Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Barnhill 2001

Uploaded by

Lia C CriscoulloOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Barnhill 2001

Uploaded by

Lia C CriscoulloCopyright:

Available Formats

Focus on Autism and Other

Developmental Disabilities http://foa.sagepub.com/

Social Attributions and Depression in Adolescents with Asperger Syndrome

Gena P. Barnhill

Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl 2001 16: 46

DOI: 10.1177/108835760101600112

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://foa.sagepub.com/content/16/1/46

Published by:

Hammill Institute on Disabilities

and

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://foa.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://foa.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

>> Version of Record - Jan 1, 2001

What is This?

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on November 30, 2014

Social Attributions and

Depression in Adolescents with

Asperger Syndrome

Gena P. Barnhill

This study investigated the relationship between level of depressive symptoms and so- the environmental demands. Szatmari de-

cial attributions in 33 adolescents with Asperger syndrome. Results revealed a signifi- scribed them as always &dquo;out of context&dquo;

cant positive relationship between depressive symptoms and ability attributions for (p. 83).

social failure, suggesting that interventions may need to focus on teaching these indi- According to Attwood (1998), &dquo;Peo-

viduals to attribute social failure to causes other than ability. In addition, it was found ple with Asperger’s syndrome perceive

that the more intelligent the individual, the less he or she attributed social success to the world differently from everyone else&dquo;

chance and task difficulty factors, and vice versa. It is hypothesized that more intelli-

(p. 9). Robinson and Trower (1988) ar-

gent participants might have developed increased cognitive awareness that more that social behavior is the most

gued

complex or multiple factors are involved in social success, rather than simply luck central and important characteristic of

or chance. Findings are discussed relative to implications for practitioners.

human beings. Given this assertion, indi-

viduals with Asperger syndrome appear

to be at a distinct disadvantage in coping

sperger syndrome is a develop- take part in reciprocal communication, with their social world. According to

mental disability marked by im- and do not seem to understand the Tantam ( 1991 ), Asperger syndrome may

~- pairments in social relationships unwritten rules of communication and cause the greatest disability in adoles-

and in verbal and nonverbal communica- conduct (Attwood, 1998; Frith, 1991; cence and young adulthood, when social

tion and by restrictive, repetitive patterns Myles & Simpson, 1998). Children and relationships are the key to almost every

of behavior, interests, and activities. Al- youth with Asperger syndrome not only achievement. Wing (1981) noted that it

though this syndrome was recognized in are socially isolated but also demonstrate is at this time that clinically diagnosable

1944 by Hans Asperger of Austria, the an abnormal range or type of social in- depression and anxiety occur, which may

American Psychiatric Association (APA) teraction that cannot be explained by be related to a painful awareness of social

did not recognize Asperger syndrome as other factors such as shyness, short at- differences. More recently, clinical re-

a specific pervasive developmental disor- tention span, aggressive behavior, or lack ports and research have revealed that

der until 1994. Given this recent official of experience in a given area (Szatmari, adolescents and adult individuals with

recognition of Asperger syndrome, there 1991). These impairments may manifest Asperger syndrome appear to be at risk

is a dearth of research regarding individ- in different ways. For example, the child for depression (Ghaziuddin, Weidmer-

uals with this disorder. It is known that may not show any interest in other chil- Mikhail, & Ghaziuddin, 1998; Tantam,

Asperger syndrome &dquo;profoundly limits a dren, be a passive participant in other 1991). Additionally, there is a genuine

child’s participation in the process of children’s play, or interact with other risk of suicide (Wolff, 1995). Yet, this is

growing up&dquo; (Szatmari, 1991, p. 91). Al- children only when play involves his or an understudied phenomenon in chil-

though some professionals consider As- her own obsessive interests. These chil- dren and adolescents with developmen-

perger syndrome to be a milder form of dren and youth may be very socially in- tal and learning disabilities (Hardan &

autism in terms of the apparent severity trusive or awkward, ask inappropriate Sahl, 1999; Rourke, Young, & Leenaars,

of its symptoms, it is a highly disabling questions, come too close to others, or 1989).

condition (Tantam, 1991). remain aloof. The key problem is not that Attributional or explanatory style (the

Individuals with Asperger syndrome they are socially isolated but that they causes people give for events in their

lack social skills, have a limited ability to cannot change their behavior to meet lives) has been studied to understand de-

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on November 30, 2014

47

pression and shed light on how people Method bus (1984) and Bell and McCallum

process information (DeMoss, Milich, & (1995) asserted that there were no

DeMers, 1993). Given the plethora of Participants widely used instruments adequate as

research that indicates there is a corre- measures of individual differences in self-

The 33 participants in this study were

lation between attributional styles and attributions, especially in the social do-

obtained from the Asperger syndrome

depression in children and adolescents database held by the special education main. Therefore, Bell and McCallum

(e.g., Gladstone & Kaslow, 1995), stud- department at a large midwestern uni- ( 1995 ) developed the SSAS to measure

ies are needed to determine if this students’ perceptions of the causes of

versity. All participants had an official di-

relationship exists for individuals with agnosis of Asperger syndrome rendered

their school-related social success and

Asperger syndrome. It is imperative to failure. The most current version consists

determine if these individuals have a so-

by a psychologist, psychiatrist, or physi- of 16 subscales (S. M. Bell, personal

cian. The 30 male and 3 female adoles-

cial attributional style that may put them communication, January 27, 1999).

cents ranged in age from 12 years 1

at risk for depression. Furthermore, con- Eight of the scales result from the facto-

month to 17 years 7 months (M 14 =

sidering Bandura’s (1982) statement that 6

years months; SD 1.68 years). Thirty-

=

rial combination of two aspects in the

individuals’ beliefs about the causes of school social domain: outcome (S suc- =

two of the adolescents were Caucasian,

their successes and failures mediate their and one was African American. Their cess, F =

failure) and attribution (A =

behavior by determining what action ability, E effort, C chance, and T

= = =

IQs, as measured by an individually ad-

they attempt to carry out and how much ministered intelligence test, ranged from task difficulty). These eight factors are

effort they put into this performance, an 71 to 144, with a mean IQ of 99.19 for Success/Ability (SA), Success/Effort

investigation of the social attributions of 32 of the participants. One adolescent (SE), Success/Chance (SC), Success/

individuals with Asperger syndrome may did not have an individual IQ score; Task Difficulty (ST), Failure/Ability

assist in understanding their social and (FA), Failure/Effort (FE), Failure/

however, he was participating success-

motivational patterns. This information Chance (FC), and Failure/Task Diffi-

fully in the grade-level curriculum at

appears to be essential for the design of school (see Table 1). culty (FT). The Internal/Success (IS)

effective interventions, social skills train- Twelve participants received counsel- subscale is calculated by adding the SA

ing, and attributional retraining to sup- ing or psychotherapy, 2 received speech/

and SE scores, and the External Success

port such persons in their everyday func- language services, and 4 received occu- (ES) subscale is calculated by adding the

tioning. In addition, preventive efforts pational therapy services (see Table 1).

SC and ST scores. The Internal/Failure

could then be designed and implemented (IF) subscale is calculated by adding the

before these individuals experience an

Thirty-one of the 33 participants were FA and FE scores, and the External/

emotional crisis.

being treated with anti-depressant, anti- Failure (EF) subscale is calculated by

anxiety, anti-psychotic, or anti-manic

Barnhill and Myles (2000) reported a adding the FC and FT scores. The

drugs; stimulants; or other physician-

relationship between general attribu- prescribed medications for behaviors re- Optimism/Success (OS) subscale is cal-

tional style, as measured by the Chil- lated to Asperger syndrome. Participants culated by adding the SA, SE, and SC

dren’s Attributional Style Questionnaire scores. The Pessimism/Failure (PF) sub-

reported taking one to six of these med-

(Seligman et al., 1984), and depression ications to control their behavior (M =

scale is calculated by adding the FA, FE,

in adolescents with Asperger syndrome. and FT scores. A total Success score (S)

2.36, SD = 1.37).

However, no research published to date is calculated by adding the SA, SC, SE,

specifically examines the relationship be- and ST scores together. Finally, a total

tween depression and social attributional

Instruments Failure score (F) is calculated by adding

or explanatory style in these persons. The Student Social Attribution Scale the FA, FC, FE, and FT scores. The

Given that social behavior is considered (SSAS; Bell & McCallum, 1995), and the questionnaire consists of 30 written sce-

to be a central characteristic of humans Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; narios that depict the participant experi-

(Robinson & Trower, 1988) and is an Kovacs, 1992) were administered indi- encing social success or failure followed

area of extreme difficulty for individuals vidually to each participant. Permission by the four randomly ordered causes of

with Asperger syndrome, it is imperative to use the SSAS was obtained from the ability, effort, chance, and task difficulty,

to explore their social attributions so that authors, whereas the CDI, a standard- from which the student has to choose

appropriate interventions can be de- ized instrument, was purchased for use in how often these causes apply to him or

signed to assist them in coping in the so- this study. In addition, demographic in- her (e.g., often, sometimes, or seldom).

cial world. Hence, the purpose of this formation was obtained for each ado- Alpha reliabilities reported for the 16

study was to investigate the relationship lescent. subscales of the newest version of the

between level of depressive symptoms SSAS were higher than those reported

and social attributions in adolescents Student Social Attribution Scale. for the 12-scenario version of the SSAS.

with Asperger syndrome. Marsh, Cairns, Relich, Barnes, and De- The most recent coefficients alpha were

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on November 30, 2014

48

dromes and other scales, and replicated

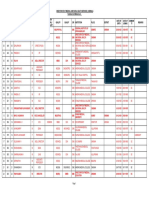

TABLE 1

Characteristics of Participants:

predictive relationships. Cronbach’s alpha

Demographic Summary in the normative sample equaled .86, in-

dicating good internal consistency relia-

bility. Alpha coefficients for the five fac-

tors ranged from .59 to .68 and were

considered to be in the acceptable range

for short factor subscales. Alpha coeffi-

cients have been reported in various

other research samples as ranging from

.71 to .89, indicating good internal con-

sistency.

Kovacs (1992) reported that the CDI

has acceptable test-retest reliability.

However, the selection of an appropriate

test-retest interval is problematic because

the CDI reportedly measures a state

rather than a trait. A two-week test-retest

interval was suggested. The CDI is a

valid instrument in that it assesses im-

portant constructs that have strong ex-

planatory and predictive usefulness in the

characterization of depressive symptoms

in children and adolescents.

Design and Procedure

This research project was a descriptive

study designed to explore the relation-

ship between social attributions and level

Note. Raw data are presented. Percentages are in parentheses. Results under &dquo;Current treatment&dquo; do of depression of adolescents with As-

not add to 100% because some participants received no treatments and others received more than one

perger syndrome. All of the identified ado-

treatment.

lescents with Asperger syndrome from

the Asperger syndrome database held at

follows: SA, .84; SE, .85; SC, .87; ST, the special education department at a

as severity measure, the CDI quantifies the

.82; FA, .84; FE, .86; FC, .76; FT, .76; magnitude of the depressive complaints. large midwestern university were invited

to participate in the research. Written per-

S, .92; 1/S, .89; E/S, .90; F, .93; I/F, It also can be used as a measure of change

to determine if the severity of depressive

mission to participate was obtained from

.91; E/F, .85; O/S, .87; P/F, .92 (S. M.

the parents of 33 of the 34 adolescents

Bell, personal communication, January symptoms has changed following treat-

invited to participate. The SSAS and CDI

27, 1999). Bell and McCallum (1995) ment. The scale provides a total CDI

were administered individually by the

reported that factor analysis and reliabil- score and the following five factor scores:

researcher to each adolescent to ensure

ity estimates for their shortened version Negative Mood, Interpersonal Problems,

that instructions were understood.

of the SSAS (12-scenario) provided evi- Ineffectiveness, Anhedonia, and Neg-

dence for the reliability and construct va- ative Self-Esteem. The normative sample

lidity of the scale. was divided into two groups based on Results

age: younger children, ages 7 to 12, and

Children’s Depression Inventory. older children, ages 13 to 17. Separate The following research questions were

The CDI is a 27-item self-rated depres- norms were developed for boys and girls. addressed:

sive symptom inventory designed for Kovacs (1992) reported numerous

school-age children 7 to 17 years old. psychometric studies on the CDI, which 1. Is there relationship between de-

a

The CDI’s readability is at the first-grade has been used extensively in clinical situ- pressive symptoms (total score on

level. The scale allows the child to choose ations. The literature supports sufficient the Children’s Depression Inven-

from among three alternatives that vary temporal reliability, internal consistency, tory) and social attributions (as

in the symptom described. As a symptom consistent correlations with various syn- measured by the Student Social

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on November 30, 2014

49

Attribution Scale) in individuals ages

12 to 18 diagnosed with Asperger TABLE 2

Total CDI Scores for Participants and Interpretive Guidelines

syndrome?

2. Is there a relationship between social

attributions (as measured by the Stu-

dent Social Attribution Scale) and in-

tellectual level in individuals ages 12

to 18 diagnosed with Asperger syn-

drome ?

3. Is there a relationship between social

attributions (as measured by the Stu-

dent Social Attribution Scale) and

age in individuals ages 12 to 18 di-

agnosed with Asperger syndrome?

Research Question One

Note. CDI =

Children’s Depression Inventory. Raw data are presented. Percentages are in parentheses.

Forty-six percent of the participants with *Compared to children of similar age and gender in the CDI normative sample.

Asperger syndrome rated themselves as

having depressive symptoms that fell Four statistically significant relation- There were no significant correlations

within the average range when compared

to peers of the same gender and age in

ships were found between the SSAS fac- found between age and any of the scale

tors and participants’ IQ scores (see or factor scores on the SSAS. Therefore,

the CDI normative group, whereas 18%

Table 4). A weak negative relationship social attributions, as measured by the

rated themselves as having more depres-

sive symptoms and 36% as having fewer

( r -.384, p < .05) was found between

=

SSAS, were not found to be related to

the total Success factor (sum of Success age for adolescents with Asperger syn-

depressive symptoms than peers (see Chance, Success Ability, Success Effort, drome in this study.

Table 2). The participants’ self-reported

and Success Task) and IQ. Somewhat

scores on the SSAS fell within 1 standard

deviation of scores previously reported stronger relationships were found be-

tween the Success Task factor and IQ Discussion

by S. Bell (personal communication, Jan- (r =

-.484, p < .05) and the Success

uary 31, 1999). Chance factor and IQ ( r -.427, p <

The 16 SSAS factor scores and the

=

Relationship of Findings to

total CDI score were compared using the .05). The lower the participant’s IQ, the Prior Studies

more likely it was that he or she attrib-

Pearson product-moment correlation

uted success to chance or task factors, Despite research that indicates explana-

(see Table 3). Two significant positive re- and the higher the participant’s IQ the torystyle is a stable trait (Burns & Selig-

lationships were revealed. A relationship less likely that he or she attributed suc- man, 1989; Nolen-Hoeksema, Girgus, &

in the low positive range ( v~ .400, p <

=

cess to chance or task factors. In addi- Seligman, 1986; Seligman et al., 1984),

.05) was found between the Internal tion, a close-to-moderate negative rela- other researchers have found that reattri-

Failure Factor (sum of Failure Ability and

tionship was found between the SSAS bution training is a successful interven-

Failure Effort) and the total CDI score.

External Success factor (sum of Success tion strategy with individuals who display

Similarly, a low positive correlation ( viz

=

Chance and Success Task) and IQ score a maladaptive or learned helplessness style

.398, p < .05 ) was revealed between the related to academic and social failures

Failure Ability Factor and total CDI ( r -.489, p < .05). The lower the par-

=

score.The more depressive symptoms re- ticipant’s IQ, the more he or she attrib- (Aydin, 1988; DeRubeis & Hollon, 1995;

uted social success to task and chance Dweck, 1975). Attribution retraining is

ported, the more the participants attrib- (external factors). Likewise, the higher a cognitive training approach explicitly

uted social failure to their ability and to

the sum of their ability and effort.

the participant’s IQ, the less he or she at- designed to change maladaptive attribu-

tributed social success to task and chance. tions. Attribution retraining might be con-

sidered as an intervention strategy for

individuals with Asperger syndrome.

Research Question Two Research Question Three

However, given the rigidity and lack of

Is there a

relationship between social at- Is there a relationship between social at- flexibility typical of individuals with As-

tributions (as measured by the SSAS) and tributions (as measured by the SSAS) and perger syndrome (Attwood, 1998), the

intellectual level in individuals ages 12 to age in individuals ages 12 to 18 diag- development of a maladaptive style in

18 diagnosed with Asperger syndrome? nosed with Asperger syndrome? these individuals is of significant concern.

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on November 30, 2014

50

cess and persisted at the task. Inter-

TABLE 3 TABLE 4

Correlations Between SSAS Factor Correlations Between SSAS Factor

ventions designed to alter their

were

Scales and Total CDI Score Scales and IQ Scores believing that their personal behaviors

did not affect achievement outcomes to

believing that they could affect outcomes.

Further research is needed to determine

if this form of attribution retraining is ap-

plicable to social attributions and to in-

dividuals with Asperger syndrome.

Implications from Descriptive

Attributional Data

Descriptive data also indicated that the

mean scores obtained on the attribu-

tional measures by participants with As-

perger syndrome fell within 1 standard

deviation of the scores obtained by the

norm groups as reported by the authors

of the SSAS (S. M. Bell, personal com-

munication, January 31, 1999). This is

encouraging because it suggests that in-

terventions for normally developing

*p < .05. *p < .05. peers may be helpful for individuals with

Asperger syndrome. Despite the unique

characteristics of individuals with Asper-

For example, it may be extremely diffi- with medication would be an effective in-

ger syndrome, these results suggest that

cult for persons with Asperger syndrome tervention approach for these individuals.

when they are considered as a group,

to change their pattern of pessimistic

they are also similar to other children and

thinking even with intensive cognitive re-

training because of their tendency to pre-

Relationship Between Social youth on other qualities, such as attribu-

Attributions and Depression tions. No data are available to indicate

fer routines and act in a rigid or ritualis-

how closely Bell’s norms for fourth-

tic manner. Results indicated that the more partici-

through sixth-grade students parallel the

As indicated in Table 1, 70% of the pants attributed social failure to their norms for adolescents. However, consid-

participants were being treated with anti- ability or to the sum of their ability and ering that Asperger syndrome is a devel-

depressant medication at the time of the effort, the higher was their depressive

opmental disability that affects social and

study. Medication may be effective in symptoms score. Inversely, the less they emotional development, these norms

treating depressive symptoms for adoles- attributed social failure to their ability or

may be applicable and appropriate for

cents with Asperger syndrome given that to the sum of their ability and effort, the

consideration with chronologically older

only 9% of this sample scored in the lower was their depressive symptoms

individuals.

above-average range (T-scores 61-65) score. These results have implications for

and none scored in the statistically sig- attribution retraining. Lack of ability is

nificant range (T-score > 70) on the CDI, considered an internal, stable, and global Relationship Between Social

which measures depressive symptoms. In attribution, whereas lack of effort is con- Attributions and Age and

a related study, Barnhill and Myles (2000) sidered an internal, unstable, probably Social Attributions and 10

found that 11 of the same 33 adolescents more specific, and controllable attribu- Results indicated that age was not related

with Asperger syndrome demonstrated a tion (Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, to social attributional style in this sample

general attributional style for positive 1978). Researchers (e.g., Dweck, 1975; of adolescents. It is possible that a rela-

events considered suggestive of a very Tollefson, 1982; Tollefson et al., 1982) tionship between age and attributional

pessimistic, failure-prone style even found that when students were in- style was not found in this study because

though 46% of these participants rated structed to attribute academic failure to of one or more of the following:

their depressive symptoms within the av- lack of effort, a personal characteristic

erage range and 9% in the above-average they could change, rather than to ability, (a) the small sample size,

range when compared to peers. Perhaps which they could not change, they con- (b) psychometric properties of the attri-

a cognitive training approach combined tinued to maintain expectations for suc- bution measure,

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on November 30, 2014

51

(c) possible confounding effects of might be involved in ability and effort During the time the teacher is manip-

medication, or rationales for social outcomes. Further- ulating the environment to foster posi-

(d) the fact that the age range of 12-1 more, it is possible that more intelligent tive social interactions, attribution retrain-

to 17-7 was relatively small. individuals with Asperger syndrome are ing may also be implemented. Research

developing that social life

an awareness in the area of academic attributions (e.g.,

Another reason may be that these differ- events are not just random or due to luck Dweck, 1975) has demonstrated that

ences cannot be detected until later in but may be caused by other factors, such children with learning disabilities who

life, such as in young adulthood. Future as mutual interest in a shared activity. experience success-only conditions show

research in this area is crucial given the However, it may be harder for these in- a deterioration in performance after fail-

clinical accounts of adults who were not dividuals to understand the impact of ure, whereas children in attribution re-

diagnosed with Asperger syndrome until their ability or effort on social success. training maintained improved their

or

after they had made a suicide attempt and This hypothesis is based on research performance. Adding attribution retrain-

the clinician had conducted a thorough indicating that persons with Asperger ing to the provision of successful social

developmental interview that revealed an syndrome experience varied degrees of experiences may be a successful interven-

undiagnosed developmental disability ability to empathize with others and tion strategy for individuals with As-

(Tantam, 1991). Recognizing the social understand their feelings (Ozonoff,

own perger syndrome.

attributional patterns of these individuals Rogers, Pennington, 1991). The more

& It would seem plausible that attribu-

might have led to interventions that intelligent individuals may realize that tion retraining should involve teaching

could have averted a serious crisis such as the external factors of chance and task students to change their expectations from

a suicide attempt. Therefore, the sooner difficulty do not determine their social uncontrollability to controllability, as

educational and medical professionals success, but they may not be aware of Abramson and colleagues (1978) recom-

can identify the individual’s social attri- how their ability or effort could affect mended. Teaching students specific so-

butional style, the quicker interventions their social success. If this is true, educa- cial skills not in their repertoires, teach-

can be implemented to assist the individ- tors might want to teach adolescents ing them self-reinforcement skills, and

ual in developing a more adaptive social with Asperger syndrome that crediting instructing them on how to find em-

attributional style. social success to an internal attribution, ployment are examples of ways to foster

Results revealed that IQ was nega- such as effort, might help them feel they a sense of control over outcomes. More-

tively related to overall social success at- have more control over life events and over, as mentioned earlier, Bandura’s

tributions (sum of ability, effort, chance, can affect social outcomes. (1982) assertion that people’s attribu-

and task factors) and to external factors tions mediate their behavior by deter-

for success, specifically chance and task mining what action they take and how

Implications for Practitioners

causes. In other words, the higher the much effort or persistence they exert ap-

IQ, the less the participants attributed It has been suggested that educators fos- pears to support these suggestions.

social success to the difficulty of the ter success situations in which students In addition, several strategies sug-

social task and to chance factors. Con- with Asperger syndrome can demon- gested by Williams ( 199 5 ) directed at ad-

versely, the lower the IQ, the more they strate their areas of strength while work- dressing several of the characteristics

attributed social success to the difficulty ing in cooperative learning situations typical of individuals with Asperger syn-

of the social task and to chance factors. with peers (Williams, 1995). For exam- drome, such as poor concentration, in-

However, a significant positive relation- ple, during reading time an individual sistence on sameness, restricted range of

ship between internal causes for success who is proficient in decoding can be interests, social impairment, and emo-

(ability and effort) and IQ level was not placed in a cooperative learning group tional vulnerability, are recommended to

found, which might have been expected where he or she will have the opportu- assist the individual in persisting at social

given the significant negative relation- nity to gain peer acceptance by classmates tasks perceived to be difficult. For exam-

ship found between external factors and viewing this skill as an asset to the group. ple, providing a significant amount of

success. At the same time, the teacher can edu- external structure and a predictable, safe

These findings may indicate that the cate the classroom peers about the im- classroom environment, minimizing tran-

more intelligent the adolescent, the more portance of modeling appropriate social sitions, and avoiding surprises may help

he or she recognizes that chance and task behavior for the individual with Asperger the student be more socially appropriate

conditions are not important factors in syndrome as well as teach them how to in school. Direct social skills training on

determining success in social situations. positively reinforce this individual’s at- the rules that others pick up intuitively

An attribution to luck or chance appears tempts at appropriate social interaction. but individuals with Asperger syndrome

to be a more concrete or simplistic ratio- The desired goal is for more peer accep- do not and protecting the child from bul-

nale and may not require the more ab- tance and an increase in prosocial behavior lying are intervention strategies to ad-

stract thought or social interaction that by the student with Asperger syndrome. dress social skills impairments and foster

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on November 30, 2014

52

appropriate social relationships. To in- .

ing variable in the present study is not adolescents receiving counseling or

were

crease the adolescent’s level of motiva- .

known. However, given the high inci- psychotherapy. However, the type of

tion and social task persistence, the teacher .

dence of depression in adolescents with counseling or therapy was not reported.

could incorporate in social skills lessons; Asperger syndrome (e.g., Ghaziuddin Future research efforts are needed to de-

the individual’s perseverative interest. . et al., 1998), it may be difficult to locate termine the best combination of inter-

Furthermore, the teacher needs to be: a sufficiently large sample of individuals ventions for these individuals given the

aware that students with Asperger syn- .

with Asperger syndrome who are not seriousness of the depression and re-

drome most often will not acknowledge; being treated with medication. ported suicide attempts in this popula-

that they are sad or depressed, because: Indeed, a clearer understanding of de- tion (Ghaziuddin et al., 1998; Tantam,

they are typically unaware of their feel- .

pression and how it is manifested in these 1991; Wolff, 1995). Finally, research is

ings. It is not sufficient to accept their .

individuals is desperately needed. It is needed to determine the impact of attri-

comments that they are okay. Therefore, , possible that children and adolescents bution retraining on individuals with As-

teachers must be vigilant to changes inL with Asperger syndrome are experienc- perger yndrome so that effective preven-

behavior that may indicate depression. , ing a significant unrecognized depression tive strategies can be implemented.

such as greater levels of disorganization, , that renders them unable to think about

inattentiveness, and isolation, a decreased . others or empathize with them. This in- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

stress threshold, excessive fatigue, crying, , ability to put oneself in another person’s Gena P. Barnhill, PhD, is a nationally certi-

and suicidal remarks, and report these to~ shoes has been attributed to theory of

the parents and mental health profes- mind deficits (Hurlburt, Happe, & Frith,

fied school psychologist and is currently working

as a consultant for the Autism/Asperger Syn-

sional (Williams, 1995). 1994); however, this lack of empathy and drome Resource Center in Kansas City, Kan-

All persons involved in the adoles- perspective may also be due to undiag- sas, and as an adjunct professor in the Depart-

cent’s life, including parents, educational . nosed depression. It is also not known ment of Special Education at the University of

staff, and outside agency professionals,1 ,

how the use of medication or other Kansas. Her current research interests include

need to be working on the same goals assessment and interventions for individuals

,

strategies such as diet and exercise affect

and implementing and reinforcing the. with Asperger syndrome. She is the mother of a

depression and attributions. Further re-

same strategies. For example, the attribu- search focusing on these strategies may 24-year-old son with Asperger syndrome. Ad-

tion retraining techniques implemented shed light on the relationship between dress: Gena P. Barnhill, Autism/Asperger Syn-

drome Resource Center, University of Kansas

by the private psychologist or social worker .

attributions and depression in individuals

Medical Center, 4001 HC Miller Building,

need to be reinforced by the school team with Asperger syndrome. In addition, the

3901 Rainbow Blvd., Kansas City, KS

and parents. It is suggested that the .

use of self-report instruments to assess

66160-7335.

school team have a qualified professional, ,

depression in individuals with Asperger

such as the school psychologist or coun- syndrome needs to be investigated more REFERENCES

selor, take the lead in providing attribu- thoroughly. To date, there is no research

tion retraining and in consulting with specifically addressing the issue of self- Abramson, L. Y., Seligman, M. E P., & Teas-

any private professionals as well as the report measures, and yet clinically it is re- dale, J. D. (1978). Learned helplessness in

school team and family regarding the in- humans: Critique and reformulation. Jour-

ported that individuals with Asperger nal of Abnormal Psychology, 87, 49-74.

tervention strategies in order to provide syndrome experience difficulty under- American Psychiatric Association. (1994).

a comprehensive and consistent educa- standing their feelings and emotions

tional program. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental

(Attwood, 1998). Investigating how de- disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Au-

pression is manifested at different devel- thor.

opmental ages in these individuals is an- Asperger, H. (1944). Die Autistischen Psy-

Need for Further Research other area for future research endeavors. chopathen im Kindesalter. Archiv fur Psy-

Furthermore, future research is needed chiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten, 117, 76-

Further research is needed to determine to determine if individuals with Asperger 136.

if these findings hold true for other sam- syndrome become depressed after real- Attwood, T. (1998). Asperger’s syndrome: A

ples of individuals with Asperger syn- life negative events as opposed to hypo- guide for parents and professionals. Philadel-

drome. Moreover, a larger sample size thetical events. Other researchers may phia, PA: Jessica Kingsley.

might allow for statistical analysis com- want to investigate the type of psy- Aydin, G. (1988). The remediation of chil-

dren’s helpless explanatory style and related

paring boys and girls. In addition, a chotherapy approaches persons with As- unpopularity. Cognitive Therapy and Re-

larger sample might yield more individu- perger syndrome are receiving as well as search, 12, 155-165.

als who are not on antidepressant med- the effectiveness of these different ap-

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy: Toward a

ications and thus allow for a comparison proaches in order to determine the best unifying theory of behavioral change. Psy-

between individuals with depression and psychotherapeutic method for these in- chological Review, 84, 191-215.

without depression. The degree to which dividuals. Parents of 36% of the partici- Barnhill, G., & Myles, B. S. (2000). Attribu-

medication may have been a confound- pants in this study reported that their tional style and depression in adolescents with

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on November 30, 2014

53

Asperger syndrome. Manuscript submitted nal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 23, 597- that predisposes those afflicted to adoles-

for publication. 606. cent and adult depression and suicide risk.

Bell, S. M., & McCallum, R. S. (1995). De- Hardan, A., & Sahl, R. (1999). Suicidal be- Journal of Learning Disabilities, 22, 169-

velopment of a scale measuring student havior in children and adolescents with de- 175.

attributions and its relationship to self- velopmental disorders. Research in Develop- Seligman, M. E. P., Peterson, C., Kaslow,

concept and social functioning. School Psy- mental Disabilities, 20, 287-296. N. J., Tanenbaum, R. L., Alloy, L. B., &

chology Review, 24, 271-286. Hurlburt, R. T., Happe, F., & Frith, U. (1994). Abramson, L. (1984). Attributional style

Burns, M. O., & Seligman, M. E. P. (1989). Sampling the form of inner experience in and depressive symptoms among children.

Explanatory style across the life span: Evi- three adults with Asperger syndrome. Psy- Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 93, 235-

dence for stability over 52 years. Journal of chological Medicine, 24, 385-395. 238.

Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 471- Kovacs, M. (1992). Children’s Depression In- Szatmari, P. (1991). Asperger’s syndrome:

477. ventory. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi- Diagnosis, treatment, and outcome. Psy-

Health Systems. chiatric Clinics of North America, 14(1),

DeMoss, K., Milich, R., & DeMers, S. (1993).

Marsh, H. W., Cairns, L., Relich, J., Barnes, 81-92.

Gender, creativity, depression, and attribu-

tional style in adolescents with high aca- J., & Debus, R. L. (1984). The relationship Tantam, D. (1991). Asperger syndrome in

between dimensions of self-attribution and adulthood. In U. Frith (Ed.), Autism and

demic achievement. Journal of Abnormal

Child Psychology, 21, 455-467.

dimensions of self-concept. Journal of Edu- Asperger syndrome (pp. 147-183). New

cational Psychology, 76, 3-32. York: Cambridge University Press.

DeRubeis, R J., & Hollon, S. D. (1995). Ex-

Myles, B. S., & Simpson, R. L. (1998). As- Tollefson, N. (1982). Parental strategies for

planatory style in the treatment of depres-

sion. In G. McClellan Buchanan & M.E.P. perger syndrome: A guide for educators and reducing learned helpless behavior among

parents. Austin, TX: PRO-ED. LD students. Paper presented at the annual

Seligman (Eds.), Explanatory style (pp. 99- Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Girgus, J. S., & Selig- meeting of the American Psychological As-

111). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. man, M. E. P. (1986). Learned helplessness sociation, Washington, DC. (ERIC Docu-

Dweck, C. S. (1975). The role of expectations in children: A longitudinal study of depres- ment Reproduction Service No. ED 226

and attributions in the alleviation of learned

sion, achievement, and explanatory style. 547)

helplessness. Journal of Personality and So- Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Tollefson, N., Tracy, D. B., Johnsen, E. P.,

cial Psychology, 31, 674-685.

51, 435-442. Buenning, M., Farmer, A., & Barke, C. R.

Frith, U. (1991). Asperger and his syndrome. Ozonoff, S., Rogers, S. J., & Pennington, (1982). Attribution patterns of learning

In U. Frith(Ed.), Autism and Asperger syn- B. F. (1991). Asperger’s syndrome: Evi- disabled adolescents. Learning Disability

drome (pp. 1-36). Cambridge, UK: Cam- dence of an empirical distinction from high- 5, 14-20.

Quarterly,

bridge University Press. functioning autism. Journal of Child Psy- Williams, K. (1995). Understanding the stu-

Ghaziuddin, M., Weidmer-Mikhail, & Ghaz- chology and Psychiatry, 32, 1107-1122. dent with Asperger’s syndrome: Guidelines

iuddin, N. (1998). Comorbidity of Asper- Robinson, P., & Trower, P. (1988). Social for teachers. Focus on Autistic Behavior,

ger syndrome: A preliminary report. Jour- skills training. In G. M. Breakwell, H. Foot, 10(2), 9-16.

nal of Intellectual Disability Research, 42, & R. Gilmour (Eds.), Doing social psychol- Wing, L. (1981). Asperger’s syndrome: A

279-283. ogy (pp. 172-184). New York: Cambridge clinical account. Psychological Medicine, 11,

Gladstone, T. R., & Kaslow, N. J. (1995). De- University Press. 115-129.

pression and attributions in children and Rourke, B. P., Young, G. C., & Leenaars, A. Wolff, S. (1995). Loners: The life path of un-

adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Jour- A. (1989). A childhood learning disability usual children. London: Routledge.

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on November 30, 2014

You might also like

- Interventions for Autism Spectrum Disorders: Translating Science into PracticeFrom EverandInterventions for Autism Spectrum Disorders: Translating Science into PracticeNo ratings yet

- Responses To The Negative Emotions of Others by Autistic, Mentally Retarded, and Normal ChildrenDocument13 pagesResponses To The Negative Emotions of Others by Autistic, Mentally Retarded, and Normal ChildrenBIANA-MARIA MACOVEINo ratings yet

- Aspergers - Educational InterventionsDocument7 pagesAspergers - Educational Interventionsroedershaffer100% (2)

- Asperger's Syndrome in Gifted Individuals: Gifted Child Today July 2001Document9 pagesAsperger's Syndrome in Gifted Individuals: Gifted Child Today July 2001Emanuele GuadagnoNo ratings yet

- Wing 1981 AspergerDocument15 pagesWing 1981 Asperger__aguNo ratings yet

- Asperger Syndrome Grows UpDocument37 pagesAsperger Syndrome Grows UpWilly Fonseca Vargas100% (1)

- Bacon1998 Article TheResponsesOfAutisticChildrenDocument14 pagesBacon1998 Article TheResponsesOfAutisticChildrenMaithri SivaramanNo ratings yet

- Modelo Basado en Fortalezas en El Autismo Winter-Messiers 2007Document13 pagesModelo Basado en Fortalezas en El Autismo Winter-Messiers 2007Valpe PsicólogosNo ratings yet

- Asperger Syndrome From Childhood Into AdulthoodDocument11 pagesAsperger Syndrome From Childhood Into AdulthoodAnimalHospitalNo ratings yet

- Shyness CrozierDocument4 pagesShyness Crozierkenneth0% (1)

- Asperger's Syndrome A Clinical Account. - tcm339-166245 - tcm339-284-32Document16 pagesAsperger's Syndrome A Clinical Account. - tcm339-166245 - tcm339-284-32andrei crisnic100% (1)

- Howlin 2003Document18 pagesHowlin 2003Alexandra AddaNo ratings yet

- Asperger Syndrome in ChildrenDocument8 pagesAsperger Syndrome in Childrenmaria_kazaNo ratings yet

- Particularităţi Ale Procesării Auditive În Contextul Tulburărilor Din Spectrul AutistDocument11 pagesParticularităţi Ale Procesării Auditive În Contextul Tulburărilor Din Spectrul AutistRamona Si CatalinNo ratings yet

- Mmpi 2 AutismDocument10 pagesMmpi 2 AutismvictorpsycheNo ratings yet

- Loneliness Effects On PersonalityDocument14 pagesLoneliness Effects On Personalityatikah nuzuliNo ratings yet

- Autism: Asperger Syndrome The Prevalence of Anxiety and Mood Problems Among Children With Autism andDocument17 pagesAutism: Asperger Syndrome The Prevalence of Anxiety and Mood Problems Among Children With Autism andDiana Petronela AbabeiNo ratings yet

- Facial Emotion Expression Recognition by Children at Familial Risk For DepressionDocument11 pagesFacial Emotion Expression Recognition by Children at Familial Risk For DepressionHuda ZainiNo ratings yet

- Blood Blood 2019 Bullying in Adolescents Who Stutter Communicative Competence and Self EsteemDocument11 pagesBlood Blood 2019 Bullying in Adolescents Who Stutter Communicative Competence and Self Esteemszabin.gereNo ratings yet

- Syndrome Asperger: February 2015Document8 pagesSyndrome Asperger: February 2015Gibson LieNo ratings yet

- StigmaDocument18 pagesStigmaStefana MariaNo ratings yet

- Stigmatising Feelings and Disclosure Apprehension Among Children With EpilepsyDocument5 pagesStigmatising Feelings and Disclosure Apprehension Among Children With Epilepsyanna regarNo ratings yet

- Sample Research Paper On Down SyndromeDocument5 pagesSample Research Paper On Down Syndromegmannevnd100% (1)

- Psychology For Exceptional Children Lesson 2Document5 pagesPsychology For Exceptional Children Lesson 2helienamarionsaliNo ratings yet

- Dissociative Identity Disorder: A Literature Review: Undergraduate Journal of PsychologyDocument6 pagesDissociative Identity Disorder: A Literature Review: Undergraduate Journal of PsychologyGerry AntoniNo ratings yet

- Emotion Knowledge As A Predictor of Social Behavior and Academic Competence in Children at RiskDocument6 pagesEmotion Knowledge As A Predictor of Social Behavior and Academic Competence in Children at RiskFabiana MartinsNo ratings yet

- Living With AutismDocument115 pagesLiving With Autismjjrelucio3748No ratings yet

- GENSLER - 2012 - Autism Spectrum Disorder in DSM-VDocument11 pagesGENSLER - 2012 - Autism Spectrum Disorder in DSM-VLoratadinaNo ratings yet

- Downs Syndrome Research PaperDocument7 pagesDowns Syndrome Research Paperapi-224952015No ratings yet

- 5.3clasgeom TXTDocument2 pages5.3clasgeom TXTMike-201No ratings yet

- Understanding and RecognisingDocument25 pagesUnderstanding and RecognisingJaviera ZepedaNo ratings yet

- Scattone2006 PDFDocument13 pagesScattone2006 PDFWanessa AndradeNo ratings yet

- Acquisition of Social Referencing Via Discrimination Training in InfantsDocument14 pagesAcquisition of Social Referencing Via Discrimination Training in Infantseric zampieriNo ratings yet

- Migration and Social DisruptionDocument15 pagesMigration and Social DisruptionALLNo ratings yet

- Project Muse 634841Document11 pagesProject Muse 634841MV FranNo ratings yet

- Strategii Pentru Copii Cu AspergerDocument16 pagesStrategii Pentru Copii Cu AspergerAna PostolacheNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0197455608000622 Main PDFDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0197455608000622 Main PDFBusu AndreeaNo ratings yet

- ED495689Document23 pagesED495689Mutiara AnnisaNo ratings yet

- Asperger SyndromeDocument8 pagesAsperger Syndromeflara putraNo ratings yet

- Robertson 1999Document8 pagesRobertson 1999Wanessa AndradeNo ratings yet

- 10.4324 9781315416175-39 ChapterpdfDocument5 pages10.4324 9781315416175-39 ChapterpdfRachel SawhNo ratings yet

- Syndrome Asperger: February 2015Document8 pagesSyndrome Asperger: February 2015Dena Paramita RustandiNo ratings yet

- Depressive Symptoms and Self-Concept in Young People With Spina BifidaDocument16 pagesDepressive Symptoms and Self-Concept in Young People With Spina BifidaHabibi AnggaraNo ratings yet

- Rogers 2003Document12 pagesRogers 2003dimasprastiiaNo ratings yet

- Kalo EmpiricalDocument28 pagesKalo EmpiricalchysaNo ratings yet

- Stigma of Mental Illness and Ways of Diminishing ItDocument9 pagesStigma of Mental Illness and Ways of Diminishing ItcaveolemuresNo ratings yet

- 2012 Article 85Document14 pages2012 Article 85KNo ratings yet

- Szatmari1995asperger, AutyzmDocument10 pagesSzatmari1995asperger, Autyzm__aguNo ratings yet

- Understanding Autism: Insights From Mind and Brain: Elisabeth L. Hill and Uta FrithDocument9 pagesUnderstanding Autism: Insights From Mind and Brain: Elisabeth L. Hill and Uta FrithAcademia das CriançasNo ratings yet

- Social Exclusion Amongst Adolescent Girls Their Self Esteem and Coping StrategiesDocument8 pagesSocial Exclusion Amongst Adolescent Girls Their Self Esteem and Coping StrategiesRoxana ElenaNo ratings yet

- DiscoDocument19 pagesDiscovcuadrosvNo ratings yet

- PEER - Stage2 - 10.1007/s00787 008 0701 0Document11 pagesPEER - Stage2 - 10.1007/s00787 008 0701 0Claire ClariceNo ratings yet

- The Risk of Social Interaction Problems Among Adolescents With ADHDDocument15 pagesThe Risk of Social Interaction Problems Among Adolescents With ADHDAnonymous 09S4yJkNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument23 pagesResearch Paperapi-644177877No ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis of Asperger Syndrome: Michael Fitzgerald & Aiden CorvinDocument9 pagesDiagnosis and Differential Diagnosis of Asperger Syndrome: Michael Fitzgerald & Aiden CorvinpipejaramilloNo ratings yet

- 1944-7558-116 1 3 PDFDocument14 pages1944-7558-116 1 3 PDFWahyu Agung CiptadiNo ratings yet

- The Reasons of Adult ShynessDocument12 pagesThe Reasons of Adult ShynesssyzwniNo ratings yet

- StokesDocument18 pagesStokesMarina ReisNo ratings yet

- Reports 313Document7 pagesReports 313Ilma Kurnia SariNo ratings yet

- He As OnDocument18 pagesHe As OniolandaszaboNo ratings yet

- Attitude of EMPLOYEES in Terms of Compliance of Health and SafetyDocument6 pagesAttitude of EMPLOYEES in Terms of Compliance of Health and SafetyJanice KimNo ratings yet

- The Dandenong Dossier 2010Document243 pagesThe Dandenong Dossier 2010reshminNo ratings yet

- PDP2 Heart Healthy LP TDocument24 pagesPDP2 Heart Healthy LP TTisi JhaNo ratings yet

- Preparing A Family For Childbirth and ParentingDocument5 pagesPreparing A Family For Childbirth and ParentingBern NerquitNo ratings yet

- SM Project 1Document75 pagesSM Project 1reena Mahadik100% (1)

- Therapy Is For Everybody: Black Mental HealthDocument22 pagesTherapy Is For Everybody: Black Mental HealthIresha Picot100% (2)

- WONCA2013 - Book of Abstracts PDFDocument830 pagesWONCA2013 - Book of Abstracts PDFBruno ZanchettaNo ratings yet

- The Miracle of ChocolateDocument10 pagesThe Miracle of ChocolateAmanda YasminNo ratings yet

- Nexus Magazine AprilMay 2019Document100 pagesNexus Magazine AprilMay 2019Izzy100% (2)

- Social Work MaterialDocument214 pagesSocial Work MaterialBala Tvn100% (2)

- Effective Leadership Towards The Star Rating Evaluation of Malaysian Seni Gayung Fatani Malaysia Organization PSGFMDocument10 pagesEffective Leadership Towards The Star Rating Evaluation of Malaysian Seni Gayung Fatani Malaysia Organization PSGFMabishekj274No ratings yet

- Homoeopathic Drug Proving: Randomised Double Blind Placebo Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesHomoeopathic Drug Proving: Randomised Double Blind Placebo Controlled TrialParag SharmaNo ratings yet

- Material Safety Data Sheet: 1 Identification of SubstanceDocument5 pagesMaterial Safety Data Sheet: 1 Identification of SubstanceRey AgustinNo ratings yet

- Tumors of Head and Neck RegionDocument94 pagesTumors of Head and Neck Regionpoornima vNo ratings yet

- Open Your Mind To Receive by Catherine Ponder Success Manual Edition 2010 PDFDocument34 pagesOpen Your Mind To Receive by Catherine Ponder Success Manual Edition 2010 PDFjose100% (2)

- AICTE CorporateBestPracticesDocument13 pagesAICTE CorporateBestPracticesramar MNo ratings yet

- ACSM - 2007 SpringDocument7 pagesACSM - 2007 SpringTeo SuciuNo ratings yet

- Uganda Dental Association Journal November 2019Document36 pagesUganda Dental Association Journal November 2019Trevor T KwagalaNo ratings yet

- Endo Gia Curved Tip Reload With Tri StapleDocument4 pagesEndo Gia Curved Tip Reload With Tri StapleAntiGeekNo ratings yet

- Valsalyacare Withprocuts....Document7 pagesValsalyacare Withprocuts....saumya.bsphcl.prosixNo ratings yet

- Hypo - RT PC TrialDocument37 pagesHypo - RT PC TrialnitinNo ratings yet

- Maslow TheoryDocument10 pagesMaslow Theoryraza20100% (1)

- Inc Tnai IcnDocument7 pagesInc Tnai IcnDeena MelvinNo ratings yet

- LA Low Cost Dog NeuteringDocument2 pagesLA Low Cost Dog Neuteringtonys71No ratings yet

- Playlist AssignmentDocument7 pagesPlaylist AssignmentTimothy Matthew JohnstoneNo ratings yet

- Advanced German Volume Training - Week 1Document9 pagesAdvanced German Volume Training - Week 1tactoucNo ratings yet

- Part-IDocument507 pagesPart-INaan SivananthamNo ratings yet

- Working in A Lab Risk & AssessmentDocument10 pagesWorking in A Lab Risk & AssessmentMariam KhanNo ratings yet

- Basic Word Structure (MT)Document19 pagesBasic Word Structure (MT)leapphea932No ratings yet

- CSR Activities by TATADocument13 pagesCSR Activities by TATAMegha VaruNo ratings yet

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (24)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (80)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Summary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (8)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Summary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (169)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryFrom EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (44)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeFrom EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (253)

- Sleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningFrom EverandSleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Summary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- How to ADHD: The Ultimate Guide and Strategies for Productivity and Well-BeingFrom EverandHow to ADHD: The Ultimate Guide and Strategies for Productivity and Well-BeingNo ratings yet

- Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassFrom EverandTroubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (26)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (328)

- An Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyFrom EverandAn Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- 12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosFrom Everand12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (207)

- Self-Care for Autistic People: 100+ Ways to Recharge, De-Stress, and Unmask!From EverandSelf-Care for Autistic People: 100+ Ways to Recharge, De-Stress, and Unmask!Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlFrom EverandThe Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (58)

- Summary: How to Be an Adult in Relationships: The Five Keys to Mindful Loving by David Richo: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: How to Be an Adult in Relationships: The Five Keys to Mindful Loving by David Richo: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (11)