Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Russian Theatre Director in Exile

Uploaded by

Gistha WicitaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Russian Theatre Director in Exile

Uploaded by

Gistha WicitaCopyright:

Available Formats

A Russian Theatre Director in

Exile

Dmitry Krymov starts from scratch in New York.

By Helen Shaw

September 29, 2023

Source:

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/persons-of-interest/a-russian-

theatre-director-in-exile

Photographs by Brian Finke for The New Yorker

In October, 2020, the Russian director Dmitry Krymov staged his

own version of Thornton Wilder’s “Our Town” called “Everyone is

Here” for the Moscow theatre School of the Modern Play. At the

time, Krymov didn’t know that Russia would launch a full-scale

invasion of Ukraine, nor that after he signed a public letter criticizing

the war a temporary work trip to Philadelphia would become

permanent exile. Yet “Everyone Is Here,” a video of which floats

around the Internet, still seems very much like a farewell.

A digressive, at times almost witchy reënvisioning of Wilder’s

plainspoken classic from 1938, it begins with a real black cat slipping

through a door before the play’s familiar characters materialize in

swirls of smoke. After a few dreamlike scenes, a man in a cable-knit

sweater and sneakers interrupts the action, claiming to be the director.

Krymov, or rather his avatar (played by Aleksandr Ovchinnikov), tells

the audience that he has been reconstructing a touring American

production of “Our Town” that he saw in Moscow when he was

eighteen. He reminisces about his past, introduces his long-dead

parents, and reënacts spreading an old friend’s ashes, struggling

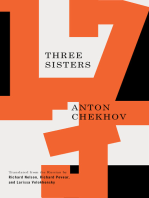

comically with the urn. Eventually Anton Chekhov (two actors in a

trench coat) visits the Sakhalin penal colony. Wilder would never

have recognized it.

Or perhaps he would have. The sixty-eight-year-old Krymov, who

often writes his own adaptations, assumes the American playwright’s

cool-eyed stance toward the inevitability of loss, exhuming his own

past in the process. Krymov frequently drills into the work of a great

artist—Tolstoy, Pushkin, Chekhov—only to break into his own

autobiographical substrate. There’s grief down there, but also a great

deal of comedy. His critically acclaimed productions, full of antic

puppets and rousing folk music and the occasional surprise volleyball

game, recall a circus fairground at night, a wild, inviting darkness

where all the buskers are ghosts. “Everyone is Here” was nominated

for five Golden Mask awards, the Russian equivalent of the Tony, but

once Krymov became persona non grata his name disappeared from

the posters. Officially, at least, no one was there.

And now Krymov is here. Close to a million Russians have emigrated

during the war, flooding into surrounding countries, but unlike some

of the other openly anti-Kremlin superstar directors, who fled to

Europe or Israel, Krymov has come to the United States. This month,

he opens a double bill at La Mama, in New York, called “Big Trip,”

which consists of two programs on different nights: “Pushkin ‘Eugene

Onegin’ in our own words,” a reimagining of an old Krymov piece,

and “Three love stories near the railroad,” a new, tragicomical

triptych that adapts three texts by Eugene O’Neill and Ernest

Hemingway. His first production in New York since a tour of his

expressionist “Opus No. 7,” in 2013, “Big Trip” will also serve as

proof of concept for a newly formed theatre company, a body of

mostly young, mostly American artists called Krymov Lab NYC.

La Mama, in the Bowery, isn’t just Off Broadway, it’s Off Off. In

early September, a few weeks before opening night, Krymov met with

his small company in La Mama’s rehearsal complex on Great Jones

Street, in one of a stack of low, tin-ceilinged rooms where avant-

gardists have been rehearsing for half a century. The actors, who had

been on break for the summer, were trying on costumes for the first

time. They had been rehearsing on and off in the course of a year, and

had held a chaotic series of showings in December. (The night I saw

it, an audience member took a prop and refused to give it back.)

Krymov (Dima to his friends and admirers) is a large man—not tall,

exactly, but bear-on-his-hind-legs imposing—with a wispy, silver

Prince Valiant haircut framing a face that’s moon-calm and smooth.

His glasses, which have an aviator-style bar across the top, make his

eyebrows look perpetually raised. His English is solid and idiomatic,

though he sometimes chooses to speak through an interpreter, his lead

producer Tatyana Khaikin. He’s never as puzzled as he seems to be.

It sometimes takes only a glancing contact with Krymov’s work to

make a fan, even an acolyte. The actors and designers in the Lab have

come together by a number of paths—several are from Yale’s drama

school, where Krymov has guest-taught and directed, and some

trained in Russia, encountering his work in its original habitat. One of

the Lab’s producers and performers, Tim Eliot, for instance, was a

student in the American Repertory Theatre’s Institute for Advanced

Theatre Training, which, when it was still running its graduate

program, conducted a semester in Moscow. There he saw “Opus No.

7,” was “thrilled and awestruck,” and, a decade later, fell into Krymov

and Khaikin’s orbit in New York, when Krymov was teaching at the

New School. (I was in an earlier class of that same A.R.T. program,

but I first saw a Krymov piece in Poland, in 2009, at the Dialog

theatre festival in Wrocław. “Opus No. 7” was a hot ticket, and I

watched it sitting on the floor, crammed partly under someone’s

folding chair.)

During that September rehearsal, several Russian friends and

supporters—including Krymov’s wife, producer, and muse, Inna, and

Isaac Koyfman, a lawyer and theatre aficionado turned president of

Krymov Lab NYC’s newly formed board—were crammed into the

back half of the room. The company’s costume designer, Luna

Gomberg, owlish behind huge glasses, was sewing feverishly next to

a costume rack, on which a black-and-white picture of Inna’s

laughing face hung on one side, with the women’s clothes, and a

mask of Dmitry hung on the other. Inna (tanned, tiny, peripatetic,

brilliant) was chortling about Krymov getting stung by a jellyfish in

France. “The last kiss of summer!” she told me.

You might also like

- SEEP Vol.16 No.3 Fall 1996Document110 pagesSEEP Vol.16 No.3 Fall 1996segalcenterNo ratings yet

- JADT Vol13 n1 Winter2001 Thomson Han Gill Combs PottsDocument104 pagesJADT Vol13 n1 Winter2001 Thomson Han Gill Combs PottssegalcenterNo ratings yet

- The Musical Comedy Films of Grigorii Aleksandrov: Laughing MattersFrom EverandThe Musical Comedy Films of Grigorii Aleksandrov: Laughing MattersNo ratings yet

- Background:: Research On Brief Encounter" A KNEEHIGH ProductionDocument2 pagesBackground:: Research On Brief Encounter" A KNEEHIGH ProductionLiv KhattarNo ratings yet

- American Drama HistoryDocument27 pagesAmerican Drama HistoryFarah MalikNo ratings yet

- SEEP Vol.15 No.2 Summer 1995Document68 pagesSEEP Vol.15 No.2 Summer 1995segalcenterNo ratings yet

- Alexei German Jr. On Dovlatov: "He Was A Sex Symbol, Elvis Presley, A Legend"Document23 pagesAlexei German Jr. On Dovlatov: "He Was A Sex Symbol, Elvis Presley, A Legend"Martincho090909No ratings yet

- Lumiere Showed Several Short Films. They Were All Documentaries and One of ThemDocument2 pagesLumiere Showed Several Short Films. They Were All Documentaries and One of ThemОлінька СтецюкNo ratings yet

- SEEP Vol.17 No.3 Fall 1997Document93 pagesSEEP Vol.17 No.3 Fall 1997segalcenterNo ratings yet

- French (Teɑtʁ (Ə) DƏ Lapsyʁd) Plays Absurdist Fiction PlaywrightsDocument3 pagesFrench (Teɑtʁ (Ə) DƏ Lapsyʁd) Plays Absurdist Fiction PlaywrightsAdoptedchildNo ratings yet

- All About #9 Five Russian Movies You Must Watch: Lesson NotesDocument6 pagesAll About #9 Five Russian Movies You Must Watch: Lesson NotesRebel BlueNo ratings yet

- SEEP Vol.16 No.2 Spring 1996Document84 pagesSEEP Vol.16 No.2 Spring 1996segalcenterNo ratings yet

- Gerould 1981Document4 pagesGerould 1981yurie arsyadNo ratings yet

- JADT Vol12 n3 Fall2000 Shafer Riggs Baeten Bryan BaumrinDocument84 pagesJADT Vol12 n3 Fall2000 Shafer Riggs Baeten Bryan BaumrinsegalcenterNo ratings yet

- SEEP Vol.22 No.3 Fall 2002Document105 pagesSEEP Vol.22 No.3 Fall 2002segalcenterNo ratings yet

- SEEP Vol.8 No.1 May1988Document44 pagesSEEP Vol.8 No.1 May1988segalcenter100% (1)

- The Cherry Orchard Study Guide FinalDocument17 pagesThe Cherry Orchard Study Guide FinalkokottoNo ratings yet

- SEEP Vol.22 No.1 Winter 2002Document92 pagesSEEP Vol.22 No.1 Winter 2002segalcenterNo ratings yet

- Early Russian Cinema (2003) PDFDocument15 pagesEarly Russian Cinema (2003) PDFAlexCosta1972100% (1)

- The Story Behind Shostakovich's Leningrad SymphonyDocument2 pagesThe Story Behind Shostakovich's Leningrad SymphonysuoivietNo ratings yet

- SEEP Vol.17 No.1 Spring 1997Document116 pagesSEEP Vol.17 No.1 Spring 1997segalcenterNo ratings yet

- Mikhail Baryshnikov Dances His Way To Tel Aviv - Haaretz Daily Newspaper - Israel NewsDocument13 pagesMikhail Baryshnikov Dances His Way To Tel Aviv - Haaretz Daily Newspaper - Israel NewsAscension ExpNo ratings yet

- Visosky Russian SingerDocument21 pagesVisosky Russian SingerSandra RuizNo ratings yet

- Costuming A 'Mermaid' at S.F. Ballet: 'Mermaid' Costumes Crucial PlayersDocument3 pagesCostuming A 'Mermaid' at S.F. Ballet: 'Mermaid' Costumes Crucial Playersapi-25907549No ratings yet

- Schnitzer Martin Eds Cinema in Revolution The Heroic Era of The Soviet Film 1973Document212 pagesSchnitzer Martin Eds Cinema in Revolution The Heroic Era of The Soviet Film 1973Diego AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Death of A SalesmanDocument2 pagesDeath of A SalesmanIuliana Stanoiu0% (1)

- European Researcher, 2013, Vol. (47), 4-3Document14 pagesEuropean Researcher, 2013, Vol. (47), 4-3Alexander FedorovNo ratings yet

- (Susan C.W. Abbotson) Masterpieces of 20th-Century (B-Ok - Xyz) PDFDocument238 pages(Susan C.W. Abbotson) Masterpieces of 20th-Century (B-Ok - Xyz) PDFFüleki Eszter0% (1)

- JCB Mini Excavator 8013 8015 8017 8018 Sevice ManualDocument22 pagesJCB Mini Excavator 8013 8015 8017 8018 Sevice Manualmrjustinmoore020389ocj100% (19)

- SEEP Vol.16 No.1 Winter 1996Document75 pagesSEEP Vol.16 No.1 Winter 1996segalcenterNo ratings yet

- SEEP-Vol.20 No.3 Fall 2000Document102 pagesSEEP-Vol.20 No.3 Fall 2000segalcenterNo ratings yet

- Time 1942 ShostakovichDocument4 pagesTime 1942 ShostakovichRodrigo BacelarNo ratings yet

- Chairunnisya Hamzah - Drama (Resume)Document4 pagesChairunnisya Hamzah - Drama (Resume)Fatria MointiNo ratings yet

- JADT Vol2 n3 Fall1990 Moody Krittzer Edwards Ruff Stephens KogerDocument90 pagesJADT Vol2 n3 Fall1990 Moody Krittzer Edwards Ruff Stephens KogersegalcenterNo ratings yet

- SEEP Vol. 11 No.1 Spring 1991Document80 pagesSEEP Vol. 11 No.1 Spring 1991segalcenterNo ratings yet

- SEEP Vol.14 No.1 Spring 1994Document93 pagesSEEP Vol.14 No.1 Spring 1994segalcenterNo ratings yet

- As Good Luck Would Have ItDocument29 pagesAs Good Luck Would Have ItELVISNo ratings yet

- The Russian CinematographyDocument1 pageThe Russian CinematographyAndrei GrumezaNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Modern PlaywrightsDocument4 pagesA Guide To Modern PlaywrightsSuman SanaNo ratings yet

- SEEP Vol.18 No.1 Spring 1998Document102 pagesSEEP Vol.18 No.1 Spring 1998segalcenterNo ratings yet

- 2 - M28 - DRAMA (S5P1) Pr. ChaouchDocument5 pages2 - M28 - DRAMA (S5P1) Pr. ChaouchKai KokoroNo ratings yet

- SEEP-Vo.21 No.1 Winter 2001Document88 pagesSEEP-Vo.21 No.1 Winter 2001segalcenterNo ratings yet

- SEEP Vol.3 No.2 June 1983Document26 pagesSEEP Vol.3 No.2 June 1983segalcenterNo ratings yet

- Iseki Tractor ts1910 2220 3110 3510 4510 Operator ManualDocument22 pagesIseki Tractor ts1910 2220 3110 3510 4510 Operator Manualchadmeyer270302xdi100% (28)

- Dovzhenko: The Last UtopianDocument7 pagesDovzhenko: The Last UtopianАліна ГуляйгродськаNo ratings yet

- SEEP Vol.23 No.3 Fall 2003Document98 pagesSEEP Vol.23 No.3 Fall 2003segalcenterNo ratings yet

- Gas Light - WikipediaDocument33 pagesGas Light - WikipediaDenemeNo ratings yet

- Glinka's Ambiguous And: The Birth ofDocument21 pagesGlinka's Ambiguous And: The Birth ofIvan JovanovicNo ratings yet

- SEEP Vol.10 No.3 Winter 1990Document64 pagesSEEP Vol.10 No.3 Winter 1990segalcenterNo ratings yet

- Within Fifteen Minutes, It Became Unbearable': Theatre FlopsDocument6 pagesWithin Fifteen Minutes, It Became Unbearable': Theatre FlopsRodrigo Garcia SanchezNo ratings yet

- 10 Black Theatre in AmericaDocument27 pages10 Black Theatre in AmericafffNo ratings yet

- 1 Takeaways From the Times Investigation Into ‘the Unpunished’Document7 pages1 Takeaways From the Times Investigation Into ‘the Unpunished’Gistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- 5 Sage, A Miniature Poodle, Wins Best in Show at WestminsterDocument27 pages5 Sage, A Miniature Poodle, Wins Best in Show at WestminsterGistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- A Lot of Chaos' - Bridge Collapse Creates Upheaval at Largest U.S. Port For Car TradeDocument3 pagesA Lot of Chaos' - Bridge Collapse Creates Upheaval at Largest U.S. Port For Car TradeGistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- To Justify His Immunity Defense, Trump Flips The Prosecution ScriptDocument6 pagesTo Justify His Immunity Defense, Trump Flips The Prosecution ScriptGistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- Trump Endures A Rugged Day in Court As Witness DetailsDocument8 pagesTrump Endures A Rugged Day in Court As Witness DetailsGistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- 4 The Runaway PrincessesDocument1 page4 The Runaway PrincessesGistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- Italy's New Abortion Law Is A Lesson in How Meloni GovernsDocument3 pagesItaly's New Abortion Law Is A Lesson in How Meloni GovernsGistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- U.N. Calls For Inquiry Into Mass Graves at 2 Gaza HospitalsDocument4 pagesU.N. Calls For Inquiry Into Mass Graves at 2 Gaza HospitalsGistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- King ShitDocument2 pagesKing ShitGistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- 4 Daily CartoonDocument1 page4 Daily CartoonGistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- Dear Pepper - Friend, Frenemy, or FoeDocument11 pagesDear Pepper - Friend, Frenemy, or FoeGistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- 2 David Means ReadsDocument2 pages2 David Means ReadsGistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- That's What Friends Are ForDocument2 pagesThat's What Friends Are ForGistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- Brainstorming The TopicsDocument3 pagesBrainstorming The TopicsGistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- Exerices BasicsentencepatternDocument4 pagesExerices BasicsentencepatternGistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- Will Be Going To: Will + Base Form of The Verb AM/IS/ARE Going To + Base Form of The VerbDocument2 pagesWill Be Going To: Will + Base Form of The Verb AM/IS/ARE Going To + Base Form of The VerbGistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- Exercise The Imperative Grammar Drills Reading Comprehension Exercises 109691Document2 pagesExercise The Imperative Grammar Drills Reading Comprehension Exercises 109691Gistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare100 - Ibook v4 FinalDocument231 pagesShakespeare100 - Ibook v4 FinalMartin ChodúrNo ratings yet

- Restaging Marathi TheatreDocument2 pagesRestaging Marathi Theatretvphile1314No ratings yet

- Zarzuela, Also Called Sarswela in The: Philippines OperaticDocument3 pagesZarzuela, Also Called Sarswela in The: Philippines OperaticDennise Amante AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Joseph Urick: Theatre ExperienceDocument1 pageJoseph Urick: Theatre ExperienceJoseph UrickNo ratings yet

- Drama Techniques in The Foreign Language ClassroomDocument140 pagesDrama Techniques in The Foreign Language Classroomdachus87100% (1)

- Kabuki: A Vibrant and Exciting Traditional TheaterDocument5 pagesKabuki: A Vibrant and Exciting Traditional TheaterArun KumarNo ratings yet

- Realism and Naturalism Theatre ConventionsDocument3 pagesRealism and Naturalism Theatre Conventionsapi-295713406No ratings yet

- Answer Key Sa Thor at LokiDocument2 pagesAnswer Key Sa Thor at Lokiジョン・ルイーズ カンティーナNo ratings yet

- The SwanDocument3 pagesThe SwanJoanna SmykNo ratings yet

- Creative Writing (Module 9)Document3 pagesCreative Writing (Module 9)Samson FegideroNo ratings yet

- Slides For Elizabethan TheatreDocument4 pagesSlides For Elizabethan TheatreSergioNo ratings yet

- Gas Girls Pitching PackageDocument12 pagesGas Girls Pitching PackageNew Harlem ProductionsNo ratings yet

- Drama Essay: Didactic ElementsDocument3 pagesDrama Essay: Didactic ElementsYakira DavidsonNo ratings yet

- A History of Theatre in SpainDocument20 pagesA History of Theatre in SpainMartín MartínNo ratings yet

- SubUrbia ProgramDocument2 pagesSubUrbia Programsdtco100% (1)

- Indian Traditional AND Folk TheatreDocument18 pagesIndian Traditional AND Folk TheatreSSP GamerNo ratings yet

- 01 Cultural Collaboration Theatre and SocietyDocument16 pages01 Cultural Collaboration Theatre and SocietychrimilNo ratings yet

- 1 4Q MusicDocument5 pages1 4Q MusicManilyn Naval EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 What Is Contemporary ArtDocument69 pagesLesson 1 What Is Contemporary ArtDaniel Nolasco100% (2)

- Rupakas, Types of Sanskrit DramaDocument3 pagesRupakas, Types of Sanskrit Dramarktiwary50% (2)

- Ballet (Disambiguation) : This Article Is About The Dance Form. For Other Uses, SeeDocument5 pagesBallet (Disambiguation) : This Article Is About The Dance Form. For Other Uses, SeeLynnaNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument9 pagesUntitledlala roqueNo ratings yet

- Sergei EisensteinDocument221 pagesSergei EisensteinPatitucci Lucila100% (1)

- Brook, Peter - The Empty SpaceDocument152 pagesBrook, Peter - The Empty SpaceChanakya Vyas95% (19)

- 07 - Chapter 2 PDFDocument53 pages07 - Chapter 2 PDFNilesh VyavhareNo ratings yet

- Intro To TheatreDocument3 pagesIntro To TheatresimanNo ratings yet

- The System Becomes The Method: Stanislavsky-Boleslavsky-StrasbergDocument53 pagesThe System Becomes The Method: Stanislavsky-Boleslavsky-StrasbergZenno MoriaNo ratings yet

- Modern DramaDocument23 pagesModern DramaZakaria DihajiNo ratings yet

- Jazz Dance Slide ShowDocument16 pagesJazz Dance Slide ShowCeris Anne Thomas100% (1)

- Internet Performances As Site-Specific ArtDocument12 pagesInternet Performances As Site-Specific Artalgaz_pez495No ratings yet