Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Epic Conventions

Uploaded by

dakshitarai11Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Epic Conventions

Uploaded by

dakshitarai11Copyright:

Available Formats

EPIC CONVENTIONS

Color Theme- Dakshita | Dechen | Cherring

INTRODUCTION- DAKSHITA

Good Morning Everyone. I hope you all had a fun time with your families in

the past holidays. As we resume with the discussions and presentations

concerning our texts once again, me (Dakshita), Dechen, and Chhering are

present before you today with a presentation on the text of the

Mahabharata, concerning its structural and conceptual feautures.

By the end of the presentation we hope to have provided an overview on the

overall narratology, themes, conventions, and specifications of the text. It is

not as plain as it sounds though. If you pay attention, by the end you will

realise the sheer complexity yet beauty of the text and why it is a

foundational block in the literary culture and tradition of India.

I request Cherring to take over now.

GENERAL DEFINING FEATURES OF INDIAN EPICS- CHHERING

Good morning everyone. I will start now with a very foundational yet

important topic of today’s presentation, and that is about what defines the

Indian Epics. What are their defining features?

Firstly, Indian Epics are narrative in nature- which means they

Tell a story in song, poetry, rhythmic prose, and also with perhaps some

unsung parts.

Secondly, they are poetic, meaning they are formulaic and mostly have an

ornamental style.

Thirdly, they are heroic- much like what we have studied about the Greek

Epics and Tragedies- they tell adventures of extraordinary people.

However, there can be thematic and character based variations.

Either it showcases martial and human blends with the magical and celestial,

with no clear division between the two realms, and hero or heroines often

deified after death, crossing from human to divine.

Or that,

Epic hero or heroines are not necessarily models or exemplary ideals for

human behavior, which means, their actions may not offer practical advice or

assistance to the rest of us in living our everyday lives.

Fourthly, the feature that gets highlighted is the intermingling of deities and

humankind. Gods mix in human affairs for their own and the cosmos’

benefit. Epics attribute social and moral problems of humankind to the will of

the gods, such as- Gods make humans sin, die, and expose humans to

conflicts, and that humans cannot escape their fate, or that human suffering

is inevitable and life is sometimes ruthless in nature.

I think a majority of you will agree that these concepts have also endured the

ravages of time and continue to be a part or layman psychological processes

even today.

I will request Dechen to elaborate on the next topic now.

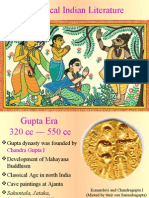

THREE EPIC TYPES IN INDIAN LITERARY CULTURE- DECHEN

The major Indian epic types are - Marital, Sacrificial, and Romantic.

Indian epics encompass a rich tapestry of themes, prominently featuring

three major epic types: Marital, Sacrificial, and Romantic. Marital epics, such

as the Ramayana, delve into the complexities of duty, loyalty, and familial

bonds.

Sacrificial epics, exemplified by the Mahabharata, explore the consequences

of power struggles and ethical dilemmas, often revolving around a grand

conflict. Romantic epics, like the stories of Radha and Krishna, weave tales of

divine love, passion, and spiritual devotion. Together, these epic types

showcase the diversity of Indian storytelling, reflecting the cultural,

philosophical, and moral nuances embedded in the country's ancient

narratives.

FUNCTIONS OF EPIC PERFORMANCES- CHHERING

An interesting aspect of Indian storytelling is that it tends to be majorly

performative in nature. Why is this performative aspect necessary though?

What are its functions?

Epics and their ceremonial performaces act as a means for protection and

documentation for the ritual beliefs of the people. It tells the story of a

community or culture, and helps in the continuity of the tradition and self-

identity of a culture.

The Mahabharata for example, has repeatedly acted as a social sample of the

bygone ages for modern day sociologists even though its origins and

differentiations of truth and myth are hugely debated. It is also a source of

great sentiment and pride in tradition of multitudes of communities of the

country and beyond.

COMMON EPIC THEMES AND TEACHINGS- CHHERING

Now, onto the common themes and teachings followed by Sanskrit and folk

epics.

Firstly there is-

Dharma, the cosmic law of righteousness, the moral law, and one’s ethical

duty:

The Mahabharata may be considered a “great treatise on dharma”, and its

epic heroes’ stories drive home the teachings of dharma. Note well, however,

that the teachings of dharma are subtle and not easy to define in specific epic

texts.

Then comes the theme of-

Fatalism: fate, or daiva, expresses the will of the gods and will be done. The

gods’ cosmic interests are often in conflict with those of humans: fate, in

Indian epics is a strong, oppressive force which manifests itself in

unpredictable ways and places the central characters in difficult positions.

And thirdly:

The Doctrine of divine grace and the way of bhakti (devotion or love) to final

release (or moksha): The Mahabharata may also be considered to teach these

cosmic precepts. Krishna is omnipresent as the divine manifestation in the

midst of human conflicts, and the epic’s heroes are Krishna’s most ardent

devotees.

A great example many of you might remember is, if you are familiar with the

Mahabharata, that Arjuna was clouded with hesitation and moral conflict

before the great battle, since it was his own kinfolk that he was supposed to

kill. In the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna is the one to dispel these doubts of him.

In this way, Krishna allows Arjuna tounderstand the necessity of killing his

kinsmen in the cosmic context. Krishna’s grace teaches bhakti (love, devotion)

as the means to liberation from the wheel of death and rebirth (samsara),

reconnecting to the theme we just dicussed.

STRUCTURE OF THE MAHABHARATA- DAKSHITA

According to multiple sources, the Mahabharata is the longest story ever

written and it was composed in a form that was a mixture of prose and

poetry.

Originally, this tale was composed of around 8000 shlokas. Gradually, it

reached the form in which it is known today- a massive narrative of around

1,00,000 shlokas. Undoubtedly, the composition has to have happened in

layers and chapters. So here I will throw some light on the 18 Parvas or

chapters of the story. You can try to guess the chapter contents in your minds

by the names-

1. Adi Parva – Sets up the story describing the origin of the core stories

roughly till the Indraprastha story.

2. Sabha Parva - This chapter recounts the story of dice game leading to

eventual exile of the Pandavas.

3. Vana Parva - This chapter provides the detail of the twelve years spent

in exile by the Pandavas. (vanaprastha)

4. Virata Parva - This chapter describes the last year of incognito.

5. Udyoga Parva - This chapter contains the stories of preparations,

consultations and negotiations for the war.

6. Bhishma Parva - This chapter describes the first ten days of war when

Bhishma was the chief commander of the Kaurava forces. It also

includes the Bhagavad Gita.

7. Drona Parva - The next five days of the war are recounted with Drona

as the chief commander of the Kaurava forces.

8. Karna Parva - The next two days of the war are described with Karna

as the chief commander of the Kaurava forces.

9. Shalya Parva -This chapter describes the last day of the war when

Shalya is the chief commander of the Kaurava forces.

10.Sauptika Parva - The incidents which happen at the night of the

eighteenth day are recounted.

11.Stree Parva - This chapter includes the lamentation of the widows after

the battle.

12.Shanti Parva - Bhishma, lying on the bed of arrows, gives a long

discourse on various Yudhishthira about various subjects. This is the

longest chapter of the Mahabharata.

13.Anushasan Parva - Bhishma gives discourse on various other subjects

finally preparing Yudhishthira to become a good ruler.

14.Ashwamedha Parva - Pandavas conduct the Ashwamedha sacrifice and

establish their dominion.

15.Ashramavasika Parva - The elders of the house retire to the forest

where they eventually meet their end due to a forest fire.

16.Mausal Parva - Realisation of Gandhari's curse and the end of the

Yadavas.

17.Mahaprasthanika Parva - The Pandavas retire and begin their journey

towards Swarga. This is the shortest chapter.

18.Swargarohanika Parva - The final chapter that describes the ascent of

Yudhishthira to Swarga and his meeting with his family. Everybody

returns to their respective abode.

Later, a chapter called Harivamsa describing the early life of Krishna was

added to the epic as an appendix.

MAHABHARATA: A STOREHOUSE OF STORIES- DECHEN

Mahabharata- A Storehouse of Stories and the four main dialogues-

Vaisampayana, Bhishma, Ugrasravas, Sanjay.

The Mahabharata stands as a monumental storehouse of stories,

encompassing a vast array of narratives that transcends time and morality.

Comprising over 100,000 shlokas or poetic verses, this epic is a treasure trove

of wisdom, profound teachings and it contains a sleuth of ethical dilemmas.

Within its expansive narrative, four main dialogues emerge as pivotal

components. Vaisampayana, the narrator, provides a comprehensive account

of the Kurukshetra War and the events leading up to it. Bhishma, the grand

patriarch, imparts invaluable insights on dharma (duty) and righteousness.

Ugrasrava, the storyteller, narrates the epic to a gathering of sages,

preserving its oral tradition. Sanjaya, blessed with divine sight, offers a

unique perspective on the battlefield, narrating the events to King

Dhritarashtra. These four dialogues intricately weave the fabric of the

Mahabharata, each contributing to the epic's multifaceted exploration of

human existence and between right and wrong.

HILTEBEITEL’S PROPOSITION- DAKSHITA

In ‘Rethinking the Mahabharata’, Alf Hiltebeitel offers a unique model for

understanding the great epic. Seeing the Mahabharata as a unified work,

Hiltebeitel claims that it includes interwoven narrative frames that are also

poetic devices. It is interlinked to what Dechen elaborated on a while ago.

According to Alf, there are 3 frames of the narrative- The authorial frame, the

generational frame, and the cosmological frame.

The neutral voice that introduces the epic and keeps it going is the

authorial frame because it represents Vyāsa narrating the

Mahabharata to five of his disciples.

Hiltebeitel believes that the composition of the Mahabharata took

about a couple of generations, and Vaiśampāyan, as Vyāsa's disciple, is

the second generation. So Vaiśampāyan's recitation is the generational

frame.

Finally, Ugraśravas's recitation is the cosmological frame, because it

takes place in the Naimiṣa Forest, which Hiltebeitel identifies as a locus

where stories "transcend time and defy ordinary conceptions of

space".

ON THE MAHABHARATA AS AN EPIC- DECHEN

The Mahabharata stands out as an unparalleled epic in the rich bottomless

pit of world literature, encapsulating the essence of Indian culture,

philosophy, and spirituality. Composed by the sage Vyasa, this colossal work

extends beyond a mere chronicle of the Kurukshetra War, delving into

profound discussions on morality, duty, and the intricacies of human

relationships. With its diverse array of characters, from the virtuous Pandavas

to the complex Kauravas, the epic offers a nuanced exploration of the human

condition. The Bhagavad Gita, a sacred dialogue embedded within the

Mahabharata, serves as a philosophical centerpiece, imparting timeless

teachings on righteousness and the path to spiritual enlightenment. Its

narrative scope, philosophical depth, and cultural resonance make the

Mahabharata not just a literary masterpiece but a reservoir of timeless

wisdom that continues to captivate and inspire.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE MAHABHARATA AS AN EPIC- DAKSHITA

Concludingly, I will provide an overview of the major characteristics of the

Mahabharata as an epic and as a story in brief pointers. I will also share these

with you later, after getting them approved from ma’am because I believe

these points provide a well defined outline of the contents, or you can make

brief notes if you want.

So the mahabharata is believed to have been initially called "Jaya,"

conveying a tale of triumph.

"Mahabharata" can be split into Maha (the great) and Bharata (the

story), suggesting "The Great Story."

An epic is a lengthy heroic poem with a serious theme.

Narration typically begins with an invocation/prayer to the Gods, often

performed by the narrator.

The narrator introduces a central question/theme that shapes the

entire narrative, usually related to a general truth.

Epics are episodic, with interconnected yet logically complete episodes.

Each episode contributes to the overall narrative but can stand alone

logically.

The style of an epic is formal, grand in scope, and eloquent in

expression.

Favours oratory and stylized language, often incorporating epic

conventions and similes.

Epics feature heroes with extraordinary or divine powers.

Heroes may have divine lineage, interact with gods, and draw

strength/knowledge from them.

In the Mahabharata, unlike the Ramayana, no single character is

exclusively heroic, reflecting the complexity of events and characters

over three generations.

Some gods appear as characters, testing the strength and virtues of

important human characters.

Vyas and Krishna are examples of characters with a divine-human

duality.

Each character in the Mahabharata displays a distinct temperament

and moral attitude.

Conflicts between characters represent conflicts between different

value systems.

An epic is expected to conclude positively, promising a better and just

world.

The Mahabharata, with its theme of the fight between good and evil,

aligns with this expectation, emphasizing the conflict between dharma

(righteousness) and adharma (unrighteousness).

The Mahabharata, unlike the Ramayana, is seen as a historical epic,

focusing on human weaknesses rather than an idealized hero.

Characters in the Mahabharata are more numerous and realistic,

reflecting a critical representation of a bygone heroic age.

Suggested that the Mahabharata does not fit the Western model of the

heroic epic but reflects a critical representation of a past heroic age

from a subsequent age of enlightenment.

The Mahabharata places human interactions with gods at the forefront,

with characters dealing with dilemmas and decisions in the divine

context.

So, that was all from the three of us. Although it was lengthy and might have

been a little monotonous but we did our best amalagamate mutiple aspects

into the presentation.

Thank you!

You might also like

- The Wisdom Teachings of Harish Johari on the MahabharataFrom EverandThe Wisdom Teachings of Harish Johari on the MahabharataWil GeraetsNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 IksDocument13 pagesUnit 1 Iksnandinimendiratta894No ratings yet

- Indian Classical LiteratureDocument8 pagesIndian Classical LiteratureAiman AliNo ratings yet

- 06 - Chapter 1Document26 pages06 - Chapter 1Ganesh Prasad KNo ratings yet

- Indian Classical LiteratureDocument6 pagesIndian Classical LiteratureChandra BabuNo ratings yet

- The Secret Esoteric Teachings of the Bhagavad Gita: New Revised EditionFrom EverandThe Secret Esoteric Teachings of the Bhagavad Gita: New Revised EditionNo ratings yet

- Describe How Mahabharata Is A Source of Rich LiteratureDocument2 pagesDescribe How Mahabharata Is A Source of Rich LiteratureManisha ChachraNo ratings yet

- AFRO-ASIAN LITERATURE ReferenceDocument51 pagesAFRO-ASIAN LITERATURE ReferenceDINGLASAN Iris NicoleNo ratings yet

- The Mahabhrata LiteracyDocument5 pagesThe Mahabhrata Literacyapi-185218679No ratings yet

- Classical Indian LiteratureDocument19 pagesClassical Indian LiteratureAnand Choudhary100% (1)

- Sanskrit Story Literature - A Brief Overview: Dr. Rajani JairamDocument4 pagesSanskrit Story Literature - A Brief Overview: Dr. Rajani JairamUpakhana SarmaNo ratings yet

- PanchatantraDocument9 pagesPanchatantraHarshitha Senapathi100% (1)

- Prince of Patliputra: The Asoka Trilogy Book IFrom EverandPrince of Patliputra: The Asoka Trilogy Book IRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Afro Asian ModuleDocument33 pagesAfro Asian ModuleJherick Tacderas100% (1)

- Tattvabodha (Volume VII): Essays from the Lecture Series of the National Mission for ManuscriptsFrom EverandTattvabodha (Volume VII): Essays from the Lecture Series of the National Mission for ManuscriptsNo ratings yet

- Lalitha Sahasranamam With Meaning PDFDocument232 pagesLalitha Sahasranamam With Meaning PDFPrakash Narasimhan88% (16)

- Indian LiteratureDocument19 pagesIndian Literaturedazzle genreNo ratings yet

- Indian - History Told 4Document31 pagesIndian - History Told 4Nigar Fathola Hassan100% (1)

- 9 Afro Asian Literature1Document38 pages9 Afro Asian Literature1Reygen TauthoNo ratings yet

- ShivaDocument7 pagesShivaJoysree DasNo ratings yet

- Dr. ARCHANA KUMARIDocument7 pagesDr. ARCHANA KUMARIKarthik Yss GopaluniNo ratings yet

- Afro-Asian LiteratureDocument24 pagesAfro-Asian LiteratureImelda Arreglo-Agripa67% (6)

- Afro Asian LiteratureDocument24 pagesAfro Asian LiteraturePhclivranNo ratings yet

- The Complete Life of Krishna: Based on the Earliest Oral Traditions and the Sacred ScripturesFrom EverandThe Complete Life of Krishna: Based on the Earliest Oral Traditions and the Sacred ScripturesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (8)

- For the Lord of the Animals-Poems from The Telugu: The Kalahastisvara Satakamu of DhurjatiFrom EverandFor the Lord of the Animals-Poems from The Telugu: The Kalahastisvara Satakamu of DhurjatiNo ratings yet

- 6501-Article Text-11952-1-10-20210516Document5 pages6501-Article Text-11952-1-10-20210516yugendran kumarNo ratings yet

- Aryavarta Chronicles Kaurava - Book 2, The - Krishna UdayasankarDocument2,316 pagesAryavarta Chronicles Kaurava - Book 2, The - Krishna UdayasankarParam Study100% (1)

- Afro Asian LiteratureDocument29 pagesAfro Asian LiteratureLailaniNo ratings yet

- Journal Homepage: - : IntroductionDocument10 pagesJournal Homepage: - : IntroductionIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Afro Asian Literature RepairedDocument23 pagesAfro Asian Literature RepairedPrecious Acebuche100% (1)

- From One Birth to Another: Stories from Jaina LiteratureFrom EverandFrom One Birth to Another: Stories from Jaina LiteratureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Afro Asian Literature and Mythology and FolkloreDocument28 pagesAfro Asian Literature and Mythology and FolkloreRosé SanguilaNo ratings yet

- Project 4Document38 pagesProject 4Sreelekshmi PushpanNo ratings yet

- The Mahabharata: A Shortened Modern Prose Version of the Indian EpicFrom EverandThe Mahabharata: A Shortened Modern Prose Version of the Indian EpicRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- UruhduDocument4 pagesUruhduKarthi Keyan RNo ratings yet

- ExercisesDocument20 pagesExercisesthefrozen99No ratings yet

- Aristotle's Poetics & Oedipus - DictionDocument13 pagesAristotle's Poetics & Oedipus - DictionA Hughes50% (2)

- In What Ways Does John Fowler Play With Textual Form and Feature in Order To Transform IdeasDocument3 pagesIn What Ways Does John Fowler Play With Textual Form and Feature in Order To Transform IdeasBrenda LiNo ratings yet

- Imagination and Fancy by Coleridge - Term PaperDocument5 pagesImagination and Fancy by Coleridge - Term PaperBidyut Barman100% (1)

- Self AssessmentDocument8 pagesSelf AssessmentPepaNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan in OEDIPUSDocument9 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in OEDIPUSrica mae bernadosNo ratings yet

- Orpheus Script.1.1.1Document8 pagesOrpheus Script.1.1.1Dwight CiervoNo ratings yet

- ROSAND, E. La VIA, ST.,, Claudio Monteverdi's Venetian Operas Sources, Performance, Interpretation, 2022Document297 pagesROSAND, E. La VIA, ST.,, Claudio Monteverdi's Venetian Operas Sources, Performance, Interpretation, 2022ANA LUISA NUNES DE VARGASNo ratings yet

- ABC Family Friends Teacher GuideDocument45 pagesABC Family Friends Teacher GuideLizzie Maldonado LessaNo ratings yet

- English B Poems and Plays AnalysisDocument84 pagesEnglish B Poems and Plays Analysiscarlissia wilkinsNo ratings yet

- Jessa Mae Francisco Lit Worksheet 1Document2 pagesJessa Mae Francisco Lit Worksheet 1Chelsea MeereNo ratings yet

- (Upakarma) Avani Avittam: (Mantram For Wearing Poonal)Document13 pages(Upakarma) Avani Avittam: (Mantram For Wearing Poonal)Anand RajgopalNo ratings yet

- English6 Ans WBDocument26 pagesEnglish6 Ans WBSonal AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Q&A Tom FeltonDocument2 pagesQ&A Tom FeltonKootjeAustenNo ratings yet

- Midsummer Night's DreamDocument6 pagesMidsummer Night's DreamJiaXuanDeNo ratings yet

- Return of The Native SparknotesDocument3 pagesReturn of The Native Sparknotesfatimatuzahra503No ratings yet

- Yoga VasisthaDocument6,956 pagesYoga VasisthaPraveen Meduri0% (1)

- Nat Reviewer 6Document5 pagesNat Reviewer 6Ronah Vera B. TobiasNo ratings yet

- 12 05 2022 Screening ScheduleDocument3 pages12 05 2022 Screening ScheduleAnzil AzimNo ratings yet

- Hatim AlDocument2 pagesHatim AlKim EliotNo ratings yet

- KamalDocument2 pagesKamalPunnakayamNo ratings yet

- Rudraksha Jabala UpanishadDocument8 pagesRudraksha Jabala Upanishadmysticbliss100% (2)

- Goy-erica-Varuna The Judgemental GodDocument6 pagesGoy-erica-Varuna The Judgemental GodJoaquín Porras OrdieresNo ratings yet

- 1575061295Document386 pages1575061295luisimbach100% (4)

- Doctors: List of Doctors and Medical Services in The Dominican Republic - May 2006Document7 pagesDoctors: List of Doctors and Medical Services in The Dominican Republic - May 2006Otpor StokoNo ratings yet

- 2012 Fall IPG General Trade CatalogDocument268 pages2012 Fall IPG General Trade CatalogIndependent Publishers GroupNo ratings yet

- The Quest For Identity in Sherman AlexieDocument10 pagesThe Quest For Identity in Sherman AlexieEzekielNo ratings yet

- Invictus Utilizes More Compelling Figurative Language and Imagery. Henley Starts HisDocument3 pagesInvictus Utilizes More Compelling Figurative Language and Imagery. Henley Starts Hisapi-385678267No ratings yet

- Beowulf - S IntroductionDocument2 pagesBeowulf - S IntroductionPaula FavettoNo ratings yet