competing production

or collecting revenue, we should also want to compare the welfare

levels reached under tariffs with and without smuggling, subject to

such exogenously specified objectives. In Section II we do this for

the case of protecting production and show that the achievement

of a given degree of protection to domestic importable production,

in the presence of smuggling, produces lower welfare than if smug-

gling were absent. In Section III, we extend our analysis to the

phenomenon of faked invoices.2

* Helpful comments were received on anearlier draft of this paper from

Abba Lerner, Earl Rolph, Murray Kemp, and Ernest Nadel. Bhagwati's

research has been supported by the NationalScience Foundation.

1. B. Hansen, Economic Development in Afghanistan: An Appraisal

(submitted to Secretariat of United Nations ECAFE, Bangkok, 1971); H. H.

Smith et al., Area Handbook for Afghanistan (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Gov-

ernment Printing Office, 1969).

2. Alan Manne has called our attention to an early attempt to analyze

smuggling by the famous Italian eighteenth-century (1738-1794) criminologist

and economist Cesare Bonesana, Marchese di Beccaria (Cesare Beccaria, "Tenta-

tivo Analitico Sui Contrabbandi," Estratto dal foglio periodico intitolato: il

Caffe6 (Vol. I, Brescia, 1764-65); reprinted in Scrittori Classici Italiani di

This content downloaded from

206.84.141.40 on Wed, 23 Aug 2023 19:28:06 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

A THEORETICAL ANALYSIS OF SMUGGLING 173

I. SMUGGLING AND WELFARE

In the following analysis, we apply the Hicks-Samuelson value

theoretic framework, which is customarily used in the traditional

theory of international trade. We further assume that primary

factors, in perfect competition, produce (two) traded goods and that

the country is small - i.e., the terms of trade are fixed. We shall as-

sume a given, well-behaved community indifference map. This as-

sumption could be given up without altering any conclusions: it is

retained only for convenience of exposition.

Since smuggling merely represents, from a welfare point of view,

yet another way in which exportables are transformed into import-

ables, we must represent it as a smuggling transformation (or offer)

curve. However, it is clear that this transformation curve must be

less favorable than the terms of trade.

We next have the option of assuming that smuggling is either

competitive or monopolistic and that the smuggling offer curve is

Economia Politica, parte moderna, tomo XII, Milano 1804, pp. 235-41). Bee-

caria's problem seems to be to find a method for rational determination of

tariff rates and for that purpose he sets up a condition for smuggling to break

even. Beccario does not explain his symbols very precisely, but there can be

no doubt that the following interpretation is correct.

Assume that a merchant's investment in merchandise is u and that

the tariff duty to be paid thereon is t. The rate of tariff is thus rT t/u. With

smuggling the value of the merchandise successfully brought through the con-

trols without payment of tariffs is x. Thus (u-x) has been confiscated. Since

the successfully smuggled commodities may be sold at domestic market price,

the condition for smuggling to break even is clearly x(1+r) =u, or, as Beccario

presents it, x+tx/u=u. He then develops this expression into something that

perhaps can be described as isoprofit curves, but does not get anywhere with

his analysis, and finally expresses the hope that it may prove useful as a

starting point for further analysis.

It is, indeed, easy to develop Beccario's analysis. Let p denote the smug-

gler's total profit. We then have p=x(+?r)-u. Let p/u=r be the rate of

profit and x/u=z be the probability for success in smuggling. We have then

immediately 1+r=z(l+r). Assume now that the "normal" rate of profit is

r*. For smuggling to be unprofitable the tariff rate has to be set so that

1+r*

T< -1. If, on the other hand, the sovereign can work on the probability

of successful smuggling through increased supervision -the more supervision,

the lower is z -our relation shows the trade-off between increased supervision

and increased tariff rates (revenues). To judge from his text it was precisely

this trade-off that Beccario was looking for -natural for a criminologist.

From a national point of view commodities are not lost because they

are confiscated, of course. Nonetheless, Beccario's analysis introduces a pri-

vate cost factor, the risk of being caught, that certainly is important for de-

termining the volume of smuggling and that our analysis does not deal with.

(Pierluigi Molajoni translated Beccario's article and has helped us with the

interpretation.)

3. As James Kearl has remarked to us, however, there may be relatively

minor instances of smuggling at more favorable terms of trade-as when

LDC-resident Americans with subsidized PX sources of foreign goods may be

willing to resell these goods in their host-LDC's at prices that fall below legal

channel prices.

This content downloaded from

206.84.141.40 on Wed, 23 Aug 2023 19:28:06 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

174 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

characterized by either a constant rate of transformation or an in-

creasing rate of transformation. We consider all these options in the

following analysis.4 For the sake of simplicity we shall assume

that the individual smuggler has a constant marginal rate of trans-

formation. When we assume increasing marginal rates of trans-

formation for the smuggling industry as a whole, we retain the

assumption of individual constant rates of transformation. The

industry's increasing rate of transformation is thus exclusively due

to intra-industrial, interfirm diseconomies of scale. This assump-

tion permits us in a simple way to deal with both perfect competi-

tion and monopoly without loss of generality.

With perfect competition in smuggling, both the foreign price

(the terms of trade) and the domestic price are given to the indi-

vidual smuggler. With monopoly in smuggling, however, several

possibilities are open. We shall use a minimum assumption to the

effect that, whereas the monopolistic smuggler knows and takes

into account the form of the (smuggling) industry's transformation

curve, he does not consider the effect on domestic prices of a change

in the volume of smuggling.5 We have in fact also studied the case

in which the monopolistic smuggler does consider domestic price

effects. But our conclusions remain valid in this case as well. Hence,

for reasons of space, we do not present this analysis here. More-

over, we cannot possibly take up here all possible cases of imper-

fect competition.

We also assume that, in the monopolistic smuggling case, the

smuggler is a "nonresident" whose profits therefore do not constitute

welfare for the country that experiences smuggling.6 The question

of the residence of the smuggler clearly does not arise, however, in

the case of competitive smuggling; for, under our assumptions, the

smuggling profits under competition would be zero.7

4. We disregard the petty smuggling of tourists that is done at zero mar-

ginal costs (economically). Our concern is large-scale smuggling on a com-

mercial basis.

5. At constant costs our monopolistic smuggler clearly behaves in exactly

the same way as a competitive smuggling industry would do. And at increas-

ing costs he behaves as a competitive smuggling industry does at increasing

costs for the individual smuggler without intra-industry diseconomies.

6. We could assume that the smuggler is a resident of the country or,

which is very realistic in some primitive countries where smuggling is a large

industry, that the smugglers really belong to no country. In Afghanistan

nomadic tribes move across the borders to and from Pakistan and Iran, and

some of them make a living from smuggling (Smith, op. cit., pp. 328 ff.). They

are "countries without fixed territory." Either country, or both, may include

the nomads in their population and national income estimates, but such

statistical conventions do not integrate the nomads with either country!

7. We should clarify, however, that the results for the monopolistic

This content downloaded from

206.84.141.40 on Wed, 23 Aug 2023 19:28:06 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

A THEORETICAL ANALYSIS OF SMUGGLING 175

Perfect Competition in Smuggling at Constant Costs

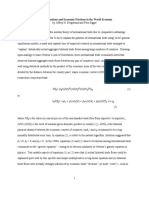

In Figure I, AB is the production possibility curve and the slope

of PfCf (= the slope of PtCt) is the fixed, international terms of

trade. The domestic price, inclusive of the tariff but in the absence

of smuggling, is tangent to AB at Pt. If free trade prevailed, welfare

would be at Uf, whereas with the tariff, but without smuggling

would be at Ut.

With smuggling, however, the smuggling transformation curve

is PC, (steeper than PfCf, but less steep than the tangent at Pt);

the domestic price faced by producers and consumers is PC,, and

the welfare is U,.

Since U8 < Ut, we have here a case where smuggling has reduced

welfare below what it would be in the absence of smuggling. Smug-

gling becomes a welfare-reducing phenomenon, contrary to common

belief.

On the other hand, Figure II depicts a case where U,> Ut:

smuggling has improved welfare. We can therefore conclude:

For nonprohibitive tariffs, and constant costs smaller than the

tariff-included price and perfect competition in smuggling,

smuggling cannot be uniquely welfare-ranked vis-a-vis non-

smuggling.

The rationale underlying this conclusion is readily seen by anal-

ogy with the analysis of the welfare effects of a trade-diverting

customs union. Smuggling is analogous to admitting a "partner

country" as an importer at higher cost than the "outside country";

smuggling therefore imposes a terms of trade loss, but the production

and consumption gain may outweigh this loss, as they do in Figure

II, but not in Figure I. Thus, we cannot tell in general whether

smuggling is welfare-improving or not-compared to legal trade

with the tariff.8

smuggling case, showing that smuggling may be harmful, do not critically de-

pend on the assumption that the smuggler is a nonresident. While it may be

thought that the country must be worse off from the exercise of monopoly

power from abroad, it must be remembered at the same time that the monopo-

list smuggler maximizes along an "inferior" transformation curve and not

along the "legal" offer curve.

8. We might add, however, that, if we were to draw the tangent to the

production possibility curve AB and the no-smuggling tariff situation utility

curve Ut in Figures I and II, and define the point of tangency with AB as P-

we can distinguish two zones (in analogy with the trade-diverting customs

union theory): Zone I, defined as the range of smuggling offers that would

yield smuggling situation equilibrium production between Pt (excluded) a

Pz (excluded), where the smuggling must necessarily improve welfare over the

nonsmuggling situation; and Zone II, defined similarly over the range from

P, (excluded) to Pt (included), where the smuggling must necessarily worsen

welfare.

This content downloaded from

206.84.141.40 on Wed, 23 Aug 2023 19:28:06 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

176 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

Y-EXP

0 B X-IMP

To~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~o

FIGURE I

Perfect Competition in Smuggling at Constant Costs

With free trade, production possibility curve AB, and given international

price line PtCr, the welfare (maximum) is at U,. With tariff, the producti

consumption, and welfare are at Pt, Ct and Ut, respectively, provided that no

smuggling takes place. With smuggling, at constant price line (transforma-

tion line) P8C,, less steep than the tangent to AB at Pt, legal trade ceases and

welfare ends up at U,<Ut. Hence, smuggling reduces welfare.

In both Figures I and II legal trade is eliminated, given the

assumption that the smugglers' transformation line is less steep than

the tangent to the country's production frontier at Pt; when the

competitive smugglers' costs are constant and lower than the tariff-

included price, legal trade cannot survive.9 Were the smugglers'

transformation line steeper than the tangent at Pt, smuggling would

on the other hand, cease completely, and legal trade prevail. But

there is here a borderline case in which smuggling and legal trade

may coexist. When the smugglers' transformation line coincides

with the tangent at Pt, smugglers' constant costs are equal to the

tariff-included price and smuggling may or may not prevail. Un-

fortunately our assumptions leave, strictly speaking, the division

9. John Pettengill has remarked to us, however, that governmental

agencies may be compelled to buy through legal channels, in which case

legal imports at higher cost could coexist with illegal imports by the nongov-

ernmental sector at lower cost. We exclude this possibility in the analysis in

the text.

This content downloaded from

206.84.141.40 on Wed, 23 Aug 2023 19:28:06 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

A THEORETICAL ANALYSIS OF SMUGGLING 177

Y-EXP

A \S

Uf

0 B X-IMP

FIGURE II

Perfect Competition in Smuggling at Constant Costs (cont.)

This figure is identical with Figure I, except that now smuggling im-

proves welfare: U,>Ut. With the smugglers' transformation line less steep

than the tangent at Pt, legal trade is again eliminated.

of trade between smuggling and legal trade indeterminate. Never-

theless, we can state unequivocally that in this case smuggling must

be a welfare-reducing activity. Figure III shows that no matter how

much or how little smugglers trade, trade exclusively on a legal

basis would be better. If the smugglers have all trade, as at point

C8 at welfare level Us, Ct at the welfare level Ut must clearly be

better: Ut> Us. And with smuggling at Q and legal trade at Cs, t, we

have Ut> U8, t. We have thus the following result:

For nonprohibitive tariffs, and constant costs equal to the tariff-

included price and perfect competition in smuggling, legal trade

and smuggling may coexist. In this case, no smuggling is better

than any amount of smuggling; and the less smuggling, the

better.

Perfect Competition in Smuggling at Increasing Costs

We now consider the case where there are increasing costs in

smuggling, while it continues to be competitive. It is clear that, in

this case, we can have smuggling coexisting with legal trade, whereas

in the preceding case, with constant costs in both smuggling and

This content downloaded from

206.84.141.40 on Wed, 23 Aug 2023 19:28:06 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

178 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

Y-EXP

A U

Cs Ut~~C U

us us t Ust

0 B X-IMP

FIGURE III

Perfect Competition in Smuggling at Constant Costs (cont.)

In this figure, the smugglers' transformation line, P, C,, coincides with

the tangent to AB at Pt (=P,). If the smugglers have all trade, the welfare

level will be U, with the consumption point C,. C, is clearly inferior to Ct;

therefore U,<Ut. With smuggling at Q, legal trade will lead to the consump-

tion point C,, t at welfare level U,, t. We have always U,<U,, t<Ut. The

first inequality is obvious; it means that some legal trade is better than no

legal trade. The second inequality follows from the circumstance that, if

Ut<U.,, which is easily seen to be possible, there would exist at least one

more equilibrium point on the trade line, PtCt, at a higher welfare level

than U,, t (J. Bhagwati, "The Gains from Trade Once Again," Oxford Eco-

nomic Papers, XX (1968), 137-48).

legal trade, smuggling, if profitable at all, eliminated legal trade

apart from a special borderline case. This possibility of legal trade

coexisting with smuggling is not merely a theoretical curiosum: in

real life it is probably the most common case, and, as we show be-

low, it turns out to be critical to the welfare effects of smuggling

(indeed, as we have already seen in the borderline case above).

Let us initially discuss the cases where smuggling eliminates

trade, despite increasing costs. Figure IV illustrates this possibility.

The smuggling transformation curve, PCs, now exhibits diminish-

ing returns, and the equilibrium under smuggling shows the domestic

price ratio, at which production and consumption take place, to be

This content downloaded from

206.84.141.40 on Wed, 23 Aug 2023 19:28:06 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

A THEORETICAL ANALYSIS OF SMUGGLING 179

Y-EXP

Aus ~ s Ut Ut

0 B X-IMP

FIGURE IV

Perfect Competition in Smuggling at Increasing Costs

This figure is identical with Figure I, but we now have increasing costs

in smuggling. The transformation curve for smuggling is PCS, and the

equilibrium for the smuggling situation is characterized by production at P,,

where the average (recall the assumption of individual constant rate of trans-

formation) transformation rate in smuggling (the straight line, PSCS) is tan-

gential to AB and by consumption at C,, where the same rate is tangential

also to Us. Again, legal imports are eliminated, and U8<Ut.

the line PC8. Since PC, is steeper than the legal trade price l

P1Cf, legal trade has been eliminated. Smuggling is shown to

welfare vis-a-vis the nonsmuggling situation: U8 < Ut.

On the other hand, Figure V shows just the opposite: Ut < U,

and smuggling has improved welfare. Thus, we have the following

result:

For nonprohibitive tariffs, and increasing costs and perfect com-

petition in smuggling, smuggling cannot be uniquely welfare-

ranked vis-a-vis nonsmuggling when legal trade is eliminated

by smuggling.

Consider, however, the case where legal trade is not eliminated

in the smuggling situation. Figure VI, which is variant on Figures

IV and V, illustrates this case. In the smuggling situation, the do-

mestic price will now be the tariff-inclusive price: so both produc-

tion (at P,) and consumption (at C8) must be at tariff-inclusive

This content downloaded from

206.84.141.40 on Wed, 23 Aug 2023 19:28:06 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

180 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

Y-EXP

Uf~~~~~~~~~U

S uus

0 B X-IMP

FIGURE V

Perfect Competition in Smuggling at Increasing Costs (cont.)

This figure is identical with Figure IV, except that we now show smug-

gling to result in greater welfare than legal trade: U,>Ut. Again, in the

smuggling situation, legal imports are eliminated.

prices. The point of trade on the smuggling transformation curve,

PSQS, must be (at Q) where the average terms of trade (we have in

dividual constant returns) are again the same as the domestic price

ratio. However, legal trade must occur at the international price

ratio, the slope of QC,. It is clear, then, that smuggling worsens

welfare, and we thus have the result:

For nonprohibitive tariffs, and increasing costs and perfect

competition in smuggling, when legal trade is not eliminated,

smuggling necessarily reduces welfare vis-a-vis the nonsmug-

gling situation.

The rationale for this result is again readily seen. The smug-

gling situation, vis-a-vis the nonsmuggling situation, now imposes

identical production and consumption distortions on the economy,

while also imposing a terms of trade loss; smuggling must therefore

necessarily be a welfare-reducing phenomenon in this instance.

Monopoly in Smuggling at Constant Costs

When smuggling is monopolistic, the marginal rate of trans-

This content downloaded from

206.84.141.40 on Wed, 23 Aug 2023 19:28:06 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

A THEORETICAL ANALYSIS OF SMUGGLING 181

Y-EXP

0 B IMP

FIGURE VI

Perfect Competition in Smuggling at Increasing Costs (cont.)

This diagram shows a situation where smuggling and legal trade coexist

in equilibrium. The production points, Pt and P8, therefore coincide; smug-

gling takes the availability point to Q and legal trade takes it then, at inter-

national prices, to C, and welfare U8<Ut (the welfare that would be achieved

under legal trade alone); see caption for Figure III concerning the possibility

of U,>Ut, in case of multiple equilibria.

formation in smuggling will be equated with the domestic price

ratio. However, for constant costs in smuggling, the marginal and

average rates of transformation are identical, and hence the results

are identical with the case where smuggling is competitive. Hence

we can conclude:

For nonprohibitive tariffs, and constant costs and monopoly

in smuggling, smuggling cannot be uniquely welfare-ranked

vis-&-vis nonsmuggling.

Monopoly in Smuggling at Increasing Costs

However, when there are increasing costs in smuggling, we

have to distinguish between marginal and average terms of trade in

smuggling. As with the competitive case, we find that the ranking

of smuggling vis-h-vis nonsmuggling is critically dependent on

whether smuggling eliminates legal trade.

This content downloaded from

206.84.141.40 on Wed, 23 Aug 2023 19:28:06 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

182 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

Y-EXP

Monopoly in Smuggling at I

us

0 BX-IMP

FIGURtE VII

Monopoly in Smuggling at Increasing Costs

This figure is similar to Figure V: legal trade is eliminated and U,>Ut.

However, instead of depicting smuggling on the perfectly competitive assump-

tion, we now equate the marginal rate of transformation in smuggling (at C.)

with the marginal rate of transformation in domestic production and domestic

prices (at Ps). Smuggling improves welfare over the legal trade situation.

In Figure VII, we illustrate a case where smuggling does elim-

inate legal trade. The difference from Figure V, where the case of

competitive smuggling under increasing costs was discussed, is that

the smuggling equilibrium is characterized by equality of domestic

prices and the marginal rate of transformation in smuggling -the

tangents to the production possibility curve AB at PF, to the trans-

formation curve P8S at CQ, and to the social indifference curve U8

at C, are parallel. We here depict a case where Us> Ut: smuggling

is welfare-improving. We could, however, equally readily have re-

drawn the diagram to show U8 < Ut - i.e., that smuggling had re-

duced welfare.

We thus have the following proposition:

For nonprohibitive tariffs, and increasing costs and monopoly

in smuggling, smuggling cannot be welfare-ranked vis-a-vis

nonsmuggling when legal trade is eliminated by smuggling.

We note, therefore, that the conclusions are identical regardless

of whether smuggling is competitive or monopolistic.

This content downloaded from

206.84.141.40 on Wed, 23 Aug 2023 19:28:06 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

A THEORETICAL ANALYSIS OF SMUGGLING 183

Consider now, however, the case where smuggling fails to elim-

inate legal trade. Figure VIII illustrates this case. As with the com-

Y-EXP

0 B X-IMP

FIGURE VIII

Monopoly in Smuggling at Increasing Costs (cont.)

This diagram shows the simultaneous presence of smuggling and legal

trade in equilibrium. It is easy to see that, in this case of continued legal

trade in the presence of smuggling, smuggling is necessarily inferior to non-

smuggling: Ut>U8. Concerning the possibility that Ut<U8, in case of multiple

equilibria, see caption to Figure III.

petitive smuggling case, we find that U8 <Ut and that smuggling

necessarily reduces welfare. Again, it is easy to see why: with legal

trade continuing, the distortion in domestic production and con-

sumption must be identical between the smuggling and nonsmug-

gling situations, whereas the presence of smuggling imposes an (ad-

ditional) terms of trade loss. Thus we can conclude:

For nonprohibitive tariffs, and increasing costs and monopoly

in smuggling, smuggling is necessarily inferior to nonsmug-

gling when smuggling does not eliminate legal trade.

Prohibitive Tariffs

Note, however, that we have explicitly qualified all our propo-

sitions by stating them as valid for nontprohibitive tariffs alone. The

reason for this is clear enough. When we consider a prohibitive

tariff, the nonsmuggling situation is autarkic. Smuggling then

This content downloaded from

206.84.141.40 on Wed, 23 Aug 2023 19:28:06 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

184 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

makes trade feasible; the appropriate analogy now is with a trade-

creating customs union, as distinct from a trade-diverting customs

union, and clearly gains must necessarily accrue from smuggling.

We can thus conclude:

For prohibitive tariffs, smuggling is necessarily superior to

nonsmuggling, whether smuggling is competitive or monopolis-

tic, and whether subject to constant or increasing costs.

Perfect Competition vs. Monopoly in Smuggling

A comparison between Figures VI and VIII leads directly to the

conclusion:

When legal trade and smuggling coexist at nonprohibitive tariffs

and increasing costs in snuggling, monopoly in smuggling is

better than perfect competition.

In other words, the more smugglers we put in jail, the better!

This sounds quite reasonable and proper: economics and morality

coincide in their prescriptions! (When legal trade is eliminated,

however, monopoly and competition cannot be ranked thus. And at

constant costs the two are identical (on our assumptions).) Our re-

sult is analogous to the familiar proposition in optimum tariff theory

that the exercise of monopoly power by a country improves its

welfare. In this instance, the smuggler's exercise of his monopoly

power is tantamount (on our assumptions) to the country's adopting

an optimum tariff policy along the smuggling transformation curve;

hence it clearly yields a superior welfare level than if smuggling

were competitive.

II. EXOGENOUSLY SPECIFIED OBJECTIVES: TARGET INCREASE

IN IMPORTABLE PRODUCTION

The preceding analysis is essentially of interest where the

economist thinks either that the tariff policy is misconceived or that

it is a historical accident. In either case, the economist is likely to

argue -and indeed such arguments are frequently asserted in prac-

tice -that smuggling must be welfare-improving, a notion that

we have just demonstrated to be unsustainable as a general propo-

sition.

But suppose now that the tariff has been imposed to achieve

some definite end. Assume that the government wishes to achieve a

prespecified degree of protection for the import-competing industry.

We then have the following proposition:

To attain a feasible target increase in domestic production of

This content downloaded from

206.84.141.40 on Wed, 23 Aug 2023 19:28:06 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

A THEORETICAL ANALYSIS OF SMUGGLING 185

the importable good, a tariff with no smuggling is su

tariff with smuggling.

This proposition is illustrated in Figure IX. With the

tion point fixed by the target specification at P8(Pt), it

U, < Ut. Again, the rationale of this result can be readi

by noting that the fixing of the production point makes

tion distortion identical between the smuggling and the

gling situations, whereas the terms of trade under smug

ferior to those under legal trade. Consumption is again a

distorted prices (at Ct and C8 under the nonsmuggling an

gling situations, respectively). Hence smuggling must n

worsen welfare.

This result is of interest not merely because it reinforces our

critique of the customarily complacent view of smuggling, but also

because it would seem to us to provide yet another argument in sup-

port of the view that, for a production noneconomic objective, a

Y-EXP

A f

Ut~~~~U

0 B X- IMP

FIGURE IX

Smuggling at Predetermined Production Point

Note that the production of X, the importable good, cannot fall below

Ps=Pt. A suitable tariff, in the absence of smuggling, will take welfare to

Ut. A higher tariff, in the presence of smuggling (at transformation curve

PXCsS), would (necessarily) produce lower welfare at Us . The same result

could be illustrated for the case where smuggling does not eliminate legal

trade, as also for monopolistic smuggling.

This content downloaded from

206.84.141.40 on Wed, 23 Aug 2023 19:28:06 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

186 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

production tax cum subsidy policy is superior to a tariff policy.'

In the presence of smuggling, the tariff rate needed to encourage

domestic import-competing production is clearly greater than if

smuggling is not present, and this conclusion is clearly of consider-

able significance to countries such as Afghanistan and Indonesia,

where smuggling assumes significant dimensions.

III. OVERINVOICING AND UNDERINVOICING OF TRANSACTIONS

Our analysis of smuggling can also be readily extended to

quasi-smuggling phenomena, such as the overinvoicing and under-

invoicing of transactions on legal trade. We demonstrate how this

can be done for the case where the presence of a tariff duty leads

to underinvoicing of imports.

We should distinguish between two possibilities: (1) where

the underinvoicing of imports amounts merely to a de facto reduc-

tion in the tariff, so that the smuggling situation is equivalent to a

lowering of the tariff; and (2) where the resulting gain to the

importer has to be shared, in some degree, with the exporter who

collaborates in the faking of the invoices, in which case the effec-

tive c.i.f. price of importation to the importing country rises, en-

tailing a terms of trade loss.

Clearly, the latter case is equivalent to our analysis of smug-

gling, and therefore no modification in our conclusions is necessary.

However, in the former case, our conclusions get critically affected.

For, with underinvoicing amounting only to a lower tariff, it follows

that it must necessarily be superior to a non-underinvoicing situ-

ation, and for the case where a target-specified degree of domestic

production of the importable must be achieved, it clearly makes no

difference now whether there is faking of invoices or not; with fak-

ing, the tariff will just have to be set higher, and the faking-inclu-

sive real situation will then be identical with that which would have

obtained without faking but with a lower tariff.3

1. See W. M. Corden, "Tariffs, Subsidies, and the Terms of Trade,"

Economica, XXIV (1957), 235-42, and J. Bhagwati and T. N. Srinivasan,

"Optimal Intervention to Achieve Non-Economic Objectives," Review of

Economic Studies, XXXVI (1969), 27-38.

2. For earlier analyses of such phenomena, seeking different answers, see

Bhagwati, "Fiscal Policies, the Faking of Foreign Trade Declarations and the

Balance of Payments," Trade, Tariffs, and Growth (Cambridge: M.I.T. Press,

1969), pp. 266-94; Bhagwati and Padma Desai, India: Planning for Industrial-

ization (London: Oxford University Press, 1970); and G. Winston, "Overin-

voicing, Underutilization and Distorted Industrial Growth," Pakistan Develop-

ment Review, X (1970), 405-21.

3. As with smuggling, however, the degree of protection sought may be

unattainable in the presence of faking of invoices.

This content downloaded from

206.84.141.40 on Wed, 23 Aug 2023 19:28:06 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

A THEORETICAL ANALYSIS OF SMUGGLING 187

IV. CONCLUSIONS

We have thus managed to incorporate successfully the phe-

nomena of smuggling and faked invoicing into the welfare analysis

of tariffs. Our analysis is clearly generalizable, and in a sequel

to this paper we propose to extend our analysis into two major

areas: (1) the welfare analysis of domestic taxation, and (2) other

propositions in the theory of trade and welfare.4

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY

4. In particular, our analysis must be extended to a multiple-good model,

while the present analysis has explored only the two-good model throughout.

Further, we have dealt in the present paper only with the smuggling of goods

rather than of "bads" (such as heroin) or of assets (such as gold), whose

analysis must be conducted in the framework of differently constructed models.

Finally, we may note explicitly that we (correctly, in our view) conceive of

smuggling as necessarily taking place in the presence of governmental attempts

at enforcing the tariff. (Norman Mintz has pointed out to us that if we were

to postulate instead that the government does not do so, the smuggling equilib-

rium would be identical with the free-trade equilibrium: the real cost of smug-

gling trade would be no different from that of legal trade in this case because

the smugglers would be merely walking past the customs officers, choosing not

to pay the tariff and not being penalized for doing so! This situation would

be both nonsensical and unrealistic; we have therefore assumed that smug-

gling necessarily takes place in the context of enforcement.) As with tradi-

tional analysis, however, where the cost of operating the tariff is not explicitly

taken into account by, say, a shrunk-in production possibility curve, we have

simply ignored this aspect of the tariff-enforcement costs.

This content downloaded from

206.84.141.40 on Wed, 23 Aug 2023 19:28:06 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Master'S Thesis: "International Trade: Cost and Efficiency of Selected Payment Instruments"Document97 pagesMaster'S Thesis: "International Trade: Cost and Efficiency of Selected Payment Instruments"pasirwaktuNo ratings yet

- 1.3 International Economics: 2. Explain The Theory of Customs Union On Its Relevance To Developing CountriesDocument14 pages1.3 International Economics: 2. Explain The Theory of Customs Union On Its Relevance To Developing CountriesRajni KumariNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Eko InterDocument11 pagesJurnal Eko InterMuhammadJeffreyNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes On International Trade and Imperfect CompetitionDocument55 pagesLecture Notes On International Trade and Imperfect CompetitionVimal SinghNo ratings yet

- TRADEBOOKDocument174 pagesTRADEBOOKMwawiNo ratings yet

- Differences between inter-regional and international tradeDocument30 pagesDifferences between inter-regional and international tradeSuzi GamingNo ratings yet

- Terms of TradeDocument14 pagesTerms of TradeNaman Mishra100% (2)

- Research in Global Strategic ManagementDocument27 pagesResearch in Global Strategic ManagementALexandra de RobillardNo ratings yet

- 1 International Trade and Trade Theory: See, For Instance, Faini (2005)Document22 pages1 International Trade and Trade Theory: See, For Instance, Faini (2005)Nirjhar DuttaNo ratings yet

- Module 2: Classical International Trade Theories 2.1 Learning ObjectivesDocument11 pagesModule 2: Classical International Trade Theories 2.1 Learning ObjectivesPrince CalicaNo ratings yet

- International Economics ExplainedDocument16 pagesInternational Economics ExplainedBernard OkpeNo ratings yet

- International Economics Is Concerned With The EffectsDocument44 pagesInternational Economics Is Concerned With The EffectsDarshana UdaraNo ratings yet

- Free Trade Unemployment and Economic PolDocument20 pagesFree Trade Unemployment and Economic Polpablo merinoNo ratings yet

- Trade Law-AssignmentDocument11 pagesTrade Law-AssignmentashishNo ratings yet

- International Trade Theories OverviewDocument20 pagesInternational Trade Theories Overviewindraa 04No ratings yet

- Static and Dynamic Comparative Advantage MultiDocument8 pagesStatic and Dynamic Comparative Advantage MultiSusiraniNo ratings yet

- Research Papers On International Trade LawDocument10 pagesResearch Papers On International Trade Lawefdkhd4e100% (1)

- The Impact of Trade Openness On Economic Growth: Evidence in Developing CountriesDocument32 pagesThe Impact of Trade Openness On Economic Growth: Evidence in Developing CountriesLim JiungNo ratings yet

- CROATIADocument15 pagesCROATIAMutharimeBin-MwitoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 International TradeDocument14 pagesChapter 6 International Traderfbn9fvc8cNo ratings yet

- International TradeDocument21 pagesInternational TradeAngelikha LealNo ratings yet

- Anderson and Wincoop (2004) Trade CostsDocument62 pagesAnderson and Wincoop (2004) Trade CostsRoberto MirandaNo ratings yet

- Prebisch Singer Hypothesis PDFDocument5 pagesPrebisch Singer Hypothesis PDFsandyharwellevansville100% (2)

- 3.1 deepak seriesDocument61 pages3.1 deepak seriesmansoorshaik030No ratings yet

- The Pure International Trade Theory: Supply: February 2018Document28 pagesThe Pure International Trade Theory: Supply: February 2018Swastik GroverNo ratings yet

- The Quarterly Journal of Economics 2008 Helpman 441 87Document47 pagesThe Quarterly Journal of Economics 2008 Helpman 441 87Ricardo CaffeNo ratings yet

- Estimation and Machine Learning Prediction of Imports of Goods in European Countries in The Period 2010-2019Document18 pagesEstimation and Machine Learning Prediction of Imports of Goods in European Countries in The Period 2010-2019AJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Mercantilism: Definition of 'Appreciation'Document23 pagesMercantilism: Definition of 'Appreciation'imax009No ratings yet

- 56 1palan PDFDocument27 pages56 1palan PDFavijitfNo ratings yet

- Information Effects On The Bid-Ask Spread: Thomas E. Copeland Dan GalaiDocument13 pagesInformation Effects On The Bid-Ask Spread: Thomas E. Copeland Dan GalaiTahir SajjadNo ratings yet

- International Bussiness Environment N14B44Document18 pagesInternational Bussiness Environment N14B44BenjaminTehNo ratings yet

- Trade Theory and Trade Facts : Raphael BergoeingDocument45 pagesTrade Theory and Trade Facts : Raphael BergoeingRavi ChandNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document13 pagesChapter 4Ermias AtalayNo ratings yet

- Findlay (1988)Document52 pagesFindlay (1988)Roberta Faccin FerreiraNo ratings yet

- International Trade in The Presence of Product Differentiation, Economies of Scale and Monopolistic Competition A Chamberlin-Heckscher-Ohlin ApproachDocument36 pagesInternational Trade in The Presence of Product Differentiation, Economies of Scale and Monopolistic Competition A Chamberlin-Heckscher-Ohlin ApproachDavid CernaNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 International Trade TheoryDocument10 pagesUnit 3 International Trade TheoryleyonrajNo ratings yet

- Exchange Rates MovementsDocument63 pagesExchange Rates MovementsPrerna GoelNo ratings yet

- Unit 2Document13 pagesUnit 2Aditya SinghNo ratings yet

- Monopoly power and export drawback schemesDocument29 pagesMonopoly power and export drawback schemesPilar RiveraNo ratings yet

- Gravity Equations and Economic FrictionsDocument49 pagesGravity Equations and Economic FrictionsTito HerreraNo ratings yet

- International Trade in The Presence of Product Differentiation, Economies of Scale and Monopolistic Competition A Chamberlin-Heckscher-Ohlin ApproachDocument36 pagesInternational Trade in The Presence of Product Differentiation, Economies of Scale and Monopolistic Competition A Chamberlin-Heckscher-Ohlin ApproachAlade Azeez KolaNo ratings yet

- Labour Law TUTRIALDocument9 pagesLabour Law TUTRIALsadhvi singhNo ratings yet

- International Trade Theory and Development Strategy HandoutsDocument3 pagesInternational Trade Theory and Development Strategy HandoutsHazell D100% (2)

- Lesson 7Document9 pagesLesson 7Pragadesh Hari. SNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 (IBT)Document5 pagesChapter 2 (IBT)Nicolle CurammengNo ratings yet

- Aligarh Muslim University Mallapuram Center Kerala: Mid Term of International Trade Law TopicDocument12 pagesAligarh Muslim University Mallapuram Center Kerala: Mid Term of International Trade Law Topicsadhvi singhNo ratings yet

- MN 55455, USA: of MinnesotaDocument15 pagesMN 55455, USA: of MinnesotaJorge Eduardo Ortega PalaciosNo ratings yet

- Literature SurveyDocument36 pagesLiterature SurveyParameswaran T.N.No ratings yet

- Free Trade and Protectionism in A French Region at The End of The Nineteenth CenturyDocument17 pagesFree Trade and Protectionism in A French Region at The End of The Nineteenth CenturyShane CharltonNo ratings yet

- The Wto and Trade Economics: Theory and PolicyDocument26 pagesThe Wto and Trade Economics: Theory and Policy03fl22bcl033No ratings yet

- Final Draft - Economics ProjectDocument18 pagesFinal Draft - Economics ProjectShra19No ratings yet

- Economic Consequences of Export InstabilityDocument16 pagesEconomic Consequences of Export InstabilityNidhi BahotNo ratings yet

- International Trade Theories and Guyana's ExportsDocument20 pagesInternational Trade Theories and Guyana's ExportsJenneil CarmichaelNo ratings yet

- Help Man 2008Document47 pagesHelp Man 2008Ricardo CaffeNo ratings yet

- International Trade 1Document20 pagesInternational Trade 1AR RahoojoNo ratings yet

- On The Role of Financial Frictions and The Saving Rate During Trade LiberalizationsDocument14 pagesOn The Role of Financial Frictions and The Saving Rate During Trade LiberalizationsNamitBhasinNo ratings yet

- Rntraduelion: University Tokyo, Bmkyo-Ku, Tokyo, J&NMDocument17 pagesRntraduelion: University Tokyo, Bmkyo-Ku, Tokyo, J&NMReynaldo DurandNo ratings yet

- Thirlwall Model 50 Years ReviewDocument45 pagesThirlwall Model 50 Years ReviewfofikoNo ratings yet

- Bycycle Smuggling MPRA - Paper - 116553Document56 pagesBycycle Smuggling MPRA - Paper - 116553Abbas KhanNo ratings yet

- Trade in Goods and Services OvernightDocument18 pagesTrade in Goods and Services OvernightAbbas KhanNo ratings yet

- A Critical Analysis of The Financing Problems Faced by Small and Medium EnterprisesDocument1 pageA Critical Analysis of The Financing Problems Faced by Small and Medium EnterprisesAbbas KhanNo ratings yet

- Urdu Theses of M.A Islamic Studies & Equivalent Degree Programs on Study of Religions from Pakistan:A Detailed Index & Statistical Analysis = نﺎﯾدا ﻌﻟﺎﻄﻣ مﻮﻠﻋ ا ﻢﯾا ﮟﯿﻣ نﺎﺘﺴﮐﺎﭘﺮﭘ..Document66 pagesUrdu Theses of M.A Islamic Studies & Equivalent Degree Programs on Study of Religions from Pakistan:A Detailed Index & Statistical Analysis = نﺎﯾدا ﻌﻟﺎﻄﻣ مﻮﻠﻋ ا ﻢﯾا ﮟﯿﻣ نﺎﺘﺴﮐﺎﭘﺮﭘ..sara orakzaiiNo ratings yet

- Wps PrenhallDocument1 pageWps PrenhallsjchobheNo ratings yet

- Friends discuss comedy and plan to see a comic showDocument2 pagesFriends discuss comedy and plan to see a comic showПолина НовикNo ratings yet

- Rdbms (Unit 2)Document9 pagesRdbms (Unit 2)hari karanNo ratings yet

- Grammar Marwa 22Document5 pagesGrammar Marwa 22YAGOUB MUSANo ratings yet

- D20 Modern - Evil Dead PDFDocument39 pagesD20 Modern - Evil Dead PDFLester Cooper100% (1)

- Ambahan Poetry of The HanuooDocument4 pagesAmbahan Poetry of The HanuooJayrold Balageo MadarangNo ratings yet

- Amazon - in - Order 402-9638723-6823558 PDFDocument1 pageAmazon - in - Order 402-9638723-6823558 PDFanurag kumarNo ratings yet

- Semi Anual SM Semana 15Document64 pagesSemi Anual SM Semana 15Leslie Caysahuana de la cruzNo ratings yet

- Activate 3 Physics Chapter2 AnswersDocument8 pagesActivate 3 Physics Chapter2 AnswersJohn LebizNo ratings yet

- ?PMA 138,39,40,41LC Past Initials-1Document53 pages?PMA 138,39,40,41LC Past Initials-1Saqlain Ali Shah100% (1)

- On 1 October Bland LTD Opened A Plant For MakingDocument2 pagesOn 1 October Bland LTD Opened A Plant For MakingCharlotteNo ratings yet

- FT817 DIY Data Modes Interface v2.0Document7 pagesFT817 DIY Data Modes Interface v2.0limazulusNo ratings yet

- History of GB Week12 PresentationDocument9 pagesHistory of GB Week12 PresentationIzabella MigléczNo ratings yet

- Apa, Muzica Si Ganduri: Masaru Emoto Was Born in Yokohama in July 1943. He Is A Graduate of The Yokohama MunicipalDocument4 pagesApa, Muzica Si Ganduri: Masaru Emoto Was Born in Yokohama in July 1943. He Is A Graduate of The Yokohama MunicipalHarlea StefanNo ratings yet

- Assigment 2Document3 pagesAssigment 2Aitor AguadoNo ratings yet

- ĐỀ THI GIỮA KÌ 2 - E9 (TẤN)Document4 pagesĐỀ THI GIỮA KÌ 2 - E9 (TẤN)xyencoconutNo ratings yet

- Cultural Etiquette and Business Practices in FranceDocument15 pagesCultural Etiquette and Business Practices in FranceVicky GuptaNo ratings yet

- FF6GABAYDocument520 pagesFF6GABAYaringkinkingNo ratings yet

- UoGx ECEg4155 Chapter 7 8Document45 pagesUoGx ECEg4155 Chapter 7 8Abdi ExplainsNo ratings yet

- OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY REGULATIONSDocument126 pagesOCCUPATIONAL SAFETY REGULATIONSKarthikeyan Sankarrajan100% (3)

- Dataoverwritesecurity Unit Type C Dataoverwritesecurity Unit Type DDocument12 pagesDataoverwritesecurity Unit Type C Dataoverwritesecurity Unit Type DnamNo ratings yet

- Sinha-Dhanalakshmi2019 Article EvolutionOfRecommenderSystemOv PDFDocument20 pagesSinha-Dhanalakshmi2019 Article EvolutionOfRecommenderSystemOv PDFRui MatosNo ratings yet

- ICT in Education ComponentsDocument2 pagesICT in Education ComponentsLeah RualesNo ratings yet

- Lasallian Core ValuesDocument1 pageLasallian Core ValuesLindaRidzuanNo ratings yet

- Cause and Effects of Social MediaDocument54 pagesCause and Effects of Social MediaAidan Leonard SeminianoNo ratings yet

- Case Study - FGD PDFDocument9 pagesCase Study - FGD PDFLuthfanTogarNo ratings yet

- Poultry Fool & FinalDocument42 pagesPoultry Fool & Finalaashikjayswal8No ratings yet

- Client Hunting HandbookDocument105 pagesClient Hunting Handbookc__brown_3No ratings yet

- Book Review in The Belly of The RiverDocument4 pagesBook Review in The Belly of The RiverJulian BaaNo ratings yet

- National Scholars Program 2005 Annual Report: A Growing Tradition of ExcellenceDocument24 pagesNational Scholars Program 2005 Annual Report: A Growing Tradition of ExcellencejamwilljamwillNo ratings yet

- University of Berkshire Hathaway: 30 Years of Lessons Learned from Warren Buffett & Charlie Munger at the Annual Shareholders MeetingFrom EverandUniversity of Berkshire Hathaway: 30 Years of Lessons Learned from Warren Buffett & Charlie Munger at the Annual Shareholders MeetingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (97)

- The War Below: Lithium, Copper, and the Global Battle to Power Our LivesFrom EverandThe War Below: Lithium, Copper, and the Global Battle to Power Our LivesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- A History of the United States in Five Crashes: Stock Market Meltdowns That Defined a NationFrom EverandA History of the United States in Five Crashes: Stock Market Meltdowns That Defined a NationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (11)

- The Infinite Machine: How an Army of Crypto-Hackers Is Building the Next Internet with EthereumFrom EverandThe Infinite Machine: How an Army of Crypto-Hackers Is Building the Next Internet with EthereumRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (12)

- Second Class: How the Elites Betrayed America's Working Men and WomenFrom EverandSecond Class: How the Elites Betrayed America's Working Men and WomenNo ratings yet

- Vulture Capitalism: Corporate Crimes, Backdoor Bailouts, and the Death of FreedomFrom EverandVulture Capitalism: Corporate Crimes, Backdoor Bailouts, and the Death of FreedomNo ratings yet

- Chip War: The Quest to Dominate the World's Most Critical TechnologyFrom EverandChip War: The Quest to Dominate the World's Most Critical TechnologyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (227)

- Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic EventsFrom EverandNarrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic EventsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (94)

- The Trillion-Dollar Conspiracy: How the New World Order, Man-Made Diseases, and Zombie Banks Are Destroying AmericaFrom EverandThe Trillion-Dollar Conspiracy: How the New World Order, Man-Made Diseases, and Zombie Banks Are Destroying AmericaNo ratings yet

- The Technology Trap: Capital, Labor, and Power in the Age of AutomationFrom EverandThe Technology Trap: Capital, Labor, and Power in the Age of AutomationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (46)

- Kleptopia: How Dirty Money Is Conquering the WorldFrom EverandKleptopia: How Dirty Money Is Conquering the WorldRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (25)

- Look Again: The Power of Noticing What Was Always ThereFrom EverandLook Again: The Power of Noticing What Was Always ThereRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Nudge: The Final Edition: Improving Decisions About Money, Health, And The EnvironmentFrom EverandNudge: The Final Edition: Improving Decisions About Money, Health, And The EnvironmentRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (92)

- The Genius of Israel: The Surprising Resilience of a Divided Nation in a Turbulent WorldFrom EverandThe Genius of Israel: The Surprising Resilience of a Divided Nation in a Turbulent WorldRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Principles for Dealing with the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed or FailFrom EverandPrinciples for Dealing with the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed or FailRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (237)

- Economics 101: From Consumer Behavior to Competitive Markets—Everything You Need to Know About EconomicsFrom EverandEconomics 101: From Consumer Behavior to Competitive Markets—Everything You Need to Know About EconomicsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The ClimateFrom EverandThis Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The ClimateRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (349)

- The Finance Curse: How Global Finance Is Making Us All PoorerFrom EverandThe Finance Curse: How Global Finance Is Making Us All PoorerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (18)

- The Myth of the Rational Market: A History of Risk, Reward, and Delusion on Wall StreetFrom EverandThe Myth of the Rational Market: A History of Risk, Reward, and Delusion on Wall StreetNo ratings yet

- Financial Literacy for All: Disrupting Struggle, Advancing Financial Freedom, and Building a New American Middle ClassFrom EverandFinancial Literacy for All: Disrupting Struggle, Advancing Financial Freedom, and Building a New American Middle ClassNo ratings yet

- The Lords of Easy Money: How the Federal Reserve Broke the American EconomyFrom EverandThe Lords of Easy Money: How the Federal Reserve Broke the American EconomyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (69)

- Kaizen: The Ultimate Guide to Mastering Continuous Improvement And Transforming Your Life With Self DisciplineFrom EverandKaizen: The Ultimate Guide to Mastering Continuous Improvement And Transforming Your Life With Self DisciplineRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (36)