Professional Documents

Culture Documents

WEsterlund & LAgerberg (2008) Mother Caracteristics and Expressive Vocabulary at 18 Months

Uploaded by

Zareth GarroOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

WEsterlund & LAgerberg (2008) Mother Caracteristics and Expressive Vocabulary at 18 Months

Uploaded by

Zareth GarroCopyright:

Available Formats

Original Article doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2007.00801.

Expressive vocabulary in 18-month-old children

in relation to demographic factors, mother and

child characteristics, communication style and

shared reading

M. Westerlund*† and D. Lagerberg*

*Department of Women’s and Children’s Health, Section for Paediatrics, Uppsala University, Children’s Hospital, and

†Central Unit for Child Health Care, Children’s Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden

Accepted for publication 2 September 2007

Abstract

Background Previous research has elucidated the associations between children’s language

development and reading habits, and maternal education, communication style, gender and birth

order. Research including maternal age and child temperament is more scarce. We studied the

associations of all these factors with children’s expressive vocabulary and reading habits. We also

analysed the relationships of reading with expressive vocabulary, and effect sizes associated with

frequent reading.

Methods Questionnaires were completed by mothers of 1091 children aged 17–19 months

visiting the Swedish Child Health Services. Expressive vocabulary was assessed by the Swedish

Keywords

Communication Screening at 18 months, a screening version of McArthur-Bates Communicative

communication, Development Inventories. Mother’s perception of ability to communicate was measured by a scale

expressive vocabulary,

constructed ad hoc from the International Child Development Programmes, a parent education

maternal report, reading,

screening curriculum. Bates’ ‘difficultness’ scale was used to assess temperament.

Results Good communication, low maternal age, female gender and frequent reading were

Correspondence: significantly associated with expressive vocabulary. High maternal education, good communication,

Monica Westerlund,

Assistant Professor,

higher maternal age, female gender and being a first-born child were significantly associated with

Central unit for child frequent reading. Reading at least 6 times/week added more than 0.3 SD in vocabulary regardless

health care, Uppsala

of gender and communication.

county, Children’s

Hospital, SE-751 85 Conclusions The findings support the importance of reading and communication quality to early

Uppsala, Sweden language development. Knowledge of the relationship between children’s vocabulary and book

E-mail:

monica.westerlund@

reading in a context of joint attention is both theoretically and practically valuable to speech and

akademiska.se language pathologists, pre-school teachers, child health workers and other professionals.

tering of a country’s majority language is a great psychosocial

Introduction

disadvantage not solely for children growing up with a minority

Our present society makes heavy demands on the linguistic language. Young children are strongly ‘programmed’ for com-

ability of the population, both native and immigrant. Poor mas- munication. It is important to make the most of this and of the

© 2008 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 257

258 M. Westerlund and D. Lagerberg

plasticity of the young human brain indicating a high learning First-born children are usually verbally ahead of later-born

potential in the early years of life. children – at least in the early years (Fenson et al. 1994;

Hoff-Ginsberg 1998; Berglund et al. 2005). The association is

explained as being mediated by the mothers’ way of talking to

Some maternal factors related to child language their children. Mothers of first-borns have been found to make

more explicit attempts at eliciting language from their toddlers

Many studies have elucidated the strong link between socio-

than mothers of later-born children (Jones & Adamson 1987).

economic status (SES) and children’s verbal abilities (e.g. Born-

Few studies have addressed specific associations between

stein et al. 1998; Hoff-Ginsberg 1998; Locke et al. 2002). Core

language development and children’s temperament. However,

factors often applied in definitions of SES are education, occu-

according to Dixon and Smith (2000), mothers’ ratings of their

pation and income. As for early language development, the most

toddler’s attention were related to language production. This

influential SES component seems to be education, particularly

was later verified in a study by Karrass and colleagues (2002).

maternal education, as the mother tends to be intensively

involved in daily interactions offering rich opportunities for

conversation. Some factors related to book reading with young children

The importance of SES appears to be mediated by commu-

As pointed out by Scarborough and Dobrich (1994), children

nication style (Bornstein et al. 1998; Landry et al. 2002; Hoff &

from lower-class families are usually read to less often than

Tian 2005), e.g. the amount and complexity of verbal commu-

children from higher-SES families (Bornstein et al. 1998; Hoff-

nication available to the child (Hart & Risley 1995). Inviting the

Ginsberg 1998; Locke et al. 2002). However, Roberts and col-

child to take part in conversations, describing and explaining

leagues (2005) maintained that mothers’ education was only

what is around are activities likely to expand concept formation

mildly correlated with frequency of shared reading, and Kuo

and linguistic capacity (Manolson 1992; Girolametto et al.

and colleagues (2004) found indications of low reading fre-

1999). Low-SES mothers have been found to approach their

quencies even in better-off families.

children with many directives not linked to the child’s current

Communication style is probably related to reading prefer-

interest, as well as with requests calling for an expected response

ences in families of young children. Shared reading may be a

(Hoff-Ginsberg 1991). According to Landry and colleagues

marker of a generally stimulating environment (Karrass et al.

(2002), they may also use so-called ‘empty language’ (‘this’ and

2003). If so, parents most disposed to attend to their children’s

‘that’ instead of more specific language).

verbal and non-verbal signals in settings other than reading

Maternal age can be hypothesized to influence child’s lan-

would also be the ones most inclined to read frequently with

guage directly, perhaps because older mothers may be more

them.

patient and talk more with their children, or because, con-

As far as is known by the authors, no study has explored a

versely, they are more tired than younger mothers, thus talking

possible association between mothers’ age and shared reading.

less with them. Pan and colleagues (2004) found no significant

However, an association might be hypothesized between paren-

associations of maternal age with child language at age 2.

tal views of the importance of linguistic stimulation and mater-

However, this study involved low-income families only, which

nal age.

may have restricted the potential scope for variations by mater-

Provided that girls are linguistically ahead of boys, and

nal age.

parents modify their reading habits to the child’s verbal ability,

then one could expect mothers to read more with their daugh-

ters. However, according to some studies, reading with young

Some child factors related to language

children does not differ between the genders (High et al. 1999;

Girls’ language development is usually ahead of boys’ (e.g. Roberts et al. 2005).

Bornstein & Haynes 1998; Locke et al. 2002). A slight female As to birth order, Kuo and colleagues (2004) found differing

advantage explaining between 1% and 3% of the variance was odds for daily reading depending on whether the child was an

reported from two large-scale studies of children aged only child or not. Children with siblings were read to more

8–30 months (Fenson et al. 1994; Galsworthy et al. 2000). A seldom.

Swedish study of more than 1000 children showed significant The relation between child temperament (attention) and

differences in favour of girls’ verbal comprehension and pro- book reading has been studied by Karrass and colleagues (2003)

duction (Berglund et al. 2005). in middle-class families with 8-month-old children. No associa-

© 2008 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child: care, health and development, 34, 2, 257–266

Expressive vocabulary in 18-month-old children 259

tion was found between mothers’ book reading and the child’s 2003–March 2004) who visited their Child Health Centres

temperament, whereas fathers read more with their fussy chil- (CHC), situated in six different counties of Sweden, for an

dren than with their quiet ones. 18-month check-up (Sundelin et al. 2005).

Of 2179 children invited to participate, the mothers of 1541

Shared reading and language development (70.7%) completed the questionnaire. Twins (n = 48) and chil-

dren outside the age range of 18 ⫾ 1 month were excluded. The

Already in the late eighties, Whitehurst and colleagues (1988) study population thus consisted of 1091 children (17 months

showed book reading to be associated with an increased n = 66, 18 months n = 625 and 19 months n = 400). There

vocabulary in children. Since then, several researchers have were 546 boys and 545 girls, of whom 45.9% were first-born

highlighted the importance of shared reading with young children. As participation in Swedish child health services is

children (Golova et al. 1999; High et al. 2000; Whitehurst & almost 100% (Magnusson 1997), the study can be considered

Lonigan 2001). In the light of growing evidence that parent– population-based.

child reading activities represent a particularly rich source of Swedish mothers dominated the material (84%). All mothers,

verbal interactions (e.g. Hoff-Ginsberg 1991), several book- irrespectively of national origin, were included.

giving projects have been implemented (for a review, see Klass The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committees

et al. 2003), some of which have been subject of evaluation of the universities involved (Dnr Ups 01–342).

studies. High and colleagues (2000) found significant increases

in both receptive and expressive language for children of

18 months and older, whose parents had received children’s Procedure and questionnaire

books, educational materials and advice about sharing books.

When visiting the CHCs for their children’s 18-month check-

Hoff-Ginsberg (1991) studied mothers and their 18–29-

up, the mothers were invited to participate. Upon acceptance,

month-old toddlers in four settings (mealtime, dressing,

they were given a questionnaire and a post-free return enve-

reading and toy play). Differences between the less contingent

lope. Help by interpreters was offered to non-Swedish-

speech among lower-class mothers compared with that of

speaking mothers. The questionnaire included, among others,

middle-class mothers were considerably minimized in the

questions about demographic characteristics, reading with the

reading situation. These findings stress the importance of

child and the mother’s perception of the child’s temperament.

reading as a means to language acquisition.

The mothers were also asked to rate the quality of their

Even if communication and reading habits work very much

communication with the child as well as the child’s current

in the same direction, it may nevertheless be the case that both

vocabulary.

make independent contributions to children’s language devel-

opment. This matter, among others, will be dealt with in the

following.

Description of variables

Methods • Maternal education (four categories, ordinal scale): primary

school or lower, 2 years of secondary school, 3–4 years of sec-

Aims of the study ondary school and university/college.

The present study examined cross-sectional associations with • Mother’s communication: the scale was constructed ad hoc on

expressive vocabulary and with reading habits of the following the basis of themes from the International Child Develop-

factors: maternal education (as a marker of SES), communi- ment Programmes, a parent education curriculum (Hundeide

cation style, maternal age, child gender, birth order and 1996). Items:

‘difficultness’ (as an aspect of temperament). The association of To what extent do you think you are good enough to:

reading habits with children’s language development was also be aware of the child’s needs and wishes; communicate with

explored. the child about things that catch his/her interest; encourage

the child; help the child to give attention to things and events

around; describe to the child what you experience together;

Participants

explain to the child what you experience together? There were

This paper drew on data from an extensive study of two cohorts five scores: 1 (very little), 2 (rather little), 3 (moderately), 4

of children (born September 2000–August 2001 and April (rather much) and 5 (very much). Total score was calculated

© 2008 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child: care, health and development, 34, 2, 257–266

260 M. Westerlund and D. Lagerberg

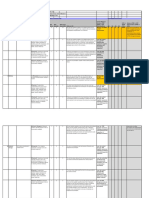

as the means of all items. Scale dimensionality was good Table 1. Means (M), standard deviations (SD) and ranges for

communication, child difficultness and expressive vocabulary

(Cronbach’s alpha: 0.92). Dichotomized into high (>mean for

whole sample) and low (ⱕmean) for bivariate analyses and Variable n* M SD Range

calculations of effect sizes; continuous variable in multiple Communication† 1077 4.15 0.64 1.00–5.00

regression analyses. Difficultness‡ 1089 3.55 0.83 1.00–6.33

Expressive vocabulary 1067 29.4 20.5 0–87

• Maternal age (year of birth) when completing the question-

Total n = 1091.

naire (five categories for univariate and bivariate analyses;

*Varying ns are due to missing values.

continuous variable in multiple regression analyses). †High scores are favourable.

• The child’s gender and birth order dichotomized into male/ ‡Low scores are favourable.

female and first-born or not.

• The child’s difficultness according to Bates (Bates et al. 1979): control for independent variables, multiple linear regression

mother’s mean score on nine items ranging from 1 (low dif- analyses with standardized beta weights were performed. Effect

ficultness) to 7 (high difficultness). The mother is encouraged sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d with weighted SDs. Effect

to compare her child with an imagined ‘average’ child. Items sizes are intended to express clinical relevance, with 1 corre-

deal with easiness–difficulty to calm the child, irritability, sponding to one standard deviation. An effect of 0.8 is generally

crying, temper, etc. Scale dimensionality was good (Cron- considered large, an effect size of 0.5 as medium and a size of 0.2

bach’s alpha: 0.83). Dichotomized into low (<mean for whole as small (Kirk 1996). Analyses were performed with the SAS

sample) and high (ⱖmean) for bivariate analyses; continuous package for personal computers (SAS Institute Inc. 1987).

variable in multiple regression analyses. P-values below 0.05 were accepted as significant.

• Shared book reading (five categories, ordinal scale): How many

times, per week, do you or someone else in the family look in

Results

a book together with your child (10 or more times, 6–9 times,

3–5 times, 1–2 times, or never)? Dichotomized into <6 times/ The accuracy of the verbal checklist method was supported by

week and ⱖ6 times/week for some bivariate analyses (Table 4) the findings, showing an almost perfect gradient by age. Thus

and for calculations of effect sizes. the mean number and maximum of spoken words were 25.2

• The child’s expressive vocabulary (continuous variable): and 76, respectively, in the youngest children (17 months), 28.3

Number of spoken words marked by the mother on a check- and 84 in the 18-month olds, and 31.7 and 87 in the oldest

list of 90 common words. This instrument, SCS18, is a screen- group (19 months).

ing version of the Swedish Communicative Development Means, SDs and frequencies are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Inventories (Eriksson & Berglund 1999; Berglund & Eriksson Mothers were quite satisfied with their communication with

2000), which in turn is a Swedish adaptation of the the child: the average score exceeded 4 corresponding to ‘rather

MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories much’. Child difficultness lay in the middle of the scale corre-

(Fenson et al. 1993). The psychometric properties of the sponding to an ‘average’ child. The mean number of words

Swedish screening version (SCS18) have been analysed, expressed by the children was 29 out of the 90 words of the

showing high internal consistency, high test–retest reliability SCS18. As shown in Table 2, 105 mothers (9.6%) were low-

and strong associations with the corresponding scores from educated – at most, finished primary school – whereas more

the complete Swedish battery (for details and a verbatim than 2/5 had a college or university education. Frequent reading

English translation of the questionnaire, see Eriksson et al. (ⱖ6 times/week) was reported for 65.9% of the children,

2002). whereas 14.4% were read to more seldom (0–2 times/week).

About 15% of the mothers were below 25 or above 39 years of

age.

Statistical analyses and methods

Tables 3 and 4 show bivariate relationships between the inde-

When there were missing values in a particular variable, the pendent variables maternal education, communication, mater-

child in question was excluded from the analyses. n values thus nal age, child gender, child birth order and child difficultness,

varied and amounted to between 1039 and 1083 (out of totally and the dependent variables expressive vocabulary (Table 3)

1091). Differences between percentages were significance tested and shared reading (Table 4). In Table 3, shared reading has

with the c2 method, and differences between means with the been added among the independent variables, thus displaying

analysis of variance (anova) procedure and Student’s t-test. To its association with vocabulary.

© 2008 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child: care, health and development, 34, 2, 257–266

Expressive vocabulary in 18-month-old children 261

Table 2. Frequencies for maternal education, maternal age, child gender, was also a significant but weaker contribution by maternal age

child birth order and shared reading

(low, P = 0.0052). Maternal education, birth order and child

Independent variable n % difficultness did not contribute significantly to expressive

Maternal education vocabulary, controlling for other independent variables. The

Primary or less 105 9.6 significant association from the bivariate analysis with birth

Secondary: 2 years 188 17.2

Secondary: 3 or 4 years 313 28.7

order thus disappeared, and a significant association with

College or university 476 43.6 maternal age emerged when this variable was entered as a con-

Information missing 9 0.8 tinuous scale. Repeating the analysis for boys and girls sepa-

Maternal age

rately, the same variables yielded significant associations, except

18–24 84 7.7

25–29 255 23.4 for the association with maternal age in girls. The model

30–34 396 36.3 explained 9.65% of the variance among boys, and 5.44% of the

35–39 270 24.7

variance among girls (data not shown).

40–48 79 7.2

Information missing 7 0.6 The results of a multiple linear regression analysis using

Child gender shared reading as the dependent variable are shown in Table 6

Boys 546 50.0 with both genders pooled together.

Girls 545 50.0

Child birth order

The model explained 16.88% of the variance (d.f. = 6,

First-born 501 45.9 F = 36.88, P < 0.0001). The strongest association, controlling

Later-born 590 54.1 for other variables, appeared for communication: mothers

Shared reading

who perceived their communicative capacity to be good

10 or more times/week 464 42.5

6–9 times/week 255 23.4 tended to read more with their children. Children of highly

3–5 times/week 207 19.0 educated mothers and first-born children participated more

1–2 times/week 133 12.2

in shared reading. There was a positive significant association

Never 24 2.2

Information missing 8 0.7 between reading and maternal age as a continuous variable (all

Total 1091 100 P-values < 0.0001). Finally, the significant association with

gender (girls) remained after controlling for other indepen-

dent variables (P = 0.0006). Analysing boys and girls sepa-

There was no significant association between maternal edu- rately, the same independent variables as for the two genders

cation and child vocabulary (Table 3). On the other hand, there pooled together showed significant associations with reading.

was a steep and highly significant increase in reading frequency The model explained 17.01% of the variance among boys and

with rising maternal education (Table 4). Children whose 15.49% of the variance among girls (data not shown).

mothers felt they communicated well with them had a signifi-

cantly larger expressive vocabulary and participated signifi-

Effect sizes

cantly more in reading than other children. The same was true

for girls and first-born children as related to boys and later- In order to convey an idea of the potential ‘impact’ of reading on

borns respectively. There were no significant associations for expressive vocabulary, given variations in gender and perceived

either vocabulary or frequent reading with child difficultness. communication, effect sizes are presented in Table 7. Effect size

Frequent reading was strongly and significantly related to should be interpreted as the proportion of one SD added to

expressive vocabulary (Table 3). expressive vocabulary by frequent book reading, i.e. at least 6

times/week.

Boys whose mothers judged their communication as less

Multiple linear regression analyses

than good and who were not frequently read to reached a

Table 5 shows the results of a multiple linear regression analysis mean of 17.8 words, to be compared with 23.8 for comparable

with expressive vocabulary as the dependent variable. Both boys who were frequently read to, a difference of 0.35 SD. Girls

genders were pooled together. with a good communication had an expressive vocabulary

The model explained 12.91% of the variance (d.f. = 7, of 31.6 words if they participated less frequently in shared

F = 22.98, P < 0.0001). The most important factor was the reading, and 38.2 words if they were read to 6 times per week

child’s gender (girl), followed by shared reading (frequent) and or more (0.32 SD). In general, frequent reading was associated

perceived communication (good) (all P-values < 0.0001). There with a gain in expressive vocabulary of about 0.4 SD (an

© 2008 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child: care, health and development, 34, 2, 257–266

262 M. Westerlund and D. Lagerberg

Table 3. Expressive vocabulary by maternal

Dependent variable: expressive vocabulary

education, communication, maternal age,

Independent variable n Mean SD Range P child gender, child birth order, child

difficultness and shared reading.

Maternal education (d.f. = 3) 0.1628

Primary or less 103 26.8 21.8 0–80

Secondary: 2 years 185 29.8 20.9 0–86

Secondary: 3 or 4 years 306 31.4 20.4 0–84

College or university 465 28.6 20.0 0–87

Communication* <0.0001

Score >mean 555 32.2 20.5 0–87

Score ⱕmean 500 26.1 19.8 0–84

Maternal age (d.f. = 4) 0.1501

18–24 83 32.3 21.3 0–79

25–29 250 31.2 20.5 0–86

30–34 388 28.8 19.7 0–85

35–39 263 27.3 21.4 0–84

40–48 76 29.1 20.0 2–87

Child gender <0.0001

Boys 533 24.3 18.7 0–86

Girls 534 34.4 20.9 0–87

Child birth order 0.0021

First-born 493 31.4 20.8 0–86

Later-born 574 27.6 20.1 0–87

Child difficultness† 0.0934

Score <mean 495 30.5 20.9 0–87

Score ⱖmean 571 28.4 20.1 0–86

Shared reading (d.f. = 4) <0.0001

10 or more times/week 452 34.3 21.1 0–87

6–9 times/week 252 29.3 19.5 0–86

3–5 times/week 205 24.6 18.8 0–85

1–2 times/week 130 22.0 17.9 0–80

Never 22 14.0 14.4 0–64

Total 1067 29.4 20.5 0–87

Significance tests by analysis of variance and Student’s t-test. Observations with missing values excluded.

*High scores are favourable.

†Low scores are favourable.

almost medium effect size). The largest increases occurred for

Comments

boys with a good communication and for girls with a less than

good communication. In line with some earlier studies (Pan et al. 2004; Berglund

et al. 2005), but contrary to international studies of somewhat

older children (Hoff-Ginsberg 1998; High et al. 2000), there

Discussion

were no significant differences in vocabulary between children

of higher- and lower-educated mothers. The association

Main findings

between SES and vocabulary gets stronger in course of time

Good communication quality, low maternal age, female gender (e.g. Hoff-Ginsberg 1998; Landry et al. 2002), and the children

and frequent reading were significantly and independently studied here were only 17–19 months old. Another possible

associated with children’s expressive vocabulary. High maternal explanation could lie in the relatively equal social conditions

education, good communication quality, higher maternal age, in Sweden. Furthermore, according to other data from our

female gender and being a first-born child was significantly and extensive study, higher-educated mothers found their total

independently associated with frequent reading. Reading at workload to be heavier and their tasks more conflicting than

least 6 times/week added more than 0.3 SD in vocabulary, lower-eduacted mothers did, possibly resulting in reduced

regardless of gender and communication. Child difficultness opportunities for conversation. Highly educated mothers may

showed no associations with either vocabulary or reading. cultivate more demanding attitudes, both with regard to their

© 2008 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child: care, health and development, 34, 2, 257–266

Expressive vocabulary in 18-month-old children 263

Table 4. Shared reading by maternal

Dependent variable: shared reading

education, communication, maternal age,

child gender, child birth order and child Independent variable n <6 times/week ⱖ6 times/week P

difficultness

Maternal education (d.f. = 3) <0.0001

Primary or less 103 57.3 42.7

Secondary: 2 years 186 37.6 62.4

Secondary: 3 or 4 years 310 38.4 61.6

College or university 476 23.3 76.7

Communication (d.f. = 1)* <0.0001

Score >mean 569 24.4 75.6

Score ⱕmean 506 43.5 56.5

Maternal age (d.f. = 4) 0.2035

18–24 82 37.8 62.2

25–29 251 37.8 62.2

30–34 396 29.5 70.5

35–39 269 33.5 66.5

40–48 79 36.7 63.3

Child gender (d.f. = 1) 0.0033

Boys 542 37.8 62.2

Girls 541 29.4 70.6

Child birth order (d.f. = 1) <0.0001

First-born 497 23.5 76.5

Later-born 586 42.2 57.8

Child difficultness (d.f. = 1)† 0.7420

Score <mean 504 33.1 66.9

Score ⱖmean 578 34.1 65.9

Total 1083 33.6 66.4

Significance tests by c2. Observations with missing values excluded.

*High scores are favourable.

†Low scores are favourable.

Table 5. Multiple regression analysis with expressive vocabulary as the dependent variable

Standardized

Independent variable Parameter estimate Standard error estimate (b) t value Pr > t

Intercept 3.47395 6.76897 0 0.51 0.6079

Maternal education -0.41864 0.62275 -0.02048 -0.67 0.5016

Communication 4.69543 1.00254 0.14635 4.68 <0.0001

Maternal age -0.36580 0.13048 -0.09346 -2.80 0.0052

Child gender 9.05455 1.19637 0.22177 7.57 <0.0001

Child birth order -1.10198 1.38998 -0.02692 -0.79 0.4281

Child difficultness 0.37965 0.74420 0.01533 0.51 0.6101

Shared reading 3.57932 0.57869 0.19639 6.19 <0.0001

Both genders pooled together.

n = 1039. Adjusted R2 = 0.1291, d.f. = 7, F = 22.98, P < 0.0001.

children’s vocabulary and to the correctness of their own most frequently reading to their children. This hypothesis was

assessments. supported by our findings.

The SES in terms of maternal education turned out to be To our knowledge, our study is the only one analysing a

closely associated with reading frequency. This was not quite in possible connection between mother’s age and frequent

line with the results of Kuo and colleagues (2004), who found reading with children. The proportion frequently read to

that even among less underprivileged families, reading with reached a peak in maternal age group 30–34, after which it

young children was rather infrequent. re-declined (Table 4, not significant). When entered as a con-

Mothers’ communication showed the strongest association tinuous variable in the multiple regression analysis, however,

with shared reading. Karrass and colleagues (2003) have specu- maternal age resulted in a significant positive association with

lated that mothers with a good communication also are the ones reading (Table 6).

© 2008 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child: care, health and development, 34, 2, 257–266

264 M. Westerlund and D. Lagerberg

Table 6. Multiple regression analysis with shared reading as the dependent variable

Standardized

Independent variable Parameter estimate Standard error estimate (b) t value Pr > t

Intercept 0.28618 0.35867 0 0.80 0.4251

Maternal education 0.22957 0.03254 0.20299 7.05 <0.0001

Communication 0.42597 0.05182 0.24125 8.22 <0.0001

Maternal age 0.02756 0.00688 0.12733 4.00 <0.0001

Child gender 0.21939 0.06348 0.09734 3.46 0.0006

Child birth order 0.44216 0.07264 0.19559 6.09 <0.0001

Child difficultness -0.00458 0.03959 -0.00335 -0.12 0.9080

Both genders pooled together.

n = 1061. Adjusted R2 = 0.1688, d.f. = 6, F = 36.88, P < 0.0001.

Table 7. Mean sizes of expressive vocabulary for combinations of child gender and mother’s perceived communication, given that shared reading did

or did not occur six or more times/week

Shared reading <6 Shared reading ⱖ6

times/week times/week

Child gender and mother’s

perceived communication n Mean n Mean t P Effect size*

Boys

Communication less than good, ⱕmean 114 17.8 132 23.8 -2.72 0.0071 0.35

Communication good, >mean 83 21.4 198 30.0 -3.84 0.0002 0.46

Girls

Communication less than good, ⱕmean 102 25.6 150 35.2 -3.65 0.0003 0.47

Communication good, >mean 53 31.6 221 38.2 -2.12 0.0350 0.32

Effect sizes calculated as Cohen’s d with weighted SDs. Effect size 1 = one SD. Total n = boys: 546, girls: 545 (38 observations with missing values excluded).

*0.8 large, 0.5 medium and 0.2 small.

Contrary to the association between age and frequent reading, study when controlling for other independent variables

the relation between maternal age and expressive vocabulary was (Table 5). Apparently, the difference was explained by these

negative: younger mothers, who apparently read less with their other factors.

children, reported more words spoken by their children. The

explanation given by the regression analyses lies in the fact that

Methodological considerations

reading produced an additional contribution to word produc-

tion after controlling for maternal age and other independent It remains a matter of concern that the background and

variables. It remains to be explained why the association between outcome variables were not independent, all data being col-

child vocabulary and maternal age was negative, contrary to lected by maternal self-report. Self-report bias cannot be

findings reported by Pan and colleagues (2004). Mothers in their excluded. If, for instance, mothers who reported frequent shared

study were younger, however, than those included in our present reading also tended to overestimate systematically the quality of

sample (mean 23 years vs. 32 years). Younger mothers might be their communication with the children, the strong association

more eager to feel proud of their children and may energetically between communication and reading would be largely spuri-

search for signs of progress in their offspring. ous, as would the relation between communiction and vocabu-

Contrary to the findings of High and colleagues (1999), lary. We have had no possibility, in the present study, to

Karrass and colleagues (2003), and Roberts and colleagues safeguard against this.

(2005), we found girls to be significantly more involved in On the other hand, certain variables were of a ‘hard’ kind that

reading than boys (Tables 4 & 6). This does not appear to have should not cause great concern about reliability, i.e. year of birth,

been shown in earlier research. education, gender and birth order. Furthermore, the difficultness

A finding contrary to earlier studies (Hoff-Ginsberg 1998; scale applied is a well-tried and widely used instrument. The

Berglund et al. 2005) was the non-significant difference in SCS18 has shown good psychometric properties. The commu-

vocabulary between first- and later-born children in the present nication instrument, it is true, was developed ad hoc

© 2008 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child: care, health and development, 34, 2, 257–266

Expressive vocabulary in 18-month-old children 265

but showed a high alpha value (0.92). The variable measuring reaching parents and children. While awaiting more studies to

shared reading has not been tested as to reliability or validity and establish a causal relationship, we still wish to emphasize the

could be inaccurate. This is a shortcoming of the present study, importance of our findings. Good communication and frequent

but one that could hardly have been avoided, as it seems. reading give fuel to children’s language development, emergent

The present sample included a certain proportion of literacy and later reading skill.

immigrant families. We cannot tell whether these mothers

understood the SCS18 in the same way as Swedish mothers did. Acknowledgements

As pointed out by Kaplan and Bennett (2003), analyses based on

ethnicity may not always be relevant to the question under The study was supported by the Swedish Council for Working

study. In the case of linguistic matters, however, this does not Life and Social Research, the county council of Uppsala, the

seem to be true. Families stemming from other cultures may Gillberg Foundation and Allmänna Barnhuset. Sincere thanks

have different reading and conversation habits from those of the are due to all experiment and control nurses for their interest in

majority population, differences possibly influencing our the study and for their generous contribution in time and efforts.

results in uncontrolled ways. The proportion of immigrants was

rather small, however, and it was not feasible to make further

classifications by ethnicity. Key messages

It must be stressed that the present cross-sectional study did

Contrary to demographic factors, communication and

not permit conclusions about causes and effects. For instance, it

reading can be influenced and improved in parents of young

was found that girls were more often read to and had a more

children. Even if the variance in vocabulary explained by

advanced vocabulary than boys. Whether this was because of

reading habits was not large, a few per cent’s improvement

frequent reading or whether mothers read more to girls because

would be of high importance on the population level. More

of their richer vocabulary cannot be determined. In the same

research is needed to establish the causal paths by which

vein, the term ‘effect size’ should not be taken to imply any effect

reading is linked to language development. In the meantime,

proper, but is used here for convenience, being an established

we strongly recommend organizations working with parents

expression.

and children to develop methods for encouraging parents to

The proportion of the variance explained by the regression

communicate positively with their children and introduce

analyses amounted to no more than 13% for expressive vocabu-

them at an early age to the fascinating world of books.

lary and 17% for shared reading. Proportions of these magni-

tudes are not uncommon in social research. However, explained

variances of the sizes found may be quite considerable if viewed

References

from a public health perspective. Even small improvements of

only a few per cent in reading and vocabulary may be very Bates, J. E., Freeland, C. A. B. & Lounsbury, M. L. (1979) Measurement

substantial at the population level. of infant difficultness. Child Development, 50, 794–803.

Berglund, E. & Eriksson, M. (2000) Communicative development

in Swedish children 16–28 months old: the Swedish early

Conclusions communicative development inventory – words and sentences.

Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 41, 133–144.

The paramount findings of this study were the strong associa-

Berglund, E., Eriksson, M. & Westerlund, M. (2005) Communicative

tions of communication quality with both expressive vocabu- skills in relation to gender, birth order, childcare and

lary and reading frequency, and of reading frequency with socioeconomic status in 18-month-old children. Scandinavian

vocabulary – in addition to the contribution of communica- Journal of Psychololgy, 46, 485–491.

tion. Contrary to age, education, gender and birth order, Bornstein, M. H. & Haynes, O. M. (1998) Vocabulary competence in

reading and communication style are open to influence and early childhood: measurement, latent construct, and predictive

change. Parents of young children are highly motivated to validity. Child Development, 69, 654–671.

Bornstein, M. H., Haynes, O. M. & Painter, K. M. (1998) Sources of

receive information that may benefit their child’s development.

child vocabulary competence: a multivariate model. Journal of

Stimulating parents to observe, comment upon and encourage Child Language, 25, 367–393.

the child’s talking as well as reading together appears to be a Dixon, W. E. Jr & Smith, P. H. (2000) Links between early

highly relevant task for speech pathologists and professionals in temperament and language acquisition. Merrill Palmer Quarterly,

educational settings, healthcare services and other activities 46, 417–440.

© 2008 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child: care, health and development, 34, 2, 257–266

266 M. Westerlund and D. Lagerberg

Eriksson, M. & Berglund, E. (1999) Swedish early communicative Karrass, J., Braungart-Rieker, J. M., Mullins, J. & Burke Lefever, J.

development inventories: words and gestures. First Language, 19, (2002) Processes in language acquisition: the role of gender,

55–90. attention, and maternal encouragement of attention over time.

Eriksson, M., Westerlund, M. & Berglund, E. (2002) A screening Journal of Child Language, 29, 519–543.

version of the Swedish communicative development inventories Karrass, J., VanDeventer, M. C. & Braungart-Rieker, J. M. (2003)

designed for use with 18-month-old children. Journal of Speech, Predicting shared parent-child book reading in infancy. Journal of

Language, and Hearing Research, 45, 948–960. Family Psychology, 17, 134–146.

Fenson, L., Dale, P. S., Reznick, J. S., Thal, D. J., Bates, E., Hartung, J. Kirk, R. E. (1996) Practical significance: a concept whose time has

P., Pethick, S. & Reilly, J. S. (1993) The MacArthur Communicative come. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 56,

Development Inventories: Users Guide and Technical Manual. 746–759.

Singular Publishing Group, San Diego, CA, USA. Klass, P. E., Needlman, R. & Zuckerman, B. (2003) The developing

Fenson, L., Dale, P. S., Reznick, J. S., Bates, E., Thal, D. J. & Pethick, brain and early learning. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 88,

S. J. (1994) Variability in early communicative development. 651–654.

Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59, Kuo, A. A., Franke, T. M., Regalado, M. & Halfon, N. (2004)

1–189. Parent report of reading to young children. Pediatrics, 113,

Galsworthy, M., Dionne, G., Dale, P. & Plomin, R. (2000) Sex 1944–1951.

differences in early verbal and non-verbal cognitive development. Landry, S. H., Smith, K. E. & Swank, P. R. (2002) Environmental

Developmental Science, 3, 206–215. effects on language development in normal and high-risk child

Girolametto, L., Weitzman, E., Wiigs, M. & Steig Pearce, P. (1999) populations. Seminars in Pediatric Neurology, 9,

The relationship between maternal language measure and language 192–200.

development in toddlers with expressive vocabulary delays. Locke, A., Ginsborg, J. & Peers, I. (2002) Development and

American Journal of Speech Language Pathology, 8, 364–374. disadvantage: implications for the early years and beyond.

Golova, N., Alario, A., Viver, P., Rodriguez, M. & High, P. (1999) International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders,

Literacy promotion for Hispanic families in a primary care setting: 37, 3–15.

a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics, 5, 993–997. Magnusson, M. (1997) Rationality of routine health examinations by

Hart, B. & Risley, T. R. (1995) Intervention to equalize early physicians of 18-month-old children: experiences based on data

experience. In: Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of from a Swedish county. Acta Paediatrica, 86, 881–887.

Young American Children (eds B. Hart & T.R. Risley), pp. 191–219. Manolson, A. (1992) It Takes Two to Talk. A Parent’s Guide to Helping

Paul H. Bookers Publishing Co, Baltimore, MD, USA. Children to Communicate. The Hanen Centre, Toronto, ON,

High, P., Hopmann, M., LaGasse, L., Sege, R., Moran, J., Guiterrez, C. Canada.

& Becker, S. (1999) Child centered literacy orientation: a form of Pan, B. A., Rowe, M. L., Spier, E. & Tamis-Lemonda, C. (2004)

social capital? Pediatrics, 103: e55. Measuring productive vocabulary of toddlers in low-income

High, P., LaGasse, L., Becker, S., Ahlgren, I. & Gardner, A. (2000) families: concurrent and predictive validity of three sources of

Literacy promotion in primary care pediatrics: can we make a data. Journal of Child Language, 31, 587–608.

difference? Pediatrics, 105, 927–934. Roberts, J., Jurgens, J. & Burchinal, M. (2005) The role of home

Hoff, E. & Tian, C. (2005) Socioeconomic status and cultural literacy practices in preschool children’s language and emergent

influences on language. Journal of Communication Disorders, 38, literacy skills. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research,

271–278. 48, 345–359.

Hoff-Ginsberg, E. (1991) Mother-child conversation in different SAS Institute Inc. (1987) SAS/STATIM Guide for Personal Computers,

social classes and communicative settings. Child Development, 62, Version 6 Edition. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc., 1987.

782–796. Scarborough, H. S. & Dobrich, W. (1994) On the efficacy of reading

Hoff-Ginsberg, E. (1998) The relation of birth order and to preschoolers. Developmental Review, 14, 245–302.

socioeconomic status to children’s language experience and Sundelin, C., Magnusson, M. & Lagerberg, D. (2005) Child Health

language development. Applied Psycholinguistics, 19, 603–629. Services in transition: I. Theories, methods and launching. Acta

Hundeide, K. (1996) Ledet Samspill: Håndbok til ICDPS Paediatrica, 94, 329–336.

Sensitiviseringsprogram [Guided Interaction: Manual of the ICDP’s Whitehurst, G. & Lonigan, C. (2001) Emergent literacy: development

Sensitivity Program]. International Child Development Programs. from prereaders to readers. In: Handbook of Early Literacy Research,

Vett & Viten, Nesbru, Norway. Vol. 1 (eds S. Neuman & D. Dickinson), pp. 11–29. The Guilford

Jones, C. P. & Adamson, L. B. (1987) Language use in mother–child Press, New York, NY, USA.

and mother–child–sibling interactions. Child Development, 58, Whitehurst, G., Falco, F., Lonigan, C., Fischel. J., DeBaryshe, B. &

356–366. Valdez-Menchaca, M. (1988) Accelerating language development

Kaplan, J. B. & Bennett, T. (2003) Use of race and ethnicity in through picture book reading. Developmental Psychology, 24,

biomedical publication. Journal of American Medical Association, 552–559.

289, 2709–2716.

© 2008 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child: care, health and development, 34, 2, 257–266

You might also like

- Vocabulary InterventionDocument22 pagesVocabulary InterventionChrysa PetridouNo ratings yet

- Communication in Marriage Reed 105Document28 pagesCommunication in Marriage Reed 105Erwin Y. CabaronNo ratings yet

- Raising Bilingual Children English SpanishDocument6 pagesRaising Bilingual Children English SpanishjoangopanNo ratings yet

- Cookery1-SPECIALIZED-FINAL 1Document37 pagesCookery1-SPECIALIZED-FINAL 1Princess Aira Malveda100% (1)

- Baby Talk PDFDocument8 pagesBaby Talk PDFmrouhaneeNo ratings yet

- DLP Eng3 - q3 Cot 2 Giving Possible Solutions To A ProblemDocument6 pagesDLP Eng3 - q3 Cot 2 Giving Possible Solutions To A ProblemNardita Castro100% (1)

- Broselow Pediatric Emergency TapeDocument13 pagesBroselow Pediatric Emergency TapePaulo KaleNo ratings yet

- Dialogic ReadingDocument12 pagesDialogic Readingmagar telvNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary: de V Elopi NGDocument12 pagesVocabulary: de V Elopi NGamna qadirNo ratings yet

- Emergent Literacy Intervention For Vulnerable PresDocument14 pagesEmergent Literacy Intervention For Vulnerable PresMary Jane CatubayNo ratings yet

- Beyond The Pages of A Book Interactive Book ReadinDocument9 pagesBeyond The Pages of A Book Interactive Book ReadinasnoviantiNo ratings yet

- The Impact of A Dialogic Reading Program On Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Kindergarten and Early Primary School-Aged Students in Hong KongDocument14 pagesThe Impact of A Dialogic Reading Program On Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Kindergarten and Early Primary School-Aged Students in Hong Kongp.ioannidiNo ratings yet

- Developmental Science - 2003 - Liu - An Association Between Mothers Speech Clarity and Infants Speech DiscriminationDocument10 pagesDevelopmental Science - 2003 - Liu - An Association Between Mothers Speech Clarity and Infants Speech DiscriminationCamilla OelfeldNo ratings yet

- Child Development - 2003 - Hoff - The Specificity of Environmental Influence Socioeconomic Status Affects Early VocabularyDocument11 pagesChild Development - 2003 - Hoff - The Specificity of Environmental Influence Socioeconomic Status Affects Early VocabularyGamal MansourNo ratings yet

- Talking With Young Children: How Teachers Encourage LearningDocument12 pagesTalking With Young Children: How Teachers Encourage LearningkathirNo ratings yet

- Ingilizce Makale Dil GelişimiDocument13 pagesIngilizce Makale Dil GelişimimuberraatekinnNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0271530916300945 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0271530916300945 MainMppaolantonio PaolantonioNo ratings yet

- Mcleod 2009Document17 pagesMcleod 2009TASA LAURIKA -No ratings yet

- Exposure To Multiple Languages Enhances Communication SkillsDocument21 pagesExposure To Multiple Languages Enhances Communication SkillsWiktoria KazimierczakNo ratings yet

- Older Siblings' Influence on Language in Bilingual HomesDocument18 pagesOlder Siblings' Influence on Language in Bilingual HomesTinaNo ratings yet

- Children S Knowledge of Multiple Word MeDocument39 pagesChildren S Knowledge of Multiple Word Mevqra dimitrovaNo ratings yet

- Schooling Effects HearingDocument24 pagesSchooling Effects HearingIustina SolovanNo ratings yet

- Language Delays Reading Delays and Learning DifficDocument12 pagesLanguage Delays Reading Delays and Learning DifficManal Gomaa - منال جمعةNo ratings yet

- Haebig - Et.al 2013 AJSLP-language-TEA PDFDocument25 pagesHaebig - Et.al 2013 AJSLP-language-TEA PDFDora GranadosNo ratings yet

- 2013 - Ramirez, Lieberman & MayberryDocument22 pages2013 - Ramirez, Lieberman & MayberryjoaopaulosantosNo ratings yet

- Bilingual parenting myths and scientific factsDocument15 pagesBilingual parenting myths and scientific factsHelen FannNo ratings yet

- Shared Book Reading by Parents With Young Children PDFDocument7 pagesShared Book Reading by Parents With Young Children PDFjiyaskitchenNo ratings yet

- Reese 20 and 20 Cox 20 ArticleDocument10 pagesReese 20 and 20 Cox 20 ArticleClaudia Cristine CondriucNo ratings yet

- Haebig - Et.al 2013 AJSLPDocument26 pagesHaebig - Et.al 2013 AJSLPIgnacio WettlingNo ratings yet

- Phonological Awareness and Bilingual Preschoolers: Should We Teach It And, If So, How?Document7 pagesPhonological Awareness and Bilingual Preschoolers: Should We Teach It And, If So, How?Diana DiazNo ratings yet

- 03 Catherine MIMEAU1 Fuente 2 The Bidirectional Association Between Maternal 2 AñosDocument23 pages03 Catherine MIMEAU1 Fuente 2 The Bidirectional Association Between Maternal 2 AñosFlor De Maria Mikkelsen RamellaNo ratings yet

- Priming Young Children For Language and Literacy Success: Lessons From ResearchDocument4 pagesPriming Young Children For Language and Literacy Success: Lessons From ResearchAnindita PalNo ratings yet

- Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise SpecifiedDocument7 pagesPervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise SpecifiedAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Visions For Literacy: Parents' Aspirations For Reading in Children With Down SyndromeDocument8 pagesVisions For Literacy: Parents' Aspirations For Reading in Children With Down SyndromeValee ValentinaNo ratings yet

- An Association Between Phonetic Complexity of InfaDocument8 pagesAn Association Between Phonetic Complexity of Infal.fernandezNo ratings yet

- 04 Texto - Lisa BaumwellDocument12 pages04 Texto - Lisa BaumwellFlor De Maria Mikkelsen RamellaNo ratings yet

- 2-Cheungetal 2019Document7 pages2-Cheungetal 2019Andreas RouvalisNo ratings yet

- Child Code-Switching and Adult Content ContrastsDocument18 pagesChild Code-Switching and Adult Content ContrastsBatrisyia MazlanNo ratings yet

- Tel InglesDocument4 pagesTel InglesElizabeth Bernal PonceNo ratings yet

- 2017 Ramirez-Esparza - Etal - ChildDevDocument19 pages2017 Ramirez-Esparza - Etal - ChildDevLara Marina MusleraNo ratings yet

- Shared Book Reading by Parents With Young ChildrenDocument7 pagesShared Book Reading by Parents With Young ChildrenZuriyatini Hj ZainalNo ratings yet

- Undergrad Thesis DeoliveiraDocument26 pagesUndergrad Thesis Deoliveiraapi-322682360No ratings yet

- Pathways To Literacy: Connections Between Family Assets and Preschool Children's Emergent Literacy SkillsDocument18 pagesPathways To Literacy: Connections Between Family Assets and Preschool Children's Emergent Literacy Skillsapi-277160707No ratings yet

- Rowe JCL 2008Document22 pagesRowe JCL 2008bolinha com um BNo ratings yet

- Parental Motivation Key to Minority Language AcquisitionDocument59 pagesParental Motivation Key to Minority Language Acquisitionkarim ghazouaniNo ratings yet

- Infant-Language, Shyness and SocialContextDocument9 pagesInfant-Language, Shyness and SocialContextJuan Lino Fernandez GonzalezNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Morphological Awareness On The Literacy Development of First-Grade ChildrenDocument14 pagesThe Influence of Morphological Awareness On The Literacy Development of First-Grade ChildrenCatnis TomNo ratings yet

- Naigles 2013Document13 pagesNaigles 2013Yunhui ChenNo ratings yet

- Getting It Right From The StartDocument5 pagesGetting It Right From The StartDÉBORA DRUMNo ratings yet

- Socioeconomic Influences On Children's Language Acquisition Incidences Socioeconomiques Sur L'acquisition Langage Chez Les EnfantsDocument12 pagesSocioeconomic Influences On Children's Language Acquisition Incidences Socioeconomiques Sur L'acquisition Langage Chez Les EnfantsAzam KhujamyorovNo ratings yet

- 01 Catherine S. Tamis-LeMonda, Marc H. Bornstein, and Lisa Baumwell 2001Document21 pages01 Catherine S. Tamis-LeMonda, Marc H. Bornstein, and Lisa Baumwell 2001Flor De Maria Mikkelsen RamellaNo ratings yet

- Le Monda, Vallonton 2019 El Ambiente de Aprendizaje Temprano en El Hogar Predice Las Habilidades Académicas de Los Niños de Quinto Grado.Document18 pagesLe Monda, Vallonton 2019 El Ambiente de Aprendizaje Temprano en El Hogar Predice Las Habilidades Académicas de Los Niños de Quinto Grado.pilarNo ratings yet

- Late Language Emergence at 24 Months: An Epidemiological Study of Prevalence, Predictors, and CovariatesDocument31 pagesLate Language Emergence at 24 Months: An Epidemiological Study of Prevalence, Predictors, and CovariatesErsya MuslihNo ratings yet

- Conti Ramsden2008Document13 pagesConti Ramsden2008Guido Bello CabreraNo ratings yet

- Psycholinguistic - Language Development in Infancy and Early Childhood - Group 9Document12 pagesPsycholinguistic - Language Development in Infancy and Early Childhood - Group 9Tazqia Aulia ZakhraNo ratings yet

- Caretaker Talk - Apr 8, 2023Document3 pagesCaretaker Talk - Apr 8, 2023Nguyễn Ngọc PhượngNo ratings yet

- Schwab and Lew-Williams (2016) - Language Learning, Socioeconomic Status, and Child-Directed SpeechDocument17 pagesSchwab and Lew-Williams (2016) - Language Learning, Socioeconomic Status, and Child-Directed SpeechMariana MuttoniNo ratings yet

- What Automated Vocal Analysis Reveals About The Vocal Production and Language Learning Environment of Young Children With AutismDocument15 pagesWhat Automated Vocal Analysis Reveals About The Vocal Production and Language Learning Environment of Young Children With AutismEthan Angelo Brante DonosoNo ratings yet

- ArticolDocument12 pagesArticolEunice LuncanNo ratings yet

- Bowne RelationshipsTeachersLanguage 2017Document25 pagesBowne RelationshipsTeachersLanguage 2017Umme HabibaNo ratings yet

- Readingaloudtochildren Adc July2008Document4 pagesReadingaloudtochildren Adc July2008api-249811172No ratings yet

- DeHouweretal2014 - MonoVsBilingVocabSizeDocument23 pagesDeHouweretal2014 - MonoVsBilingVocabSizeVera TraNo ratings yet

- Parental Involvement in The Development of Children's Reading Skill: A Five-Year Longitudinal StudyDocument16 pagesParental Involvement in The Development of Children's Reading Skill: A Five-Year Longitudinal StudyNurul Syazwani AbidinNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Comprehension and Meaning in LanguageFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Comprehension and Meaning in LanguageNo ratings yet

- Paternal Love EssayDocument2 pagesPaternal Love Essayfhlorievy langomezNo ratings yet

- List of Allianz Efu Network (Panel) Hospitals: Hospital Name Address Telephone # KarachiDocument6 pagesList of Allianz Efu Network (Panel) Hospitals: Hospital Name Address Telephone # KarachiFaizan BasitNo ratings yet

- Curriculam Vitae: ObjectiveDocument5 pagesCurriculam Vitae: ObjectiveGokul RajNo ratings yet

- Seligman Attributional Style QuestionnaireDocument14 pagesSeligman Attributional Style QuestionnaireAnjali VyasNo ratings yet

- Chrome Lignosulfonate (CLS)Document5 pagesChrome Lignosulfonate (CLS)sajad gohariNo ratings yet

- BT-740 OP Manual (740-ENG-OPM-EUR-R02) PDFDocument50 pagesBT-740 OP Manual (740-ENG-OPM-EUR-R02) PDFJaneth Pariona SedanNo ratings yet

- Concept Map - SepsisDocument9 pagesConcept Map - SepsismarkyabresNo ratings yet

- EMP 412 - Teaching - Notes - Topic - 1 - Economics - of - Education - and - Human - Capital - Theory - 1Document17 pagesEMP 412 - Teaching - Notes - Topic - 1 - Economics - of - Education - and - Human - Capital - Theory - 1Saka FelistarNo ratings yet

- Narrative ReportDocument2 pagesNarrative ReportRhisia RaborNo ratings yet

- ANA MAPEH S2017 Ans KeyDocument15 pagesANA MAPEH S2017 Ans KeyVan Errl Nicolai SantosNo ratings yet

- The Corporation Reflection PaperDocument3 pagesThe Corporation Reflection PaperDevadutt M.SNo ratings yet

- De-Escalation - Aggression Management TechniquesDocument14 pagesDe-Escalation - Aggression Management Techniquesparis emmaNo ratings yet

- Scissor Lift ProcedureDocument2 pagesScissor Lift ProcedureAdhi LatifNo ratings yet

- Sports Medicine 10-Lesson 4 - Lower Leg Muscles Turf ToeDocument5 pagesSports Medicine 10-Lesson 4 - Lower Leg Muscles Turf Toeapi-383568582No ratings yet

- B NursingDocument10 pagesB NursingAyeshia OliverNo ratings yet

- Rts Medicines 7778-1Document79 pagesRts Medicines 7778-1sam yadavNo ratings yet

- Pengumuman Jadwal Rapid Test Antigen Gratis Bagi Peserta Ujian SKB CPNS Pemerintah Kota Pangkalpinang 2021Document16 pagesPengumuman Jadwal Rapid Test Antigen Gratis Bagi Peserta Ujian SKB CPNS Pemerintah Kota Pangkalpinang 2021Syahrul SalehNo ratings yet

- Breastfeeding Benefits and RecommendationsDocument46 pagesBreastfeeding Benefits and RecommendationsPriya bhattiNo ratings yet

- SBFP Form 1 2021 Cebu Province Tubod Elementary SchoolDocument23 pagesSBFP Form 1 2021 Cebu Province Tubod Elementary SchoolJane Rodriguez LumacangNo ratings yet

- Abbott PIMA CD4 BR NewDocument2 pagesAbbott PIMA CD4 BR NewangelinaNo ratings yet

- Safety and Influence of A Novel Powder Form of Coconut Inflorescence Sap On Glycemic Index and LipidDocument1 pageSafety and Influence of A Novel Powder Form of Coconut Inflorescence Sap On Glycemic Index and LipidPriscila CerqueiraNo ratings yet

- Mini Test 2Document2 pagesMini Test 2Thùy DươngNo ratings yet

- The Disabled Throwing Shoulder: Spectrum of Pathologyd10-Year UpdateDocument47 pagesThe Disabled Throwing Shoulder: Spectrum of Pathologyd10-Year UpdateSandro RolimNo ratings yet

- ABP - MPDO Lakkireddy Palli Mandal Approved LetterDocument3 pagesABP - MPDO Lakkireddy Palli Mandal Approved Letterchild development project officer lakkireddypalliNo ratings yet

- GTLMH student evaluationDocument2 pagesGTLMH student evaluationabcalagoNo ratings yet

- PROCESS - Risk Assessment & HACCP Planning: Section 7.4.1Document4 pagesPROCESS - Risk Assessment & HACCP Planning: Section 7.4.1Wisnu samuel Atmaja triwarsitaNo ratings yet