Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Coronavirus Pandemic A Possible Mode

Uploaded by

walkensiocsOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Coronavirus Pandemic A Possible Mode

Uploaded by

walkensiocsCopyright:

Available Formats

Nature and Science of Sleep Dovepress

open access to scientific and medical research

Open Access Full Text Article

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The Coronavirus Pandemic: A Possible Model of

the Direct and Indirect Impact of the Pandemic on

Sleep Quality in Italians

Nature and Science of Sleep downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 54.147.179.18 on 05-Nov-2021

This article was published in the following Dove Press journal:

Nature and Science of Sleep

Maria Casagrande 1 Purpose: This study aimed to assess the direct and indirect impact of COVID-19-related

Giuseppe Forte 2 aspects on self-reported sleep quality, considering the moderator role of some psychological

Renata Tambelli 1 variables.

Francesca Favieri 2 Methods: During the first weeks of the lockdown in Italy, 2286 respondents (1706 females

and 580 males; age range: 18–74 years) completed an online survey that collected socio-

For personal use only.

1

Dipartimento di Psicologia Dinamica,

demographic information and data related to the experience with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Clinica e Salute, “Sapienza” Università di

Roma, Rome, Italy; 2Dipartimento di Some questionnaires assessed sleep quality, psychological well-being, general psychopathol-

Psicologia, “Sapienza” Università di ogy, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders symptoms, and anxiety. The path analysis was adopted.

Roma, Rome, Italy

Results: The study confirms a direct effect of some aspects ascribable to the pandemic, with

a mediator role of the psychological variables. Lower sleep quality was directly related to the

days spent at home in confinement and the knowledge of people affected by the COVID-19.

All the other aspects related to the COVID-19 pandemic influenced sleep quality through the

mediator effect of psychological variables.

Conclusion: This study highlighted that the psychological condition of the population has

been influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic and the government actions taken to contain it,

but it has also played an important role in mediating the quality of sleep, creating a vicious

circle on people’s health. The results suggest that a health emergency must be accompanied

by adequate social support programs to mitigate the fear of infection and promote adequate

resilience to accept confinement and social distancing. Such measures would moderate

psychological distress and improve sleep quality.

Keywords: COVID-19, pandemic, sleep quality, psychological distress, home confinement,

social isolation

Introduction

The Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic severely impacted the world-

wide population, involving aspects closely related to physical health, political,

social, economic, and psychological conditions.1–3 Italy was one of the first and

most affected countries. The rapid spread of the virus led the Italian government to

implement exceptional containment measures of social distancing, including social

isolation and home confinement, between March and May 2020.4,5 Likewise,

Correspondence: Maria Casagrande several governments have adopted the same measures.4

Dipartimento di Psicologia Dinamica,

Clinica e Salute, “Sapienza” Università di COVID-19 pandemic affected the psychological well-being of the general

Roma, Via Degli Apuli, Rome, 100185, population. Several studies documented the mental-health outcomes of the pan-

Italy

Email maria.casagrande@uniroma1.it demic, particularly reporting an increase of distress,6–8 Post-Traumatic Stress

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com Nature and Science of Sleep 2021:13 191–199 191

DovePress © 2021 Casagrande et al. This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/

http://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S285854

terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). By accessing

the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed.

For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms (https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php).

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Casagrande et al Dovepress

Disorders’ symptoms (PTSD),9,10 anxiety,11,12 mood potential risk factors for poor sleep quality during lock-

diseases,11,12 and sleep disorders.8,13 In Italy, different down (eg, gender, level of education, occupational condi-

authors confirmed similar trends about the psychological tion, social capital).35,36, However, no research has

impact of the pandemic.14–20 Moreover, pandemic caused integrated the psychological variables into a model cap-

changes in daily habits and lifestyles (eg, eating habits, able to associate the pandemic dimensions and the quality

physical activity, and leisure activity21–23) linked to the of sleep.

more or less severe containment measures that exacerbated Moreover, it has never been clarified whether COVID-

the impact of COVID-19 on mental health.23 19-related variables (such as the diagnosis, the confine-

Nature and Science of Sleep downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 54.147.179.18 on 05-Nov-2021

One of the aspects highly affected by the pandemic ment, etc.) influenced sleep quality directly or indirectly

was sleep.16,24,25 Different studies evidenced alteration in and whether other aspects (such as mental-health vari-

both sleep quality and quantity. A recent meta-analysis ables) modulated it. The COVID-19 and the consequent

reported a prevalence of 32.2% of sleep disorders among measures taken to contain it could directly or indirectly

the general population.26 During the pandemic, modifica- alter sleep quality. Many psychological dimensions could

tions in sleep patterns, such as increased sleep medication play a relevant role in this relationship. Understanding

use, higher prevalence of insomnia, and a general decrease indirect associations of COVID-19 pandemic, more than

of perceived sleep quality were reported in association direct ones, would allow scheduling, specific interventions

with lifestyle changes due to the confinement.16,24,25. to improve the general population’s sleep quality.

Moreover, sleep disturbances were associated with higher Accordingly, this study aimed to assess the association

For personal use only.

levels of anxiety and depression and a greater incidence of between COVID-19-related aspects (ie, the diagnosis of

psychiatric disorders.26 COVID-19; the contact with people affected by the virus;

In Italy, an online survey conducted during the first 2 the day of confinement at home during the lockdown) and

weeks of lockdown reported poor sleep quality in about sleep quality, considering the moderator role of some psy-

six respondents out of ten (57.1%).16 Moreover, the mean chological variables identified by previous studies on the

scores of the questionnaire for the self-assessment of sleep effect of pandemic (ie, psychological well-being, anxiety,

quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index)27, adopted by the psychopathological symptoms, PTSD symptoms).11,14,16,18

study, indicated greater sleep disturbances in the respon- We hypothesized that COVID-19-related aspects influ-

dents’ sample than normative data from the general popu- enced both directly and indirectly via psychological vari-

lation. Other Italian studies reported similar ables the sleep quality. A worse sleep condition should be

results.15,20,24,28–30 For example, Marelli et al15 reported associated with higher COVID-19 exposure (ie, personal

increased sleep disturbances and insomnia, particularly in infection or direct contact with infected people) and home

students and workers. Cellini and colleagues24 highlighted confinement due to the pandemic spread. Furthermore, the

an alteration in sleep quality related to the changes in quality of sleep should be affected by the deterioration of

habits due to the home confinement, especially when the respondents’ psychological state, also influenced by

high levels of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoma- the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences, such as

tology were reported. Furthermore, Salfi and colleagues28 confinement and social distancing.

underlined that the Italian population transversely pre-

sented significant sleep disturbance after the stressful lock-

down period due to the pandemic. Materials and Methods

It is well known that sleep pattern is associated with Study Design and Participants

mental health. Sleep quality has a bidirectional relation- Data from the Italian population were collected by a web-

ship with stress, anxiety, and mood alteration.31 On the based cross-sectional survey that was broadcasted through

one hand, sleep disturbances exacerbate psychological dis- different platforms and mainstream social media between

tress; on the other hand, anxiety and depression impair the March 18th and April 2nd. After a brief presentation about

usual sleep habits.31,32 the study aims, electronic informed consent was requested

Many studies have assessed the different aspects of from each participant before starting the survey. A short ques-

sleep by providing important information about its asso- tionnaire collected information on some demographic and

ciation with the pandemic33 – such as the prevalence of COVID-19-related information, then standardized question-

sleep disturbance in different populations8,15,34 and the naires to evaluate psychological dimensions and sleep quality

192 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com Nature and Science of Sleep 2021:13

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress Casagrande et al

were administered. The survey lasted about 30 minutes, and all (0) to `extremely’ (4). Nine primary symptomatic dimen-

the data from respondents who completed the survey in less sions are measured: Somatization, Obsessive-Compulsive,

than 20 min were excluded to ensure a standard quality of Interpersonal Sensitivity, Depression, Anxiety, Anger-

questionnaires. The only inclusion criteria adopted were a Hostility, Phobic Anxiety, Paranoid Ideation, and

minimum age of 18 years and being Italian. If a participant Psychoticism. A Global Severity Index provides measures

withdrew from the survey before the end, no data were saved. of the overall psychological distress. Higher scores indi-

The 98% of the total respondents, who started the survey cate greater distress and psychopathological symptomatol-

signing the consent (2.286 participants out of 2.332), com- ogy. The internal consistency of SCL-90 is good for all its

Nature and Science of Sleep downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 54.147.179.18 on 05-Nov-2021

pleted it and were considered for the statistical analyses. subscales (an alpha value ranging between 0.70 and 0.96).

Participants were 1706 females and 580 males with a mean State and Trait Anxiety: the State-Trait Anxiety

age of 29.61 (standard deviation: 11.42) and an age range Inventory (STAI)41,42 includes 40-items. The items are

between 18 and 74 years. More specific information of the rated on 4-point Likert scales, ranging from 1 (not at all)

sample can be found in the previous study.17 to 4 (very much so). In both the State and Trait anxiety

scales, higher scores indicate greater anxiety levels. In the

Instrument and Measure present study, only State anxiety was considered. The

Demographic Information reliability of the STAI is adequate (alpha values ranging

To collect data on gender, age, education, occupation, between 0.90 and 0.93).

Territorial Areas (north, center or south of Italy), number COVID-19 PTSD related symptoms: the Post-Traumatic

For personal use only.

of inhabitants in own city (<2000; 2000–10,000; 10,000– Stress Disorder related to COVID-19 (COVID-19-PTSD)17

100,000; >100,000), a questionnaire including socio- was adopted. The questionnaire includes 19 items structured

demographic information was administered. on a 5-point Likert scale (from 0= not at all to 4= extremely).

Higher scores indicate a higher risk of PTSD occurrence.

COVID-19-Related Information

The COVID-19 PTSD demonstrated excellent internal con-

A section aimed to evaluate the personal experience with

sistency (alpha value= 0.94).

COVID-19 infection was included. If the respondents had

a COVID-19 diagnosis (options: “yes”, “no”, “I don’t

Sleep Quality

know”), and the number of days spent at home conse-

Sleep characteristics have been assessed through the

quently to the Italian government measures was reported.

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI),27,43 an 18-items

Moreover, three dichotomous (yes/no) questions were

questionnaire. The PSQI includes items evaluating sleep

focused on detecting the knowledge of people (1) affected

quality, sleep duration, sleep latency, habitual sleep effi-

by COVID-19, (2) admitted in intensive care units (ICU)

ciency, sleep disorders, the use of sleeping medications,

due to COVID-19, (3) dead for COVID-19. These three

and daytime dysfunctions. A global score indicates general

responses were converted into 1 (yes) and 0 (no) values

sleep quality/sleep disturbance. Higher scores indicate

and added together to obtain a global index.

poor sleep quality. The PSQI shows a high internal con-

Psychological Variables sistency (alpha= 0.83).

Psychological Well-Being

The Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWB- Ethical Consideration

I)37,38 consists of 22 items (6-point Likert scale), divided The study was conducted in accordance with the

into six dimensions: Anxiety, Depressed mood, Positive Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics

well-being, Self-control, General health, and Vitality, and a Committee of the Department of Dynamic and Clinical

global score of well-being. Higher scores indicating greater Psychology, “Sapienza” University of Rome (protocol

well-being and lower distress. The internal consistency of number: 0000266). To guarantee anonymity, no data

the questionnaire is adequate (alpha value higher than 0.74). which could allow the identification of participants were

collected.

Psychological Symptomatology

The Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90)39,40 was adminis- Statistical Analysis

tered to assess psychological symptomatology. The items Descriptive statistics of demographic variables were

are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from `not at all’ reported. The Structural equation modeling (SEM) was

Nature and Science of Sleep 2021:13 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

193

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Casagrande et al Dovepress

performed in R studio software to estimate a path model particular, the presence of COVID-19 infection in respon-

that can explain the direct relation between COVID-19- dents determined low sleep quality through all the psycho-

related variables and sleep quality and the possible mod- logical variables (all p< 0.05), except for the State Anxiety

erator effect of psychological variables. (p= 0.06). The days spent at home influenced the sleep

To check the adequate sample size for the study, pre- quality through the mediation of PTSD symptomatology

vious studies were analyzed, and power analysis was con- (p< 0.05) and general psychological symptomatology (p<

ducted. According to some authors,44 a sample of 2.000 0.05), while there is no mediation role of psychological

participants for the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) distress (p= 0.10) and state anxiety (p= 0.15). The effect of

Nature and Science of Sleep downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 54.147.179.18 on 05-Nov-2021

analysis was considered a large sample condition. knowledge of people affected by COVID-19 on sleep

Moreover, a power analysis conducted specifically for quality was significantly mediated by psychological dis-

survey online (CL: 95.5%; CI: 5), considering the target tress (p< 0.05) and PTSD symptomatology (p< 0.001), but

population (ie, adults between 18 and 74 years of age with not by state anxiety (p= 0.06) and general psychological

internet access),45 confirmed that 2000 respondents repre- symptomatology (p= 0.10) (see Table 4). We also con-

sent an adequate sample size for statistical analyses. trolled the model for age and gender, considered as con-

The robust maximum likelihood estimator (MRL) was founding variables, but these variables did not produce

used for parameter estimation because it is most robust to significant changes in the texted model.

the normality assumption violations. Figure 1 reports the path diagram.

We also controlled the model for age and gender as

For personal use only.

possible confounding variables. The χ2, the comparative

fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and the root- Discussion

mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) indices This study aimed to assess the association between

were employed to determine whether the models fit the COVID-19-related aspects and sleep quality, considering

data. Good model fit was determined by the cut-off of 0.90 the moderator role of some psychological variables in this

value for CFI and TLI and 0.08 for the RMSEA. relationship.

Many studies have shown a worsening of sleep quality

and a high prevalence of sleep disorders during the first

Results phase of the COVID-19 pandemic spread.8,11,16,25 Lower

Demographic Characteristics sleep quality and increased sleep disturbances were con-

Demographic characteristics of the respondents are firmed by Italian15,16,19,24,28 and international8,13,25 stu-

reported in Table 1. The sample included 74.6% of dies. However, no study has clarified whether this

women. The age range most represented was 18–29 impairment of sleep quality was directly determined by

years (68.6%), and the respondents presented generally the variables associated with COVID-19 (eg, the risk of

high levels of education. The 51.4% of the respondents infection; the confinement at home) or whether it was due

are settled in the South, 25% in the Centre, and 23.6.% in to the altered psychological condition caused by the pan-

the North of Italy. demic. Accordingly, this study examined the role of dif-

ferent psychological variables (psychological well-being,

Path Model COVID-19 PTSD related symptoms, psychological symp-

The path model fit adequately the overall data, χ2 (df= 14) tomatology, and state of anxiety) as potential mediators of

= 314.42, p< 0.0001, CFI= 0.95, TLI= 92, RMSEA= 0.08, the relationship between some aspects specifically related

90% CI [0.07, 0.09]. to the COVID-19 pandemic (ie, to have a COVID-19

The analysis revealed that lower sleep quality was diagnosis, number of days spent at home after the confine-

directly related to the days spent in confinement at home ment measures, knowledge of people affected at different

(p= 0.01) and the knowledge of people affected by the degrees by COVID-19) and self-reported sleep quality in

COVID-19 (p= 0.03), but not to a COVID-19 diagnosis an Italian sample during the lockdown. The principal

(p= 0.51) (see Table 2). objectives were to clarify whether some COVID-19-

Considering the total indirect effects, all the three related aspects, directly and indirectly, affect sleep quality

variables COVID-19-related were significantly associated during this health emergency through their influence on

with lower sleep quality (all p< 0.05) (see Table 3). In psychological states.

194 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com Nature and Science of Sleep 2021:13

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress Casagrande et al

Table 1 Demographic Characteristics of the Sample Table 1 (Continued).

Total Sample (N=

Total Sample (N=

2286)

2286)

Sex, n (%)

Knowledge of people died for COVID-19

Man 580 (25.4)

Yes 112 (4.9)

Woman 1706 (74.6)

No 2174 (95.1)

Age, n (%)

Note: From: Forte et al 2020.10

18–29 years old 1568 (68.6) Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

Nature and Science of Sleep downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 54.147.179.18 on 05-Nov-2021

30–49 years old 485 (21.2)

>50 years old 233 (10.2)

Education, n (%) Results confirm a direct effect of some aspects ascribable

Until middle School 97 (4.2) to the pandemic.16,18 The first period of the pandemic spread

High School 1135 (49.6)

in Italy and, consequently, the first phase of the lockdown, the

Undergraduate

Health care 246 (10.8)

confinement at home, and the consequential social distan-

Other 658 (28.8) cing, directly impaired the participants’ sleep quality.

Post-graduated COVID-19-related aspect and the confinement at home also

Health care 63 (2.8)

Other 87 (3.8)

affected the participants’ psychological condition, confirm-

ing a mediator role of psychological distress (PGWB), PTSD

Occupation, n (%)

symptoms (COVID-19-PTSD), and psychological symp-

For personal use only.

Student 1071 (46.8)

Employed 687 (30.1) toms (SCL-90) on self-reported sleep quality.

Unemployed 278 (12.2) Although a high level of anxiety during the emergency

Self-Employed 222 (9.7)

was reported, it does not appear to play a modulator role in

Retired 28 (1.22)

sleep quality.16,18,34 This result is surprising and unex-

Territorial areas

pected. It is proved that anxiety negatively affects sleep

North Italy 540 (23.6)

Centre Italy 571 (25.0) quality;46 however, this role did not emerge in our model.

South Italy 1175 (51.4) This result may depend on the weight assumed by other

Number of inhabitants in own city, n (%) psychological variables such as distress or PTSD symp-

< 2.000 124 (5.4) toms COVID-19 related. Accordingly, many Italians

2.000–10.000 451 (19.7)

experienced the first period of the pandemic spread and

10.000–100.000 936 (50.0)

> 100.000 775 (33.9)

the lockdown as a traumatic event. In fact, in this period, a

high percentage of PTSD symptomatology (29.5%) was

Quarantine experience, n (%)

Alone 2054 (89.9)

found in the Italian population.17,18

Others 232 (10.1) Generally, evidence of an impairment of sleep qual-

Infection by the virus

ity and increased sleep disturbances during the

Yes 9 (0.4) COVID-19 pandemic has been reported in the general

No 1703 (74.5) population and specific conditions (eg, health care

Do not know 574 (25.1)

workers).15,16,19,24,47,48 This worsening was described

Direct contact with people infected by COVID-19 in heterogeneous samples (eg, university students,

Yes 40 (1.7)

health care professionals, people subjected to the quar-

No 1438 (63.0)

Do not know 808 (35.3) antine dispositions, general population), and it was

often associated with other psychological conditions,

Knowledge of people infected by COVID-19

Yes 549 (24.0) such as anxiety or PTSD symptomatology.

No 1737 (76.0) Our previous work16 highlighted that some aspects

Knowledge of people in ICU for COVID-19 related to COVID-19 would represent possible risk factors

Yes 177 (7.7) for sleep disturbances, specifically the uncertainty regard-

No 2109 (92.3)

ing direct contact with individuals infected by COVID-19

(Continued) and the knowledge of people that died because of COVID-

Nature and Science of Sleep 2021:13 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

195

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Casagrande et al Dovepress

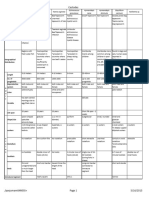

Table 2 The Direct Effect of COVID-19-Related Variables on Sleep Quality

Estimate Std.Err z-value p

Infected by COVID-19 -> Sleep Quality −0.03 0.03 −0.065 0.51

Days spent at home in confinement -> Sleep Quality 0.01 0.003 3.89 0.001

Knowledge of people infected by COVID-19* -> Sleep Quality 0.05 0.02 2.09 0.03

Note: *Infected, in ICU or dead because of COVID-19.

Nature and Science of Sleep downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 54.147.179.18 on 05-Nov-2021

Table 3 The Global Indirect Effect of COVID-19-Related Variables on Sleep Quality

Estimate Std. Err z-value p

Infected by COVID-19 -> Sleep Quality 0.09 0.2 3.24 0.001

Days spent at home in confinement -> Sleep Quality 0.005 0.002 2.23 0.02

Knowledge of people infected by COVID-19* -> Sleep Quality 0.05 0.02 2.63 0.01

Note: *Infected, in ICU or dead because of COVID-19.

Table 4 Indirect Effects of COVID-19-Related Variables on Sleep Quality

Estimate Std. Err z-value p

For personal use only.

Affection by COVID-19 -> Psychological Well-Being -> Sleep Quality 0.06 0.01 3.30 0.001

Affection by COVID-19 -> COVID-PTSD -> Sleep Quality 0.02 0.01 1.91 0.04

Affection by COVID-19 -> State Anxiety -> Sleep Quality −0.01 0.005 −1.90 0.06

Affection by COVID-19 -> Psychological Symptomatology-> Sleep Quality 0.02 0.007 2.28 0.02

Days spent at home -> Psychological Well-Being -> Sleep Quality 0.002 0.001 1.63 0.10

Days spent at home -> COVID-PTSD -> Sleep Quality 0.002 0.001 2.22 0.02

Days spent at home -> State Anxiety -> Sleep Quality −0.001 0.002 −1.44 0.15

Days spent at home -> Psychological Symptomatology-> Sleep Quality 0.001 0.001 2.21 0.02

Knowledge of people infected by COVID-19* -> Psychological Well-Being -> Sleep Quality 0.02 0.01 1.89 0.04

Knowledge of people infected by COVID-19* -> COVID-PTSD -> Sleep Quality 0.03 0.01 3.26 0.001

Knowledge of people infected by COVID-19* -> State Anxiety -> Sleep Quality −0.01 0.01 −1.89 0.06

Knowledge of people infected by COVID-19* -> Psychological Symptomatology-> Sleep Quality 0.01 0.01 1.63 0.10

Note: *Infected, in ICU or dead because of COVID-19.

19. Accordingly, a recent study reported that fear of con- associated with the COVID-19 experience appears to

tagion impacts individuals’ mental health, including con- have a mediating role in sleep quality. This result would

sequences on the quality of sleep.49 Our current study confirm previous findings that have shown high PTSD

added some information on this aspect. It seems that symptoms in conditions of severe emergencies, epidemics,

there are multiple aspects associated with the pandemic and, more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic.16–18,50

experience that appears to affect sleep quality in different Moreover, these symptoms would be directly related to

ways. The uncertainty or the confirmation of a COVID-19 sleep quality.51,52 These results appear important and need

diagnosis indirectly influences, via psychological dimen- to be considered from a clinical perspective given the

sions, sleep quality. However, other aspects related to this findings that detected high rates of COVID-related PTSD

exceptional event, as the days spent in confinement at in the worldwide and Italian populations.9,18,53,54

home (ie, social isolation) and the knowledge of people A similar trend was reported considering the psycho-

affected at different severities by the COVID-19, including logical symptomatology measured with SCL-90. The

also dead people (ie, the fear of the impact of the infec- COVID-19 emergency exacerbates the psychopathological

tion) directly influences sleep quality. symptoms, in line with previous evidence that compared

Considering the moderator effects of psychological psychopathological symptoms measured during the

variables, some interesting considerations can be COVID-19 pandemic with normative data from the gen-

addressed. The high post-traumatic symptomatology eral population.18 In this study, we underlined the

196 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com Nature and Science of Sleep 2021:13

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress Casagrande et al

Nature and Science of Sleep downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 54.147.179.18 on 05-Nov-2021

For personal use only.

Figure 1 The path diagram.

influence of the psychopathological condition on sleep behavior, maladaptive eating habits) should be done

quality without ignoring the role of COVID-19 experience according to the results of previous studies highlighting

and reporting a strong link between the environmental the role of certain demographic or lifestyle variables as

situation and the psychological condition. possible risk factors for sleep quality.9 Moreover, the

The general psychological well-being that, inversely, adoption of a self-report measure to evaluate the quality

can be considered as an index of psychological distress, and quantity of sleep might represent a limit in reliability

again, acts as a mediator of the relationship between and may not highlight specific characteristics of the sleep

COVID-19 variables and sleep quality. The worsening of pattern during a pandemic. Similarly, the adoption of a

psychological well-being during the COVID-19 emer- questionnaire to assess psychological variables could not

gency impacted sleep quality and sleep disturbances. identify mental illnesses, representing a further limitation

Although this study reported some interesting findings, of the study.

certain limitations should be highlighted. First, the sam-

ple’s recruitment was carried out with an online survey, Conclusions

and the poor control of self-reported measures represents a In the face of an unprecedented medical emergency, which

limit in the path model generalizability. The cross-sec- has directly impacted the fear of contagion and the indirect

tional design is another limit because it did not allow risks associated with it, the present findings highlight the

understanding the causal nature of the relationship and importance of also considering the psychological effects.

whether this relationship is confirmed or modulated over The COVID-19 spread has undoubtedly influenced the

time and with the changes in the pandemic situation. people’s psychological state, but it has also played a med-

However, the study aimed to highlight the Italian popula- iating role in the pandemic consequences. In this study, the

tion’s state in the first days after the lockdown; therefore, a central focus was on the quality of sleep, which directly

longitudinal design was impossible to use. Furthermore, influences many daily activities, and it is involved, at

greater control of potentially confounding variables such multiple levels, in the psychological,55,56 cognitive57,58

as gender, occupational status, age, medical conditions, and physical59 well-being of individuals. Interventions to

lifestyle changes involving health behavior (eg, sedentary promote a good quality of sleep and reduce sleep disorders

Nature and Science of Sleep 2021:13 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

197

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Casagrande et al Dovepress

in these critical phases cannot ignore aspects such as 8. Fu W, Wang C, Zou L, et al. Psychological health, sleep quality, and

coping styles to stress facing the COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Transl

distress, psychological symptoms, and PTSD symptoms.

Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):1–9. doi:10.1038/s41398-020-00913-3

All these aspects, being influenced by the COVID-19 9. Liu N, Zhang F, Wei C, et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS

experience and being mediators of the impact on sleep during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: gender differ-

ences matter. Psych Res. 2020;112921.

quality, must be well evaluated before implementing inter- 10. Karatzias T, Shevlin M, Murphy J, et al. Posttraumatic stress symp-

ventions to solve sleep diseases related to this extraordin- toms and associated comorbidity during the COVID-19 pandemic in

ary event, both in the medium and long terms. Ireland: a population-based study. J Trauma Stress. 2020;33(4):365–

370. doi:10.1002/jts.22565

To counteract the increase in sleep disturbances and the

Nature and Science of Sleep downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 54.147.179.18 on 05-Nov-2021

11. Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, et al. Prevalence of stress,

worsening of sleep quality due to pandemic, it would be anxiety, depression among the general population during the

COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob

useful to adopt countermeasures, such as general sleep

Health. 2020;16(1):1–11.

hygiene programs (eg, maintaining sleep and waking 12. Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing

times, adequate physical activity, proper nutrition, good literature. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;102066.

13. Voitsidis P, Gliatas I, Bairachtari V, et al. Insomnia during the

organization of the day, avoiding overexposure to news COVID-19 pandemic in a Greek population. Psych Res.

COVID-19 related, especially in the evening). However, 2020:113076.

14. Mazza C, Ricci E, Biondi S, et al. A nationwide survey of psycho-

our results show that this emergency and the social distan-

logical distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pan-

cing and confinement at home norms lead to psychological demic: immediate psychological responses and associated factors.

diseases that worsen sleep quality. Therefore, governments Int J Environ Res. 2020;17(9):3165.

15. Marelli S, Castelnuovo A, Somma A, et al. Impact of COVID-19

should provide clinical and counseling centers and online lockdown on sleep quality in university students and administration

For personal use only.

platforms consisting of psychologists and sleep experts to staff. J Neurol. 2020;1–8.

improve the psychological condition and provide adequate 16. Casagrande M, Favieri F, Tambelli R, Forte G. The enemy who

sealed the world: effects quarantine due to the COVID-19 on sleep

sleep hygiene support. quality, anxiety, and psychological distress in the Italian population.

Sleep Med. 2020;75:12–20. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.011

17. Forte G, Favieri F, Tambelli R, Casagrande M. COVID-19 Pandemic

Acknowledgments in the Italian Population: validation of a Post-Traumatic Stress

This work was supported by a grant from the “Sapienza” Disorder Questionnaire and Prevalence of PTSD Symptomatology.

Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):4151. doi:10.3390/

University of Rome.

ijerph17114151

18. Forte G, Favieri F, Tambelli R, Casagrande M. The Enemy Which

Disclosure Sealed the World: effects of COVID-19 Diffusion on the

Psychological State of the Italian Population. J Clin Med. 2020;9

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work. (6):1802. doi:10.3390/jcm9061802

19. Gualano MR, Lo Moro G, Voglino G, et al. Effects of Covid-19

lockdown on mental health and sleep disturbances in Italy. Int J

References Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(13):4779. doi:10.3390/

1. Serafini G, Parmigiani B, Amerio A, Aguglia A, Sher L, Amore M. ijerph17134779

The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the 20. Rossi R, Socci V, Talevi D, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown

general population. QJM. 2020;113(8):531–537. doi:10.1093/qjmed/ measures impact on mental health among the general population in

hcaa201 Italy. Front Psychiat. 2020;11:790. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00790

2. Ali I, Alharbi OM. COVID-19: disease, management, treatment, and 21. Di Renzo L, Gualtieri P, Pivari F, et al. Eating habits and lifestyle

social impact. Sci Total Environ. 2020;728:138861. doi:10.1016/j. changes during COVID-19 lockdown: an Italian survey. J Transl

scitotenv.2020.138861 Med. 2020;18(1):1–15. doi:10.1186/s12967-020-02399-5

3. Saladino V, Algeri D, Auriemma V. The psychological and social 22. Carriedo A, Cecchini JA, Fernandez-Rio J, Méndez-Giménez A.

impact of Covid-19: new perspectives of well-being. Front Psychol. COVID-19, psychological well-being and physical activity levels in

2020;11:2550. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577684 older adults during the nationwide lockdown in Spain. Am J Geriatr

4. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situa- Psychiatry. 2020;28(11):1146–1155. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2020.08.007

tion reports. 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/dis 23. Jacob L, Tully MA, Barnett Y, et al. The relationship between

eases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/. Accessed November physical activity and mental health in a sample of the UK public: a

20, 2020. cross-sectional study during the implementation of COVID-19 social

5. Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Epicentro. Coronavirus. 2020. Available distancing measures. Ment Health Phys Act. 2020;19:100345.

from: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/. Accessed November doi:10.1016/j.mhpa.2020.100345

20, 2020. 24. Cellini N, Canale N, Mioni G, Costa S. Changes in sleep pattern,

6. Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of sense of time and digital media use during COVID-19 lockdown in

psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epi- Italy. J Sleep Res. 2020;e13074.

demic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatry. 25. Jahrami H, BaHammam AS, Bragazzi NL, Saif Z, Faris M, Vitiello MV.

2020;33(2). doi:10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213 Sleep problems during COVID-19 pandemic by population: a systema-

7. Petzold MB, Bendau A, Plag J, et al. Risk, resilience, psychological tic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;jcsm–8930.

distress, and anxiety at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 26. Sher L. COVID-19, anxiety, sleep disturbances and suicide. Sleep

Germany. Brain Behav. 2020;10(9):e01745. doi:10.1002/brb3.1745 Med. 2020;70:124. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2020.04.019

198 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com Nature and Science of Sleep 2021:13

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Dovepress Casagrande et al

27. Buysse DJ, Reynolds III CF, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh sleep 44. Sivo SA, Fan X, Witta EL, Willse JT. The search for” optimal” cutoff

quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. properties: fit index criteria in structural equation modeling. J Exp

Psych Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 Educ. 2006;74(3):267–288. doi:10.3200/JEXE.74.3.267-288

28. Salfi F, Lauriola M, Amicucci G, et al. Gender-related time course of 45. Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. Datie Microdati Popolazione Italiana.

sleep disturbances and psychological symptoms during the COVID- Available from: https://www.istat.it/it/popolazione-e-famiglie.

19 lockdown: a longitudinal study on the Italian population. Accessed November 20, 2020.

Neurobiol Stress. 2020;13:100259. doi:10.1016/j.ynstr.2020.100259 46. Cox RC, Olatunji BO. A systematic review of sleep disturbance in

29. Morin CM, Carrier J. The acute effects of the COVID-19 pandemic anxiety and related disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 2016;37:104–129.

on insomnia and psychological symptoms. Sleep Med. 2020;S1389– doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.12.001

9457(20):30261–30266. 47. Majumdar P, Biswas A, Sahu S. COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown:

Nature and Science of Sleep downloaded from https://www.dovepress.com/ by 54.147.179.18 on 05-Nov-2021

30. Franceschini C, Musetti A, Zenesini C. Poor quality of sleep and its cause of sleep disruption, depression, somatic pain, and increased

consequences on mental health during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. screen exposure of office workers and students of India. Chronob Int.

Psyarxiv Preprint. 2020. 2020;1–10.

31. Friedrich A, Schlarb AA. Let’s talk about sleep: a systematic review 48. Zhuo K, Gao C, Wang X, et al. Stress and sleep: a survey based on

of psychological interventions to improve sleep in college students. J wearable sleep trackers among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan

Sleep Res. 2018;27(1):4–22. doi:10.1111/jsr.12568 during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gen Psych. 2020;33(3).

32. Fang H, Tu S, Sheng J, Shao A. Depression in sleep disturbance: a 49. Fitzpatrick KM, Harris C, Drawve G. Fear of COVID-19 and the

review on a bidirectional relationship, mechanisms and treatment. J mental health consequences in America. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12

Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(4):2324–2332. doi:10.1111/jcmm.14170 (S1):17–21. doi:10.1037/tra0000924

33. Altena E, Baglioni C, Espie CA, et al. Dealing with sleep problems 50. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact

during home confinement due to the COVID-19 outbreak: practical of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence.

recommendations from a task force of the European CBT-I academy. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)

J Sleep Res. 2020;e13052. 30460-8

34. Huang Y, Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symp- 51. Germain A, Hall M, Krakow B, et al. A brief sleep scale for post-

toms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web- traumatic stress disorder: Pittsburgh sleep quality index addendum

For personal use only.

based cross-sectional survey. Psych Res. 2020;288:112954. for PTSD. J Anxiety Disord. 2005;19(2):233–244. doi:10.1016/j.

doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954 janxdis.2004.02.001

35. Xiao H, Zhang Y, Kong D, et al. The effects of social support on 52. Strasshofer DR, Pacella ML, Irish LA, et al. The role of perceived

sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with coronavirus dis- sleep quality in the relationship between PTSD symptoms and gen-

ease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China. Med eral mental health. Mental Health Prev. 2017;5:27–32. doi:10.1016/j.

Sci Monit. 2020;26:e923549–1. doi:10.12659/MSM.923921 mhp.2017.01.001

36. Ernstsen L, Havnen A. Mental health and sleep disturbances in 53. Tang W, Hu T, Hu B, et al. Prevalence and correlates of PTSD and

physically active adults during the COVID-19 lockdown in depressive symptoms one month after the outbreak of the COVID-19

Norway: does change in physical activity level matter? Sleep Med. epidemic in a sample of home-quarantined Chinese university stu-

2020. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2020.08.030 dents. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:1–7. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.009

37. Dupuy HJ, Wenger NK, Mattson ME, Fuberg CP. Assessment of 54. Fekih-Romdhane F, Ghrissi F, Abbassi B, et al. Prevalence and

Quality of Life in Clinical Trials of Cardiovascular Therapies. New predictors of PTSD during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from

York: Le Jacq; 1984. a Tunisian community sample. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113131.

38. Grossi E, Mosconi P, Groth N, Niero M, Apolone G. Questionario doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113131

Psychological General Well.-Being Index: Versione Italiana. Milano: 55. Saunders EF, Fernandez-Mendoza J, Kamali M, et al. The effect of

Istituto Farmacologiao Mario Negri; 2002. poor sleep quality on mood outcome differs between men and

39. Derogatis LR, Cleary PA. Confirmation of the dimensional structure women: a longitudinal study of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord.

of the SCL-90: a study in construct validation. J Clin Psych. 1977;33 2015;180:90–96. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.048

(4):981–989. doi:10.1002/1097-4679(197710)33:4<981::AID- 56. Tkachenko O, Olson EA, Weber M, et al. Sleep difficulties are

JCLP2270330412>3.0.CO;2-0 associated with increased symptoms of psychopathology. Exp Brain

40. Cassano GB, Conti L, Levine J. SCL-90. In Repertorio Delle Scale di Res. 2014;232(5):1567–1574. doi:10.1007/s00221-014-3827-y

Valutazione in Psichiatria. Firenze, Italy: SEE; 1999:325–332. 57. Nebes RD, Buysse DJ, Halligan EM, et al. Self-reported sleep quality

41. Spielberger CD. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults. Palo Alto, predicts poor cognitive performance in healthy older adults. J

CA: Mind Garden; 1983. Gerontol. 2009;64B(2):180–187. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbn037

42. Pedrabissi L, Santinello M. Verifica Della Validità Dello STAI forma 58. Porter VR, Buxton WG, Avidan AY. Sleep, cognition and dementia.

Y di Spielberger. Firenze, Italy: Giunti Organizzazioni Speciali; 1989. Curr Psych Rep. 2015;17(12):97. doi:10.1007/s11920-015-0631-8

43. Curcio G, Tempesta D, Scarlata S, et al. Validity of the Italian version 59. Gothe NP, Ehlers DK, Salerno EA, et al. Physical activity, sleep and

of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI). Neurol Sci. 2013;34 quality of life in older adults: influence of physical, mental and social

(4):511e9. doi:10.1007/s10072-012-1085-y well-being. Behav Sleep Med. 2019;1–12.

Nature and Science of Sleep Dovepress

Publish your work in this journal

Nature and Science of Sleep is an international, peer-reviewed, open The manuscript management system is completely online and

access journal covering all aspects of sleep science and sleep med- includes a very quick and fair peer-review system, which is all easy

icine, including the neurophysiology and functions of sleep, the to use. Visit http://www.dovepress.com/testimonials.php to read real

genetics of sleep, sleep and society, biological rhythms, dreaming, quotes from published authors.

sleep disorders and therapy, and strategies to optimize healthy sleep.

Submit your manuscript here: https://www.dovepress.com/nature-and-science-of-sleep-journal

Nature and Science of Sleep 2021:13 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

199

DovePress

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

You might also like

- List of Medical Triads and Pentads - WikipediaDocument3 pagesList of Medical Triads and Pentads - WikipediaSubhajitPaul100% (1)

- Rating of Perceived Exertion For Quantification of The Intensity of Resistance Exercise 2329 9096.1000172Document4 pagesRating of Perceived Exertion For Quantification of The Intensity of Resistance Exercise 2329 9096.1000172joseNo ratings yet

- JPR 231737 Hypnosis Associated With 3d Immersive Virtual Reality TechnoDocument10 pagesJPR 231737 Hypnosis Associated With 3d Immersive Virtual Reality Techno026II1Muhammad Avicenna AdjiNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Related Emotional Stress and Bedtime Procrastination Among College Students in China A Moderated Mediation ModelDocument11 pagesCOVID-19 Related Emotional Stress and Bedtime Procrastination Among College Students in China A Moderated Mediation ModelSDN 2 KarangrejaNo ratings yet

- Covid DepressionDocument10 pagesCovid Depressiondidi monroeNo ratings yet

- Bragazzi - A Proposal For Including NomophobiaDocument6 pagesBragazzi - A Proposal For Including NomophobiaLeo GalileoNo ratings yet

- Depression Dove Neuropsychiatric Disease and TreatmentDocument7 pagesDepression Dove Neuropsychiatric Disease and TreatmentDelelegn EmwodewNo ratings yet

- Detection of Glaucoma and Other Vision-Threatening Ocular Diseases in The Population Recruited at Specific Health Checkups in JapanDocument8 pagesDetection of Glaucoma and Other Vision-Threatening Ocular Diseases in The Population Recruited at Specific Health Checkups in JapanPuskesmas Purwokerto SelatanNo ratings yet

- A Narrative Review of Binge Eating Disorder in Adolescence: Prevalence, Impact, and Psychological Treatment StrategiesDocument14 pagesA Narrative Review of Binge Eating Disorder in Adolescence: Prevalence, Impact, and Psychological Treatment StrategiesKariena PermanasariNo ratings yet

- PRBM 275593 The Psychological Impacts of Covid 19 Pandemic Among UniversDocument9 pagesPRBM 275593 The Psychological Impacts of Covid 19 Pandemic Among UniversMykhaela Louize GumbanNo ratings yet

- Fphys 12 755322Document11 pagesFphys 12 755322Khristle DavidNo ratings yet

- Hypno Death Experiences Death ExperienceDocument5 pagesHypno Death Experiences Death Experiencepawel.tryniszewskiNo ratings yet

- Out-of-Body Experience Induced by Hypnotic Suggestions: An Exploratory Neurophenomenological StudyDocument36 pagesOut-of-Body Experience Induced by Hypnotic Suggestions: An Exploratory Neurophenomenological StudyDania MarianoNo ratings yet

- Hyperarousal and Sleep Reactivity in Insomnia - Current InsightsDocument9 pagesHyperarousal and Sleep Reactivity in Insomnia - Current InsightsRicardo Vio LeonardiNo ratings yet

- NDT 147315 The Walsh Family Resilience Questionnaire The Italian Versi 121517Document13 pagesNDT 147315 The Walsh Family Resilience Questionnaire The Italian Versi 121517Hanny ErchanisNo ratings yet

- Psychometric Properties of The Spanish Version of The Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation - Outcome MeasureDocument10 pagesPsychometric Properties of The Spanish Version of The Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation - Outcome MeasureSilvana AcostaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Red Light On Sleep InertiaDocument13 pagesEffects of Red Light On Sleep InertiaMonica SaavedraNo ratings yet

- Illness Denial Questionnaire For Patients andDocument8 pagesIllness Denial Questionnaire For Patients andNicole PrincicNo ratings yet

- HypothesisDocument2 pagesHypothesisIvy TiwanaNo ratings yet

- Psychological Distress Amongst Health Workers and The General Public During The COVID-19 Pandemic in Saudi Arabia (Kuesioner CPDI)Document10 pagesPsychological Distress Amongst Health Workers and The General Public During The COVID-19 Pandemic in Saudi Arabia (Kuesioner CPDI)Febri YolandaNo ratings yet

- Articulo 4 Adolecnete SDocument14 pagesArticulo 4 Adolecnete SguadaluperoderoNo ratings yet

- Fpsyg 12 616426Document7 pagesFpsyg 12 616426Fabrizio ForlaniNo ratings yet

- JPR 129872 Chronic Stress Moderates The Impact of Social Exclusion On P - 051717Document8 pagesJPR 129872 Chronic Stress Moderates The Impact of Social Exclusion On P - 051717imam mulyadiNo ratings yet

- Tidur 12Document7 pagesTidur 12putputNo ratings yet

- Laporan Penugasan EBPHDocument25 pagesLaporan Penugasan EBPHHOSEA JONA YULIADANo ratings yet

- JoernalDocument7 pagesJoernalyennaputriNo ratings yet

- Sleep Physiology and Pathology: Pertinence To Psychiatry: Constantin R. Soldatos & Thomas J. PaparrigopoulosDocument16 pagesSleep Physiology and Pathology: Pertinence To Psychiatry: Constantin R. Soldatos & Thomas J. PaparrigopoulosMatthew ChristopherNo ratings yet

- Marques Et Al - 2018 - Development and Characterization of A Nanoemulsion Containing Propranolol For Topical DeliveryDocument11 pagesMarques Et Al - 2018 - Development and Characterization of A Nanoemulsion Containing Propranolol For Topical DeliveryEvandro D'OrnellasNo ratings yet

- Hypno Death Experiences Death Experiences During Hypnotic Life RegressionsDocument6 pagesHypno Death Experiences Death Experiences During Hypnotic Life RegressionsmalwinatmdNo ratings yet

- Sleep Better Think Better The Effect of CBT I and HT I On Sleep and Subjective and Objective Neurocognitive Performance in University Students WithDocument18 pagesSleep Better Think Better The Effect of CBT I and HT I On Sleep and Subjective and Objective Neurocognitive Performance in University Students WithAndres VidesNo ratings yet

- Basics of EpidemiologyDocument1 pageBasics of EpidemiologyJordan ChizickNo ratings yet

- A Study of Insomnia Among Psychiatric Out Patients in Lagos Nigeria 2167 0277.1000104Document5 pagesA Study of Insomnia Among Psychiatric Out Patients in Lagos Nigeria 2167 0277.1000104Ilma Kurnia SariNo ratings yet

- Insomnia and Psychological Reactions During The COVID-19 Outbreak in ChinaDocument2 pagesInsomnia and Psychological Reactions During The COVID-19 Outbreak in ChinaMartha OktaviaNo ratings yet

- Fnhum 15 711279Document14 pagesFnhum 15 711279ANTONIO REYES MEDINANo ratings yet

- Mental Health Risk Factors During The First Wave of The Covid 19 PandemicDocument6 pagesMental Health Risk Factors During The First Wave of The Covid 19 PandemicFrancine SilvaNo ratings yet

- Sleep Disorder 2Document7 pagesSleep Disorder 2nindya prahasariNo ratings yet

- ARTIGO - HOWARD & THORNICROFT - Psychosocial Characteristics and Needs of Mothers With Psychotic DisordersDocument7 pagesARTIGO - HOWARD & THORNICROFT - Psychosocial Characteristics and Needs of Mothers With Psychotic DisordersVagner Marchezoni MedeirosNo ratings yet

- Sleep-Wake Cycle Disturbances and Neun-Altered Expression in Adult Rats After Cannabidiol Treatments During AdolescenceDocument11 pagesSleep-Wake Cycle Disturbances and Neun-Altered Expression in Adult Rats After Cannabidiol Treatments During AdolescenceGabriel MontoyaNo ratings yet

- Fnsys 16 803904 2 PDFDocument17 pagesFnsys 16 803904 2 PDFmkuntzNo ratings yet

- 493-Article Text-1314-1-10-20210718Document8 pages493-Article Text-1314-1-10-20210718aris dwiprasetyaNo ratings yet

- Depression and Associated Factors Jimma Dove Neuropsychiatric Diasease and TreatmentDocument10 pagesDepression and Associated Factors Jimma Dove Neuropsychiatric Diasease and TreatmentDelelegn EmwodewNo ratings yet

- Child Sleep Problems Affect MoDocument17 pagesChild Sleep Problems Affect MosandykartikapNo ratings yet

- Composite Diagnostic: The International InterviewDocument9 pagesComposite Diagnostic: The International InterviewLibros LibrosNo ratings yet

- The Acute Effects of The COVID-19 Pandemic On Insomnia and Psychological SymptomsDocument2 pagesThe Acute Effects of The COVID-19 Pandemic On Insomnia and Psychological Symptomschristiancraig1987No ratings yet

- Paul Schdlich Erlacher 2014 Visual TactileDocument7 pagesPaul Schdlich Erlacher 2014 Visual Tactilehappy crackNo ratings yet

- Schumann Resonance Sleep DeviceDocument12 pagesSchumann Resonance Sleep DeviceOlegGrigorevNo ratings yet

- The Psychological Impact of The COVID-19 Outbreak On Health Professionals: A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument9 pagesThe Psychological Impact of The COVID-19 Outbreak On Health Professionals: A Cross-Sectional StudyMáthé AdriennNo ratings yet

- To Study The Mystery of Sleep, Sleep Disorder or Insomnia and Its Effect On Physical and Mental HealthDocument3 pagesTo Study The Mystery of Sleep, Sleep Disorder or Insomnia and Its Effect On Physical and Mental HealthInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Exploring The Impact of Sleep Paralysis On The Well Being of Young AdultsDocument5 pagesExploring The Impact of Sleep Paralysis On The Well Being of Young AdultsEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Rossi Et Al 2021Document8 pagesRossi Et Al 2021Elianne PauliNo ratings yet

- The Role of The Circadian SystDocument17 pagesThe Role of The Circadian SystrizkyardiwinataNo ratings yet

- COVID-19: PTSD Symptoms in Greek Health Care ProfessionalsDocument8 pagesCOVID-19: PTSD Symptoms in Greek Health Care ProfessionalsmaryNo ratings yet

- Body Image and Quality of Life in A Spanish PopulationDocument10 pagesBody Image and Quality of Life in A Spanish PopulationDesiré Abrante RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Fpsyt 12 605676Document13 pagesFpsyt 12 605676Kevin EsquivelNo ratings yet

- SLEEP - Scientific America - The Power of Sleep - Oct2015Document7 pagesSLEEP - Scientific America - The Power of Sleep - Oct2015Sean DrewNo ratings yet

- Jamapsychiatry Lewis 2019 Oi 190089Document8 pagesJamapsychiatry Lewis 2019 Oi 190089Cristina PernasNo ratings yet

- Anxiety and Depression in COVID-19 Survivors - Role of Inflammatory and Clinical PredictorsDocument7 pagesAnxiety and Depression in COVID-19 Survivors - Role of Inflammatory and Clinical PredictorsDaniel A. SaldanaNo ratings yet

- Suicide Attempts in First-Episode Psychosis 2Document6 pagesSuicide Attempts in First-Episode Psychosis 2Adam García BuenoNo ratings yet

- Psychological Impact of COVID-19, Isolation, and QuarantineDocument9 pagesPsychological Impact of COVID-19, Isolation, and QuarantineIntan SariNo ratings yet

- Virtual Reality Study of Paranoid Thinking in TheDocument7 pagesVirtual Reality Study of Paranoid Thinking in TheAmiya SanthoshNo ratings yet

- 06 412 Amendola-1Document9 pages06 412 Amendola-1jackNo ratings yet

- Prolonged Psychosocial Effects of Disaster: A Study of Buffalo CreekFrom EverandProlonged Psychosocial Effects of Disaster: A Study of Buffalo CreekRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Sleep Quality Stress Level and COVID 19Document8 pagesSleep Quality Stress Level and COVID 19walkensiocsNo ratings yet

- Incidence of Depression Anxiety and SleeDocument10 pagesIncidence of Depression Anxiety and SleewalkensiocsNo ratings yet

- COVID 19 Pandemic Lifestyle Students MenDocument173 pagesCOVID 19 Pandemic Lifestyle Students MenwalkensiocsNo ratings yet

- Health Psychology and Behavioral MedicinDocument13 pagesHealth Psychology and Behavioral MedicinwalkensiocsNo ratings yet

- Mike Reinold Shoulder Clinical Exam ChecklistDocument20 pagesMike Reinold Shoulder Clinical Exam ChecklistAdmir100% (1)

- Adopt, Don't ShopDocument5 pagesAdopt, Don't ShopAlexis Vasquez-Morgan100% (3)

- Procter & Gamble Inc: ScopeDocument3 pagesProcter & Gamble Inc: Scopeacib177No ratings yet

- Jurnal Perineal Care Nisa PDFDocument11 pagesJurnal Perineal Care Nisa PDFNur Annisa FitriNo ratings yet

- Bayanihan To Recover As One (Bayanihan 2) BillDocument54 pagesBayanihan To Recover As One (Bayanihan 2) BillRappler100% (6)

- 10 Hour General Industry - Material Handling v.03.01.17 1 Created by OTIEC Outreach Resources WorkgroupDocument47 pages10 Hour General Industry - Material Handling v.03.01.17 1 Created by OTIEC Outreach Resources WorkgroupClint Baring ArranchadoNo ratings yet

- Common Surgical IncisionsDocument17 pagesCommon Surgical IncisionsShaika-Riza SakironNo ratings yet

- Bino - Lec - Midterm Exam - Yellow - PadDocument11 pagesBino - Lec - Midterm Exam - Yellow - PadDanielle SangalangNo ratings yet

- Housekeeping Manpower PlanDocument2 pagesHousekeeping Manpower PlanaajakirNo ratings yet

- Consolidated Ac. Party Buwan NG Wika EtcDocument8 pagesConsolidated Ac. Party Buwan NG Wika Etclara geronimoNo ratings yet

- PbisDocument36 pagesPbisapi-257903405No ratings yet

- List of Prohibited and Hazardous ChemicalDocument40 pagesList of Prohibited and Hazardous ChemicalKee SarakarnkosolNo ratings yet

- Effect of Vermicompost and Biofertilizers On Yield and Soil PDFDocument3 pagesEffect of Vermicompost and Biofertilizers On Yield and Soil PDFAgricultureASDNo ratings yet

- Models of Rehabilitation Component IA Role Name Affiliation: Swe/Swfd/Mr/M23 by Dr. P. Saleel KumarDocument13 pagesModels of Rehabilitation Component IA Role Name Affiliation: Swe/Swfd/Mr/M23 by Dr. P. Saleel KumarRainbowsNo ratings yet

- Soft Skills Are Abilities That Are Not Directly Related To A Specific Career, But ComplementDocument4 pagesSoft Skills Are Abilities That Are Not Directly Related To A Specific Career, But ComplementOscar ADSNo ratings yet

- Cestodes TableDocument5 pagesCestodes TableEiveren Mae SutillezaNo ratings yet

- Complete Guide To Endurance TrainingDocument282 pagesComplete Guide To Endurance TrainingLynseyNo ratings yet

- Maggi FinalDocument10 pagesMaggi FinalDeepak Singh NegiNo ratings yet

- Led Lighting in HospitalsDocument7 pagesLed Lighting in HospitalsNgọc Nguyễn ThảoNo ratings yet

- PIVOT 2016 Impact ReportDocument17 pagesPIVOT 2016 Impact ReportPivot100% (2)

- Serious Adverse Events Chapter 8: The Rebel GeniusDocument8 pagesSerious Adverse Events Chapter 8: The Rebel GeniusChelsea Green PublishingNo ratings yet

- Bologna Guidelines For Diagnosis and ManagementDocument20 pagesBologna Guidelines For Diagnosis and ManagementTony HardianNo ratings yet

- Counseling Psychology vs. Clinical PsychologyDocument3 pagesCounseling Psychology vs. Clinical PsychologyDivyaDeepthi18No ratings yet

- CHN-2-Module 1 - Study-GuideDocument3 pagesCHN-2-Module 1 - Study-GuideJHYANE KYLA TRILLESNo ratings yet

- PJ Nicholoff Steroid ProtocolDocument6 pagesPJ Nicholoff Steroid ProtocolYanna RizkiaNo ratings yet

- Innovative Lesson Plan.Document5 pagesInnovative Lesson Plan.MANOJNo ratings yet

- Orca Persuasive SpeechDocument2 pagesOrca Persuasive Speechapi-302199862No ratings yet

- Coat DiseaseDocument24 pagesCoat DiseaseRaissaNo ratings yet