Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Retreating State? Political Economy of Welfare Regime Change in Turkey

Uploaded by

Muhammed DönmezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Retreating State? Political Economy of Welfare Regime Change in Turkey

Uploaded by

Muhammed DönmezCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/233605480

Retreating State? Political Economy of Welfare Regime Change in Turkey

Article in Middle East Law and Governance · August 2010

DOI: 10.1163/187633710X500739

CITATIONS READS

123 1,728

1 author:

Mine Sadiye Eder

Bogazici University

22 PUBLICATIONS 513 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Mine Sadiye Eder on 17 January 2018.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2009) 152–184 brill.nl/melg

Retreating State? Political Economy of Welfare Regime

Change in Turkey

Mine Eder

Boğazici University, Istanbul, Turkey1

Abstract

Informed by the debates on the transformation of welfare states in advanced industrial econo-

mies, this article evaluates the changing role of the state in welfare provision in Turkey. Turkey’s

welfare state has long been limited and inegalitarian. Strong family ties coupled with indirect and

informal channels of welfare (ranging from agricultural subsidies to informal housing—both

costly but politically expedient) have compensated for the welfare vacuum. At first glance,

Turkey’s welfare reform that emerged from the 2000-2001 fiscal crisis appears like a classic case

of moving towards a minimalist, ‘neoliberal’ welfare regime—with increasingly privatized health

care and private social insurance. The state retreats via the subcontracting of welfare provision to

private actors, growing involvement of charity organizations, and increasing public-private coop-

eration in education, health, and anti-poverty schemes. Yet, there is also evidence of the expan-

sion of state power. The newly empowered ‘General Directorate of Social Assistance and Solidarity

(SYDGM)’ manages an ever-increasing budget for social assistance, the number of mean-tested

health insurance (Green Card) holders explodes, health care expenditures rise substantially, and

municipalities become important liaisons for channeling private money and donations for anti-

poverty purposes. The cumulative effect is an ‘institutional welfare-mix’ that has actually mutated

so as to compensate for the absence of the earlier, politically attractive but fiscally unsustainable

welfare conduits. The result has so far been the creation of immense room for political patronage,

the expansion of state power, and no significant improvement of welfare governance.

Keywords

Turkey; welfare reforms; patronage

Agricultural subsidies in this country should actually be seen as unemployment insurance.

You cannot and should not get rid of them overnight.

—Süleyman Demirel, seven-time prime minister and president in Turkey,

in an interview in August 17, 2002 Finansal Forum

1)

I would like to thank Yale University, Council of Middle East Studies and the editors of this

special issue for their support and feedback during the writing of this article.

© Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2010 DOI 10.1163/187633710X500739

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 152 4/13/2010 2:19:32 PM

M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184 153

Debates on globalization have long focused on the question of retreat or sur-

vival of states in the midst of growing international competition. Whether the

governments can sustain their earlier welfare commitments or whether they

will have to decrease their social expenditures while privatizing (and/or sub-

contracting) public social services has become the primary testing ground for

such debates. Among the students of comparative political economy, this

debate took the form of whether there is a growing institutional convergence,

i.e. growing ‘similarity in structures, rules, procedures and processes’2 towards

a limited, ‘minimalist’ ‘liberal’ welfare state, or whether there are still lingering

divergent welfare states based on political and economic compromises and

institutional legacies.3

That there is significant variety in terms of responses, institutional forms,

and the political context within which these welfare states are changing is

clearly not surprising. In fact, almost the entire literature on the development

of welfare state and Esping-Anderson’s now classic work on Three Worlds of

Welfare Capitalism (1990) and later his Social Foundations of Post-Industrial

Economies (1999) are based on analyzing the differences between how the

states, markets and households created different patterns of social provision in

different countries and produced very different welfare outcomes. Anderson’s

typology, for instance, was primarily based on income maintenance and labor

market practices and focuses on the degree to which labor is de-commodified,

i.e., is protected from the market forces. The political settlement between

labor, capital and state since WWII, he argued, has created different institu-

tional legacies and outcomes. It is precisely these institutional legacies and the

early political compromises that are then likely to shape the degree of retrench-

ment and reform of the welfare states, accounting for different welfare

trajectories.

Surprisingly, however, very little of these debates on the changing role of the

state and ‘varieties of welfare states’ has spilled over to the discussions on wel-

fare reforms in the developing countries.4 This may largely be thanks to the

2)

C. Kerr, The Future of Industrial Societies: Convergence or Continuing Diversity (Cambridge:

Harvard University Press, 1983), 3.

3)

Esping-Anderson, Social Foundations of Post-Industrial Economies (Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 1999); P. Hall and D. Soskice, Varieties of Capitalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press,

2001); E. Huber and J. Stephens, Development and the Crisis of Welfare State (Chicago: Chicago

University Press, 2001); H. Kitschelt et al., Continuity and Change in Contemporary Capitalism

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

4)

E. Huber, ed., Models of Capitalism: Lessons for Latin America (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania

University Press, 2002); E. Kapstein and B. Milanovic, When Markets Fail: Social Policy and

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 153 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

154 M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184

significant differences between the ‘mature’ welfare states and the developing

countries. Four common features in the developing countries make such an

application difficult. First, the concepts of ‘welfare state’ and ‘social policy’

privilege the state in terms of social provision. In most of the developing coun-

tries, the welfare states and government-led social policy framework are either

not developed or its coverage is too limited. There are other actors such as the

family, community groups, NGOs, and private initiatives that have actively

participated in social provision. Thus following Gough5 using the term welfare

regime, as ‘a more generic term referring to the entire set of institutional

arrangements, policies and practices affecting the welfare outcomes and strati-

fication effects in diverse social and cultural contexts’ can be more useful,

acknowledging the wide-variety of institutional ‘welfare-mix’.

Second, and perhaps most importantly, Anderson’s typology assumes a ‘rela-

tively autonomous state’ with a structural power, capable to respond to various

class interests and social demands. This image of clearly defined state-society

boundaries is also hardly applicable to the developing countries where the

state is often extremely ‘permeable’.6 For example, either international pres-

sures (mostly via the World Bank and the IMF) are visible and/or domestic

clientelistic and particularistic interests often overshadow the pursuit of long-

term public interests.

Third, using the concept of de-commodification of labor, is highly problem-

atic in countries where the informal labor market are vast and that social,

informal networks operate very differently than the contractual, impersonal

labor markets. This extensive informal market suggests that labor is not

fully commodified to begin with. The significant percentages of rural popula-

tion with subsistence agriculture and the abundance of non-wage labor (share-

cropping, peasant agriculture, family labor, outworking, subcontracting etc.)

Economic Reform (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2002); S. Haggard and R. Kaufmann,

eds., Development, Democracy and Welfare States: Latin America, East Asia and Eastern Europe

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008); N. Rudra, ‘Globalization and the Decline of the

Welfare State in Less-Developed Countries,’ International Organization 56.2 (2002): 411-445;

N. Rudra, ‘Welfare States in Developing Countries: Unique or Universal?’ The Journal of Politics

69.2 (2007): 378-396; I. Gough and G. Wood, eds., Insecurity and Welfare Regimes in Asia, Africa

and Latin America: Social Policy in Development (London: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

5)

I. Gough, ‘Welfare Regimes in Development Contexts: A Global and Regional Analysis,’ in

Insecurity and Welfare Regimes in Asia, Africa and Latin America: Social Policy in Development, eds.

Gough and Wood (London: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 26.

6)

Ibid. (Gough and Wood).

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 154 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184 155

also make the use of the de-commodification concept difficult. Equally impor-

tant is the very different roles women assume in most of the developing coun-

tries in and outside the family, which is completely neglected in this framework.

Women play the most crucial part in welfare provision across the developing

world, particularly when it comes to children and elderly care.

Finally, the political mobilization can also take very different forms; hence

the politics of welfare regime change is also likely to be quite different in the

developing country contexts. Class power or various economic interest groups

may not necessarily be the most important agents of political mobilization.

Ethnicity, religion, caste, kinship or other interpersonal networks may actually

capture the political landscape more effectively thus complicating our under-

standing as to why and how such shifts in welfare regimes occurs in these

countries. Going back to the state-society relations, the legacies of the earlier

welfare regime and the political compromises associated with the earlier wel-

fare regimes along with economic push factors can provide better insights on

the nature and direction of welfare reform.

Focusing on the political economy of welfare regime change in Turkey,

which started slowly in the 1980s but accelerated in the aftermath of the

2000/2001 financial crises in the country, this article uses the Turkish case

to highlight some of the problems associated with the assumption of ‘capable,’

and ‘autonomous’ states undertaking reforms. The examples from mature

welfare states can still be insightful, however, as the nature of welfare regime

change will depend on the legacies of prior welfare regimes as well as on the

political opportunity structure it creates for the governments. That is why

characterisation of the welfare regime change in Turkey as a convergence

towards a neoliberal paradigm with the retreat of the state, or as a com-

pletely divergent case of new welfare etatisme, too unique to be compared to

other countries, can be highly problematic.7 Despite the seeming retreat of

the state from welfare provision and privatization of some of these social ser-

vices, there is a growing diffusion, de-centralization, political expansion and,

7)

There is a tremendous variety in the language here. Jessop talks about transformation from

welfare to workfare state, Phil Cerny, talks about ‘competition state,’ Susan Strange discusses the

‘retreat of the state,’ more recently Rudra uses cluster analysis for classifying ‘productive’ welfare

states in LDCs, promoting market reforms and ‘protective’ welfare state protecting select indi-

viduals from the market and a dual welfare state which manifest both trends. See P. Cerny,

‘Paradoxes of the Competition State: The Dynamics of Political Globalization,’ Government and

Opposition 32.2 (1997): 251-274; S. Strange, Retreat of the State: Diffusion of Power in World

Economy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996); Rudra, 2007 (see note 4).

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 155 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

156 M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184

perhaps paradoxically, ‘continual formation of the state’.8 Indeed, as the state

starts subcontracting and privatizing some of its social services and transfers

some of the responsibilities to other actors—i.e. municipalities, foster parents,

private hospitals—and moves away from a ‘social state,’ towards what one can

call a ‘social assistance state,’ opportunities for political appropriation of

funds, the politicization of various distribution channels of social welfare

abound.

As discussed below, there is clear evidence for both retreat and extension of

state’s political power in the case of Turkey. The state does indeed retreat from

directly providing social services through either financing the private sector or

households to provide such services, (which may actually mean, at least in the

short run, increase in social expenditures) and/or transfer of these services to

private actors entirely, thereby presumably shifting to a ‘regulatory’ role. Yet,

there is also evidence that the state, in assuming an increasingly controlling

role, stretches its increasingly politicized power into various aspects of social

and economic life. As the social assistance funds and transfers in the country

skyrocket out of control, as the empowered municipalities work in private

partnerships to assume new responsibilities in social services, and as the NGOs

are empowered through legal changes to collect donations for the ‘causes’ of

their own choosing, this ‘social assistance state’ actually increases its political

power, adapting to changing demands. The reason the welfare regime change

in Turkey involves both the retreat of the state and the extension/politicization

of state power is a result of both the legacies of the old welfare regime, with the

economic push factors which made it unsustainable, and the political pull fac-

tors since governments, when given the opportunity, normally choose politi-

cally expedient ways to expand their political power.

Mapping Turkey’s Old ‘Indirect’ Welfare Regime

With more than half of its workforce employed in the informal sector (a stag-

gering 87 percent of those employed in the agricultural sector) almost

40 percent of its overall population does not have healthcare.9 Turkish gov-

ernments have long struggled with the challenges of addressing the social

8)

B. Hibou, ‘Domination and Control in Tunisia: Economic Levers for the Exercise of

Authoritarian Power,’ Review of African Political Economy 108 (2006): 185-206.

9)

All numbers are from TUIK unless otherwise indicated.

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 156 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184 157

security needs of its rapidly growing population sharing many characteristics

of welfare regimes in the developing countries described above. Nevertheless,

the fact that abject poverty10 has been relatively small, even during the worst

of economic times (a little above 2 percent), suggests that despite its limita-

tions, Turkey’s institutional ‘welfare mix’ has not been a total disaster.

But Turkey’s limitations of the social policy framework were all but evi-

dent from the very start. Simply put, the formal social policy in Turkey has

long been based on the provision of free primary, secondary and tertiary edu-

cation, coupled with public health care and a pension system which were all

linked to the employment status. Founded in 1949, Retirement Chest has

provided health care and pension for civil servants, and Social Insurance

Institution, founded in 1946, covered the workers. The self-employed were

covered by Bagkur, which was founded in 1971. (Table 1 shows the number

of people covered in each insurance scheme.) As the table indicates, nearly half

of the working population are still not covered by any of these insurance

schemes, working entirely informally in the labor market. High dependency

ratios also indicate a strikingly low employment rate in the country. Between

1980 and 2004, the working age population grew by 23 million, but only

6 million jobs were created. The result is a 44 percent employment ratio,

which is among the lowest in the world. Another striking feature, and one of

the fundamental reasons of low employment rates in the country, is the female

participation rate. The female employment rate has been declining since

the 1960s and has hovered around 20 percent, half that of its European

counterparts.11

It is not surprising then that a low employment ratio coupled with a high

degree of informality in the labor markets has really widened the gap between

those employed formally and those employed in the informal sector. Those

with insurance premiums paid by the employer (until the 2007 social security

reform, the Turkish state did not contribute at all to the insurance schemes)

and those who have neither coverage nor access to basic health care. What is

striking is the contrast between the privileged and easily accessible services and

protection for the working population and the absence of any alternatives for

the rest. The numbers are particularly striking in the rural sector where, on

10)

Defined as under one dollar a day according to UNDP.

11)

World Bank, Labor Market Study: Summary Turkey World Bank Document (Turkey: World

Bank, April 14, 2006), 4-7, http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTTURKEY/Resources/

361616-1144320150009/Ozet-Overview.pdf.

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 157 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

158 M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184

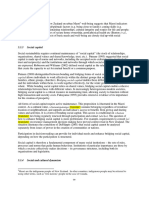

Table 1. Population covered by social insurance programs (1998-2005)

SSK Emekli Sandığı Bağkur

Workers Retirement Self-

Chest of Employed

Civil Servants

1998 5,323,434 2,071,867 1,911,259

1999 5,030,732 2,118,085 1,939,593

Number of active 2000 5,283,234 2,156,176 2,181,586

members 2001 4,913,939 2,236,050 2,198,200

2002 5,256,741 2,372,777 2,192,555

2003 5,655,647 2,408,148 2,224,247

2004 6,229,169 2,404,091 2,212,299

2005 6,965,937 2,402,409 2,103,651

Membership Coverage in total 1998 24,4 9,51 8,77

Figures employment (%) 1999 22,81 9,6 8,79

2000 24,48 9,99 10,1

2001 22,8 10,38 10,21

2002 24,61 11,11 10,26

2003 26,74 11,38 10,51

2004 28,58 11,03 10,15

2005 31,59 10,89 9,54

Number of 1998 23,095,667 4,548,789 9,206,911

dependants 1999 21,469,875 4,635,514 9,655,546

2000 22,541,181 4,777,090 10,446,180

2001 21,592,466 4,980,651 10,601,159

2002 22,993,730 5,255,878 10,832,989

2003 24,610,697 5,363,274 11,051,955

2004 26,771,763 5,331,249 11,266,245

2005 29,447,871 5,272,130 11,035,587

Dependency ratios 1998 4,33 2,19 4,81

1999 4,26 2,18 4,97

2000 4,26 2,21 4,79

2001 4,39 2,22 4,82

2002 4,37 2,21 4,94

2003 4,35 2,22 4,96

2004 4,29 2,21 5,09

2005 4,22 2,19 5,24

Source: SPO.

average, the lack of any social insurance has systematically been around

85 percent of the agricultural labor force. In the case of women who are

counted as ‘employed in family farms as unpaid family workers,’ nearly 100

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 158 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184 159

percent do not have any insurance.12 Given the fact that until very recently,

rural employment still counted for 40 percent of total employment the con-

trast becomes even greater.

Welfare provision and social policy framework in Turkey have also been

based on informal strategies, implicit social pacts, compromises and most

importantly family ties and informal personal networks. Unlike its Latin

American and South European counterparts, Turkey has not developed well-

funded social assistance programs to address these economically vulnerable

sectors. Instead, Turkey used: (a) extensive agricultural subsidies along with

tax exemption of the rural sector; (b) the possibilities of informal housing in

the urban areas where the public land could easily be invaded by irregular set-

tlers, and, as is common with most of the developing world, and; (c) extensive

private family and social networks. These three factors have long been the

foundation of the country’s welfare regime and have largely been responsible

for the relative absence of violent dispossession, extreme poverty, rapid

commodification and/or social unrest. Both the agricultural subsidy programs

as well as the ‘deliberate negligence’ on informal urban housing provided

ample room for populism.13

a) Agriculture

Three main features of Turkey’s agriculture have been instrumental in main-

taining what can be called ‘indirect welfarism’ in Turkey. With the exception

of a brief period in the 1980s, product subsidies were persistently high until

2001, well above world prices. Combined with the habitual registration

of the non-performing farmers’ credits as ‘duty losses’ of the Ziraat Bankası,

(a national bank predominantly designed to provide credits and receive depos-

its from the farmers) it became one of the main characteristics held account-

able for the huge fiscal deficits in the country since the 1960s. Non-existing,

or extremely low levels of taxation from agriculture and production based on

small land ownership comprise the other two unique characteristics of Turkey.

About 60 percent of the rural families own less than five hectares of land and

12)

As these women migrate to the cities, they will be recorded as unemployed which explains the

further decline in female labor participation as rural employment numbers decrease particularly

since 2000.

13)

A. Bugra and C. Keyder, New Poverty and Changing Welfare Regime in Turkey, United Nations

Development Programme report, 2003; A. Bugra and C. Keyder, ‘The Turkish Welfare Regime

in Transformation,’ Journal of European Social Policy 16 (2006): 211-228.

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 159 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

160 M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184

another 20 percent between five and ten hectares.14 Mostly because of the

availability of land, and thanks to policies and concerns dating back to the

Ottoman era (large landowners were always perceived as threats to the central

government), small landownership has persisted until now; Kurdish southeast

regions and a few valleys in Söke and Çukurova are the only exceptions.

The small peasantry and agriculture which persisted in Turkey’s economy

until the 1980s actually dates back to the early republican political compro-

mise, wherein the new single-party government eliminated the agricultural

tithe (aşar) in 1925. As a strategy to address the intense rural poverty that

plagued the countryside, it meant to ensure peasants’ loyalty to the new repub-

lic. Several attempts to place taxes on agriculture have failed since then, as

there were ongoing political concerns of social unrest, mass migration, massive

dispossession and arguably a social explosion. More importantly, however, the

persistence of a large rural population, thanks to small landownership, also

meant that agricultural policies and subsidies became prime areas of political

and populist contestation. So much so, that the politicians since the 1950s

have consistently found themselves in a populist competition, outbidding

each other in terms of agricultural base prices (prices at which the government

guarantees to buy from the farmers).15

Not surprisingly, the product subsidy equivalents (PSEs) have been consis-

tently high in Turkey. 86 percent of the PSE has emerged from price support

and 14 percent from import subsidies. Kasnakoğlu has calculated that until

1998,Turkey’s producer support reached an annual $2500 farming household

and $500 per farming person. For full-time farmers, this number reached as

high as $1000 which corresponds to half of the per capita rural income.16 The

ratio of total agricultural transfers to the GDP has been consistently higher

than the OECD average. (Average 8 percent, for instance in 1997-99 period

as opposed to OECD average of 1.3 during the same period).17

14)

H. Kasnakoglu, ‘The Impact of Agricultural Adjustment Programs on Agricultural

Development and Performance in Turkey,’ FAO (June 2004), Ankara; M. Eder, ‘Political

Economy of Agricultural Liberalization in Turkey,’ in La Turquie et le developpement, ed. A. İnsel

(Paris: L’harmattan, 2002), 211-244.

15)

M. Eder, ‘Populism as a Barrier to Integration with the EU: Rethinking the Copenhagen

Criteria,’ in Turkey’s Europe: An Internal Perspective On EU-Turkey Relations, eds. Mehmet Uğur

and Nergis Canefe (New York: Routledge, 2004), 49-74.

16)

H. Kasnakoğlu and E. Çakmak, Tarım Politikalarında yeni denge arayışları ve Türkiye (Istanbul:

TUSIAD Publications, 1996), 61.

17)

OECD, Agricultural Policies in OECD Countries: Monitoring and Evaluation 2000 (Paris:

OECD Publications, 2000), 245.

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 160 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184 161

Nevertheless, despite high costs and the ample opportunities of a political

compromise based on successive governments foregoing their tax revenues,

spending huge sums on product subsidies created for political patronage, it is

clear that, as Suleyman Demirel has suggested, these policies have managed to

cushion the rural population from extreme forms of poverty, providing them

with some sort of unemployment insurance. The seven-time prime minister

entered the history books upon coining a famous political slogan. Addressing

the peasants in his election campaigns, the fundamental political constituency

of his party, he said: ‘Do not worry, I will always give you 5 Turkish liras more

that the other parties as the base price of your product.’18

b) Informal Housing

If agricultural policies aimed at keeping the peasants in the countryside, over-

looking or perhaps deliberately neglecting informal housing in the urban areas

has been the predominant strategy to ease the pressures of migration and inte-

gration to the cities. As in most of the irregular settlements in the developing

world, gecekondus (literally means landed-overnight in Turkish) was an out-

come of the inability of the governments to provide low income housing to

address the problem of rapid urban migration, which despite all the agricul-

tural strategies cited above, began to skyrocket in the 1960s. As Bugra reports,

‘In the first half of the 1960s, 59 percent of the population in Ankara,

45 percent in Istanbul and 33 percent in Izmir lived in irregular settlements.’19

18)

S. Pamuk, ‘Economic Change in Twentieth Century Turkey: Is the Glass More Than Half

Full?’ in Cambridge History of Modern Turkey, ed. Resat Kasaba (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 2008), 294. As Pamuk summarizes:

Large productivity and income differences between agriculture and urban economy have

been an important feature of the Turkish economy since the 1920s. Most of the labor force

in agriculture is self-employed in the more than 3 million family farms, including a large

proportion of the poorest people in the country. The persistence of this pattern has not

been due to the low productivity alone, however. If the urban sector had been able to grow

at a more rapid pace more labor would have left the countryside during the last half cen-

tury. Equally important, governments have offered very little amounts of schooling to the

rural population in the past. Average amount of schooling of the total labor force (ages

fifteen to sixty-four) increased from only one year in 1950 to about seven years in 2005.

The average years of schooling of the rural labor force today is still below three years, how-

ever. In others words, most of the rural labor force today consists of undereducated men

and women, for whom the urban sector offers limited opportunities.

19)

Ayse Bugra, ‘Immoral Economy of Housing in Turkey,’ International Journal of Urban and

Regional Research 22 (1998): 307.

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 161 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

162 M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184

The peculiar aspect of gecekondus in Turkey, however, was the fact that they

were mostly built on available public land in the cities (75-80 percent).20 The

land was simply invaded and appropriated mostly by the new migrants into

the city.

This deliberate negligence of informal housing was again a result of a politi-

cal compromise. The governments could manage a possible urban social unrest

through informal housing and ease its burden of having to deal with the

immediate implications of migrations to the cities. Meanwhile, the new

migrants found a way, however immoral and unfair it may have been, to ease

their transition to the cities and experience what came to be classically dubbed

as ‘poverty-in turns’. Previous migrants moved to better, improved houses and

integrated into the city, leaving room for the new migrant poor.21 Once again,

however, such a political compromise created an enormous opportunity of

political patronage mechanisms, and clientelism, as land titles would most

likely be distributed prior to local elections.

A total of seven amnesty laws passed since the 1950s, regarding regularizing,

legitimizing and legalizing the gecekondus, and allowing them to receive equal

municipal services.22 The distribution of land titles in return for votes became

a typical political strategy. Moreover, gecekondus themselves eventually

became commercialized themselves.23 Through improving the physical condi-

tions of the buildings, disregarding aesthetics, and at times even turning them

into semi-cities (as Erder aptly demonstrated in the case of Ümraniye),24 these

buildings created additional income, rent opportunities and eventually addi-

tional income through sales to newcomers, most of whom would often be

their hemşeris (provincial brothers).

What the above picture on Turkey’s informal welfare regime implies is that

the states have often lacked the institutional capacity to provide a full-fledged

social services and quality welfare. However, populist policies at the macro

level along with over-reliance on family networks have compensated for some

of the in-egalitarian corporatist aspects of the regime, which over-privileged

20)

Ibid., 309.

21)

M. Pınarcıoglu and Oguz Işık, Nöbetleşe Yoksulluk: Gecekondulaşma ve Kent Yoksulları,

Sultanbeyli örneği: Rotating poverty: Slums and Urban Poverty (Istanbul: İletisim, 2001).

22)

I. Tekeli, Gecekondu maddesi Istanbul Ansiklopedisi (Istanbul: Tarih Vakfi, 1993).

23)

A. Öncü, ‘The Politics of the Urban Land Market in Turkey: 1950-1980,’ International

Journal of Urban and Regional Research 12 (1988): 38-64; Bugra, 1998 (see note 18).

24)

Sema Erder, Istanbul’a bir kent kondu: Ümraniye, (A city landed in Istanbul) (Istanbul: İletişim,

1996).

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 162 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184 163

the workers but under-privileged the informal workers and the unemployed.

In her analysis of the reasons behind the dominance of the public sectors in

late-industrializing developing economies, Chaudhry argues that this domi-

nance was not due to the strength of the state but ironically thanks to its weak-

ness; an inability to create and regulate a market economy.25 A similar argument

can indeed be made within the context of the informal welfare regime in

Turkey as it reflects the lack of institutional capacity on the part of the state

and the need to resort to rather crude, populist, and ultimately costly, welfare

instruments.

Pressures for Change: Indirect Welfare Cushions under Strain

While most of the pillars of indirect welfarisms were seriously strained since

the 1980s, the social and economic impact of their collapse became all the

more visible since the 2000/2001 financial crises. Given their fiscal burden,

it is no surprise that agricultural policies became the main target of reform.

In fact, the implementation of agricultural reform implementation pro-

gram (ARIP), guided and supported by the World Bank, became a structural

benchmark for IMF lending in the aftermath of the financial crisis and this

accelerated changes in the agricultural production and the labor market.

Among its main changes ARIP envisioned was the elimination of product and

input subsidies, and a transition to direct income subsidy support for the

farmers.

One result has been the precipitous decline in agricultural employment.

The ratio of agricultural workers in total employment declines from 40 per-

cent in 1998 to 29.5 percent in 2005 and 27.3 percent in 2006,26 and an

estimated three million agricultural jobs have been lost since the financial

crisis of 2001.27 Furthermore, since the corresponding job growth in the urban

sectors was insufficient (in effect, Turkey went through the experience of

jobless growth along with many of the countries around the world), the pres-

sures of unemployment remained constant and high. All these developments

25)

Kiren Aziz Chaudhry, ‘The Myths of the Market and the Common History of Late

Developers,’ Politics and Society (September 1993): 245-274.

26)

Republic of Turkey Prime Ministry Undersecretariat of Treasury, www.treasury.gov.tr.

27)

B. Karapınar, ‘Rural Transformation in Turkey 1980-2004: Case Studies from Three Regions,’

International Journal of Agricultural Resources, Governance and Ecology 6, no. 4/5 (2007):

483-513.

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 163 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

164 M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184

essentially meant that informal welfare mechanisms through agricultural poli-

cies would no longer be available, which is also visible in the persistently high

degree of poverty in agriculture in comparison to the other sectors. Ratio of

poor individuals among the employed members (fifteen years old and above)

in agriculture were 33 percent in 2006, but 10 percent among those employed

in the industry and 7 percent employed in services.

Meanwhile, the prospect of using informal housing as a welfare measure

had long started dimming as urban landscape started becoming rapidly

saturated and commodified.28 Two major trends accelerated this process and

transformed the urban land into an area of social and political contestation.

One was the increasing devolution of power to the municipalities. In 1984,

the Motherland Party who enjoyed the parliamentary majority passed a

Construction law enabling the municipalities to prepare and approve urban

construction and land development. Needless to say, this change opened a

flurry of rent seeking activities, allowing the municipalities to subcontract

giant urban development and construction projects, as well as residential com-

plexes to the private sector. As urban real estate became a highly valuable com-

modity, and fully privatized, the so-called regularization of irregular settlements

had turned into the expansion of the city limits. Middle and upper middle class

suburban houses were often built with dire environmental consequences.29

Globalization and influx of foreign capital into the cities, which once again

increased the prospects for rent seeking for the municipalities, also fastened

this process of appropriation of land.30

Thus it is not surprising that despite ongoing controversies on measuring

and assessing poverty, there is a general consensus that the risk of poverty,

particularly in the aftermath of the financial crisis, has been on the rise in the

country. More than one million jobs were lost and many small businesses went

bankrupt. In 2008, the OECD report highlighted Turkey with the highest

rate of increase in child poverty and urgently called for a targeted poverty

28)

C. Keyder, ‘Globalization and Social Exclusion in Istanbul,’ International Journal of Urban

and Regional Research 29, no. 1 (2005): 124-134; C. Keyder, ‘Transformations in Urban Structure

and the Environment in Istanbul,’ in Environmentalism in Turkey: Between Democracy and

Development?, eds. F. Adaman and M. Arsel (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005), 201-215.

29)

Bugra, 1998, 312 (see note 18).

30)

Keyder describes the physical transformation of Istanbul a la globalization: gated communi-

ties, five-star hotels, city packaged as consumption artifact for tourists, new office towers, expul-

sion of small business from central districts, beginnings of gentrification in old neighborhoods

and world images on billboards and shop windows. Keyder, ‘Globalization and Social Exclusion

in Istanbul,’ 128 (see note 26).

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 164 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184 165

alleviation program. According to 2003 Euro stat data, the percentage of

children in Turkey under the age of sixteen with poverty risk was 34 percent,

twice the EU-25 average.

In a 2004 urban household survey, when asked their last six month’s average

family income, including the wages, pensions and rental income of all the

family members, 51.6 percent of households indicated that their income was

below 600 dollars/month. While one third of households reported income

levels between 600-1200 dollars, only 13.3 percent reported income higher

than 1,200 dollars. Based on these declared incomes, those who have a per

capita household income of approximately 2.5 dollars a day or less (approxi-

mately 100 YTL) can be considered economically vulnerable. Though most

economic vulnerability indexes are based on consumption and the cost of

basic and non-basic goods, we used income numbers, but with a much lower

threshold, as individuals are very likely to understate their income. Based on

the threshold of 100 YTL and less declared income, we found that 24 percent

of households had a per capita household income of 100 YTL, which is com-

parable to TUIK numbers.31

Ownership patterns reflect a very similar picture in terms of degree of eco-

nomic vulnerability and poverty. 76.2 percent in our survey did not have a car

in the household, and approximately 40 percent of the urban households do

not own their houses. These findings are also in line with ‘risk of-poverty’

rates, defined as 60 percent of median of the equalized net income of all house-

holds. In 2003, 26 percent of the Turkish population was below this line.

More striking is the high rate observed among the working population, which

amounts to 23 percent, implying that approximately one in five individuals

(among those who are employed) is a ‘working poor’. This number is threefold

the EU-25 average.32

These numbers suggest that Turkey is facing a serious welfare challenge.

Indirect welfare tools, which have enabled the governments to ‘supplement’

the earlier insufficient—albeit inegalitarian—welfare regimes, are no longer

available. The change in welfare regime in Turkey can indeed partially be

explained by this economic push and the growing severity of poverty and

social/economic vulnerability in the country. But the nature of welfare regime

31)

A. Carkoglu and M. Eder, ‘Urban Informality and Economic Vulnerability: The Case of

Turkey,’ unpublished paper (2006).

32)

F. Adaman and C. Keyder, ‘Poverty and Social Exclusion in the Slum Areas of Large Cities in

Turkey,’ research report prepared for the European Commission, Employment, Social Affairs

and Equal Opportunities (2006), 16.

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 165 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

166 M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184

change, is also path-dependent on prior institutional configurations.33 Since

the earlier welfare regime in Turkey allowed for political opportunities in the

form of agricultural subsidies and informal housing, an important question is

raised. How can the welfare regime change without losing political opportuni-

ties? And yet, welfare regime change in Turkey did occur without reducing, if

not expanding, the political power of the state.

Changing Welfare governance: Retreat or Expansion of State Power?

With their predominantly informal economies and immature welfare states,

increasingly incapable of responding to the rising demands for social services,

it is clear developing country welfare regimes diverge significantly from the

experience of mature welfare states. Turkey’s indirect welfarism described

above, based on populist agrarian subsidy programs, and endorsement/ negli-

gence of informal housing as well as over-reliance on family ties, offer just one

example of the wide variety of institutional ‘imperfect welfare mix’ in the

developing world. Further complicating the picture is the fact that the

components of this ‘welfare mix’ are in constant strain, some of the state-based

populist instruments become no longer viable under neoliberal pressures,

some of the public welfare provisions become privatized, others are subcon-

tracted and further passed on to households. How do these welfare regime

changes occur and what does this change imply in terms of the role of the state

and changing political opportunity structures?

Table 2 provides a brief overview of the welfare regime change in Turkey.

The collapse of the indirect welfare mechanisms came at the worst possible

time, when the retrenchment of the welfare state in Turkey and the gradual

withdrawal of the state from basic welfare provisions, appeared to be in full

swing in the country. Indeed, welfare reform package (Law on Social Security

and General Health Insurance) in Turkey not only increased the eligibility

requirements and premium payments for entitlements, but also ushered in

pathways for eventual privatization of healthcare.34

Privatization of social security system and the retreat of the state from

welfare provision as a whole can take a variety of forms.35 It may involve:

33)

Haggard and Kaufmann (see note 4).

34)

The law passed the parliament in 2006 and was printed in the Official Gazette on 31 May

2006, No. 5510 but was implemented in October 2008 after a series of modifications.

35)

Rudra, 2007 (see note 4).

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 166 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

Table 2. Overview of the welfare regime change in Turkey

0001165337,INDD_PG1681

Areas of social Organizational Changing eligibility PRIVATIZATION One PRIVATIZATION Two

policy restructuring requirements, access

Devolution of service Funding private actors to

provision to local admin., provide services or total

cooperation with private transfer of service provision,

sector, NGOs creating demand for private

services

Social insurance Unification of three Raising the retirement Allowing individuals to Encouraging FDI and

existing insurance age eventually to 65 buy private insurance private insurance

schemes, public for both men and and pension funds on development

contribution to the women, reduction in their own

social security system benefits

and premiums, PASG

system

Basic health care Unification and equal Universal health Encouraging private Payment to families for

access by all to all the insurance so as to hospitals and private taking care of elderly,

three health services replace Green card. pharmaceutical disabled and orphaned

associated with But except those with companies and private children, Public funding

insurance schemes, the monthly income insurance companies of private hospitals,

separate collection of of less than 1/3rd of (Basic Law on Health public funding of

social insurance and the minimum Care, 2005, land and pharmaceutical needs

M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184

(Continued)

167

167 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

0001165337,INDD_PG1681

Table 2. Overview of the welfare regime change in Turkey (Cont.,)

168

Areas of social Organizational Changing eligibility PRIVATIZATION One PRIVATIZATION Two

policy restructuring requirements, access

Devolution of service Funding private actors to

provision to local admin., provide services or total

cooperation with private transfer of service provision,

sector, NGOs creating demand for private

services

health premiums, very wage, everyone pays property of Treasury and

low state contribution, 12.5% premium, all MOH can be

marginal, SSK hospitals other coverage based transferred to corporate

merged with MOH on payment of /private bodies,

premium encouraging FDI in the

health sector

Education Free school books, Continuing with eight Encouraging private 100% Tax rebates for

increasing public year compulsory investment in education, private donors to

expenditure in education but highly public-private educations, private

education insufficient cooperation schools competing with

public schools.

Social assistance Skyrocketing of funds for Proof of poverty, NGOS, private sector Legal changes enabling

and anti- General Directorate of widows, women given involved, municipalities certain NGOS to collect

poverty Social Assistance and priority, arbitrary as ‘brokers of charity,’ donations,

M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184

Solidarity (SYDGM), definitions of the changes in municipality

elaborate but politicized poor law allowing them to

forms of social accept private donations

assistance

168 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184 169

(a) application of management techniques often observed in the private sector

such as reduction in guaranteed benefits and budget constraints, in social ser-

vices; (b) measures aimed at increasing the role of the private sector in welfare

provision which may involve tax benefits, tax concessions to donations in edu-

cation and social service; (c) establishment of clear guidelines between fund-

ing and service delivery where the public funding is still used but service

delivery is contracted to NGOs, families or private actors and finally, and;

(d) devolution and decentralization of social services where the local govern-

ments cooperate closely with various private actor and donors and solve their

‘capital’ problems so as to provide certain social services. 36

These various aspects of privatization are at work within the context of wel-

fare regime change in Turkey. What is even more interesting, however, is that

despite these privatization trends, and withdrawal of the state from social ser-

vice provision, a full-fledged ‘retreat’ of the state is not all that visible. On the

contrary, not only has the share of public expenditures for social assistance,

education and health care in GDP increased across the board, but opportunities

for using/abusing state power has actually expanded in ways that were not

possible through the earlier populist welfare instruments.

a) Privatization Cut One

Social security reform agenda in Turkey once again emerged in the context of

fiscal constraints and debt sustainability. The deficit in the social security sys-

tem has risen as high as 6 percent of the GDP in 2006, becoming the primary

motive behind the reform. The ideas such as the financial autonomy of the

hospitals, the call for the Ministry of Health to shift from service provision to

regulatory role, and the need for the reforms to be fiscally sustainable were

identified as the primary goals in World Bank’s earlier 2004 Health Transition

Project (for which the Bank loaned 49.4 million Euros) eventually made their

way to the government’s ultimate social security reform agenda.37

The main controversies of the reform package focused on pension and

healthcare. One debate was over the increase in retirement age and the increase

36)

For the discussion of how these trends operate within the European context, see U. Ascoli

and C. Ranci, eds., Dilemmas of the Welfare Mix: The New Structure of Welfare in an Era of

Privatization (New York, Boston: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2002).

37)

WorldBank,http://wwwwds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/

IB/2007/06/12/000090341_20070612135757/Rendered/PDF/40018.pdf. The specific objec-

tives were to : (i) re-structure MOH for more effective stewardship and policy making; (ii)

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 169 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

170 M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184

in the minimum number of days for which premiums are to be paid before

retirement. Not surprisingly, the package received intense criticism from labor

unions and the general public. Increased premiums and caps on existing pen-

sion payments, as well as recalculation of some of the pension payments were

particularly unpopular.

Health care was also controversial. Under the reform package, all three social

insurance funds (SSK, Bagkur and Emekli Sandıgi, as well as their correspond-

ing hospitals), were institutionally united under the management of Social

Security Institution (SSI) and linked to the Ministry of Labour and Social

Security. The idea was to increase administrative efficiency and coordinate

between highly scattered funds. The unification of the social insurance organi-

zations and their hospitals was a positive development as it allowed everyone

to have equal access to the hospitals that have hitherto been exclusive to the

respective social insurance beneficiaries.

This did, however, raise questions about creating a giant bureaucracy. When

one considers the fact that social security deficits were also largely thanks to

the use and abuse of these funds for political purposes, the degree to which

such an institution can remain autonomous from political pressures remains

to be seen. Though streamlining the social security system under one bureau-

cracy can increase ‘efficiency,’ reduce the inegalitarian hierarchies in terms of

health and pension benefits among the various funds, and can even reduce

some of the double-counting embedded in the system, it is not all that clear

whether merging bureaucracies necessarily lead to ‘lean’ governments free

from political patronage.

Perhaps the most important aspect of the social security reform with regards

to the healthcare package was the fact that it essentially pushed for the spread

of supplementary private insurance schemes, bringing an array of arrange-

ments with private hospitals to open to the general public. With the

‘Transformation in Health Program,’ the government turned public hospitals

into autonomous business institutions that competed with private hospitals

and university hospitals. As such, SSI was the chief consumer buying and

financing public and private health service. Not surprisingly, private hospitals

quickly gained the upper hand in competition and their share in Social Security

establish a universal health insurance fund; (iii) introduce family medicine as the model for the

provision of primary health care services (iv) ensure financial and managerial autonomy for all

hospitals irrespective of ownership; and (v) set up a fully computerized health and social infor-

mation system.

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 170 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184 171

health expenditures rose by 64 percent during 2002-2007 while that of state

hospitals fell by 33 percent.38 The number of private hospitals jumped from

269 to 365 in only two years, from 2005-2007.39

Many opposed such cooperation. The most vocal opposition came from the

Turkish Union of Medical Doctors, who interpreted such private-public coop-

eration as the creeping privatization of health care. Any observer of the coun-

try’s healthcare industry since the late 1990s would indeed confirm that the

private hospitals and clinics have been a booming business, and that interna-

tional insurance companies such as AIG and Allianz have flooded the market.

In fact, according to Central Bank records, foreign direct investment in health

and social work in Turkey has increased from 2 million dollars in 2002, to

35 million in 2004, and 265 million in 2006, another 177 million in 2007

and 149 million in 2008.40

If the aim of privatization of social services was to reduce the fiscal burden

of the state, however, it is clear that these trends have failed to achieve this aim.

If anything, the transfer of public funds to private agents has contributed to

the skyrocketing of public health expenditures. The public health care costs

have risen by 17 percent between 2002-2007 in fixed prices (a 200 percent

dollar increase).41

Altinok and Ucer42 argue that these rising health care costs might be thanks

to the shift from preventive care as is evident in the fall of expenditures for

people’s care, towards curative care which involves much greater consumption

of technology and medicine. As a result, medicine consumption rose by

100 percent (in Euros) between 2002 and 2007 making Turkey the country

with the highest medicine expenditures in the world as a share of the national

income. Foreign companies dominate the Turkish pharmaceutical industry

(70 percent) which suggests additional burden of current account deficits and

increases the need/dependence for foreign exchange.43

38)

Onur Hamzaoğlu and Cavit Işık Oğuz in ‘Packaging Neoliberalism: Neopopulism and the

Case of Justice and Development Party,’ Alper Yagci (MA Thesis, Department of Political Science

and International Relations, Bogazici University, Istanbul, 2009), 83.

39)

TC Sağlık Bakanlığı Tedavi Hizmetleri Genel Müdürlüğü in ibid., 11.

40)

TC Başbakanlık Müsteşarlığı Foreign Direct Investment in Turkey (Equity Capital) By

Sectors-Yearly, 2008 http://www.tcmb.gov.tr/yeni/eng.

41)

M. Altınok and A. R. and Üçer (2008), 1 www.tipkurumu.org/files/SagliktaDonusumSurecinde

SaglikHarcamalari-son.doc.

42)

Ibid.

43)

In a Sunday interview, Turkish Medical Association (TBB) ‘stated that holding the focus of

the debate on the figures of the medication consumption per capita was not healthy, and proved

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 171 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

172 M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184

Another example of privatization is found in the education of handicapped

children. In 2005, the government began giving financial assistance to

handicapped children so they might enroll in special education and rehabilita-

tion centers. Transfers for that purpose reached as high as TL 800 millions

earmarked for the year of 2009.44 Though, at first glance this step can be seen

as the state assuming responsibility for the education of handicapped children,

a closer analysis reveals that most of the handicapped children have since

enrolled in private special education centers, as the government has provided

financial aid to private institutions.

Privatization of care services, particularly for the disabled and the elderly is

yet another example. Historically, institutional care for the disabled and the

elderly has been under the responsibility of the Department of Social Services

and Protection of Children (SHÇEK). But in 2006, through a new statute,

SHCEK first allowed for private care, and through legal changes in 2007, the

government initiated a cash-transfer program for home-based disabled care.

Home-base care would then be funded through the minimum wage (approxi-

mately 300 dollars, minimum monthly wage). If home-base care was not

available, the state would have to pay the private rehabilitation center twice

the amount).45 The number of disabled people receiving home-based care

that Turkey would be the world leader if we took the ratio of the total pharmaceutical produc-

tion to the national income into account. According to the data of the TBB, the ratio of the

medication consumption to the national income in France, where the medication consumption

per capita is $391, is 1.15 percent. The ratio of the medication consumption to the national

income in Germany, where the medication consumption per capita is $308, is 0.95 percent. This

figure in Italy is $247 and the ratio is 0.82 percent, in England $250 and 0.7 percent, in Mexico,

$71 and 0.97 percent, whereas in Turkey the consumption is $93 and the ratio is 1.85 percent.

The TBB proves through these figures that Turkey is the world leader in terms of its ratio of its

medication consumption to its national income. Yagci, 2009 (see note 37).

Ali Rıza Üçer, the secretary general of the TBB, said that the increasing amount of Turkey’s medi-

cation consumption accordingly increased the dependence on imported medications. The national

pharmaceutical companies are devoured by the international monopolies and Turkey has been

reduced to a level where it is unable even to make its own vaccinations, he noted and added:

‘International companies control 70 percent of the market in Turkey. The deficit of medication

trade has exceeded $3 billion, and the ratio of the export’s ability to cover the import has dropped

to as low as 8 percent. The foreign trade deficit, increasing year by year, and our current account

deficit are to blame also in this huge trade gap that formed in the pharmaceutical commerce.’ See

Ercan Yavuz Ankara, ‘Turkey World Leader in Medication Consumption,’ Sunday Szaman, July

1, 2007, http://www.sundayszaman.com/sunday/detaylar.do?load=detay&link=1380.

44)

Yagci, 2009, 82 (see note 37).

45)

SHÇEK Genel Müdürlügğü (www.shcek.gov.tr).

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 172 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184 173

increased dramatically from 56 in 2006 to 156,806 in 2009. However, as of

April 2009, a total cash transfer to base care of the disabled has already reached

8 percent of the total SHCEK budget. As Ilkkaracan notes, a similar law is

under way regarding the elderly care.46 The state will step in to provide insti-

tutional care ‘only if there is no other alternative,’ that is if the elderly has no

relative or is rejected by the family.

Finally, the project of 100 percent support for Education (Egitime %100

Destek) led by the Ministry of Education under the leadership of the Prime

Minister in 2005, stipulated that private donors to education would get a

100 percent tax rebate on their total donations. It is yet another example of

the readiness of the state to forego some of its tax revenue in return for sharing

the responsibility of education provision with private actors.47

Toward a ‘Social Assistance’ State and a New Form of ‘Welfare

Leviathan’?

One of the striking features of Turkey’s welfare regime, in stark contrast to its

Latin American and Southern European counterparts, has been the minor role

public social assistance programs have played in overall welfare provision. A

significant reason was the continued reliance on the family. Even the 1976

Legislation on Social Disability and Old Age Pension Funds, for instance,

defined eligibility only when there was ‘no close relative’ to take care of them.48

Partly because of the ‘indirect welfarism’ described above and the reliance on

family networks, ‘social expenditure categories such as survivors’ benefits,

incapacity, family support, active labor market policies, unemployment ben-

efits and housing is very low or almost non-existent in Turkey in comparative

terms, even in relation to Mexico and Korea. It constitutes 1.3 percent of the

GDP while the OECD average is 7.9 percent and comparable figures for

Mexico and Korea are 3.1 and 1.6 percent respectively.’49

Currently, General Directorate of Social Services and Child Protection is in

charge of all the central social assistance schemes in the country. The founding

46)

Pinar Ilkkaracan, ‘Rearticulating the Relationship between Family and the State in Neoliberal

Turkey: The Case of Care Services,’ unpublished paper (2009).

47)

Eğitime %100 Destek, http://www.egitimedestek.meb.gov.tr/haber.php.

48)

Bugra and Keyder, 2006, 222 (see note 13).

49)

Ayse Bugra and Sinem Adar, ‘Social Policy Change in Countries without Mature Welfare

State: The Case of Turkey,’ New Perspectives on Turkey 38 (2008): 96.

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 173 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

174 M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184

of the directorate itself in 1986 was, as Bugra and Keyder50 rightly argue ‘an

implicit admission that the family-based solidarity may no longer be suffi-

cient.’ But institutionally, the directorate was under-funded and insignificant

for many years. The important change came with the increasing use of the

‘Fund for Encouragement of Social Cooperation and Solidarity’ (Sosyal

Yardimlasma ve Dayanismayı Tesvik Fonu, SYDTF), which later became the

General Directorate of Social Assistance and Solidarity (SYDGM), an impor-

tant independent agency. While the fund had been previously administered by

a secretariat under the Prime Ministry, in 2004, the government founded an

independent Directorate General, and passed an associated law governing the

directorate. What was most remarkable about this institutional transforma-

tion was the degree of autonomy the directorate gained as it began drawing a

significant part of its resources from the extra-budget funds. With the excep-

tion of transfers to the Ministry of National Education and Ministry of Health

for social transfers, SYDGM and its Fund Board were beyond public scrutiny

and were only accountable to the Office of Prime Ministry.51

According to Law 25665, passed in 2004, and Law 25913 in 2005, the

Fund Board and SYDGM are expected to fund and supervise a total of 973

Social Aid and Solidarity Foundations (Sosyal Yardımlaşma ve Dayanışma

Vakıfları, SYDV) located at the city and provincial level that work in quasi

autonomy from each other as well as the Directorate General. These SYDVs

could also work very closely with local private partners and develop joint proj-

ects for targeted groups. While a small part of the fund is allocated for specific

purposes, education material for children, coal, project supports while the

majority is handed over as regular periodic transfers and left for the discretion

of SYDV. Combining these figures, we see that resources allocated by SYDTF

to the SYDVs rose steadily from TL 400 million in 2004 to TL 1.25 billion in

2008.52 In 2008, the money transferred to SYDV’s paid for food for 2.1 mil-

lion families, fuel for 2.3 million families, education materials for an estimated

2 million students, and helped 28 thousand families for rebuilding their shel-

ters.53 Among the most popular programs run by SYDGM is the conditional

50)

Bugra and Keyder, 2006, 222 (see note 13).

51)

V. Yılmaz and B. Y. Çakar, ‘Türkiye’de Merkezi Devlet zerinden Yürütülen Sosyal Yardımlar

Üzerine Bilgi Notu,’ Social Policy Forum, Boğaziçi University, July 2008, http://www.spf.boun

.edu.tr/docs/calisma%20notu_SYDGM-11.08.08.pdf.

52)

Ibid., 67.

53)

See Social Assistance and Solidarity Fund, http://www.sydgm.gov.tr/tr/html/236/Aile+

Yardimlari.

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 174 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184 175

cash transfer to poor families to send their children to school. Yagci54 reports

that an estimated 2 million children saw their families receive cash, bringing

the total number of people—albeit with overlaps—to approximately 10 mil-

lion. Regardless of whether or not these assistance strategies work, to be able

to provide some sort of aid to a significant percentage of population and to

develop institutional mechanisms to ‘reach’ this many people indeed suggests

that the arguments for the ‘retreat’ of the state in the area of social assistance

are premature at best.

Despite its wide appeal, however, thanks to the discretionary nature of these

funds and the fact that they are coming primarily from extra-budget sources

beyond the scrutiny of parliament and/or international financial institutions,

the potential for patronage politics and the use of these funds for political

purposes has risen significantly. One major example was the fact that weeks

before the local elections prior to March 2009 the transfer of funds for social

purposes to the SYDV increased exponentially.55 In fact, there is a systematic

increase in total transfers starting in June 2008. Of the 2.345 billion TL that

was spent between February 2008 and 2009, approximately 800 million TL

was spent in the last three months prior to the local elections.56 The most

notorious case was when the pro-AKP governor of Tunceli saw that the local

SYDV distributed hundreds of washing machines and dishwashersin the prov-

ince, practically breaching the ban on election favors.57 Several ethnographic

studies currently underway suggest that, though definitely effective in target-

ing the poor, the degree of arbitrariness in defining the so-called ‘deserving

poor’ is considerably high among these foundations. Regardless of whether

the use of these funds for political purposes actually delivers politically, the

fact that the SYDVs could work so effectively on the ground and with such

discretionary powers, underscored the enormous potential for patronage and

politicization of the social policy framework in ways that was not possible

54)

Yagci, 2009, 83 (see note 37).

55)

According to news reports, 51 million TL has been transferred to local foundations just in

January of 2009, an amount roughly equivalent of the total social assistance budget spent during

the entire year of 2007. ‘Sosyal devlet secim oncesinde cosmos’ (Social state has gone off the roof

prior to elections), http://www.radikal.com.tr/Default.aspx?aType=RadikalDetay&ArticleID=

921498&Date=13.02.2009&CategoryID=77.

56)

Calculated from http://www.haberler.com/secim-oncesi-sosyal-yardim-ise-yaramadi-haberi/.

57)

Ferit Aslan et al., ‘Tunceli’de ‘Beyaz eşya’ yardiminda skandal,’ http://www.milliyet.com.tr/

Yasam/SonDakika.aspx?aType=SonDakika&ArticleID=1056770 (accessed on March 23, 2010).

Ironically, some of the villages of Tunceli where the washers were sent lacked roads and water to

use these machines to begin with!

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 175 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

176 M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184

before. Instead of using the rather crude and populist strategies of the earlier

era, the new institutional welfare mix and the growing importance of SYDVs,

allowed governments to extend their reach and fine-tune their political strate-

gies as they developed their ‘target population’.

Another major expansion of state power occurred in the so-called Green

Card program. Introduced in 1992, and albeit very mixed in its record and

quality of services, ‘The Green Card program’ is one of the very few mean-

tested social assistance programs. Giving access to hospitals and doctors

(though initially not medicine) to more than 12 million card holders who can

prove that they are in fact poor and in need of help as defined by law, it is

perhaps the most far-reaching as well.58 As in most social assistance schemes,

however, there were serious problems and concerns in the implementation of

the program based on arbitrariness of card distribution and subjective evalua-

tions of who constitutes the ‘deserving poor’. In some of the fieldwork that has

been done on this issue, for instance, a ‘deserving poor’ is defined as divorced,

orphaned, elderly and handicapped. A young man of working age is asked to

‘find work’ and ‘persuaded’ to find a micro credit and is hardly ever granted a

‘Green Card’.59 The emphasis on ‘work’ has not really disappeared. Similarly,

based on an ethnographic research in Southeastern city of Adiyaman, Yoltar

reports highly irregular and arbitrary distribution and implementation in the

Green Card program. Part of the problem is that, even though eligibility

requirements for a Green Card are specified by law, (those not covered by

public insurance schemes with incomes of one third of minimum wage),

establishment of income levels in highly informal labor markets has proved

very difficult. This uncertainty, has in turn, created enormous room for discre-

tion and interpretation of the laws by local officials fueling patronage net-

works and clientelism.60 Who gets to define the ‘deserving poor’ and how

58)

Bogazici Universitesi, Social Policy Forum.

59)

Ayse Bugra and Çağlar Keyder, ‘Kent Nufüsünün en yoksul kesiminin istihdam yapısı ve

geçinme yöntemleri’ (‘The employment structure and the survival strategies of the urban poor’)

(Unpublished TUBITAK report, 2008), 21.

60)

See ibid., 774. Yoltar describes the following episode to demonstrate the arbitrariness and the

dangers of this local discretion: During my first visit to Adıyaman in 2004, a co-administrator

from the Directorate of Health-Care shared with us a very peculiar story as to why they decided

to (arbitrarily) terminate the Green Cards issued for citizens of Alevite conviction. He told us

that at first Alevites were being granted Green Cards; but then ‘they started to convert to

Christianity’. Apparently when the upper level bureaucracy demanded a reduction in the

number of Green Cards in circulation, local Green Card officials chose to terminate the Green

Cards of certain Alevite individuals belonging to communities in several villages that were

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 176 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184 177

these Green Cards will be distributed then becomes easily politicized, extend-

ing the political power of the state.

According to Altinok and Ucer,61 Green Card expenditures have increased

18 fold since 2000, when 10 million people had them. This number increased

to 13 million in 2002, but dropped to 6.7 million in 2004 before increasing

once again in 2007 to 10.8 million and skyrocketing to 14.5 million prior to

2007 national elections. In 2008, however, it dropped again to 9.4 million,

due to the Green Card cancellations after the national elections. Once again,

the wide fluctuation in these numbers suggests that the distribution of these

Green Cards was indeed very politicized, and that there was ample room for

patronage politics. As part of the welfare reform package, the government also

proposed a universal health care scheme that would replace the Green Card,

The government would pay for health insurance for all those lacking insurance

and with income levels below one third of the minimum wage. It is highly

unlikely however that this new scheme, despite its mission of universal cover-

age, will be free from political influence.

Privatization Take Two: Other Actors in the ‘Welfare Mix,’

Municipalities as Charity Brokers, New Public-Private Cooperation

Schemes

What was also remarkable since 2003 was the increasing visibility of the

municipalities in the social assistance scheme. In 2005, with the laws concern-

ing provincial administration and greater municipalities, local municipalities

assumed greater responsibilities in social assistance. Metropolitan Municipality

Law (No. 5216), Provincial Special Administrations Law (No. 5302), Local

Administration Unions Law (No. 5355), Municipalities Law (No. 5393) were

subject to these rumors of conversion. Of course, according to the Green Card legislation, all

citizens—regardless of religious belief or ethnicity—who fit the Scheme’s poverty criteria would

be eligible for a Green Card. However, in the absence of legible guiding criteria, local officials are

free to take advantage of their abundant discretionary powers to make termination decisions

based on their own under- standings of who is a ‘fine’ citizen deserving of the state’s compassion.

The same co- administrator further shared with us that ‘we give these people Green Cards. But

then when they go and convert to Christianity, it is us who get into trouble. They ask us: why

did you give Green Cards to these people?’ This is an example of how the state delineates through

local practices the category of citizen and its margins.’

61)

Altınok and Üçer, 4 (see note 41).

0001165337,INDD_PG1681 177 4/13/2010 2:19:33 PM

178 M.Eder / Middle East Law and Governance 2 (2010) 152–184

among those passed since 2004. Candan and Kolluoğlu’s62 summary of the

effect of these laws provides a useful overview: ‘Municipality laws introduced

in 2004 and 2005…made the already influential office of the mayor even

more powerful. These new powers include: (1) broadening the physical space

under the control and jurisdiction of the greater municipality; (2) increasing

its power and authority in development (imar), control and coordination of

district municipalities; (3) making it easier for greater municipalities to estab-

lish, and/or create partnerships and collaborate with private companies;

(4) defining new responsibilities of the municipality in dealing with ‘natural

disasters;’ and (5) outlining the first legal framework for ‘urban transforma-

tion,’ by giving municipalities the authority to designate, plan and implement

‘urban transformation’ areas ‘and projects’.

Not surprisingly, the enhanced power of the municipalities created ample

room for patronage politics, as they were allowed to use private sector and/or

wealthy organizations for various services and funding. Municipalities have

thus become very visible by way of organizing soup kitchens for the poor,

building giant food tents for iftar meals during the month of Ramadan, and,