Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Internal Medicine Journal - 2018 - Young - Meningitis in Adults Diagnosis and Management

Internal Medicine Journal - 2018 - Young - Meningitis in Adults Diagnosis and Management

Uploaded by

aslan tonapaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Internal Medicine Journal - 2018 - Young - Meningitis in Adults Diagnosis and Management

Internal Medicine Journal - 2018 - Young - Meningitis in Adults Diagnosis and Management

Uploaded by

aslan tonapaCopyright:

Available Formats

Kaye had a deep interest in medical history and was a College and to medical research and practice in

founding member of the Auckland Medical History Soci- New Zealand and Australia, and he will be greatly

ety, which he chaired for many years. He was instru- missed by his many friends and colleagues.

mental in establishing the Ernest and Marion Davis

Received 21 March 2018; accepted 6 April 2018.

Memorial Library and Lecture Halls on the Auckland

Hospital site, a great asset to the local medical commu- Ian Holdaway and Ian Reid

nity. Kaye was a keen trout fisherman, beekeeper and Department of Endocrinology, Auckland Hospital and Greenlane

antiquarian. He made an immense contribution to the Clinical Centre, Auckland, New Zealand

doi:10.1111/imj.14102

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVES

Meningitis in adults: diagnosis and management

1 1,2

Nicholas Young and Mark Thomas

1

Department of Infectious Diseases, Auckland City Hospital, and 2Department of Molecular Medicine and Pathology, University of Auckland, Auckland,

New Zealand

Key words Abstract

meningitis, CT scan, lumbar puncture,

cerebrospinal fluid, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Bacterial meningitis is a medical emergency. All clinicians who provide acute medical

Neisseria meningitidis. care require a sound understanding of the priorities of managing a patient with sus-

pected meningitis during the first hour. These include obtaining blood cultures, per-

Correspondence forming lumbar puncture and initiating appropriate therapy, while avoiding harmful

Nicholas Young, Department of Infectious delays such as those that result from not administering treatment until neuroimaging

Diseases, Level 6 Support Building, Auckland has been performed. Despite the increasing availability of newer diagnostic techniques,

City Hospital, Private Bag 92024, Grafton Road, the interpretation of cerebrospinal fluid parameters remains a vital skill for clinicians.

Grafton, Auckland 1030, New Zealand. International and local guidelines differ with regard to initial empirical therapy of bacte-

Email: nicholasy@adhb.govt.nz rial meningitis in adults; the North American guideline recommends ceftriaxone and

vancomycin for all patients, while the Australian, UK and European guidelines recom-

Received 22 March 2018; accepted mend that vancomycin only be added for patients who are more likely to have pneu-

5 August 2018. mococcal meningitis or who have a higher likelihood of being infected with a strain of

Streptococcus pneumoniae with reduced susceptibility to ceftriaxone. Patients with risk fac-

tors for Listeria meningitis also require an anti-Listeria agent, such as benzylpenicillin, to

be added to this treatment regimen. Dexamethasone should be a routine component of

empirical therapy due to its proven role in reducing morbidity and mortality from

pneumococcal meningitis.

Introduction It is critical that clinicians recognise the need to prioritise

initial investigations while not delaying life-saving treat-

Bacterial meningitis is a potentially catastrophic infec-

ment with dexamethasone and antibiotics, which should

tious disease associated with substantial mortality and a

be administered as soon as possible within the first hour

risk of permanent disability in survivors.1 Despite ongo-

following presumptive diagnosis. This article will focus

ing advances in diagnostic methods and treatment strate-

on diagnostic and management issues that a clinician

gies, mortality remains as high as 30% in pneumococcal

will face when dealing with a suspected case of

meningitis and 5–10% in meningococcal meningitis.2,3

community-acquired bacterial meningitis in an adult.

However, outcomes are improved by prompt therapy.4–6

While we do not address non-infectious causes of men-

ingitis, such as those caused by malignancy, medications

Funding: None. or autoimmune conditions, these should also be consid-

Conflict of interest: None. ered in the differential diagnosis of meningitis.

1294 Internal Medicine Journal 48 (2018) 1294–1307

© 2018 Royal Australasian College of Physicians

Meningitis in adults

Diagnosis starting treatment and increases the likelihood of an

unfavourable outcome.6 Second, the yield of CT is low in

Clinical features and clues to the responsible patients who do not have clinical features of raised intra-

pathogen cranial pressure (ICP), with 97% having a normal

result.12 Third, if a patient is pretreated with antibiotics

A patient who presents with recent onset of headache, prior to CT and LP, the yield of CSF culture will be signif-

fever, neck stiffness or altered mental state would icantly decreased, although a diagnosis can often still be

prompt most clinicians to consider the possibility of men- obtained through polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

ingitis. At least two of these four features will be present testing.11

in 95% of patients with bacterial meningitis and should CT prior to LP is recommended for patients who have

lead to urgent diagnostic work-up for this condition.7 one or more clinical features that increase the probability

The classic triad of bacterial meningitis consists of fever, of having raised ICP, to attempt to identify those most at

neck stiffness and altered mental state; however, reliance risk of brain herniation following LP. However, guide-

on all three of these signs being present will result in lines differ as to which clinical features constitute an

more than 50% of cases of bacterial meningitis being indication to perform CT prior to LP (Table 1). The lack

missed.7 of consensus about which patients should undergo a CT

Some clinical features and patient characteristics may prior to LP reflects uncertainties about the reliability of

provide clues to the responsible pathogen. Meningitis CT scans to detect raised ICP16 and about whether CT

due to Neisseria meningitidis may begin with an influenza- evidence of raised ICP is associated with an increased

like illness, with symptoms such as fever, muscle aches risk of brain herniation following LP.4 Scepticism of the

and vomiting, before meningitis becomes clinically value of neuroimaging is reflected in the Swedish

apparent. Rapid onset and progression of symptoms over guideline,15 which recommends CT prior to LP only for

hours is typical and can be helpful to distinguish this patients who have signs of imminent brain herniation,

condition from self-limiting viral infections. A patient focal neurological deficits (not including cranial nerve

with meningitis and a non-blanching petechial or purpu- palsies) or who have had cerebral symptoms for more

ric rash strongly suggests meningococcal disease, than 4 days (which increases the likelihood of cerebral

although the rash may also be blanching, maculopapular pathology other than acute meningitis). A recent study

or absent. The level of suspicion must be particularly suggested that use of the Swedish guideline in place of

high for patients presenting in the context of an estab- the Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline

lished meningococcal epidemic.8 Meningitis due to Strep- might result in a shorter time to initiation of therapy, an

tococcus pneumoniae should be suspected in patients with approximately 33% reduction in mortality and an

predisposing conditions, such as otitis media, sinusitis, approximately 24% increase in favourable outcome in

mastoiditis, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak, cochlear patients with bacterial meningitis.17 This suggests that

implants, asplenia, human immunodeficiency virus more stringent selection of patients who undergo CT

(HIV) infection or other immunosuppressive conditions before LP has the potential to significantly improve out-

or medications.9 Patients at risk of Listeria monocytogenes comes in patients with bacterial meningitis. If CT before

meningitis include those aged ≥50, those taking long- LP is deemed to be necessary, it is vital that blood cul-

term glucocorticoids or other immunosuppressive drugs tures are taken, and dexamethasone and antibiotics are

and those with diabetes, alcoholism, cirrhosis, end-stage started without delay.

renal failure, malignancy, HIV infection or organ

transplantation.10

CSF analysis

CSF analysis is of vital importance in suspected meningitis

Neuroimaging: computed tomography before

as clinical characteristics alone are unable to distinguish

lumbar puncture is not usually required

meningitis from other diagnoses, and bacterial from non-

In many patients with meningitis, performing a lumbar bacterial aetiologies.18 For the majority of patients who do

puncture (LP) and starting empirical treatment are not require CT prior to LP and do not have another clini-

unnecessarily delayed while waiting for computed cal contraindication to LP, CSF analysis should be per-

tomography (CT) of the head.11 CT prior to LP should formed within 1 h of the presumptive diagnosis

not be performed for most patients for several reasons. of meningitis without awaiting further investigations,

First, and most importantly, if a patient is not pretreated such as platelet count or coagulation studies. Clinical con-

with antibiotics, the sequence of CT followed by LP fol- traindications to LP include anticoagulation, clinical evi-

lowed by antibiotics causes an unacceptable delay in dence of disseminated intravascular coagulation and local

Internal Medicine Journal 48 (2018) 1294–1307 1295

© 2018 Royal Australasian College of Physicians

Young & Thomas

Table 1 Indications for CT head prior to LP

IDSA guideline13 ESCMID guideline14 Swedish guideline15

Immunosuppression HIV infection, immunosuppressive therapy, Severely immunocompromised Not an indication for CT

post-transplantation state

Background of CNS Mass lesion, stroke or focal CNS infection No recommendation Not an indication for CT

disease

Seizures Seizures within a week prior to presentation New onset seizures Not an indication for CT

Level of GCS < 15 GCS < 10 ‘Imminent herniation’: unconscious plus one

consciousness or more of rigid dilated pupils, increased

BP and bradycardia, abnormal respirations,

opisthotonus, loss of all reactions

Focal neurological Focal deficit including cranial nerve palsies Focal deficit excluding cranial Focal deficit excluding cranial nerve palsies

deficit nerve palsies

Papilloedema Indication for CT No recommendation Avoid LP if present but fundoscopy not

mandatory

Duration of No recommendation No recommendation >4 days of cerebral symptoms

symptoms

BP, blood pressure; CNS, central nervous system; CT, computed tomography; ESCMID, European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Dis-

eases; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IDSA, Infectious Diseases Society of America; LP, lumbar puncture.

infection or loss of skin integrity at the puncture site.19 LP devices are present.1 The likelihood of a positive Gram

is safe in patients taking aspirin, but safety is less well stain ranges from 25% to 97% and is highly correlated

established for those taking other anti-platelet agents, with the concentration of bacterial colony-forming units

such as clopidogrel or ticagrelor, or for those on dual anti- in the CSF; a negative stain therefore cannot exclude this

platelet therapy; deferring LP is recommended in these diagnosis.13 A positive Gram stain is more likely in pneu-

circumstances.19 mococcal meningitis compared with meningococcal or

Listeria meningitis and is less likely if antibiotics have

Appearance and opening pressure been given prior to LP.20

Appearance of the CSF should be noted; cloudy or turbid

fluid suggests a significant concentration of leukocytes in Cell counts and chemistry

the sample (although xanthochromia, elevated protein If the Gram stain is negative, the CSF leukocyte count is

concentration or a high number of bacterial colony- often helpful in distinguishing bacterial from non-

forming units may also cause this appearance).13 A bacterial meningitis (Table 2). Meningitis is confirmed

manometer should be used to measure opening pressure when the leukocyte count in the CSF exceeds 5 cells/μL.

in the lateral decubitus position; in bacterial meningitis, A leukocyte count of ≥1000 cells/μL with a neutrophilic

opening pressure is typically >20 cm H2O, although predominance is highly suggestive of bacterial

other factors, such as patient anxiety and positioning, meningitis,1 whereas <1000 cells/μL with a lymphocytic

may artifactually elevate this.13 predominance is more consistent with viral meningitis,

tuberculous meningitis (TBM) or cryptococcal meningi-

Gram stain

tis.20 Bacterial meningitis due to L. monocytogenes is an

Once CSF is delivered to the laboratory, a Gram stain important exception, with approximately 60% of cases

should be rapidly performed. If bacteria are seen, this having a leukocyte count of <1000 cells/μL, which may

provides a presumptive microbiological diagnosis upon be lymphocytic.10 If a traumatic tap occurs, the leukocyte

which directed therapy can be based.13 The presence of count should be corrected by deducting one leukocyte

Gram-positive cocci suggests S. pneumoniae, Gram- for every 500–1000 red cells in the CSF.23

negative diplococci N. meningitidis and Gram-positive It is critical that these leukocyte ranges are not viewed

bacilli L. monocytogenes (which are the first, second and as absolute cut-off values. Bacterial meningitis can pre-

third most common causes of community-acquired bac- sent with counts significantly lower than 1000 cells/μL,

terial meningitis in adults, respectively).10 Gram- and rare cases with normal counts on initial CSF analysis

negative bacillary meningitis is rare in immune- have been described.24 In addition, 10% of cases have a

competent adults unless indwelling neurosurgical lymphocytic predominance.13 In very early presentations

1296 Internal Medicine Journal 48 (2018) 1294–1307

© 2018 Royal Australasian College of Physicians

Meningitis in adults

Table 2 Typical CSF findings in healthy adults and adult patients with meningitis1,13,20–22

Opening pressure CSF leukocytes Predominant cell type CSF CSF-to-blood glucose

(cm H2O) (cells/μL) protein (g/L) ratio

Normal CSF ≤20 0–5 Lymphocytes 0.15–0.45 0.6

Bacterial meningitis† >20 ≥1000 Neutrophils ≥1.0 ≤0.5

Viral meningitis‡ ≤20 <1000 Lymphocytes (may be <1.0 0.6

neutrophilic within first 48 h)

Tuberculous Normal or elevated 100–500 Lymphocytes ≥1.0 ≤0.5

meningitis

Eosinophilic meningitis Normal or elevated <1000 ≥10% eosinophils <1.0 0.6

Cryptococcal >20 <200 Lymphocytes >0.45 ≤0.5

meningitis

†Excluding Listeria meningitis, where CSF leukocytes are often <1000 cells/μL and CSF may be lymphocytic. ‡Excluding HSV and VZV meningitis,

where protein may be ≥1.0 g/L. CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; HSV, herpes simplex virus; VZV, varicella zoster virus.

of viral meningitis, there may be a neutrophilic predomi- Culture

nance, which typically becomes lymphocytic within

The sensitivity of culture is 60–90% for CSF collected

48 h.25

before antibiotic treatment has been started, with posi-

CSF protein is usually elevated in meningitis of both

tive results generally available within 24–48 h.13 The

bacterial and viral aetiology due to increased perme-

yield of culture decreases significantly in the pretreated

ability of the blood–brain barrier as a consequence of

patient, in whom other tests, such as PCR or bacterial

inflammation.1 This elevation is typically greater in

antigen testing (BAT), may be necessary to identify the

bacterial and TBM (≥1 g/L) than in viral meningitis

pathogen. In addition to CSF cultures, blood cultures

(<1 g/L), with the exception of meningitis due to the

should be taken in all cases of suspected bacterial men-

herpes simplex virus (HSV) or varicella zoster virus

ingitis as a pathogen may be isolated through this route

(VZV), where protein may be ≥1 g/L.20,26 As with the

despite negative Gram stain and culture of CSF.14

leukocyte count, CSF protein should be corrected for a

traumatic tap by deducting 0.01 g/L for every 1000 red Bacterial antigen testing

cells.23

Hypoglycorrhachia (low CSF glucose) is another help- Many laboratories offer BAT on CSF samples, most often

ful pointer towards bacterial meningitis, although it is for the detection of S. pneumoniae. The pneumococcal

also seen in TBM and cryptococcal meningitis.21,27 CSF BAT has been reported to have a specificity in excess of

glucose varies proportionally to blood glucose, with a 95% for pneumococcal meningitis and a sensitivity rang-

normal CSF-to-blood glucose ratio being 0.6.28 A normal ing between 67% and 100%.13 This test can be per-

ratio is usually found in viral meningitis.20 A ratio of formed within minutes of the sample arriving in the

≤0.5 has 100% sensitivity for bacterial meningitis but laboratory and can provide more rapid confirmation of

specificity of only 57%.22 When a ratio of ≤0.23 is used, pneumococcal meningitis than either PCR or culture.

specificity improves to 99% but at the cost of sensitiv- However, given the variable sensitivity of this test, a neg-

ity.29 These values are minimally affected by pretreat- ative pneumococcal BAT should not justify the early dis-

ment with antibiotics. The CSF-to-blood glucose ratio continuation of S. pneumoniae-specific therapy, such as

may be less helpful in hyperglycaemic patients as CSF dexamethasone or vancomycin, if this has been com-

glucose levels begin to plateau once blood glucose menced. In Australia, a positive pneumococcal BAT is

exceeds 5.5 mmol/L (100 mg/dL).28 considered an indication for adding vancomycin to the

Given that no single CSF parameter can reliably dis- empirical antibiotic regimen.31

tinguish bacterial from non-bacterial causes of meningi-

Polymerase chain reaction

tis, clinicians must exercise caution when interpreting

these parameters. Consideration of clinical features and Multiplex PCR assays can detect the presence of many

CSF parameters together often cannot confidently important bacterial and viral pathogens in CSF, including

exclude the possibility that a patient has bacterial men- N. meningitidis, S. pneumoniae, enteroviruses, HSV, VZV

ingitis. In these cases, most experienced clinicians and mumps virus, with sensitivity and specificity

would err on the side of caution and treat for bacterial ≥90%.13 Misleading positive viral results have occasion-

meningitis while awaiting further microbiological ally been described in cases of confirmed bacterial men-

results.30 ingitis.32 PCR has been used successfully for the

Internal Medicine Journal 48 (2018) 1294–1307 1297

© 2018 Royal Australasian College of Physicians

Young & Thomas

diagnosis of Listeria meningitis, but assays are not yet HIV RNA. This was detected in three patients, two of

widely available.33 In Australia and New Zealand, the whom had acute HIV infection as the likely cause for

accessibility of multiplex PCR varies based on location; a their presentation. None had been prospectively

result can be available within hours if the assay is avail- diagnosed.41

able in-house but may take days if the sample needs to Not all patients with aseptic meningitis have viral

be delivered to a reference laboratory. When compared meningitis, and it is important to consider other causes if

with bacterial culture, PCR is much less affected by pre- a viral aetiology is not confirmed by PCR.42 Suspicion for

treatment with antibiotics, with one study showing sen- a non-viral aetiology should be heightened in those with

sitivity of 89% in samples collected on days 1–3 of a subacute presentation, in immunosuppressed patients,

antibiotic treatment, 70% on days 4–6 and 33% on days in people from tuberculosis-endemic countries, in those

7–10. In comparison, no CSF cultures were positive in with risk factors for sexually transmitted infection and in

samples collected more than 1 day after initiation of those with exposure to farm animals, faecally contami-

antibiotics.34 nated water or who have recently travelled to countries

in Southeast Asia or the Pacific region.

Cryptococcal meningitis should be considered in

Lactate, procalcitonin and C-reactive protein

patients with a subacute presentation. While this disease

CSF lactate, serum procalcitonin (PCT) and serum C- is commonly associated with acquired immunodefi-

reactive protein (CRP) may be helpful in distinguishing ciency syndrome (AIDS) or other forms of immunosup-

bacterial from non-bacterial meningitis. A meta-analysis pression, it can also occur in seemingly

reported that a CSF lactate of ≥35 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L) immunocompetent people; amongst HIV negative

had 93% sensitivity and 99% specificity for bacterial patients with cryptococcal meningitis, 30% have no

meningitis.35 CSF lactate is not proportional to serum identifiable risk factors for this disease.21 Typical CSF

lactate, but it may be elevated in central nervous system parameters are shown in Table 2, although cryptococcal

(CNS) conditions other than bacterial meningitis, such as meningitis can be present despite normal CSF parame-

viral encephalitis or seizures.14 Another meta-analysis ters in patients with HIV infection.43 A high opening

showed that elevated serum PCT had 90% sensitivity pressure is characteristic of this condition, and the diag-

and 98% specificity for bacterial meningitis and was nosis can be confirmed through CSF analysis for crypto-

more sensitive and specific than CRP; the definition of coccal antigen, India ink staining and fungal cultures,

elevated PCT varied between the individual studies, with which are positive in 97%, 51% and 89% of HIV-

cut-off values from ≥0.25 to ≥2.13 ng/mL (normal <0.1 negative cases respectively.21

ng/mL).36 PCT is particularly helpful in the diagnosis of TBM can present as either an acute or subacute illness

early bacterial meningitis as it becomes detectable within and should be considered in people who have lived in a

3–4 h of onset of symptoms, compared with the 12–24 h low- or middle-income country. If TBM is suspected, a

that CRP takes to rise.37 When PCT measurement is not large volume of CSF (10–20 mL) should be sent to the

readily available, CRP may provide some useful informa- lab for acid-fast stain, PCR (such as with the GeneXpert

tion; one study showed that patients with bacterial men- MTB/RIF system) and mycobacterial cultures (which

ingitis had a median CRP of 162 mg/L (95% confidence require incubation for up to 6 weeks).27 The yield of

interval 39–275) compared with a median of 13 mg/L these investigations is improved by testing large volumes

(95% confidence interval 9–17) in non-bacterial menin- of CSF, but all tests suffer from imperfect sensitivity,

gitis.38 Pretreatment with antibiotics decreases the sensi- which is approximately 30% for acid-fast stain and

tivity of all three of these tests.35,36,38 approximately 60% for PCR or culture.44,45

Listeria meningitis may present with symptoms and

CSF parameters that mimic viral meningitis. Intracere-

Aseptic meningitis: not synonymous with

bral abscess may also present in a similar manner, with

viral meningitis

or without focal neurological signs.46 Leptospirosis can

Viral meningitis is most commonly caused by the entero- cause acute meningitis; this diagnosis should be consid-

viruses and is self-limiting, although HSV or VZV menin- ered in those who work with animals or who have had

gitis may warrant antiviral therapy in some exposure to faecally contaminated water.47 Meningitis

circumstances.39,40 HIV is an important yet overlooked can be a manifestation of secondary syphilis.1 In a

cause of viral meningitis. The yield of testing for HIV was patient with CSF eosinophilia of ≥10% or peripheral

shown in one report from North Carolina where stored blood eosinophilia, and with recent travel to Southeast

CSF samples from 57 patients who had presented with Asia or the Pacific region, eosinophilic meningitis (most

non-bacterial meningitis were retrospectively tested for commonly caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis) should

1298 Internal Medicine Journal 48 (2018) 1294–1307

© 2018 Royal Australasian College of Physicians

Meningitis in adults

be considered, particularly if the patient gives a history Early consultation with an infectious diseases physi-

of consumption of fresh vegetables or raw snails. Eosino- cian may improve patient outcomes. In one study,

phils can be misidentified as neutrophils if CSF analysis patients with bacterial meningitis who were managed by

is automated, and thus the laboratory should be alerted infectious diseases physicians were significantly more

if this diagnosis is suspected.48 likely to commence antibiotics within 1 h of presentation

and to receive dexamethasone, and were less likely to

experience treatment delays while awaiting

Management

neuroimaging.5

Immediate priorities, before and on arrival to

hospital Empirical therapy

In bacterial meningitis, prompt treatment is life-saving. Most guidelines recommend dexamethasone plus ceftri-

For patients who present to primary care with suspected axone in the initial empirical treatment of community-

meningococcal disease, pre-hospital treatment with par- acquired bacterial meningitis in adults. While the North

enteral benzylpenicillin or ceftriaxone has been advo- American guideline13 recommends the addition of van-

cated.19,31 Intuitively, the benefits of early antibiotic comycin for all patients, guidelines from Australia,31 the

administration seem clear. However, evidence that this UK19 and Europe14 recommend the addition of vanco-

practice improves outcomes is lacking; observational mycin only for patients who are more likely to have

studies have reported that pretreated patients have pneumococcal meningitis or who have personal or epi-

worse outcomes, although this may be because those demiological risk factors for being infected with a

who were pretreated had more severe disease than those S. pneumoniae strain with reduced susceptibility to ceftri-

who were not.49 An alternative hypothesis for this find- axone. In Australia, the inclusion of vancomycin in the

ing is that rapid bacteriolysis following antibiotic admin- initial empirical regimen is recommended for patients

istration may precipitate shock due to the release of with known or suspected otitis media or sinusitis, for

meningococcal endotoxins; this could be deleterious if it those who have been treated with beta-lactam antibi-

occurs in the community, rather than in the hospital otics recently and for those with Gram-positive cocci in

where there is greater access to fluid resuscitation and the CSF or with a positive pneumococcal BAT.31 An

inotropic support. This theory is also unproven.49 Given anti-Listeria agent should also be added for patients with

this lack of evidence, the role of pre-hospital antibiotics risk factors for Listeria meningitis (age ≥ 50, long-term

remains unclear; they should be given to patients who use of glucocorticoids or other immunosuppressive

present to rural or remote practices and face a prolonged drugs, diabetes, alcoholism, cirrhosis, end-stage renal

transport time to a secondary care facility.31 failure, malignancy, HIV infection and organ transplan-

On arrival at hospital, the patient should be placed in tation).10 Benzylpenicillin and trimethoprim/sulfameth-

droplet precautions to prevent potential nosocomial oxazole are active against L. monocytogenes, but

transmission of meningococcal infection and resuscitated ceftriaxone and vancomycin are not. An approach to ini-

as required.8 Blood and, ideally, CSF cultures should be tial investigation and management is summarised in

quickly obtained, following which dexamethasone and Figure 1, and an approach to empirical therapy is sum-

antibiotics should be given, aiming for administration marised in Table 3.

within 1 h of admission.4 The importance of timely ther-

apy has been demonstrated in multiple studies, with one

Dexamethasone

study showing an increase in mortality of 13%4 and

another showing an increase in mortality and disability Dexamethasone reduces cerebral inflammation, oedema

of 30%50 for every hour that treatment is delayed. In and ICP in experimental models of bacterial meningitis.51

most cases, CSF should be obtained prior to the com- In a meta-analysis of clinical trials, early treatment with

mencement of antimicrobials, although in certain situa- dexamethasone reduced mortality rates in patients with

tions, this introduces an unacceptable delay to pneumococcal meningitis from 36% to 30%, as well as

treatment; these situations include the need to obtain a significantly reducing hearing loss and other neurological

CT prior to LP, a clinical contraindication to LP, multiple sequelae.2 These beneficial effects were not seen in a sub-

failed attempts at this procedure or in patients with sep- group analysis of patients with meningococcal meningitis,

tic shock.19 In these cases, dexamethasone and antibi- although dexamethasone treatment is unlikely to be

otics should be given once blood cultures have been harmful in this group if given.14 Guidelines recommend

drawn, and CSF should be obtained at the earliest possi- the empirical use of 10 mg dexamethasone intravenously

ble opportunity. (IV) every 6 h in patients with bacterial

Internal Medicine Journal 48 (2018) 1294–1307 1299

© 2018 Royal Australasian College of Physicians

Young & Thomas

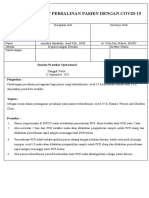

Use droplet precautions

Urgently address airway or

circulatory compromise

Draw bloods including blood

cultures

Is there an indication for CT Yes 10mg dexamethasone IV q6h and

head prior to LP? (Table 1) antibiotics (Table 3)

No

Obtain CT head

Is there a clinical Yes 10mg dexamethasone IV q6h and

†

contraindication to LP? antibiotics (Table 3)

No

Perform LP Perform LP as soon as safely possible

10mg dexamethasone IV q6h Tailor to directed therapy once

and antibiotics (Table 3) pathogen identified

Figure 1 Initial investigation and management of adults with suspected bacterial meningitis. †Anti-coagulation, anti-platelet therapy other than aspi-

rin, dual anti-platelet therapy, clinical evidence of disseminated intravascular coagulation, local infection or loss of skin integrity at puncture site, raised

intracranial pressure on computed tomography (CT) head if performed. IV, intravenous; LP, lumbar puncture.

meningitis,13,14,19,31 although it would be reasonable to started after the first antibiotic dose, although some

omit this if the clinical presentation strongly suggests experts recommend that it can be started up to 4 h after

meningococcal meningitis. Other corticosteroids should this.14 There have been theoretical concerns that dexa-

not be used due to their inferior CNS penetration.13 Dexa- methasone may decrease antibiotic penetration into the

methasone should be started before or at the same time CNS by reducing meningeal inflammation; however, one

as the first antibiotic dose in order to attenuate cerebral study demonstrated adequate CSF vancomycin concen-

inflammation caused by antibiotic-mediated bacterioly- trations despite treatment with dexamethasone.52 For

sis.2 It is unclear if dexamethasone has any benefit when unclear reasons, the beneficial effects of dexamethasone

1300 Internal Medicine Journal 48 (2018) 1294–1307

© 2018 Royal Australasian College of Physicians

Meningitis in adults

Table 3 Empirical therapy for adults with suspected bacterial meningitis in Australia

First-line therapy Therapy for patients with Therapy for patients with severe T

immediate cell-mediated reaction to penicillins†

penicillin hypersensitivity

Dexamethasone‡ PLUS Dexamethasone‡ Dexamethasone‡

ceftriaxone§ PLUS ceftriaxone§ PLUS moxifloxacin¶

If higher likelihood of pneumococcal Add vancomycin‡‡ Add vancomycin‡‡ Add vancomycin‡‡

meningitis††, or recent β-lactam use

If risk factors for Listeria meningitis Add benzylpenicillin§§ Add trimethoprim/ Add trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole¶¶

sulfamethoxazole¶¶

†For example, toxic epidermal necrolysis or Stevens–Johnson syndrome. ‡Dexamethasone dosed at 10 mg IV q6hr. §Ceftriaxone dosed at 2 g IV

q12hr. ¶Moxifloxacin dosed at 400 mg IV q24hr. ††Known or suspected otitis media or sinusitis, Gram-positive cocci in the CSF, positive pneumococcal

BAT. ‡‡Vancomycin IV dosed to achieve a trough concentration of 15–20 mg/L. §§Benzylpenicillin dosed at 2.4 g IV q4h. ¶¶Trimethoprim/sulfamethox-

azole dosed at 160/800 mg IV q6hr. BAT, bacterial antigen testing; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; IV, intravenous.

seem confined to high-income countries, which is unfor- ceftriaxone is not well established. For these patients,

tunate given that bacterial meningitis is many times more moxifloxacin can be used as an alternative empirical

prevalent in the developing world.2 therapy, or ciprofloxacin plus vancomycin if moxifloxa-

If pneumococcal meningitis is diagnosed, treatment cin is not available.

with dexamethasone should be continued for 4 days. S. pneumoniae isolates were uniformly susceptible to

Dexamethasone can be stopped if meningococcal menin- penicillin and ceftriaxone prior to the 1970s. However,

gitis is diagnosed.14 Dexamethasone should also be since then, the proportion of strains with a modestly

stopped if Listeria meningitis is diagnosed as there is evi- increased minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) to

dence that patients who receive this treatment have a these antibiotics has steadily risen. Fortunately, this has

higher mortality rate than those who do not.53 not had major effects on the treatment of pneumococcal

infections outside of the CNS as concentrations exceed-

ing these modestly elevated MIC are readily achieved in

Antibiotics serum and tissues by high-dose IV administration. In

contrast, the concentration of either penicillin or ceftri-

Because almost all strains of N. meningitidis and many

axone that is achieved in the CSF is many times lower

strains of S. pneumoniae are sensitive to ceftriaxone, most

than that in the serum and may be too low to be active

guidelines recommend 2 g ceftriaxone IV every

against the infecting strain of S. pneumoniae.55 MIC

12 h.13,14,19,31 It is important to note that ceftriaxone pro-

breakpoints of penicillin are defined differently for men-

vides no cover for L. monocytogenes.13 In those with IgE- ingitis and non-meningitis infections caused by

mediated allergies to penicillins (including anaphylaxis), S. pneumoniae (Table 4).

ceftriaxone is likely to be safe due to negligible rates of Figure 2A shows the distribution of penicillin MIC for

cross-reactivity between penicillins and third-generation 37 742 isolates of S. pneumoniae,57 and 2B the concentra-

cephalosporins.54 However, in those with severe T cell- tions of penicillin in serum and in CSF during 4 h after

mediated reactions to penicillins, such as toxic epidermal the IV administration of 1.2 g benzylpenicillin.58 In all

necrolysis or Stevens–Johnson syndrome, the safety of patients at 1 h after treatment, and in most patients at 2 h

after treatment, the concentration of penicillin in serum

Table 4 European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

exceeded the MIC of all pneumococcal isolates. In con-

MIC breakpoints of benzylpenicillin and ceftriaxone for treatment of trast, no patient had a CSF penicillin concentration that

S. pneumoniae infections56 exceeded the MIC of all pneumococcal isolates at any

point during the 4 h after administration. However, in all

MIC breakpoint (mg/L)

patients throughout the 4-h period, the concentrations of

Susceptible Resistant penicillin in CSF were >0.06 mg/L. Studies of animals

Benzylpenicillin with pneumococcal meningitis treated with beta-lactam

Meningitis ≤0.06 >0.06 antibiotics, such as penicillin or ceftriaxone, show that

Non-meningitis ≤0.06 >2 maximal bacterial killing is achieved when the CSF con-

Ceftriaxone centrations of the beta-lactam antibiotic exceed the mini-

Meningitis and non-meningitis ≤0.5 >2

mum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of the antibiotic

MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration. for >90% of the treatment interval.62 Because the MIC

Internal Medicine Journal 48 (2018) 1294–1307 1301

© 2018 Royal Australasian College of Physicians

Young & Thomas

Figure 2 (A) Distribution of penicillin minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) for 37 742 S. pneumoniae isolates; black bars represent strains suscep-

tible to penicillin using meningitis criteria (MIC < 0.06 mg/L), and white bars represent strains resistant to penicillin (MIC > 0.06 mg/L).57 (B) Penicillin

concentrations in serum (solid circles and bars) and in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (open circles and dashed bars) in eight patients following a 1.2 g intra-

venous (IV) bolus of benzylpenicillin.58 (C) Distribution of ceftriaxone MIC for 3238 S. pneumoniae isolates; black bars represent strains susceptible to

ceftriaxone (MIC ≤ 0.5 mg/L), and grey bars represent strains with decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone (MIC > 0.5 mg/L).57 (D) Ceftriaxone concen-

trations in serum (solid circles and bars)59 and in CSF (open circles and dashed bars)60,61 in adult patients following a 2 g IV bolus of ceftriaxone.

closely approximates the MBC for most beta-lactam anti- Australia, the addition of vancomycin is recommended

biotics, the presence of antibiotic concentrations greater for patients who are most likely to have pneumococcal

than the MIC throughout each treatment interval is likely meningitis, such as those with known or suspected otitis

to provide maximal bacterial killing. Treatment with ben- media or sinusitis and those who have Gram-positive

zylpenicillin (2.4 g IV every 4 h) is therefore very likely to cocci seen in the CSF analysis or a positive pneumococ-

be effective for patients with pneumococcal meningitis cal BAT.31 Vancomycin should also be added for patients

caused by strains with MIC ≤ 0.06 mg/L but less likely to with risk factors for infection with a S. pneumoniae strain

be effective for patients with meningitis caused by strains with reduced susceptibility to ceftriaxone, such as those

with penicillin MIC > 0.06 mg/L. treated with beta-lactam antibiotics in the last 3 months;

Figure 2C shows the distribution of ceftriaxone MIC recent hospitalisation and residence in a long-term care

for 3238 isolates of S. pneumoniae,57 and Figure 2D shows facility have also been identified as risk factors for a resis-

the concentrations of ceftriaxone in serum59 and in tant strain.63 If pneumococcal meningitis is confirmed,

CSF60,61 during 24 h after the IV administration of 2 g vancomycin should be continued until the ceftriaxone

ceftriaxone. Throughout the 24-h period, the concentra- MIC is available.64 In Australia, in 2012, 10% of

tions of ceftriaxone in serum were consistently higher S. pneumoniae isolates from sterile sites demonstrated

than the MIC of all strains of S. pneumoniae, and the con- decreased susceptibility to penicillin (MIC > 0.06 mg/L),

centrations of ceftriaxone in CSF were consistently ≥1 but only 2% demonstrated decreased susceptibility to

mg/L. Treatment with ceftriaxone (2 g IV every 12 h) is ceftriaxone (MIC > 0.5 mg/L).65 At Auckland City Hospi-

therefore very likely to be effective for the majority of tal in New Zealand during 2017, 35% of S. pneumoniae

patients with pneumococcal meningitis but may be isolates from blood or CSF demonstrated decreased sus-

ineffective in patients with meningitis caused by ceptibility to penicillin, while 11% demonstrated

S. pneumoniae strains with ceftriaxone MIC >2 mg/L. decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone, suggesting that

Because CSF concentrations of ceftriaxone may not be the addition of vancomycin should be routine when

sufficient to treat S. pneumoniae strains with reduced sus- empirically treating patients with meningitis in Auck-

ceptibility to ceftriaxone, the supplementation of initial land.66 Resistance to vancomycin has not yet been

therapy with vancomycin should be considered. In reported for S. pneumoniae.

1302 Internal Medicine Journal 48 (2018) 1294–1307

© 2018 Royal Australasian College of Physicians

Meningitis in adults

Other considerations 2016 and the identification of a penicillin-resistant ser-

ogroup B isolate in 2010, both from Western

Many patients with bacterial meningitis are critically

Australia.69,70 While most guidelines recommend between

unwell and will require support in the intensive care

5 and 7 days of antibiotic therapy for meningococcal

unit. This may include airway support with mechanical

meningitis,13,31,64 experience with 88 patients during a

ventilation, circulatory support with inotropes, medical

very large meningococcal epidemic in New Zealand found

or surgical reduction of raised ICP and medical manage-

that 3 days of benzylpenicillin was effective treatment,

ment of coagulopathy, hyponatraemia and seizures.

strongly suggesting that longer courses are unnecessary.71

Later in the course of meningococcal disease, those with

Dexamethasone can be stopped in patients with con-

purpura fulminans may require debridement or amputa-

firmed meningococcal meningitis.14

tion of necrotic tissues and reconstruction with skin

Patients with meningococcal disease should be placed

grafts or flaps.67 For adults with pneumococcal meningi-

in droplet precautions until 24 h of antibiotic therapy

tis, predisposing conditions, such as otitis media, sinusitis

has been given.8 In cases of suspected or confirmed

or mastoiditis, should be sought and managed in con-

meningococcal disease, public health authorities should

junction with otorhinolaryngology if required.9

be notified and clearance antibiotics administered to

close contacts. Options for non-pregnant persons include

Directed therapy ciprofloxacin (a single 500 mg oral dose) or rifampicin

(600 mg orally twice/day for 2 days); rifampicin should

Once a presumptive microbiological diagnosis has been pro- be avoided in women taking the oral contraceptive pill

vided by Gram stain or confirmed by culture or PCR, fur- or in patients for whom there are other important drug

ther therapy can be directed at the identified pathogen.13 interactions. Ceftriaxone (a single intramuscular dose of

Streptococcus pneumoniae 250 mg) is the preferred option for pregnant women.

Penicillin does not adequately eradicate nasopharyngeal

For pneumococcal meningitis, a 10–14-day course of IV carriage of meningococci; thus, clearance antibiotics are

therapy should be completed, with dexamethasone given also required for the index case unless at least one dose

during the first 4 days.13 In patients infected with of ceftriaxone has been given during treatment. Clear-

ceftriaxone-susceptible strains, vancomycin can be discon- ance antibiotics should be initiated as soon as possible,

tinued and treatment continued with 2 g ceftriaxone IV ideally on the day of diagnosis, but should still be given

every 12 h. If the isolate is penicillin-susceptible, clinicians up to 14 days following exposure. Vaccination for close

may consider changing to 2.4 g benzylpenicillin IV every contacts is also recommended if the infecting organism is

4 h to avoid continuing with an unnecessarily broad- in a vaccine-preventable serogroup. However, serotyping

spectrum agent.56 If the isolate is ceftriaxone-intermediate usually requires referral of the specimen to a reference

or -resistant, options include continuing ceftriaxone and laboratory, and results may not be available within the

vancomycin if the patient has responded well to initial appropriate timeframe to implement vaccination.8,72

therapy (with consideration of the addition of rifampicin)

or changing to 400 mg moxifloxacin IV every 24 h.31,68 Listeria monocytogenes

Survivors have a 5% risk of recurrence of pneumococcal A dose of 2.4 g benzylpenicillin IV every 4 h (or 2 g amoxi-

meningitis, and thus pneumococcal vaccination is recom- cillin IV every 4 h) is the treatment of choice for meningitis

mended; this is particularly important for those with a caused by L. monocytogenes. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxa-

predisposing immunodeficiency or CSF leak.14 zole can be used for patients with penicillin allergy.13

The addition of gentamicin appears to reduce mortality,

Neisseria meningitidis

although this has not been proven in randomised tri-

A dose of 1.8 g benzylpenicillin IV every 4 h should be als.53,64 Optimal treatment duration is unknown, but IV

used for the treatment of meningococcal meningitis in antibiotics are generally continued for at least 21 days.13

Australia and New Zealand.31 Ceftriaxone can be used for Dexamethasone should be discontinued immediately if

patients with immediate penicillin hypersensitivity54 and L. monocytogenes has been identified, because of the worse

moxifloxacin or ciprofloxacin used for patients with outcome in patients who receive dexamethasone.53

severe T cell-mediated reactions to penicillins.13,31 While

Viral meningitis

strains with intermediate susceptibility to penicillin are

increasingly detected, high doses of penicillin are clinically Dexamethasone and antibiotics can be discontinued if

effective.69 Although frank resistance to penicillin remains CSF parameters are consistent with viral meningitis, pro-

rare, vigilance is required given the emergence of a vided the clinical suspicion for bacterial meningitis is

penicillin-resistant clade of N. meningitidis serogroup W in low. Enteroviral meningitis is self-limiting and requires

Internal Medicine Journal 48 (2018) 1294–1307 1303

© 2018 Royal Australasian College of Physicians

Young & Thomas

only supportive care. HSV meningitis is also self-limiting administered at 12 months of age.74 In New Zealand,

in immunocompetent patients; symptomatic treatment meningococcal serogroups B and C are of the most impor-

alone is reasonable, although 7–10 days of antiviral tance, but no meningococcal vaccines are included in the

treatment (with acyclovir, valacyclovir or famciclovir) New Zealand immunisation schedule.72 Vaccination against

has been shown to improve neurological outcomes in serogroups A, C, W and Y is recommended for people at

immunocompromised hosts.39 It is vital to recognise that high risk of meningococcal disease, including patients with

HSV encephalitis (usually caused by HSV-1) is a distinct terminal complement deficiencies or asplenia, those with

entity from HSV meningitis (usually caused by HSV-2); HIV infection, military recruits and some travellers, such as

in HSV encephalitis, treatment with IV acyclovir is criti- those whose destination is the ‘meningitis belt’ in sub-

cal in reducing mortality and disability.40 The optimal Saharan Africa. For pilgrims to the Hajj in Saudi Arabia,

treatment of VZV meningitis is unknown, although most quadrivalent meningococcal vaccination is a requirement

clinicians would give antivirals unless the patient was of entry.72 Producing effective vaccines against meningo-

already improving without therapy.40 Meningitis caused coccal serogroup B has proven difficult due to its poorly

by acute HIV infection requires ongoing follow up and immunogenic capsule. In New Zealand, between 2004 and

management from an experienced specialist. 2008, the MeNZB vaccine was offered to children and ado-

lescents and had a modest effect on the nationwide menin-

gococcal epidemic; however, this vaccine was targeted

Deteriorating patients

against the epidemic strain alone and produced only a rela-

Neuroimaging is indicated in patients who fail to tively weak and short-lived immune response.72 Advances

improve or in whom neurological abnormalities or sei- have occurred in serogroup B vaccine development, and a

zures develop, to evaluate for hydrocephalus, venous vaccine (Bexsero, GlaxoSmithKline) that is immunogenic

sinus thrombosis, subdural empyema or intracerebral against an estimated 76% of group B meningococcal strains

abscess. These complications occur most commonly in is now available in Australia for private purchase. The

patients with pneumococcal meningitis.67 Repeat LP duration of protection remains unknown.74

should be considered in those who fail to improve after

48 h of treatment and who have unremarkable neuro-

imaging; this is particularly important for patients with Conclusion

meningitis caused by a strain of S. pneumoniae with

The likelihood of confirming the responsible pathogen

reduced susceptibility to ceftriaxone.13

in cases of community-acquired bacterial meningitis

has been improved by newer techniques, such as mul-

Primary prevention tiplex PCR. However, a thorough understanding of the

interpretation of basic CSF parameters, as well as the

Childhood vaccination against Haemophilus influenzae sero-

caveats of relying on CSF parameters alone to exclude

type b has led to the near-complete elimination of menin-

bacterial meningitis, is required to accurately diagnose

gitis caused by this pathogen in countries with adequate

this often terrifying condition. Clinicians should collect

vaccination coverage.72 Pneumococcal vaccination is

blood cultures and CSF and initiate treatment within

incorporated into the immunisation schedules of both

1 h of making a presumptive clinical diagnosis of bacte-

Australia and New Zealand; vaccination has reduced the

rial meningitis. They should be aware of the worse out-

rates of pneumococcal meningitis in children and adults,

comes that occur when neuroimaging unnecessarily

albeit with a rise in the proportion of cases caused by

delays LP and the initiation of treatment. Prompt ther-

serotypes not included in vaccines.72 No effective vaccines

apy with dexamethasone plus ceftriaxone, with the

have been developed against L. monocytogenes.

addition of vancomycin and/or benzylpenicillin when

In Australia, most cases of meningococcal disease are

indicated, improves the chance of a positive outcome

caused by serogroups W, B and Y, which were responsible

for patients affected by this devastating and disabling

for 43%, 36% and 16% of cases in 2016 respectively.73

disease.

Serogroup C disease has become very rare since the conju-

gate meningococcal C vaccine was introduced to the

Australian immunisation schedule in 2003, with the excep-

Acknowledgements

tion of an outbreak of serogroup C disease in 2017 among

men who have sex with men in Melbourne.74,75 In 2018, Dr Stephen Ritchie (Department of Infectious Diseases,

the serogroup C vaccine was replaced in the Australian Auckland City Hospital and Department of Molecular

immunisation schedule by a quadrivalent conjugate vac- Medicine and Pathology, University of Auckland) kindly

cine against serogroups A, C, W and Y, which is reviewed the manuscript and gave helpful advice.

1304 Internal Medicine Journal 48 (2018) 1294–1307

© 2018 Royal Australasian College of Physicians

Meningitis in adults

References 12 Hasbun R, Abrahams J, Jekel J, as an indicator for bacterial meningitis.

Quagliarello V. Computed tomography Am J Emerg Med 2014; 32: 263–6.

1 Tunkel AR, van de Beek D, Scheld W. of the head before lumbar puncture in 23 Seehusen D, Reeves M, Fomin D.

Acute meningitis. In: Bennett J, Dolin R adults with suspected meningitis. N Engl Cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Am Fam

and Blaser M, eds. Principles and Practice J Med 2001; 345: 1727–33. Physician 2003; 68: 1103–8.

of Infectious Diseases, 8th edn. 13 Tunkel AR, Hartman BJ, Kaplan SL, 24 Hase R, Hosokawa N, Yaegashi M,

Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders; 2015; Kaufman BA, Roos KL, Scheld WM Muranaka K. Bacterial meningitis in the

1097–137. et al. Practice guidelines for the absence of cerebrospinal fluid

2 Brouwer MC, McIntyre P, Prasad K, van management of bacterial meningitis. pleocytosis: a case report and review of

de Beek D. Corticosteroids for acute Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39: 1267–84. the literature. Can J Infect Dis Med

bacterial meningitis. Cochrane Database 14 van de Beek D, Cabellos C, Dzupova O, Microbiol 2014; 25: 249–51.

Syst Rev 2015: CD004405. Esposito S, Klein M, Kloek AT et al. 25 Feigin RD, Shackelford PG. Value of

3 Strelow VL, Vidal JE. ESCMID guideline: diagnosis and repeat lumbar puncture in the

Invasive meningococcal disease. treatment of acute bacterial meningitis. differential diagnosis of meningitis. N

Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2013; 71: 653–8. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016; 22: S37–62. Engl J Med 1973; 289: 571–4.

4 Glimaker M, Johansson B, Grindborg O, 15 Glimaker M, Johansson B, Bell M, 26 Kaewpoowat Q, Salazar L, Aguilera E,

Bottai M, Lindquist L, Sjolin J. Adult Ericsson M, Blackberg J, Brink M et al. Wootton SH, Hasbun R. Herpes simplex

bacterial meningitis: earlier treatment Early lumbar puncture in adult bacterial and varicella zoster CNS infections:

and improved outcome following meningitis--rationale for revised clinical presentations, treatments

guideline revision promoting prompt guidelines. Scand J Infect Dis 2013; 45: and outcomes. Infection 2016; 44:

lumbar puncture. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 657–63. 337–45.

60: 1162–9. 16 Larsen L, Poulsen FR, Nielsen TH, 27 Philip N, William T, John D. Diagnosis

5 Grindborg O, Naucler P, Sjolin J, Nordstrom CH, Schulz MK, of tuberculous meningitis: challenges

Glimaker M. Adult bacterial Andersen AB. Use of intracranial and promises. Malays J Pathol 2015;

meningitis-a quality registry pressure monitoring in bacterial 37: 1–9.

study: earlier treatment and meningitis: a 10-year follow up on 28 Hegen H, Auer M, Deisenhammer F.

favourable outcome if initial outcome and intracranial pressure Serum glucose adjusted cut-off values

management by infectious diseases versus head CT scans. Infect Dis (Lond) for normal cerebrospinal fluid/serum

physicians. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015; 2017; 49: 356–64. glucose ratio: implications for clinical

21: 560–6. 17 Glimaker M, Sjolin J, Akesson S, practice. Clin Chem Lab Med 2014; 52:

6 Proulx N, Frechette D, Toye B, Chan J, Naucler P. Lumbar puncture performed 1335–40.

Kravcik S. Delays in the administration promptly or after neuroimaging in 29 Spanos A, Harrell FE Jr, Durack DT.

of antibiotics are associated with acute bacterial meningitis in adults: a Differential diagnosis of acute

mortality from adult acute bacterial prospective national cohort study meningitis. An analysis of the predictive

meningitis. QJM 2005; 98: 291–8. evaluating different guidelines. Clin value of initial observations. JAMA

7 van de Beek D, de Gans J, Spanjaard L, Infect Dis 2018; 66: 321–8. 1989; 262: 2700–7.

Weisfelt M, Reitsma JB, Vermeulen M. 18 Attia J, Hatala R, Cook D, Wong J. 30 Fitch MT, van de Beek D. Emergency

Clinical features and prognostic factors Does this adult patient have acute diagnosis and treatment of adult

in adults with bacterial meningitis. N meningitis? JAMA 1999; 282: meningitis. Lancet Infect Dis 2007; 7:

Engl J Med 2004; 351: 1849–59. 175–81. 191–200.

8 Australian Government Department of 19 McGill F, Heyderman RS, Michael BD, 31 Antibiotic Expert Groups. Therapeutic

Health. Invasive Meningococcal Disease. Defres S, Beeching NJ, Borrow R et al. Guidelines: Antibiotic. Version 15.

Canberra, Australia: Communicable The UKjoint specialist societies Melbourne, Australia: Therapeutic

Diseases Network Australia; 2017. guideline on the diagnosis and Guidelines Limited; 2014.

9 Mook-Kanamori BB, Geldhoff M, van management of acute meningitis and 32 McBride S, Fulke J, Giles H, Hobbs M,

der Poll T, van de Beek D. Pathogenesis meningococcal sepsis in Suh J, Sathyendran V et al.

and pathophysiology of pneumococcal immunocompetent adults. J Infect 2016; Epidemiology and diagnostic testing for

meningitis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011; 24: 72: 405–38. meningitis in adults as the

557–91. 20 Gray L, Fedorko D. Laboratory meningococcal epidemic declined at

10 Brouwer M, van de Beek D, diagnosis of bacterial meningitis. Clin Middlemore Hospital. N Z Med J 2015;

Heckenberg S, Spanjaard L, de Gans J. Microbiol Rev 1992; 5: 130–45. 128: 17–24.

Community-acquired Listeria 21 Pappas PG, Perfect JR, Cloud GA, 33 Le Monnier A, Abachin E, Beretti JL,

monocytogenes meningitis in adults. Clin Larsen RA, Pankey GA, Lancaster DJ Berche P, Kayal S. Diagnosis of Listeria

Infect Dis 2006; 43: 1233–8. et al. Cryptococcosis in human monocytogenes meningoencephalitis by

11 Michael B, Menezes BF, Cunniffe J, immunodeficiency virus-negative real-time PCR for the hly gene. J Clin

Miller A, Kneen R, Francis G et al. patients in the era of effective azole Microbiol 2011; 49: 3917–23.

Effect of delayed lumbar punctures on therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 33: 690–9. 34 Brink M, Welinder-Olsson C,

the diagnosis of acute bacterial 22 Tamune H, Takeya H, Suzuki W, Hagberg L. Time window for positive

meningitis in adults. Emerg Med J 2010; Tagashira Y, Kuki T, Honda H et al. cerebrospinal fluid broad-range

27: 433–8. Cerebrospinal fluid/blood glucose ratio bacterial PCR and Streptococcus

Internal Medicine Journal 48 (2018) 1294–1307 1305

© 2018 Royal Australasian College of Physicians

Young & Thomas

pneumoniae immunochromatographic study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014; 20: antimicrobial susceptibility in an era of

test in acute bacterial meningitis. Infect O600–8. resistance. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 48:

Dis (Lond) 2015; 47: 869–77. 45 Nhu NT, Heemskerk D, Thu do DA, 1596–600.

35 Sakushima K, Hayashino Y, Chau TT, Mai NT, Nghia HD et al. 56 European Committee on Antimicrobial

Kawaguchi T, Jackson JL, Fukuhara S. Evaluation of GeneXpert MTB/RIF for Susceptibility Testing (homepage on the

Diagnostic accuracy of cerebrospinal diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. J Internet). Breakpoint tables for

fluid lactate for differentiating bacterial Clin Microbiol 2014; 52: 226–33. interpretation of MICs and zone

meningitis from aseptic meningitis: a 46 Prasad K, Kumar A, Gupta PK, diameters. Version 8.0. 2018. [cited

meta-analysis. J Infect 2011; 62: Singhal T. Third generation 20 Mar 2018]. Available from URL:

255–62. cephalosporins versus conventional http://www.eucast.org/clinical_

36 Vikse J, Henry BM, Roy J, antibiotics for treating acute bacterial breakpoints/

Ramakrishnan PK, Tomaszewski KA, meningitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 57 European Committee on Antimicrobial

Walocha JA. The role of serum 2007: CD001832. Susceptibility Testing. Antimicrobial

procalcitonin in the diagnosis of 47 Wang N, Han YH, Sung JY, Lee WS, wild type distributions of

bacterial meningitis in adults: a Ou TY. Atypical leptospirosis: an microorganisms. 2018. [cited 2018 Feb

systematic review and meta-analysis. Int overlooked cause of aseptic meningitis. 2]. Available from URL: https://mic.

J Infect Dis 2015; 38: 68–76. BMC Res Notes 2016; 9: 154. eucast.org/Eucast2/

37 Markanday A. Acute phase reactants in 48 Ramirez-Avila L, Slome S, Schuster FL, 58 Schoth PE, Wolters EC. Penicillin

infections: evidence-based review and a Gavali S, Schantz PM, Sejvar J et al. concentrations in serum and CSF

guide for clinicians. Open Forum Infect Eosinophilic meningitis due to during high-dose intravenous treatment

Dis 2015; 2: ofv098. Angiostrongylus and Gnathostoma for neurosyphilis. Neurology 1987; 37:

38 Ray P, Badarou-Acossi G, Viallon A, species. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 48: 322–7. 1214–6.

Boutoille D, Arthaud M, Trystram D 49 Harnden A, Ninis N, Thompson M, 59 Patel IH, Chen S, Parsonnet M,

et al. Accuracy of the cerebrospinal fluid Perera R, Levin M, Mant D et al. Hackman MR, Brooks MA, Konikoff J

results to differentiate bacterial from Parenteral penicillin for children with et al. Pharmacokinetics of ceftriaxone in

non bacterial meningitis, in case of meningococcal disease before hospital humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother

negative Gram-stained smear. admission: case-control study. BMJ 1981; 20: 634–41.

Am J Emerg Med 2007; 25: 179–84. 2006; 332: 1295–8. 60 Chandrasekar PH, Rolston KV,

39 Noska A, Kyrillos R, Hansen G, 50 Koster-Rasmussen R, Korshin A, Smith BR, LeFrock JL. Diffusion of

Hirigoyen D, Williams DN. The role of Meyer CN. Antibiotic treatment delay ceftriaxone into the cerebrospinal fluid

antiviral therapy in and outcome in acute bacterial of adults. J Antimicrob Chemother 1984;

immunocompromised patients with meningitis. J Infect 2008; 57: 449–54. 14: 427–30.

herpes simplex virus meningitis. Clin 51 Borchorst S, Moller K. The role of 61 Cabellos C, Viladrich PF, Verdaguer R,

Infect Dis 2015; 60: 237–42. dexamethasone in the treatment of Pallares R, Liñares J, Gudiol F. A single

40 Logan SA, MacMahon E. Viral bacterial meningitis – a systematic daily dose of ceftriaxone for bacterial

meningitis. BMJ 2008; 336: 36–40. review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2012; 56: meningitis in adults: experience with

41 Hanson K, Reckleff J, Hicks L, 1210–21. 84 patients and review of the

Castellano C, Hicks C. Unsuspected HIV 52 Ricard JD, Wolff M, Lacherade JC, literature. Clin Infect Dis 1995; 20:

infection in patients presenting with Mourvillier B, Hidri N, Barnaud G et al. 1164–8.

acute meningitis. Clin Infect Dis 2008; Levels of vancomycin in cerebrospinal 62 Lutsar I, McCracken GH Jr,

47: 433–4. fluid of adult patients receiving Friedland IR. Antibiotic

42 Thomas M, Sasadeusz J. Neurological adjunctive corticosteroids to treat pharmacodynamics in cerebrospinal

infections. In: Yung A, Spelman D, pneumococcal meningitis: a prospective fluid. Clin Infect Dis 1998; 27: 1117–29.

Street A, McCormack J, Sorrell T and multicenter observational study. Clin 63 Vanderkooi OG, Low DE, Green K,

Johnson P, eds. Infectious Diseases: A Infect Dis 2007; 44: 250–5. Powis JE, McGeer A. Predicting

Clinical Approach, 3rd edn. Melbourne, 53 Charlier C, Perrodeau É, Leclercq A, antimicrobial resistance in invasive

Australia: IP Communications; 2010; Cazenave B, Pilmis B, Henry B et al. pneumococcal infections. Clin Infect Dis

246–60. Clinical features and prognostic factors 2005; 40: 1288–97.

43 Darras-Joly C, Chevret S, Wolff M, of listeriosis: the MONALISA national 64 van de Beek D, Brouwer MC,

Matheron S, Longuet P, Casalino E et al. prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Thwaites GE, Tunkel AR. Advances in

Cryptococcus neoformans infection in Dis 2017; 17: 510–9. treatment of bacterial meningitis. The

France: epidemiologic features of and 54 Campagna JD, Bond MC, Lancet 2012; 380: 1693–702.

early prognostic parameters for Schabelman E, Hayes BD. The use of 65 Toms C, de Kluyver R. Invasive

76 patients who were infected with cephalosporins in penicillin-allergic pneumococcal disease in Australia 2011

human immunodeficiency virus. Clin patients: a literature review. J Emerg and 2012. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep 2016;

Infect Dis 1996; 23: 369–76. Med 2012; 42: 612–20. 40: E267–84.

44 Erdem H, Ozturk-Engin D, Elaldi N, 55 Weinstein MP, Klugman KP, Jones RN. 66 LabPLUS. Antimicrobial susceptibility

Gulsun S, Sengoz G, Crisan A et al. The Rationale for revised penicillin test results for Gram-positive isolates

microbiological diagnosis of tuberculous susceptibility breakpoints versus recovered from clinical specimens.

meningitis: results of Haydarpasa-1 Streptococcus pneumoniae: coping with Auckland, New Zealand: LabPLUS,

1306 Internal Medicine Journal 48 (2018) 1294–1307

© 2018 Royal Australasian College of Physicians

Meningitis in adults

2018 [cited 2018 Jun 25]. Available 70 Mowlaboccus S, Jolley KA, Bray JE, Available from URL: http://www9.health.

from URL: http://www.labplus.co.nz/ Pang S, Lee YT, Bew JD et al. Clonal gov.au/cda/source/pub_menin.cfm

assets/Uploads/2017-Gram-Positive- expansion of new penicillin-resistant 74 National Centre for Immunisation

Antimicrobial-Report.pdf clade of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup Research and Surveillance.

67 van de Beek D, de Gans J, Tunkel AR, W clonal complex 11, Australia. Emerg Meningococcal vaccines for Australians.

Wijdicks EF. Community-acquired Infect Dis 2017; 23: 1364–7. 2018 [cited 2018 Feb 4]. Available from

bacterial meningitis in adults. N Engl J 71 Briggs S, Ellis-Pegler R, Roberts S, URL: http://www.ncirs.edu.au/assets/

Med 2006; 354: 44–53. Thomas M, Woodhouse A. Short course provider_resources/fact-sheets/

68 Weisfelt M, de Gans J, van de Beek D. intravenous benzylpenicillin treatment meningococcal-Vaccine-fact-sheet.pdf

Bacterial meningitis: a review of of adults with meningococcal disease. 75 Department of Health and Human

effective pharmacotherapy. Expert Opin Intern Med J 2004; 34: 383–7. Services. Outbreak of invasive

Pharmacother 2007; 8: 1493–504. 72 Ministry of Health. Immunisation meningococcal C disease in men who

69 Abeysuriya SD, Speers DJ, Gardiner J, Handbook 2017. Wellington, have sex with men (MSM). 2017 [cited

Murray RJ. Penicillin-resistant Neisseria New Zealand: Ministry of Health; 2017. 2018 Jun 26]. Available from URL:

meningitidis bacteraemia, Kimberley 73 Australian Government Department of https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/about/

region, March 2010. Commun Dis Intell Q Health. Invasive meningococcal disease news-and-events/healthalerts/alert-

Rep 2010; 34: 342–4. public dataset. 2017 [cited 2018 Jun 26]. meningococcal-c-december-2017

Internal Medicine Journal 48 (2018) 1294–1307 1307

© 2018 Royal Australasian College of Physicians

You might also like

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- StreptococciDocument10 pagesStreptococciGea MarieNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Case StudyDocument25 pagesCase StudybomcorNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5810)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Vaksin DengueDocument8 pagesVaksin DengueclaudiaNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Trauma BuliDocument18 pagesTrauma BuliclaudiaNo ratings yet

- HipokalemiaDocument12 pagesHipokalemiaclaudiaNo ratings yet

- Sop Persalinan CovidDocument2 pagesSop Persalinan CovidclaudiaNo ratings yet

- Meaningfull WorkDocument11 pagesMeaningfull WorkclaudiaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 1 Motivation, Competence and WorkloadDocument10 pagesJurnal 1 Motivation, Competence and WorkloadclaudiaNo ratings yet

- Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: Evaluation of Its Provocative Clinical TestsDocument4 pagesCarpal Tunnel Syndrome: Evaluation of Its Provocative Clinical TestsclaudiaNo ratings yet

- Carpal Tunnel SyndromeDocument7 pagesCarpal Tunnel Syndromeclaudia100% (1)

- HipokalemiaDocument12 pagesHipokalemiaclaudiaNo ratings yet

- Trauma Sal KemihDocument70 pagesTrauma Sal KemihclaudiaNo ratings yet

- Acute Bacterial MeningitisDocument15 pagesAcute Bacterial MeningitisOana StefanNo ratings yet

- CPM 10th Ed Community Acquired PneumoniaDocument23 pagesCPM 10th Ed Community Acquired PneumoniaJan Mikhail FrascoNo ratings yet

- Estafilo y EstreptoDocument75 pagesEstafilo y Estreptosalma isabela villadiego garciaNo ratings yet

- NIP FOR SLDocument118 pagesNIP FOR SLMyrel Cedron TucioNo ratings yet

- STREPTOCOCCUSDocument6 pagesSTREPTOCOCCUSValeria Torres olarteNo ratings yet

- Bacteriología Sistemática - NeumococoDocument2 pagesBacteriología Sistemática - NeumococoBrayan FloresNo ratings yet

- Microbiology and Parasitology1Document249 pagesMicrobiology and Parasitology1Keshi Wo100% (3)

- Manual de Laboratorio para La IDentificacion y Prueba de Susceptibilidad A Los Antimicrobianos de Patogenos BacterianosDocument410 pagesManual de Laboratorio para La IDentificacion y Prueba de Susceptibilidad A Los Antimicrobianos de Patogenos BacterianosSebastian AldamaNo ratings yet

- BRANDON NeumococoDocument11 pagesBRANDON NeumococoBrandon GarciaNo ratings yet

- Physical Education 12 Pneumonia: To Be Reported By: Alawi, Lhamiah M. Casano, Diana Elizabeth C. Kinoshita, Ryou GDocument21 pagesPhysical Education 12 Pneumonia: To Be Reported By: Alawi, Lhamiah M. Casano, Diana Elizabeth C. Kinoshita, Ryou GRyou KinoshitaNo ratings yet

- Tarjetas de MicrobiologíaDocument65 pagesTarjetas de MicrobiologíaAna Karen CoronadoNo ratings yet

- Tema 6a. Mecanismos de Tranferencia Genética en BacteriasDocument43 pagesTema 6a. Mecanismos de Tranferencia Genética en Bacteriasfda.narvaezNo ratings yet

- 8.queratitis Ulcerativa Infecciosa BacterianaDocument49 pages8.queratitis Ulcerativa Infecciosa BacterianaOscar Padilla NavarroNo ratings yet

- Prof. Dr. Dr. Hinky Hindra Irawan Satari, Sp.A (K), M.TropPaed - The Role of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines (PCVS) in InfantsDocument38 pagesProf. Dr. Dr. Hinky Hindra Irawan Satari, Sp.A (K), M.TropPaed - The Role of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines (PCVS) in InfantsJayantiNo ratings yet

- 0 - Review of Post Graduate Medical Entrance Examination (PGMEE) (AAA) (PDFDrive - Com) Export PDFDocument39 pages0 - Review of Post Graduate Medical Entrance Examination (PGMEE) (AAA) (PDFDrive - Com) Export PDFAbu ÂwŞmž100% (2)

- Estafilococos y EstreptococoDocument45 pagesEstafilococos y EstreptococoLuis Andrés SalasNo ratings yet

- Dr. Muh. Ilyas - Pneumococ Simpo HajiDocument38 pagesDr. Muh. Ilyas - Pneumococ Simpo HajiMuh SarwinNo ratings yet

- Resumen Unidad 2Document44 pagesResumen Unidad 2AnnerryBarriosNo ratings yet

- Aseptic Meningitis: Exams and TestsDocument8 pagesAseptic Meningitis: Exams and TestsJoylyn Sagon VergaraNo ratings yet

- Neumonia Pediatrics in Review 2008Document16 pagesNeumonia Pediatrics in Review 2008ERNESTO RODRIGUEZ SARASTY.No ratings yet

- Esquema Identificacion StreptococcusDocument4 pagesEsquema Identificacion StreptococcusIngrid paoNo ratings yet

- Cocos Gram Positivos y Negativos - Grupo 3Document40 pagesCocos Gram Positivos y Negativos - Grupo 3KIMBERLY MICHELL SANCHEZ HERNANDEZNo ratings yet

- ESTREPTOCOCOSDocument9 pagesESTREPTOCOCOSSamuel Enrique Hernandez NiñoNo ratings yet

- Normal FloraDocument30 pagesNormal FloraRaul DuranNo ratings yet

- Meningitis Por EstreptococoDocument38 pagesMeningitis Por EstreptococoFranciscoJavierZeidlerAvalosNo ratings yet

- BactériologieDocument53 pagesBactériologieAnonymous SVP382mNo ratings yet

- Batteri Gruppo 1Document42 pagesBatteri Gruppo 1Domenico RicciardiNo ratings yet