Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Farlow - Treatment Options

Uploaded by

aruesjasOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Farlow - Treatment Options

Uploaded by

aruesjasCopyright:

Available Formats

Review Article

Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008;25:408–422 Accepted: October 10, 2007

Published online: April 3, 2008

DOI: 10.1159/000122962

Treatment Options in Alzheimer’s Disease:

Maximizing Benefit, Managing Expectations

Martin R. Farlow a Michael L. Miller b Vojislav Pejovic b

a Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Ind., and b Prescott Medical Communications Group,

Chicago, Ill., USA

Key Words Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease ⴢ Cholinesterase inhibitors ⴢ

Memantine ⴢ Pharmacotherapy ⴢ Combination therapy ⴢ Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause

Antioxidants ⴢ Ginkgo biloba of dementia in the elderly, affecting approximately 4.5

million people in the United States alone [1]. As the inci-

dence of AD in the United States and Europe is expected

Abstract to double by the year 2050 [2, 3], developing successful

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is becoming an increasingly heavy treatments to this complex disease is becoming an ever-

burden on the society of developed countries, and physi- increasing priority.

cians now face the challenge of providing efficient treatment Approved treatments for AD – the cholinesterase in-

regimens to an ever-higher number of individuals affected hibitors (ChEIs) and the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)

by the disease. Currently approved anti-AD therapies – the receptor antagonist memantine – offer some symptom-

cholinesterase inhibitors and the N-methyl-D -aspartate re- atic relief by targeting the cholinergic and glutamatergic

ceptor antagonist memantine – offer modest symptomatic neurotransmitter systems, respectively [4–9]. Other ther-

relief, which can be enhanced using combination therapy apies, such as statins, vitamin E, Ginkgo biloba extracts,

with both classes of drugs. Additionally, alternative therapies cognitive therapy, and psychological treatments have also

such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, vitamin E, been investigated clinically. Given the relatively limited

selegiline, Ginkgo biloba extracts, estrogens, and statins, as arsenal of currently approved anti-dementia drugs, it is

well as behavioral and lifestyle changes, have been explored vital for physicians to make the best use of available op-

as therapeutic options. Until a therapy is developed that can tions and, when appropriate, combine treatments in or-

prevent or reverse the disease, the optimal goal for effective der to maximize benefit for the patient.

AD management is to develop a treatment regimen that will

yield maximum benefits for individual patients across mul-

tiple domains, including cognition, daily functioning, and Dr. Martin Farlow receives grants from Eli Lilly & Co., Novartis, Ono/

behavior, and to provide realistic expectations for patients Pharmanet, Pfizer, Elan Pharm. He also is consultant for Abbott, Ac-

and caregivers throughout the course of the disease. This re- cera, Adamas, Cephalon Inc., Eisai Pharm, GlaxoSmithKline, Mediva-

view provides a basic overview of approved AD therapies, tion, Memory Pharm., Merck Res. Labs., Neurochem, Novartis, Oc-

discusses some pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic tapharma, Takeda, Toyama, Worldwide Clinical Trials and received

honoraria from Eisai, Forest, Novartis, Pfizer as a member of Speak-

treatment strategies that are currently being investigated, ers’ Bureau.

and offers suggestions for optimizing treatment to fit the Drs. Michael Miller and Vojislav Pejovic work for Prescott Medical

needs of individual patients. Copyright © 2008 S. Karger AG, Basel Communications Group, a contractor of Forest Laboratories, Inc.

© 2008 S. Karger AG, Basel Martin R. Farlow, MD

Department of Neurology, CL 291, Indiana University School of Medicine

Fax +41 61 306 12 34 541 Clinical Drive

E-Mail karger@karger.ch Accessible online at: Indianapolis, IN 46202-5111 (USA)

www.karger.com www.karger.com/dem Tel. +1 317 274 2893, Fax +1 317 274 5873, E-Mail mfarlow@iupui.edu

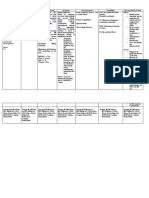

Table 1. Currently approved medications for the treatment of AD [10, 19, 27, 28, 32]

Second-generation ChEIs NMDAR

antagonist

donepezil rivastigmine galantamine memantine

oral transdermal

Dosing once daily twice daily once daily twice or once dailya twice daily

Starting 5 mg/day 3.0 mg/day 4.6 mg/day 8 mg/day 5 mg/day

Maximum 10 mg/day 12 mg/day 9.5 mg/day 24 mg/day 20 mg/day

Titration interval 4 weeks minimum 4 weeks recommended 4 weeks minimum 4 weeks minimum 1-week intervals

Recommended doses 5 and 10 mg/day 6–12 mg/day 9.5 mg/day 16–24 mg/day 20 mg/day

Peak plasma concentration, h 3–5 0.8–1.7 8–16 0.5–1.5 3–7

Effect of food on drug absorption none delays rate and none delays rate but not none

extent of absorption extent of absorption

Hepatic metabolism CYP 2D6 non-hepatic non-hepatic CYP 2D6 primarily

CYP 3A4 CYP 3A4 non-hepatic

Elimination half-life, h ⬃70 1.5 3.4 5–7 60–80

Drug–drug interactions yes none known none known yes none known

See prescribing information for complete details. a See text.

In this review, we discuss approved and investigation- Donepezil (Aricept쏐, Eisai; Pfizer, Inc.) has a long

al treatments for AD, methods for maximizing clinical half-life (approximately 70 h), which allows for once-dai-

benefits, and strategies to effectively manage patient and ly dosing and can be administered in the form of an oral-

caregiver expectations. ly disintegrating tablet [6, 7, 10]. Evidence suggests that

donepezil, in addition to providing cognitive and global

benefits, may be moderately effective at alleviating func-

ChEIs: The First Class of Agents Approved for the tional problems and behavioral changes such as depres-

Treatment of AD1 sion, anxiety, and apathy [6, 7]. As with other ChEIs, the

predominant side effects associated with donepezil are

The first 15 years of AD pharmacotherapy were pri- gastrointestinal (diarrhea, nausea; table 2) [10]. These

marily focused on the widespread degeneration of acetyl- symptoms are most severe during dose escalation, but

choline (ACh)-containing neurons in the brains of affect- may continue during maintenance therapy. Other re-

ed patients. ChEIs were developed with the idea of inhib- ported side effects include anorexia, headaches, muscle

iting acetylcholinesterase (AChE), thereby enhancing cramps, fatigue, syncope, sleep disturbances, and uri-

cholinergic neurotransmission. Tacrine (Cognex쏐, War- nary incontinence [7, 10, 11]. Donepezil is metabolized in

ner-Lambert), the first ChEI approved by the US Food the liver, but a portion of it (17%) is excreted unchanged

and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of in the urine [10, 12]. The 5-mg dose can be given safely to

mild-to-moderate AD, is no longer prescribed due to patients with mild-to-moderate hepatic and renal im-

problems with tolerability and hepatotoxicity. Three sec- pairment [13].

ond-generation ChEIs have been approved by the FDA Rivastigmine (Exelon쏐, Novartis Pharmaceuticals) [6,

for mild-to-moderate AD, with one (donepezil) recently 7, 14] selectively inhibits AChE in the central nervous sys-

receiving approval for the treatment of severe AD. All of tem, and also inhibits butyrylcholinesterase [7, 15]. It has

the ChEIs provide modest but significant improvements been speculated that this additional mechanism may be-

in cognition and global patient functioning and, in spite come important in advanced AD as AChE levels decline

of having different pharmacological profiles (table 1), are [16, 17], but recent measurements of butyrylcholinester-

considered to have similar efficacy [4–7]. ase activity in the synapses of patients with AD challenge

this view [18]. Rivastigmine has a very short half-life in

1

plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (1–2 h), thus requiring

A thorough review of the efficacy data for the ChEIs and memantine is

outside the scope of this article. For complete Phase III registration trials twice-daily dosing [19–21]. Statistically significant bene-

for these drugs, please refer to references 38–40, 54, 176–183. fits of rivastigmine have been observed for cognition,

AD Treatment Options Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008;25:408–422 409

Table 2. Adverse events1 associated with the use of ChEIs and memantine in patients with AD* [10, 19, 27, 28, 32]

Adverse events1 Donepezil Rivastigmine Galantamine Memantine

mild to severe AD oral transdermal

moderate AD

placebo drug placebo drug placebo drug placebo capsule2 patch2 placebo drug placebo drug

355 747 392 501 868 1,189 302 294 291 801 1,040 922 940

Abdominal pain – – – – 6 13 – – – 4 5 – –

Accident 6 7 12 13 9 10 – – – – – – –

Anorexia – – 4 8 3 17 2 9 3 3 9 – –

Anxiety – – – – 3 5 – – – – – – –

Asthenia – – – – 2 6 1 6 2 – – – –

Confusion – – – – 7 8 – – – – – 5 6

Constipation – – – – 4 5 – – – – – 3 5

Depression – – – – 4 6 – – – 5 7 – –

Diarrhea 5 10 4 10 11 19 3 5 6 7 9 – –

Dizziness 6 8 – – 11 21 2 7 2 6 9 5 7

Dyspepsia – – – – 4 9 – – – 2 5 – –

Ecchymosis – – 2 5 – – – – – – – – –

Fatigue 3 5 – – 5 9 – – – 3 5 – –

Headache 9 10 – – 12 17 2 6 3 5 8 3 6

Infection – – 9 11 – – – – – – – – –

Insomnia 6 9 4 5 7 9 – – – 4 5 – –

Malaise – – – – 2 5 – – – – – – –

Muscle cramps 2 6 – – – – – – – – – – –

Nausea 6 11 2 6 12 47 5 23 7 9 24 – –

Pain 8 9 – – – – – – – – – – –

Somnolence – – – – 3 5 – – – – – – –

Urinary tract infection – – – – 6 7 – – – 7 8 – –

Vomiting 3 5 4 8 6 31 3 17 6 4 13 – –

Weight decrease – – – – – – 1 5 3 2 7 – –

* Information taken from Prescribing Information for each drug. 1 Adverse events reported in at least 5% of patients receiving drug

and at a higher frequency than placebo-treated patients (the 10 most frequently occurring adverse events for each drug are indicated

in bold). 2 Capsule: 6 mg/day; patch: 9.5 mg/day.

global function, and activities of daily living (ADLs) [22], metabolism is almost completely (97%) nonhepatic (pri-

and the drug also may improve attention focusing [7]. marily occurring through cholinesterase-mediated hy-

Moreover, a recent study has demonstrated that treatment drolysis) [14], so possibilities of metabolic drug–drug in-

with rivastigmine may delay the onset of behavioral symp- teractions are minimal. In July 2007, the FDA approved a

toms and thus reduce the risk of initiating therapy with transdermal patch delivery system for rivastigmine, which

an antipsychotic [23]. The side effect profile for rivastig- demonstrated similar efficacy but better tolerability than

mine varies with dosing; in clinical trials designed to the oral preparation in a clinical trial [26, 27].

achieve the maximum tolerated dose, up to 50% of indi- Galantamine (RazadyneTM, previously Reminyl쏐, Or-

viduals in higher-dose groups experienced cholinomi- tho-McNeil) [6, 7, 28], in addition to inhibiting AChE,

metic side effects [24]. As with other ChEIs, gastrointesti- allosterically binds nicotinic ACh receptors, thereby

nal side effects associated with rivastigmine are common modulating the effects of ACh [29]. While binding nico-

(vomiting, nausea, diarrhea, anorexia, abdominal pain; tinic ACh receptors could influence neuronal processes,

table 2), but some can be circumvented using a slower the clinical benefit of this mechanism has not been estab-

dose-titration scheme, upwardly titrating monthly rather lished. Traditional dosing is twice daily, and an extended

than every 2 weeks [25]. Other notable side effects include release daily formulation is now available, allowing once

dizziness, headache, and fatigue (table 2). Rivastigmine daily dosing. Galantamine has been shown to provide

410 Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008;25:408–422 Farlow /Miller /Pejovic

some stabilization on measures of global functioning, events are rare. The most commonly reported adverse

cognition, behavior, and ADLs [30], although studies in- events that occur more frequently with memantine than

vestigating its effects on behavior and ADLs have pro- placebo include dizziness, headache, confusion, and con-

duced inconsistent results [30]. Approximately 30% of stipation (table 2) [32]. Memantine is primarily excreted

galantamine is excreted unchanged in urine, whereas the unchanged in urine (48%) [32], although in vitro evi-

rest is metabolized by hepatic enzymes [31]. Dose reduc- dence suggests the possibility of hepatic metabolism as

tion is recommended in patients with moderately im- well [43]. No metabolic interactions with other drugs

paired hepatic or renal function [28]. The most common- have been observed with memantine [32] (table 1). Medi-

ly reported adverse events include nausea, vomiting, cations that alkalize urine may reduce the renal elimina-

diarrhea, anorexia, and dizziness (table 2) [28]. Other re- tion of memantine, and dose reductions are recommend-

ported side effects include depression, headache, and ed for patients with severe renal impairment [32, 44].

weight decrease (table 2). In July 2005, the commercial

name of galantamine was changed from Reminyl to Raza-

dyne, in an effort to avoid confusion and dispensing er- Other Therapeutic Options in AD

rors with the diabetes treatment, Amaryl.

While the ChEIs and memantine have been designed to

affect specific aspects of chemical neurotransmission, oth-

NMDA Receptor Antagonists: The Second Class of er therapies seek to target biochemical stressors, such as

Agents Approved for the Treatment of AD inflammation, oxidation, and the disruption of hormonal

processes, all of which have been implicated in the neuro-

Memantine (Namenda쏐, Forest Laboratories, Inc.) nal loss observed in AD [8]. Some of the many therapies

[32], the first compound approved for patients in the investigated for their potential to prevent the onset, delay

moderate-to-severe stages of AD, is a moderate-affinity, progression, or reverse AD include anti-inflammatory

uncompetitive antagonist of the NMDA receptors drugs, antioxidants, selegiline, G. biloba, estrogen replace-

(NMDARs). Glutamatergic dysfunction can lead to an ex- ment, statins, and compounds designed to inhibit amyloid

cessive influx of calcium ions through NMDARs, leading and tau neuropathology. Currently, efficacy data for each

to neuronal death through mechanisms that are not clear- of these are either largely negative or inconclusive (most

ly understood [33]. Such ‘excitotoxicity’ has been impli- studies of compounds designed to inhibit amyloid or tau

cated in AD [34]. The pharmacological properties of me- neuropathology are preliminary or still in progress).

mantine are believed to prevent NMDAR-mediated exci- It has been hypothesized that inflammation, likely

totoxicity, while permitting normal synaptic activity [35]. caused (at least in part) by amyloid plaques, contributes

The half-life of memantine in plasma is approximately 70 to neuronal damage and eventual loss of synaptic func-

h, which theoretically allows for once-daily dosing; how- tion [45, 46]. Epidemiological studies have demonstrated

ever, the manufacturer, following established procedures, a lower incidence of AD in patients regularly using non-

recommends two daily doses of 10 mg each [32]. steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), suggesting

Memantine treatment of patients with moderate-to- that NSAID use may be protective against AD [47]. How-

severe AD has been shown to confer significant benefits ever, prospective trials evaluating NSAID use did not re-

on cognition, ADLs, global outcomes, and behavior (par- veal a symptomatic benefit in patients with AD [48, 49]

ticularly agitation and aggression) when administrated or mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [50, 51], and a trial

either alone or in patients already receiving donepezil [9, investigating a potential preventative role for naproxen

36–40]. Memantine has also been investigated in patients and celecoxib was halted due to concerns over cardiovas-

with mild-to-moderate AD, demonstrating significant cular risks [52].

results on cognition, behavior, and global status in one Another alternative approach involves protection

trial [41]; however, the FDA recently denied approval for against cellular damage caused by oxidative stressors. As

this indication as other trials suggest that memantine markers of oxidative injury are evident in postmortem

may not be efficacious at this stage of the disease [9, 42]. brain tissue of patients with AD [53, 54], it has been sug-

Memantine is safe and well tolerated, and trial discon- gested that oxidative processes are involved in the disease

tinuation rates due to adverse events in memantine-treat- pathogenesis. Antioxidants that have been investigated for

ed patients are comparable to those in placebo groups their potential to reduce the risk of AD include vitamins

[32]. In contrast to the ChEIs, gastrointestinal adverse A, C, and E, coenzyme Q, and selenium [8, 55, 56]. Clinical

AD Treatment Options Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008;25:408–422 411

trials with vitamin E have produced the most consistent Observational studies have revealed a lower incidence

results, suggesting that it may be the most promising anti- of AD in postmenopausal women taking estrogen, sug-

oxidant for delaying the onset or slowing the progression gesting that estrogen may have a protective role in AD

of AD [57, 58]. As a result of these findings, AD treatment [71]. However, recent studies indicate that the combina-

guidelines issued by the American Academy of Neurology tion of estrogen and progestin, or estrogen alone, may in

in 2001 advised considering vitamin E as an adjunctive fact increase the risk for dementia and adversely effect

treatment [24]. However, in a more recently published cognition [72, 73]. Estrogen supplementation has also

large, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients been linked to an increased risk of stroke, cancer, and

with MCI, no advantage for vitamin E over placebo re- other health problems [71, 74, 75]. Consequently, the

garding rate of cognitive decline or disease progression Women’s Health Initiative concluded in 2003 that the

was seen during the 3-year course of the study [59]. Since risks accompanying estrogen-progestin replacement

recent evidence also suggests that high doses of vitamin E therapy outweigh the potential benefits [72]. However, it

(6400 IU/day) may be associated with higher all-cause should be noted that data from a smaller subsequent trial

mortality rates [60], a more comprehensive clinical evalu- suggest that the timing of HRT in respect to the onset of

ation is required before the risk-benefits ratio of vitamin E menopause may be critical: early HRT initiation was as-

supplementation in AD can be determined. sociated with cognitive benefits compared to later initia-

A small number of clinical trials have also indicated tion, whereas later initiation was associated with cogni-

that selegiline, a monoamine oxidase B inhibitor with an- tive decline on the MMSE compared to participants who

tioxidant properties used for treating patients with Par- did not use HRT [76]. While debate continues over other

kinson’s disease [61], may be useful for the treatment of potential benefits of hormone replacement therapy, it is

AD. In a long-term clinical trial, selegiline-treated pa- not currently recommended specifically for the preven-

tients demonstrated significant improvement on the tion or treatment of AD.

Clock Draw Test and on the Mini-Mental Status Exami- Epidemiological evidence has also revealed a decreased

nation (MMSE) [62]. Clinical trial results have also indi- incidence of AD in patients taking the cholesterol-lower-

cated that treatment of AD with either selegiline, vitamin ing drugs known as statins [77], thereby prompting in-

E or both may slow the progression of the disease [58]; vestigation of their utility as an AD therapy [78]. A small

however, a recent Cochrane meta-analysis of 17 trials of prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of

selegiline for AD found very few significant treatment ef- simvastatin in AD demonstrated a reduced level of -

fects and recommended that no further studies need to amyloid in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with mild,

be conducted [63]. but not moderate AD [79]. A similar trial found that pa-

G. biloba extract, a popular herbal medication, is wide- tients with AD treated with atorvastatin performed sig-

ly used for its potential cognitive and neuroprotective ef- nificantly better than placebo-treated patients on a mea-

fects [64]. It has also been associated with antioxidant sure of cognition at 6 months (but not 12 months) [80].

properties and inhibition of platelet-activating factor [65]. Despite these results, it is not recommended that statins

While ginkgo has been promoted as a memory enhancer be used specifically for AD treatment. It has been sug-

for a number of years, its efficacy in patients with AD has gested that patients with AD may be overly susceptible to

not been validated by consistent data [66]. Several clinical adverse effects of statins due to pre-existing alterations in

studies have revealed a potential benefit of ginkgo for signal transduction and energy metabolism [81], although

treatment of patients with AD [66–68]; however, a recent this has not been clinically verified. Future studies are

randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in- expected to clarify the role of cholesterol and cholesterol-

volving 513 patients did not demonstrate significant ef- processing pathways on AD progression and to ascertain

ficacy over placebo [69]. An ongoing prevention trial whether the putative effects of statins in AD are related

aimed at evaluating the potential effect of ginkgo on de- to their lipid-lowering properties. Regardless of age or

laying progression to AD may reveal its utility in prodro- risk of dementia, all individuals are advised to maintain

mal stages of dementia (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: cholesterol within recommended levels.

NCT00010803; scheduled completion date: July 2009). Many studies are underway to investigate biochemical

G. biloba extract is generally well-tolerated: previous con- and immunological methods for blocking one or more of

cerns regarding risk of hemorrhage due to inhibition of the steps involved in amyloid and neurofibrillary pathol-

platelet-activating factor [70] have proven to be un- ogy. Such therapeutic approaches may ultimately lead to

founded [69]. additional ways of deterring, preventing, or altering the

412 Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008;25:408–422 Farlow /Miller /Pejovic

progression of AD; however, they will be required to un- sibility is realized, it is important that practicing physi-

dergo rigorous preclinical and clinical evaluation before cians optimize available symptomatic therapies in order

being approved by the FDA. Most of those approaches are to provide the best possible treatment regimen. Clinical

in relatively early stages of development, and it is unlikely issues that may influence the effectiveness of therapy in-

that they will be available for at least a few more years. clude early and efficient diagnosis, behavioral or lifestyle

modifications, patient compliance, and sequential or

Nonpharmacological Approaches combinatorial therapeutic approaches with available

In addition to pharmacological approaches to AD, a drugs.

number of nonpharmacological methods have also been

investigated. Although many of these studies have been Early and Efficient Diagnosis

poorly controlled and not subjected to the same rigorous Pathological changes and neuronal degeneration in

criteria as trials of pharmaceutical agents [82], recent ev- AD begin many years before a clinical diagnosis can be

idence suggests that there may be a role for various types made [88–91]. Since such changes are likely cumulative,

of cognitive training and psychological intervention in diagnosis and intervention at an early, preclinical stage of

the treatment of AD. A meta-analysis [83] showed that the disease can be of paramount importance in preserv-

various cognitive therapy methods may improve or slow ing cognitive function [92].

the rate of decline of cognitive and functional abilities in The first signs of cognitive complaints can indicate a

patients with AD, and that restorative strategies, which syndrome called mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [93,

are designed to restore functioning through repeated 94], which is defined as a ‘cognitive decline greater than

cognitive challenges, are typically more effective than that expected for an individual’s age and education level

compensatory strategies designed to ‘work around’ cog- but that does not interfere notably with activities of daily

nitive deficits [83]. A Cochrane meta-analysis of trials us- life’ [95]. The significance of MCI is well illustrated by an

ing reality orientation, in which patients are regularly observation that 80-year-old patients with MCI can be

presented with cues relating to their environment, also expected to progress to AD at a rate of 12% per year, com-

suggested potentially significant benefits for patients pared to 2% per year for control, age-matched subjects

[84]. More recently, in a trial involving untreated patients [96]. A 2003 conference dedicated to MCI resulted in a

with AD, participants undergoing regular, intensive real- diagnostic algorithm that can be used to identify four

ity orientation and cognitive stimulation demonstrated MCI subtypes [93, 94], one of which, the single-domain

better cognitive performance than the patients in the amnestic MCI (also referred to as ‘amnesic MCI’ or

control group [85]. Such gains may be maintained for sev- ‘aMCI’), is particularly associated with a high probability

eral months after the cessation of the treatment, although of conversion to AD: one study found a conversion rate

data on the persistence of such benefits are sparse [83]. to AD of approximately 49% (over 2.5 years) for patients

Furthermore, psychosocial interventions such as caregiv- with amnestic MCI, compared to approximately 27% for

er support, counseling, education, and environmental patients with nonamnestic forms [97]. The identification

modifications that minimize stressful situations for pa- of factors that best predict the conversion from MCI to

tients with AD have also been shown to minimize both AD is an area of intense research [97–101].

patient behavioral problems [86] and caregiver distress Current expert opinion recommends careful monitor-

(see below) [87]. As a caveat, it should be noted that it is ing of patients who show symptoms of amnestic MCI,

often difficult to ascertain whether the benefits of cogni- since they may have reached a prodromal stage of AD [95,

tive therapy in AD are due to the methods themselves or 102, 103]. Although standard diagnostic tools for demen-

the general stimulation of patients through regular inter- tia, such as the MMSE, may not be sensitive enough to

personal interactions with caregivers, family members, detect memory problems indicative of MCI [95], efforts

and health care professionals [83]. are being made to develop more effective diagnostic tools

[104]. In addition, corroboration and characterization of

patient memory complaints from family members or oth-

Maximizing Benefit er caregivers can help identify individuals at the highest

risk of progressing from MCI to AD [105–108]. Finally,

Ultimately, the hope for a truly revolutionary AD ther- emerging brain imaging techniques hold the promise of

apy lies in the potential of some pipeline compound to an early, accurate, and sensitive detection of the underly-

prevent or delay the onset of the disease. Until this pos- ing AD pathology [109–112], although at this point the

AD Treatment Options Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008;25:408–422 413

cost-effectiveness of these tools is still a matter of conten- [127], coffee [128, 129], curry [130, 131], and fish [132–

tion [113–115]. 134] is associated with a lower risk of AD.

For individuals whose changes in cognitive, function- Activities involving complex cognitive functioning,

al, or behavioral performance indicate progression to- such as reading, participating in board games, or playing

ward AD, there are numerous standard and validated musical instruments, may also help protect against the

evaluation tools for measuring the degree of impairment development of dementia [135]. In addition, regular phys-

and monitoring progression of the disease. The MMSE ical activity has been associated with the maintenance of

and the Clock Drawing Test are most commonly used in healthy brain function, increased neuronal survival, pro-

a clinical setting; however, a recent study comparing 13 tection against neuronal injury, and a reduced risk of de-

screening instruments with an administration time of 10 mentia in cognitively normal elderly persons [136–139].

min or less suggests that the Mini-Cog, the Memory Im- Physical activity has been also associated with improved

pairment Screen, and the General Practitioner Assess- cognitive function in older adults with cognitive impair-

ment of Cognition show potential for widespread clinical ment and dementia, suggesting that exercise may con-

use due to ease of administration and interpretation, pa- tinue to provide benefits even after diagnosis [140]. A re-

tient-friendliness, sensitivity, specificity, and freedom cent review of lifestyle activities suggests that social net-

from factors such as age, education, and language [116]. working, in addition to mental and physical activity, is

A recently developed questionnaire called the St. Louis also important to maintaining cognitive health [141].

University Mental Status Examination, similar to the Therefore, patients should be encouraged to maintain or

MMSE but possibly more sensitive to MCI [117], also initiate healthy lifestyles, including a balanced diet, in-

shows promise for diagnostic purposes, although addi- creased mental and physical activities, and regular social

tional validation is required. With the standardization of contact with peers and family members.

basic clinical evaluation tools, practitioners should be Finally, since patients with AD become increasingly

able to evaluate patients more easily, potentially enabling dependent on caregiver support as the disease progresses,

earlier diagnosis, staging, and treatment initiation. To a caregiver’s own well-being constitutes an important

emphasize the importance of early and accurate diagno- goal of disease management. In a recent study of 406

sis of dementia, an international working group has re- caregivers over 18 years, nursing home placement of pa-

cently proposed new diagnostic criteria for AD that in- tients with AD was delayed by an average of 557 days in

clude neuroimaging, biomarkers, and genetic evidence families that received enhanced caregiver support [142].

[118]. Several studies have shown that many types of interven-

tion (cognitive-behavioral therapy, counseling, daycare,

Patient and Caregiver Lifestyle training of care recipient, and multicomponent interven-

Lifestyle and environmental factors such as diet, edu- tions) can be beneficial for people who care for patients

cation, and occupational complexity have all been inves- with AD [142–147]. Caregiver psychotherapy (counsel-

tigated for correlations to AD [119]. For example, a retro- ing) and psychoeducational techniques such as caregiver

spective analysis of approximately 10,000 participants of stress and anger management, depression management,

a healthcare system in California showed that an in- and programs designed to help the caregiver recognize

creased adiposity (defined as the body mass index of at and minimize stressful situations for patients, have prov-

least 25) in midlife (40–45 years of age) is associated with en particularly effective [86, 87]. Caregivers should be di-

a significantly greater risk of developing AD or vascular rected to educational and support resources, such as the

dementia, in a manner independent of comorbidities Alzheimer’s Association website (http://www.alz.org),

[120, 121]. According to a Swedish study of twins, low which contains a large amount of information about local

education represents a risk factor for dementia indepen- resources, caregiver support, and patient care. The issue

dent of genetic influences [122]. Both of these findings are of caregiver burden has been largely overlooked until re-

mirrored by another Scandinavian study, which showed cently, and deserves the increased attention of healthcare

that future dementia could be significantly predicted by policy makers and physicians alike [148].

high age, low education, hypertension, hypercholesterol-

emia, and obesity [123]. In addition, epidemiological Optimizing Pharmacotherapy: Monotherapy

studies suggest that the regular consumption of food rich Patients with AD often discontinue treatment due to

in antioxidants or -unsaturated fatty acids, such as red side effects, a lack of initial efficacy, or the loss (or per-

wine [124, 125], fruit and vegetable juices [126], green tea ceived loss) of efficacy during treatment [149]. Approxi-

414 Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008;25:408–422 Farlow /Miller /Pejovic

mately 51% of patients newly treated with an AD medica- rent practice suggests that patients should not discontin-

tion discontinue therapy within 4 months of treatment ue ChEI therapy even after they progress to a more severe

initiation [150], suggesting that many patients are not re- stage [155]. Additional studies involving patients with

ceiving optimal benefits from pharmacotherapy. The side mild-to-moderate AD may also help clarify whether me-

effects associated with the use of ChEIs, which are pri- mantine can be effective in treating patients (or a subset

marily gastrointestinal (table 2), continue to provide a of patients) in earlier stages of the disease [9, 41, 42].

significant challenge to patient adherence. Some of these Despite the apparent advantages of beginning therapy

adverse effects can be minimized through a slower dos- as early in the disease process as possible, the ability of

ing scheme (titrating as slowly as every 4–6 weeks) during either the ChEIs or memantine to delay (or modify) dis-

the initial and escalation phases of treatment, or by ad- ease progression, as opposed to merely providing symp-

ministering the medication with food to retard the rapid tomatic relief, remains unproven. The clinical efficacy of

stimulation of the cholinergic system [25] (except in the ChEIs in MCI is also being tested, but neither symptom-

case of donepezil and transdermally delivered rivastig- atic nor disease-modifying effects have been established

mine, for which the rate of absorption is not affected by for the use of these drugs at such an early stage [30, 59,

food [10, 151]). Since side effects associated with meman- 156, 157]. Preclinical studies with memantine are consis-

tine use are less severe and less frequent, tolerability prob- tent with a putative neuroprotective role [158], but this

lems are not a common reason for discontinuance with has yet to be demonstrated in patients. Until more data

this medication [4, 9]. are available, practicing physicians must use their best

As each ChEI has a distinct pharmacokinetic and judgment in determining the point at which pharmaco-

pharmacodynamic profile, switching patients from one therapy is instituted, based on an individual patient’s

ChEI to another is a viable option in patients who have risks and needs.

problems with long-term efficacy or tolerability of their

initial medication [149, 152]. In several studies, approxi- Optimizing Pharmacotherapy: Combination Therapy

mately 50% of patients who previously failed to respond Combination therapy is commonly used in treating

to a ChEI demonstrated stabilization or improvement af- many other diseases, including cancer and HIV. Due to

ter switching to a different ChEI; in addition, a patient’s the complex nature of AD and the distinct mechanisms of

response to one ChEI was not predictive of response to action of the ChEIs, memantine, and alternative treat-

another [5, 149, 152]. In many cases, patients who switch ments, combination therapy may also be effective in AD.

medications are also less likely to experience cholinergic

side effects [149]. The optimal procedure for switching Co-Administration of ChEIs and Memantine

remains to be determined, although some studies and A randomized, double-blind clinical trial of meman-

guidelines suggest that the second drug may be adminis- tine was performed in 404 patients with moderate-to-se-

tered as early as one day after the first has been discon- vere AD who were already receiving stable doses of done-

tinued [149]. In cases of poor tolerability with the initial- pezil [39]. Participants who received both donepezil and

ly prescribed medication, however, a washout period is memantine showed significantly better performance

recommended until side effects resolve [149]. One guide- over those who received donepezil plus placebo in all do-

line suggests cessation of therapy for five half-lives (done- mains assessed, which included measures of cognition,

pezil, 15 days; rivastigmine/galantamine, 2 days) before function (ADLs), behavior, psychiatric disturbance, and

switching [6], although in most cases 1 week is sufficient global condition. While most adverse events in both

[153]. Dose adjustments to the initial treatment should treatment groups were mild or moderate and judged to

always be considered before switching medications, and be unrelated to either study drug, the addition of meman-

a minimum treatment period of 6 months, with realistic tine was associated with a lower incidence of several cho-

treatment expectations (see below), is recommended in linergic adverse events in this study. Participants who re-

cases where a lack of efficacy is perceived [149]. ceived both drugs had a lower frequency of diarrhea, fecal

Traditionally, patients with early-stage (mild-to-mod- incontinence, and discontinuance due to adverse events

erate) AD are prescribed ChEIs, while memantine is in- than those on donepezil alone, although the statistical

dicated for patients in moderate-to-severe stages of the significance of these differences was not addressed in this

disease. These lines are beginning to blur, however. The study [39].

recent approval of donepezil for severe AD [154] will like- Pilot combination studies have also been performed

ly lead to increased ChEI use in late-stage AD, and cur- using memantine and the other ChEIs. A European post-

AD Treatment Options Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008;25:408–422 415

marketing surveillance study demonstrated that meman- results in clinical trials, it would be premature to recom-

tine is well-tolerated in combination with donepezil, riv- mend combining them with standard ChEI or meman-

astigmine, and tacrine [159]. Co-therapy of memantine tine therapy. Although these and other agents may even-

with galantamine in a 6-month prospective cross-sec- tually be deemed effective and safe for patients with AD,

tional study was well-tolerated and resulted in no cogni- additional prospective trials will be required to deter-

tive or functional deterioration during the course of mine their exact role in pharmacotherapy. However, there

treatment, according to caregiver reports [160]. Another is an increasing body of evidence that nonpharmacologi-

recent pilot study investigating the efficacy and tolerabil- cal methods may ultimately become a useful supplement

ity of memantine in patients with mild-to-moderate AD to current pharmacologic treatment. For example, a ran-

receiving stable rivastigmine treatment concluded that domized, controlled, multicenter trial of reality orienta-

the addition of memantine resulted in additional cogni- tion therapy in patients taking donepezil demonstrated

tive benefits and was safe and well-tolerated [161]. A significant improvements for patients receiving both

growing body of evidence suggests that adding meman- treatments over those receiving donepezil alone [169]. As

tine to ChEI therapy may produce additional cognitive, cognitive and behavioral methods pose little risk to pa-

functional, and global benefits, accompanied by a negli- tients and caregivers, and may provide benefits, caregiv-

gible increase in risk of adverse effects. The possibility ers should be encouraged to pursue these alternative

that memantine may also have an effect on improving the strategies if desired. However, more rigorously controlled

tolerability of ChEI treatment [39] merits further investi- long-term studies will be required to determine which of

gation in prospective trials. It should again be noted, these techniques, if any, can provide consistent benefits,

however, that memantine is currently approved for pa- and whether they should become a routine part of stan-

tients with moderate to severe AD, while rivastigmine dard therapy.

and galantamine are currently approved for patients with

mild to moderate AD.

Managing Expectations

Co-Administration of Antidementia Therapy and

Antipsychotics Unrealistic expectations of patients and caregivers can

While co-administration of ChEIs or memantine with negatively impact treatment compliance. When patients

antipsychotics and antidepressants is a standard practice inevitably continue to decline despite therapeutic inter-

for patients with behavioral disturbances in advanced vention, frustration is understandable; however, studies

stages of AD [24], the treatment of behavioral symptoms suggest that the benefits of therapy can be rapidly lost if

with atypical antipsychotics is considered off-label in ge- treatment is discontinued [170], and in most cases even

riatric patients, as these drugs are associated with an in- modest therapeutic effects provide justification for ther-

creased risk of death, falls and cerebrovascular adverse apy maintenance [155]. Open-label extension trials have

events in the elderly [162–164]. In such patients, nonphar- suggested continued benefits for up to 1 year with me-

macologic interventions should be exhausted prior to mantine [171] and for at least 3 years with each of the

prescribing drugs for these symptoms [for a review of ChEIs [172–174]. Patients and caregivers should be aware

many nonpharmacologic options, see 165]. Evidence also that current pharmacotherapy responses are less than

suggests that both memantine and the ChEIs may reduce ideal, and expectations should center on slowing decline

or prevent the emergence of behavioral symptoms in AD or delaying institutionalization rather than overall pa-

patients [37, 166, 167], which may allow patients to either tient improvement. While current treatments for AD

avert or reduce the usage of antipsychotic medications. It may lessen the symptomatic decline of the disease and

has been suggested that AD patients are particularly vul- provide an extension of independence in some cases, they

nerable to antipsychotic-induced cerebral neurotoxicity, cannot be considered disease-modifying or curative.

so diminished antipsychotic use may be of particular rel- Physicians must exercise caution when discussing treat-

evance in this patient population [168]. ments with patients and their caregivers, impressing

upon them that the benefits of current pharmacologic

Co-Administration of Traditional and treatments are rarely seen as an improvement in symp-

Nontraditional Therapies toms, but rather as an extension of patient independence.

As studies regarding the efficacy of agents such as vi- If patients and caregivers understand that a significant

tamin E and G. biloba have not yet produced consistent goal of treatment is to delay the onset of more severe

416 Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008;25:408–422 Farlow /Miller /Pejovic

symptoms or long-term care placement, treatment com- first line of pharmacotherapy for mild-to-moderate AD,

pliance may improve. Providing regular reassessment ev- while memantine and donepezil are both indicated for

ery 6 months is also crucial for tracking both the progres- moderate-to-severe AD. In instances where patients do

sion of the disease and the status of the caregiver [175]. not respond or have tolerability issues with a particular

Physicians should also assist patients and caregivers ChEI, changes in dose titration or switching of ChEIs can

in recognizing that nontraditional treatments, such as be attempted. Combinations involving memantine and

ginkgo, vitamin E, and selegiline, are not yet clinically ChEIs may produce additional benefits to patients with-

validated as efficacious treatments. While some clinical out significantly increasing the risk of side effects, and

evidence supports their use, many of the double-blind future clinical trials may identify other agents that show

placebo-controlled trials to date have been negative. Con- efficacy for AD symptoms when used alone or as a part

tinuing the prescribed treatment – along with a healthy of combination therapy. In principle, therapeutic inter-

diet, exercise (if possible), and regular contact with the vention should occur early in the disease, in order to slow

physician – is the most realistic manner in which patients or prevent symptom progression for as long as possible.

can control the symptoms of their illness. Patients and caregivers must maintain reasonable ex-

pectations regarding pharmacotherapy, and resources

such as support groups and social networking can pro-

Conclusions vide relief for both patients and caregivers. Cognitive and

behavioral therapies may also play a role in improving

The availability of approved pharmacotherapies (sec- patient cognition and function, diminishing caregiver

ond-generation ChEIs and memantine) and the emer- stress, and delaying nursing home placement. As more is

gence of numerous alternative therapies have armed phy- learned about the combinatorial effects of these and oth-

sicians with more treatment options for AD compared to er potential therapeutic options at all stages of AD, the

just over a decade ago, when tacrine was the only avail- ability to significantly impact disease progression may

able therapeutic option. Although prospective trials ex- one day be realized.

amining the role of agents such as NSAIDs, selegiline or

estrogen-progestin combination in the prevention or

treatment of AD have been largely negative, potential Acknowledgments

new therapeutics for AD, including statins and agents

The authors wish to thank Ms. Annalise Nawrocki and Dr.

that combat amyloid deposition and tau hyperphosphor-

Kristen A. Andersen of Prescott Medical Communications Group

ylation, may one day be shown to provide protection for their assistance in the preparation and review of the manu-

against neurodegeneration. However, until new preven- script.

tive or disease-altering medications are approved, physi- Dr. Martin Farlow receives support from the NIH grant P30

cians must optimize the use of available pharmaceutical AG10133.

and behavioral therapies. ChEIs are still the traditional

References

1 Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, Bennett 4 Birks J: Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alz- 6 Cummings JL: Use of cholinesterase inhibi-

DA, Evans DA: Alzheimer disease in the US heimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst tors in clinical practice: evidence-based rec-

population: prevalence estimates using the Rev 2006:CD005593. ommendations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry

2000 census. Arch Neurol 2003; 60: 1119– 5 Burns A, O’Brien J, Auriacombe S, Ballard C, 2003;11:131–145.

1122. Broich K, Bullock R, Feldman H, Ford G, 7 Farlow M: A clinical overview of cholinester-

2 Hebert LE, Beckett LA, Scherr PA, Evans Knapp M, McCaddon A, Iliffe S, Jacova C, ase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease. Int

DA: Annual incidence of Alzheimer disease Jones R, Lennon S, McKeith I, Orgogozo JM, Psychogeriatr 2002;14(suppl 1):93–126.

in the United States projected to the years Purandare N, Richardson M, Ritchie C, 8 Farlow MR: Utilizing combination therapy

2000 through 2050. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Thomas A, Warner J, Wilcock G, Wilkinson in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Ex-

Disord 2001;15:169–173. D: Clinical practice with anti-dementia pert Rev Neurotherapeutics 2004; 4: 799–

3 Wancata J, Musalek M, Alexandrowicz R, drugs: a consensus statement from British 808.

Krautgartner M: Number of dementia suf- Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psy- 9 McShane R, Areosa Sastre A, Minakaran N:

ferers in Europe between the years 2000 and chopharmacol 2006;20:732–755. Memantine for dementia. Cochrane Data-

2050. Eur Psychiatry 2003;18:306–313. base Syst Rev 2006:CD003154.

AD Treatment Options Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008;25:408–422 417

10 Aricept쏐: U.S. Prescribing Information. 27 Exelon Patch쏐: U.S. Prescribing Informa- 41 Peskind ER, Potkin SG, Pomara N, Ott BR,

New York, Pfizer, 2006. tion. East Hanover, Novartis, 2007. Graham SM, Olin JT, McDonald S, for the

11 Dunn NR: Adverse effects associated with 28 Razadyne ER: U.S. Prescribing Informa- Memantine MEM-MD-10 Study Group:

the use of donepezil in general practice in tion. Titusville, Ortho-McNeil Neurologics, Memantine treatment in mild to moderate

England. J Psychopharmacol 2000; 14: 406– 2006. Alzheimer disease: a 24-week randomized,

448. 29 Maelicke A, Albuquerque EX: Allosteric controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry

12 Tiseo PJ, Perdomo CA, Friedhoff LT: Metab- modulation of nicotinic acetylcholine recep- 2006;14:704–715.

olism and elimination of 14C-donepezil in tors as a treatment strategy for Alzheimer’s 42 Doody RS, Tariot PN, Pfeiffer E, Olin J, Gra-

healthy volunteers: a single-dose study. Br J disease. Eur J Pharmacol 2000;393:165–170. ham SM: Meta-analysis of 6-month meman-

Clin Pharmacol 1998;46(suppl 1):19–24. 30 Loy C, Schneider L: Galantamine for Alz- tine trials in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer

13 Seltzer B: Donepezil: a review. Expert Opin heimer’s disease and mild cognitive impair- Dement 2007;3:7–17.

Drug Metab Toxicol 2005;1:527–536. ment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006: 43 Micuda S, Mundlova L, Anzenbacherova E,

14 Exelon: U.S. Prescribing Information. East CD001747. Anzenbacher P, Chladek J, Fuksa L, Mar-

Hanover, Novartis, 2006. 31 Mannens GS, Snel CA, Hendrickx J, Verhae- tinkova J: Inhibitory effects of memantine

15 Bullock R: The clinical benefits of rivastig- ghe T, Le Jeune L, Bode W, van Beijsterveldt on human cytochrome P450 activities: pre-

mine may reflect its dual inhibitory mode of L, Lavrijsen K, Leempoels J, Van Osselaer N, diction of in vivo drug interactions. Eur J

action: an hypothesis. Int J Clin Pract 2002; Van Peer A, Meuldermans W: The metabo- Clin Pharmacol 2004;60:583–589.

56:206–214. lism and excretion of galantamine in rats, 44 Periclou A, Ventura D, Rao N, Abramowitz

16 Giacobini E: Cholinesterase inhibitors: new dogs, and humans. Drug Metab Dispos 2002; W: Pharmacokinetic study of memantine in

roles and therapeutic alternatives. Pharma- 30:553–563. healthy and renally impaired subjects. Clin

col Res 2004;50:433–440. 32 Namenda쏐: U.S. Prescribing Information. Pharmacol Ther 2006;79:134–143.

17 Giacobini E: Cholinesterases: new roles in St. Louis, Forest Pharmaceuticals, 2006. 45 van Gool WA, Aisen PS, Eikelenboom P:

brain function and in Alzheimer’s disease. 33 Arundine M, Tymianski M: Molecular Anti-inflammatory therapy in Alzheimer’s

Neurochem Res 2003;28:515–522. mechanisms of calcium-dependent neuro- disease: is hope still alive? J Neurol 2003;250:

18 Kuhl DE, Koeppe RA, Snyder SE, Minoshi- degeneration in excitotoxicity. Cell Calcium 788–792.

ma S, Frey KA, Kilbourn MR: In vivo butyr- 2003;34:325–337. 46 McGeer PL, Rogers J, McGeer EG: Inflam-

ylcholinesterase activity is not increased in 34 Danysz W, Parsons C, Möbius HJ, Stöffler A, mation, anti-inflammatory agents and Alz-

Alzheimer’s disease synapses. Ann Neurol Quack G: Neuroprotective and symptomat- heimer disease: the last 12 years. J Alzhei-

2006;59:13–20. ological action of memantine relevant for mers Dis 2006;9:271–276.

19 Exelon쏐: U.S. Prescribing Information. East Alzheimer’s disease – a unified glutamater- 47 in t’ Veld BA, Ruitenberg A, Hofman A,

Hanover, Novartis, 2006. gic hypothesis on the mechanism of action. Launer LJ, van Duijn CM, Stijnen T, Breteler

20 Farlow MR: Update on rivastigmine. Neu- Neurotox Res 1999;2:85–97. MM, Stricker BH: Nonsteroidal antiinflam-

rologist 2003; 9:230–234. 35 Rogawski MA, Wenk GL: The neurophar- matory drugs and the risk of Alzheimer’s

21 Gobburu JV, Tammara V, Lesko L, Jhee SS, macological basis for the use of memantine disease. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1515–1521.

Sramek JJ, Cutler NR, Yuan R: Pharmacoki- in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. CNS 48 Zandi PP, Breitner JC: Do NSAIDs prevent

netic-pharmacodynamic modeling of riv- Drug Rev 2003;9:275–308. Alzheimer’s disease? And, if so, why? The

astigmine, a cholinesterase inhibitor, in pa- 36 Cummings JL, Schneider E, Tariot PN, Gra- epidemiological evidence. Neurobiol Aging

tients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin ham SM: Behavioral effects of memantine in 2001;22:811–817.

Pharmacol 2001;41:1082–1090. Alzheimer disease patients receiving done- 49 Aisen PS, Schafer KA, Grundman M, Pfeif-

22 Birks J, Grimley Evans J, Iakovidou V, Tso- pezil treatment. Neurology 2006;67:57–63. fer E, Sano M, Davis KL, Farlow MR, Jin S,

laki M: Rivastigmine for Alzheimer’s dis- 37 Gauthier S, Wirth Y, Mobius HJ: Effects of Thomas RG, Thal LJ: Effects of rofecoxib or

ease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000: memantine on behavioural symptoms in naproxen vs. placebo on Alzheimer disease

CD001191. Alzheimer’s disease patients: an analysis of progression: a randomized controlled trial.

23 Suh DC, Arcona S, Thomas SK, Powers C, the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) data JAMA 2003;289:2819–2826.

Rabinowicz AL, Shin H, Mirski D: Risk of two randomised, controlled studies. Int J 50 Thal LJ, Ferris SH, Kirby L, Block GA, Lines

of antipsychotic drug use in patients with Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;20:459–464. CR, Yuen E, Assaid C, Nessly ML, Norman

Alzheimer’s disease treated with rivastig- 38 Reisberg B, Doody R, Stöffler A, Schmitt F, BA, Baranak CC, Reines SA: A randomized,

mine. Drugs Aging 2004;21:395–403. Ferris S, Möbius HJ: Memantine in moder- double-blind, study of rofecoxib in patients

24 Doody RS, Stevens JC, Beck C, Dubinsky ate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J with mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsy-

RM, Kaye JA, Gwyther L, Mohs RC, Thal LJ, Med 2003;348:1333–1341. chopharmacology 2005;30:1204–1215.

Whitehouse PJ, DeKosky ST, Cummings JL: 39 Tariot PN, Farlow MR, Grossberg GT, Gra- 51 Jelic V, Kivipelto M, Winblad B: Clinical tri-

Practice parameter: management of demen- ham SM, McDonald S, Gergel I: Memantine als in mild cognitive impairment: lessons for

tia (an evidence-based review). Report of the treatment in patients with moderate to se- the future. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry

Quality Standards Subcommittee of the vere Alzheimer disease already receiving 2006;77:429–438.

American Academy of Neurology. Neurolo- donepezil: a randomized controlled trial. 52 U.S. Food and Drug Administration: FDA

gy 2001;56:1154–1166. JAMA 2004;291:317–324. Issues Public Health Advisory Recommend-

25 Jann MW, Shirley KL, Small GW: Clinical 40 Winblad B, Poritis N: Memantine in severe ing Limited Use of Cox-2 Inhibitors. FDA

pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics dementia: results of the M-Best Study (Ben- Talk Paper, December 23. 2004;T04-61.

of cholinesterase inhibitors. Clin Pharmaco- efit and efficacy in severely demented pa- 53 Pratico D, Delanty N: Oxidative injury in

kinet 2002;41:719–739. tients during treatment with memantine). diseases of the central nervous system: focus

26 Winblad B, Cummings JL, et al: IDEAL: a 24 Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1999;14:135–146. on Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Med 2000;109:

week placebo controlled study of the first 577–585.

transdermal patch in Alzheimer’s disease – 54 Markesbery WR, Carney JM: Oxidative al-

rivastigmine patch versus capsule; presented terations in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain

at the 10th International Congress of Alz- Pathol 1999;9:133–146.

heimer’s and Related Disorders (ICAD), Ma-

drid, Spain, 2006.

418 Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008;25:408–422 Farlow /Miller /Pejovic

55 Nourhashemi F, Gillette-Guyonnet S, 68 Mazza M, Capuano A, Bria P, Mazza S: Gink- 79 Simons M, Schwarzler F, Lutjohann D, von

Andrieu S, Ghisolfi A, Ousset PJ, Grandjean go biloba and donepezil: a comparison in the Bergmann K, Beyreuther K, Dichgans J,

H, Grand A, Pous J, Vellas B, Albarede JL: treatment of Alzheimer’s dementia in a ran- Wormstall H, Hartmann T, Schulz JB: Treat-

Alzheimer disease: protective factors. Am J domized placebo-controlled double-blind ment with simvastatin in normocholester-

Clin Nutr 2000;71:643S–649S. study. Eur J Neurol 2006;13:981–985. olemic patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a

56 Luchsinger JA, Tang MX, Shea S, Mayeux 69 Schneider LS, DeKosky ST, Farlow MR, Tar- 26-week randomized, placebo-controlled,

R: Antioxidant vitamin intake and risk of iot PN, Hoerr R, Kieser M: A randomized, double-blind trial. Ann Neurol 2002; 52:

Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2003; 60: double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of two 346–350.

203–208. doses of Ginkgo biloba extract in dementia of 80 Sparks DL, Sabbagh MN, Connor DJ, Lopez

57 Morris MC, Beckett LA, Scherr PA, Hebert the Alzheimer’s type. Curr Alzheimer Res J, Launer LJ, Browne P, Wasser D, Johnson-

LE, Bennett DA, Field TS, Evans DA: Vita- 2005;2:541–551. Traver S, Lochhead J, Ziolwolski C: Atorva-

min E and vitamin C supplement use and 70 Sierpina V, Wollschlaeger B, Blumenthal M: statin for the treatment of mild to moderate

risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Alzhei- Ginkgo biloba. Am Fam Physician 2003; 68: Alzheimer disease: preliminary results. Arch

mer Dis Assoc Disord 1998;12:121–126. 923–926. Neurol 2005;62:753–757.

58 Sano M, Ernesto C, Thomas RG, Klauber 71 Nelson HD, Humphrey LL, Nygren P, 81 Algotsson A, Winblad B: Patients with Alz-

MR, Schafer K, Grundman M, Woodbury Teutsch SM, Allan JD: Postmenopausal hor- heimer’s disease may be particularly suscep-

P, Growdon J, Cotman CW, Pfeiffer E, mone replacement therapy: scientific review. tible to adverse effects of statins. Dement

Schneider LS, Thal LJ: A controlled trial JAMA 2002;288:872–881. Geriatr Cogn Disord 2004;17:109–116.

of selegiline, alpha-tocopherol, or both as 72 Shumaker SA, Legault C, Thal L, Wallace 82 Yon A, Scogin F: Procedures for identifying

treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. The Alz- RB, Ockene JK, Hendrix SL, Jones BN 3rd, evidence-based psychological treatments for

heimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. N Engl Assaf AR, Jackson RD, Kotchen JM, Was- older adults. Psychol Aging 2007; 22:4–7.

J Med 1997;336:1216–1222. sertheil-Smoller S, Wactawski-Wende J: Es- 83 Sitzer DI, Twamley EW, Jeste DV: Cognitive

59 Petersen RC, Thomas RG, Grundman M, trogen plus progestin and the incidence training in Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-anal-

Bennett D, Doody R, Ferris S, Galasko D, Jin of dementia and mild cognitive impairment ysis of the literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand

S, Kaye J, Levey A, Pfeiffer E, Sano M, van in postmenopausal women: the Women’s 2006;114:75–90.

Dyck CH, Thal LJ: Vitamin E and donepezil Health Initiative Memory Study: a random- 84 Spector A, Orrell M, Davies S, Woods B: Re-

for the treatment of mild cognitive impair- ized controlled trial. JAMA 2003; 289: 2651– ality orientation for dementia. Cochrane Da-

ment. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2379–2388. 2662. tabase Syst Rev 2000:CD001119.

60 Miller ER 3rd, Pastor-Barriuso R, Dalal D, 73 Rapp SR, Espeland MA, Shumaker SA, Hen- 85 Spector A, Thorgrimsen L, Woods B, Royan

Riemersma RA, Appel LJ, Guallar E: Meta- derson VW, Brunner RL, Manson JE, Gass L, Davies S, Butterworth M, Orrell M: Effi-

analysis: high-dosage vitamin E supplemen- ML, Stefanick ML, Lane DS, Hays J, Johnson cacy of an evidence-based cognitive stimula-

tation may increase all-cause mortality. Ann KC, Coker LH, Dailey M, Bowen D: Effect of tion therapy programme for people with de-

Intern Med 2005;142:37–46. estrogen plus progestin on global cognitive mentia: randomised controlled trial. Br J

61 Lange KW, Riederer P, Youdim MB: Bio- function in postmenopausal women: the Psychiatry 2003;183:248–254.

chemical actions of l-deprenyl (selegiline). Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a 86 Logsdon RG, McCurry SM, Teri L: Evidence-

Clin Pharmacol Ther 1994;56:734–741. randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003; based psychological treatments for disrup-

62 Filip V, Kolibas E: Selegiline in the treatment 289:2663–2672. tive behaviors in individuals with dementia.

of Alzheimer’s disease: a long-term random- 74 Chlebowski RT, Hendrix SL, Langer RD, Ste- Psychol Aging 2007;22:28–36.

ized placebo-controlled trial. Czech and Slo- fanick ML, Gass M, Lane D, Rodabough 87 Gallagher-Thompson D, Coon DW: Evi-

vak Senile Dementia of Alzheimer Type RJ, Gilligan MA, Cyr MG, Thomson CA, dence-based psychological treatments for

Study Group. J Psychiatry Neurosci 1999;24: Khandekar J, Petrovitch H, McTiernan A: distress in family caregivers of older adults.

234–243. Influence of estrogen plus progestin on Psychol Aging 2007;22:37–51.

63 Birks J, Flicker L: Selegiline for Alzheimer’s breast cancer and mammography in healthy 88 Gomez-Isla T, Price JL, McKeel DW Jr, Mor-

disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003: postmenopausal women: the Women’s ris JC, Growdon JH, Hyman BT: Profound

CD000442. Health Initiative Randomized Trial. JAMA loss of layer II entorhinal cortex neurons oc-

64 Wold RS, Lopez ST, Yau CL, Butler LM, 2003;289:3243–3253. curs in very mild Alzheimer’s disease. J Neu-

Pareo-Tubbeh SL, Waters DL, Garry PJ, 75 Wassertheil-Smoller S, Hendrix SL, Lima- rosci 1996;16:4491–4500.

Baumgartner RN: Increasing trends in elder- cher M, Heiss G, Kooperberg C, Baird A, 89 Morris JC, Storandt M, McKeel DW Jr, Rubin

ly persons’ use of nonvitamin, nonmineral Kotchen T, Curb JD, Black H, Rossouw JE, EH, Price JL, Grant EA, Berg L: Cerebral

dietary supplements and concurrent use of Aragaki A, Safford M, Stein E, Laowattana S, amyloid deposition and diffuse plaques in

medications. J Am Diet Assoc 2005;105:54– Mysiw WJ: Effect of estrogen plus progestin ‘normal’ aging: evidence for presymptom-

63. on stroke in postmenopausal women: the atic and very mild Alzheimer’s disease. Neu-

65 Ahlemeyer B, Krieglstein J: Neuroprotective Women’s Health Initiative: a randomized rology 1996; 46:707–719.

effects of Ginkgo biloba extract. Cell Mol Life trial. JAMA 2003;289:2673–2684. 90 Mondadori CR, Buchmann A, Mustovic H,

Sci 2003;60:1779–1792. 76 MacLennan AH, Henderson VW, Paine BJ, Schmidt CF, Boesiger P, Nitsch RM, Hock C,

66 Birks J, Grimley E, van Dongen M: Ginkgo Mathias J, Ramsay EN, Ryan P, Stocks NP, Streffer J, Henke K: Enhanced brain activity

biloba for cognitive impairment and demen- Taylor AW: Hormone therapy, timing of ini- may precede the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s

tia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002; 4: tiation, and cognition in women aged older disease by 30 years. Brain 2006; 129: 2908–

CD003120. than 60 years: the REMEMBER pilot study. 2922.

67 Napryeyenko O, Borzenko I: Ginkgo biloba Menopause 2006;13:28–36. 91 Ingelsson M, Fukumoto H, Newell KL,

special extract in dementia with neuropsy- 77 Miida T, Takahashi A, Tanabe N, Ikeuchi T: Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Frosch MP,

chiatric features. A randomised, placebo- Can statin therapy really reduce the risk of Albert MS, Hyman BT, Irizarry MC: Early

controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Arz- Alzheimer’s disease and slow its progres- Abeta accumulation and progressive synap-

neimittelforschung 2007;57:4–11. sion? Curr Opin Lipidol 2005; 16:619–623. tic loss, gliosis, and tangle formation in AD

78 Drachman D: Preventing and treating Alz- brain. Neurology 2004;62:925–931.

heimer’s disease: strategies and prospects.

Exp Rev Neurotherapeut 2003;3:565–569.

AD Treatment Options Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008;25:408–422 419

92 DeKosky S: Early intervention is key to suc- 103 Petersen RC, Doody R, Kurz A, Mohs RC, 117 Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, Perry

cessful management of Alzheimer disease. Morris JC, Rabins PV, Ritchie K, Rossor M, MH 3rd, Morley JE: Comparison of the

Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2003;17(suppl Thal L, Winblad B: Current concepts in Saint Louis University Mental Status Ex-

4):S99–S104. mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol amination and the Mini-Mental State Ex-

93 Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, 2001;58:1985–1992. amination for detecting dementia and mild

Fratiglioni L, Wahlund LO, Nordberg A, 104 Daly E, Zaitchik D, Copeland M, Schmah- neurocognitive disorder – a pilot study. Am

Backman L, Albert M, Almkvist O, Arai H, mann J, Gunther J, Albert M: Predicting J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;14:900–910.

Basun H, Blennow K, de Leon M, DeCarli conversion to Alzheimer disease using 118 Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Dekosky

C, Erkinjuntti T, Giacobini E, Graff C, Har- standardized clinical information. Arch ST, Barberger-Gateau P, Cummings J, Dela-

dy J, Jack C, Jorm A, Ritchie K, van Duijn Neurol 2000;57:675–680. courte A, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Jicha G,

C, Visser P, Petersen RC: Mild cognitive im- 105 Garand L, Dew MA, Eazor LR, DeKosky Meguro K, O’Brien J, Pasquier F, Robert P,

pairment – beyond controversies, towards ST, Reynolds CF 3rd: Caregiving burden Rossor M, Salloway S, Stern Y, Visser PJ,

a consensus: report of the International and psychiatric morbidity in spouses of Scheltens P: Research criteria for the diag-

Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impair- persons with mild cognitive impairment. nosis of Alzheimer’s disease: revising the

ment. J Intern Med 2004;256:240–246. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;20:512–522. NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurol

94 Petersen RC: Mild cognitive impairment as 106 Ready RE, Ott BR, Grace J: Patient versus 2007;6:734–746.

a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med 2004; 256: informant perspectives of Quality of Life in 119 Gatz M, Prescott CA, Pedersen NL: Life-

183–194. Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzhei- style risk and delaying factors. Alzheimer

95 Gauthier S, Reisberg B, Zaudig M, Petersen mer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2004; Dis Assoc Disord 2006;20:S84–S88.

RC, Ritchie K, Broich K, Belleville S, Bro- 19:256–265. 120 Whitmer RA, Gunderson EP, Barrett-Con-

daty H, Bennett D, Chertkow H, Cum- 107 Olazaran J, Muniz R, Reisberg B, Pena-Ca- nor E, Quesenberry CP Jr, Yaffe K: Obesity

mings JL, de Leon M, Feldman H, Ganguli sanova J, del Ser T, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Serrano in middle age and future risk of dementia:

M, Hampel H, Scheltens P, Tierney MC, P, Navarro E, Garcia de la Rocha ML, Frank a 27 year longitudinal population based

Whitehouse P, Winblad B: Mild cognitive A, Galiano M, Fernandez-Bullido Y, Serra study. BMJ 2005;330:1360.

impairment. Lancet 2006;367:1262–1270. JA, Gonzalez-Salvador MT, Sevilla C: Ben- 121 Whitmer RA, Gunderson EP, Quesenberry

96 Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik efits of cognitive-motor intervention in CP Jr, Zhou J, Yaffe K: Body mass index in

RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E: Mild cognitive MCI and mild to moderate Alzheimer dis- midlife and risk of Alzheimer disease and

impairment: clinical characterization and ease. Neurology 2004;63:2348–2353. vascular dementia. Curr Alzheimer Res

outcome. Arch Neurol 1999;56:303–308. 108 Ready RE, Ott BR, Grace J: Validity of in- 2007;4:103–109.

97 Fischer P, Jungwirth S, Zehetmayer S, formant reports about AD and MCI pa- 122 Gatz M, Mortimer JA, Fratiglioni L, Jo-

Weissgram S, Hoenigschnabl S, Gelpi E, tients’ memory. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Dis- hansson B, Berg S, Andel R, Crowe M, Fiske

Krampla W, Tragl KH: Conversion from ord 2004;18:11–16. A, Reynolds CA, Pedersen NL: Accounting

subtypes of mild cognitive impairment to 109 Scheltens P, Korf ES: Contribution of neu- for the relationship between low education

Alzheimer dementia. Neurology 2007; 68: roimaging in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s and dementia: a twin study. Physiol Behav

288–291. disease and other dementias. Curr Opin 2007;92:232–237.

98 Tabert MH, Manly JJ, Liu X, Pelton GH, Neurol 2000;13:391–396. 123 Kivipelto M, Ngandu T, Laatikainen T,

Rosenblum S, Jacobs M, Zamora D, Good- 110 Chang CY, Silverman DH: Accuracy of ear- Winblad B, Soininen H, Tuomilehto J: Risk

kind M, Bell K, Stern Y, Devanand DP: ly diagnosis and its impact on the manage- score for the prediction of dementia risk in

Neuropsychological prediction of conver- ment and course of Alzheimer’s disease. 20 years among middle aged people: a lon-

sion to Alzheimer disease in patients with Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2004;4:63–69. gitudinal, population-based study. Lancet

mild cognitive impairment. Arch Gen Psy- 111 Dougall NJ, Bruggink S, Ebmeier KP: Sys- Neurol 2006;5:735–741.

chiatry 2006;63:916–924. tematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of 124 Orgogozo JM, Dartigues JF, Lafont S,

99 Palmer K, Berger AK, Monastero R, Win- 99mTc-HMPAO-SPECT in dementia. Am J Letenneur L, Commenges D, Salamon R,

blad B, Backman L, Fratiglioni L: Predic- Geriatr Psychiatry 2004;12:554–570. Renaud S, Breteler MB: Wine consumption

tors of progression from mild cognitive im- 112 Kantarci K, Jack CR Jr: Neuroimaging in and dementia in the elderly: a prospective

pairment to Alzheimer disease. Neurology Alzheimer disease: an evidence-based re- community study in the Bordeaux area.

2007;68:1596–1602. view. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2003; 13: Rev Neurol (Paris) 1997;153:185–192.

100 Lopez OL, Kuller LH, Becker JT, Dulberg C, 197–209. 125 Anekonda TS: Resveratrol – a boon for

Sweet RA, Gach HM, Dekosky ST: Incidence 113 Silverman DH, Gambhir SS, Huang HW, treating Alzheimer’s disease? Brain Res

of dementia in mild cognitive impairment in Schwimmer J, Kim S, Small GW, Chodosh Brain Res Rev 2006;52:316–326.

the cardiovascular health study cognition J, Czernin J, Phelps ME: Evaluating early 126 Dai Q, Borenstein AR, Wu Y, Jackson JC,

study. Arch Neurol 2007;64:416–420. dementia with and without assessment of Larson EB: Fruit and vegetable juices and

101 Schonknecht P, Pantel J, Kaiser E, Tho- regional cerebral metabolism by PET: a Alzheimer’s disease: the Kame Project. Am

mann P, Schroder J: Increased tau protein comparison of predicted costs and benefits. J Med 2006;119:751–759.

differentiates mild cognitive impairment J Nucl Med 2002;43:253–266. 127 Rezai-Zadeh K, Shytle D, Sun N, Mori T,

from geriatric depression and predicts con- 114 McMahon PM, Araki SS, Sandberg EA, Hou H, Jeanniton D, Ehrhart J, Townsend

version to dementia. Neurosci Lett 2007; Neumann PJ, Gazelle GS: Cost-effective- K, Zeng J, Morgan D, Hardy J, Town T, Tan

416:39–42. ness of PET in the diagnosis of Alzheimer J: Green tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate

102 Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Dekosky disease. Radiology 2003;228: 515–522. (EGCG) modulates amyloid precursor pro-

ST, Barberger-Gateau P, Cummings J, Dela- 115 McMahon PM, Araki SS, Neumann PJ, tein cleavage and reduces cerebral amyloi-

courte A, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Jicha G, Harris GJ, Gazelle GS: Cost-effectiveness of dosis in Alzheimer transgenic mice. J Neu-

Meguro K, O’Brien J, Pasquier F, Robert P, functional imaging tests in the diagnosis of rosci 2005;25:8807–8814.

Rossor M, Salloway S, Stern Y, Visser PJ, Alzheimer disease. Radiology 2000; 217:

Scheltens P: Research criteria for the diag- 58–68.

nosis of Alzheimer’s disease: revising the 116 Lorentz WJ, Scanlan JM, Borson S: Brief

NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurol screening tests for dementia. Can J Psychia-

2007;6:734–746. try 2002;47:723–733.

420 Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008;25:408–422 Farlow /Miller /Pejovic

128 Arendash GW, Schleif W, Rezai-Zadeh K, 141 Fratiglioni L, Paillard-Borg S, Winblad B: 154 Winblad B, Kilander L, Eriksson S, Mint-

Jackson EK, Zacharia LC, Cracchiolo JR, An active and socially integrated lifestyle in hon L, Batsman S, Wetterholm AL, Jans-

Shippy D, Tan J: Caffeine protects Alzhei- late life might protect against dementia. son-Blixt C, Haglund A: Donepezil in pa-

mer’s mice against cognitive impairment Lancet Neurol 2004;3:343–353. tients with severe Alzheimer’s disease:

and reduces brain beta-amyloid produc- 142 Mittelman MS, Haley WE, Clay OJ, Roth double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-

tion. Neuroscience 2006;142:941–952. DL: Improving caregiver well-being delays controlled study. Lancet 2006; 367: 1057–

129 Lindsay J, Laurin D, Verreault R, Hebert R, nursing home placement of patients with 1065.

Helliwell B, Hill GB, McDowell I: Risk fac- Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2006; 67: 155 Schmitt FA, Wichems CH: A systematic re-

tors for Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective 1592–1599. view of assessment and treatment of mod-

analysis from the Canadian Study of Health 143 Mittelman MS, Roth DL, Haley WE, Zarit erate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Prim

and Aging. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 156:445– SH: Effects of a caregiver intervention on Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 8:

453. negative caregiver appraisals of behavior 158–159.

130 Lim GP, Chu T, Yang F, Beech W, Frautschy problems in patients with Alzheimer’s dis- 156 Feldman HH, Ferris S, Winblad B, Sfikas

SA, Cole GM: The curry spice curcumin re- ease: results of a randomized trial. J Geron- N, Mancione L, He Y, Tekin S, Burns A,

duces oxidative damage and amyloid pa- tol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2004; 59:P27–P34. Cummings J, del Ser T, Inzitari D, Orgogo-

thology in an Alzheimer transgenic mouse. 144 Roth DL, Mittelman MS, Clay OJ, Madan zo JM, Sauer H, Scheltens P, Scarpini E,

J Neurosci 2001;21:8370–8377. A, Haley WE: Changes in social support as Herrmann N, Farlow M, Potkin S, Charles

131 Yang F, Lim GP, Begum AN, Ubeda OJ, mediators of the impact of a psychosocial HC, Fox NC, Lane R: Effect of rivastigmine

Simmons MR, Ambegaokar SS, Chen PP, intervention for spouse caregivers of per- on delay to diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dis-

Kayed R, Glabe CG, Frautschy SA, Cole sons with Alzheimer’s disease. Psychol Ag- ease from mild cognitive impairment: the

GM: Curcumin inhibits formation of amy- ing 2005;20:634–644. InDDEx study. Lancet Neurol 2007; 6:501–

loid beta oligomers and fibrils, binds 145 Jang Y, Clay OJ, Roth DL, Haley WE, Mit- 512.

plaques, and reduces amyloid in vivo. J Biol telman MS: Neuroticism and longitudinal 157 Birks J, Flicker L: Donepezil for mild cogni-

Chem 2005;280:5892–5901. change in caregiver depression: impact of a tive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst

132 Morris MC, Evans DA, Bienias JL, Tangney spouse-caregiver intervention program. Rev 2006;3:CD006104.

CC, Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Aggarwal N, Gerontologist 2004; 44:311–317. 158 Lipton SA: Paradigm shift in neuroprotec-

Schneider J: Consumption of fish and n-3 146 Mittelman MS, Roth DL, Coon DW, Haley tion by NMDA receptor blockade: meman-

fatty acids and risk of incident Alzheimer WE: Sustained benefit of supportive inter- tine and beyond. Nat Rev Drug Discov

disease. Arch Neurol 2003;60:940–946. vention for depressive symptoms in care- 2006;5:160–170.

133 Morris MC, Evans DA, Tangney CC, Bien- givers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. 159 Hartmann S, Mobius HJ: Tolerability of

ias JL, Wilson RS: Fish consumption and Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:850–856. memantine in combination with cholines-

cognitive decline with age in a large com- 147 Belle SH, Burgio L, Burns R, Coon D, Czaja terase inhibitors in dementia therapy. Int