Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Remembering The Victims of Stalin's Great Terror - Carnegie Europe - Carnegie Endowment For International Peace

Remembering The Victims of Stalin's Great Terror - Carnegie Europe - Carnegie Endowment For International Peace

Uploaded by

Andrew van DykeOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Remembering The Victims of Stalin's Great Terror - Carnegie Europe - Carnegie Endowment For International Peace

Remembering The Victims of Stalin's Great Terror - Carnegie Europe - Carnegie Endowment For International Peace

Uploaded by

Andrew van DykeCopyright:

Available Formats

OUR NETWORK CONTACT

RESEARCH AREAS 5 PUBLICATIONS EXPERTS EVENTS 2 4

Judy Dempsey’s Strategic Europe

Home Issues Regions Series Archives RSS < H Search

4

Remembering the Victims of Stalin’s

Great Terror

JUDY DEMPSEY

An exhibition of Stalin’s campaign of political repression in

1937–1938 coincides with Vladimir Putin’s attempts to forget

this part of Russia’s past.

March 09, 2015 PRINT PAGE

W hen martial law was declared in Poland in December 1981,

Tomasz Kizny, then twenty-three years old, had the choice between

SUBSCRIBE TODAY

Sign up to receive Judy Dempsey’s

Strategic Europe updates in your inbox!

emigrating and joining the underground resistance.

Enter email address

SUBMIT

Kizny chose the second option. He became a member of the

Solidarity trade union movement and spent the rest of the decade

taking photos of a dogged resistance that was to bring the RECENT ANALYSIS FROM

JUDY DEMPSEY’S STRATEGIC EUROPE

Communist party to its knees. In 1989, the regime relinquished its

The EU’s Water Strategy Is Too

leading role when it joined roundtable talks with the opposition. It Shallow

Thursday, April 06, 2023

was an extraordinary time. Kizny seized the opportunity to capture

Europe’s Dangerous

the past on camera.

Dependence on China

Tuesday, April 04, 2023

“ALer 1989, I Mnally had the possibility to get a passport,” Kizny told

Judy Asks: Is Hungary a

Carnegie Europe on the eve of the opening of his exhibition, !e Reliable EU and NATO

Member?

Great Terror 1937–1938. Pe photographer’s commemoration of the Thursday, March 30, 2023

victims of Stalin’s political repression is now on show at the House of

Poland’s (Lack of) Vision for

Brandenburg-Prussian History in Potsdam, Germany. Europe

Tuesday, March 28, 2023

Instead of going West aLer

Putin and Xi Are Making the

the fall of Communism, Judy Dempsey War in Ukraine a Global

Dempsey is a nonresident Contest

Kizny went East to Vorkuta, senior fellow at Carnegie

Thursday, March 23, 2023

Europe and editor in chief of Strategic

a Russian town north of the Europe.

Arctic Circle. He had a <

@JUDY_DEMPSEY

reason. “I wanted to follow Judy Dempsey Retweeted

Tymofiy Mylo…

the traces of the Polish @Mylovanov · 22h

prisoners,” he explained. Replying to @Mylovanov

None of it would be possible

without the minister of health

Pere were two waves of Polish deportations under Stalin. Pe Mrst @liashko_viktor and the deputy

governor of the Kyiv regional

was in 1939, the second in 1944–1945. Kizny’s own grandparents and administration @TwinLawyer

They kept pushing us. Also, the

great-grandparents were caught up in the deportations, under which heart of the project was Bohdan B,

the deputy minister of health 5/

prisoners were sent to the Gulag forced-labor camps. Some never

returned.

Until the late 1980s, the Gulags had been taboo in Poland. Kizny had

read about them in samizdat, the Soviet-era system of clandestinely

printing and distributing censored literature. “It was in the late 1970s 1 219

when I read [Aleksandr] Solzhenitsyn’s !e Gulag Archipelago. It was Judy Dempsey Retweeted

circulating in samizdat. I had one and a half days to read it and then I

@Judy_Dempsey

had to pass it on. It had a huge impact on me,” he recalled.

RECENT ANALYSIS FROM

ALer he Mnished his project about Polish prisoners, Kizny turned his CARNEGIE EUROPE

Rethinking Democracy and

camera to the Gulags themselves. Pe opportunities to access archives Civil Society Support in Acute

Crises

and to travel throughout Russia were opened up. Tuesday, April 11, 2023

Under Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union’s last leader, and Boris Israel-Palestine’s Democracy

Yeltsin, Russia’s Mrst post-Communist president, the past became and Security Crisis: How Should

the EU Respond?

accessible. Pe Gulags, the Great Terror of 1937–1938, and the Katyn Wednesday, April 05, 2023

massacre—a series of mass executions of Poles carried out by the Ukraine’s Total Democratic

Soviet secret police in 1940—were no longer taboo. Resilience in the Shadow of

Russia’s War

Tuesday, April 04, 2023

“Pere was access to the archives,” Kizny recalled. “Pere was access

to the sites where the Gulags once were.” His book, which coincided Learning to Do No Harm to

Democracy in Engagement

with Anne Applebaum’s monumental Gulag: A History, was the Mrst With Authoritarian States

Wednesday, March 15, 2023

visual book about the labor camps.

After Russia’s War Against

Kizny then turned his attention to the Great Terror. For him, his Ukraine: What Kind of World

Order?

oLen-harrowing work on that subject was about preserving the Tuesday, February 28, 2023

memory of a horriMc episode of Russian history in which 750,000

people from all backgrounds were executed, secretly, between August

1937 and November 1938.

“One in 100 of the Soviet Union’s adult citizens were secretly

murdered. Pat’s 1,600 executions a day,” Kizny said. More than

800,000 were sentenced to up to ten years’ hard labor in the Gulag

camps. Only 100,000 survived.

Kizny’s photographs of the Great Terror are special in three ways. Pe

Mrst is the impact of the faces of those prisoners who were

photographed by the Soviet secret police when they were arrested. In

most cases, the prisoners were murdered within forty-eight hours.

In the exhibition, 79 black-and-white photos of these individuals

stare out at you. Most have an expression of bewilderment, fear, and

exhaustion. ALer 1938, the photos were stored in secret archives.

“When they came to light in the early 1990s, they became one of the

most vivid visual accounts of Soviet Communism’s crimes,” Kizny

said.

Pe second striking aspect of the exhibition is Kizny’s series of

pictures of places where there were mass graves. With assistance from

Memorial, an independent organization set up in the early 1990s to

investigate and preserve the memory of those persecuted in the Soviet

Union, Kizny found, visited, and photographed the sites.

His pictures convey a sense of emptiness, of silence, of the shocking

reminder that underneath Orthodox churches, forests, factories, and

hills are the remains of so many innocent people who were shot and

then thrown into mass graves.

Pe third and most moving aspect of the exhibition is the set of

photos and interviews Kizny held with the children of the victims. By

now, these are old, sad people. Looking straight into the camera, they

recount the past. Pey talk of the last time they saw their parents, of

being unable for years to Mnd out what happened to them, or to

discover why, where, and when they were executed—or where they

were buried.

“Pese children were deprived of mourning. Mourning is a part of the

human condition. For years and years they knew nothing,” Kizny

said. Yeltsin had rehabilitated many of those who died or survived the

camps. “Even then,” said Kizny, “when the survivors had been freed

from the camps, they were second-class citizens. In many cases, their

lives had been broken.”

Pe interviews, in Russian with German subtitles, have the effect of

transporting you back to a distant past dominated by fear,

helplessness, and being forgotten. Pey are very powerful and very

moving.

For Kizny and his colleagues and friends in Memorial, investigating,

preserving, and talking about the past is tied to a country’s identity—

and, indeed, its future. “Memory is so important for the identity of a

country. What happens to a nation without a memory, with a

selective view of the past?” Kizny asked rhetorically.

Under President Vladimir Putin, Russia’s past is under scrutiny but in

completely the opposite way to how Gorbachev and Yeltsin dealt with

it. Memorial, for example, has been under constant pressure from the

Kremlin, as are many other independent nongovernmental

organizations.

In early March 2015, Perm-36, the only museum in Russia created on

the site of a former Gulag camp, was forced to close. “It is ceasing its

activities and beginning the process of self-liquidation,” according to

a statement issued by the museum.

“It’s terrifying what is happening,” Kizny said. “It’s as if there are two

kinds of memories competing with each other—the positive and the

negative one. Pe historical policy of the Kremlin is about an identity

linked to a great state, not to the tragic things that Russians did to

Russians.”

Photo credit: Tomasz Kizny

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein

are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its

trustees.

More on: RUSSIA

RELATED ANALYSIS FROM CARNEGIE EUROPE

Rethinking Democracy The EU’s Water Strategy Israel-Palestine’s Europe’s Dangerous

and Civil Society Is Too Shallow Democracy and Security Dependence on China

Support in Acute Crises OLIVIA LAZARD Crisis: How Should the JUDY DEMPSEY

JAKOB HENSING EU Respond?

MELISSA LI

BETH OPPENHEIM

OUR NETWORK Contact By Email SUPPORT CARNEGIE

Carnegie Endowment for For Media In an increasingly crowded, chaotic,

International Peace J Employment and contested world and

Carnegie Europe marketplace of ideas, the Carnegie

J

Privacy Policy

Endowment offers decisionmakers

Carnegie India J

global, independent, and strategic

Carnegie Russia Eurasia J insight and innovative ideas that

Rue du Congrès, 15

Carnegie China advance international peace.

1000 Brussels, Belgium J

Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle

Phone: +32 2 735 56 50 Learn More J

East Center J

Fax: +32 2736 6222

FOLLOW US

© 2023 All Rights Reserved

G By using this website, you agree to our cookie policy.

You might also like

- Edgar Morin - The Cinema, or The Imaginary Man-University of Minnesota Press (2005)Document331 pagesEdgar Morin - The Cinema, or The Imaginary Man-University of Minnesota Press (2005)Sandra CoelhoNo ratings yet

- Hyperreality and Simulacra in Truman ShowDocument33 pagesHyperreality and Simulacra in Truman ShowM fadriansyah mahendra aasNo ratings yet

- Antonio Gramsci: A Pedagogy To Change The World: Nicola Pizzolato John D. Holst EditorsDocument239 pagesAntonio Gramsci: A Pedagogy To Change The World: Nicola Pizzolato John D. Holst EditorstottNo ratings yet

- Tabachnick-Of Maus and Memory 1993Document10 pagesTabachnick-Of Maus and Memory 1993A Guzmán MazaNo ratings yet

- The Lives of OthersDocument3 pagesThe Lives of OthersAjsaNo ratings yet

- Day 1 - Communism Vs Capitalism MaterialsDocument2 pagesDay 1 - Communism Vs Capitalism MaterialsJaredNo ratings yet

- The Cold War ReviewDocument25 pagesThe Cold War Reviewegermind90% (21)

- Politico 13-19 OctoberDocument28 pagesPolitico 13-19 OctobergwoscarNo ratings yet

- Newsletter No3Document26 pagesNewsletter No3danielNo ratings yet

- Postmodernism - Postmodernity 2023Document42 pagesPostmodernism - Postmodernity 2023carmelyagmurNo ratings yet

- Cold War and MoviesDocument4 pagesCold War and MoviesjeiddiNo ratings yet

- Interview Zygmunt Bauman "Social Media Are A Trap" in English EL PAÍS PDFDocument8 pagesInterview Zygmunt Bauman "Social Media Are A Trap" in English EL PAÍS PDFRaúl ZuraNo ratings yet

- Welcome To Wikipedia,: From Today's Featured Article in The NewsDocument3 pagesWelcome To Wikipedia,: From Today's Featured Article in The NewsbendyFrogNo ratings yet

- Biron - Birkbeck Institutional Research OnlineDocument8 pagesBiron - Birkbeck Institutional Research Online吴宇超No ratings yet

- I Fluxus, The Abolition of Art, The Soviet Union, and PureDocument15 pagesI Fluxus, The Abolition of Art, The Soviet Union, and PureEl Amigo SebastiánNo ratings yet

- OnCurating Issue25 Stassi DINA4Document6 pagesOnCurating Issue25 Stassi DINA4prosopopeia226No ratings yet

- Mapping Capitalism - Cognitive Mapping in Southland TalesDocument16 pagesMapping Capitalism - Cognitive Mapping in Southland TalesjustinpickardNo ratings yet

- Alert 18 Russia S Info WarDocument2 pagesAlert 18 Russia S Info Wardoncohones1987No ratings yet

- Running Head: Photo History. 1Document8 pagesRunning Head: Photo History. 1Stephen Banda KaseraNo ratings yet

- German Gothic SubcultureDocument17 pagesGerman Gothic SubculturenoularNo ratings yet

- On Dystopia: Terminator Sequence (1984-2009) To The Matrix Trilogy (1999-2003)Document16 pagesOn Dystopia: Terminator Sequence (1984-2009) To The Matrix Trilogy (1999-2003)api-215491864No ratings yet

- Keathley, Christian, Cinephilia and History, or The Wind in The TreesDocument233 pagesKeathley, Christian, Cinephilia and History, or The Wind in The TreesChris DingNo ratings yet

- Kurt Tucholsky, John Heartfield and Deutschland, Deutschland Über AllesDocument17 pagesKurt Tucholsky, John Heartfield and Deutschland, Deutschland Über AllesKamal KhouryNo ratings yet

- The Theatre of The AbsurdDocument16 pagesThe Theatre of The Absurdbal krishanNo ratings yet

- The Imaginary Other Spectator A Paradigm (2018!01!21 12-53-44 UTC)Document10 pagesThe Imaginary Other Spectator A Paradigm (2018!01!21 12-53-44 UTC)Caterina PostiNo ratings yet

- Cold War DocumentaryDocument4 pagesCold War DocumentaryKarla GaratachiaNo ratings yet

- "Address of The President of The United States, Recommendation For Assistance To Greece and Turkey" March 12, 1947Document3 pages"Address of The President of The United States, Recommendation For Assistance To Greece and Turkey" March 12, 1947BuggaLynNo ratings yet

- Cinematic Analysis: The Day The Earth Stood Still (1951) Part A: SummaryDocument5 pagesCinematic Analysis: The Day The Earth Stood Still (1951) Part A: Summaryjulianpcap2017No ratings yet

- BFI - SunriseDocument39 pagesBFI - Sunrisesteryx88100% (1)

- Assignment 1 TemplateDocument2 pagesAssignment 1 Templatefrancess gideonNo ratings yet

- Anglais: MP, PC, PsiDocument4 pagesAnglais: MP, PC, PsiyassineNo ratings yet

- 1982 - Modleski - Film Theory's DetourDocument8 pages1982 - Modleski - Film Theory's DetourdomlashNo ratings yet

- Pub - The Times Literary Supplement PDFDocument32 pagesPub - The Times Literary Supplement PDFlevy12No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument273 pagesUntitledLayke ZhangNo ratings yet

- Drowned in Eau de Vie: Modris EksteinsDocument4 pagesDrowned in Eau de Vie: Modris EksteinsAva LancheNo ratings yet

- Why I Wrote "The Crucible": An Artist's Answer To PoliticsDocument13 pagesWhy I Wrote "The Crucible": An Artist's Answer To PoliticsDiego BecerraNo ratings yet

- Cold War Flashcards - UpdatedDocument20 pagesCold War Flashcards - UpdatedZackNo ratings yet

- Catherine Russell Narrative MortalityDocument281 pagesCatherine Russell Narrative MortalitynataliNo ratings yet

- Totalitarianism On ScreenDocument275 pagesTotalitarianism On ScreenAnomerte100% (2)

- Howard Caygill - Black PanthersDocument7 pagesHoward Caygill - Black Panthers2dxyvgyqvxNo ratings yet

- Rejecting The American Model: Peter Kropotkin'S Radical CommunalismDocument27 pagesRejecting The American Model: Peter Kropotkin'S Radical CommunalismMLNo ratings yet

- 2015 09 29 JFKs Forgotten Crisis PDFDocument32 pages2015 09 29 JFKs Forgotten Crisis PDFImran Sajjad BhatNo ratings yet

- How To Watch A Documentary - Article and QuestionsDocument5 pagesHow To Watch A Documentary - Article and Questionsanushreepatel24No ratings yet

- Physics at The University of Stuttgart in West GermanyDocument3 pagesPhysics at The University of Stuttgart in West Germanyviwokec711No ratings yet

- 5 Taiwan's Cold War Geopolitics in Edward Yang's The TerrorizersDocument15 pages5 Taiwan's Cold War Geopolitics in Edward Yang's The TerrorizersBlue JoNo ratings yet

- Nostalgia MATRIX 230 by Leigh Markopoulos Art Practical-1283443850Document2 pagesNostalgia MATRIX 230 by Leigh Markopoulos Art Practical-1283443850Mini OvniNo ratings yet

- Why I Wrote "The Crucible": An Artist's Answer To PoliticsDocument11 pagesWhy I Wrote "The Crucible": An Artist's Answer To Politicsapi-529233582No ratings yet

- The Politics of Ostalgie - Post Socialism Nostalgia in Recent German Film - ENNS, ADocument17 pagesThe Politics of Ostalgie - Post Socialism Nostalgia in Recent German Film - ENNS, AVictóriaVórosNo ratings yet

- World at War 87Document84 pagesWorld at War 87Jose Ibanez100% (1)

- Tupitsyn 1999Document14 pagesTupitsyn 1999Miguel RamiresNo ratings yet

- What Matters: Photographs That Can Change The WorldDocument4 pagesWhat Matters: Photographs That Can Change The WorldViennalooiNo ratings yet

- Stuart Hall Et Al - Gramsci SupplementDocument9 pagesStuart Hall Et Al - Gramsci SupplementdNo ratings yet

- Furr Article About KatynDocument36 pagesFurr Article About KatynΣπύρος ΑNo ratings yet

- The Handmaids Tale 4Document241 pagesThe Handmaids Tale 4Christina HuNo ratings yet

- The Soviet Famine of 1932-1933 ReconsideredDocument14 pagesThe Soviet Famine of 1932-1933 ReconsideredpointlessNo ratings yet

- Sublimation: 6 Death in Venice and The Aesthetics ofDocument2 pagesSublimation: 6 Death in Venice and The Aesthetics ofLilly VarakliotiNo ratings yet

- Operation Mindfuck - The Origins of The Illuminati Conspiracy Fraud and How It Became Popular in Our TimesDocument69 pagesOperation Mindfuck - The Origins of The Illuminati Conspiracy Fraud and How It Became Popular in Our TimesPreston IsaacsonNo ratings yet

- Welcome To Wikipedia,: From Today's Featured Article in The NewsDocument4 pagesWelcome To Wikipedia,: From Today's Featured Article in The NewsR0b B0nis0l0No ratings yet

- Why I Wrote "The Crucible" - The New YorkerDocument13 pagesWhy I Wrote "The Crucible" - The New Yorkerdoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Modern World History-11Document76 pagesModern World History-11Yağmur TükelNo ratings yet

- Backdrop On Rizal's Time YAPISODocument66 pagesBackdrop On Rizal's Time YAPISOSyvel Jay Silvestre TortosaNo ratings yet

- Communist Manifesto Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesCommunist Manifesto Lesson Planapi-356387598No ratings yet

- Lily Tran - Assignment 1Document10 pagesLily Tran - Assignment 1api-551757696No ratings yet

- The Freedom Manifesto of The 21st CenturyDocument18 pagesThe Freedom Manifesto of The 21st CenturyXinyu Hu100% (1)

- Timeline of The Cold WarDocument5 pagesTimeline of The Cold Warapi-112856800No ratings yet

- KM 3Document4 pagesKM 3Ilham Binte AkhterNo ratings yet

- Grenada DocumentsDocument813 pagesGrenada DocumentsDon Manuel Saavedra P.100% (1)

- János Berecz RemembersDocument222 pagesJános Berecz RemembersHorváth BálintNo ratings yet

- Karl Marx Political SociologyDocument9 pagesKarl Marx Political SociologyTariq Rind100% (3)

- Social ResponsibilityDocument12 pagesSocial ResponsibilityJasmin VillamorNo ratings yet

- Era of StagnationDocument9 pagesEra of StagnationVivek SinghNo ratings yet

- DISS ExamDocument2 pagesDISS ExamAlexa Ianne Monique TuquibNo ratings yet

- Philippine Politics and Governance. NotesDocument9 pagesPhilippine Politics and Governance. NotesGretchen Barnayha LeeNo ratings yet

- Seven Myths About The USSR - What's LeftDocument15 pagesSeven Myths About The USSR - What's Leftstamatis122No ratings yet

- Secularism, Modernity, Nation - Epistemology of The Dalit CritiqueDocument14 pagesSecularism, Modernity, Nation - Epistemology of The Dalit CritiqueSam JoshvaNo ratings yet

- Nikita KhrushchevDocument45 pagesNikita KhrushchevBMikeNo ratings yet

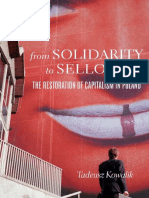

- 13 Kowalik, From Solidarity To Sellout PDFDocument367 pages13 Kowalik, From Solidarity To Sellout PDFporterszucsNo ratings yet

- Russian RevolutionDocument14 pagesRussian Revolutionadarsh_thombre_1No ratings yet

- Social Class and Class Struggle in Suzanne Collins S The Hunger Games PDFDocument9 pagesSocial Class and Class Struggle in Suzanne Collins S The Hunger Games PDFRazia KhanNo ratings yet

- Thesis: How The Inequality of Rousseau Differs From Marx's Conception of Inequality? and How TheDocument9 pagesThesis: How The Inequality of Rousseau Differs From Marx's Conception of Inequality? and How TheAbdel-badih ArissNo ratings yet

- Types of GovernmentDocument7 pagesTypes of GovernmentJscovitchNo ratings yet

- Socialism From Below - David McNallyDocument23 pagesSocialism From Below - David McNallyoptimismofthewillNo ratings yet

- Alexandra Kollontai and The Woman Question Women and Social Revolution, 1905-1917 - Caitlin VestDocument11 pagesAlexandra Kollontai and The Woman Question Women and Social Revolution, 1905-1917 - Caitlin VestsergevictorNo ratings yet

- Fall of Communism PowerpointDocument29 pagesFall of Communism PowerpointSanjana Gupta50% (2)

- Marxist Jurisprudence PDFDocument10 pagesMarxist Jurisprudence PDFPunam ChauhanNo ratings yet

- The Communist Party A Manual On OrganizationDocument132 pagesThe Communist Party A Manual On OrganizationJ.M.G.No ratings yet

- 1900-The Present Review Key Concept 6.1 Science and The EnvironmentDocument4 pages1900-The Present Review Key Concept 6.1 Science and The Environmentjkomtil7No ratings yet