Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kissinger World Order

Kissinger World Order

Uploaded by

Himanshu Mishra0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views12 pagesOriginal Title

Kissinger_World_Order

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views12 pagesKissinger World Order

Kissinger World Order

Uploaded by

Himanshu MishraCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 12

World Order

Henry k Kissinger

PENGUIN PRESS

Pb bythe Reguin Gioap

‘eagbin Group (USA) LL

575 Haden Scant,

[New Yo, New Yor 01

9

USA. Cana» UIC -fand = Austin

‘Now Zealand fais = Seth fics" China

A Penguin Rand Henee Company

Pst plik by Pega Pres

‘member of Pengin Grp (USA) LL. 2018

Copysghe © 201 by Henry A. Kisinge

Ponguin sippors copyright. Coprigh Fel reat

roo fies ech and restr a ivan ele. Thos

‘ton ofthis bk a or comping eth copys laws by net epodcog mrran

ot dsbsing any prof tin any br widen pines Sousa cre

‘and lowing Penguin tceminuc opi ns freer een

courage dvase ois,

you fr buyngan authored

ISBN STE S9RDH-6

Printed inthe Unie Sate of Ameria

vss7e be 42

INTRODUCTION

The Question of World Order

le 196t, as a young academic, I called on President Harry 8. Tru

man when I found myself in Kansas City delivering a speech. ‘To

the question of what in his presidency had made him most proud,

Truman replied, “That we totally defeated our enemies and then

brought them back to the community of nations. I would like to think

that only America would have done this.” Conscious of America’s vast

power, Truman took pride above all in its humane and democratic

values. He wanted to be remembered not so much for America’s victo-

ies as for its conciliations.

All of Truman’s successors have followed some version of this

narrative and have taken pride in similar attributes of the American

experience, And for most of this period, the community of nations

that they aimed to uphold reflected an American consensus—an in-

exorably expanding cooperative order of states observing common

rules and norms, embracing liberal economic systems, forswearing ter-

ritorial conquest, respecting national sovereignty, and adopting par-

ticipatory and democratic systems of governance. American presidents

of both parties have continued to urge other governments, often with

great vehemence and eloquence, to embrace the preservation and

2 | World Order

enhancement of human rights. In many instances, the defense of these

values by the United States and its allies has ushered in important

changes in the human condition.

‘Yet today this “rules-based” system faces challenges. The frequent

exhortations for countries to “do their fair share,” play by “twenty-

first-century rules,” or be “responsible stakeholders” in a common sys-

tem reflect the fact that there is no shared definition of the system or

understanding of what a “fair” contribution would be. Outside the

‘Western world, regions that have played a minimal role in these rules

original formulation question their validity in their present form and

have made clear that they would work to modify them. Thus while

“the international community” is invoked perhaps more insistently

now than in any other era, it presents no clear or agreed set of goals,

methods, or limits

Our age is insistently, at times almost desperately, in pursuit of a

concept of world order. Chaos threatensside by side with unprecedented

interdependence: in the spread of weapons of mass destruction, the

disintegration of states, the impact of environmental depredations, the

persistence of genocidal practices, and the spread of new technologies

threatening to drive conflict beyond human control or comprchension.

New methods of accessing and communicating information unite re-

gions as never before and project events globally—but in a manner

that inhibits reflection, demanding of leaders that they register instan-

taneous reactions in a form expressible in slogans. Are we facing a

period in which forces beyond the restraints of any order determine

the future?

Varieties of World Order

No truly global “world order” has ever existed. What passes for

order in our time was devised in Western Europe neatly four centuries

20, at @ peace conference in the

ct

4 | World Order:

the modern sensibility: it reserved judgment on the absolute in favor of

the practical and ecumenical; ie sought to distil order from ‘multiplic-

ity and restraint.

Russa, which was then reconsolidating its own order after the night

“Time of Troubles’ by enshrining principles distinctly at odds

with Westphalian balance: a single absolute rule, a unified religious

orthodoxy, and a program of territorial expansion in all directions.

Nor did the other major power centers regard the ‘Westphalian settle-

iment eo che extent they learned of tat all) as relevant to theit own

regions.

‘The idea of world order was applied to the geographic extent

Known to the statesmen of the time—a pattern repeated in ether re

Bions. This was largely because the then prevailing technology did not

SPeoUTaE OF even permit the operation ofa single global sytem, With

no means of interacting with each other on a sustained basis and no

framework for measuring the power of one region against another,

gach region viewed its own order as unique and defined the othere as

“barbarians'—governed in a manner incomprehensible to the estab

tn and irrelevant to its designs except asa threat. Fach de-

fined itself as a template for the legitimate organization of all

humanity, imagining that in governing. what lay before it, it was

ordering the world.

Place when the Roman Empire governed Europe as a uunity—basing,

itself not on the sovereign equality of starcs but fon the presumed

boundlessness of the Emperor's reach. In this concept, sovereignty in

‘he Buropean sense did not exis, because the Emperor held sway over

The Question of World Order | 5

“All Under Heaven.” He was the pinnacle of a political and cultural

hierarchy, distinct and universal, radiating from the center of the

world in the Chinese capital outward to all the rest of humankind.

The latter were classified as various degrees of barbarians depending

in part on their mastery of Chinese writing and cultural institutions

« cosmography that endured well into the modern era). China, in this

view, would order the world primarily by awing other socicties with

its cultural magnificence and economic bounty, drawing them into

‘elationships that could be managed to produce the aim of “harmony

under heaven.”

In much of the region between Europe and China, Islam’s different

universal concept of world order held sway, with its own vision of a

single divinely sanctioned governance uniting and pacifying the world.

In the seventh century, Islam had launched itself across three conti-

nents in an unprecedented wave of religious exaltation and imperial

expansion. After unifying the Arab world, taking over remnants of

the Roman Empire, and subsuming the Persian Empire, Islam came

to govern the Middle East, North Africa, large swaths of Asia, and

portions of Europe. [ts version of universal order considered Islam des-

tined to expand over the “realm of war,” as it called all regions popu-

lated by unbelievers, until the whole world was a unitary system

brought into harmony by the message of the Prophet Muhammad. As

Europe built its mukistate order, the Turkish-based Ottoman Empire

revived this claim to a single legitimate governance and spread its su-

premacy through the Arab heartland, the Mediterranean, the Bal-

ans, and Eastern Europe. It was aware of Europe's nascent interstate

order; it considered it not a model but a source of division to be ex:

ploited for westward Otoman expansion, As Sultan Mchmed the

Conqueror admonished the Italian city-states practicing an early ver-

sion of multipolarity in the fifteenth century, “You are 20 states... you

are in disagreement among yourselves . .. There must be only one

empire, one faith, and one sovereignty in the world.”

6 | World Order

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic the foundations of a distinet vision

of world order were being lad in the “New World” As Europe's

Scventeenth-century politcal and sectarian conflics raged, Puriten

settlers had set out to redeem God's plan with an “errand in the wil.

clerness” that would free them from adherence to established (and in

their view corrupted) structures of authority. There they would build,

88 Governor John Winthrop preached in 1630 aboard a ship bound for

the Massachusetts setlement, a “city upon a hill” inspiring the world

through the justness ofits principles and the power of i example,

4m the American view of world order, peace and balance would occur

naturally, and ancient cnmites would be set aside—onec other nations

Weis given the same principled say in their own governance that

Americans had in theirs. The task of foreign Policy was thus not so

‘much the pursuit ofa specifically American interest asthe cultivation

of shared principles. In time, the United States would become the in-

dispensable defender of the order Europe designed. Yet even as the

United States lent its weight co the effort, an ambivalence ‘endured—

for the American vision rested not on an embrace of the European

balance-oF power system but on the achievement of peace through the

spread of democratic principles,

Of all these concepts of order, Westphalian Principles are, at this

batting, the sole generally recognized basis of what exists of « world

order. The Westphalian system sprcad around the world as the frame-

work for a state-based international order spanning multiple civiliza-

fons and regions because, as the European nations expanded, they

‘carried the blueprine of their international order with them While

they often neglected to apply concepts of sovereignty to the colonies

and colonized peoples, when these peoples began to demand their in-

dependence, they did so in the name of Westphalian concepts. ‘The

Principles of national independence, sovereign statehood, national ine

‘rest and noninterference proved effective arguments against the

The Question of World Order | 7

SStonizerschemselves during the struggles for independence and pro-

‘on for their newly formed states afterward,

The contemporary, now global Westphalian systcm—what colo-

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Everything About Adani Vs Hindenburg ControversyDocument6 pagesEverything About Adani Vs Hindenburg ControversyHimanshu MishraNo ratings yet

- Act StatutesDocument41 pagesAct StatutesHimanshu MishraNo ratings yet

- Cover Letter KDocument1 pageCover Letter KHimanshu MishraNo ratings yet

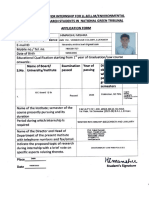

- Winter Internship Application FormDocument1 pageWinter Internship Application FormHimanshu MishraNo ratings yet

- CCI's Jurisdictional Issues and Remedies - A Comprehensive Analysis - Himanshu Mishra - NLIU BhopalDocument16 pagesCCI's Jurisdictional Issues and Remedies - A Comprehensive Analysis - Himanshu Mishra - NLIU BhopalHimanshu MishraNo ratings yet

- Case Study - Tragedy Averted - The Tale of MRDocument3 pagesCase Study - Tragedy Averted - The Tale of MRHimanshu MishraNo ratings yet

- Lecture 01 - Concept of Intellectual Property Law PatentsDocument14 pagesLecture 01 - Concept of Intellectual Property Law PatentsHimanshu MishraNo ratings yet

- Sample Write Up Marital Rape - Himanshu MishraDocument2 pagesSample Write Up Marital Rape - Himanshu MishraHimanshu MishraNo ratings yet

- Mhhs 4 GM NSXBDocument15 pagesMhhs 4 GM NSXBHimanshu MishraNo ratings yet

- Written Submissions Rejoinder Submissions of Senior Advocate Kapil SibalDocument32 pagesWritten Submissions Rejoinder Submissions of Senior Advocate Kapil SibalHimanshu MishraNo ratings yet

- Sanjay Gupta vs. Cottage Industries ExpositionDocument12 pagesSanjay Gupta vs. Cottage Industries ExpositionHimanshu MishraNo ratings yet

- 192 20240112 Pre 01 00 enDocument4 pages192 20240112 Pre 01 00 enHimanshu MishraNo ratings yet

- Aerodrome Conference 2024 Call For PapersDocument5 pagesAerodrome Conference 2024 Call For PapersHimanshu MishraNo ratings yet

- Pyu 24020413 715473Document2 pagesPyu 24020413 715473Himanshu MishraNo ratings yet

- Order Referring AMU Minority Case To A Larger BenchDocument10 pagesOrder Referring AMU Minority Case To A Larger BenchHimanshu MishraNo ratings yet

- DAILY CONTINOUS LOK ADALAT - South-East DLSADocument2 pagesDAILY CONTINOUS LOK ADALAT - South-East DLSAHimanshu MishraNo ratings yet

- Himanshu Economics Project 1Document24 pagesHimanshu Economics Project 1Himanshu MishraNo ratings yet

- UniversityofPennsylvania 311A BaxterWinnerDocument53 pagesUniversityofPennsylvania 311A BaxterWinnerHimanshu MishraNo ratings yet

- Stork Usearbitrationcopyright 1988Document26 pagesStork Usearbitrationcopyright 1988Himanshu MishraNo ratings yet

- Roberge Mediation 1983Document11 pagesRoberge Mediation 1983Himanshu MishraNo ratings yet

- Submission Guidelines and Editorial Policycibs 403597Document2 pagesSubmission Guidelines and Editorial Policycibs 403597Himanshu MishraNo ratings yet