Professional Documents

Culture Documents

General Practice

Uploaded by

wozenniubOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

General Practice

Uploaded by

wozenniubCopyright:

Available Formats

General practice

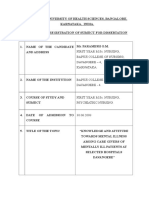

General practitioners’ knowledge of their patients’

psychosocial problems: multipractice questionnaire survey

Pål Gulbrandsen, Per Hjortdahl, Per Fugelli

Institute of General

Practice and

Abstract ies in Canada and Holland.4-7 Three of these studies,

Community

conducted among highly motivated general practition-

Objectives: To evaluate general practitioners’ ers or on selected patient groups, showed that general

Medicine,

PO Box 1130 knowledge of a range of psychosocial problems practitioners recognised 26% to 50% of their patients’

Blindern, N-0317 among their patients and to explore whether doctors’ psychosocial problems; one showed a recognition rate

Oslo, Norway

recognition of psychosocial problems depends on of 59%, but the design of the study had increased the

Pål Gulbrandsen,

research fellow previous general knowledge about the patient or the doctors’ attentiveness. That study found a positive cor-

Per Hjortdahl, type of problem or on certain characteristics of the relation between the duration of the doctor-patient

professor doctor or the patient. relationship and the level of the doctors’ awareness.5

Per Fugelli, Design: Multipractice survey of consecutive adult

professor From clinical experience we know that some problems

patients consulting general practitioners. Doctors and are readily communicated by the patients, while others

Correspondence to: patients answered written questions.

Dr Gulbrandsen. stay hidden. We do not know if the correlation

Setting: Buskerud county, Norway. described applies to problems of different natures. Pre-

BMJ 1997;314:1014–8 Subjects: 1401 adults attending 89 general vious studies have been too small to show if and how

practitioners during one regular working day in the accumulation of knowledge about different kinds

March 1995. of problems differs.

Main outcome measures: Doctors’ knowledge of nine Pattern recognition and the hypothetico-deductive

predefined psychosocial problems in patients; these process are the diagnostic strategies most frequently

problems were assessed by the patients as affecting used in clinical practice, and a possible pitfall of these

their health on the day of consultation; odds ratios for ways of reasoning is the entrapment by prior

the doctor’s recognition of each problem, adjusted for expectation.8 This could lead general practitioners to a

characteristics of patients, doctors, and practices; and selective awareness of psychosocial problems in

the doctor’s assessment of previous general patients in whom they expect to find such problems. If

knowledge about the patient. so, there is a potential for more vigilance in history tak-

Results: Doctors’ knowledge of the problems ranged ing, which in turn facilitates diagnosis and promotes

from 53% (108/203) of “stressful working conditions’ care.9 The possibility of selective awareness was not

to 19% (12/63) of a history of “violence or threats.” addressed in the studies mentioned above. General

Good previous knowledge of the patient increased the practitioners’ recognition of psychosocial problems

odds for the doctor’s recognition of “sorrow,” has to our knowledge not previously been studied in a

“violence or threats,” “substance misuse in close friend large, unselected population of adult patients.

or relative,” and “difficult conflict with close friend or The aim of our study was twofold: to evaluate gen-

relative.” Age and sex of doctor and patient, patient’s eral practitioners’ awareness of a range of predefined

educational level and living situation, and location of problems among adult patients in general practice and

practice influenced the doctor’s awareness. to explore whether doctors’ recognition depends on

Conclusions: Variation in the patients’ previous general knowledge about the patient, the type

communication abilities, the need for confidence in of problem, or characteristics of the patient and the

the doctor-patient relationship before revealing doctor.

intimate problems, and a tendency for the doctors to

be entrapped by their expectations may explain these

findings.

Subjects and methods

Using a questionnaire, we conducted a multipractice

survey in which general practitioners and their patients

Introduction answered mirrored questions. The study included

The importance of a lasting relationship between gen- patients 16 years of age or older attending the practices

eral practitioners and their patients is well during one regular working day. Patients in need of

documented.1 2 One aspect of such a relationship, con- urgent admission to hospital or unable to participate

sidered to be an essential part of general practice, is due to serious mental illness were excluded.

accumulated knowledge of the patients’ psychosocial The study was conducted in Buskerud county, Nor-

problems.3 This knowledge has been the focus of stud- way, after having been piloted in another part of the

1014 BMJ VOLUME 314 5 APRIL 1997

General practice

country. All 144 general practitioners in the county

were invited to join the study. Age, sex, being a special- Questions for patients and doctors

ist in general practice, and type of reimbursement were

determined for all general practitioners. We asked Questions mapping exposure to nine indicator

psychosocial problems, as experienced by patients.

about time spent in present practice, average number

Questions for doctors were mirrors of these:

of patients seen per day, and (using a method “Does/Is/Has this patient...”

developed by Grol et al10 ) the doctors’ feelings about • Have you ever been weighed down by sorrow?

working with patients with psychosocial problems or • Do you have a demanding caregiving task in your

psychosomatic symptoms. Eleven of the non- private life?

participant doctors did not supply this information. • Have you ever been subject to threats or violence

from someone you know very well?

Each practice was classified according to the defini-

• Is anyone that you feel close to subject to substance

tions of the classification committee of the World abuse?

Organisation of National Colleges, Academies, and • Are you having a difficult conflict with someone that

Academic Associations of General Practitioners/ you feel close to?

Family Physicians11 as solo or group practice and as • Do you usually feel lonely?

• Have you yourself been through family splitting?

being urban, suburban, or rural. Eighty nine doctors • Have you been unemployed for more than six

(62%) agreed to participate in the study. Heavy work months?

load (35) and planned study leave (7) were the reasons • Do you feel that your job is a strain, physically or

most often given for not participating. The participat- mentally?

ing doctors recorded all their consultations during a

regular work day chosen within two weeks in March

1995. had, they were asked to assess whether the problem

A total of 1407 patients were approached, of whom affected their health that day. Patients who answered

1401 were included (four did not want to participate “yes” to this question were considered to have a prob-

and two questionnaires were not adequately completed lem of possible clinical relevance. In the evaluation of

by the doctors). “unemployment” and “stressful working conditions,”

The questionnaire was not seen by the doctor until only patients aged 16-67 were included.

the end of the first consultation on the recording day. The percentage of problems present that was

At the end of each consultation the doctor handed known by the doctor was calculated for each of the

patients their copy of the questionnaire. Doctors com- nine problems. Whether the doctor knew of a problem

pleted their questionnaires after the last patient that or not was the dichotomous outcome variable used in

day, before leaving the surgery. Patients filled in their a logistic regression analysis performed for each prob-

copy at home and returned it directly to us. lem. Age and sex of the doctor and the patient, and

The questionnaires explored patients’ socio- previous knowledge dichotomised into scant (some,

demographic data, the main reason for the encounter, not at all) or good (very good, good) were included in

and the doctor’s assessment of his or her previous gen- the first step together with independent variables with

eral knowledge of the patient on a four point scale P values < 0.15 in the bivariate analyses. Interactions

(very good, good, some, not at all). between the main effect variables were tested.

The term “psychosocial problems” covers a wide The study was approved by the regional ethics

and ill defined set of situations and events. Among 15 committee for medical research.

studies found in the literature related to psychosocial

aspects of clinical work we identified more than 200

such problems ranging from children’s bedwetting to

Results

religious problems.4-7 12-22 We excluded psychological Non-participating doctors did not differ significantly

and existential problems (such as “nervousness” and from participating doctors. A total of 1217 (87%) of the

“religious problem”) as we wanted also the “social” 1401 patients returned their questionnaire, of whom

aspect to be present, leaving 114 relevant problems. It 64% were women. Judging by the doctors’ notes on the

was possible to classify 70% of these problems into patients, respondents were representative as to sex, liv-

three broad categories (problems related to bereave- ing situation, income level, educational level, and

ment, interpersonal problems, and problems related to source of income, but patients of middle age (40-59

work or finance), and another 20% could be classified years) replied more often (÷2 = 12.2, df = 2, P < 0.01)

as a combination of these three categories. The than younger or older patients. The most common

remaining problems were too diverse to be classified. reasons for encounter (as classified by the international

To map a range of psychosocial problems, we selected classification of primary care23) were hypertension,

nine indicator problems satisfying three conditions: all pregnancy, diabetes mellitus, back pain, and

three major categories should be represented; the depression—or, if grouped, symptoms and disorders of

problem should be common in general practice; and the musculoskeletal system, the cardiovascular system,

some of the indicators should readily be revealed and and the respiratory system; all were equally distributed

discussed by patients, others not. The pilot study between responders and non-responders. The doctors’

indicated that patients experienced an average of 2.2 previous general knowledge of the patients was lacking

problems, and that 1.1 problems affected their health or scant in 412 (34%) consultations and good in 797

on the day they were questioned; this showed that the (66%) consultations.

chosen indicators were commonly seen in general A total of 962 (79%) patients answered affirma-

practice. tively to at least one of the nine questions, and 422

The box lists the questions used to detect whether (34%) reported that at least one problem affected their

patients had any of the nine indicator problems. If they present health. The mean number of psychosocial

BMJ VOLUME 314 5 APRIL 1997 1015

General practice

Table 1 Prevalence of psychosocial problems assessed by patients as affecting their health on the day of consultation, according to

sex and age

No of No (%) of men No (%) of women

cases/No of % Of cases

Type of problem patients (95% CI) 16-39 40-59 >60 16-39 40-59 >60

Sorrow 168/1136 14.8 13/104 18/142 17/160 27/240 53/265 40/215

(12.7 to 16.9) (12.5) (12.7) (10.6) (10.8)* (20.0) (18.6)

Caregiving task 102/1134 9.0 9/105 18/144 6/167 28/247 30/265 11/206

(7.3 to 10.7) (8.6) (12.5) (3.6)* (11.3) (11.3) (5.3)*

Violence or threats 63/1171 5.4 6/107 7/148 5/177 16/252 25/270 4/217

(4.1 to 6.7) (5.6) (4.7) (2.8) (6.3) (9.3)* (1.8)**

Substance misuse in close 31/1176 2.6 4/104 3/149 2/178 8/254 12/268 2/223

friend or relative (1.7 to 3.6) (3.8) (2.0) (1.1) (3.1) (4.5) (0.9)

Difficult conflict 92/1170 7.9 10/107 12/146 8/176 24/253 33/266 5/222

(6.3 to 9.4) (9.3) (8.2) (4.5) (9.5) (12.4)** (2.3)***

Loneliness 85/1168 7.3 7/105 13/146 12/176 14/254 21/267 18/220

(5.8 to 8.8) (6.7) (8.9) (6.8) (5.5) (7.9) (8.2)

Family splitting 85/1170 7.3 9/107 13/149 8/174 18/256 31/267 6/217

(5.8 to 8.8) (8.4) (8.7) (4.6) (7.0) (11.6)** (2.8)**

Unemployment >6 months† 42/778 5.4 9/99 11/135 3/63 9/222 8/228 2/31

(3.8 to 7.0) (9.1) (8.1) (4.8) (4.1) (3.5) (6.5)

Stressful working conditions† 203/775 26.2 26/100 48/133 16/57 50/225 56/229 7/31

(23.1 to 29.3) (26.0) (36.1) (28.1) (22.2) (24.5) (22.6)

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ÷2 test of proportion of patients in this age group compared to proportion of patients in the other two age groups combined.

†Calculated for patients 16-67 years of age.

problems reported per patient was 1.9, or 0.7 if the patients who did not report this problem (data not

restricted to those perceived to affect health at the shown).

moment. Stressful working conditions and sorrow were Doctor’s variables except for sex and age group,

the most common psychosocial problems (table 1). and the practice variable “solo or group practice,” were

The only significant sex difference was the higher eliminated in the multivariate analyses (table 3. The

prevalence of stressful working conditions among general practitioner’s assessment of prior general

middle aged men (P = 0.03). knowledge of the patient correlated with knowledge of

A demanding caregiving task was significantly less sorrow, violence or threats, substance misuse in a close

common in older than younger men. Among women, a friend or relative, and a difficult conflict. The doctors’

demanding caregiving task, violence or threats, a diffi- recognition of sorrow, a demanding caregiving task,

cult conflict, and family splitting were significantly less and loneliness increased with the patient’s age. A

prevalent in the older age group, and sorrow less demanding caregiving task was less frequently

prevalent in the younger age group. Violence or recognised among male patients. Female and older

threats, a difficult conflict, and family splitting were doctors were more often aware of a patient’s difficult

more common in middle aged women. conflict. Among patients with less than 10 years of edu-

Doctors’ knowledge of the nine problems ranged cation, the doctors were more often aware of sorrow

from 53% (108/203) awareness of stressful working but less often aware of a difficult conflict. Violence or

conditions to 19% (12/63) for history of violence or threats were more often recognised among patients

threats (table 2). Violence or threats, a demanding car- who were the only adult in their household. Doctors in

egiving task, and loneliness were less frequently recog- rural practices were more often informed of their

nised than stressful working conditions. If patients did patients’ difficult conflicts or stressful working condi-

not indicate that they were affected by one of the nine tions than were their urban or suburban counterparts.

problems, or did not indicate that the problem affected

their health that day, the general practitioners noted

the presence of that problem among fewer than 10% Discussion

of the patients, except for stressful working conditions,

which the doctors stated were present among 22% of In Norway patients are free to change their general

practitioner, but in some rural areas the alternatives are

few. In 1987, 90% of the general practitioners claimed

Table 2 Doctor’s knowledge of psychosocial problems

they tried to maintain a personal list system.24

influencing patients’ health Buskerud county, which has 5.1% of the Norwegian

population and 4.9% of Norway’s area, has previously

No known/No of patients with

Type of problem problem (%; 95% CI)

been shown to be representative of the country as a

Sorrow 64/168 (38.1; 30.8 to 45.4) whole.25 The representativeness of our study is

Caregiving task 25/102 (24.5; 16.2 to 32.8) supported by three measures: participant and non-

Violence or threats 12/63 (19.0; 9.3 to 28.7) participant doctors did not differ significantly as to

Substance abuse in close friend or relative 14/31 (45.2; 27.7 to 62.7) their feelings towards working with psychosocial prob-

Difficult conflict 43/92 (46.7; 36.5 to 56.9) lems; the patients’ reasons for consultation were similar

Loneliness 26/85 (30.6; 20.8 to 40.4) to the ones reported in earlier large Norwegian surveys

Family splitting 41/85 (48.2; 37.6 to 58.8) of general practice24; and the doctors’ assessment of

Unemployment >6 months 20/42 (47.6; 32.5 to 62.7) previous knowledge of their patients was similar to that

Stressful working conditions 108/203 (53.2; 46.3 to 60.1) reported in Hjortdahl’s national study.2

1016 BMJ VOLUME 314 5 APRIL 1997

General practice

Discussing psychosocial problems

Table 3 Odds ratios for doctors’ knowledge of indicator psychosocial problems.*

The importance of assessing the patient’s own evalua- Independent variables not listed were eliminated in regression analyses

tions has been widely recognised,26 but it could be

Variable No of patients Odds ratio (95% CI) P value

argued that the psychosocial problems we have used in

Sorrow (n=167†; 63 known to doctor, 104 not known to doctor)

this study need not be relevant to the patient’s reason

Age of patient (years):

for the current consultation. We tried to ensure clinical

<40 years 40 1.0

relevance by restricting analysis to the problems that 40-59 years 71 3.66 (1.25 to 10.7) 0.18

patients assessed as affecting their present health. >60 years 56 6.35 (2.06 to 19.6) 0.001

Patients could avoid discussing such problems because Patient’s educational level:

they do not expect the doctor to be able to help them, Schooling <10 years 66 1.0

because they fear being invaded by emotionally Schooling>10 years 101 0.44 (0.21 to 0.91) 0.028

disturbing questions, or because they are already Previous knowledge:

reconciled with their situation. Even so, awareness of Scant 37 1.0

such a problem could sometimes explain symptoms to Good 130 2.83 (1.12 to 7.17) 0.028

the doctor and prevent unnecessary diagnostic Caregiving task (n=102; 25 known to doctor, 77 not known to doctor)

procedures.2 Age of patient:

Patients’ reluctance to reveal intimate information <40 years 37 1.0

40-59 years 48 2.04 (0.66 to 6.24) 0.214

could explain the findings that only a fifth to a half of

>60 years 17 4.39 (1.13 to 17.0) 0.032

the psychosocial problems perceived by the patients as

Sex of patient:

affecting their health that day were recognised by the

Male 33 1.0

general practitioners, and that awareness depends on Female 69 3.70 (1.12 to 12.3) 0.033

the type of problem present. This could reflect a Violence or threats (n=63; 12 known to doctor, 51 not known to doctor)

deficiency in the doctor-patient relationships of many Living situation:

general practitioners, as proposed by Yaffe,6 or it could Other adult in household 44 1.0

show that knowledge of psychosocial problems is not No other adult in household 19 8.67 (2.07 to 36.3) 0.003

as important in general practice as is claimed by lead- Previous knowledge:

ing proponents.3 The doctors’ awareness of psycho- Scant 14 1.0

social problems was lower in our study than that Good 49 5.50 (0.57 to 53.1) 0.140

reported by Rosenberg and Pless, whose study design Substance misuse in close friend or relative (n=31; 14 known to doctor, 17 not known to doctor)

could have increased the participants’ vigilance.5 The Previous knowledge:

Scant 7 1.0

study of Yaffe et al, performed on middle aged patients,

Good 24 7.09 (0.74 to 68.2) 0.143

found an overall awareness of 26% of the known

Difficult conflict (n=92; 43 known to doctor, 49 not known to doctor)

psychosocial problems.6

Sex of patient:

The question concerning violence or threats was

Male 30 1.0

phrased so as to include possible experiences from Female 62 3.06 (0.99 to 9.44) 0.052

childhood or in relation to friends as well as conjugal Sex of doctor:

violence; it showed no significant sex differences in Male 67 1.0

prevalence. The low prevalence in comparison to other Female 25 3.25 (1.01 to 10.4) 0.048

studies27 28 is largely explained by the fact that only 39% Age of doctor:

of those with experience of violence or threats said that <45 years 59 1.0

it affected their health on the day of consultation. The >45 years 33 3.19 (1.09 to 9.38) 0.035

result indicates that although conjugal violence mainly Patient’s educational level:

affects women,29 the proportion of men affected is not Schooling <10 years 30 1.0

negligible. Schooling >10 years 62 4.12 (1.36 to 12.5) 0.012

Location of practice:

Urban or suburban 67 1.0

Previous knowledge of the patient

Rural 25 6.13 (1.88 to 20.0) 0.003

The impact of previous general knowledge of the

Previous knowledge:

patient was different for different kinds of problems. Scant 18 1.0

For some of the problems the odds ratios were large, Good 74 3.39 (0.88 to 13.1) 0.076

although not always significant at the 5% level. As these Loneliness (n=85; 26 known to doctor, 59 not known to doctor)

correlations support clinical experience, it would be Age of patient:

wrong to dismiss them. <40 years 21 1.0

The doctors’ awareness of work related problems 40-59 years 34 1.64 (0.36 to 7.35) 0.520

and family splitting was not directly related to prior >60 years 30 5.16 (1.20 to 22.3) 0.028

general knowledge, probably because this information Living situation:

is exchanged early in the doctor-patient relationship. Other adult in household 55 1.0

Carrying sorrow, being in a difficult conflict with a close No other adult in household 30 2.65 (0.92 to 7.66) 0.072

person, or substance misuse in a close friend or relative Family splitting (n=84†; 41 known to doctor, 43 not known to doctor)

Living situation:

are situations which require trust in the confidant, and

Other adult in household 44 1.0

accordingly previous general knowledge would have

No other adult in household 40 2.38 (0.99 to 5.72) 0.052

an effect. This effect and a relatively high level of recog-

Stressful working conditions (n=203; 108 known to doctor, 95 not known to doctor)

nition suggest that this information reaches the doctor Location of practice:

by diffusion over the years. A victim of violence or Urban or suburban 164 1.0

threats also relies on trust to confide, but the doctors’ Rural 39 2.30 (1.09 to 4.86) 0.028

recognition was low. Sugg and Inui have found that *No significant independent variables for knowledge of unemployment (n=42; knowledge 20, no knowledge 22)

family physicians avoid the subject of violence because †One case missing due to missing value in one variable.

BMJ VOLUME 314 5 APRIL 1997 1017

General practice

Funding: Quality Assurance Program of the Norwegian

Key messages Medical Association.

Conflict of interest: None.

x At least one third of patients in general practice

have psychosocial problems that they perceive

1 Hjortdahl P, Borchgrevink CF. Continuity of care: influence of general

as influencing their present health practitioners’ knowledge about their patients on use of resources in con-

sultations. BMJ 1991;303:1181-4.

x General practitioners recognise a fifth to a half 2 Leopold N, Cooper J, Clancy C. Sustained partnership in primary care. J

of these problems, depending on the type of Famy Pract 1996;42:129-37.

3 McWhinney IR. The principles of family medicine. In: A textbook of family

problem, previous general knowledge of the medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989:12-26.

patient, and sociodemographic characteristics of 4 Stewart MA, Buck CW. Physicians’ knowledge of and response to patients’

problems. Medical Care 1977;15:578-85.

the patient 5 Rosenberg EE, Pless IB. Clinicians’ knowledge about the families of their

x Variation in the patients’ wishes and abilities to patients. Family Practice 1985;2:23-9.

6 Yaffe MJ, Stewart MA. Factors influencing doctors’ awareness of the life

communicate, the need for confidence in the problems of middle-aged patients. Medical Care 1985;23:1276-82.

doctor-patient relationship before revealing 7 Querido A. The family physician. Direct evaluation of the work of some

general practitioners. In: The efficiency of medical care. A critical discussion of

intimate problems, and a tendency for doctors measuring procedures. Leiden: Stenfert Kroese, 1963:46-52.

to be entrapped by their expectations may be 8 Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Guyatt GH, Tugwell P. The clinical examination.

In: Clinical epidemiology. A basic science for clinical medicine. Boston: Little,

some reasons for these findings Brown, 1991:19-50.

9 Barbour A. Diagnostic strategies for unrecognized personal illness. In:

Caring for patients. A critique of the medical model. Stanford: Stanford

University Press, 1995:81-95.

they are afraid of getting flooded by multiple other 10 Grol R, Mokkink H, Smits A, van Eijk J, Beek M, Mesker P, et al. Work sat-

isfaction of general practitioners and the quality of patient care. Family

problems.30 Since the doctors seem to be aware of this Practice 1985;2:128-35.

problem more often in patients who live alone, it is 11 WONCA Classification Committee. An international glossary for

primary care. Family Practice 1981;13:671-81.

possible that it takes a major life event, such as a sepa- 12 Schmeling-Kludas C, Odensass C. [Psychosomatic medicine in the

ration or divorce, for such information to be general hospital: problem spectrum in a random sample of 100 internal

medicine patients.] Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie

communicated. 1994;44:372-81. (In German.)

In contrast to Yaffe et al,6 we found that doctors’ 13 Martin FJ, Bass MJ. The impact of discussion of non-medical problems in

the physician’s office. Family Practice 1989;6:254-8.

recognition of problems was strongly and significantly 14 Schwenk TL, Clark CH, Jones GR, Simmons RC, Coleman ML. Defining

affected by the patient’s sociodemographic characteris- a behavioral science curriculum for family physicians: what do patients

think? J Fam Pract 1982;15:339-45.

tics, such as age, sex, educational level, or living alone. 15 Kushner K, Meyer D, Hansen M, Bobula J, Hansen J, Pridham K. The

This suggests that selective awareness was present family conference: what do patients want? J Fam Pract 1986;23:463-7.

16 Jones I, Morrell D. General practitioners’ background knowledge of their

among the doctors. Expecting that patients had a patients. Family Practice 1995;12:49-53.

demanding caregiving task or were lonely could have 17 Goldberg RJ, Novack DH. The psychosocial review of systems. Soc Sci Med

1992;35:261-9.

affected the doctors to such a degree that previous 18 Eide R, Thyholdt R, Hamre E. Relationship of psychosocial factors to

general knowledge was unimportant, an example of bodily and psychological complaints in a population in western Norway.

the pitfall described by Sackett et al.8 Another possible Psychother Psychosomat 1982;37:218-34.

19 Miller PM, Salter DP. Is there a short-cut? An investigation into the life

explanation is that it is not the expectations that help event interview. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1984;70:417-27.

the doctors come to a decision, but opinions on which 20 Chen CY, Liang YI, Hsieh WC. Evaluation of clinical diagnosis and

stressful life events in patients at a rural family practice centre. Family

patients need their advice. The effects of the patients’ Practice 1989;6:259-62.

characteristics may be due to the patients’ ability to 21 Leeflang RL, Klein-Hesselink DJ, Spruit IP. Health effects of

unemployment—II. Men and women. Soc Sci Med 1992;34:351-63.

communicate: doctors were more aware of sorrow 22 Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. J Psychosomat

among those patients with little education and more Res 1967;11:213-8.

23 Lamberts H, Wood M. International classification of primary care: tabu-

aware of difficult conflicts among those patients at lar list. In: International classification of primary care. Oxford: Oxford

higher educational levels. University Press, 1989:68-102.

24 Hjortdahl P. Continuity of care in general practice. A study related to ideo-

logy and reality of continuity of care in Norwegian general practice [dis-

Conclusions sertation]. Oslo: University of Oslo, 1992.

25 Tellnes G. Sickness certification—an epidemiological study related to

Psychosocial problems which patients consider to be community medicine and general practice [dissertation]. Oslo: University

affecting their health are abundant in general practice. of Oslo, 1990.

26 Pendleton D, Schofield T, Tate P, Havelock P. General approaches to the

Doctors’ recognition of such problems depends consultation. In: The consultation. An approach to learning and teaching.

primarily on type of problem, previous general knowl- Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984:1-22.

27 Ogg J, Bennett G. Elder abuse in Britain. BMJ 1992;305:998-9.

edge of the patient, and sociodemographic characteris- 28 McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, Dill L, Schroeder AF, DeChant HK, et

tics of the patient. Variation in the patients’ wishes and al. The “battering syndrome”: prevalence and clinical characteristics of

domestic violence in primary care internal medicine practices. Ann Intern

ability to communicate, the need for confidence in the Med 1995;123:737-46.

doctor-patient relationship before revealing intimate 29 Smilkstein G, Aspy CB, Quiggins PA. Conjugal conflict and violence: a

review and theoretical paradigm. Family Medicine 1994;26:111-6.

problems, and a tendency for the doctors to be 30 Sugg NK, Inui T. Primary care physicians’ response to domestic violence:

entrapped by their expectations are some likely opening Pandora’s box. JAMA 1992;267:3157-60.

reasons for these findings. (Accepted 17 February 1997)

1018 BMJ VOLUME 314 5 APRIL 1997

You might also like

- A Qualitative StudyDocument6 pagesA Qualitative StudyPaula CelsieNo ratings yet

- Good For QualitativeDocument9 pagesGood For QualitativeWassie TsehayNo ratings yet

- PDF on effects of community occupational therapyDocument22 pagesPDF on effects of community occupational therapyalwanNo ratings yet

- Developing A Psychiatrist - Patient Relationship When Both People Are Doctors: A Qualitative StudyDocument10 pagesDeveloping A Psychiatrist - Patient Relationship When Both People Are Doctors: A Qualitative Studymasyi wimy johandhikaNo ratings yet

- My ProjectDocument34 pagesMy ProjectrahmatullahqueenmercyNo ratings yet

- Finding the Path in Alzheimer’s Disease: Early Diagnosis to Ongoing Collaborative CareFrom EverandFinding the Path in Alzheimer’s Disease: Early Diagnosis to Ongoing Collaborative CareNo ratings yet

- Community OT for dementia patients and caregiversDocument4 pagesCommunity OT for dementia patients and caregiversRafael MezaNo ratings yet

- Mia Does A-Level Psychology NotesDocument5 pagesMia Does A-Level Psychology NotesVanessaNo ratings yet

- The Difficult Patient' As Perceived by Family Physicians: Dov Steinmetz and Hava TabenkinDocument6 pagesThe Difficult Patient' As Perceived by Family Physicians: Dov Steinmetz and Hava TabenkinRomulo Vincent PerezNo ratings yet

- First Year M.Sc. Nursing, Bapuji College of Nursing, Davangere - 4, KarnatakaDocument14 pagesFirst Year M.Sc. Nursing, Bapuji College of Nursing, Davangere - 4, KarnatakaAbirajanNo ratings yet

- Article For Journal 2Document5 pagesArticle For Journal 2awuahbohNo ratings yet

- Neuropsychological Assessment PrinciplesDocument8 pagesNeuropsychological Assessment Principlesnellianeth orozco garciaNo ratings yet

- DTSCH Arztebl Int, 2021Document15 pagesDTSCH Arztebl Int, 2021Nabiel AnwarNo ratings yet

- HSR 2179Document13 pagesHSR 2179Lisa SariNo ratings yet

- 2017 Embracing Uncertainty To Advance Diagnosis inDocument2 pages2017 Embracing Uncertainty To Advance Diagnosis inpainfree888No ratings yet

- Heidi 467Document3 pagesHeidi 467Medicina UFU 92No ratings yet

- Bmjopen 2014 006578Document18 pagesBmjopen 2014 006578Ortopedia HGMNo ratings yet

- (I) Chapter 1Document11 pages(I) Chapter 1Kim Paulo Nielo BartolomeNo ratings yet

- Timlim 2014Document14 pagesTimlim 2014Romina Fernanda Inostroza NaranjoNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Withholding The Truth From Dying PatientsDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Withholding The Truth From Dying PatientsTEHKHUM SULTANALINo ratings yet

- Clinical Reasoning: Linking Theory To Practice and Practice To TheoryDocument14 pagesClinical Reasoning: Linking Theory To Practice and Practice To Theorylumac1087831No ratings yet

- Restraint in NursingDocument6 pagesRestraint in Nursingbabayao35No ratings yet

- Benefits of Cognitive-Motor Intervention in MCI and Mild To Moderate Alzheimer DiseaseDocument6 pagesBenefits of Cognitive-Motor Intervention in MCI and Mild To Moderate Alzheimer DiseaseLaura Alvarez AbenzaNo ratings yet

- 2012 Article 2129Document9 pages2012 Article 2129RodrigoSachiFreitasNo ratings yet

- A 7 Minute Neurocognitive Screening Battery Highly Sensitive To Alzheimer's DiseaseDocument7 pagesA 7 Minute Neurocognitive Screening Battery Highly Sensitive To Alzheimer's DiseaseRealidades InfinitasNo ratings yet

- Cope StudyDocument9 pagesCope StudyCarmen Paz Oyarzun ReyesNo ratings yet

- Mejora de Validez en Investig Del Tratamiento de ComorbilidadDocument11 pagesMejora de Validez en Investig Del Tratamiento de ComorbilidadDanitza YhovannaNo ratings yet

- Jama DualdxDocument6 pagesJama DualdxGise QuinteroNo ratings yet

- Categorizing Patients in A Forced-Choice Triad Task: The Integration of Context in Patient ManagementDocument8 pagesCategorizing Patients in A Forced-Choice Triad Task: The Integration of Context in Patient ManagementFrontiersNo ratings yet

- 1354 FullDocument4 pages1354 FullDaniel ChristoNo ratings yet

- DBT in ASDDocument9 pagesDBT in ASDCarregan AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Adherencia Al Tratamiento de Crisis Funcionales DisociativasDocument7 pagesAdherencia Al Tratamiento de Crisis Funcionales DisociativasluciaNo ratings yet

- Compliance With Hand Therapy Programs - Therapist and Patients PerceptionsDocument10 pagesCompliance With Hand Therapy Programs - Therapist and Patients PerceptionssammyrasaNo ratings yet

- ndt-18-891Document7 pagesndt-18-891Julio DelgadoNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Motivational Interviewing On Medication Adherence and Hospitalization Rates in Nonadherent Patients With Multi-Episode SchizophreniaDocument10 pagesThe Effect of Motivational Interviewing On Medication Adherence and Hospitalization Rates in Nonadherent Patients With Multi-Episode SchizophreniaCarmen IoanaNo ratings yet

- Consensus On Gut FeelingsDocument6 pagesConsensus On Gut FeelingsJoana MoreiraNo ratings yet

- The Overdiagnosis of Depression in Non-Depressed Patients in Primary CareDocument7 pagesThe Overdiagnosis of Depression in Non-Depressed Patients in Primary Careengr.alinaqvi40No ratings yet

- UGML JAMA - I - How To Get StartedDocument3 pagesUGML JAMA - I - How To Get StartedAlicia WellmannNo ratings yet

- Delirium 29Document5 pagesDelirium 29BLANCA TATIANA PONCIANO MERINONo ratings yet

- Patient Practitioner Relationship 1Document24 pagesPatient Practitioner Relationship 1Dr Aniqa SundasNo ratings yet

- Boa Comunicação (BMJ02) PDFDocument4 pagesBoa Comunicação (BMJ02) PDFJonas NascimentoNo ratings yet

- Decision Making in General PracticeDocument3 pagesDecision Making in General Practiceأحمد خيري التميميNo ratings yet

- Carlsen Et Al-2006-Health ExpectationsDocument10 pagesCarlsen Et Al-2006-Health ExpectationsRufus Michael-AinaNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Article Critique Epsy5050Document10 pagesQualitative Article Critique Epsy5050api-427277840No ratings yet

- Problem Identification and ClarificationDocument19 pagesProblem Identification and ClarificationchristinemfranciaNo ratings yet

- Person-Centred Communication in Healthcare for Older PeopleDocument9 pagesPerson-Centred Communication in Healthcare for Older Peoplegladeva yugi antariNo ratings yet

- 2007 Graff EffectofcommunityoccupationaltherqualitylifemoodhealthstatusDocument9 pages2007 Graff EffectofcommunityoccupationaltherqualitylifemoodhealthstatusSamantha ColleNo ratings yet

- 211.full Two Words To Improve Physician-Patient Communication What ElseDocument4 pages211.full Two Words To Improve Physician-Patient Communication What ElsepassionexcellenceNo ratings yet

- Cancer Pain Management Program: Patients' Experiences - A Qualitative StudyDocument12 pagesCancer Pain Management Program: Patients' Experiences - A Qualitative StudyKEANNA ZURRIAGANo ratings yet

- A Clinical Pathway To Standardize Care of Children With Delirium in Pediatric Inpatient Settings-2019Document10 pagesA Clinical Pathway To Standardize Care of Children With Delirium in Pediatric Inpatient Settings-2019Juan ParedesNo ratings yet

- Interventions To Enhance Communication Among Patients, Providers, and FamiliesDocument8 pagesInterventions To Enhance Communication Among Patients, Providers, and FamiliesvabcunhaNo ratings yet

- How Physicians Manage Medical Uncertainty: A Qualitative Study and Conceptual TaxonomyDocument17 pagesHow Physicians Manage Medical Uncertainty: A Qualitative Study and Conceptual TaxonomyAlexNo ratings yet

- PRELIMS - NCMA216 TRANS - Nursing Process in PharmacologyDocument2 pagesPRELIMS - NCMA216 TRANS - Nursing Process in Pharmacologybnancajas7602valNo ratings yet

- Gangguan BipolarDocument8 pagesGangguan BipolarjulianasanjayaNo ratings yet

- Psychoeducation: 19 July 2018 Unit VI Topic DiscussionDocument26 pagesPsychoeducation: 19 July 2018 Unit VI Topic DiscussionDana Franklin100% (1)

- Clinical Nursing JudgementDocument5 pagesClinical Nursing Judgementapi-546503916No ratings yet

- C Langeland, E., Riise, T., Hanestad, B. R., Nortvedt, M. W., Kristoffersen, K., & Wahl, A. K. (2006) .Document8 pagesC Langeland, E., Riise, T., Hanestad, B. R., Nortvedt, M. W., Kristoffersen, K., & Wahl, A. K. (2006) .Ign EcheverríaNo ratings yet

- Research Purpose, Problem StatementsDocument4 pagesResearch Purpose, Problem StatementsManish Kohli100% (1)

- Comunica Ting With PsychoticsDocument3 pagesComunica Ting With PsychoticsC. B.No ratings yet

- ME - Ethical Decision Making On Truth Telling in Terminal Cancer - Medical Students' Choices Between Patient Autonomy and Family PaternalismDocument9 pagesME - Ethical Decision Making On Truth Telling in Terminal Cancer - Medical Students' Choices Between Patient Autonomy and Family PaternalismAya SalahNo ratings yet

- 2024 Tariff TablesDocument1,444 pages2024 Tariff TablesBlessingNo ratings yet

- Sample - 1 Mat QuestionDocument13 pagesSample - 1 Mat QuestionwozenniubNo ratings yet

- Reliability Measuring Internal ConsistenDocument2 pagesReliability Measuring Internal ConsistenwozenniubNo ratings yet

- Three Principles of Pragmatism For Research On Organizational ProcessesDocument10 pagesThree Principles of Pragmatism For Research On Organizational ProcessesMuhammad zahirNo ratings yet

- TWDocument16 pagesTWDrago DragicNo ratings yet

- Seismic Vulnerability of Structures in Sikkim During 2011 EarthquakeDocument20 pagesSeismic Vulnerability of Structures in Sikkim During 2011 EarthquakeManpreet SinghNo ratings yet

- The Climate of War Violence Warfare and Climatic Reductionism - David N LivingstoneDocument8 pagesThe Climate of War Violence Warfare and Climatic Reductionism - David N LivingstoneMadisson CarmonaNo ratings yet

- Annex 7 Workshop at Eastern Partnership Youth ForumDocument4 pagesAnnex 7 Workshop at Eastern Partnership Youth ForumGUEGANNo ratings yet

- Real property dispute over notice of levy annotation (37Document15 pagesReal property dispute over notice of levy annotation (37heyoooNo ratings yet

- Chapter Five - Globalization of Irish Step DanceDocument38 pagesChapter Five - Globalization of Irish Step DanceElizabeth Venable0% (1)

- Former Ohio Wildlife Officer Convicted of Trafficking in White-Tailed DeerDocument2 pagesFormer Ohio Wildlife Officer Convicted of Trafficking in White-Tailed DeerThe News-HeraldNo ratings yet

- EAD 513 Kirk Summers Cultural Functions in PracticeDocument6 pagesEAD 513 Kirk Summers Cultural Functions in PracticeKirk Summers100% (1)

- PNR V BruntyDocument21 pagesPNR V BruntyyousirneighmNo ratings yet

- Croatian Films of 2006 ExploredDocument80 pagesCroatian Films of 2006 ExploredCoockiNo ratings yet

- Heirs vs Garilao (2009) Land Retention RightsDocument2 pagesHeirs vs Garilao (2009) Land Retention RightsTrek AlojadoNo ratings yet

- Bhanu ResumeDocument7 pagesBhanu ResumeOrugantirajaNo ratings yet

- Free Tuition Fee Application Form: University of Rizal SystemDocument2 pagesFree Tuition Fee Application Form: University of Rizal SystemCes ReyesNo ratings yet

- Micro and Macro Environment of NestleDocument2 pagesMicro and Macro Environment of Nestlewaheedahmedarain56% (18)

- The Thief of AmsterdamDocument2 pagesThe Thief of AmsterdamBlagitsa Arizanova ShopovNo ratings yet

- Sara's CAS Proposal FormDocument3 pagesSara's CAS Proposal FormsaraNo ratings yet

- Soriano Et Al., v. CIR Facts: The Case Involved Consolidated Petitions For Certiorari, ProhibitionDocument4 pagesSoriano Et Al., v. CIR Facts: The Case Involved Consolidated Petitions For Certiorari, ProhibitionLouise Bolivar DadivasNo ratings yet

- Re-appropriation of Rs. 3.99 lakh for publicationsDocument1 pageRe-appropriation of Rs. 3.99 lakh for publicationsAshish Singh Negi100% (1)

- Bharat MalaDocument29 pagesBharat MalaNavin GoyalNo ratings yet

- VMF Error LogDocument11 pagesVMF Error LogTest PhaseNo ratings yet

- Name: Yeison Adrián Vargas Suaza Grade: 11°A: Realización de Ejercicios PropuestosDocument4 pagesName: Yeison Adrián Vargas Suaza Grade: 11°A: Realización de Ejercicios Propuestosyeison adrian vargasNo ratings yet

- NAME: - Grade Level: 12 Q:2 - Lesson: 1Document2 pagesNAME: - Grade Level: 12 Q:2 - Lesson: 1neschee leeNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument22 pagesUntitledArjun kumar ShresthaNo ratings yet

- Ch1. Considering Materiality and RiskDocument47 pagesCh1. Considering Materiality and RiskAli AlbaqshiNo ratings yet

- Strong WindDocument3 pagesStrong WindYuli IndrawatiNo ratings yet

- The Warrior KingDocument4 pagesThe Warrior Kingapi-478277457No ratings yet

- NEw IC 38 SummaryDocument80 pagesNEw IC 38 SummaryMadhup tarsolia100% (2)

- HRD Lecture No 1,2-EXTN-507-Dr.G.K.SasaneDocument27 pagesHRD Lecture No 1,2-EXTN-507-Dr.G.K.SasaneAgril. Extension DepartmentNo ratings yet

- Essay On The Food Security in IndiaDocument8 pagesEssay On The Food Security in IndiaDojo DavisNo ratings yet

- KLTG23: Dec - Mac 2015Document113 pagesKLTG23: Dec - Mac 2015Abdul Rahim Mohd AkirNo ratings yet