Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mimesis and The Death of Differences in Graphic Art

Uploaded by

Ziyuan TaoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mimesis and The Death of Differences in Graphic Art

Uploaded by

Ziyuan TaoCopyright:

Available Formats

Mimesis and the Death of Difference in the Graphic Arts

Author(s): David Tomas

Source: SubStance , 1993, Vol. 22, No. 1, Issue 70 (1993), pp. 41-52

Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3684729

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to SubStance

This content downloaded from

192.246.224.206 on Thu, 22 Sep 2022 19:19:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mimesis and the Death of Difference

in the Graphic Arts

David Tomas

Why write, if not in the name of an impossible speech?

-Michel de Certeau

THE PENCIL IS A MARGINAL TECHNOLOGY in the pantheon of art tech-

nologies and in the history of modernism. To this day, it is associated with

the world of the artisan, and with antiquarian practices of the hand.' T

draw, as its semantic field suggests, includes such actions as to pull or haul,

to carry along and to change the shape of as well as to represent in line. Its

roots can be traced to the Old English word dragan (akin to) and to th

Greek word trekhein (to run).

The sensuality of a practice-a certain primitive "know-how" (de Cer-

teau, 72)--that unites eye, hand and pencil in a common activity is a

personal, private and tactile experience: the contact and pressure betwee

graphite and paper whereby friction and texture engender the quality and

status of a particular mark. In exceptional circumstances (one thinks of

Michelangelo's drawings of the crucifixion) these marks can becom

"grainy" with a certain "materiality of the body speaking its mother

tongue" (Barthes, 270).

Since the second quarter of the nineteenth century this practice has

existed in the shadows of a powerful new mode of pictorial reproduction

photography. Within fifty years of its first public appearance in 1839,

photography had democratized the production of mimetic images throug

the introduction of simple, easy-to-use cameras and efficient manufactur-

ing processes.2 However, this democratization was not achieved without

price, for a new relationship between the senses, a new way of making the

world emerged in its wake. In Walter Benjamin's incomparable phrase:

For the first time in the process of pictorial reproduction, photography

freed the hand of the most important artistic functions which henceforth

devolved only upon the eye looking into a lens. (219)3

While a drawing is commonly perceived to be a delicate creation, the

unique register of a "cultured" touch, the photograph is most often

SubStance #70, 1993 41

This content downloaded from

192.246.224.206 on Thu, 22 Sep 2022 19:19:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

42 David Tomas

described as a

puncture me (a

the pressure of

light) is theref

formed enco or

ference, a pho

impulses of th

1888 slogan: "Y

has done more t

hand, it has ref

eye. It has mec

and knowledge,

Land remarked

By making it po

subject matter s

barriers between

many of the sati

new group of ph

Hence the Polar

paign) in the in

consequence, ev

the human eye

organ. It is not

has been relegat

However, dur

expansion, ther

technologies (as

time, the first

multiplied by m

medium to rep

circulation is no

In his pioneerin

Talbot drew atte

reproducing wor

All kinds of eng

application of th

general nearly f

alter the scale, a

originals as we m

SubStance #70, 1993

This content downloaded from

192.246.224.206 on Thu, 22 Sep 2022 19:19:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mimesis 43

Moreover,

master dra

"multiplied

these obser

Walter Ben

Reproduct

groundwork

raphy and f

Benjamin's

concerning

original w

McLuhan's f

ogy is the c

affairs" and

intense just

However, an

not, to my

photographi

the size of a

The first is

In the pres

latest of wh

autonomy o

in a highly

practices o

demonstrate

in conjunct

pointing ou

represent a

genius, etc.

intervene in

gesture in t

detail its rel

rent debates

Thesecond

media often

shall see, wi

of complic

mechanism.

cultural gen

SubStance #70,

This content downloaded from

192.246.224.206 on Thu, 22 Sep 2022 19:19:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

44 David Tomas

terface and int

an interesting p

body and repre

Representation

Can one link d

the former mo

its preciousne

photography's r

register throu

perverse vision

representation

spatial and temp

the different g

threshold of m

pable physical

mutation gener

their own way

according to al

33) while reachi

One has only

threshold of vis

peculiar percep

bodiment under

of use in discrim

sentation. Are

as a photograph

other as conten

reside a spec in

signifier" (Lev

form to repre

qualities as text

through magn

high degree of

destabilized und

one level of pe

qualities are eith

SubSta

This content downloaded from

192.246.224.206 on Thu, 22 Sep 2022 19:19:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mimesis 45

at the expe

conditions

A New Kin

Although w

use in grou

ofpropelli

up-brough

and bodies

trap," for

tion, spatial

there is no

drawing's t

thus elimin

doubt rein

ize that we

perience a s

to transcen

cal authorit

direct dialo

attributes f

defining t

means to d

the world.

an interspac

an age-old

that has tr

But, as we

changed.

It is not surprising, therefore, that these "hybrid" drawings or

"hybrid" photographs (the confusion is structural) are characterized by a

strange lack of substance in connection with representation. Nor is it

surprising that we should find this deficiency to have been generated by a

primordial artifice-mimicry, with its paradoxical play of original and

copy-?since this condition appears to have been conjured up by a decep-

tive incantation: Are we looking at a drawing that has been disguised as a

photograph or a photograph disguised as a drawing? A simple trick or a

complex artifice? The answer is both. And it is precisely this ambiguity

SubStance #70, 1993

This content downloaded from

192.246.224.206 on Thu, 22 Sep 2022 19:19:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

46 David Tomas

between decep

perverse exchan

has pointed out

through the ar

understood for

to pay attenti

represents on

through the in

Blurring Figur

In an unusual

Caillois drew at

concluding, on

stitute a mecha

luxury" (25). T

status in relatio

coloration w

ure/ground con

for the mimick

confusion that

the psychopath

On the basis of observations, Caillois noted similarities between

mimicry and sympathetic magic ("according to which like produces like

and upon which all incantational practice is more or less based" (ibid.),

which led to the formulation of a rather unusual definition of mimicry: "an

incantation fixed at its culminating point and having caught the sorcerer in his

own trap" (27). However, Caillois drew back from the thrust of his defini-

tion with the remark that a "recourse to the magical tendency" in what he

described as "the search for the similar" could only "be an initial ap-

proximation" (ibid.). He suggested, instead, that this "search" might con-

stitute "a means, if not an intermediate stage" culminating in a final more

radical stage: a strange "disturbance in the perception of space" created by

an organism's almost perfect "assimilation to [its] surroundings" (27,28, 27).

This idea allowed Caillois to link mimicry, sympathetic magic and

psychopathology by way of a common perceptual condition. On the one

hand he traced this disturbance directly to the foundations of vision, given

that space can both be "perceived and represented" (28). On the other

hand, it was rooted in the instincts:

SubStance #70, 1993

This content downloaded from

192.246.224.206 on Thu, 22 Sep 2022 19:19:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mimesis 47

[A]longside t

creature tow

tion that ori

To this cond

sely, a "gen

the name ps

The feeling

tion from it

particular po

undermined

more specific

the disturba

Mimicry: T

Caillois's t

mimicry's

light on t

photographi

in the prese

the guise o

perception a

guish the fo

It is clear,

present case

adopted or a

first sight"

is presented

of the draw

in terms of

because it h

Finally, it

between pe

when we r

photograph.

(correspond

instantaneo

However,

completely

according t

SubStance #70,

This content downloaded from

192.246.224.206 on Thu, 22 Sep 2022 19:19:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

48 David Tomas

(lost its physic

photographic i

taneously been

on its identity

photograph rem

malaise and its

ception can be

mimicry. Specif

as a drawing, an

If we transpo

would be the p

photograph] to

symbolic value"

tent over and

Strauss, 64). Wh

contains (and th

mum "presence

since the drawin

in negative ter

sence-has been

physical presen

sonalization [of

space" (30). In

through an incr

own presence,

transformation

condition for e

nifier of its pre

Death by Mim

Having catalog

deception, are

photograph ga

singularity and

it has managed

in so doing has

sensorial regim

sentation; it now

SubSta

This content downloaded from

192.246.224.206 on Thu, 22 Sep 2022 19:19:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mimesis 49

guise of a dr

mimicking a

Caillois pro

sentation" m

way space is

place:

To these dispossessed souls, space seems to be a devouring force. Space

pursues them, encircles them, digests them in a gigantic phagocytosis. It

ends by replacing them. Then the body separates itself from thought, the

individual breaks the boundary of his skin and occupies the other side of

his senses. He tries to look at himself from any point whatever in space. He

feels himself becoming space, dark space where things cannot be put. He is

similar, not similar to something, but just similar. And he invents spaces of

which he is "the convulsive possession." (30)

There is, perhaps, no better description of the perceptual and spatial

consequences of the kind of photographic mimicry I have set forth in the

preceding pages. What we are witnessing in Caillois's portrayal of the

space of schizophrenia is the death of a consciousness, an individual, an

identity, a site of difference, by mimetic assimilation: a death that is signed,

as it were, in a perceptual contract. But this is no simple death. As Caillois

suggests, it is the necessary stage in the birth of another "purer" space-not

a hybrid or third space as currently understood9 because this new space

cannot exist outside of the system of logic which has made its existence

possible. One cannot speak of this other space in physical terms-of object

and place-since, according to mimetic logic, the two have fused. In fact,

Caillois tells us that this logic is the precondition for a new form of inertia

no longer cognizant of "either consciousness or feeling" (32). Thus, as

consciousness has vacated the body, so has presence vacated the drawing

and photograph. In its place we find a space without qualities, a space

without differentiating intelligence. With this space we have reached a

perceptual limit where difference mutates into pure similarity, presence

into pure absence.

The Sorcerer Caught in His Own Trap

However, we have already noted that the interspace is animated-

rendered minimally intelligible-by a subtle disturbance created by an

absence oscillating perversely between the visual attributes of opposing

modes of representation: Is this a drawing or is this a photograph? Insofar

as we engage in this play of mimicry and insofar as we are drawn into its

SubStance #70, 1993

This content downloaded from

192.246.224.206 on Thu, 22 Sep 2022 19:19:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

50 David Tomas

web of decepti

proximity of a v

final frontier o

extinction.

I would like to make two concluding observations in connection with

this frontier. First, it is in terms of this limit-in terms of the death of

difference-that one must begin to redefine the role of drawing today,

since this frontier has not only been reached at its expense (the expense of

a mimetic other), but the play of deception which has brought this frontier

into view has radically recontextualized drawing's position in the history

of representation. Second, if one were to extrapolate a politics of cultural

generativity from this play of mimicry, it would have to be rooted in the

death of representation itself-signalled most poignantly by the eclipse of

the "sorcerer" caught "in his own trap" (Caillois, 27). For this eclipse, this

death, are perhaps the only ways to account for the shimmering stillness

that saturates this kind of mimetic surface with the constant presence of an

absence. And in witnessing the sorcerer's death every time we engage this

surface, can it be that we are also witness to our own deaths beyond repre-

sentation?

As de Certeau writes in "The Unnamable":

There is nevertheless a first and last coincidence of dying, believing, and

speaking. In fact, all through my life, I can ultimately only believe in my

death, if "believing" designates a relation to the other that precedes me and

is constantly occurring. There is nothing so "other" as my death, the index

of all alterity. But there is also nothing that makes clearer the place from

which I can say my desire for the other; nothing that makes clearer my

gratitude for being received-without having any guarantee or goods to

offer-into the powerless language of my expectation of the other; nothing

therefore defines more exactly than my death what speaking is. (193-194)

University of Ottawa

WORKS CITED

Barthes, Roland. 'The Grain of the Voice," in The Responsibility of Forms: Critica

on Music, Art, and Representation. Trans. Richard Howard. New York: Hill and

1985.

Benjamin, Walter. "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproducti

Illuminations. Ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken

1976.

de Certeau, Michel. "The Arts of Theory" and "The Unnamable" in The Practice of

Everyday Life. Trans. Steven Rendall. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988.

SubStance #70, 1993

This content downloaded from

192.246.224.206 on Thu, 22 Sep 2022 19:19:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mimesis 51

Caillois, Rog

Land, Edwin

Levi-Strauss,

London: Rou

McLuhan, M

1964.

O'Doherty, Brian. "Inside the White Cube, Part II: The Eye and the Spectator," Art

Forum, Vol. 14, No. 8, 1976.

Talbot, William Henry Fox. The Pencil of Nature. New York: Da Capo Press, 1969;

facsimile of original 1844 edition.

NOTES

1. I am interested in this essay in a very particular form of drawing--dr

without the aid of perspective machines or optical drawing instruments

camera obscuras and camera lucidas. For histories of the latter two instruments s

H. Hammond, The Camera Obscura: A Chronicle (Bristol: Adam Hilger, 1981) a

Hammond and Jill Austin, The Camera Lucida in Art and Science (Bristol: Adam

1987).

2. For an early canonical statement of the power of photography to demo

the production of images see a "Brief Historical Sketch of the Invention of the A

Talbot. For an equally canonical statement in connection with the invention

step or Polaroid photography see Land, p. 7. On the industrialization of photo

see Reese V. Jenkins, Images and Enterprise: Technology and the American Photog

Industry, 1839-1925 (Baltimore & London: The Johns Hopkins University Press

3. For a contemporary statement to this effect, see Land, p. 7.

4. The origins of the word "photography" are discussed in H.J.P. Arnold, Wi

Henry Fox Talbot: Pioneer of Photography and Man of Science (London: Hutchinso

ham, 1977), p. 117.

5. The standard statement to this effect is Donna Haraway's "A Manifest

Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s," Socialist R

Vol. 15, No. 2, 1985, pp. 65-107. For a different approach see my "The Techn

Body: On Technicity in William Gibson's Cyborg Culture," New Formations

1989, pp. 113-129.

6. On hybridity, interdisciplinarity, and cultural generativity see James Cli

The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, an

(Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1988) and "Introduction: P

Truths," in James Clifford and George E. Marcus (eds.), Writing Culture: The Poet

Politics of Ethnography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), pp. 1-26

critique of Clifford's use of the terms hybridity and interdisciplinarity see my

Gesture to Activity: Dislocating the Anthropological Scriptorium," Cultural S

6-1, 1992, pp. 1-26.

A more sophisticated discussion of hybridity, third space, and cult

generativity is presented in Homi K. Bhabha "The Commitment to Theory,"

Pines and Paul Willemen (eds.), Questions of Third Cinema (London: BFI Publi

1989), pp. 111-132 (originally published in New Formations 5, 1988) and the int

SubStance #70, 1993

This content downloaded from

192.246.224.206 on Thu, 22 Sep 2022 19:19:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

52 David Tomas

with Bhabha entit

munity, Culture,

ever, Bhabha's notion of third space is of little use in dealing with

intermedia-generated spaces, since it does not acknowledge the possibility of a prac-

tice that cannot be "tamed and symbolized in language" (de Certeau, op. cit., p. 61).

7. For a recent discussion of tactile vision see Michael Taussig, "Physiognomic

Aspects of Visual Worlds," Visual Anthropology Review, Vol. 8, No. 1, 1992, pp. 15-28.

8. In later years, Caillois rejected his study as "fantastic," and returned to a more

conventional interpretation of insect mimicry: "the insect equivalent of human games

of simulation" (quoted in Taussig, op. cit., p. 28 n. 39). Of course, the scientific veracity

of Caillois's theory of mimicry has no bearing on its truth value in the present case,

since I am not dealing with mimicry in the insect world but with questions of media

interpenetration and hybridity in connection with a specific art practice. On the other

hand, I resist equating mimicry with simulation, especially in terms of its current

formulation as a kind of hermetically sealed second-order representational system

predicated on a play of copies, since mimicry posits, as its preexisting condition, a

direct perceptual relationship between an original and its copy-a relationship which

is, moreover, based on a clear direction of acculturation. The consequences of this

relationship and, in particular, the direction of its acculturation (notwithstanding

mimicry's obvious function of confusion vis-a-vis an original) are what interest me in

the case of photographically acculturated drawings.

9. Clifford, "Introduction: Partial Truths," op. cit., p. 26; Bhabha, "The Third

Space," op. cit., p. 211. Discussions of hybridity, in-betweenness, third spaces, and

cultural generativity do not attempt to specify the mechanisms that operate in these

situations as if the use of such words automatically guaranteed the appearance of a

new space, culture, or identity. As we can see from this case, these words refer to

complex processes which more often than not lie beyond their powers of repre-

sentation.

SubStance #70, 1993

This content downloaded from

192.246.224.206 on Thu, 22 Sep 2022 19:19:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Chromosome identification: Medicine and Natural Sciences: Medicine and Natural SciencesFrom EverandChromosome identification: Medicine and Natural Sciences: Medicine and Natural SciencesTorbjoern CasperssonNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 103.13.242.201 On Wed, 05 Jan 2022 05:40:32 UTCDocument6 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 103.13.242.201 On Wed, 05 Jan 2022 05:40:32 UTCShubhangi GoyalNo ratings yet

- SnowcrashDocument19 pagesSnowcrashapi-57809615233% (3)

- Bacon Design of CitiespdfDocument18 pagesBacon Design of CitiespdfYounes AlamiNo ratings yet

- The Explosion of Space - Architecture and T - Anthony VidlerDocument17 pagesThe Explosion of Space - Architecture and T - Anthony VidlersachirinNo ratings yet

- Video Nauman KraussDocument16 pagesVideo Nauman KraussElena ParpaNo ratings yet

- Ascott, Roy - Is There Love in The Telematic Embrace (1990)Document10 pagesAscott, Roy - Is There Love in The Telematic Embrace (1990)Kate WildmanNo ratings yet

- Perspecta 38 - After Forms - Lebbeus Woods - 2006Document9 pagesPerspecta 38 - After Forms - Lebbeus Woods - 2006Tarek ZeidanNo ratings yet

- Bolter, Jay David - The Desire For Transparency in An Era of HybridityDocument4 pagesBolter, Jay David - The Desire For Transparency in An Era of HybridityRaf BCNo ratings yet

- Tschumi and Walker - Bernard Tschumi in Conversations With Enrique WalkerDocument10 pagesTschumi and Walker - Bernard Tschumi in Conversations With Enrique Walkerlayla.j.arqNo ratings yet

- The Explosion of SpaceDocument17 pagesThe Explosion of SpaceZORRITO1993No ratings yet

- Simon Harrison - On The Management of KnowledgeDocument6 pagesSimon Harrison - On The Management of KnowledgeJuliet AquinoNo ratings yet

- Biometry and Antibodies Modernizing Animationanimating Modernity Edwin CarelsDocument10 pagesBiometry and Antibodies Modernizing Animationanimating Modernity Edwin CarelsMatthew PostNo ratings yet

- The Brain Is The Screen - Interview With Gilles Deleuze On 'The Time-Image'Document10 pagesThe Brain Is The Screen - Interview With Gilles Deleuze On 'The Time-Image'ideanovnaver.comNo ratings yet

- Picon Antoine Continuity Complexity & Emergence 2010Document12 pagesPicon Antoine Continuity Complexity & Emergence 2010Daniel DicksonNo ratings yet

- Marshall Mcluhan The Medium Is The Message Understanding Media CH 1 1 PDFDocument8 pagesMarshall Mcluhan The Medium Is The Message Understanding Media CH 1 1 PDFCüneyt YüceNo ratings yet

- Grids KraussDocument16 pagesGrids KraussDannyNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 213.149.62.203 On Mon, 23 Aug 2021 16:21:53 UTCDocument14 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 213.149.62.203 On Mon, 23 Aug 2021 16:21:53 UTCAurora LaneNo ratings yet

- Timespaces in Spectacular CinemaDocument18 pagesTimespaces in Spectacular CinemaseconbbNo ratings yet

- The Distracted Student Mind - Enhancing Its Focus and AttentionDocument8 pagesThe Distracted Student Mind - Enhancing Its Focus and AttentionSara H.No ratings yet

- Peter M. Boenisch - Intermediality in Theatre and PerformanceDocument9 pagesPeter M. Boenisch - Intermediality in Theatre and PerformanceNikoBitanNo ratings yet

- Deleuze, G. - Postcript On The Societies of ControlDocument6 pagesDeleuze, G. - Postcript On The Societies of Controlfakescribd100% (1)

- Design Museum TechnologyDocument6 pagesDesign Museum TechnologyMirela DuculescuNo ratings yet

- Taut - Fruhlicht (Daybreak)Document2 pagesTaut - Fruhlicht (Daybreak)DongshengNo ratings yet

- Art and Telecommunications 10 Years OnDocument7 pagesArt and Telecommunications 10 Years OnChris RenNo ratings yet

- WALLS - Review Quo VadisDocument12 pagesWALLS - Review Quo VadisHenri FelixNo ratings yet

- Booth Paul - Intermediality in Film and Internet - Donnie Darko and Issues of Narrative SubstantialityDocument19 pagesBooth Paul - Intermediality in Film and Internet - Donnie Darko and Issues of Narrative SubstantialityMiguel Sáenz CardozaNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of Seismic MigrationDocument18 pagesA Brief History of Seismic MigrationpospamNo ratings yet

- Theatre States: Probing The Politics of Arts-In-Prisons ProgrammesDocument4 pagesTheatre States: Probing The Politics of Arts-In-Prisons ProgrammesAnonymous TonNUtNKNo ratings yet

- Ratti, C. - Network SpecifismDocument3 pagesRatti, C. - Network Specifismarq torresNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Normative, Understanding TechnologyDocument13 pagesUnderstanding The Normative, Understanding TechnologySamuel ZwaanNo ratings yet

- Sloterdijk Cell Block Egospheres Selfcontainer 1 PDFDocument21 pagesSloterdijk Cell Block Egospheres Selfcontainer 1 PDFenantiomorphe100% (1)

- 005-Derrida - The ParergonDocument40 pages005-Derrida - The Parergonrenanpa26No ratings yet

- DeleuzeDocument6 pagesDeleuzeTekla ZukhbaiaNo ratings yet

- 3 KulturaDocument26 pages3 KulturaDomonkos HorváthNo ratings yet

- Perspectives On Aesthetic ComputingDocument10 pagesPerspectives On Aesthetic Computingfreiheit137174No ratings yet

- Biennial Manifesto Author(s) : Hans Ulrich Obrist Source: Log, No. 20, Curating Architecture (Fall 2010), Pp. 45-48 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 15/06/2014 03:57Document5 pagesBiennial Manifesto Author(s) : Hans Ulrich Obrist Source: Log, No. 20, Curating Architecture (Fall 2010), Pp. 45-48 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 15/06/2014 03:57ltroellNo ratings yet

- Telematic Dimension SpaceDocument8 pagesTelematic Dimension SpacePatrick MüllerNo ratings yet

- Ehn 1998 Manifest Bauhaus DigitalDocument12 pagesEhn 1998 Manifest Bauhaus DigitalIhjaskjhdNo ratings yet

- Chadabe - 1996 - The History of Electronic Music As A Reflection of Structural ParadigmsDocument5 pagesChadabe - 1996 - The History of Electronic Music As A Reflection of Structural ParadigmsAlessandro RatociNo ratings yet

- Cyberneticsandart PDFDocument10 pagesCyberneticsandart PDFmagdalena molinariNo ratings yet

- Projeting Age Tomas MaldonadoDocument9 pagesProjeting Age Tomas MaldonadoDouglas PastoriNo ratings yet

- Getting The Hands Dirty PDFDocument8 pagesGetting The Hands Dirty PDFBerk100% (1)

- Moving As ThingDocument17 pagesMoving As ThingMini GreñudaNo ratings yet

- Explorations in Art and TechnologyDocument8 pagesExplorations in Art and Technologyfreiheit137174No ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 27 Nov 2023Document14 pagesAdobe Scan 27 Nov 2023Ravindra Kr SinghNo ratings yet

- ROSEN - Change MummifiedDocument32 pagesROSEN - Change MummifiedGianna LaroccaNo ratings yet

- LeonardoDocument2 pagesLeonardoGaboNo ratings yet

- 27eb Content PDFDocument25 pages27eb Content PDFIlham Bagas SaputroNo ratings yet

- Trifonova NonhumanEyeDeleuze 2004Document20 pagesTrifonova NonhumanEyeDeleuze 2004ong22qNo ratings yet

- AsgfdadsfaDocument18 pagesAsgfdadsfaJorge del CanoNo ratings yet

- Posi TI VE SI DE: The Paths AheadDocument1 pagePosi TI VE SI DE: The Paths AheadSiddharth MNo ratings yet

- Sheet 1 PDFDocument1 pageSheet 1 PDFSiddharth MNo ratings yet

- Od C o E Gag G: FNTR U Ti N: N in FilmDocument10 pagesOd C o E Gag G: FNTR U Ti N: N in FilmLet VeNo ratings yet

- Borgatti Et Al 2009 - Network Analysis in The Social SciencesDocument5 pagesBorgatti Et Al 2009 - Network Analysis in The Social SciencesDESIGN PARTRIANo ratings yet

- Earth and Life Science CIDAMDocument15 pagesEarth and Life Science CIDAMAngelicq RamirezNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 43.251.89.56 On Mon, 08 Aug 2022 16:03:53 UTCDocument15 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 43.251.89.56 On Mon, 08 Aug 2022 16:03:53 UTCdhiman chakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Informit 522692128361478Document31 pagesInformit 522692128361478Erick GüitrónNo ratings yet

- Yale University, School of Architecture MIT PressDocument33 pagesYale University, School of Architecture MIT Press李涵溥No ratings yet

- The Aesthetics of Post-Realism and The Obscenification of Everyday Life The Novel in The Age of TechnologyDocument24 pagesThe Aesthetics of Post-Realism and The Obscenification of Everyday Life The Novel in The Age of TechnologyMonja JovićNo ratings yet

- Judging Contemporary Art With KantDocument18 pagesJudging Contemporary Art With KantZiyuan TaoNo ratings yet

- Marks, Laura U. - Video Haptics and EroticsDocument26 pagesMarks, Laura U. - Video Haptics and EroticsZiyuan TaoNo ratings yet

- How Beauty Disrupts SpaceDocument10 pagesHow Beauty Disrupts SpaceZiyuan TaoNo ratings yet

- Sanat Sosyolojisi EngDocument17 pagesSanat Sosyolojisi EngDoğan AkbulutNo ratings yet

- Lacoue-Labarthe - The Echo of The SubjectDocument71 pagesLacoue-Labarthe - The Echo of The SubjectZiyuan TaoNo ratings yet

- Copper Plate Photogravure Demystifying The Process PDFDocument235 pagesCopper Plate Photogravure Demystifying The Process PDFVishal ShujalpurkarNo ratings yet

- Sample DCCM, DLHTM and DCLRDocument38 pagesSample DCCM, DLHTM and DCLREagle100% (5)

- Description of Medical Specialties Residents With High Levels of Workplace Harassment Psychological Terror in A Reference HospitalDocument16 pagesDescription of Medical Specialties Residents With High Levels of Workplace Harassment Psychological Terror in A Reference HospitalVictor EnriquezNo ratings yet

- AIW Unit Plan - Ind. Tech ExampleDocument4 pagesAIW Unit Plan - Ind. Tech ExampleMary McDonnellNo ratings yet

- Developing Mental Health-Care Quality Indicators: Toward A Common FrameworkDocument6 pagesDeveloping Mental Health-Care Quality Indicators: Toward A Common FrameworkCarl FisherNo ratings yet

- 50 Life Secrets and Tips - High ExistenceDocument12 pages50 Life Secrets and Tips - High Existencesoapyfish100% (1)

- Noffke V DOD 2019-2183Document6 pagesNoffke V DOD 2019-2183FedSmith Inc.No ratings yet

- Case Study 2022 - HeyJobsDocument6 pagesCase Study 2022 - HeyJobsericka.rolim8715No ratings yet

- Flexural Design of Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Soranakom Mobasher 106-m52Document10 pagesFlexural Design of Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Soranakom Mobasher 106-m52Premalatha JeyaramNo ratings yet

- The Flowers of May by Francisco ArcellanaDocument5 pagesThe Flowers of May by Francisco ArcellanaMarkNicoleAnicas75% (4)

- Chryso CI 550Document2 pagesChryso CI 550Flavio Jose MuhaleNo ratings yet

- Niper SyllabusDocument9 pagesNiper SyllabusdirghayuNo ratings yet

- Hussain Kapadawala 1Document56 pagesHussain Kapadawala 1hussainkapda7276No ratings yet

- Exercise Reported SpeechDocument3 pagesExercise Reported Speechapi-241242931No ratings yet

- The Cave Tab With Lyrics by Mumford and Sons Guitar TabDocument2 pagesThe Cave Tab With Lyrics by Mumford and Sons Guitar TabMassimiliano MalerbaNo ratings yet

- Management of Breast CancerDocument53 pagesManagement of Breast CancerGaoudam NatarajanNo ratings yet

- Text Mapping: Reading For General InterestDocument17 pagesText Mapping: Reading For General InterestIndah Rizki RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Working With Regular Expressions: Prof. Mary Grace G. VenturaDocument26 pagesWorking With Regular Expressions: Prof. Mary Grace G. VenturaAngela BeatriceNo ratings yet

- LP.-Habitat-of-Animals Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesLP.-Habitat-of-Animals Lesson PlanL LawlietNo ratings yet

- AMBROSE PINTO-Caste - Discrimination - and - UNDocument3 pagesAMBROSE PINTO-Caste - Discrimination - and - UNKlv SwamyNo ratings yet

- 07.03.09 Chest PhysiotherapyDocument10 pages07.03.09 Chest PhysiotherapyMuhammad Fuad MahfudNo ratings yet

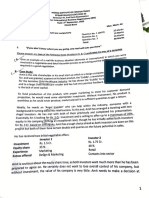

- Case Study Method: Dr. Rana Singh MBA (Gold Medalist), Ph. D. 98 11 828 987Document33 pagesCase Study Method: Dr. Rana Singh MBA (Gold Medalist), Ph. D. 98 11 828 987Belur BaxiNo ratings yet

- SakalDocument33 pagesSakalKaran AsnaniNo ratings yet

- Beginner Levels of EnglishDocument4 pagesBeginner Levels of EnglishEduardoDiazNo ratings yet

- Press ReleaseDocument1 pagePress Releaseapi-303080489No ratings yet

- Christiane Nord - Text Analysis in Translation (1991) PDFDocument280 pagesChristiane Nord - Text Analysis in Translation (1991) PDFDiana Polgar100% (2)

- Donna Haraway - A Cyborg Manifesto - An OutlineDocument2 pagesDonna Haraway - A Cyborg Manifesto - An OutlineKirill RostovtsevNo ratings yet

- Future Dusk Portfolio by SlidesgoDocument40 pagesFuture Dusk Portfolio by SlidesgoNATALIA ALSINA MARTINNo ratings yet

- Eaap Critical Approaches SamplesDocument2 pagesEaap Critical Approaches SamplesAcsana LucmanNo ratings yet

- The Saving Cross of The Suffering Christ: Benjamin R. WilsonDocument228 pagesThe Saving Cross of The Suffering Christ: Benjamin R. WilsonTri YaniNo ratings yet

- Khutbah About The QuranDocument3 pagesKhutbah About The QurantakwaniaNo ratings yet