Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Reichenbach 2010

Uploaded by

EriC. ChaN.Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Reichenbach 2010

Uploaded by

EriC. ChaN.Copyright:

Available Formats

Extended report

Association of bone attrition with knee pain, stiffness

and disability: a cross-sectional study

Stephan Reichenbach,1,2 Paul A Dieppe,3 Eveline Nüesch,1,4 Susan Williams,5

Peter M Villiger,2 Peter Jüni1,4

1Division of Clinical Epidemiology ABSTRACT We recently described a simple method with

and Biostatistics, Institute of Objectives Bone pathologies as detected on MRI which to assess bone attrition at the knee joint on

Social and Preventive Medicine,

University of Bern, Switzerland are associated with the presence of pain in knee routine x-rays.14 Bone attrition was defined as a

2Department of Rheumatology, osteoarthritis (OA). The authors examined whether bone vertical loss of bone volume in the affected condyle.

Clinical Immunology, and attrition assessed on x-rays was associated with pain, Our data, derived from a cohort with advanced OA

Allergology, Bern University stiffness and disability. of the knee, suggested that bone attrition might be

Hospital, Switzerland related to night pain.14 Others have found subchon-

3Institute of Clinical Education Methods The authors analysed x-rays of 1326 knees

Research, Peninsula Medical with OA from 783 individuals participating in the dral bone marrow oedema as detected on MRI to

School, Universities of Exeter cross-sectional population-based Somerset and Avon be associated with pain in the osteoarthritic knee.9

and Plymouth, UK Survey of Health. The diagnosis of OA was defined by Using data from the community-based Somerset

4CTU Bern, Bern University

the presence of osteophytes in anteroposterior (AP) and Avon Survey of Health (SASH),15 16 we deter-

Hospital, Switzerland

5Department of Social Medicine, or lateral views. Bone attrition was graded from 0 (no mined whether bone attrition as detected on con-

University of Bristol, Bristol, UK attrition) to 3 (severe attrition >10 mm) and Kellgren ventional anteroposterior (AP) x-rays is associated

and Lawrence (K/L) scores were assigned on AP views. not only with knee pain but also with stiffness and

Correspondence to Logistic regression models adjusted for gender, age, disability.

Dr Stephan Reichenbach,

body mass index, effusion and K/L scores were used to

Institute of Social and

Preventive Medicine, University determine whether bone attrition was associated with METHODS

of Bern, Finkenhubelweg pain, stiffness and disability. Sampling of participants

11, 3012 Bern, Switzerland; Results Pain was reported in 84 knees (74%) with

rbach@ispm.unibe.ch

SASH is a population-based cross-sectional study

radiographic bone attrition compared with 505 (42%) of 28 080 people randomly selected from 40 general

without bone attrition (adjusted OR 2.22, 95% CI 1.29 to practices in the south-west of England.15 17 After

Accepted 11 August 2010 3.80). The adjusted OR was increased for day pain but

Published Online First exclusion of 2034 people who had either moved

24 September 2010

not for night pain (p for interaction <0.001). Stiffness out of the study area, suffered from a severe mental

was reported for 85 knees with bone attrition (75%) and or terminal illness or were deceased, 26 046 people

437 knees without (36%) (adjusted OR 3.23, 95% CI 1.85 were included in the study.

to 5.64). Disability was reported by 40 individuals with

bone attrition (50%) and 140 individuals without (24%)

(adjusted OR 2.09, 95% CI 1.19 to 3.68). Screening process

Conclusions Bone attrition detected on conventional All 26 046 subjects were sent a screening ques-

x-rays using a simple cheap technique is strongly tionnaire comprising questions on general health,

associated with the presence of day pain, stiffness and utilisation of health services and symptoms of

disability in knee OA. hip and knee disease. Non-respondents were sent

two reminders and contacted by telephone if

necessary.17 18 We screened people for knee pain

INTRODUCTION using a modified version of the question used in the

Knee pain is a major public health problem.1–3 In first National Health and Nutrition Examination

older people the cause of knee pain is generally Survey:19 ‘During the past 12 months, have you

attributed to osteoarthritis (OA).4 However, we had pain in or around either of your knees (hips)

know that many people with radiographic changes on most days for 1 month or longer?’ Participants

suggestive of knee OA are not in pain.5–7 In addition, who reported knee or hip pain were invited for fur-

knee pain can be due to a number of other patholo- ther examination either at a clinic or by home visit.

gies including periarticular problems such as anser- Examinations were organised into two phases by

ine bursitis8 and bone pathologies such as bone location of participating practices.

marrow lesions.9 Joint pathology has been assessed

radiographically in the past.10 However, because of Assessment of symptoms and signs

the relatively poor correlation between symptoms Examined participants were asked about knee pain,

and radiographic changes,5–7 most investigators stiffness and disability using the following ques-

now opt to use more sophisticated joint imaging tions: ‘In the past 12 months, have you had pain

techniques such as MRI.11 12 Alternatively, they in or around your left (right) knee on most days for

have looked for other technologies with which to 1 month or longer during the day?’ (yes/no). This

explore the problem, such as functional imaging of question was repeated for night pain, referring to

the brain.13 These techniques may provide us with ‘during the night’. Participants were considered to

valuable insights into pain mechanisms but cannot suffer from knee pain if they reported either day

easily be used in routine clinical work or in epide- or night pain. ‘In the past 12 months, have you

miological studies. experienced stiffness in or around your left (right)

Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:293–298. doi:10.1136/ard.2010.132985 293

Extended report

knee on most days for 1 month or longer (yes/no)?’ and ‘How radiographic knee OA9 with complete covariate information.

difficult is it for you to go outdoors and walk down the road To explore the impact of excluding knees or participants with

on your own (not difficult/quite difficult/very difficult/impos- missing covariate information, we calculated estimates of the

sible)?’ Disability was not assessed in the first 127 participants associations of bone attrition with symptoms separately for

who underwent clinical examination during the first phase of complete and incomplete datasets. In sensitivity analyses we

the study and considered present if participants indicated that distinguished between grade 1 and 2 bone attrition. p Values

walking was at least ‘quite difficult’. The presence of an effusion for interaction between estimated OR and extent of bone attri-

in either knee was determined based on clinical examination. tion were derived from the appropriate interaction term in the

logistic regression model. We then estimated separately the

Radiographic evaluation association of bone attrition with day pain and with night pain

Participants underwent weightbearing AP and lateral x-rays of using matched pairs logistic regression, which accounted for the

the knees according to a standardised protocol. For AP views correlation between the two pain types within knees. All analy-

the legs were extended in slight internal rotation. All films were ses were performed in STATA 10.1 (Stata Corporation, College

processed and assessed in a blinded manner. We used weight- Station, Texas, USA).

bearing AP knee x-rays that were considered to be normal to

develop templates of knee joint contour outlines.14 These could RESULTS

be overlaid onto the knee x-rays of the study subjects to deter- The flow of participants from screening stage to stage of clini-

mine the presence of bone attrition, defined as a vertical loss of cal examination was reported previously.15 16 In short, 22 978

bone volume in the affected condyle (figure 1). Alignment of individuals responded to the screening questionnaire, 22 217

the normal contours of the femur and tibia allowed measure- completed the question on hip pain and 22 379 the question

ment of the extent of bone attrition separately for the femo- on knee pain. A total of 6416 participants reported hip or knee

ral condyles and tibial plateaus. Three different template sizes pain (29%). Of these, 4304 were invited for further examination

were used for knees of small, medium or large dimensions. As (67%) and 2703 attended (63%).15 16 Figure 2 shows the flow

previously described, we graded attrition on a scale from 0 to 3 of clinic attendees through the study; 938 participants did not

(0 = no attrition, 1 = attrition of doubtful significance (<5 mm), have a radiographic examination, most frequently because they

2 = definite attrition of a moderate degree (5–10 mm), 3 = severe refused or because they felt unable to attend due to general frailty

attrition (>10 mm).14 Using a standard atlas,10 we then rated the or comorbid conditions. A total of 3530 knees from 1765 partici-

worst osteophytes from 0 to 3 (0 = none; 1 = minute; 2 = def- pants had undergone radiographic examination but 430 knees

inite, of a moderate degree; 3 = severe) for both parts of the were excluded, most frequently because radiographic examina-

tibiofemoral joint on AP and lateral x-rayss. OA was defined by tions performed before the beginning of the study could not be

the presence of grade 1 osteophytes or higher on AP or lateral obtained for central reading. Films of 3100 knees from 1571 par-

views.9 Finally, we assigned Kellgren/Lawrence (K/L) grades of ticipants were read and 1615 knees from 957 participants were

global radiological severity on AP views using a scale from 0 diagnosed with radiographic OA. Complete clinical data were

to 4 (0 = no features of OA, 1 = minute osteophytes of doubtful available for 1326 knees from 783 participants. Disability was

significance; 2 = definite osteophytes, no definite joint space not assessed for the first 127 participants with radiographic OA

narrowing; 3 = definite joint space narrowing of a moderate during the first phase, so data on disability was available for 656

degree; 4 = severe joint space impairment).20 One investigator participants with radiographic OA (figure 2).

(SR) who was blinded to each participant’s clinical information The characteristics of the 783 participants (1326 knees) with

performed a single assessment of all x-rays. A random sample of radiographic and clinical information are shown in table 1.

30 films was also assessed by one independent observer (PAD). Participants with bone attrition were on average 4 years older

Intrarater agreement was moderate for the semiquantitative than participants without bone attrition (p<0.001). The 114

grading of bone attrition with a weighted κ value of 0.82 (95% knees all had a K/L score ≥2, with a trend towards higher K/L

CI 0.61 to 1.00), was high for semiquantitative K/L grading with scores in knees with bone attrition as opposed to predominantly

a weighed κ value of 0.88 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.00) and was high low K/L scores in knees without (p<0.001). A total of 270 knees

for detection of osteophytes with a κ of 1.00 (95% CI 0.74 to without attrition were assigned a K/L score of 0, with osteo-

1.00). Inter-rater agreement was moderate for the semiquantita- phytes only detectable on lateral views. Effusions were detected

tive grading of bone attrition with a weighted κ value of 0.58 clinically in 77 knees overall (6%), and the percentages were

(95% CI 0.39 to 0.78), was moderate for semiquantitative K/L much the same in knees with and without bone attrition.

grading with a weighed κ value of 0.81 (95% CI 0.69 to 0.92) Pain was reported in 84 knees (74%) with radiographic bone

and was moderate for detection of osteophytes with a κ of 0.72 attrition compared with 505 knees (42%) without bone attri-

(95% CI 0.59 to 0.86). tion. Figure 3 shows crude and adjusted associations of bone

attrition with pain. In the crude analysis, the odds of pain were

Statistical analysis 3.92 times higher in knees with bone attrition compared with

Analyses were at knee level for the analysis of pain and stiffness knees without attrition (95% CI 2.37 to 6.48). After adjustment

and at participant level for disability. Logistic regression mod- for age, gender, body mass index, K/L score and the presence of

els were used based on robust standard errors that accounted joint effusion, the OR was 2.22 (95% CI 1.29 to 3.80). Figure 4

for the clustering of knees within participants where appropri- shows associations separately for knees with small and moder-

ate and the association of bone attrition grade ≥1 (pre-speci- ate bone attrition compared with knees without bone attrition.

fied) with knee pain, stiffness and disability was determined. Crude and adjusted ORs were similar, CIs wide and tests for

We estimated crude OR with corresponding 95% CIs and OR interaction between estimated OR and extent of bone attrition

adjusted for gender, age, body mass index and overall radio- negative. Figure 5 shows separate estimates of the association of

graphic severity based on K/L scores and the presence of joint bone attrition with day pain and with night pain. In crude and

effusion. Analyses were restricted to knees or participants with adjusted analyses, ORs were more pronounced for day pain but

294 Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:293–298. doi:10.1136/ard.2010.132985

Extended report

not for night pain, with positive tests for interaction between Attendees were more likely than non-attendees to report pain

estimated OR and type of pain. In the adjusted analysis the OR (71% vs 29%), stiffness (68% vs 32%) and disability (58% vs

was increased for day pain (OR 2.37, 95% CI 1.48 to 3.80) but 42%). A total of 1765 attendees with 3530 knees underwent

not for night pain (OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.53). radiographic examination (65%) and films of 3100 knees were

Stiffness was reported for 85 knees with bone attrition (75%) read (88%). Those with knee films available were more likely

and 437 knees without (36%). The OR for the association of than those without films to report pain (88% vs 12%), stiffness

bone attrition with stiffness was 5.20 in the crude analysis (95% (89% vs 11%) and disability (79% vs 21%). Among participants

CI 3.09 to 8.75) and 3.23 after adjustment (95% CI 1.85 to 5.64, with knee films, those with complete clinical data were again

figure 3). ORs of stiffness were similar for knees with small bone

attrition and those with moderate bone attrition, CIs wide and A

tests for interaction between estimated OR and extent of bone Clinically examined:

attrition negative (figure 4). Disability was assessed at the par- 2703 participants (5406 knees)

ticipant level and reported by 40 individuals with bone attrition C

(50%) and 140 individuals without (24%). The OR for the asso- No radiographic examination: 938 participants

ciation of bone attrition with disability was 3.11 in the crude Refused: 450 participants

analysis (95% CI 1.93 to 5.02) and 2.09 after adjustment (95% Unable to attend: 223 participants

Logistic reasons: 120 participants

CI 1.19 to 3.68, figure 3). ORs of disability were similar for knees Reason unclear: 145 participants

with small bone attrition and those with moderate bone attri-

tion, CIs wide and tests for interaction between estimated OR

and extent of bone attrition negative (figure 4). Had radiographic examination

1765 participants (3530 knees)

A C Excluded: 430 knees

Films requested, not received: 377 knees

Knee implant: 48 knees

Technical difficulties: five knees

B

Radiographs read

1571 participants (3100 knees)

No knee osteoarthritis: 1485 knees

B

Radiographs with knee osteoarthritis

957 participants (1615 knees)

Incomplete clinical data: 289 knees

Complete clinical data available

Pain: 783 participants (1326 knees)

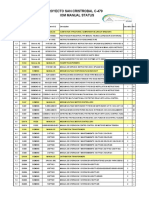

Figure 1 Different grades of bone attrition. (A) Grade 1 bone attrition Stiffness: 783 participants (1326 knees)

Disability: 656 participants§§

(white arrow) of <5 mm of the medial tibia plateau. (B) Grade 2 bone

attrition (white arrow) of 5–10 mm of the lateral tibia plateau. (C) Grade Figure 2 Study flowchart. Note that disability was not assessed in

3 bone attrition of >10 mm of the lateral tibia with the overlaid template the first 127 participants of the first phase of the study, so only 656

to outline the joint contour. Broken lines on the template indicate the participants contributed to the analysis of disability.

cut-off points for levels of bone loss. Modified from Dieppe et al14.

Table 1 Characteristics of participants

Presence of bone attrition

Yes No p Value

Participant-level data n=80 n=576

Age (years) 79.5 (10.3) 75.3 (9.6) <0.001

Men 38 (48%) 228 (40%) 0.19

BMI (kg/m2) 28.3 (4.3) 28.3 (4.7) 0.60

Knee-level data n=114 n=1212

Kellgren-Lawrence score <0.001

0 0 (0%) 270 (22%)

1 0 (0%) 222 (18%)

2 15 (13%) 519 (43%)

3 40 (35%) 179 (15%)

4 59 (52%) 22 (2%)

Effusion 8 (7%) 69 (6%) 0.63

BMI, body mass index.

Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:293–298. doi:10.1136/ard.2010.132985 295

Extended report

(A) Crude analyses A) Crude P<0.001

Knee pain 3.92 (2.37 to 6.48) Day pain 4.01 (2.61 to 6.19)

Night pain 1.64 (1.05 to 2.55)

Stiffness 5.20 (3.09 to 8.75)

B) Adjusted* P<0.001

Disability 3.11 (1.93 to 5.02) Day pain 2.37 (1.48 to 3.80)

(B) Adjusted analyses* Night pain 0.94 (0.58 to 1.53)

Knee pain 2.22 (1.29 to 3.80)

Stiffness 3.23 (1.85 to 5.64) 0.125 0.25 0.5 1.0 2.0 4.0 8.0 OR

Disability 2.09 (1.19 to 3.68) Figure 5 Associations of bone attrition with day pain and night pain

0.125 0.25 0.5 1.0 2.0 4.0 8.0 OR

separately. *Analyses were adjusted for gender, age, body mass index,

Kellgren-Lawrence score and presence of joint effusion.

Figure 3 Association between presence of bone attrition and knee

pain, stiffness and disability. Analyses of knee pain and stiffness were at the time at which the x-rays were obtained and we could

performed in 1326 knees and analyses of disability in 656 participants. not determine the association between bone attrition and pain

*Analyses were adjusted for gender, age, body mass index, Kellgren- intensity. Third, our analysis is based on individuals experienc-

Lawrence score and presence of joint effusion. ing hip or knee pain in the community and cannot necessarily

be generalised to other settings. Finally, participants in the study

Knee pain P=0.86 did not undergo MRI examination so we were unable to account

for other pathologies including meniscal damage, bone marrow

Small 2.33 (1.31 to 4.13)

lesions or bursitis. Since subchondral bone marrow lesions are

associated with bone attrition in MRI,21 the observed associa-

Moderate 2.09 (0.70 to 6.26)

tion of bone attrition with pain might be partially confounded

by bone marrow lesions undetected on conventional x-rays.

Stiffness P=0.52

The range of causes for knee pain in adults is large, ranging

Small 3.58 (1.95 to 6.57) from local problems such as trauma and arthritis to referred

pain from the hip or central pain sensitisation problems.22 The

Moderate 2.42 (0.86 to 6.79) usual diagnosis established as a cause for knee pain in those

aged ≥45 years in daily practice is OA,23 which is unsurprising in

Disability P=0.42

view of the high prevalence of patients with clinical and radio-

graphic signs of OA.24 However, the association of bone attri-

Small 3.25 (1.55 to 6.78) tion as assessed on conventional x-rays has only been partially

explored, and its association with stiffness and self-reported dis-

Moderate 1.79 (0.52 to 6.14) ability has never been addressed to our knowledge. Despite the

advent of MRI studies in patients with knee OA to investigate

0.125 0.25 0.5 1.0 2.0 4.0 8.0 OR bone pathologies,9 25 26 it is too expensive for routine use and

is unlikely to become part of clinical practice in patients with

Figure 4 Associations of bone attrition with knee pain according to

extent of bone attrition. All analyses were adjusted for gender, age, body OA in many healthcare settings other than cases of suspected

mass index, Kellgren-Lawrence score and presence of joint effusion. meniscal tears. Our study contributes to widening the focus

Only one knee with severe bone attrition was included in the study and when interpreting conventional x-rays from exclusive attention

therefore associations in knees with severe bone attrition could not be to joint space narrowing and osteophytes to a more integrated

estimated. view which also involves subchondral bone. The approach of

using conventional AP x-rays to detect bone attrition14 is cheap,

more likely than those without films to report pain (80% vs simple and applicable to population-based research and clinical

20%), stiffness (81% vs 19%) and disability (78% vs 22%). practice.

Pioneering work on the association between bone patholo-

DISCUSSION gies and pain was undertaken by Arnoldi et al27 28 in the 1970s

This analysis of adults aged ≥35 years shows that the presence and 1980s using intraosseous pressure measurement and other

of bone attrition found on plain x-rays is associated with 2–3- techniques. In the 1990s, bone scintigraphy was used to deter-

fold increased odds of pain, stiffness and disability. In both crude mine whether subchondral bone activity was related to both

and adjusted analyses the associations were pronounced for day pain and progression of OA,29–31 providing an impetus to bone

pain but not for night pain. When the associations were deter- research in OA. In the last decade, MRI studies tell a similar

mined separately for grades 1 and 2 bone attrition we found story with associations found between bone marrow lesions or

similar increases in the odds of pain, with widely overlapping bone attrition and knee pain.9 26 32 33 Distinguishing between

CIs and negative tests for interaction between extent of attrition day and night pain, Hernández-Molina et al32 found an asso-

and association with knee pain. ciation of bone attrition with day pain but not night pain. In

The strengths of the study include the large number of people agreement with Hernández-Molina et al32 but contrary to our

involved, the population-based recruitment of study participants, earlier suggestion that bone attrition could be associated with

their transparent pathway to clinical and radiographic exami- night pain,14 we found a strong association of bone attrition

nation15 and the fact that the x-rays were assessed by a single with day pain but none with night pain in the adjusted analysis.

observer. However, there are four major limitations to the study. Taken together, a variety of techniques has been used during the

First, it is purely cross-sectional, which implicitly prevents us last 40 years to explore the association between bone patholo-

from drawing any conclusions about the causality of observed gies and pain but, to our knowledge, this is the first study to

associations. Second, pain was only assessed as present or absent use conventional x-rays for assessing bone attrition in a large

296 Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:293–298. doi:10.1136/ard.2010.132985

Extended report

population-based sample and to determine the association of paper and all authors contributed to the final draft. PJ and PAD are the guarantors of

bone attrition, not only with pain but also with stiffness and the study.

disability. These three measures of disease severity are likely to Ethics approval This study was conducted with the approval of the local research

be interrelated, and both pain and stiffness may be on the causal ethics committees of Somerset and Avon and all participants provided written

informed consent.

pathway between bone attrition and disability. This could be

partially addressed by including either of the two measures as Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

independent variables in the logistic regression model. In our

study the crude OR for the association between bone attrition REFERENCES

and disability of 3.11 (95% CI 1.93 to 5.02) became somewhat 1. Webb R, Brammah T, Lunt M, et al. Opportunities for prevention of ‘clinically sig-

less pronounced after adjusting for knee pain (OR 2.75, 95% CI nificant’ knee pain: results from a population-based cross sectional survey. J Public

1.69 to 4.47) and stiffness (OR 2.45, 95% CI 1.50 to 4.02). Health (Oxf) 2004;26:277–84.

2. Buckwalter JA, Saltzman C, Brown T. The impact of osteoarthritis: implications for

MRI studies suggest that many knees with mild radiographic research. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004;427:S6–15.

OA without joint space narrowing have some evidence of bone 3. van der Waal JM, Bot SD, Terwee CB, et al. Course and prognosis of knee com-

attrition.33 Several interrelated observations deserve further plaints in general practice. Arthritis Rheum 2005;53:920–30.

attention. First, malalignment of the knee was found to be asso- 4. Dieppe PA, Lohmander LS. Pathogenesis and management of pain in osteoarthritis.

Lancet 2005;365:965–73.

ciated with the prevalence and incidence of subchondral bone 5. Hochberg MC, Lawrence RC, Everett DF, et al. Epidemiologic associations of pain in

attrition in a compartment-specific manner.34 Second, bone mar- osteoarthritis of the knee: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination

row lesions were associated with and predictive for subchon- Survey and the National Health and Nutrition Examination-I Epidemiologic Follow-up

dral bone attrition.21 26 Third, subchondral bone attrition was Survey. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1989;18:4–9.

strongly associated with cartilage loss within the same subre- 6. Cicuttini FM, Baker J, Hart DJ, et al. Association of pain with radiological

changes in different compartments and views of the knee joint. Osteoarthr Cartil

gion of the knee.35 Taken together, this may suggest a sequen- 1996;4:143–7.

tial process with overload due to malalignment causing bone 7. Hannan MT, Felson DT, Pincus T. Analysis of the discordance between radiographic

marrow lesions first which, in turn, lead to weakening of the changes and knee pain in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol 2000;27:1513–17.

subchondral osseous plate and eventual bone attrition and sub- 8. Rennie WJ, Saifuddin A. Pes anserine bursitis: incidence in symptomatic knees and

clinical presentation. Skeletal Radiol 2005;34:395–8.

sequent damage of the cartilage. 9. Felson DT, Chaisson CE, Hill CL, et al. The association of bone marrow lesions with

There are implications of our findings, both for research and pain in knee osteoarthritis. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:541–9.

clinical practice. The data suggest that we need to investigate 10. Altman RD, Hochberg M, Murphy WA, Jr, et al. Atlas of individual radiographic

subchondral bone changes as well as articular cartilage when features in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil 1995;3:3–70.

studying the pathogenesis of both joint damage and pain in OA. 11. Wluka AE, Ding C, Jones G, et al. The clinical correlates of articular cartilage defects

in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: a prospective study. Rheumatology (Oxford)

Bone loss of the sort detected by our method implies serious 2005;44:1311–16.

damage to subchondral bone; this may be a critical feature in 12. Peterfy CG, Guermazi A, Zaim S, et al. Whole-Organ Magnetic Resonance Imaging

the sequential disease process and it may be more important Score (WORMS) of the knee in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil 2004;12:177–90.

to focus on the subchondral bone rather then the joint cartilage 13. Kulkarni B, Bentley DE, Elliott R, et al. Arthritic pain is processed in brain areas

concerned with emotions and fear. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:1345–54.

when developing novel potentially disease-modifying drugs for 14. Dieppe PA, Reichenbach S, Williams S, et al. Assessing bone loss on radiographs of

OA. the knee in osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:3536–41.

In conclusion, we found bone attrition detected on conven- 15. Frankel S, Eachus J, Pearson N, et al. Population requirement for primary hip-

tional AP x-rays using a simple and cheap technique14 associated replacement surgery: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 1999;353:1304–9.

with the presence of day pain, stiffness and disability in partici- 16. Jüni P, Dieppe P, Donovan J, et al. Population requirement for primary

knee replacement surgery: a cross-sectional study. Rheumatology (Oxford)

pants of a population-based study of individuals with knee OA. 2003;42:516–21.

17. Eachus J, Williams M, Chan P, et al. Deprivation and cause specific morbidity:

Acknowledgements The authors thank all study participants and the partners evidence from the Somerset and Avon survey of health. BMJ 1996;312:287–92.

and staff of participating general practices for their support and interest in the study. 18. Jüni P, Low N, Reichenbach S, et al. Gender inequity in the provision of care for hip

The authors are indebted to the whole of the Somerset and Avon Survey of Health disease: population-based cross-sectional study. Osteoarthr Cartil 2010;18:640–5.

research team: Kirsty Alchin, Ros Berkeley-Hill, Jane Brooks, Hilary Brownett, Phil 19. Anderson JJ, Felson DT. Factors associated with osteoarthritis of the knee in the

Chan, Clare Cross, Catherine Dawe, Cathy Doel, Jenny Eachus, Helen Forward, first national Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (HANES I). Evidence for an

Matthew Grainge, Fiona Hollyman, Sue Jones, Helen Moore, Kate Morris, Nicky association with overweight, race, and physical demands of work. Am J Epidemiol

Pearson, Brian Quilty, Chris Smith, Lynne Smith, Gwyn Williams, Mark Williams and 1988;128:179–89.

Andrea Wilson; and Allan Douglas and Doreen Cook at Dillon Computing. Finally, we 20. Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum

are grateful to our co-investigators, Jenny Donovan, Tim Peters and Stephen Frankel. Dis 1957;16:494–502.

The Department of Social Medicine is the lead centre for the MRC Health Services 21. Roemer FW, Neogi T, Nevitt MC, et al. Subchondral bone marrow lesions are highly

Research Collaboration. The authors are grateful to Pete Shiarly for the management associated with, and predict subchondral bone attrition longitudinally: the MOST

and maintenance of the database. study. Osteoarthr Cartil 2010;18:47–53.

22. Kidd BL, Photiou A, Inglis JJ. The role of inflammatory mediators on nociception and

Funding The Somerset and Avon Survey of Health was originally funded by the pain in arthritis. Novartis Found Symp 2004;260:122–33; discussion 133–8, 277–9.

Department of Health and the South and West NHS Research and Development 23. Altman RD. Criteria for classification of clinical osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol Suppl

Directorate. This work was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grants 1991;27:10–12.

nos 3233-066377 and 3200-066378) and by the British Arthritis Research Campaign. 24. Jüni P, Reichenbach S, Dieppe P. Osteoarthritis: rational approach to treating the

The funding bodies had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, individual. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2006;20:721–40.

management, analysis or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review or approval 25. Wluka AE, Wolfe R, Stuckey S, et al. How does tibial cartilage volume relate to

of the manuscript. SR is the recipient of a Research Fellowship from the Swiss symptoms in subjects with knee osteoarthritis? Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:264–8.

National Science Foundation (grant number PBBEB-115067) and of an educational 26. Torres L, Dunlop DD, Peterfy C, et al. The relationship between specific tissue

grant from the Swiss Society of Rheumatology. lesions and pain severity in persons with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil

2006;14:1033–40.

Competing interests None. 27. Arnoldi CC, Lemperg K, Linderholm H. Intraosseous hypertension and pain in the

Contributors PJ and PAD conceived the study and were primarily responsible for knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1975;57:360–3.

protocol development. SR, PJ, SW and PAD contributed to data collection. EN, SR 28. Arnoldi CC, Djurhuus JC, Heerfordt J, et al. Intraosseous phlebography, intraosseous

and PJ performed the data preparation and analysis. All authors reviewed the protocol pressure measurements and 99mTC-polyphosphate scintigraphy in patients with

and participated in data interpretation. SR, PJ and PAD wrote the first draft of the various painful conditions in the hip and knee. Acta Orthop Scand 1980;51:19–28.

Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:293–298. doi:10.1136/ard.2010.132985 297

Extended report

29. Dieppe P, Cushnaghan J, Young P, et al. Prediction of the progression of joint space narrowing 33. Reichenbach S, Guermazi A, Niu J, et al. Prevalence of bone attrition on

in osteoarthritis of the knee by bone scintigraphy. Ann Rheum Dis 1993;52:557–63. knee radiographs and MRI in a community-based cohort. Osteoarthr Cartil

30. McCrae F, Shouls J, Dieppe P, et al. Scintigraphic assessment of osteoarthritis of the 2008;16:1005–10.

knee joint. Ann Rheum Dis 1992;51:938–42. 34. Neogi T, Nevitt M, Niu J, et al. Subchondral bone attrition may be a reflection

31. Hutton CW, Higgs ER, Jackson PC, et al. 99mTc HMDP bone scanning in generalised of compartment-specific mechanical load: the MOST Study. Ann Rheum Dis

nodal osteoarthritis. II. The four hour bone scan image predicts radiographic change. 2010;69:841–4.

Ann Rheum Dis 1986;45:622–6. 35. Neogi T, Felson D, Niu J, et al. Cartilage loss occurs in the same subregions as

32. Hernández-Molina G, Neogi T, Hunter DJ, et al. The association of bone attrition with subchondral bone attrition: a within-knee subregion-matched approach from the

knee pain and other MRI features of osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:43–7. Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1539–44.

298 Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:293–298. doi:10.1136/ard.2010.132985

You might also like

- Nice 1stDocument6 pagesNice 1staldiNo ratings yet

- Good Reliability Questionable Validity O20170518 3475 Qhxhhe With Cover Page v2Document183 pagesGood Reliability Questionable Validity O20170518 3475 Qhxhhe With Cover Page v2Ary MfNo ratings yet

- A Naturally Aging Knee or Development of Early KN - 2018 - Osteoarthritis and CDocument6 pagesA Naturally Aging Knee or Development of Early KN - 2018 - Osteoarthritis and CVanessa MartinsNo ratings yet

- So Sang Sieu Am Va MriDocument12 pagesSo Sang Sieu Am Va Mrithu hangNo ratings yet

- Use of Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation Device in Early Osteoarthritis of The KneeDocument7 pagesUse of Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation Device in Early Osteoarthritis of The KneeAlifah Nisrina Rihadatul AisyNo ratings yet

- Osteoarthritis of The Hip: Clinical PracticeDocument9 pagesOsteoarthritis of The Hip: Clinical PracticeMarina Tomasenco - DaniciNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Muscle Activation and Knee Mechanics During Gait Between Patients With Non-Traumatic and Post-Traumatic Knee OsteoarthritisDocument10 pagesA Comparison of Muscle Activation and Knee Mechanics During Gait Between Patients With Non-Traumatic and Post-Traumatic Knee OsteoarthritisSiriratNo ratings yet

- Journal EadiologiDocument5 pagesJournal EadiologiAhmad IsmatullahNo ratings yet

- 1756-185X.13082) Huang, Lanfeng Guo, Bin Xu, Feixiang Zhao, Jinsong - Effects of Quadriceps Functional Exercise With IsDocument8 pages1756-185X.13082) Huang, Lanfeng Guo, Bin Xu, Feixiang Zhao, Jinsong - Effects of Quadriceps Functional Exercise With IsTrisna ArinataNo ratings yet

- Pain and Effusion and Quadriceps Activation and StrengthDocument6 pagesPain and Effusion and Quadriceps Activation and StrengthЯнь НгуенNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Remato 2Document8 pagesJurnal Remato 2aandakuNo ratings yet

- Dolor Sacro IliacoDocument6 pagesDolor Sacro Iliacomaria antonieta0102No ratings yet

- 10b. Diagnosis Journal Review 2 - Hip Pain Osteoarthritis BMJDocument8 pages10b. Diagnosis Journal Review 2 - Hip Pain Osteoarthritis BMJPPDSNeurologiAgustus 2021No ratings yet

- Paper 4 CAIDocument6 pagesPaper 4 CAIhareem7bilalNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0003999319303892 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0003999319303892 MainRizkyrafiqoh afdinNo ratings yet

- Deepti - 2016 Effects of Retrowalking On Osteoarthritis of Knee in GeriatricDocument7 pagesDeepti - 2016 Effects of Retrowalking On Osteoarthritis of Knee in Geriatricnur pratiwiNo ratings yet

- Management of Knee OsteoarthritisDocument35 pagesManagement of Knee OsteoarthritisChukwuemeka ChidogoNo ratings yet

- Tatalaksana OsteonekrosisDocument78 pagesTatalaksana OsteonekrosisRama MahendraNo ratings yet

- Tennis Elbow JOSPT ArticleDocument11 pagesTennis Elbow JOSPT ArticleHasan RahmanNo ratings yet

- Accuracy of Physical Examination in Subacromial Impingement SyndromeDocument5 pagesAccuracy of Physical Examination in Subacromial Impingement SyndromeClaudia BuitragoNo ratings yet

- 595 Full PDFDocument7 pages595 Full PDFI Nengah Dwi DarmawanNo ratings yet

- PIIS1063458419312099Document6 pagesPIIS1063458419312099rahmarahmatNo ratings yet

- Is The Prognosis of Osgood-Schlatter Poorer Than Anticipated?Document9 pagesIs The Prognosis of Osgood-Schlatter Poorer Than Anticipated?gastón giosciaNo ratings yet

- Genicular Nerve Ablation Zeitlinger2019Document7 pagesGenicular Nerve Ablation Zeitlinger2019drjorgewtorresNo ratings yet

- Effect of Foot Strengthening Exercises in Osteoarthritis KneeDocument5 pagesEffect of Foot Strengthening Exercises in Osteoarthritis KneefiaNo ratings yet

- Brazilian Journal of Physical TherapyDocument8 pagesBrazilian Journal of Physical TherapyLina M GarciaNo ratings yet

- Chronic Knee Pain Is The Paramount Presentation in Patients With Nail Patella SyndromeDocument7 pagesChronic Knee Pain Is The Paramount Presentation in Patients With Nail Patella SyndromeAthenaeum Scientific PublishersNo ratings yet

- Research: Lateral Wedge Insoles For Medial Knee Osteoarthritis: 12 Month Randomised Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesResearch: Lateral Wedge Insoles For Medial Knee Osteoarthritis: 12 Month Randomised Controlled TrialGheavita Chandra DewiNo ratings yet

- The Role of Muscle Strength & Activation Patterns in Patellofemoral PainDocument5 pagesThe Role of Muscle Strength & Activation Patterns in Patellofemoral Paincristian fabian perez romeroNo ratings yet

- Nihms 1002530Document15 pagesNihms 1002530Instalasi Rehabilitasi MedikNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Patellar Tendinopathy Using The Single Leg Decline Squat Test Is Pain Location Important IMPORTANTEDocument6 pagesEvaluation of Patellar Tendinopathy Using The Single Leg Decline Squat Test Is Pain Location Important IMPORTANTERonny Araya AbarcaNo ratings yet

- Tare de TotDocument25 pagesTare de TotantohebogdanalexNo ratings yet

- Physiotherapy Management of Hip OsteoarthritisDocument14 pagesPhysiotherapy Management of Hip Osteoarthritisaraaela 25No ratings yet

- Balneo 305Document6 pagesBalneo 305Nicoleta TudorachiNo ratings yet

- 2Document6 pages2Rashmi GodeshwerNo ratings yet

- Journal of Rehabilitation Sciences and Research: Journal Home Page: JRSR - Sums.ac - IrDocument6 pagesJournal of Rehabilitation Sciences and Research: Journal Home Page: JRSR - Sums.ac - IrAtika MayadahNo ratings yet

- Movement Detection Impaired in Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis Compared To Healthy Controls: A Cross-Sectional Case-Control StudyDocument10 pagesMovement Detection Impaired in Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis Compared To Healthy Controls: A Cross-Sectional Case-Control StudyDavid SugiartoNo ratings yet

- Babaei Ghazani2018Document11 pagesBabaei Ghazani2018Renato BastosNo ratings yet

- Hochberg 2004Document4 pagesHochberg 2004MARIA ISABELA URREA CARDONANo ratings yet

- Single Leg Decline Squat y Tendinopatia PatelarDocument25 pagesSingle Leg Decline Squat y Tendinopatia PatelarAYMARA GABRIELA MORENO SANCHEZNo ratings yet

- Sciatica and The Sacroiliac JointDocument4 pagesSciatica and The Sacroiliac JointfilipecorsairNo ratings yet

- Cadera 01Document6 pagesCadera 01Jordi ArlandisNo ratings yet

- Topp 2002Document9 pagesTopp 2002Muhamad BenyaminNo ratings yet

- 53 - Changes in Arthroscopic Findings in The Anterior Cruciate Ligament Deficient Knee Prior To Reconstructive SurgeryDocument3 pages53 - Changes in Arthroscopic Findings in The Anterior Cruciate Ligament Deficient Knee Prior To Reconstructive SurgeryrandocalNo ratings yet

- Overuse Ankle Injuries in Professional Irish DancersDocument5 pagesOveruse Ankle Injuries in Professional Irish DancersPookcey IdsariyaNo ratings yet

- Melese 2020 - Effectiveness of Kinesiotaping OA Knee SRMA jpr-13-1267Document10 pagesMelese 2020 - Effectiveness of Kinesiotaping OA Knee SRMA jpr-13-1267Ikhsan JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Kotnis Et Al. - Hip Arthrography in The Assessment of Children WitDocument6 pagesKotnis Et Al. - Hip Arthrography in The Assessment of Children WitsalvadorNo ratings yet

- Observational Study of Incidence of Rotator Cuff Tear in Patients With Shoulder Pain and StiffnessDocument8 pagesObservational Study of Incidence of Rotator Cuff Tear in Patients With Shoulder Pain and StiffnessAthenaeum Scientific PublishersNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S101595842100292X MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S101595842100292X MainNUR HAMIDAHNo ratings yet

- Pereira 2015Document9 pagesPereira 2015Amalia RosaNo ratings yet

- Journal Pre-Proof: ExploreDocument43 pagesJournal Pre-Proof: ExploreLuís CorreiaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal r4Document9 pagesJurnal r4Rezkina Azizah PutriNo ratings yet

- Associations of Radiological Osteoarthritis of The Hip and Knee With Locomotor Disability in The Rotterdam StudyDocument6 pagesAssociations of Radiological Osteoarthritis of The Hip and Knee With Locomotor Disability in The Rotterdam StudyRebecca CooperNo ratings yet

- Does Osteoporosis Increase Early Subsidence of Cementless Double-Tapered Femoral Stem in Hip Arthroplasty?Document5 pagesDoes Osteoporosis Increase Early Subsidence of Cementless Double-Tapered Femoral Stem in Hip Arthroplasty?LuisAngelPonceTorresNo ratings yet

- Rooij Et Al-2016-Arthritis Care & ResearchDocument12 pagesRooij Et Al-2016-Arthritis Care & ResearchJennifer JaneNo ratings yet

- Ankle Stabilization With Arthroscopic Versus Open With Suture Tape Augmentation Techniques X1D XJ. George DeVries PDFDocument5 pagesAnkle Stabilization With Arthroscopic Versus Open With Suture Tape Augmentation Techniques X1D XJ. George DeVries PDFcrpcsxfdkgNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 1Document8 pagesJurnal 1Andre PratamaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Static Knee Joint Flexion On Vastus Medialis Obliquus Fiber Angle in Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome - An Ultrasonographic StudyDocument9 pagesEffect of Static Knee Joint Flexion On Vastus Medialis Obliquus Fiber Angle in Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome - An Ultrasonographic Studycris weeNo ratings yet

- Choi 2012Document7 pagesChoi 2012bbiibibibibibibibibiNo ratings yet

- Use of Natural Zeolite Clinoptilolite in AgricultuDocument8 pagesUse of Natural Zeolite Clinoptilolite in AgricultuMiranti AlfainiNo ratings yet

- Public Versus Private Education - A Comparative Case Study of A P PDFDocument275 pagesPublic Versus Private Education - A Comparative Case Study of A P PDFCindy DiotayNo ratings yet

- CHP 11: Setting Goals and Managing The Sales Force's PerformanceDocument2 pagesCHP 11: Setting Goals and Managing The Sales Force's PerformanceHEM BANSALNo ratings yet

- 47 Vocabulary Worksheets, Answers at End - Higher GradesDocument51 pages47 Vocabulary Worksheets, Answers at End - Higher GradesAya Osman 7KNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument2 pagesUntitledRoger GutierrezNo ratings yet

- The Normal Distribution and Sampling Distributions: PSYC 545Document38 pagesThe Normal Distribution and Sampling Distributions: PSYC 545Bogdan TanasoiuNo ratings yet

- DIN EN 12516-2: January 2015Document103 pagesDIN EN 12516-2: January 2015ReytingNo ratings yet

- Burton 1998 Eco Neighbourhoods A Review of ProjectsDocument20 pagesBurton 1998 Eco Neighbourhoods A Review of ProjectsAthenaMorNo ratings yet

- Architect Magazine 2023 0506Document152 pagesArchitect Magazine 2023 0506fohonixNo ratings yet

- Case Study GingerDocument2 pagesCase Study Gingersohagdas0% (1)

- Promises From The BibleDocument16 pagesPromises From The BiblePaul Barksdale100% (1)

- Hotel BookingDocument1 pageHotel BookingJagjeet SinghNo ratings yet

- Strength Exp 2 Brinell Hardness TestDocument13 pagesStrength Exp 2 Brinell Hardness Testhayder alaliNo ratings yet

- 11 PJBUMI Digital Data Specialist DR NOOR AZLIZADocument7 pages11 PJBUMI Digital Data Specialist DR NOOR AZLIZAApexs GroupNo ratings yet

- McEwan Pacific Student Scholarship 1374 RegulationsDocument2 pagesMcEwan Pacific Student Scholarship 1374 RegulationsHaitelenisia Hei'ululua KAMANo ratings yet

- Coaching Manual RTC 8Document1 pageCoaching Manual RTC 8You fitNo ratings yet

- Jane AustenDocument2 pagesJane Austendfaghdfo;ghdgNo ratings yet

- The Role of Religion in The Causation of Global Conflict & Peace and Other Related Issues Regarding Conflict ResolutionDocument11 pagesThe Role of Religion in The Causation of Global Conflict & Peace and Other Related Issues Regarding Conflict ResolutionlorenNo ratings yet

- Basic Elements of Rural DevelopmentDocument7 pagesBasic Elements of Rural DevelopmentShivam KumarNo ratings yet

- Degree Program Cheongju UniversityDocument10 pagesDegree Program Cheongju University심AvanNo ratings yet

- Ag Advace Check 8-30Document1 pageAg Advace Check 8-30AceNo ratings yet

- 413 14 Speakout Upper Intermediate 2nd Tests With Key and ScriptDocument158 pages413 14 Speakout Upper Intermediate 2nd Tests With Key and ScriptHal100% (2)

- Arthropods: Surviving The Frost: Charmayne Roanna L. GalangDocument2 pagesArthropods: Surviving The Frost: Charmayne Roanna L. GalangBabes-Rose GalangNo ratings yet

- NR Serial Surname Given Name Middlename: Republic of The Philippines National Police CommissionDocument49 pagesNR Serial Surname Given Name Middlename: Republic of The Philippines National Police CommissionKent GallardoNo ratings yet

- Summer Anniversary: by Chas AdlardDocument3 pagesSummer Anniversary: by Chas AdlardAntonette LavisoresNo ratings yet

- Proyecto San Cristrobal C-479 Iom Manual StatusDocument18 pagesProyecto San Cristrobal C-479 Iom Manual StatusAllen Marcelo Ballesteros LópezNo ratings yet

- Global Slump: The Economics and Politics of Crisis and Resistance by David McNally 2011Document249 pagesGlobal Slump: The Economics and Politics of Crisis and Resistance by David McNally 2011Demokratize100% (5)

- Romeuf Et Al., 1995Document18 pagesRomeuf Et Al., 1995David Montaño CoronelNo ratings yet

- Back WagesDocument24 pagesBack WagesfaisalfarizNo ratings yet

- State Public Defender's Office InvestigationDocument349 pagesState Public Defender's Office InvestigationwhohdNo ratings yet

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (42)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (24)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (80)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Summary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Sleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningFrom EverandSleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (328)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeFrom EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (253)

- Gut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerFrom EverandGut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (392)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (169)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- To Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceFrom EverandTo Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (51)

- An Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyFrom EverandAn Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- 12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosFrom Everand12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (207)