0% found this document useful (0 votes)

51 views18 pagesSoc Edmaps

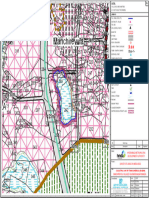

This document summarizes research on maps and map learning in social studies. It finds that while maps are important tools in geography and everyday life, students often struggle with map-related tasks. Assessments show students have difficulty interpreting, using, and making maps. The document also finds that while teachers say their goal is teaching higher-order map skills like analysis, their lessons tend to focus more on lower-order skills like map components and locations. Overall, the research suggests students need more effective instruction in maps and spatial thinking to develop important 21st century skills.

Uploaded by

allanmuchele95Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

51 views18 pagesSoc Edmaps

This document summarizes research on maps and map learning in social studies. It finds that while maps are important tools in geography and everyday life, students often struggle with map-related tasks. Assessments show students have difficulty interpreting, using, and making maps. The document also finds that while teachers say their goal is teaching higher-order map skills like analysis, their lessons tend to focus more on lower-order skills like map components and locations. Overall, the research suggests students need more effective instruction in maps and spatial thinking to develop important 21st century skills.

Uploaded by

allanmuchele95Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd