Professional Documents

Culture Documents

L12 Externalities

Uploaded by

Rick DiazOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

L12 Externalities

Uploaded by

Rick DiazCopyright:

Available Formats

EC2066 MICROECONOMICS

TOPIC 12: EXTERNALITIES AND PUBLIC GOODS

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, and having completed the Essential readings and activities, you should

be able to:

Define positive and negative externalities, and explain how and why the presence of

externalities creates inefficient outcomes

Compute the socially efficient outcome, and the outcome in the presence of

externalities, and compare the two for standard problems

Show (both in theory and in exercises) how taxation, regulation, property rights and

licensing can overcome market failure in the presence of externalities

Define and give examples of public goods

Explain why competitive markets with public goods may not operate efficiently.

Essential Reading

Morgan, Katz and Rosen [MKR], Microeconomics, Chapter 18.

Perloff, J.M., Microeconomics: theory and applications with calculus. Chapter ?

Pindyck and Rubenfeld (PR) chapter

1. Preface

In the previous chapter on General Equilibrium, we learnt about Pareto efficiency,

production efficiency and consumption efficiency.

In this chapter, we are going to learn about the main factors of market incompleteness

or even market failure. These factors are externalities and public good.

2. Externalities

According to the subject guide, there is an externality if the actions of an agent

(consumer or firm) affect directly the welfare of another agent in a way that is not

captured by a price effect. This situation arises when there are goods that are non-

excludable.

Non-excludability implies that it is impossible to exclude other individuals from consuming

the good when one individual is consuming this good. Other individuals will either benefit

or suffer from it.

Copyright: Singapore Institute of Management Page |1

EC2066 MICROECONOMICS

In the chapter on General Equilibrium, we assumed that all goods are private goods

which are strictly for private consumption only and hence excludable. For example,

buying a cup of coffee in the canteen. In this chapter we are dealing with a non-excludable

good.

For example, you are watching Running Man in the lab and you cannot stop the lady

sitting behind you from watching it (benefit). Meanwhile, you do not use a headset and

the loud voice disturbs the nerd who is also sitting beside you (suffering).

The consumption of a non-excludable good triggers externality. There are two types of

externalities: negative externalities (detrimental) and positive externalities (beneficial).

With regards to the above example, there are positive externalities for the lady because

she enjoys the show, but there are negative externalities to the nerd because he suffers

from it.

3. Negative Externalities

Negative externalities happen if the action that the agent exerts decreases other agent’s

welfare (reduces consumers’ utility or generates an extra cost for other firms).

For example, consider a steel plant located at the upstream that pump out its waste into

the river. Then, it causes negative externalities to the fishermen downstream, as the

toxic waste pollutes the river and reduces the number of fish available to the fishermen.

Under such circumstance, we said that it is the steel producer affects the fishermen. It

also causes negative externalities to the public who enjoys swimming in the river too.

Therefore, the producer also affects the consumers.

We can use a supply and demand diagram for the steel market to show that under

perfect competition, steel plants produce excessive pollution because each firm’s private

cost is lesser than the social cost. Graphically,

Copyright: Singapore Institute of Management Page |2

EC2066 MICROECONOMICS

225

172.5

141 DW

120

15

Q

84 105 225

Assuming steel market demand, 225

Firms’ private marginal cost (marginal cost), 15

Firms’ pollution marginal cost (externalities),

Social marginal cost is the sum of two, 15

Firms will not factor the pollution into its cost consideration. It will produce at the

competitive equilibrium where → 225 15

At the competitive market equilibrium, 105, 120

The social optimum happens where → 225 15

At the social optimal point, 84, 141

The deadweight loss, 2,756.25

The steel plant over produce at 105 because the social optimum point happens at

84

4. Negative Externalities and Monopoly

Earlier, we assume that the steel plant is engaged in perfect competition. Now, let us

assume that the steel plant is a monopolist.

Copyright: Singapore Institute of Management Page |3

EC2066 MICROECONOMICS

225

DW

165

155

120

105

15

MR D

Q

60 70 84 225

Assuming steel market demand, 225

Marginal revenue of steel market demand, M 225 2

Firms’ private cost (marginal cost), 15

Firms’ pollution cost (externalities),

Social marginal cost, 15

Firms will produce at the monopolistic equilibrium where → 225 2

15

At the monopolistic market equilibrium, 70, 155

Suppose the monopolist takes the pollution cost into consideration, it will produce at

→ 225 2 15 , or, 60, 165

The deadweight loss when the monopolist produces at 60, 475

The deadweight loss when the monopolist produces at 70, 245

Notice that the DW loss due to negative externalities is smaller under monopoly than

perfect competition.

Copyright: Singapore Institute of Management Page |4

EC2066 MICROECONOMICS

5. Positive Externalities

Contrasted against negative externalities, positive externalities happen if the action that

the agent exerts increases another agent’s welfare (increases consumer utility or

generates an extra benefit for other firms).

For example, consider the effect of Christiano Ronaldo joining Real Madrid a few years

ago, which boosted the sales of merchandise at the club (like football jerseys with CR7

printed behind). Since Adidas was the shirt sponsor of Real Madrid, the increase in the

sales of football jerseys benefited Adidas too.

P

MC

225

195

157.5 DW

120

15

MPB MSB

Q

105 142.5 225

Notice that the market demand is also the marginal private benefit from consuming

the good. That is, the benefit from an additional unit of a good or service that the

consumer of that good or service receives.

Assuming CR7 jersey demand or marginal private benefit is, 225

Seeing someone wearing a CR7 jersey, fans of Christiano Ronaldo will also be happy.

This gives rise to Marginal External Benefit of consuming CR7 jerseys, i.e., the benefit

from an additional unit of the CR7 jersey that people other than the consumer enjoys.

Defining marginal social benefit (MSB) as the marginal benefit enjoyed by the entire

society, both by the consumer and by everyone else (MSB = MPB + Marginal External

Benefit).

Here, the marginal social benefit is, 300

Copyright: Singapore Institute of Management Page |5

EC2066 MICROECONOMICS

Firms’ private cost (marginal cost), 15

Firms produces at the competitive equilibrium where → 225 15

At the competitive market equilibrium, 105, 120

When firms produce 105, the corresponding price under MSB is 195.

The social optimum happens where → 300 15

At the social optimal point, 142.5, 157.5

The deadweight loss is thus, 1406.25

Real Madrid under-produces the CR7 jersey at 105 because the social optimum

happens at 142.5

6. How to Overcome Externalities

Mergers

In the case of negative externalities, the root of the problem is that the firm produces

according to its private marginal cost instead of social cost. In the case of positive

externalities, the problem is caused by the firm producing according to its private

marginal benefit instead of social marginal benefit.

Merger is a good solution to the externality problem as it internalises the problem by

combining the involved parties and aligning their interests.

For example, in the positive externalities case, if Real Madrid and Adidas merge, then

their combined interest will be the social marginal benefit. Therefore, Real Madrid will

produce at the social optimum level to maximise their combined profit.

In the case of the steel plant and fishermen, suppose the two merge, the steel plant will

consider the suffering of fishermen when it pollutes. Knowing that pollution will increase

the fishermen’s cost, the steel plant might reduce production if it operates in a

competitive environment.

Taxes

In the case of negative externalities with perfect competition, it is possible to force the

steel plant to produce at the social optimum level of output by imposing a per unit tax on

it.

Copyright: Singapore Institute of Management Page |6

EC2066 MICROECONOMICS

225

172.5

141

120

15

Q

84 105 225

At the social optimum level of output, the steel plant produces at → 141

15 84 , which implies 42.

Emissions standards

The government can also set emission standards to limit the waste pollution from the

steel plant. In order to fulfil the emission standards, the steel plant needs to reduce its

production output and thus, the corresponding water pollution.

Coase Theorem

Another core issue of externalities lie in the lack of ownership of the resources, which

leads to inefficiency.

According to Coase Theorem, if property rights exist, if only a small number of parties

are involved, and transactions costs are low (or zero), then private transactions are

efficient.

Coase Theorem implies that, regardless to whom the property right is given (the polluter

or the victim), as long as a property right is granted, an efficient level of pollution results.

Using the steel plant example, if the fishermen are assigned the ownership of the river,

then the fishermen have the right to demand compensation from the steel plant polluting

the river and affecting their livelihood. Therefore, the steel plant has to either cut down

production or install environmentally-friendly machinery/processes.

Copyright: Singapore Institute of Management Page |7

EC2066 MICROECONOMICS

If the steel plant is assigned the ownership of the river, then when the fishermen

complain, the steel plant will point out that it has the right to pollute the river. So, the

fishermen might have to install a water purification plant to clean up the polluted river.

After cleaning the river, the efficient level of pollution will result.

As long as the ownership of the resources is assigned to either party, the problem of

externalities might be solved, depending which party bear the cost. Whether the steel

plant install the environmentally-friendly machinery or if the fishermen build a water plant.

However, there are some special cases where negative externalities cannot be solved

although there is ownership of the resources. For example, when there are too many

steel plants upstream, it is very hard to identify which plant pollutes more and which

plant needs to install environmentally-friendly machinery. Or when there are too many

fishermen downstream, and none of them are willing to bear the cost of building the

water plant, which will benefit everyone else.

7. Public Good

Public good is a product that one individual can consume without reducing its availability

to another individual and from which no one is excluded.

Public goods give positive externalities such as the water purification plant in the above

example. The water purification plant will benefit every fisherman downstream of the

river, whether or not they contribute to the building of the water plant. Other examples

are public defence, public parks, street lights and the police force.

The characteristics that differentiate a public good from a private good are:

- Non-excludable: Once the good has been produced, everyone in the market cannot

be excluded from using and benefiting from the good.

- Non-rivalry: the extra consumption of the public good by one extra person doesn’t

reduce the benefits of the rest who consumes that particular public good.

The table below demonstrates the possible characteristic of a public good with different

kinds of combination of non-excludability and non-rivalry.

Exclusion Non-Exclusion

Rivalry Private good like chocolate Open access common property

like fishery, hunting

Non-rivalry Private good with exclusion Public good without exclusion like

like cable TV national defence, clean air.

Copyright: Singapore Institute of Management Page |8

EC2066 MICROECONOMICS

8. Free Riding and Public Goods

Normally, under the presence of free-riding and private consumption, the provision of

public goods are likely to be under-produced. Free-riding happens when one who does

not pay for the public good manages to still enjoy the benefit of that good.

Consider the following case: Ted and Doraemon are roommates and they love anime

very much. However, there is no TV in their room. Thus, the TV is a public good to them.

- If Ted buys the TV, his utility is -5 but Doraemon’s utility is +20. This is because

poor Ted needs to pay for the TV and Doraemon can free-ride (watch free TV).

- If both share the cost of the TV, both end up with a utility of +10.

- If both do not buy the TV, both end up with a utility of zero.

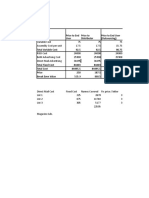

The following table shows all the possible scenarios:

Doraemon

Buy Don’t buy

Buy 10, 10 -5, 20

Ted

Don’t buy 20, -5 0, 0

The dominant strategy for both Ted and Doraemon is not to buy the TV. Thus, free-riding

prevents the public good (TV), from being provided.

9. Market for public goods (using a past year question 2014 ZA Q7)

There are 3 consumers of a public good. The demand function of the consumers are as

follows:

Consumer 1: 60

Consumer 2: 100

Consumer 3: 140

Where Q is the quantity of public good and is the price consumer is willing to pay, ∈

1,2,3 . The public good can be produced at a constant marginal cost of 180, and there

are no fixed costs.

In order to find the efficient level of production of the public good, we need to obtain the

social demand curve for the public good which is the vertical sum of the demand curves

of each consumer.

The social demand curve is 300 3

At social optimum equilibrium, → 300 3 180 → 40

Under private provision, each consumer provide the good at , ∈ 1,2,3 . But

since 180, none of the consumers will purchase the public good. That will be the

outcome for this example.

Copyright: Singapore Institute of Management Page |9

EC2066 MICROECONOMICS

Graphically, this is shown below.

P

300

180 MC

140

DS

100

60

D1 D2 D3

Q

40

Copyright: Singapore Institute of Management P a g e | 10

You might also like

- Goal and Scope of PsychotherapyDocument4 pagesGoal and Scope of PsychotherapyJasroop Mahal100% (1)

- Affiliate Marketing Beginners GuideDocument12 pagesAffiliate Marketing Beginners GuideBTS WORLDNo ratings yet

- Whelen Light CatalogDocument40 pagesWhelen Light Catalog874895No ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Intro To SociologyDocument25 pagesChapter 1 Intro To SociologyRehman AzizNo ratings yet

- MG RoverDocument19 pagesMG RoverDeepak Chiripal100% (1)

- Ret Ro Gam Er Iss Ue 168 2017Document116 pagesRet Ro Gam Er Iss Ue 168 2017Albanidis X. Kostas100% (1)

- Alexander Galloway Laruelle Against The DigitalDocument321 pagesAlexander Galloway Laruelle Against The DigitaljacquesfatalistNo ratings yet

- Steam Nozzle 1Document47 pagesSteam Nozzle 1Balaji Kalai100% (5)

- 16.life Cycle CostingDocument6 pages16.life Cycle CostingSuraj ManikNo ratings yet

- Cumberland Case Study SolutionDocument2 pagesCumberland Case Study SolutionPranay Singh RaghuvanshiNo ratings yet

- TLE-ICT-Technical Drafting Grade 10 LMDocument175 pagesTLE-ICT-Technical Drafting Grade 10 LMHari Ng Sablay87% (113)

- Curled Metal Inc. Engineered Product DivisionDocument11 pagesCurled Metal Inc. Engineered Product DivisionPaul Campbell100% (2)

- Applied Economics - First Summative Answer KeyDocument2 pagesApplied Economics - First Summative Answer KeyKarla BangFer93% (15)

- Li Fi TechnologyDocument15 pagesLi Fi TechnologyParmeshprasad Rout100% (1)

- Week 3 - ExternalitiesDocument45 pagesWeek 3 - ExternalitiesPedro Almeida LoureiroNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 - Externalities: Public FinanceDocument32 pagesChapter 4 - Externalities: Public FinanceMey MeyNo ratings yet

- CHP 8 - OligopolyDocument11 pagesCHP 8 - OligopolyEwan RidzwanNo ratings yet

- Organisation and Market Economics: Producer Theory Prof. Thiagu RanganathanDocument14 pagesOrganisation and Market Economics: Producer Theory Prof. Thiagu RanganathanBabiya MoirangthemNo ratings yet

- Lecture4. External Effects in Production and Consumption VaibhavDocument17 pagesLecture4. External Effects in Production and Consumption VaibhavVaibhav GmailNo ratings yet

- CABP Feb 07 LRDocument52 pagesCABP Feb 07 LRkarun agrawalNo ratings yet

- ECO645 Industrial Economics Market StructureDocument43 pagesECO645 Industrial Economics Market StructureMELINDA AZZALEA TAI ABDULLAH TAI NYUK CHINNo ratings yet

- Slides 2Document34 pagesSlides 2Erico MatosNo ratings yet

- Loctite Case StatsDocument8 pagesLoctite Case StatsBharat SinghNo ratings yet

- Assignment 01Document2 pagesAssignment 01Rae Jeniña E.MerelosNo ratings yet

- Forms of Business Organization, Production, and CostsDocument81 pagesForms of Business Organization, Production, and CostswillowNo ratings yet

- DME 814 Computer Integrated ManufacturingDocument42 pagesDME 814 Computer Integrated ManufacturingAtif JamilNo ratings yet

- Monopoly Market: Dr. Vaseem Akram Assistant Professor P H o N e N O: 6 3 9 8 0 1 2 8 4 9 Session No:14 Email IdDocument19 pagesMonopoly Market: Dr. Vaseem Akram Assistant Professor P H o N e N O: 6 3 9 8 0 1 2 8 4 9 Session No:14 Email IdAbhijeet MadageNo ratings yet

- Solved Cost and Demand Data For A Monopolist and Asked YouDocument1 pageSolved Cost and Demand Data For A Monopolist and Asked YouM Bilal SaleemNo ratings yet

- Solved in Both Industry C and Industry D There Are OnlyDocument1 pageSolved in Both Industry C and Industry D There Are OnlyM Bilal SaleemNo ratings yet

- Inder - Economies of Scope - AssignmentDocument3 pagesInder - Economies of Scope - AssignmentinderpalcNo ratings yet

- Pdfanddoc 29120Document71 pagesPdfanddoc 29120Abhishek Agrawal0% (1)

- Marginal Costing Decision MakingDocument3 pagesMarginal Costing Decision MakingDhanesh PatilNo ratings yet

- Biz PlanDocument4 pagesBiz Planapi-3700769No ratings yet

- Market Failure and Resource AllocationDocument32 pagesMarket Failure and Resource AllocationSandy SaddlerNo ratings yet

- Thermoid Catalogue 2017 FinalDocument204 pagesThermoid Catalogue 2017 FinalicscoNo ratings yet

- Externalities: Problems and Solutions: ExternalityDocument15 pagesExternalities: Problems and Solutions: ExternalityBin BIn100% (1)

- Chapter 08 - Pure Competition in The Short RunDocument12 pagesChapter 08 - Pure Competition in The Short RunErjon SkordhaNo ratings yet

- Crompton - LED Fitting PDFDocument52 pagesCrompton - LED Fitting PDFwritetorahulsinha9028No ratings yet

- Lecture 10Document29 pagesLecture 10Tesfaye ejetaNo ratings yet

- Master of Business Administration 2020-22: Group Assignment 2 XiameterDocument3 pagesMaster of Business Administration 2020-22: Group Assignment 2 Xiameterkusumit1011No ratings yet

- Aluminum Decarbonization at A Cost That Makes SenseDocument35 pagesAluminum Decarbonization at A Cost That Makes Senseronnie311278No ratings yet

- Economics and BCK MTP Nov18 QuestionsDocument16 pagesEconomics and BCK MTP Nov18 QuestionsDisha SethiyaNo ratings yet

- HS 200: Environmental Studies: by Neha Gupta Lecture Notes On EXTERNALITIESDocument17 pagesHS 200: Environmental Studies: by Neha Gupta Lecture Notes On EXTERNALITIESRoasted ScizorNo ratings yet

- CH 9 ExternalitiesDocument64 pagesCH 9 ExternalitiescsyscysscNo ratings yet

- MonopolyDocument32 pagesMonopolyMohammad MoshtaghianNo ratings yet

- Activity Based Costing - ExercisesDocument7 pagesActivity Based Costing - Exercises田淼No ratings yet

- Giga Casting Technology TrendDocument25 pagesGiga Casting Technology TrendGsp TonyNo ratings yet

- Rain Industries Ltd. (BSE:500339) : Stock Price: 36.00/sh Target Price: 177.00/shDocument25 pagesRain Industries Ltd. (BSE:500339) : Stock Price: 36.00/sh Target Price: 177.00/shvivekbandiNo ratings yet

- Executive Summary: Freezing Out Profits Trimester 2, 2013/14Document45 pagesExecutive Summary: Freezing Out Profits Trimester 2, 2013/14SurainiEsaNo ratings yet

- Solved A What Price Will The Profit Maximizing Monopolist Set B WhatDocument1 pageSolved A What Price Will The Profit Maximizing Monopolist Set B WhatM Bilal SaleemNo ratings yet

- Tactical Decision MakingDocument54 pagesTactical Decision MakingTika GusmawarniNo ratings yet

- JPR 54079 DailmerAG EquityResearch Report 1303Document35 pagesJPR 54079 DailmerAG EquityResearch Report 1303André Fonseca100% (1)

- PT FMDocument12 pagesPT FMNabil NizamNo ratings yet

- Case OverviewDocument9 pagesCase Overviewmayer_oferNo ratings yet

- Presented By:-Prince Saquib Narendra Minni Manish TanzinDocument25 pagesPresented By:-Prince Saquib Narendra Minni Manish TanzinPrince SachdevaNo ratings yet

- Welcome To Mergers and AcquisitionsDocument55 pagesWelcome To Mergers and AcquisitionsPranav BansalNo ratings yet

- Indirect Taxes: Central ExciseDocument15 pagesIndirect Taxes: Central ExciseShankar NarayananNo ratings yet

- Topic 5 - Pure CompetitionDocument32 pagesTopic 5 - Pure Competitionvinh96698No ratings yet

- Number 60 2019Document100 pagesNumber 60 2019Mariano Salomon PaniaguaNo ratings yet

- 08 Risk Management Failure (Case Study) - Wito SugionoDocument49 pages08 Risk Management Failure (Case Study) - Wito SugionoDody GuntamaNo ratings yet

- Solved in Some Regulated Industries Regulatory Agencies Prevented Prices From FallingDocument1 pageSolved in Some Regulated Industries Regulatory Agencies Prevented Prices From FallingM Bilal SaleemNo ratings yet

- Solved A Firm in A Competitive Industry Has A Total CostDocument1 pageSolved A Firm in A Competitive Industry Has A Total CostM Bilal SaleemNo ratings yet

- TPL Annual Report 2013 2014Document66 pagesTPL Annual Report 2013 2014piraisudi013341No ratings yet

- 13.11.2023 Economics Test Theme 3Document1 page13.11.2023 Economics Test Theme 309danielfNo ratings yet

- Monopolistic Competition: ReferenceDocument5 pagesMonopolistic Competition: ReferenceSabu VincentNo ratings yet

- Solved Do You Think Any of The Following Industries Might BeDocument1 pageSolved Do You Think Any of The Following Industries Might BeM Bilal SaleemNo ratings yet

- Carbon Market To Be Smaller SideDocument5 pagesCarbon Market To Be Smaller SideAjay DhamijaNo ratings yet

- Performance Management: Monday 8 June 2009Document10 pagesPerformance Management: Monday 8 June 2009shanoo69No ratings yet

- N13 2013 Intro To Economics Chapter 12 - Macro IntroDocument16 pagesN13 2013 Intro To Economics Chapter 12 - Macro IntroRick DiazNo ratings yet

- L11 AsyInfoDocument19 pagesL11 AsyInfoRick DiazNo ratings yet

- L09 OligopolyDocument45 pagesL09 OligopolyRick DiazNo ratings yet

- L08-Game TheoryDocument20 pagesL08-Game TheoryRick DiazNo ratings yet

- Articulo en Jurnal Nature of MedicineDocument13 pagesArticulo en Jurnal Nature of MedicineIngeniería Alpa TelecomunicacionesNo ratings yet

- XMLReports DownloadattachmentprocessorDocument44 pagesXMLReports DownloadattachmentprocessorjayapavanNo ratings yet

- Complexation Lect 1Document32 pagesComplexation Lect 1Devious HunterNo ratings yet

- CH-8 - Rise of Indian NationalismDocument3 pagesCH-8 - Rise of Indian NationalismdebdulaldamNo ratings yet

- Thomas Hardy-A Labyrinthic NovelistDocument4 pagesThomas Hardy-A Labyrinthic NovelistFlorinaVoiteanuNo ratings yet

- International Strategies Group, LTD v. Greenberg Traurig, LLP Et Al - Document No. 74Document8 pagesInternational Strategies Group, LTD v. Greenberg Traurig, LLP Et Al - Document No. 74Justia.comNo ratings yet

- User Manual HP Officejet 8210Document95 pagesUser Manual HP Officejet 8210ponidiNo ratings yet

- PRP ConsentDocument4 pagesPRP ConsentEking InNo ratings yet

- Chapter 24 - Glass and Glazing PDFDocument14 pagesChapter 24 - Glass and Glazing PDFpokemonNo ratings yet

- JCB Case StudyDocument2 pagesJCB Case Studysbph_iitm0% (1)

- Form AK - Additional PageDocument3 pagesForm AK - Additional PagekatacumiNo ratings yet

- Sci8 Q4 M4 Classifications-of-Living-OrganismsDocument27 pagesSci8 Q4 M4 Classifications-of-Living-OrganismsJeffrey MasiconNo ratings yet

- ST ND: Page 1 of 3 BAC Reso No. - S. 2020Document3 pagesST ND: Page 1 of 3 BAC Reso No. - S. 2020Federico DomingoNo ratings yet

- Learning From Others and Reviewing Literature: Zoila D. Espiritu, L.P.T., M.A.Ed. Stephanie P. MonteroDocument10 pagesLearning From Others and Reviewing Literature: Zoila D. Espiritu, L.P.T., M.A.Ed. Stephanie P. Monterochararat marnieNo ratings yet

- Activity 1 CONDUCTING AN INTERVIEW WITH AN OFWDocument5 pagesActivity 1 CONDUCTING AN INTERVIEW WITH AN OFWSammuel De BelenNo ratings yet

- Human Body: Digestion - Pathway and EnzymesDocument4 pagesHuman Body: Digestion - Pathway and EnzymesDiana VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- FDARDocument2 pagesFDARMikaella JumandosNo ratings yet

- Ricardo Vargas Simplified Pmbok Flow 6ed PROCESSES EN-A4 PDFDocument1 pageRicardo Vargas Simplified Pmbok Flow 6ed PROCESSES EN-A4 PDFFrancisco Alfonso Durán MaldonadoNo ratings yet

- Saltwater Aquarium Guide: What's The Difference Between Saltwater and Freshwater? WhereasDocument10 pagesSaltwater Aquarium Guide: What's The Difference Between Saltwater and Freshwater? WhereasTimmy HendoNo ratings yet

- Nemo Analyze: Professional Post-Processing of Drive Test DataDocument21 pagesNemo Analyze: Professional Post-Processing of Drive Test DataMohammed ShakilNo ratings yet

- Ar. Laurie BakerDocument21 pagesAr. Laurie BakerHardutt Purohit100% (1)