Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sobchack SciWhyDeclineFilm 2014

Uploaded by

nikomamuka8Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sobchack SciWhyDeclineFilm 2014

Uploaded by

nikomamuka8Copyright:

Available Formats

SF-TH Inc

Sci-Why?: On the Decline of a Film Genre in an Age of Technological Wizardry

Author(s): Vivian Sobchack

Source: Science Fiction Studies , Vol. 41, No. 2 (July 2014), pp. 284-300

Published by: SF-TH Inc

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5621/sciefictstud.41.2.0284

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5621/sciefictstud.41.2.0284?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

SF-TH Inc is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Science Fiction

Studies

This content downloaded from

89.135.109.100 on Mon, 30 Oct 2023 18:09:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

284 SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME 41 (2014)

Vivian Sobchack

Sci-Why?: On the Decline of a Film Genre in an Age of

Technological Wizardry

In some ways my title says it all, questioning as it does the present value of

the science-fiction film (and perhaps of science itself) at the start, and then

displacing technology from its traditional instrumental alliance with the genre

to what is an unexpectedly unsurprising conjunction with wizardry—and, by

implication, magic—at the end. And, indeed, since the millennium, there has

been an unprecedented rise in the mainstream production—and popularity —of

fantasy film and television, in which anything resembling empirical logic has

been trumped by magical thinking (of which more later).1 Certainly, sf has not

disappeared from our screens. Nonetheless, it has lost much of its pride of

generic place in amazing us with its spectacles or provoking us with resonant

narratives that both displace and deal with contemporaneous cultural concerns.

In relation to spectacle, this loss of privilege is the result of the exponential

increase in the use of CGI cinematic and televisual effects and their diffusion

across a variety of genres. “Special effects” have become naturalized and are

no longer quite so special, nor need their visible presence be bound (and

allegorized), as it has been in sf, to a “rationalization” that pretends to some

empirical basis in natural law or extrapolates from present science,

technology, and social organization. In many ways, then, the spectacles of

most sf film and television have become both expected and commonplace.

Moreover, as I will later discuss in some detail, not only have contemporary

digital effects (and the effects of digital technology more broadly) been

cinematically naturalized, but they also have been culturally internalized. In

sum, sf spectacles have lost much of their aura—the only recent exceptions

being Avatar (2009) and Gravity (2013), both of which were sufficiently

innovative to put the “special” back in their effects, “wow” audiences, and

achieve “blockbuster” status.2

In relation to narrative, sf always has also been—and still is—much more

constrained than fantasy because of its alliance with empirical logic and

instrumental process, and the need to explain its extrapolations and thus the

presence of its effects. Historically, this constraint (and restraint) has been an

asset rather than a liability. Today, however, whether set in outer space or

earth-bound, sf seems narratively grounded by a generic gravitas that disallows

its full participation in the wizardry and wish fulfillment allowed by the

narrative exemptions that grace fantasy—a genre that has come into its own

as such only since the millennium. Moreover, although often leaden, sf’s

narrative gravity seems also lightweight and trivial insofar as the genre has

primarily avoided any reflective relation (allegorical or not) to the significant

issues that trouble contemporary culture.3 Indeed, I can think of only three

recent mainstream sf films that explicitly addressed culturally relevant

concerns. Both In Time (2011) and Looper (2012) not only extrapolated from

This content downloaded from

89.135.109.100 on Mon, 30 Oct 2023 18:09:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SCI-WHY? 285

the commonplace awareness that “time is money” and that, with enough

money (an overt class issue), one could “buy time,” but they also resonated

with the intensified phenomenological sense that we “have no time” in digital

culture and that, in an imploding world (and planet), time itself is “running

out.” Refusing easy satire, Her (2013) extrapolated from our unprecedented

intimacy with personalized digital technologies and our increasing incapacity

for intimacy with other human beings in a comedy that was also both serious

and poignant.

These films, as well as a few others, are exceptions to sf’s narrative

decline. Overall, however, given the loss of the genre’s cultural ballast, we

have seen the recent slippage of narrative sf “proper” into lengthy but

meaningless chases (what were they doing in Prometheus [2012]?); endless

battles (in 2007, 2009, 2011, and 2014) with those alien mega-Legos known

as “Transformers”; and what seem like countless adaptations and “spin-offs”

of ersatz-sf “superhero” comic books such as the aptly-named Fantastic Four

(2005) “astronauts” who gain “superpowers” after being exposed to cosmic

radiation. Indeed, the latter makes explicit the increasing transformation of

screen sf into fantasy. Of the 63 fantasies from 2000 to 2013 that rank among

each year’s 25 top-grossing films in the domestic market, half were focused

on superheroes with either technologically altered and enhanced or

supernatural powers.4 Thus, in what follows, I want to speculate further about

the recent generic ascendancy of fantasy and its “enchantment” of American

popular movies and television series, as well as about the correspondent

decline of interest in sf. What might this historical shift mean in relation to a

pervasively reconfigured technological culture in which both genres serve as

co-constitutive discursive elements as well as poetic narratives dramatized in

specific chronotopic (or spatio-temporal) forms? 5

For several disparate reasons that I later hope to show are intimately

connected at a deep structural level to the digitization of American culture, as

suggested above, I date this historical shift to the turn of the new century.

This, however, is not only because X-Men and Unbreakable were theatrically

released in 2000 to great success, respectively ranking third and eighth at the

box office, whereas Space Cowboys ranked only twenty-fifth. I would also

argue that the millennium saw the beginning of the end of the predominantly

ironic stance toward the contradictions, vicissitudes, and “cultural logic” of

life in the period of “late capitalism,” characterized so famously in 1984 by

Fredric Jameson as “postmodernism.” Emphasizing new forms of

spatialization (both disorienting and euphoric) that collapsed and absorbed time

in the simultaneity and historical pastiche of an extensible present, postmodern

temporality was informed, as Jameson argued, by an “inverted

millenarianism” that replaced “premonitions of the future, catastrophic or

redemptive” with the sense of “the end of this or that” (53). In this context,

sf became a privileged genre. Its spatializations and often dystopic scenarios

were embraced not only by the public but also, and as never before, by the

academy, which saw sf as a chronotopic form not of “fantasy” but of late

capitalist “realism.”

This content downloaded from

89.135.109.100 on Mon, 30 Oct 2023 18:09:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

286 SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME 41 (2014)

It was thus fitting that the twentieth century ended with its own

“real”—and dystopic—sf scenario in “Y2K”: the millennial date change that

was projected to crash computer systems and wreak world-wide havoc.

Already tinged with postmodern irony, ultimately this catastrophic scenario

became emplotted as a full-out satire—because it never happened. Nonetheless,

in little over a year, postmodern irony and satire (despite Michael Moore)

seemed an inadequate and reprehensible response to the unanticipated and

catastrophic events of 11 September 2001 (9/11) and the non-stop plague of

catastrophes to follow (wars, climate change and its disastrous consequences,

global financial collapse, mass shootings, political gridlock) not only seemed

to concretely fulfill the last century’s “premonitions of the future” as “the end

of this and that” but also seemed to mark the end of the future itself. Although

still with us, irony and satire seem now merely a sign of impotence parading

as critical distance. Indeed, once so functional in dealing with the

contradictions of life in postmodernity, both irony and critical distance

seemed, after 9/11, not only overwhelmed but also outmoded.

In this regard, in Metahistory (1973), his important work on the

emplotment and deep tropological structure of four major narrative forms of

nineteenth-century historiography, Hayden White discusses satire and irony.

The form and its trope function not only to create critical distance but also to

disclose, as White writes, “the ultimate inadequacy of … visions of the world

emplotted dramatically” as a representation of reality (10; emphasis in

original). Unlike the genres of romance, comedy, and tragedy, satire and

irony reveal a “world grown old” (10). Moreover (and relevant to the

transition from millennial postmodernity to our present historical moment),

White argues that this revelation that the world has grown old functions not

only to “prepare … consciousness for a repudiation of all sophisticated

conceptualizations of the world” but, in so doing, also “anticipates a return to

a mythic apprehension of the world and its processes” (10). All this is to say

that beginning with the satire of a millennial catastrophe that never happened

shortly followed by so many that did, we have come to sense on a daily basis

that the world we live in has grown old. American culture has become

increasingly impatient with—and exhausted by—“sophisticated

conceptualizations of the world,” by social, economic, and political

complexities so intricate, so global, and so life-threatening that they not only

challenge notions of “critical distance” and “objectivity” but also defy

“comprehension.” Hence, although yapping dogs are still around, satire and

irony no longer seem able to hold the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse at

bay. Given this lived-world context since the millennium, my argument here

is that we have seen a gradual return—if with a digital difference—to “a

mythic apprehension of the world and its processes” apparent in both our

popular moving image media and more broadly in our culture.

Indeed, and counterintuitive as it may seem, this return to “mythic

apprehension” has emerged not only in the face of constant and global

catastrophe made visible by television (our “old” medium) but also from our

constant and powerful daily engagements with “new media.” Since the

This content downloaded from

89.135.109.100 on Mon, 30 Oct 2023 18:09:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SCI-WHY? 287

millennium, the consumer use of various digital technologies and applications,

primary among them the Internet and smartphones, has escalated, significantly

reconfiguring our experience of space, time, cognition, and process. We have

become increasingly engaged in modes of non-linear and “associative”

thought. Further expanding the spatializations of postmodernity, the Internet

and smartphone have also intensified the contraction of time. Spatially, all

things and all people seem technologically—and also

magically—“interconnected.” Temporally, our sense of sequence and duration

has given way to that of simultaneity. Cause and effect have imploded to brief

instants in which desire, affect, and agency coincide, and processes that “take

time” to produce desired outcomes try our ADHD attention as well as our

patience. In sum, even as new media seem immediately obsolete and never

immediate enough to satisfy us once we buy and use them, our desire for—and

enchantment by—their “immediacy” has also returned us (if with a significant

difference) to what White calls “mythical” reasoning, but what we today call

“magical thinking.” It has also led to the dramatic rise in the popularity of that

mode of “representation of the world” known as fantasy, which, unlike sf,

owes no allegiance to “realism.”

Although I will later characterize magical thinking in more detail, the

generic status of cinematic and televisual fantasy demands some initial

elaboration. As Brian Attebery writes, genres are not “clearly demarcated

territories … but fuzzy sets,” with a number of “prototypical examples” but

“no definitive perimeter” (“Elizabeth” 122; see also Attebery, Strategies 12-

13). As a set, however, fantasy seems a lot fuzzier than sf. Extremely

disparate in their themes and motifs, fantasy texts tended to be regarded

individually—only occasionally coalescing (as during WWII) in sufficient

quantity to be thought of, or written about, generically. Thus, in The Fantasy

Film (not insignificantly published in 2010), Katherine Fowkes laments the

scant attention paid to what she calls an “orphan” genre (171). The

“prototypical examples” of the fantasy films that structure her chapters (and

argument) are telling: The Wizard of Oz (1939), Harvey (1950), Big (1988),

Always (1989), Groundhog Day (1993), Spider-Man (2002), THE LORD OF THE

RINGS trilogy (2001-2003), The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and

the Wardrobe (2005), and the HARRY POTTER series (2001-2011).6 Noteworthy

are both the “fuzzy” diffusion of her selections and the number of films

released since the millennium. As Fowkes explains (quoting an industry

analyst writing in 2007), “Until recently the film industry has considered

fantasy ‘box office poison’” (1). By 2010, however, film scholar Harry

Benshoff writes in a blurb on the back of Fowkes’s book that fantasy has now

become “contemporary cinema’s most lucrative genre.”

If X-Men was the advent of fantasy’s rise to generic privilege, its actual

arrival began in 2001 with the release of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s

Stone and The Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring. Both begat two

extraordinary fantasy franchises and broke records at, respectively, first and

second in domestic box- office ranking for the year. Also released in 2001,

and updating a fairy-tale classic, was Jack and the Beanstalk: The Real Story.

This content downloaded from

89.135.109.100 on Mon, 30 Oct 2023 18:09:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

288 SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME 41 (2014)

Although it received little attention, it nonetheless planted a seed that, in

subsequent years, would yield a great deal more than a hill of beans. Indeed,

when I began this project in the first months of 2013, Jack and his beanstalk

were featured in an episode of Once Upon A Time (2011- ), a TV series based

on a “mash-up” of fairy tales that had emerged to great success in 2011.7

Only a few weeks after the episode aired, a cinematic Jack, the Giant Slayer

appeared—and was reviewed quite favorably by David Denby in The New

Yorker, who preferred it to yet another new fantasy release, Oz, the Great and

Powerful (“Kid’s Stuff” 56-57). And that’s not to mention (although I will) the

three films based on fairy tales released in 2012: Mirror, Mirror; Snow White

and the Huntsman; and the execrable (meaning “accursed” as well as “awful”)

Hansel and Gretel: Witch Hunters.

2001, however, was the year that inaugurated major changes in the

industry’s attitudes toward fantasy for (now obvious) economic and

technological reasons related to the year’s two blockbusters. Both Harry Potter

and Lord of the Rings were adaptations of beloved and widely known books,

and name recognition was a major factor in their production. Their huge box-

office success suggested that other well-known fantasy texts might generate not

only high revenues but also an ongoing franchise, this at a time when, as

Fowkes’s analyst put it, rather than a film’s actors, “the franchise [was] often

the star” (qtd. 31). Of course, also central to the two fantasies’ success were

their spectacular visual effects rendered by CGI, which had advanced

exponentially in the late 1990s. Perhaps less obvious but just as economically

compelling was the fact that fantasy films could easily secure a PG-13 rating

from the industry’s self-regulated MPAA and promised the broadest and

largest audience demographic in what was rapidly becoming an increasingly

segmented and niched mediascape. Finally, yet another incentive for the

industry to embrace fantasy was the extremely positive (and lucrative)

reception of both Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings abroad, suggesting that

fantasy would do well in export. And so began the unprecedented quantitative

rise in the genre’s mainstream production.

Fantasy’s rise and sf’s decline, however, is as much a qualitative as a

quantitative matter and, as I have suggested earlier, is not solely attributable

to technological and economic changes in the film industry. One need only

contrast the reception of Snow White and the Huntsman in 2012 with that same

year’s John Carter, an sf film based on novels by Edgar Rice Burroughs. Both

used extensive CGI, but John Carter was also screened in popular 3D and

IMAX formats. Unlike Snow White and the Huntsman, it also had a ready-

made series of sequels available for franchise. Nonetheless, John Carter was

a devastating commercial failure and set box-office records only in Russia,

whereas Snow White and the Huntsman was the highest-grossing film on its

opening weekend in the US, ranked seventeenth in the year’s box-office

rankings, and also was a big success in thirty other countries. One might

argue that the difference between the two films rested on star power—and that

Charlize Theron was a bigger audience draw than the unfortunately named

(and unknown) Taylor Kitsch. Thus it is also worth noting that, in the

This content downloaded from

89.135.109.100 on Mon, 30 Oct 2023 18:09:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SCI-WHY? 289

following year, two major mainstream sf films with popular stars—Elysium

with Matt Damon and the presciently-named Oblivion with Tom Cruise—were

also disappointments, ranking, respectively, only thirty-eighth and forty-first

at the domestic box office. It is never a truism in Hollywood that “if you build

it, they will come,” and we cannot hold the film industry solely, or even

primarily, responsible for the shift in the culture’s interest from sf to fantasy.

My data in arguing both a quantitative and qualitative shift in the two

genres’ production and reception is more than anecdotal. Selecting from a

much larger list of sf and fantasy films screened between 2000 and 2013, I

chose films that were clearly popular by virtue of being top grossers at the

domestic box office. I also included films that were sufficiently successful to

ensure that their titles would be familiar to most of us (whether we had seen

them or not). The criterion for selecting television series was that they had

aired for a minimum of two seasons. In my initial accountancy, however, I

disregarded such media specificity and grouped each year’s sf film and TV

series together and did the same for fantasy. What was surprising (and seemed

counter to my sense of sf’s “decline”) was that, as the years passed, each

genre’s increasing numbers stayed roughly equal. (Between 2000 and 2003,

for example, 22 sf films and TV series that fit my criteria were matched by

fantasy’s 26. Much more recently, and despite the increase in numbers

between 2011 and 2013, there were 47 sf and 55 fantasy films and television

series.)

Looked at separately, however, there were significant quantitative and

qualitative differences between both media and genres. Film fantasy saw the

continued success of the HARRY POTTER series, which unreeled between 2001

and 2011, and THE LORD OF THE RINGS trilogy, which ended in 2003 but

inaugurated THE HOBBIT trilogy in 2013. As mentioned previously, the number

of films based on fairy tales increased. Most notable was the increasing

number of superhero films over the years. Between 2000 and 2007, there were

only one or two per year, but from 2008 through 2013 each year saw three

or four. Some of the superhero films were derived from mythology but were

far outnumbered by those drawn from comic books. What is particularly

striking quantitatively is that between 2000 and 2004, the number of fantasy

and sf films was relatively equal but, beginning in 2005, fantasy began to

significantly overtake sf. In 2005, for example, there were six fantasies to two

sf films; in 2006, four fantasies to sf’s zero; in 2007, four fantasies to sf’s

two; and in 2008, six fantasies to sf’s zero. The numbers go on like this. In

contrast to fantasy’s steady ascent, sf’s peak years were more erratic: 2000

and 2001, for example, were sparse, with only Jurassic Park III and a remake

of Planet of the Apes attracting broad attention (respectively, they were ninth

and tenth at the box office). 2002, however, saw a significant number of

popular sf films included in the top 25 box office rankings: Signs (sixth), Men

in Black II (eighth), and Minority Report (seventeenth), as well as Star Trek:

Nemesis—which, released in mid-December, didn’t make the year’s rankings

but did very well. Then, in 2003, only three sf films were major successes:

the two Matrix sequels (fourth and ninth) and the third Terminator (eighth).

This content downloaded from

89.135.109.100 on Mon, 30 Oct 2023 18:09:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

290 SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME 41 (2014)

Another extremely good year for sf films did not occur until 2009, when

once again there were a significant number of releases, all of them among the

year’s 25 top grossers; Avatar (first), Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen

(second), the rebooting and rejuvenation of Star Trek (seventh), 2012

(fifteenth), and Terminator Salvation (twenty-third). In 2010, however,

Inception was the only unequivocal sf hit (sixth), its clever premise and novel

visual effects perhaps making up for its tedious dénouement in the

unconscious, which, as Peter Schjeldahl writes in another context, has the

“disheartening tendency … to be, in the usual way of other people’s dreams,

boring” (82). Although the number of sf releases increased somewhat in 2011

with Transformers: Dark of the Moon (second at the box office), only Rise of

the Planet of the Apes (eleventh) and Source Code (sixty-second) could

properly be called sf. Good numbers continued in 2012, but aside from The

Hunger Games (third at the box office), Men in Black III (fourteenth), and

Prometheus (twenty-fourth), most of the new releases did not do well: as

mentioned, John Carter was a major disaster given its cost (forty-first), the

lower-budget Looper got good reviews but drew a limited audience (forty-

fifth), and the remake of Total Recall did not meet studio expectations (fifty-

fifth). Indeed, if we compare the two film genres since the millennium, what

is most striking about all this box-office data is the big difference in the

number of each genre’s respective successes in securing the most domestic

ticket sales and largest audiences. From 2000 through 2013, the number of

fantasies in the 25 top-grossing films is not only double that of sf (63 to 30),

but fantasies also sell more tickets than sf: 44 fantasies are ranked among the

top ten high-grossers compared to sf’s mere seventeen. In sum, while certainly

not “disappeared,” it would seem that sf film has lost not only much of its

imaginative power but also much of its popularity.

Television tells another story even if it ends the same way. Between 2000

and 2013, although the numbers increased for both genres, there were more

sf series on television than there were fantasies. Qualitatively, however, a

disproportionate number of the sf series in the earlier years were spin-offs of

Stargate SG-1 (1997-2007). In 2003 and 2004, for example, one could watch

four different Stargate series each week—although, by 2009, two of them

were in their final season, as was the long-running Battlestar Galactica (2004-

2009). Moreover, between 2009 and 2011, a significant number of new prime-

time sf series failed. Although Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles

(2008-2009) made it (barely) through a second and final season, the highly

promoted and major network offerings FlashForward (2009-2010), The Event

(2010), and Terra Nova (2011) were canceled after only one season, and Joss

Whedon’s much-anticipated Dollhouse (2009) in less than that (also the fate

of his 2002 sf series, Firefly). Indeed, there were only two new sf series

appearing between 2009 and 2011 that lasted two or more seasons: 2009’s

remake of V (which ended in 2011) and 2011’s Falling Skies (still extant in

2014). Since 2011, only three new sf series have proven popular enough for

renewal: 2012’s Revolution, and 2013’s Almost Human and Under the Dome.

(However different, it seems significant that Falling Skies, Revolution, and

This content downloaded from

89.135.109.100 on Mon, 30 Oct 2023 18:09:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SCI-WHY? 291

Under The Dome all dramatize a highly ambivalent “neoprimitivism,” figuring

a world literally deprived of power—and digital technology. “Rules” of The

Dome, for example, specify that within the mysteriously enclosed town, phone

service, television, and Wi-Fi are not operative [Battaglio 5].)8

Fantasy, however, has fared better on television than has sf, despite its

initially lesser numbers than sf. Between 2009 and 2011, for example, only

a single fantasy series was cancelled after its first season, with a good many

others continuing their long run from earlier seasons, these including

Ghostwhisperer (2005-2010), Heroes (2006-2010), and Supernatural (2005-

). As well, 2011 saw the emergence of three new, and highly popular, series

that, in 2014, are in their fourth seasons: two are updates and mash-ups of

fairy and folk tales, Grimm and Once Upon a Time, and the third, Game of

Thrones, an epic and ersatz historical fantasy about warring dynastic families.

Moreover, fantasy’s numbers began to increase in 2012, catching up to and

overtaking sf. Indeed, from 2012 through the first quarter of 2014, a

significant number of new fantasy series have appeared: a revived Beauty and

the Beast, Sleepy Hollow, Marvel’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., DaVinci’s

Demons, Believe, and Resurrection. There are more yet to come, including

Heroes Reborn (scheduled to air in 2015). Particularly notable is that almost

all of these series have appeared on major broadcast television networks—and

during primetime hours. Comparatively, this has not often been the case with

sf, which tends to be “niched” on cable networks like Syfy. Thus, between

2012 and early 2014, although the number of new sf series is equivalent to

those of new fantasy series, only Revolution and Under the Dome are on major

networks; Continuum and Helix (now on hiatus until 2015) appeared on Syfy,

while The 100 and Star-Crossed (two 2014 offerings focused on teenage

protagonists) found a home on one of the lesser networks, CW.

So, again, why this generic and cultural shift that now gives preeminence

to fantasy—to mythical kingdoms and wizards, to fairy tales and wish

fulfillment, to superheroes with special powers? Although I’ve suggested a

number of coincident reasons for this shift, to respond seriously to this

question I think it necessary to consider what White called “mythic reasoning”

and we call “magical thinking.” And to do so, I want to return to

anthropologist Bronis³aw Malinowksi’s “Magic, Science and Religion” (1948),

an essay I drew on long, long ago (and in a culture that now seems far, far

away) for my Screening Space: The American Science Fiction Film (1987).

Malinowski argued that magic, science, and religion are endemic to all

cultures, but each differs in its expectations, practices, and social functions.

Although all three respond to the limited extent of human knowledge and

control (in particular, and respectively, of desire, the natural environment, and

death), Malinowski writes that each is a “special mode of behavior—a

pragmatic attitude built of reason, feeling, and will alike”; each is also “a

system of belief, and a sociological phenomenon as well as a personal

experience” (24). Moreover, all are always present in any culture (however

low- or high-tech), all are also in dialogic and dialectical relations with each

other, whether purposefully or not. (Such dialogic relations can be seen in the

This content downloaded from

89.135.109.100 on Mon, 30 Oct 2023 18:09:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

292 SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME 41 (2014)

2001 television season, which not only aired Stargate SG-1 and Star Trek:

Enterprise but also Charmed, Sabrina, the Teenage Witch, and Buffy, the

Vampire Slayer.) Thus, following Malinowski, I suggested in Screening Space

that the “special modes” of Malinowski’s triumvirate found their discursive

and poetic expression in the three related genres of science fiction, fantasy,

and horror. At the time, however, my focus was on the sf film and I paid no

real attention to fantasy—to which I, as well as the rest of the culture, had

given little, if any, serious thought.

What, then, characterizes magical thinking—and fantasy as its expressive

practice? As Malinowski writes, magical thinking’s “theory of knowledge” is

dictated “by the association of ideas under the influence of desire” (87). Over

and above “impersonal” or objective observation of the “laws of nature” upon

which science bases its practices and sf its extrapolations, magical thinking and

fantasy base their practices upon the belief “that no rigid boundary exists

between the mental and the physical, between the subjective and objective,”

and thus all elements of the world are “interrelated” (St. James, Handelman,

and Taylor, 235). Hence a major character in the 2014 romantic fantasy

Winter’s Tale tells her lover, “Magic is all around us. Everything is

connected.” As Malinowski elaborates, this view of the world’s systemic

“wholeness” emerges “from the idea of a certain mystic, impersonal power”

that can be mobilized practically so as to enable humans to overcome obstacles

and achieve desired outcomes (19).

In this regard, magical thinking and magical practice (in some cultures,

films, and television series, performed by a shaman or wizard versed in

appropriate spells and practical rituals) are “not directed so much to nature as

man’s relation to nature and to the human activities which affect it”

(Malinowski 75). Magical thinking and practice are thus motivated not by

objective curiosity but by subjective emotion and desire. Indeed, much like

fantasy narrative, magical thinking is preoccupied with the simultaneous gap

and bridge—the chiasmus—between the nature of will and the will of nature,

this reversibility creating correspondences between psychic and physical

worlds and between subjects and objects. Hence, with some few exceptions,

magical thinking has been regarded historically as a “pre-logical” form of

cognition—in early anthropology, of “primitive” peoples, and, in

developmental psychology, of very young children. Its primary forms of

logical connection operate by proximal association (or coincidence) rather than

sequential causality, and lead to what has been judged an illusory correlation

or causal fallacy. (A common example is students who use the same “lucky”

pen to take exams because they received an “A” the first time they used it.)

Such associational logic depends to a great degree on simultaneity, collapsing

the sequential temporality of “if, then” to the relative immediacy of “if, now.”

Thus, in vernacular terms, such logic is often described pejoratively as

“jumping to conclusions.”

Nonetheless, if science and rational logic have “laws,” so, too, does

magical thinking. Derived from what contemporary anthropologists call the

overarching “law of participation” in which everything is, dare I say,

This content downloaded from

89.135.109.100 on Mon, 30 Oct 2023 18:09:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SCI-WHY? 293

interconnected, are the laws of “contagion” and “similarity.”9 The law of

contagion affirms that “things that once have been in contact with each other

may influence or change each other for a period extending well past the

termination of contact” (Kerinan 48). Hence, magical spells and potions often

require some personal item or bodily residue that contains some “essence” of

the person with whom it was in contact. Moreover, the “direction of influence

between the source and the recipient can be reciprocal,” and “certain

properties of one can be transferred to the other.” The law of similarity

affirms a related form of correspondence in that “like affects like”; that is,

things “that resemble one another share fundamental properties” (Kerinan 48;

emphasis added). Hence, the use of mandrake roots or dolls or photographs,

all of which resemble human beings, in magical practice. Like the law of

contagion, the direction of the law of similarity’s influence can also function

reciprocally and “backward causation is possible (e.g., the belief that tearing

a person’s photograph will harm him or her)” (Kerinan 48).

In “civilized” Western culture, magical thinking in adults has generally

been seen as a sign of regression to naïve, childlike, or primitive behavior that

usually emerges in stressful situations in which the effectiveness of one’s

agency is in doubt. That is, “exhausted from the battle of coping, … magical

solutions promise shelter and temporary respite” from stress (St. James,

Handelman, and Taylor 643). Indeed, most accounts of adult magical thinking

see it as an attempt to reduce uncertainty and enhance one’s sense of control

instead of dealing rationally with the complexity of real-world problems. Thus,

it would be reasonable to claim that, since the millennium the growing

popularity of fantasy film and television is an indication of some mass

psychosocial regression in the face of great and ongoing cultural stress—a

mode of escape from the present to an imaginary, simpler, and mythic past

that has much more positive force than science-fictional projections of a

dystopic future, which, since 9/11 and the world-shaking events that have

followed, is no longer imagined as a time and place one would want to

inhabit.

Certainly, to a great degree, this claim makes sense. There is also another

view of magical thinking, however, that suggests it has more progressive

properties. Given magical thinking’s belief in the agential power of human

desire to directly affect the world as well as its correlative belief in the

mystical interconnectedness of all things, might not its expression in fantasy

take us recursively back to imagining a “better” future? Indeed, recent

research demonstrates that magical thinking is not only about reducing

uncertainty but also about world-building. “Through symbolic negotiation and

play, [magical thinking functions to] provide [subjects] the opportunity to

construct … a space of ambiguity in which they can find agency in contrast to

their current situation that offers very little” (St. James, Handelman, and

Taylor 645; emphasis in original). Moreover, “in the act of conjoining … dual

threads of fantasy and reality,” magical thinking enables what might be called

“chimerical agency”—“chimera” meaning not only “imaginary” or “fantastic”

but also, from Greek mythology, “an entity created as an amalgam of

This content downloaded from

89.135.109.100 on Mon, 30 Oct 2023 18:09:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

294 SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME 41 (2014)

previously separate entities” (St. James, Handelman, and Taylor 646;

emphasis added). Here, then, we might find contemporary fantasy’s parallel

to Donna Haraway’s postmodern, science-fictional, and playfully ironic

cyborg.

And, indeed, an ironic response to cultural contradiction is not a

characteristic of magical thinking. Rather, “in a space between reality and

fantasy that has been blurred and made ambiguous,” subjects are endowed

with a form of agency that allows for the construction of narrative scenarios

potentially able “to reconcile the expressive and cognitive dimensions of …

experience” (St. James, Handelman, and Taylor 648; emphasis added). That

is, magical thinking “empowers informants to transform coping with the day-

to-day paradoxes endemic to [contemporary life] into moral strivings” (St.

James, Handelman, and Taylor 647; emphasis added). This transformation

occurs through “narrative structures which re-enchant [the subjects’] lived

worlds” and affirm “a moral universe where good deeds are rewarded and evil

ones punished”—and, as in most fantasy scenarios, where loyalty,

steadfastness, and friendship counter treachery, self-interest, and greed (St.

James, Handelman, and Taylor 636). In this enchanted world, even magic is

resolved in terms of moral and poetic “justice”—hence the warning, “Be

careful what you wish for.” The fulfillment of “bad” or “evil” wishes in

fantasy tends to backfire on the ones who made them (again an instance of

“backward causation”).

Jack Zipes, a scholar of fairy tales, likewise believes that fantasy narratives

transform coping into moral strivings and the desire for a different and better

world than the one we live in (see, e.g., his The Irresistible Fairy Tale). As

Joan Acocella glosses his argument on the subject, “Because [fairy tales] are

grounded in a naïve morality,” [they] “offer us a ‘counterworld,’ which

encourages us to step back, consider the dubious morality of our own world,

and take steps to reform it” (77).10 Zipes’s argument is aptly illustrated in an

anonymous posting on the Internet Movie Database about Once Upon a Time

(the aforementioned series that remixes fairy tales and locates their characters

in the contemporary world as well as in fairy-tale settings). The poster seems

both reflective and sincere: “You have characters who you want to hate but

can’t, and characters you are just trying to figure out. You have people who

are in it for themselves. People who just want to help. It’s relatable (aside

from the fairy-tale aspect) to people who are working in their everyday life,

which makes this show so intriguing. If you are the kind of person that [sic]

wants to escape from your world, but you have to deal with this world, watch

this show!” Magical thinking and fantasy are in this sense not simply

regressive or escapist in function. Indeed, as Malinowski writes, “The function

of magic is to ritualize man’s optimism, to enhance his faith in the victory of

hope over fear. Magic expresses the greater value for man of confidence over

doubt, of steadfastness over vacillation, of optimism over pessimism” (90).

And, in our present life-world, looking toward the future, we have much to

be pessimistic about. Building a counter-world seems in order. Unfortunately,

however, world-building shouldn’t stop at the Sims or Second Life.

This content downloaded from

89.135.109.100 on Mon, 30 Oct 2023 18:09:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SCI-WHY? 295

I began this meditation on the ascendancy of fantasy by suggesting that

following the millennium, several disparate phenomena were involved in the

extraordinary rise of interest in a genre that previously was barely perceived

as such. More coincident and coeval than causal, the phenomena I discussed

were economic and technological changes in the film industry; distressing and

stressful natural and cultural events of great magnitude that followed one upon

another, confounding rational comprehension and solution as well as any

positive imagination of the future; disenchantment with (and often outright

repudiation of) sophisticated scientific conceptions of the world and the

naturalization of new technologies through daily use; and, last but not least,

a concurrent rise in magical, or associative, thinking. As I move toward

conclusion, however, I want to add one more phenomenon to these other “co-

incidents” that is hardly “coincidental” and provides the deep structure that

culturally links them all. As suggested earlier, this is not merely the

naturalization of digital technology but also, and more radical in its

implications, the culturally pervasive, yet personally intimate, internalization

of digital technology.

What might I mean by “internalization” in this context? Although written

in 1962, Arthur C. Clarke’s oft-quoted “third law” resonates throughout our

present life-world: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable

from magic” (21). The sufficiently advanced technology in question here is,

however, definitely not extraterrestrial. Thus, also quoting Clarke in a 2001

article entitled “Logic Versus Magic in Critical Systems,” software engineer

Peter Arney points out that “most of the devices we use daily, and rely on,

are now too complex for anyone but a specialist to understand…. When [a

certain level of] such … understanding becomes infeasible—for example the

cellular phone—perhaps we give up and accept the device as being ‘magic’”

(49). Indeed, I would argue that our constant quotidian use of “new” digital

technology (in particular, but not limited to, computers, the Internet,

smartphones, and other mobile devices) has led to a chronotopic

reconfiguration not only of our sense of space and time but also of our modes

of cognition. That is, despite their grounding in the rationalism of sequential

and algorithmic logic, all these digital devices have not only enabled the

depressing 24/7 visibility of our “world grown old” but also fostered our

cognitive “return to a mythic apprehension of the world and its processes”—to

magical thinking and the ascent of fantasy as the preeminent form of its

cultural expression.11

This internalization of digital technology has also led to contemporary

culture’s unprecedented fascination with superheroes. In this regard,

philosopher of technology Don Ihde has connected magical thinking to

“technofantasies” that refuse the unintended consequences and trade-offs that

occur with real-world technologies (47). Certainly, those hard- and software

engineers who created the Internet and our various devices never dreamed that

their rational designs and algorithmic applications would lead to the decline of

sequential logic or that their goals of connectivity and efficiency would lead

to an intense desire for “immediacy” and the effacement of technological

This content downloaded from

89.135.109.100 on Mon, 30 Oct 2023 18:09:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

296 SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME 41 (2014)

mediation. Thus, Ihde writes, “Desire-fantasy with respect to technologies

harbors an internal contradiction” (47). And pointing explicitly to the figural

function of superheroes, he continues: “On the one side, we want the super-

powers or enhancements which technologies can confer … but on the other,

the technofantasy is to have this enhancement be so totally transparent that it

becomes us. This is a Superman technofantasy; to have and to be the power

embodied” (47; emphasis in original). In sum, “technofantasy hype is the

current code for magic” (47). Magic in this fantasy is what we might articulate

as (im)mediacy: superheroes just “have” the power of technology—whether

born with it like Superman, or biologically altered in some way like the Hulk

or Spider Man, or technologically accessorized like Batman, or suited up like

Iron Man in a transparent mode of second nature. Superheroes in film and on

television efface the difference between science and magic, between sf and

fantasy. They are our culture’s “chimera,” embodied so as “to reconcile the

expressive and cognitive dimensions of … experience” and our couplings with

technology (St. James, Handelman, and Taylor 648; emphasis added).

Moreover, they hyperbolize our own—and a great deal less

powerful—“chimerical agency” as we wield our (always only nearly)

transparent digital devices. Better to save the world than to order a pizza

online.

It is worth remembering (for those old enough) how relatively recent our

digital devices are. Our desktop and personal computers became commercially

viable on a mass scale in the early 1980s. Public access to the Internet

followed shortly thereafter and allowed us to browse the web according to,

dare I say, our heart’s desire and its associational, rather than solely

rationalized, impulses. Although mobile (cellular) phones became

commercially available in 1983 (just a year before Jameson’s essay on the

logic of “late capitalism”), phones combining telephony, tele-vision, and

computing didn’t hit the stores until 1994 and weren’t referred to widely as

“smartphones” until 1997. 1994 was also the year that Amazon.com was

founded and that ordering pizza and other consumer goods became available

through the Internet—this only six years before the millennium.

On a daily basis, all these new devices and the speed of their processes

condensed time into a quasi-transparent yet mediated (im)mediacy that allowed

for the (almost) instant gratification or wish fulfillment of our desire for

communication, for information, for material things. Moreover, these devices

effaced spatial distance and expanded our sense of simultaneity, the sense that

everything and everyone was in contact and interconnected (“interrelated,” to

use Malinowski’s term). Given the speed at which our devices responded to

our desire, our patience and pleasure in duration shrank in proportion to our

desire for (im)mediacy, as did our interest in the sequential operations and

rationalized logic not only of process but also of explanation. Above all,

however, we increasingly spent much (if not most) of our daily lives in a real

ambiguous space which, like fantasy, conjoined the real and the virtual—this

conjunction constructing, quite literally, a chimerical agency not otherwise

This content downloaded from

89.135.109.100 on Mon, 30 Oct 2023 18:09:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SCI-WHY? 297

readily available when off our computers and smart phones—or outside of

fantasy narratives.

In sum, there is a deep structural homology between the cultural logic of

our daily digital practices and the associative logic of magical thinking. In this

regard, the digital revolution has wrought what Ihde would describe as an

“ironic technics”—irony, here, a function not of human critical consciousness

but, rather, of the “unintended or contingent consequences” of technological

design and practice (47). In this instance, our constant use of digital devices

not only promotes magical thinking’s laws (of participation, contagion, and

similarity) but also is homologous with magical practice. That is, recent

research suggests that magical practice “may operate as efficient causality,

evoking a technological utopia and acting as an imitation of technology or a

compensation for its effects” (St. James, Handelman, and Taylor 636;

emphasis in original). Moreover, “premised on the omnipotence of

technology” and now “embodied in consumer goods,” efficient causality finds

its expression “in a proclivity for magical solutions to life’s problems, that is,

quick and low-effort gains” (St. James, Handelman, and Taylor 636). Where

once in “primitive” societies, magical practice imitated technology, in the

magical logic of backward causation, technology now imitates magical

practice. Is it any wonder, then, that Hogwarts is a technical school? Or that,

in our Muggles world, in place of wands and spells and curses, the digital

technologies we live with on a daily basis have operationalized sequential

causality into something more efficient and low effort, the speed of its

processing transforming it into the efficient causality of magical thinking?

Science and science fiction demand due process. They are characterized by

both high-effort labor, temporal duration, and sequential operations, and

causation. Suffice it to say that if sf was the chronotopic form of late capitalist

realism before the millennium, fantasy has increasingly become the

chronotopic form of a “later capitalist realism” after it. How long this will be

the case is hard to predict—particularly in a culture that cannot imagine a

positive future and regards the recent escalation of catastrophe as a revelation

of an impending—and retributive—end time. Given that magic, science, and

religion are always at war with each other for cultural preeminence, when one

fails to satisfy, another will step into the breach. Indeed, on Easter weekend

of 2013 when I was writing the first version of this essay, NBC primetime

news featured a story on the film and television renaissance of the Bible.

Apparently, the History channel’s series on the good book captured more than

10 million viewers. Moreover, both Ang Lee and Ridley Scott were planning

Moses movies, and film director Darren Aronofsky was in post-production on

his retributive end-time film, Noah. Religion, Malinowski writes, “saves man

from a surrender to death and destruction” (51). (As we all know, Noah, his

family, and the animals survive to repopulate the earth.) It is telling, however,

that as I was updating this essay in late March of 2014 on the cusp of Noah’s

momentary release, Aronofsky described it as “a fantasy film taking place in

a quasi-Biblical world” (Friend 56). A few days later, the Variety reviewer

echoed this reference to fantasy, describing the film’s major battle sequence

This content downloaded from

89.135.109.100 on Mon, 30 Oct 2023 18:09:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

298 SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME 41 (2014)

as “an extended outtake from Middle-earth” (Foundas). The New Yorker

reviewer went even further, pointing to the film’s “Game of Thrones-style

helmets” and soldiers’ attempting to get on Noah’s ark as recalling “the

surging masses of the Lord of the Rings trilogy” (Denby, “Man Overboard”

74). A week later, however, Noah’s opening weekend supremacy at the box

office ($43 million) yielded to Captain America: The Winter Soldier. The

Marvel superhero took in $95 million (the highest domestic opening weekend

revenue ever recorded for an April release) while Noah dropped to second and

a paltry $17 million, and Divergent, an sf film based on a series of “young

adult” novels that made more than Noah on its opening weekend ($54

million), dropped to third with only $12 million in box office receipts. Magic,

science, and religion—all there (if not quite in that order), all in dialogue with

each other and the culture of which they are a part. Nonetheless, in the years

of magical thinking and digital wizardry, fantasy dominates the discussion.

Sci-why, indeed!

NOTES

1. Since I am interested in the relations between moving image media and large

segments of the American public, my focus in this essay is on popular sf and fantasy

film and television series that have been made for—and consumed by—mass audiences.

Hence my use of the terms “mainstream” and “popular.” I see popularity as a key

criterion for asserting such relations between media and culture, in the case of film

determined by box-office ranking and, in television series, by the series’ staying

power. Thus, in what follows, I do not address independent or art house films given

their limited distribution.

2. Both films were critical as well as popular successes, praised for their innovative

use of effects technology to create something that had not been seen before. Avatar

used motion-capture and 3D cinematography to achieve the depth of what seemed a

spatially-inhabitable alien world. Gravity combined new cinematographic techniques

with 3D and green-screen compositing to convey kinetically to audiences an imagined

sense of being in outer space.

3. Whereas most recent mainstream sf films seem narratively impoverished. As my

friend and colleague Kathleen McHugh notes in a paper delivered at the 2013 Eaton

Conference entitled “Science Fiction: For the Treatment of Depression,” the genre’s

various motifs linking planetary to personal catastrophe have been borrowed of late by

a number of extremely interesting independent and art house films focused on the

perceived loss of a future. Her presentation focused on three films released in 2011:

Lars von Trier’s Melancholia, Miranda July’s The Future, and Jeff Nichols’s Take

Shelter.

4. All of the domestic box office figures in this project are from Box Office Mojo,

accessed at <www.boxofficemojo.com>.

5. I refer here to Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of the “chronotope.” First outlined

during 1937-38 and subsequently developed in “Forms of Time and of the Chronotope

in the Novel,” the chronotope, as Michael Holmquist glosses it, is “a unit of analysis

for studying texts according to the ratio and nature of the temporal and spatial

categories represented. The distinctiveness of this concept … lies in the fact that neither

category is privileged; they are utterly interdependent. The chronotope is an optic for

reading texts as x-rays of the forces at work in the culture system from which they

spring” (435-36).

This content downloaded from

89.135.109.100 on Mon, 30 Oct 2023 18:09:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SCI-WHY? 299

6. In my project here, I follow the same exclusions and inclusions that guide

Fowkes’s generic discussion of fantasy. She excludes from her corpus sf and horror

films, both of which have their own established generic status, prototypes, and

variations. She does, however, include superhero films, which, although often linked

to sf, mark their heroes as, indeed, fantastic and share few of sf’s other interests or

themes. For the sake of clarity and also to avoid unnecessary double counting, I have

also excluded those very few films and television series that could be relegated to either

or both sf and fantasy, such as The Twilight Zone (1959-64), The X-Files (1993-2002),

and Lost (2004-2010). I have also excluded all animated films and television series.

7. The series was pitched to the networks early in 2002 but was turned down at the

time because of its fantastical nature.

8. Under the Dome’s executive producer Neal Baer relates the show’s success to

“the nation’s psyche,” explaining, “We’re all trapped under this biodome with

dwindling resources, … and we’re all worried about what the outcome is going to be”

(Battaglio 5).

9. There is an expansive classic and contemporary literature on magical thinking,

its logic and its laws. In concert with Malinowski’s much earlier essay, my

contemporary sources here are Rozin, Millman, and Nemeroff; Kerinan; St. James,

Handelman, and Taylor; and, in a more popular vein, Matthew Hutson.

10. This is a quite different view than that of Bruno Bettelheim, a Freudian who

saw fairy tales as precisely helping children to adjust to—and cope with—the emotional

turmoil caused by trying to make sense of ambiguity and contradiction in the world as

it is.

11. Obviously, however significantly weakened, our older forms of Enlightenment

logic are still with us. It is of note that, particularly on television, the ambiguous space

of fantasy occasionally attempts to reconcile Enlightenment logic and magical thinking.

For example, although both Grimm and Sleepy Hollow focus on supernatural characters

and events, they are also police procedurals.

WORKS CITED

Acocella, Joan. “Once Upon a Time: The Lure of the Fairy Tale.” The New Yorker

(23 Jul. 2012): 73-78.

Arney, Peter. “Logic versus Magic in Critical Systems.” Lecture Notes in Computer

Science 2043/Reliable Software Technologies—Ada Europe 2001. Ed. Dirk

Craenest and Alfred Strohmeir. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2001. 49-67.

Attebery, Brian. Strategies of Fantasy. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1992.

))))). “Elizabeth Enright and the Family Story as Genre.” Children’s Literature 37

(2009): 114-36.

Bakhtin, M.M. “Forms of Time and of the Chronotope in the Novel.” 1937-38. The

Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays by M. M. Bakhtin. Ed. Michael Holquist.

Trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin: U of Texas P, 1981. 84-258.

Battaglio, Stephen. “Why Dome Dominates.” TV Guide (15-28 Jul. 2013): 4-5.

Bettelheim, Bruno. The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy

Tales. 1975. New York: Vintage, 1977.

Clarke, Arthur C. Profiles of the Future: An Inquiry into the Limits of the Possible.

1962. Rev. ed. New York: Harper, 1973.

Denby, David. “The Current Cinema: Kid’s Stuff.” The New Yorker (18 Mar. 2013):

56-57.

))))). “The Current Cinema: Man Overboard.” The New Yorker (7 Apr. 2014): 74-

75.

Foundas, Scott. Review of Noah. Variety. 20 Mar. 2014. Online. 28 Mar. 2014.

This content downloaded from

89.135.109.100 on Mon, 30 Oct 2023 18:09:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

300 SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME 41 (2014)

Fowkes, Katherine. The Fantasy Film. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Friend, Tad. “Heavy Weather.” The New Yorker (17 Mar. 2014): 46-57.

Holmquist, Michael. “Glossary.” The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays by M.M.

Bakhtin. Ed. Michael Holquist. Trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist.

Austin: U of Texas P, 1981. 423-34.

Hutson, Matthew. 7 Laws of Magical Thinking: How Irrational Beliefs Keep Us

Happy, Healthy, and Sane. New York: Plume/Penguin, 2013.

Ihde, Don. “Of Which Humans Are We Post?” Ironic Technics. Copenhagen:

Automatic Press/VIP, 2008. 43-57.

Jameson, Frederic. “Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism.” New

Left Review 146 (July-Aug. 1984): 59-92.

Kerinan, Giora. “Effects of Stress and Tolerance of Ambiguity on Magical Thinking.”

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67.1 (1994): 48-55.

Malinowski, Bronis³aw. “Magic, Science and Religion.” 1925. Magic, Science and

Religion and Other Essays. 1948. Long Grove, IL: Waveland, 1992. 17-92.

McHugh, Kathleen. “Science Fiction: For the Treatment of Depression.” Unpublished

paper. 2013 Eaton Science Fiction Conference. Riverside, CA, Apr. 2013.

Rozin, Paul, Linda Millman, and Carol Nemeroff. “Operation of the Laws of

Sympathetic Magic in Disgust and Other Domains.” Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology 50.4 (1986): 703-12.

Schjeldahl, Peter. “The Art World: Dream Acts.” The New Yorker (11-18 Feb. 2013):

82-83.

Sobchack, Vivian. Screening Space: The American Science Fiction Film. 1987. New

Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 1997.

St. James, Yannik, Jay M. Handelman, and Shirley F. Taylor. “Magical Thinking and

Consumer Coping.” Journal of Consumer Research 38.4 (Dec. 2011): 632-49.

White, Hayden. Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century

Europe. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins UP, 1973.

Zipes, Jack. The Irresistible Fairy Tale: The Cultural and Social History of a Genre.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 2012.

ABSTRACT

This essay speculates about the generic ascendancy of fantasy in American popular

movies and television series since the millennium—and the correspondent

disenchantment and decline (although not disappearance) of science fiction. This shift

to fantasy in American culture seems the result of a number of discrete but coincident

cultural phenomena: major advances in CGI technology and changes in film industry

economic strategies; the inappropriateness of postmodern irony after 9/11 and the

ongoing (and highly visible) catastrophes to follow (wars, climate change and its

disastrous consequences, global financial collapse, mass shootings, political gridlock);

the perceived failure of science and “rational” thought to solve major problems; and,

most important, the impact of digital technology and consumer electronics on our daily

lives—and our modes of cognition. The essay argues that all of these phenomena have

encouraged (and in the case of digital technology, enabled) the rise of a form of

associational logic known as magical thinking—and fantasy film and television as its

primary mode of expression. The development of this argument draws upon

quantitative and qualitative data about the shifting popularity of sf and fantasy film and

television from 2000 through 2013, as well as anthropologist Bronis³aw Malinowski’s

1925 essay “Magic, Science and Religion” and more contemporary social science

research on magical thinking.

This content downloaded from

89.135.109.100 on Mon, 30 Oct 2023 18:09:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Sci-Why? On The Decline of A Film Genre in An Age of WizardryDocument18 pagesSci-Why? On The Decline of A Film Genre in An Age of WizardryRyan VuNo ratings yet

- Lo4 Science Fiction EssayDocument3 pagesLo4 Science Fiction Essayapi-295375953No ratings yet

- Tech-Noir Film: A Theory of the Development of Popular GenresFrom EverandTech-Noir Film: A Theory of the Development of Popular GenresNo ratings yet

- The Cinema in Flux: The Evolution of Motion Picture Technology from the Magic Lantern to the Digital EraFrom EverandThe Cinema in Flux: The Evolution of Motion Picture Technology from the Magic Lantern to the Digital EraNo ratings yet

- Shot on Location: Postwar American Cinema and the Exploration of Real PlaceFrom EverandShot on Location: Postwar American Cinema and the Exploration of Real PlaceNo ratings yet

- Introduction To (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004) by Angela NdalianisDocument41 pagesIntroduction To (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004) by Angela NdalianisSjelflakNo ratings yet

- Supercinema: Film-Philosophy for the Digital AgeFrom EverandSupercinema: Film-Philosophy for the Digital AgeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Dystopia on Demand: Technology, Digital Culture, and the Metamodern Quest in Complex Serial DystopiasFrom EverandDystopia on Demand: Technology, Digital Culture, and the Metamodern Quest in Complex Serial DystopiasNo ratings yet

- Out of Sync & Out of Work: History and the Obsolescence of Labor in Contemporary CultureFrom EverandOut of Sync & Out of Work: History and the Obsolescence of Labor in Contemporary CultureNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Gothic and Horror Film: Transnational PerspectivesFrom EverandContemporary Gothic and Horror Film: Transnational PerspectivesNo ratings yet

- Gonzalez Latino Sci-FiDocument13 pagesGonzalez Latino Sci-FiMarisaNo ratings yet

- Pandemic Protagonists: Viral (Re)Actions in Pandemic and Corona FictionsFrom EverandPandemic Protagonists: Viral (Re)Actions in Pandemic and Corona FictionsNo ratings yet

- Mark Fisher - What Is HauntologyDocument10 pagesMark Fisher - What Is Hauntologychuazinha100% (2)

- Screen Culture and the Social Question, 1880–1914From EverandScreen Culture and the Social Question, 1880–1914Ludwig Vogl-BienekNo ratings yet

- Bounded Rationality the Encryption: Humanity's Death Wish Comes Close to FulfilmentFrom EverandBounded Rationality the Encryption: Humanity's Death Wish Comes Close to FulfilmentNo ratings yet

- University of California PressDocument10 pagesUniversity of California PressChurrita de OroNo ratings yet

- NeoBaroque Aesthetics, Angela NdalianisDocument15 pagesNeoBaroque Aesthetics, Angela Ndalianisjuasjuas10No ratings yet

- PAGE - Polytemporality in Argentine Science Fiction FilmDocument20 pagesPAGE - Polytemporality in Argentine Science Fiction FilmDaniela DorfmanNo ratings yet

- The Potency of The Past in Comic Science Fiction: Aristophanes and Philip K. DickDocument22 pagesThe Potency of The Past in Comic Science Fiction: Aristophanes and Philip K. DickAndres A. GalvezNo ratings yet

- The Shining Author(s) : Fredric Jameson Source: Social Text, Autumn, 1981, No. 4 (Autumn, 1981), Pp. 114-125 Published By: Duke University PressDocument13 pagesThe Shining Author(s) : Fredric Jameson Source: Social Text, Autumn, 1981, No. 4 (Autumn, 1981), Pp. 114-125 Published By: Duke University PressJACKSON LOWNo ratings yet

- Neo-Mythologism Apollo and The Muses On The ScreenDocument42 pagesNeo-Mythologism Apollo and The Muses On The ScreenvolodeaTisNo ratings yet

- Film 1900: Technology, Perception, CultureFrom EverandFilm 1900: Technology, Perception, CultureAnnemone LigensaNo ratings yet

- Introduction Affecting A Knowledge of AntiquesDocument3 pagesIntroduction Affecting A Knowledge of AntiquesMichael Ramos-AraizagaNo ratings yet

- Clockwork Rhetoric: The Language and Style of SteampunkFrom EverandClockwork Rhetoric: The Language and Style of SteampunkRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (1)

- History in Images/History in Words: Reflections On The Possibility of Really Putting History Onto FilmDocument13 pagesHistory in Images/History in Words: Reflections On The Possibility of Really Putting History Onto FilmcjNo ratings yet

- Utopias Sci HubDocument18 pagesUtopias Sci HubDiego Mazacotte SNo ratings yet

- Decolonising James Cameron's PandoraDocument19 pagesDecolonising James Cameron's Pandorageevarghese52No ratings yet

- SF Trial Essay SampleDocument4 pagesSF Trial Essay SampleMelissa CowgillNo ratings yet

- Contemporary British and Italian Sound Docudrama: Traditions and InnovationsFrom EverandContemporary British and Italian Sound Docudrama: Traditions and InnovationsNo ratings yet

- Monsters in the Machine: Science Fiction Film and the Militarization of America after World War IIFrom EverandMonsters in the Machine: Science Fiction Film and the Militarization of America after World War IINo ratings yet

- Chapter 27 FERRANDO of Posthuman Born PDFDocument14 pagesChapter 27 FERRANDO of Posthuman Born PDFÇağıl Erdoğan ÖzkanNo ratings yet

- Scifi Narrative Conventions EssayDocument2 pagesScifi Narrative Conventions Essayapi-237200898100% (1)

- Gothic Things: Dark Enchantment and Anthropocene AnxietyFrom EverandGothic Things: Dark Enchantment and Anthropocene AnxietyNo ratings yet

- Elsaesser - Film Studies in Search of The ObjectDocument6 pagesElsaesser - Film Studies in Search of The ObjectEmil ZatopekNo ratings yet

- Mists of Regret: Culture and Sensibility in Classic French FilmFrom EverandMists of Regret: Culture and Sensibility in Classic French FilmRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Sci Fi Conventions Pre Exam Task-2Document14 pagesSci Fi Conventions Pre Exam Task-2api-250301089No ratings yet

- Nerves in Patterns on a Screen: An Introduction to Film StudiesFrom EverandNerves in Patterns on a Screen: An Introduction to Film StudiesNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Magic: Fantasy Media, Technology, and Nature in The 21st CenturyDocument17 pagesThe Politics of Magic: Fantasy Media, Technology, and Nature in The 21st Centuryandries alexandraNo ratings yet

- Image and Myth: A History of Pictorial Narration in Greek ArtFrom EverandImage and Myth: A History of Pictorial Narration in Greek ArtNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Representations of ArtificiDocument4 pagesContemporary Representations of ArtificiLuigi MasielloNo ratings yet

- Ideology as Dystopia: An Interpretation of Blade RunnerDocument15 pagesIdeology as Dystopia: An Interpretation of Blade RunnerIleana DiotimaNo ratings yet

- The Golden Age of Badness: ContinuumDocument12 pagesThe Golden Age of Badness: ContinuumOnur Can SümenNo ratings yet

- Mosaic Space and Mosaic Auteurs: On the Cinema of Alejandro González Iñárritu, Atom Egoyan, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Michael HanekeFrom EverandMosaic Space and Mosaic Auteurs: On the Cinema of Alejandro González Iñárritu, Atom Egoyan, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Michael HanekeNo ratings yet

- Alternative Worlds in Hollywood Cinema: Resonance Between RealmsFrom EverandAlternative Worlds in Hollywood Cinema: Resonance Between RealmsNo ratings yet

- Dystopia, Science Fiction, Posthumanism, and Liquid ModernityDocument54 pagesDystopia, Science Fiction, Posthumanism, and Liquid ModernityMaria Magdalena MądryNo ratings yet

- Virilio Evidence Explores Militarization of PeaceDocument35 pagesVirilio Evidence Explores Militarization of PeaceHellking45No ratings yet

- The Cinematic Sublime: Negative Pleasures, Structuring AbsencesFrom EverandThe Cinematic Sublime: Negative Pleasures, Structuring AbsencesNathan CarrollNo ratings yet

- Werner Herzog MasterClass Review Is It Worth It? - LearnopolyDocument35 pagesWerner Herzog MasterClass Review Is It Worth It? - LearnopolyQuentinNo ratings yet

- TYL PG Batch 2022-24Document61 pagesTYL PG Batch 2022-24Lipi's KhazanaNo ratings yet

- GANTZ (2004-2016) - Complete Anime Series, 3 Movies, Gantz O - 480p-720p DUAL Audio x264Document2 pagesGANTZ (2004-2016) - Complete Anime Series, 3 Movies, Gantz O - 480p-720p DUAL Audio x264julia_jayronwaldo50% (2)

- A B&C - List of Residents - VKRWA 15Document8 pagesA B&C - List of Residents - VKRWA 15blr.visheshNo ratings yet

- Tangled - WikipediaDocument121 pagesTangled - WikipediaJakariya MahmudNo ratings yet

- UG ChanakyaNationalLawUniversityCNLUPatna PDFDocument4 pagesUG ChanakyaNationalLawUniversityCNLUPatna PDFRaj KumarNo ratings yet

- MARY SHELLEY - Press KitDocument37 pagesMARY SHELLEY - Press KitThanya AraújoNo ratings yet

- Ftih Film School BroucherDocument40 pagesFtih Film School BroucherKarthik Yss GopaluniNo ratings yet

- Call Sheet PDFDocument2 pagesCall Sheet PDFGustavo PonneNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 Television Vocabulary 1Document2 pagesUnit 4 Television Vocabulary 1Monika SłupkowskaNo ratings yet

- Materials Engineering Course EnrollmentsDocument2 pagesMaterials Engineering Course EnrollmentsRakshit KeswaniNo ratings yet

- Oedipus CleanDocument41 pagesOedipus Cleanbrj4No ratings yet

- Grva Module 3 - Unit 2Document15 pagesGrva Module 3 - Unit 2KiwiTiwiTVNo ratings yet

- Data AtharvaDocument6 pagesData AtharvajitenderNo ratings yet

- Business Plan-GROUP 4Document8 pagesBusiness Plan-GROUP 4Christine Joy Mendigorin100% (2)

- Sue Parrill - Jane Austen On Film and Television, A Critical Study of The Adaptations-117-157Document41 pagesSue Parrill - Jane Austen On Film and Television, A Critical Study of The Adaptations-117-157Lorena RevertNo ratings yet

- Business Research ProposalDocument7 pagesBusiness Research ProposalPriyank AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Alist 05 DyOreDressOfcrIBM Engl 240124Document5 pagesAlist 05 DyOreDressOfcrIBM Engl 240124Rakesh SinghNo ratings yet

- Films (Vocabulary Exercises)Document2 pagesFilms (Vocabulary Exercises)Lucila CarrilloNo ratings yet

- 2021 Oscar NomsDocument16 pages2021 Oscar NomsJoanna ForestNo ratings yet

- Heroicfantasy SFMoviesDocument4 pagesHeroicfantasy SFMoviescall me as you might wantNo ratings yet

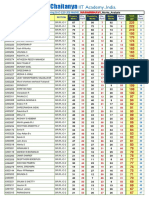

- 08-04-2023 Incoming Sr.C-120 JEE-MAINS - NAGARBHAVI - Marks - AnalysisDocument2 pages08-04-2023 Incoming Sr.C-120 JEE-MAINS - NAGARBHAVI - Marks - AnalysisSujatha SridharaNo ratings yet

- The Magical World of DisneyDocument2 pagesThe Magical World of DisneySamantha AlejandroNo ratings yet

- Ethan Frome Opinion - Selfish ProtagonistDocument2 pagesEthan Frome Opinion - Selfish ProtagonistLuis Gutierrez MelgarejoNo ratings yet

- Cinema and History: Archive Documentaries As A Site of MemoryDocument16 pagesCinema and History: Archive Documentaries As A Site of MemoryCarolina AmaralNo ratings yet

- Attendance Over SheetDocument4 pagesAttendance Over SheetIMC LIMITED VIZAG TERMINALNo ratings yet

- Tim BurtonDocument4 pagesTim Burtonapi-688982601No ratings yet

- Roll Number of Student Name of The Student Name and Zoom Link of Assigned TADocument2 pagesRoll Number of Student Name of The Student Name and Zoom Link of Assigned TAMANOJ KUMAR DASNo ratings yet

- KSEB Directory7Document1 pageKSEB Directory7rajikrajanNo ratings yet

- Othello by William ShakespeareDocument5 pagesOthello by William ShakespearerajeshNo ratings yet