Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Choice of Law Rules USA 2008

Uploaded by

Kofi BrobbeyCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Choice of Law Rules USA 2008

Uploaded by

Kofi BrobbeyCopyright:

Available Formats

Choice of Law in the American Courts in 2008: Twenty-Second Annual Survey

Author(s): SYMEON C. SYMEONIDES

Source: The American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 57, No. 2 (SPRING 2009), pp. 269-329

Published by: American Society of Comparative Law

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25652644 .

Accessed: 09/10/2013 14:07

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Society of Comparative Law is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

The American Journal of Comparative Law.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SYMEON C. SYMEONIDES*

Choice of Law in the American Courts in 2008:

Twenty-Second Annual Survey

Table of Contents

I. Introduction. 270

II. Methodology. 272

A. Torts. 272

B. Contracts. 275

C. The Methodological Table. 278

III. Torts . 280

A. Employment Injuries. 280

B. Common-Domicile Cases. 283

C. Cross-Border Torts. 288

D. Other Torts. 291

IV. Products Liability. 292

A. Foreign Plaintiffs and Forum Non Conveniens. 292

B. Inverse Conflicts. 296

C. Direct Conflicts. 299

V. Contracts . 301

A. Contracts with Choice-of-Law Clauses. 301

B. Choice of an Invalidating Law. 303

C. Contracts Without Choice-of-Law Clauses . 304

D. Insurance Contracts. 306

1. Automobile Insurance. 306

2. Other Insurance Contracts. 307

VI. Domestic Relations . 310

A. Marriage. 310

B. Divorce, Marital Property and Alimony. 312

C. Adoption, Child Custody, and Child Support. 314

VII. Statutes of Limitation. 315

VIII. Recognition of Judgments. 315

IX. U.S. Law in the International Arena. 317

A. The Extraterritorial Reach of the U.S.

Constitution. 317

1. Habeas Corpus. 317

* Dean & Alex L. Parks

Distinguished Professor ofLaw, Willamette University

College of Law; LL.B. (Priv. L.), LL.B. (Publ. L.), Aristotelian of Thes

University

saloniki; LL.M., S.J.D., Harvard Law School.

269

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

270 the american journal of comparative law [Vol. 57

2. Fourth Amendment. 320

3. Fifth Amendment. 320

B. Application ofFederal Law toCases with Foreign

Elements. 322

1. The Alien Tort Statute. 322

2. Other Statutes. 325

C. The Domestic Effect oflCJ Judgments. 326

D. Jurisdiction and Forum Non Conveniens. 328

I. Introduction

This is the Twenty-Second Annual Survey ofAmerican Choice-of

Law Cases.1 It is written at the request of the Association of Ameri

can Law Schools Section on Conflict of Laws2 and is intended as a

service to fellow teachers and students of conflicts law, both within

and outside the United States. Its purpose remains the same as it has

been from the beginning?to inform, rather than to advocate.

The Survey covers cases decided by American state and federal

appellate courts from January 1 to December 31, 2008, and reported

1. The previous twenty-one surveys are, in chronological order: P. John Kozyris,

Choice of Law in the American Courts in 1987: An Overview, 36 Am. J. Comp. L. 547

(1988); Symeon C. Symeonides, Choice ofLaw in theAmerican Courts in 1988, 37 Am.

J. Comp. L. 457 (1989); P. John Kozyris & Symeon C. Symeonides, Choice ofLaw in

the American Courts in 1989: An Overview, 38 Am. J. Comp. L. 601 (1990); Larry

Kramer, Choice of Law in the American Courts in 1990: Trends and Developments, 39

Am. J. Comp. L. 465 (1991); Michael E. Solimine, Choice of Law in the American

Courts in 1991, 40 Am. J. Comp. L. 951 (1992); Patrick J. Borchers, Choice ofLaw in

the American Courts in 1992: Observations and Reflections, 42 Am. J. Comp. L. 125

(1994); Symeon C. Symeonides, Choice ofLaw in theAmerican Courts in 1993 (and in

the Six Previous Years), 42 Am. J. Comp. L. 599 (1994); Symeon C. Symeonides, Choice

ofLaw in theAmerican Courts in 1994: A View 'From theTrenches/ 43 Am. J. Comp.

L. 1 (1995); Symeon C. Symeonides, Choice ofLaw in theAmerican Courts in 1995: A

Year inReview, 44 Am. J. Comp. L. 181 (1996); Symeon C. Symeonides, Choice ofLaw

in theAmerican Courts in 1996: Tenth Annual Survey, 45 Am. J. Comp. L. 447 (1997);

Symeon C. Symeonides, Choice of Law in theAmerican Courts in 1997, 46 Am. J.

Comp. L 233 (1998); Symeon C. Symeonides, Choice ofLaw in theAmerican Courts in

1998: TwelfthAnnual Survey, 47 Am. J. Comp. L. 327 (1999); Symeon C. Symeonides,

Choice ofLaw in theAmerican Courts in 1999: One More Year, 48 Am. J. Comp. L. 143

(2000); Symeon C. Symeonides, Choice ofLaw in theAmerican Courts in 2000: As the

Century Turns, 49 Am. J. Comp. L. 1 (2001); Symeon C. Symeonides, Choice ofLaw in

theAmerican Courts in 2001: Fifteenth Annual Survey, 50 Am. J. Comp. L. 1 (2002);

Symeon C. Symeonides, Choice ofLaw in theAmerican Courts in 2002: Sixteenth An

nual Survey, 51 Am. J. Comp. L. 1 (2003); Symeon C. Symeonides, Choice ofLaw in the

American Courts in 2003: Seventeenth Annual Survey, 52 Am. J. Comp. L. 9 (2004);

Symeon C. Symeonides, Choice of Law in theAmerican Courts in 2004: Eighteenth

Annual Survey, 52 Am. J. Comp. L. 919 (2004); Symeon C. Symeonides, Choice ofLaw

in theAmerican Courts in 2005: Nineteenth Annual Survey, 53 Am. J. Comp. L. 559

(2005); Symeon C. Symeonides, Choice ofLaw in theAmerican Courts in 2006: Twen

tiethAnnual Survey, 54 Am. J. Comp. L. 697 (2006); and Symeon C. Symeonides,

Choice ofLaw in theAmerican Courts in2007: Twenty-FirstAnnual Survey, 56 Am. J.

Comp. L. 243 (2008). Hereinafter, these Surveys are referred to only by the author's

name and the survey year.

2. This Survey does not reflect the views of the Association ofAmerican Law

Schools or its Section on Conflict of Laws.

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2009] CHOICE OF LAW IN THE AMERICAN COURTS IN 2008 271

during the same period. Of the 3,533 conflicts cases meeting both of

these parameters,3 the Survey focuses on those of the 1,194 appellate

cases that may add something new to the development or under

standing of conflicts law and particularly choice of law.

The following are among the cases discussed in this Survey:

Two U.S. Supreme Court cases and several intermediate court

cases delineating the extraterritorial reach of the Constitution and

federal statutes, and one Supreme Court case on the domestic ef

fect of a judgment of the International Court of Justice (Part IX);

A New Jersey Supreme Court case abandoning Currie's interest

analysis in tort conflicts and adopting the Restatement (Second),

and a New Mexico Supreme Court case abandoning the traditional

approach in contract conflicts (but only in class actions) and adopt

ing the "false conflictdoctrine" of the Restatement (Second) (Part

II);

Several cases applying (and one not applying) the law of the par

ties' common domicile to cases arising from torts occurring in

another state (III.B);

Several cases involving cross-border torts and applying the law of

whichever of the two states (conduct or injury) favors the plaintiff

(III.C);

Several product liability cases granting forum non conveniens dis

missals in favor of alternative fora in foreign countries, and those

countries' responses by enacting "blocking statutes" (IV.A);

Several cases refusing to enforce clauses precluding class-action or

class-arbitration, and one case applying a contractually chosen law

that invalidated a critical part of the contract (V.A-B);

Three cases illustrating the race to the courthouse between insur

ers and their insureds (V.D.2);

Several New York cases recognizing Canadian and Massachusetts

same-sex marriages, and a case refusing to recognize a Pakistani

talaq (unilateral, non-judicial divorce) (VI.A-B); and

One case refusing to recognize a foreign judgment that conflicted

with a previous judgment fromanother country,and another case

3. Unlike previous years, this Survey covers only appellate cases. These cases

have been identified by searching Westlaw's 2008 "Allcases" database with various

queries, as well as with all the key numbers thatWestlaw uses in placing cases into

its "Conflict ofLaws" database. Of the 3,533 cases, 890 were decided by state appel

late courts, 304 by federal appellate courts and 2,284 by federal courts. Based on data

fromprevious years, it is expected that,when the remaining 2008 cases are posted in

Westlaw in the firstweeks of 2009, the total number of 2008 conflict cases will ap

proach 4,000.

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

272 the american journal of comparative law [Vol. 57

resolving an ambiguity in the Uniform Foreign Money-Judgments

Recognition Act (VIII).

II. Methodology

A. Torts

In 1967, New Jersey was one of the first states to abandon the

traditional lex loci delicti rule and to adopt Brainerd Currie's interest

analysis.4 New Jersey continued to follow that approach?albeit with

the weighing of state interests5 that Currie decried?even though all

but two other jurisdictions had switched to another modern ap

proach. The other two jurisdictions are California, which in true

conflicts complements interest analysis with comparative impair

ment, and the District of Columbia, which also weighs state interests

in true conflicts. In two of its recent and rather poorly reasoned deci

sions, the New Jersey Supreme Court also relied on the Restatement

(Second), albeit in a rather secondary fashion.6 In the 2008 case P. V.

v. Camp Jaycee,7 the court officially completed its switch to the Re

statement (Second).8

Aside from the outcome, Camp Jaycee was eerily similar to the

famous New York case Schultz v. Boy Scouts of America, Inc.,9 in

which the New York Court of Appeals applied New Jersey's charita

ble immunity rule and barred an action between New Jersey

domiciliaries arising from sexual misconduct in New York. The plain

tiff in Camp Jaycee was a twenty-year-old mentally challenged New

Jersey domiciliary who attended a summer camp in Pennsylvania

run by defendant Camp Jaycee, a New Jersey charitable corporation.

While at the camp, plaintiff was allegedly sexually assaulted by an

other summer camp attendee, causing the plaintiff to suffer personal

injuries. The plaintiffs suit against Camp Jaycee was barred by New

Jersey's charitable immunity rule but not by Pennsylvania law. The

4. See Mellk v. Sarahson, 229 A.2d 625 (N.J. 1967).

5. See, e.g., Eger v. E.I. Du Pont De Nemours Co., 539 A.2d 1213 (N.J. 1988).

6. See Erny v. Estate ofMerola, 792 A.2d 1208 (N.J. 2002) (discussed in Symeo

nides, 2002 Survey 15-17; applying New York's pro-plaintiffjoint and several liability

rule to a case arising out of a New Jersey accident involving a New Jersey plaintiff

and New York defendants); Fu v. Fu,733 A.2d 1133 (N.J. 1999) (discussed in Symeo

nides, 1999 Survey 153-154; applying New York's pro-plaintiff car-owner liability

statute to a case arising out of a New York accident caused by a car rented in New

from a Pennsylvania car rental company and injuring a New Jersey plaintiff).

Jersey

7. 962 A.2d 453 (N.J. 2008).

8. For other 2008 New Jersey cases decided under interest analysis before Camp

see Dolan v. Sea Transfer Corp., 942 A.2d 29 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. 2008),

Jaycee,

cert, denied, 950 A.2d 907 (N.J. May 16, 2008) (discussed infra at III.C); Varo v.

Owens-Illinois, Inc., 948 A.2d 673 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. 2008) (discussed infra at

IV.A); Smith v. Alza Corp., 948 A.2d 686 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. 2008) (discussed

infra at IV.D); Thabault v. Chait, 541 F.3d 512 (3d Cir. 2008) (decided under New

Jersey conflicts law).

9. 480 N.E.2d 679 (N.Y. 1985).

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2009] CHOICE OF LAW IN THE AMERICAN COURTS IN 2008 2 73

trial court dismissed the suit under New Jersey law, concluding that

New Jersey's interests in protecting New Jersey charities outweighed

Pennsylvania's interest in subjecting charities to the same tort rules

as other private entities. The Appellate Division reversed, finding

that Pennsylvania's interest in regulating the conduct of people act

ing within its territory outweighed New Jersey's interest in

immunizing its charitable corporations.10 Applying the Restatement

(Second), the New Jersey Supreme Court affirmed in a four-to-three

decision.

The court began its discussion with section 146 of the Restate

ment, which provides that, in personal injury actions, the law of the

place of conduct and injury governs "unless, with respect to the par

ticular issue, some other state has a more significant relationship

under the principles stated in ? 6."11 The court characterized this as

an "intuitively correct principle" because "the state in which the in

jury occurs is likely to have the predominant, if not exclusive,

relationship to the parties and issues in the litigation."12 After dis

cussing the contacts listed in section 145, the court concluded that

the presumption of section 146 was not overcome. Both the conduct

and the injury occurred in Pennsylvania, and the parties' presence

there was prolonged and not fortuitous. Additionally, said the court,

the parties' relationship was centered there because? although both

parties were New Jersey domiciliaries? plaintiff "chose to attend

camp in Pennsylvania" and the defendant was incorporated "for the

of a camp . . . in . . .

primary purpose running solely Pennsylvania"

and that state was "the principal place of the business for which it

was incorporated."13

The court then turned to the policy factors of section 6 of the Re

statement (Second), focusing primarily on the interests of the two

states. The court noted New Jersey's interest in protecting its chari

table corporations through its "post-event loss-allocation policy" of

charitable immunity.14 However, the court concluded that this inter

est was weakened by the fact that the defendant corporation chose to

operate outside New Jersey and caused the injury outside New

Jersey.15

10. The Appellate Division's opinion is discussed in Symeonides, 2007 Survey

258-60.

11. Restatement (Second) of Conflict of Laws ?146 (1971).

12. Camp Jaycee, 962 A.2d at 461.

13. Id. at 462 (italics in original). See also id. ("Even if [plaintiff]signed on as a

camper administrative office in New ... it is of little

through Camp Jaycee's Jersey

consequence because this is not a contracts case. Rather, it is a tort action and, from

that perspective, there is no question that [plaintiffs]relationship with Camp Jaycee

was centered on her camp experience in . . .

Pennsylvania.")

14. Id. at 463.

15. See id. at 466. as here, . . . the to perform its pri

([W]here, corporation opts

mary charitable acts outside the state, the strength of that contact is diluted. Indeed,

immunity laws are designed to encourage persons to engage in the particular conduct

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

274 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE LAW [Vol. 57

In contrast, the court found Pennsylvania's interest to be very

strong. Following Justice Jasen's dissenting opinion in Schultz,16 the

court characterized Pennsylvania's non-immunity rule as conduct

regulating: "[W]hen a state decides to abrogate its charitable immu

nity law, it typically does so with the intention of insuring due

care."17 In light of defendant's "continuous and deliberate presence

. . . and in Pennsylvania," the court reasoned, Penn

activity"

sylvania's "interest in conduct-regulation" was particularly strong:

If Pennsylvania's tort law is to have any deterrent impact

and protect other campers from the type of harm inflicted

upon [plaintiff],itmust be applied in situations where tort

feasors repeatedly perform their tasks within the state, re

gardless of the home state of the campers. Indeed, there is no

way for a state to "make its territory safe for residents with

out making it safe for visitors too."18

The court compared the interests of the two states in light of

their contacts and concluded that New Jersey's interests should yield:

Pennsylvania's policy of conduct-regulation and recompense

is deeply intertwined with the various Pennsylvania con

tacts in the case. On the contrary, New Jersey's loss

allocation policy does not warrant the assignment of priority

to the parties' domicile in New Jersey in connection with ac

tivities outside the state's borders.19

The court concluded:

[N] either the [section 145] contacts themselves nor the sec

tion 6 considerations support the conclusion that New Jersey

has a more significant relationship to the case than Penn

sylvania. In fact, the converse is true. Although we recognize

the vitality of our own policy of immunizing charities, in this

case, itmust yield to the presumption favoringapplication of

Pennsylvania law, which has not been overcome.20

within the state.Where defendant's conduct takes place in another state, the immu

nity goals are diminished.").

16. The court found that this case was "entirely distinct fromSchultz insofar as

the Boy Scout troop in Schultz was chartered in New Jersey and the assault took

place on an outing toNew York .... In fact, some assaults inSchultz also took place

inNew Jersey. Here, the camp was a fixture in Pennsylvania and the assaults and

the injury occurred there." Id. at 466 n.8.

17. Id. at 464.

18. Id. at 466 (quoting Louise Weinberg, Against Comity, 80 Geo. L.J. 53, 89

(1991)).

19. Id. at 468.

20. Id.

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2009] CHOICE OF LAW IN THE AMERICAN COURTS IN 2008 275

Three members of the court dissented, criticizing the majority

both for adopting the Restatement (Second) and for applying Penn

sylvania law.

Camp Jaycee is the third recent case in which the New Jersey

Supreme Court has applied the pro-plaintiff law of another state for

the benefit of a New Jersey plaintiff.This time, at least the plaintiffs

recovery came from another New Jersey domiciliary. In the other two

cases, recovery came at the expense of a non-forum defendant.21 In

three other cases, the same court extended the benefit of its pro

plaintiff law to foreign plaintiffs at the expense of domestic defend

ants;22 in two cases, it denied that benefit;23 and in one case, the

court applied another state's pro-defendant law for the benefit of a

non-forum defendant at the expense of a forum plaintiff.24 None of

these cases involved the common-domicile pattern. In the two cases

that did involve that pattern, the court applied the law of the com

mon domicile not only when it favored the plaintiff,25 but (unlike

Camp Jaycee) also when it favored the defendant.26

B. Contracts

New

Mexico has been one of ten states to follow the traditional

methodology in tort conflicts and one of twelve states that has done

likewise in contract conflicts.27 The New Mexico Supreme Court had

displayed an occasional willingness to consult the Restatement (Sec

ond), but, prior to 2008, the court had not encountered an opportunity

21. See Erny v. Estate ofMerola, 792 A.2d 1208 (N.J. 2002) and Fu v. Fu, 733

A.2d 1133 (N.J. 1999), supra note 6.

22. See Pfau v. Trent Aluminum Co., 263 A.2d 129 (N.J. 1970) (refusing to apply

Iowa's guest statute and allowing recovery under New Jersey's pro-plaintiff law in a

case arising out of an Iowa accident involving a New Jersey defendant and a Connect

icut plaintiff); D'Agostino v. Johnson & Johnson, Inc. 628 A.2d 305 (N.J. 1993)

(applying New Jersey's pro-plaintiff law to a case of retaliatory discharge of a Swiss

employee from a Swiss subsidiary of a New Jersey corporation; the discharge was

orchestrated by executives of the parent corporation in New Jersey); and Gantes v.

Kason Corporation, 679 A.2d 106 (N.J. 1996) (applying New Jersey's pro-plaintiff

statute of limitation to a product liability action filed against a New Jerseymanufac

turer by the family of a Georgia woman killed by the product inGeorgia).

23. See Heavner v. Uniroyal, Inc., 305 A.2d 412 (N.J. 1973) (applyingNorth Caro

lina's statute of limitation to bar a products liability action by a North Carolina

plaintiff against a New Jerseymanufacturer and arising out of injury inNorth Caro

lina); Rowe v. Hoffman-La Roche, Inc., 917 A.2d 767 (N.J. 2007) (discussed in

Symeonides, 2007 Survey 273-78).

24. Eger v. E.I. Du Pont De Nemours Co. 539 A.2d 1213 (N.J. 1988) (applying

South Carolina's workers' compensation law,which immunized a South Carolina con

tractor from suit filedby a New Jersey employee of a New Jersey subcontractor, in a

case arising out of South Carolina injury).

25. See Mellk v. Sarahson, 229 A.2d 625 (N.J. 1967) (refusing to apply Ohio's

guest statute in a case arising from an Ohio accident involvingNew Jersey parties).

26. See Veazey v. Doremus, 510 A.2d 1187 (N.J. 1986) (applying Florida inter

spousal immunity rule, rather than New Jersey non-immunity rule, to a case arising

from a New Jersey accident involving Florida spouses).

27. For a list of the lex loci delicti and lex loci contractus states, see infra II.C.

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

276 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE LAW [Vol. 57

to revisit the matter since the mid-1990s.28 In Ferrell v. Allstate In

surance Company,29 a class-action case, the court had a limited

opportunity to consider its choice-of-law methodology in contract con

flicts, and the court made the most of it.

Ferrell was a breach-of-contract class action30 filed against All

state Insurance Company by its insureds, who bought their policies

(andwere domiciled) in fifteen states.31After findingthat the laws of

thirteen of the fifteen states were substantially similar to New Mex

ico law, the district court certified the class under New Mexico law for

the plaintiffs from those thirteen states. The Court of Appeals, how

ever, decertified the class, reasoning that the laws of the thirteen

states "potentially" conflicted due to ambiguities and lack of appellate

precedents in some of those states. Because of these potential con

flicts, New Mexico law could not be applied to the claims of all

plaintiffs. Instead, under New Mexico's lex loci contractus rule, the

court had to apply the laws of each state in which the insurance con

tracts were made, thus rendering the class unmanageable.

The New Mexico Supreme Court reversed. The court approved

the lower court's use of "the 'false conflict' doctrine"32 as the initial

step for deciding whether to certify a class. However, the supreme

court opted instead to use the terms "non-conflict" and "actual con

flict" in order to avoid any confusion from the dual meaning of the

28. For torts, see Torres v. State, 894 P.2d 386 (N.M. 1995) the

(acknowledging

court's past adherence to the lex loci delicti rule, but refusing to apply it and instead

using a reasoning that approximated a modern policy analysis); Estate of Gilmore,

946 P. 2d 1130 (N.M. Ct. App. 1997) (acknowledging that theNew Mexico Supreme

Court "ha[d] not embraced the Restatement Second ... in either tort or contract," id.

at 1136, but relying heavily on the Restatement (Second) and concluding that "policy

considerations may override the place-of-the-wrong rule." Id. at 1135). For contracts,

see State Farm Mut. Ins. Co. v. Conyers, 784 P.2d 986 (N.M. 1989). But see Shope v.

State Farm Ins. Co., 955 P.2d 515 (N.M. 1996) (applying the lex loci contractus with

out discussion); Reagan v. McGee Drilling Corp., 933 P.2d 867 (N.M. Ct. App. 1997),

cert,denied, 932 P.2d 498 (applying alternatively the public policy exception to the lex

loci and the Restatement (Second)).

29. 188 P.3d 1156 (N.M. 2008).

30. For other state supreme court cases affirming class certifications under the

law of the forum, see FirstPlus Home Loan Owner 1997-1 v. Bryant,_S.W.3d_,

2008 WL 518226 (Ark. Feb. 28, 2008), reh'g denied (Apr. 10, 2008); General Motors

Corp. v. Bryant,_S.W.3d_, 2008 WL 2447477 (Ark. June 19, 2008). For a case

affirming class certification under the forum's statute of limitations and the substan

tive law of another state, see Masquat v. DaimlerChrysler Corp., 195 P.3d 48 (Okla.

2008), reh'g denied (Oct. 27, 2008). For a case affirminga denial of class certification

after finding forum law inapplicable, see Landau v. CNA Financial Corp., 886 N.E.2d

405 (111.App. 1st Dist. 2008), appeal denied, 897 N.E.2d 253 (111.2008). For a case

dismissing a nationwide class action for lack of standing under forum law, without a

choice-of-law analysis, see DaimlerChrysler Corp. v. Inman, 252 S.W.3d 299 (Tex.

2008).

31. The plaintiffs contended thatAllstate breached its contractswith plaintiffsby

failing to include installment fees that are charged when an insured opts to pay the

premium in monthly installments rather than in one lump sum.

32. See Ferrell, 188 P.3d at 1164.

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2009] CHOICE OF LAW IN THE AMERICAN COURTS IN 2008 277

term "false conflict" and any association with Currie's interest

analysis.33

The court noted that, under Phillips Petroleum Co. v. Shutts34

and Sun Oil Co. v. Wortman35 the forum may constitutionally apply

its own law to the claims of all plaintiffs in a multistate class action if

there is no actual conflict between that law and the laws of the other

states involved. The court held that, although the class plaintiffs bear

the initial burden of showing that the various states' laws are sub

stantially similar (a "non-conflict"), the plaintiffs should not be

required to prove the absence of an actual conflict in order to obtain

class certification. Instead, the party opposing certification must es

tablish the existence of an actual, and not merely a hypothetical,

conflict. Finding in this case that the class plaintiffs had carried the

burden of showing a non-conflict but the defendant did not carry its

burden of showing an actual conflict, the court reinstated the class

certification and upheld the district court's decision to apply New

Mexico law.

The supreme court acknowledged that the adoption of the "actual

conflict doctrine" represented a "divergence" from the First Restate

ment, which, as the court correctly noted, "does not contemplate a

comparison of the laws of the states involved."36 However, reasoning

that such a divergence was dictated by New Mexico's class action

rule,37 the court approved this doctrine "for the benefit of our class

action jurisprudence."38

The court could have stopped there, but it did not. Instead, the

court criticized the First Restatement (especially its jurisdiction-se

lecting nature) in a way that went beyond the needs of the particular

case. Moreover, the court went out of its way to praise the Restate

ment (Second)?even though the "actual conflict doctrine," which the

court adopted, is a common feature of all modern choice-of-law meth

odologies, not just the Restatement (Second). After noting that

twenty-four other states have rejected the First Restatement and

adopted the Second Restatement, the court concluded that

33. See id. at 1164 n.2. The first meaning of false conflict, used in Currie's interest

analysis, describes cases in which only one of the involved states has an interest in

applying its law. The second meaning describes cases in which the laws of the in

volved states produce the same outcome. The Ferrell court adopted the second

meaning, calling it "non-conflict."

34. 472 U.S. 797 (1985).

35. 486 U.S. 717 (1988).

36. Id. at 1171.

37. See id. ("If a court finds that the laws of the relevant states are similar enough

to meet the predominance requirement, but then has to apply the laws of the state

where the insured entered into the contract, the district court's analysis regarding

predominance would have been in vain.")

38. Id.

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

278 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE LAW [Vol. 57

the rigidity of the Restatement (First) is particularly ill

suited for the complexities present in multi-state class ac

tions. It does not allow a court to consider the competing

policies of the states implicated by the suit.We conclude that

the Restatement (Second) is a more appropriate approach for

multi-state contract class actions.39

As the last quoted sentence indicates, the court's adoption of the

Restatement (Second) is limited to "contract class actions." Read in

the narrow context of the Ferrell case, this means at a minimum that

New Mexico will use the Restatement in contract class actions in

which the laws of the involved states would produce the same out

come (i.e., false conflicts). This leaves several methodological

questions unanswered, including whether the court will also rely on

the Restatement (Second) in: (1) contract class actions inwhich the

laws of the involved states would produce different outcomes ("actual

conflicts");40 or (2) individual contract actions which present a false

conflict (why not?) or an actual conflict. Indeed, the logic of Ferrell

would also apply to all cases that present false conflicts, be they (a)

individual contract actions, (b) tort class actions, or (c) individual tort

actions. In fact, the New Mexico Court ofAppeals has already applied

the "false conflict doctrine" to an individual contract action.41 Even

so, it is better to err on the side of caution and keep New Mexico in

the traditional column for both tort and contract conflicts but add an

asterisk for class actions.

C. The Methodological Table

New Jersey's abandonment of interest analysis in favor of the

Restatement (Second) causes a minor shift in the methodological

count, with the interest analysis column dropping to two jurisdic

tions?California and the District of Columbia. In light of the pivotal

role that interest analysis played in the choice-of-law revolution, this

is a remarkable development. In fact, a more literal classification

might place even these two jurisdictions elsewhere, insofar as they

engage in the very weighing of state interests that Currie proscribed.

District of Columbia courts weigh interests openly and unapologeti

39. Id. at 1173 (footnoteomitted).

40. In Fiser v. Dell Computer Corp., 188 P.3d 1215 (N.M. 2008), which was de

cided after Ferrell and involved a contract containing a choice-of-law

twenty days

clause and a clause class actions, the court did not mention the Restate

prohibiting

ment or Ferrell. Fiser is discussed infra at V.A.

41. See Fowler Brothers, Inc. v. Bounds, 188 P.3d 1261 (N.M. Ct. App. 2008) (dis

an action filed by an Arizona sub-contractor against a New Mexico contractor

missing

arising out of an Arizona construction project because the laws of both states required

a contractor's licence, which plaintiff did not have).

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2009] choice of law in the american courts in 2008 2 79

cally,42 while California courts prefer to weigh not the interests

themselves but the impairment thatwould result from subordinating

those interests.43 Thus, a more technical classification might move

these jurisdictions to differentcolumns, leaving completely blank the

interest-analysis column four decades after Currie's death.

However, this should not suggest that Currie's influence has dis

appeared. First, an interest analysis traceable to Currie forms the

core of most of the "combined modern" approaches followed in the

states listed in that last column of the table below. Second, interest

analysis is oftenheavily employed in states that generally follow the

Second Restatement, especially in cases in which the factual contacts

are evenly divided between the involved states.44 Thus, in the same

manner that the high numerical following of the Restatement (Sec

ond) tends to inflate its actual importance in deciding cases, the low

numerical following of Currie's original approach tends to undervalue

the importance of this approach in influencing judicial decisions.

With this and other caveats and qualifications detailed in the

Surveys of previous years, here is the updated methodological table.

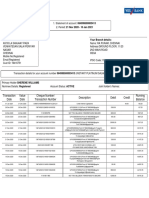

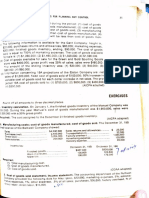

Table 1. Alphabetical List of States and Choice-of-Law

Methodologies Followed

Signif. Restate- Interest Lex Better Combined

States Traditional Contacts ment 2d Analysis Fori Law Modern

Alabama_T+C_

Alaska_T+C_

Arizona T+C

Arkansas C T

California_T_C

Colorado_T+C_

Connecticut_T+ C?_

Delaware_T+C_

Dist. of

Columbia_T_C

Florida_C_T_ZZZIH_

Georgia_T+C_

Hawaii_T+C

Idaho_T+C_

Illinois_T+C

Indiana_T+C_

T+C

Iowa_

Kansas_T+C_

T

Kentucky_C

42. See, e.g., Kaiser-Georgetown Comm. Health Plan, Inc. v. Stutsman, 491 A.2d

502 (D.C. App. 1985).

43. See, e.g., Kearney v. Salomon Smith Inc., 137 P.3d 914 (Cal.

Barney, 2006),

discussed in Symeonides, 2007 Survey 243, 249-52.

44. See Symeon C. Symeonides, The Judicial Acceptance of theSecond Conflicts

Restatement: A Mixed Blessing, 56 Md. L. Rev. 1248, 1262-63 (1997).

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

280 the american journal of comparative law [Vol. 57

Signif. Restate- Interest Lex Better Combined

Contacts ment 2d Analysis Fori Law Modern

States_Traditional

Louisiana T+C

Maine_T+C_

Maryland_T+C_

Massachusetts T+C

Michigan_C_T_

Minnesota T+C

Mississippi T+C

Missouri T+C

Montana_T+C_

Nebraska_T+C_

Nevada_C_T_

New

Hampshire_C_T_

New ~

Jersey_T_C

New Mexico

T+C*45_

New

York_T+C

N.

Carolina_T_C_

North

Dakota_T_C

Ohio_T+C_

Oklahoma_C_T_

Oregon_T+C

T+C

Pennsylvania_

Puerto

Rico_T+C_

Rhode

Island_C_T_

S.

Carolina_T+C_

S.

Dakota_T+C_

Tennessee

C_T_

Texas_T+C_

Utah_T+C_

Vermont_T+C_

Virginia_T+C_

Washington_T+C_

West

Virginia_T_C_

Wisconsin_T+C_

Wyoming_T+C_

TOTAL 52 Torts 10 Torts 3 Torts 24 Torts 2 Torts 2 Torts 5 Torts 6

0 |Contr. 2 10

_I

Contr. 12

|Contr. 5 |Contr. 23 |Contr.

0

|Contr. |Contr.

T = Torts C = Contracts

III. Torts

A. Employment Injuries

Jaiguay v. Vasquez46 was a tort action filed in Connecticut by the

estate of a New York domiciliarywho was killed in a trafficaccident

while riding as a passenger (with six others) in a pickup truck driven

by his co-employee. The accident occurred while the truck was briefly

45. See Ferrell v. Allstate, discussed supra II.B.

46. 948 A.2d 955 (Conn. 2008).

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2009] CHOICE OF LAW IN THE AMERICAN COURTS IN 2008 281

passing through Connecticut en route from its point of departure in

New York to a destination inNew York. Both the deceased and the

driver worked for a New York

employer and the action was filed

against the driver. An

exception to the exclusivity provision of Con

necticut's workers' compensation statute allowed a tort action

against a co-employee for cases in which the injury was caused by a

co-employee's negligent operation of a motor vehicle. New York's

workers' compensation statute did not allow such an exeption. The

Supreme Court of Connecticut affirmed a summary judgment for the

defendant under New York law.

In previous cases, the court had articulated a three-prong test

that would allow the application of Connecticut workers' compensa

tion law ifConnecticut was: (a) the place of injury, (b) the place of the

employment contract, or (c) the place of employment relationship. Be

cause in this case the injury occurred in Connecticut, that state's

workers' compensation statute would be applicable and would permit

the tort action against the co-employee. However, the court concluded

that this test should apply "onlywhen the case involves a claim for

workers' compensation benefits and not when, as in the present case,

the case involves a tort claim."47

The court justified this distinction by contrasting the two catego

ries of cases. In workers' compensation cases, the court reasoned, the

issue is whether Connecticut has a "sufficient interest" in awarding

workers' compensation benefits under its law. Consequently, the

choice-of-law question in these cases is "not whether Connecticut has

the most significant relationship to or interest in the matter but,

rather, whether Connecticut's relationship or interest is sufficiently

significant to warrant an award of benefits under its workers' com

pensation statutes."48 In contrast, a "markedly different" choice-of

law question is posed in cases involving tortactions fallingwithin the

exceptions to the exclusivity provisions of Connecticut's workers'

compensation statute. In these cases, the choice-of-law question is

"not which state . . . has a sufficient interest in having its statutes

invoked for the benefit of the employee . . . [but] rather . . .which

state's law, to the exclusion of the law of all other potentially inter

ested states, is the governing or controlling law."49 This question, the

court concluded, should be answered under the court's general ap

proach for tort conflicts, namely the Restatement (Second).

Applying the Restatement, the court concluded that New York

law should govern, barring the action. New York had multiple con

tacts, including its status as the home state of all parties and the

place of the employment relationship. Normally, the fact that the de

47. Id. at 970 (emphasis added).

48. Id. (emphasis in original).

49. Id. at 971 (emphasis in original).

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

282 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE LAW [Vol. 57

fendant was driving in excess of Connecticut's speed limit (by forty

miles per hour) at the time of the accident would implicate Connecti

cut's interests in conduct-regulation. However, the court reasoned,

this interest is "diminished when the offending conduct occurs during

a brief entry into the state and when any accident that occurs as a

result of the undue speed or recklessness does not involve a Connecti

cut resident."50 Moreover, "Connecticut's interest in deterring and

punishing reckless driving [was] largely satisfied by [the driver's]

conviction of negligent homicide in this state."51

Thecourt concluded that Connecticut had "little or no interest in

vindicating its policy of permitting actions in accordance with the mo

tor vehicle exception" because Connecticut had "no ties to any person

or party involved in the accident." In contrast, said the court, because

New York was the place of the employment relationship and the vic

tim's home state, New York had "an obvious interest in compensating

the decedent's surviving dependents under its workers' compensation

scheme,"52 even if, one might add, that scheme deprived the depen

dents of the much more efficacious tort action.53

Three other appellate cases decided in 2008 involved similar is

sues. Two cases applied the law of the state of the accident, which

favored the defendant, rather than the law of the employment

state.54 The third case applied the law of the employment state,

which also favored the defendant, rather than the law of the state of

the accident.55 In a fourth case, the issue was whether an employer

who settled in good faithwith his injured employeewas immune from

50.Id. at 975.

51.Id.

52.Id.

53.For another Connecticut case involving similar facts and reaching the same

outcome, see Estate of Hodgate v. Ferraro, No. HHDX04CV054034694S, 2008 WL

4017532 (Conn. Super. Ct. Aug. 5, 2008) (holding that a Massachusetts employee of a

Massachusetts employer who was killed in a Connecticut traffic accident while riding

as a passenger in a car driven by a co-employee was not entitled to a tort action

against his employer under the exception to the exclusivity provisions of Connecti

cut's workers' compensation statute because the case was governed by the

Massachusetts workers' compensation statute).

54. See Estate of Torres v. Morales, 756 N.W.2d 662 (Wis. Ct. App. 2008) (apply

ing Wisconsin workers' compensation statute to bar a tort action against an employee

of a Texas employer filed by the estate of a Texas co-employee who was killed in a

traffic accident inWisconsin while riding as a passenger in a car driven by the defen

dant co-employee; the court did not discuss the Texas workers' compensation statute,

which arguably would have allowed the action); Anderson v. Commerce Const. Ser

vices, Inc., 531 F.3d 1190 (10th Cir. 2008) (decided under Kansas' lex loci delicti rule

and alternatively under the Restatement (Second); applying Kansas' workers' com

pensation statute and barring a tort action against a Nebraska contractor

general

filed by a Nebraska subcontractor's employee who was injured at an employment acci

dent in Kansas; the Nebraska statute would have allowed the action).

55. See Lane v. Celadon Trucking, Inc., 543 F.3d 1005 (8th Cir. 2008) (decided

under Arkansas' conflicts law; applying Indiana workers' compensation statute,

which allowed an Indiana employer to recoup workers' benefits to

compensation paid

its Indiana employee who was injured by a thirdparty in an Arkansas accident and to

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2009] choice of law in the american courts in 2008 283

a third-partyclaim for contribution brought by parties who contrib

uted to the employee's injury.The court applied the law of the state of

the injury,which allowed the contribution claim, rather than the law

of the state of the employment relationship, which barred the

claim.56

B. Common-Domicile Cases

Camp Jaycee57 and Jaiguay58 bring to sixty-one the number of

loss-distribution conflicts59 involving the common-domicile pattern

and decided by supreme courts in states that have abandoned the lex

loci delicti rule. Fifty-one of those cases (or eighty-four percent) have

applied the law of the common domicile, regardless of the particular

choice of law methodology the court followed.

Chart 1. Cases Applying Common-Domicile Law

^^^^^^^^^^^

#

exercise a lien against the proceeds of a tort settlement between the employee and the

third party; Arkansas' made-whole doctrine did not allow recoupment).

56. See Palmer v. Freightliner, LLC, 889 N.E.2d 1204 (111.App. Ct. 1st Dist.

2008). For a similar case, see Crete Carrier Corp. v. Barrow, No. 2007-CA-000568

MR, 2008 WL 901912 (Ky. Ct. App. Apr. 4, 2008) (applying law of employment state

rather than accident state and allowing employer's claim of subrogation in settlement

proceeds paid to injured employee by third party tortfeasor). For a non-employment

case involving an insurer's claim of subrogation formedical expenses paid to its in

sured, see Safeco Ins. Co. v. Jelen, 886 N.E.2d 555 (111.

App. Ct. 3d Dist. 2008).

57. Discussed supra at II .A.

58. Discussed supra at III.A.

59. In conduct-regulating conflicts, courts invariably apply the law of the state of

conduct and injury. See Symeon C. Symeonides, The American Choice-of-Law

Revolution: Past, Present and Future 213-20 (2006). Of course, as Camp Jaycee

illustrates, sometimes the issue turns on whether that law is, in fact, conduct

regulating.

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

284 the american journal of comparative law [vol. 57

Chart 2a. Babcock-Pattern Cases Applying

Common-Domicile Law

Thirty-five of the sixty-one cases involved the Babcock v. Jackson pat

tern (i.e., cases in which the law of the common domicile favors

recoverymore than the law of the state of conduct and injury). In

interest analysis terms, these cases present the classic false conflict

paradigm, where only the state of the common domicile has an inter

est in applying its law. Thirty-three of the thirty-fivecases applied

the law of the common domicile.60 One of the two cases that did not

do so was subsequently overruled,61 and the other case was factually

atypical.62

Twenty-six of the sixty-one cases (decided in eighteen states) in

volved the Camp Jaycee or converse-Bafecocfc pattern (i.e., cases in

which the law of the common-domicile prohibits or limits recovery

more than the law of the state of conduct and injury). These cases are

depicted in the table below.

60. For citations and discussion, see Symeonides, supra note 59, at 146-50; Eu

gene Scoles, Peter Hay, Patrick Borchers & Symeon C. Symeonides, Conflict of

Laws 799-806 (4th ed. 2004).

61. See Dym v. Gordon, 209 N.E.2d 792 (N.Y. 1965).

62. See Peters v. Peters, 634 P. 2d 586 (Haw. 1981). Peters arose out of a Hawaii

trafficaccident inwhich a New York domiciliary was injuredwhile riding in a rented

car driven by her husband. Her suit against her husband, and ultimately his insurer,

was barred by Hawaii's interspousal immunity law, but not by New York's law. The

court applied Hawaii law because the insurance policy that had been issued on the

rental car inHawaii had been written in contemplation ofHawaii immunity law.

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2009] choice of law in the american courts in 2008 2 85

Table 2. Law Applied in Converse-Babcock Pattern Cases

_Contact states and their laws_Law applied

Plaintiffs State of State of D's

|

Forum Domicile injury Conduct Dom. Pro-D Pro-P

# 1

Year Case

1 name \ state 1 1 Pro-D [ Pro-P [ Pro-P [ Pro-D \ \_

1 I 1966\McSwainPA I I PA 1 COL j COL j PA I 1 1

j'

2 1966Johnson NH IMMBPI NH NH

1_

3 1968 Conklin W$ ILL

WS W$ ILL

1

4 1968 Arnett ,KY OH KY KY

OH_1_

5 1968 Fuerste IA WSIA WS IA 1

6 1970 Ingersoll ILL WS

ILL WS ILL

1_

7 1971 MA

NH NH

Taylor_NH MA_1

8 1972 Issendorf NP ND , MN MN \ND 1

_

9 1972 Gagne :< MA -

';NH \NH\ y -NH ; MA _ 1

10 1973 Milkovich *'*j?y ON '"'vm\ \ ON_[_

11 1973 WS WS

Hunker_WS |gJB|j||g 1_

12 1978 Gordon NH MA/ME NH NH MA/ME 1

13 1985Johnson_ID ^^^^E IP ID SlBPiI 1

14 1985Schultz NY NY NY 118^1 1

^^^SP

15 1986Veazey NJ IHBB1 NJNJ 1

1118111118811

16 1987Hubbard ^^HK ILL IN ^SsKSi 1

17 1992Chambers lli|jgg| ^^BKIl MO MO1

18 1992Hataway MWBB AR AR 11MB 1

19 1994

Dillon ID ^HHIK ID ID 11111111

20 1995 CAN ME CAN 1

Collins_ME_ ^me

21 1998

Myers VT ^BBBfil VT VT 8MB 1

22 1999Lessard NH ^HH^ NH NH 11H^ 1

23 2000Martineau ||||lig|| Quebec SHPlMWi 1

Quebec

24 2007 NEB COL COL NEB 1

Heinze_NEB

25 2008 Camp Jaycee NJ NJ PA NJ

1 PA

26 2008 Jaiguay CN ^SWS^ CN 1 CN

26 15 18 8 18 8 18 8

Totals_

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

286 the american journal of comparative law [vol. 57

Chart 2b. Converse-JBabcock Pattern Cases Applying

Common-Domicile Law

As the table indicates, eighteen of the twenty-six cases (or sixty

nine percent) applied the pro-defendant law of the parties' common

domicile.63 In eight of the eighteen cases, that lawwas also the law of

63. In chronological order, these cases are: McSwain v. McSwain, 215 A.2d 677

(Pa. 1966) (Colorado trafficaccident involving Pennsylvania domiciliaries; applying

Pennsylvania intrafamily immunity rule barring wife from suing her husband for

death of infant daughter killed in Colorado accident); Johnson v. Johnson, 216 A.2d

781 (N.H. 1966) (New Hampshire accident involvingMassachusetts spouses; applying

Massachusetts interspousal immunity rule barring wife's action); Fuerste v. Bemis,

156 N.W.2d 831 (Iowa 1968) (Wisconsin accident involving Iowa parties; applying

Iowa guest statute barring suit); Ingersoll v. Klein, 262 N.E.2d 593 (111.1970) (Iowa

accident involving Illinois parties; applying Illinois damages law, which was less

favorable to plaintiff than Iowa law); Issendorf v. Olson, 194 N.W.2d 750 (N.D. 1972)

(Minnesota accident, North Dakota parties; applying North-Dakota's pro-defendant

contributorynegligence rule); Hunker v. Royal Indem. Co., 204 N.W.2d 897 (Wis.

1973) (applying Ohio law barring suits against co-employees, rather thanWisconsin

law that permitted co-employee suits, in action between Ohio residents arising from

automobile collision inWisconsin); Johnson v. Pischke, 700 P.2d 19 (Idaho 1985)

(Idaho accident, Saskatchewan parties; applying Saskatchewan's workers' compensa

tion immunity rule); Schultz v. Boy Scouts of America, Inc., 480 N.E.2d 679 (N.Y.

1985) (applying the charitable immunity rule of New Jersey, the state where the

plaintiffsand one of the defendants were domiciled, rather than the law ofNew York,

the state where thewrongful conduct occurred and which did not provide for charita

ble immunity);Veazey v. Doremus, 510 A.2d 1187 (N.J. 1986) (New Jersey accident

involvingFlorida spouses; applying Florida's interspousal immunity rule, barring the

action); Hubbard Mfg. Co. v. Greeson, 515 N.E.2d 1071 (Ind. 1987) (Illinois injury,

Indiana parties; applying Indiana's pro-manufacturer products liability law); Cham

bers v. Dakotah Charter, Inc., 488 N.W.2d 63 (S.D. 1992) (Missouri accident involving

South Dakota parties; applying South Dakota's pro-defendant contributory negli

gence rule); Hataway v. McKinley, 830 S.W.2d 53 (Term. 1992) (Arkansas accident

involving Tennessee parties; applying Tennessee's pro-defendant contributorynegli

gence rule); Dillon v. Dillon, 886 P.2d 777 (Idaho 1994) (applying Saskatchewan's one

year statute of limitations rather than Idaho's two-year statute of limitations in a

wrongful death action filedby formerwife of Saskatchewan husband for causing the

death of their daughter in a trafficaccident in Idaho); Collins v. Trius, Inc., 663 A.2d

570 (Me. 1995) (applying Canadian law, which did not allow recovery for pain and

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2009] CHOICE OF LAW IN THE AMERICAN COURTS IN 2008 2 87

the forum state,64 which means that, in those cases, the plaintiffs

chose to sue in their home state even though that state had a pro

defendant law, rather than take advantage of the pro-plaintiff law in

the accident state. In ten of the eighteen cases, the plaintiffs chose to

sue in the state of the accident, which had a pro-plaintiff law, but

were unable to persuade the court to apply its law.65

Eight of the twenty-six cases applied the pro-plaintifflaw of the

state of conduct and injury. Seven of the eight cases (except for Camp

Jaycee) were filed in the accident state, which had a pro-plaintiff law,

and all seven cases applied the law of the forum. Five of those cases

were decided in states that, at least then, followed Leflar's better law

approach ?Wisconsin,66 Minnesota,67 and New Hampshire68?while

the sixth case was decided under Kentucky's unapologetically paro

chial lex fori approach.69 The seventh case was factually atypical,70

and the eighth case was Camp Jaycee,71 in which the plaintiff was

able to persuade the court to apply the pro-plaintiff law of the non

forum state. As Camp Jaycee indicates (assuming a sympathetic

suffering, to a case arising out of a Maine accident involving Canadian parties); Myers

v. Langlois, 721 A.2d 129 (Vt. 1998) (applyingQuebec law and denying a tortaction in

a dispute between Quebec parties arising out of a Vermont accident); Lessard v.

Clark, 736 A.2d 1226 (N.H. 1999) (applying the law ofOntario, the parties' common

domicile, which provided for lower recovery, rather than the law of New Hampshire,

the accident state); Martineau v. Guertin, 751 A. 2d 776 (Vt. 2000) (described in infra

note 70); Heinze v. Heinze, 742 N.W.2d 465 (Neb. 2007) (Colorado accident involving

Nebraska parties; applying Nebraska's guest statute, barring the action).

64. See cases ## 1, 5-6, 8, 16-18, and 24 in above table.

65. See cases ## 2, 11, 13-15, 19-22, and 26 in above table.

66. See Conklin v. Horner, 157 N.W.2d 579 (Wis. 1968) (applyingWisconsin law

to allow an action by Illinois guest-passenger against an Illinois host-driver and aris

ing out of a Wisconsin accident; Illinois' guest statute barred the action). But see the

more recent case Hunker v. Royal Indem. Co., described in supra note 63.

67. See Milkovich v. Saari, 203 N.W.2d 408 (Minn. 1973) (applyingMinnesota law

to allow an action by Ontario guest-passenger against Ontario host-driver arising out

of a Minnesota accident; Ontario's guest statute barred the action).

68. See Taylor v. Bullock, 279 A.2d 585 (N.H. 1971) (New Hampshire accident

involving Massachusetts spouses; applying New Hampshire rule allowing inter

spousal suits rather than Massachusetts rule prohibiting such suits); Gagne v. Berry,

290 A.2d 624 (N.H. 1972) (New Hampshire accident involvingMassachusetts domicil

iaries; applying New Hampshire law, which allowed the action, rather than

Massachusetts' guest statute, which allowed recovery only for injuries caused by gross

negligence); Gordon v. Gordon, 387 A.2d 339 (N.H. 1978) (New Hampshire accident

involving Massachusetts spouses who later moved to Maine; applying New Hamp

shire's law and an action, which was

allowing barred by Maine's interspousal

immunity rule and Massachusetts statute of limitation). But see the more recent case

Lessard v. Clark, described in supra note 63.

69. See Arnett v. Thompson, 433 S.W.2d 109 (Ky. 1968) (applyingKentucky law

and allowing an action between Ohio spouses thatwas barred by Ohio's interspousal

immunity rule and guest statute).

70. This case is Martineau v. Guertin, 751 A.2d 776 (Vt. 2000) (discussed in

Symeonides, 2000 Survey 16). InMartineau, the parties were domiciled in the same

state, but they resided together in another state, and the accident occurred in a third

state (the forum), the law ofwhich was identical to the residence state. This factor

tipped the scales in favor of the accident state.

71. Camp Jaycee is discussed supra at II.A.

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

288 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE LAW [Vol. 57

court), a plaintiff ismore likely to succeed if she can credibly argue

that the rule of the state of conduct and injury has a strong conduct

regulating component (in addition to its loss-distributing function).

C. Cross-Border Torts

v. Sea Transfer

In Dolan Corp.,72 which was decided by New

Jersey's intermediate court under interest analysis before Camp

Jaycee, the court applied New York's pro-plaintiff law to a case aris

ing from a New Jersey trafficaccident that injured a New Jersey

plaintiff. Interestingly, however, Dolan was one of relatively few traf

fic accident cases inwhich the conduct primarily responsible for the

injury takes place in one state (in this case, New York) and the injury

occurs in another state (New Jersey in this case).

A New York driver acting for his New York employer drove a

tractor-trailer briefly through New Jersey en route from one point in

New York to his destination at another point in New York. The trac

tor-trailer was composed of a cab belonging to the driver's employer

(a motor carrier based in New York) and a chassis and a large cargo

container belonging to the defendant (an ocean carrier with its princi

pal place ofbusiness inNew Jersey). The container fell offthe chassis

while the truckwas being driven throughNew Jersey and injured the

plaintiff, a New Jersey domiciliary, who was driving his car on the

opposite side of a divided highway. The court found that the cause of

the accident was not the truck driver's negligence in New Jersey, but

rather his negligence at the terminal inNew York when he loaded the

container and failed to properly insert two pins that would lock the

container onto the chassis. Once the driver left the terminal with the

improperly-secured container, the court said, "his tractor-trailer was

an accident waiting to happen."73

Under a New York statute, which specifically addressed compos

ite vehicles like the tractor-trailer involved in this case, the owner of

the container would be liable for the negligence of the driver. Under

New Jersey law, the owner would not be liable in the absence of fault.

The court applied the New York statute, stressing the statute's con

duct-regulating purpose and noting that, although the statute was

not, strictly speaking, a "rule of the road," its main purpose was to

indirectly promote traffic safety by "discouraging] owners from lend

ing their vehicles to incompetent or irresponsible drivers."74 The

court said that this was particularly relevant in this case because

both the "lending" ofwhat became part of the vehicle (the chassis and

72. 942 A.2d 29 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. 2008), cert, denied, 950 A.2d 907 (N.J.

May 16, 2008).

73. Dolan, 942 A.2d at 38.

74. Id. at 34 (internal quotation marks omitted).

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2009] CHOICE OF LAW IN THE AMERICAN COURTS IN 2008 2 89

container) and "the primary act of negligence"75 occurred in New

York. Thus, "[a] 11of the activitywithin New York strongly implicated

New York's legislative policy to encourage vehicle owners to do more

to ensure safety on the road."76 The fact that the injury occurred in

New Jersey (rather than New York) was "fortuitous," said the court,

when the driver "detoured through New Jersey to avoid New York

City traffic."77

The court also acknowledged that theNew York statute also had

a loss-distributing purpose by allowing injured persons to recover

from financially responsible insured persons. The court noted that

this purpose ismore relevant when the victim is a New York domicili

ary, but reasoned that in this case the New Jersey victim, who was

employed inNew York and commuted toNew York on a daily basis,

was "well within the universe of persons whose safety the New York

law was aimed at protecting" and that "his devastating injuries de

prived [his New York employer] of a long-term employee."78

As for New Jersey's interests, the court found that New Jersey's

policy of "equating liabilitywith fault" did "not outweigh New York's

policy to encourage traffic safety and ensure an adequate recovery for

accident victims."79 Even the fact that the defendant had its principal

offices in New Jersey did not trigger New Jersey's defendant-protect

ing interest because the defendant, having acted in New York on a

"

daily basis and at all critical times, had not justifiably relied on the

shelter afforded 80

by New Jersey law."

The result in Dolan is consistent with the results reached in the

vast majority of conflicts cases involving cross-border torts (other

than products liability81)and decided by state and federal courts in

states that have

abandoned the lex loci delicti rule. In a recent com

prehensive study,82 this author has examined all such cases?a total

of 105?decided over the last four decades. Depending on the content

of the laws of the state of conduct and the state of injury, these cases

fall into two main patterns:

(1) cases in which the state of conduct has a pro-defendant law,

while the state of injuryhas a pro-plaintifflaw (Pattern 1); and

(2) cases like Dolan in which the state of conduct has a pro

plaintiff law, while the state of injury has a pro-defendant law

(Pattern 2).

75. Id. at 38.

76. Id.

77. Id.

78. Id.

79. Id.

80. Zd. (internal quotation marks omitted).

81.For product liability conflicts, see Symeonides, supra note 59, at 265-364.

82.See Symeon C. Symeonides, Choice of Law in Cross-Border Torts (forthcom

ing) available at SSRN:http://ssrn.com/abstract=1328191.

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

290 the american journal of comparative law [Vol. 57

These patterns can be further subdivided, depending on the par

ties' domiciles and whether the conflict involves conduct-regulation

or loss-distribution issues, but these subdivisions rarely affect the re

sult (although they do affect the analysis). The following table

summarizes the results of the 105 cases.

Table 3. Law Applied in Cross-Border Conflicts

Pattern 1

Pro-P Pro-D Forum

Injury Conduct law law law Non-Forum

Conduct-Regulation (30) 27_4_ 27_4

25_6

Loss-Distribution

(17)_16_1_ 16_1

12_5

Total(47)_ 43 1 5 | | 43 [ 5 | | 37 | 11

_ Pattern 2 __

Conduct-Regulation 34

(41)_7 34_7

24_17

Loss-Distribution 13

Total 1 10 1 47 j | 47 | 10 | | 31 | 26

(16)_3 13_3

7_9

(57)

Grand-Total

(102) I 53 I 52 I I 90 1 15 1 1 68 1 37

"Percentages 1 50% | 50% | | 86% | 14% | | 65% | 35%

As the table indicates, courts that have joined the revolution

have reached fairly uniform results in resolving cross-border tort con

flicts (despite using different approaches and invoking varied

rationales). Specifically:

(1) the cases are almost evenly split (53 to 52) between applying

the law of the place of conduct and the law of the place of injury;

(2) the vast majority of the cases (90 out of 105 cases, or 86%)

have applied whichever of the two laws favored theplaintiff; and

(3) almost two-thirds of the cases (68 out of 105 cases, or 65%)

have applied the law of the forum state.

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2009] choice of law in the american courts in 2008 291

Chart 3. Conduct or Injury? Chart 4. Pro-P and Pro-D Law

Chart 5. Forum and Non-Forum Law

D. Other Torts

Cases involving state tort immunity,83 professional malprac

tice,84 and deceptive trade practices86 are among the other cases

decided by appellate courts in 2008 and worth noting.

83. See Athay v. Stacey, 196 P.3d 325 (Idaho 2008), reh'g denied, (Oct. 15, 2008).

84. See Thabault v. Chait, 541 F.3d 512 (3d Cir. 2008) (decided under New Jersey

conflicts law; auditor malpractice).

85. See GJP, Inc. v. Ghosh, 251 S.W.3d 854 (Tex. App. Austin 2008), reh'g denied

(Apr. 17, 2008).

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

292 the american journal of comparative law [Vol. 57

IV. Products Liability

A. Foreign Plaintiffs and Forum Non Conveniens

With the 2008 decision inKedy v.A.W. Chesterton Co.,86 Rhode

Island became

the forty-seventh state of the United States to for

mally adopt the doctrine of forum non conveniens (FNC). Twenty-two

states now have statutes or civil procedure rules codifying the doc

trine, while twenty-five states have supreme court precedents to the

same effect.87InKedy, the Rhode Island Supreme adopted the FNC

doctrine (or declared that it has always been part of Rhode Island

law) and, rather than remanding the case, applied the doctrine to the

case at hand. It did not matter that the trial court, having dismissed

the FNC motion as unavailable under Rhode Island law, had not de

veloped a record regarding the private and public interest factors

upon which the FNC doctrine depends.

Kedy involved twenty-nineproduct liability actions filed by Ca

nadian residents

against several American asbestos manufacturers,

alleging injuries caused by workplace exposure in Canada to products

containing asbestos. In dismissing the action on FNC grounds, the

court noted, inter alia, that "no one other than the attorneys involved

actually is located in Rhode Island," that "literally all the witnesses

and parties would have to travel to Rhode Island for the trial," and

that "the likelihood that Canadian or other foreign law would apply

in these cases would place additional, although not insurmountable,

burdens" upon Rhode Island courts.88

In Varo v. Owens-Illinois, Inc. ,89 another product liability action

for asbestos exposure filed by fifteen Spanish domiciliaries against

American asbestos manufacturers in New Jersey, the plaintiffs suc

ceeded in defeating a FNC motion. In this case, the asbestos was

manufactured and sold in New Jersey, and plaintiffs' exposure to as

bestos occurred aboard U.S. warships?which are by legal fiction part

of U.S. territory, even when, as in this case, they were docked at a

naval base in Spain. The court observed that, while there was little

reason to assume that New Jersey was a convenient forum for the

plaintiffs, there was "more reason to doubt the convenience to defen

dant of defendant's preferred forum more than 3000 miles away from

its own home."90

86. 946 A.2d 1171 (R.I. 2008).

87. According to theKedy court, the three states that have not adopted the doc

trine (or have not spoken on it) are Montana, Idaho, and Oregon. See Kedy, 946 A.2d

at 1180 n.9. For a 2008 Montana case, see Cook v. Soo Line R. Co., 198 P.3d 310

(Mont. 2008) (discussed infra at VIII). For a recent U.S. Supreme Court decision on

FNC, see infra IX.D.

88. Id. at 1188.

89. 948 A.2d 673 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. 2008).

90. Id. at 683.

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2009] CHOICE OF LAW IN THE AMERICAN COURTS IN 2008 2 93

The court noted that "the potential application of Spanish law

d[id] not weigh in favor of dismissing plaintiffs' complaints in New

Jersey,"91 and that "defendant's tortious conduct in New Jersey?the

manufacture, and sale of asbestos-containing . . .

marketing products

provide [d] a sufficient factual nexus with the State to warrant reten

tion of jurisdiction." The court concluded that New Jersey had "an

undeniable, strong interest in assuring the safety of products manu

factured, distributed, marketed and sold [in New Jersey], and

correspondingly in providing a forum for redress of allegedly wrong

ful conduct of its corporate residents."92

In In re Pirelli Tire, L.L.C.,93 a products liability action brought

by Mexican domiciliaries against a U.S. car tire manufacturer, the

Texas Supreme Court reversed a lower court's dismissal of defen

dant's FNC motion. The tire was manufactured at an Iowa plant

owned by defendant, a Georgia-based corporation, and was installed

on a used pickup truck that was sold to a Mexican domiciliary in

Texas and then taken to Mexico. The tire exploded while the truck

was being driven on a Mexican road, causing the truck to roll, killing

the plaintiffs decedent, a Mexican domiciliary.

The court found that "[t]he happenstance that the truck was in

Texas for eleven days before it was sold and imported to Mexico is

simply insufficient to provide Texas with any interest in this case."94

In contrast, the court thought that "Mexico's interest in protecting its

citizens and seeing that they are compensated for their injuries [was]

paramount"95 even ifMexican law, by limiting the amount of com

pensatory damages, protected defendants more than plaintiffs. "The

safety of Mexican highways and products within the country's bor

ders are also Mexican interests,"96 said the court, even though, by

refusing to adopt strict liability and requiring proof of negligence,

Mexican law made it difficult for plaintiffs to succeed in suing prod

uct manufacturers. The court also commented that the Mexican

plaintiffs "cannot logically claim that it is more convenient for them

to litigate in Texas than in Mexico,"97 but the court did not comment

on whether it was more convenient for the U.S. defendant to litigate

in Mexico.

One preliminary question in Pirelli was whether Mexico pro

vided an alternative forum. The defendant had stipulated that it

would submit to personal jurisdiction inMexico and would not assert

any statute-of-limitations defense based on the time that had elapsed

91. Id. at 684.

92. Id. at 685.

93. 247 S.W.3d 670 (Tex. 2007), reh'g denied (Mar. 28, 2008).

94. Id. at 679.

95. Id.

96. Id.

97. Id.

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

294 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE LAW [Vol. 57

since the Texas lawsuit was filed. The plaintiffs argued that such an

anticipatory waiver of the statute of limitations was not enforceable

in Mexico and that a Mexican court might not assert jurisdiction

under such circumstances. The court dismissed the argument.

In In re General Electric Co. 98 a product liability action filed in

Texas by a Maine domiciliary who was exposed to asbestos inMaine,

the plaintiff argued that Maine was not an alternative forum in

which his claims could actually be "tried."99 If he sued in Maine, he

argued, his case would be removed to federal court (because none of

the defendants had their principal place of business inMaine) and

would be transferred from there to the federal Multi-District Litiga

tion (MDL) Court No. 875. At the time, therewere 32,892 asbestos

cases pending before the MDL court, andthese cases usually lan

guish for years and "virtually nothing happens to them at all."100 The

plaintiff stated that he was seriously illwith asbestosis and that ifhe

had to litigate inMaine, he would not survive long enough to have his

case tried. Indeed, the plaintiff died before the case was heard by the

Texas Supreme Court, but this did not prevent the court from dis

missing his arguments as "speculative."101

In Hernandez v. Ford Motor Co.,102 a products liability action

similar toPirelli but brought inMichigan, theMexican plaintiffsalso

argued that Mexico did not provide an alternative forum because

Mexican courts would not assume jurisdiction. The plaintiffs noted

that, in two cases involving the same defendant that were dismissed

on FNC grounds in theUnited States and then re-filed inMexico, the

Mexican courts held that they did not have jurisdiction despite know

ing that, as in Pirelli and Hernandez, the defendant was willing to

consent to the Mexican courts'jurisdiction. After noting that "a suspi

cious haze"103 surrounded the plaintiffs in those cases, the Michigan

court dismissed the argument. The court pointed out that the plain

tiffs' attorneys (who also appeared as plaintiffs' Mexican law experts

98. 271 S.W.3d 681 (Tex. 2008).

99. Id. at 687.

100. Id. at 684.

101. Id. at 688. In Satterfield v. Crown Cork & Seal Co., Inc., 268 S.W.3d 190 (Tex.

App. Austin 2008), reh'g overruled (Oct. 07, 2008), another asbestos case filed by a

who also died of asbestosis before his case was heard, the issue was the con

plaintiff

stitutionality of a Texas statute that limited liability for asbestos claims against

successor to the value of the predecessor corporation at the time of the

corporations

merger. The statute mandated its application to: (a) multistate cases "to the fullest

extent permissible under theUnited States Constitution," id. at 199, even if the case

would otherwise be governed by foreign law; and (b) even topending cases. In a 2:1

decision, the court found that, without a grace period, the statute violated the Texas

Constitution's against retroactive laws. The dissent argued that the stat

prohibition

ute was not unconstitutional because itmerely altered Texas' choice-of-law rules, and

that the plaintiff did not have a vested right in a remedy provided by those rules.

102._N.W.2d_, 2008 WL 4057538 (Mich. Ct. App. Sept. 2, 2008), appeal de

nied, 759 N.W.2d 396 (Mich. 2009).

103. Id. at *4.

This content downloaded from 41.66.201.225 on Wed, 9 Oct 2013 14:07:18 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2009] CHOICE OF LAW IN THE AMERICAN COURTS IN 2008 2 95