Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Robinson Crusoe - Excerpt 1

Robinson Crusoe - Excerpt 1

Uploaded by

LikhonaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Robinson Crusoe - Excerpt 1

Robinson Crusoe - Excerpt 1

Uploaded by

LikhonaCopyright:

Available Formats

Robinson Crusoe – Excerpt 1

It was a little before the great rains just now mentioned that I threw this stuff away, taking no notice,

and not so much as remembering that I had thrown anything there, when, about a month after, or

thereabouts, I saw some few stalks of something green shooting out of the ground, which I fancied

might be some plant I had not seen; but I was surprised, and perfectly astonished, when, after a little

longer time, I saw about ten or twelve ears come out, which were perfect green barley, of the same

kind as our European - nay, as our English barley.

It is impossible to express the astonishment and confusion of my thoughts on this occasion. I had

hitherto acted upon no religious foundation at all; indeed, I had very few notions of religion in my

head, nor had entertained any sense of anything that had befallen me otherwise than as chance, or, as

we lightly say, what pleases God, without so much as inquiring into the end of Providence in these

things, or His order in governing events for the world. But after I saw barley grow there, in a climate

which I knew was not proper for corn, and especially that I knew not how it came there, it startled

me strangely, and I began to suggest that God had miraculously caused His grain to grow without

any help of seed sown, and that it was so directed purely for my sustenance on that wild, miserable

place.

This touched my heart a little, and brought tears out of my eyes, and I began to bless myself that such

a prodigy of nature should happen upon my account; and this was the more strange to me, because I

saw near it still, all along by the side of the rock, some other straggling stalks, which proved to be

stalks of rice, and which I knew, because I had seen it grow in Africa when I was ashore there.

I not only thought these the pure productions of Providence for my support, but not doubting that

there was more in the place, I went all over that part of the island, where I had been before, peering

in every corner, and under every rock, to see for more of it, but I could not find any. At last it occurred

to my thoughts that I shook a bag of chickens’ meat out in that place; and then the wonder began to

cease; and I must confess my religious thankfulness to God’s providence began to abate, too, upon

the discovering that all this was nothing but what was common; though I ought to have been as

thankful for so strange and unforeseen a providence as if it had been miraculous; for it was really the

work of Providence to me, that should order or appoint that ten or twelve grains of corn should remain

unspoiled, when the rats had destroyed all the rest, as if it had been dropped from heaven; as also,

that I should throw it out in that particular place, where, it being in the shade of a high rock, it sprang

up immediately; whereas, if I had thrown it anywhere else at that time, it had been burnt up and

destroyed.

I carefully saved the ears of this corn, you may be sure, in their season, which was about the end of

June; and, laying up every corn, I resolved to sow them all again, hoping in time to have some

quantity sufficient to supply me with bread. But it was not till the fourth year that I could allow

myself the least grain of this corn to eat, and even then but sparingly, as I shall say afterwards, in its

order; for I lost all that I sowed the first season by not observing the proper time; for I sowed it just

before the dry season, so that it never came up at all, at least not as it would have done; of which in

its place.

Besides this barley, there were, as above, twenty or thirty stalks of rice, which I preserved with the

same care and for the same use, or to the same purpose - to make me bread, or rather food; for I found

ways to cook it without baking, though I did that also after some time.

Defoe (2008:67-68)

Defoe, D. 2008. Robinson Crusoe. Oxford: Oxford university press.

You might also like

- Introduction To Restaurant ServiceDocument5 pagesIntroduction To Restaurant ServiceHazwani HamzahNo ratings yet

- Daniel Defoe - Robinson CrusoeDocument418 pagesDaniel Defoe - Robinson CrusoeWaterwind90% (10)

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe by Defoe, Daniel, 1661-1731Document123 pagesThe Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe by Defoe, Daniel, 1661-1731Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Life Lines: A Shared Reading Activity Pack To Read Wherever You Are Issue 86Document12 pagesLife Lines: A Shared Reading Activity Pack To Read Wherever You Are Issue 86ShamonNo ratings yet

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Author Daniel DefoeDocument103 pagesThe Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Author Daniel DefoeSyedNo ratings yet

- The Further Adventures of Robinson CrusoeDocument149 pagesThe Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoekishku123No ratings yet

- Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)From EverandFurther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (39)

- Adventures in Contentment by Grayson, David, 1870-1946Document104 pagesAdventures in Contentment by Grayson, David, 1870-1946Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe: "The soul is placed in the body like a rough diamond, and must be polished, or the luster of it will never appear"From EverandThe Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe: "The soul is placed in the body like a rough diamond, and must be polished, or the luster of it will never appear"No ratings yet

- M.apart-1 Pbi Sem-1 17-11-2022 Roll NoDocument35 pagesM.apart-1 Pbi Sem-1 17-11-2022 Roll NoshubhreettkaurrNo ratings yet

- Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe: [Next Stories of Robinson Crusoe]From EverandFurther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe: [Next Stories of Robinson Crusoe]No ratings yet

- Far Away and Long Ago (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): A History of My Early LifeFrom EverandFar Away and Long Ago (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): A History of My Early LifeNo ratings yet

- Where I Lived and What I Lived ForDocument10 pagesWhere I Lived and What I Lived ForNaveenNo ratings yet

- A Crystal Age (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)From EverandA Crystal Age (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (17)

- David-Copperfield Charles Dickens OriginalDocument1,586 pagesDavid-Copperfield Charles Dickens OriginalElis AlvesNo ratings yet

- The Anglican Friar and the Fish which he Took by Hook and by CrookFrom EverandThe Anglican Friar and the Fish which he Took by Hook and by CrookNo ratings yet

- The Farther Adventures Of Robinson CrusoeFrom EverandThe Farther Adventures Of Robinson CrusoeRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (45)

- The Parish Trilogy: Annals of a Quiet Neighbourhood, The Seaboard Parish & The Vicar's DaughterFrom EverandThe Parish Trilogy: Annals of a Quiet Neighbourhood, The Seaboard Parish & The Vicar's DaughterNo ratings yet

- Great Possessions by Grayson, David, 1870-1946Document90 pagesGreat Possessions by Grayson, David, 1870-1946Gutenberg.org100% (1)

- UntitledDocument539 pagesUntitledJ.B. ShankNo ratings yet

- Crowley - Liber DCCCLX, John St. JohnDocument119 pagesCrowley - Liber DCCCLX, John St. JohnCelephaïs Press / Unspeakable Press (Leng)100% (2)

- Robinson CrusoeDocument487 pagesRobinson CrusoeLord CapuletNo ratings yet

- Robinson Crusoe (English)Document200 pagesRobinson Crusoe (English)marcosNo ratings yet

- The Five Jars by James, M. R. (Montague Rhodes), 1862-1936Document46 pagesThe Five Jars by James, M. R. (Montague Rhodes), 1862-1936Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Rilke RequiemDocument14 pagesRilke RequiemTodd Leong100% (2)

- Egyptian Creation: DAY 1 - Creation of LightDocument4 pagesEgyptian Creation: DAY 1 - Creation of LightJerico LlovidoNo ratings yet

- The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 17, No. 474, Supplementary Number by VariousDocument35 pagesThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 17, No. 474, Supplementary Number by VariousGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- PDF of Sulaiman As Raja Segala Makhluk Humam Hasan Yusuf Shalom Full Chapter EbookDocument69 pagesPDF of Sulaiman As Raja Segala Makhluk Humam Hasan Yusuf Shalom Full Chapter Ebookkaymanmanofi100% (3)

- Doolittle On Queen-RearingDocument184 pagesDoolittle On Queen-RearingGML2100% (1)

- Selections From - Robinson CrusoeDocument1 pageSelections From - Robinson CrusoedanynikeNo ratings yet

- Frankestein 216 262Document47 pagesFrankestein 216 262Lily Suarez CamNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Econ Macroeconomics 4 4th Edition Mceachern Solutions Manual PDF ScribdDocument32 pagesInstant Download Econ Macroeconomics 4 4th Edition Mceachern Solutions Manual PDF ScribdJoseph Benson100% (18)

- Story Book 2Document393 pagesStory Book 2Somnath KumbharNo ratings yet

- Paracelsus - Robert Browning (1898)Document174 pagesParacelsus - Robert Browning (1898)WaterwindNo ratings yet

- Gehl Forage Harvester 1075 Operators Manual 908018aDocument22 pagesGehl Forage Harvester 1075 Operators Manual 908018akathleenflores140886xgk100% (128)

- A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy by Sterne, Laurence, 1713-1768Document71 pagesA Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy by Sterne, Laurence, 1713-1768Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- 4 English Paper Specimen Sinbad The Sailor Extract.254318134Document2 pages4 English Paper Specimen Sinbad The Sailor Extract.254318134Jim NielsenNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Financial Accounting Theory Canadian 7th Edition Scott Solutions Manual PDF Full ChapterDocument33 pagesInstant Download Financial Accounting Theory Canadian 7th Edition Scott Solutions Manual PDF Full Chapterphuhilaryyact2100% (8)

- Full Download Test Bank For Essentials of Geology 6th Edition Stephen Marshak PDF FreeDocument32 pagesFull Download Test Bank For Essentials of Geology 6th Edition Stephen Marshak PDF Freeandreasmithpitornwgbc100% (11)

- Global PVT LTDDocument12 pagesGlobal PVT LTDmohitdesigntreeNo ratings yet

- Đề Và Đáp Án Anh 10 - Chuyên Yên BáiDocument20 pagesĐề Và Đáp Án Anh 10 - Chuyên Yên BáiDuy Hải0% (1)

- Full Download Ebook PDF Investigating Oceanography 3rd Edition by Keith Sverdrup PDFDocument41 pagesFull Download Ebook PDF Investigating Oceanography 3rd Edition by Keith Sverdrup PDFjason.lollar844100% (38)

- ProfilHotels Nacka, Stockholm - Updated 2023 PricesDocument1 pageProfilHotels Nacka, Stockholm - Updated 2023 Pricesmajusias04No ratings yet

- MyBestReading1 Answer KeyDocument12 pagesMyBestReading1 Answer KeytinarockfulNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument24 pagesUntitledthai nguyenNo ratings yet

- FBS Pre & PostDocument2 pagesFBS Pre & PostgayNo ratings yet

- Bread Item Allergies Ingredients Description: Sant AmbroeusDocument7 pagesBread Item Allergies Ingredients Description: Sant AmbroeusAlc DinuNo ratings yet

- Tle Go Grow GlowDocument2 pagesTle Go Grow GlowMaria Fe GonzagaNo ratings yet

- 03 - G6 Maths Tutor 6A Tutorial 3 (Ratio) - DESKTOP-QQ5URHVDocument36 pages03 - G6 Maths Tutor 6A Tutorial 3 (Ratio) - DESKTOP-QQ5URHVnightmearalphaNo ratings yet

- Giving Advice (Should / Shouldn'T) : Match The Situations With The Pieces of AdviceDocument1 pageGiving Advice (Should / Shouldn'T) : Match The Situations With The Pieces of AdviceBARBARA JACQUELINE VILLASEÑOR PÉREZNo ratings yet

- Term Paper On GoingDocument9 pagesTerm Paper On GoingChristian VillaNo ratings yet

- Ch.8 Plantae ModuleDocument3 pagesCh.8 Plantae ModuleEMIL SALNo ratings yet

- ACTIVITY #1 F&B Organizational Structure of A Small Scale Food Service OperationDocument6 pagesACTIVITY #1 F&B Organizational Structure of A Small Scale Food Service OperationPat BersolaNo ratings yet

- SimplenPastnUSnStudent 9564fa941b261beDocument14 pagesSimplenPastnUSnStudent 9564fa941b261bemeli suarezNo ratings yet

- Day 3Document5 pagesDay 3LaurenNo ratings yet

- Tugas 3Document20 pagesTugas 3ssiahaan215No ratings yet

- Date Palm Cultivation in IndiaDocument14 pagesDate Palm Cultivation in IndiasuggyNo ratings yet

- Bariatric Nutrition GuideDocument36 pagesBariatric Nutrition GuideEmaDiaconuNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Biodiversity 生物多样性: Diversity 多样化 of Organisms 生物Document138 pagesChapter 2 Biodiversity 生物多样性: Diversity 多样化 of Organisms 生物YAP SHAN MoeNo ratings yet

- LET Reviewer General Education GenEd - Science Part 1Document15 pagesLET Reviewer General Education GenEd - Science Part 1HikareNo ratings yet

- Climate-Smart Livestock Production Systems in Practice: B2-3.1 Land-Based SystemsDocument8 pagesClimate-Smart Livestock Production Systems in Practice: B2-3.1 Land-Based SystemsObo KeroNo ratings yet

- Dialogues and Situations: InvitationDocument19 pagesDialogues and Situations: InvitationalialkhataryNo ratings yet

- KoreanDocument13 pagesKoreangetzydchristNo ratings yet

- Hapag OrdinanceDocument3 pagesHapag OrdinanceKent Charles NotarioNo ratings yet

- Project WorkDocument21 pagesProject WorkAjay SagarNo ratings yet

- Nutri LEC AssignmentDocument3 pagesNutri LEC AssignmentJohnNo ratings yet

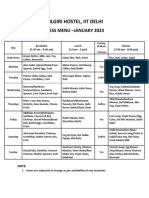

- Mess Menu January NilDocument1 pageMess Menu January NilShwetabh SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Bontoc SummaryDocument2 pagesBontoc SummaryChristine ArmilNo ratings yet

![Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe: [Next Stories of Robinson Crusoe]](https://imgv2-1-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/371444032/149x198/541629e46a/1617230284?v=1)