Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Intentionalpersonalitychangecoaching AramdomisedcontrolledtrialofparticipantselectedpersonalityfacetchangeusingtheFive-FactorModelofPersonality

Uploaded by

generico2551Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Intentionalpersonalitychangecoaching AramdomisedcontrolledtrialofparticipantselectedpersonalityfacetchangeusingtheFive-FactorModelofPersonality

Uploaded by

generico2551Copyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/326848426

Intentional personality change coaching. A randomised controlled trial of

participant selected personality facet change using the Five-Factor Model of

Personality

Article in International Coaching Psychology Review · September 2014

DOI: 10.53841/bpsicpr.2014.9.2.196

CITATIONS READS

37 1,998

3 authors:

Sue Martin Lindsay G. Oades

7 PUBLICATIONS 126 CITATIONS

University of Melbourne

171 PUBLICATIONS 6,483 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

SEE PROFILE

Peter Caputi

University of Wollongong

4 PUBLICATIONS 85 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Sue Martin on 07 August 2018.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Paper

Intentional personality change coaching:

A randomised controlled trial of

participant selected personality facet

change using the Five-Factor Model of

Personality

Lesley S. Martin, Lindsay G. Oades & Peter Caputi

Objectives: Recent literature suggests that personality may be more amenable to change than was previously

thought, and that participant selected intentional personality change may be beneficial. The aim of this

study was to examine the effects of a 10-week structured intentional personality change coaching programme

on participant selected personality facets.

Design: Participants were assigned to the personality coaching group or a waitlist control group using a

waitlist control, matched, randomised procedure (personality coaching group, N=27; waitlist control group,

N=27).

Method: A structured coaching programme, designed to identify and modify a limited number of personality

facets, chosen by the client, was employed.

Results: Participation in the personality change coaching programme was associated with significant positive

change in participant selected facets, with gains maintained three months later. Neither age of participant

nor number of facets targeted significantly affected change outcomes.

Conclusions: These findings suggest that a structured personality change coaching programme may facilitate

beneficial personality change in motivated individuals.

Keywords: Intentional personality change coaching.

T

He assertion that individuals may while emotionality was predominantly associ-

beneficially change their personality ated with negative outcomes. these findings

through coaching is both challenging suggests that increasing or decreasing

and recent. Martin, oades and Caputi domains in the direction associated with

(2012) proposed that exploration of this positive outcomes may be beneficial.

potential was warranted, based on an exten- some authors have proposed that as the

sive body of literature suggesting that literature has now demonstrated that

personality domains (traits) had wide personality domains are predictive of many

ranging consequences. for example, a meta- life outcomes, it would be useful if future

analysis by ozer and Benet-Martinez (2006) research explored how to change personality

found predictive relationships between Big 5 in ways that are beneficial to the individual.

(five-factor) personality domains and for example, a four-year study of 8625

numerous important life outcomes, at the australians (Boyce, Wood & powdthavee,

individual, relationship and organisational/ 2012) found that personality can change

community levels. four of the five Big 5 over this period of time, and that these

domains were predominantly associated with changes are both important and meaningful,

positive outcomes (i.e. conscientiousness, as personality is the strongest and most

extraversion, agreeableness and openness), consistent predictor of life-satisfaction.

196 International Coaching Psychology Review l Vol. 9 No. 2 September 2014

© The British Psychological Society – ISSN: 1750-2764

Intentional personality change coaching

Title

He further proposed that there would be tions (e.g. McCrae & Costa, 1994, 2003),

substantial advantages in gaining a better findings from more recent literature cast

empirical understanding of how personality doubt on this assumption.

domains might be beneficially modified. a number of intervention studies have

Cuijpers et al. (2010) suggested that the suggested that personality is amenable to

economic costs of high levels of domain change. tang et al. (2009) found that

emotionality were substantial in terms of greater personality changes occurred in

both health care costs and unemployment. depressed participants in two treatment

they found that individuals who had higher groups (i.e. anti-depressant medication and

levels of trait emotionality were more vulner- cognitive therapy over 16 weeks), compared

able to a wide range of mental health disor- to a placebo control group, even after

ders (e.g. depression, anxiety disorders, recovery from depression was controlled for.

schizophrenia, eating disorders and person- this study measured personality using the

ality disorders) and physical disorders (e.g. neo five-factor inventory (Costa &

medically unfounded physical complaints, McCrae, 1992). participants taking anti-

cardiovascular disease, asthma, and irritable depressant medication reported over three

bowel syndrome). their research suggested times as much change on domain extraver-

that in addition to the human costs, high sion and over six times as much change on

emotionality impacted heavily on the health domain emotionality than the control

system. their analysis suggested that the group, even when matched for improvement

incremental costs (per one million people) in depression. significantly greater change

of the highest 25 per cent of scorers on on domain extraversion was also recorded in

emotionality resulted in us$1.393 billion in the cognitive therapy group than the

health care costs. placebo group, after being matched for

these findings led Cuijpers et al. (2010) improvement in depression. these findings

to propose that ‘we should start thinking suggest that interventions used to treat

about interventions that focus not on each of depression can have an effect on personality

the specific negative outcomes of neuroti- (domain level change) separate from its

cism [emotionality], but rather on the effect on depression (state level change),

starting point itself’ (p.1086). similarly, in a and that interventions can achieve signifi-

review of the mechanisms by which person- cant changes in personality domains in as

ality domains predict consequential little as 16 weeks.

outcomes, Hampson (2012) proposed that similarly, De fruyt et al. (2006) found

‘as evidence has mounted for the important that treatment with medication and therapy

role played by personality domains in conse- was associated with a substantial reduction in

quential life outcomes, there is increasing neuroticism, and minor gains on extraver-

interest in the possibility of using this knowl- sion, openness, agreeableness, and conscien-

edge to bring about beneficial personality tiousness. furthermore, a six-week broad

change’ (p.333). the findings from these based multimodal outpatient programme

studies suggest that empirical exploration of for substance abusers achieved significant

personality change interventions is both shifts on all five personality domains , with

warranted and timely. changes on three domains being maintained

it is, therefore, useful to explore the liter- 15 months later (i.e. reduced emotionality

ature around whether personality change and increased agreeableness and conscien-

appears to be possible, and how that might tiousness)(piedmont, 2001).

be achieved. Martin et al. (2012) clarified a number of studies have explored if

that, whereas some literature had argued interventions can change the personality of

that personality was relatively resistant to individuals not suffering from psychological

change without long-term intensive interven- problems. for example, nelis et al. (2011)

International Coaching Psychology Review l Vol. 9 No. 2 September 2014 197

AuthorS.name

Lesley Martin, Lindsay G. Oades & Peter Caputi

found that 18 hours of emotional compe- selected personality change was not specifi-

tence training resulted in longer term cally targeted. this observation suggested

changes in three of the five Big 5 personality that stronger personality change results may

domains. six months after the emotional be achievable if: (1) participants consciously

competence interventions participants were choose to change aspects of their person-

less emotional and more extraverted and ality; (2) they had professional support to do

agreeable, with effect size suggesting that this; and (3) professionals had access to

such change was meaningful. evidence-based resources specifically

a meta-analysis of 16 transcendental designed to facilitate participant selected

meditation studies (orme-Johnson & personality change.

Barnes, 2013) found that individuals whose nevertheless, some may argue that what

scores on facet anxiety placed them between we are seeing in many of these cited studies

the 80th and the 100th percentile range is state rather than domain based change.

achieved significant reductions in facet this state based explanation is unlikely, as,

anxiety (down to between 53rd and 62nd firstly, personality inventory items typically

percentile range) from 20 minutes of tran- encapsulate more enduring views of self (e.g.

scendental meditation twice daily. further- ‘i often feel inferior to others’. secondly, the

more, meaningful benefits were achieved duration of the change noted in some of

within the initial few weeks, and effects were these studies was substantial, (e.g. nelis et al.

sustained at three year follow up. similarly, [2011] was six months, piedmont [2001] was

a 16-week inductive reasoning training 30 months and orme-Johnson and Barnes

programme for older adults increased the [2013] was three years). finally, tang et al.

domain openness to new experience over (2009) found significant domain level

the 30-week assessment period (Jackson et change from their interventions, even after

al., 2012). controlling for state level change. Hence, in

spence and Grant (2005) assessed the combination the above findings provide

impact of 10 life coaching sessions on support for the concept of personality being

Big 5 personality domains (using both peer amenable to change.

and professional coaching groups). person- Consistent with this view, Magidson et al.

ality change was not targeted by the (2012) proposed that personality domains,

coaching interventions in this study (i.e. it such as conscientiousness, may be amenable

was an incidental measure). nevertheless, to change through bottom up behavioural

significant change was achieved on two of interventions, and provided both theoretical

five domains (i.e. increased extraversion and discussion of this possibility, and a case study

openness to experience) in the peer illustrating this approach. Dweck (2008)

coaching group. this study provided some proposed that beliefs are a major determi-

evidence that aspects of personality may be nant of personality, that beliefs can be

amenable to change through coaching, even changed, and when beliefs change, so too

when not targeted. spence and Grant (2007) does personality.

note, not surprisingly, that constructs that Martin et al. (2012) proposed that client

are targeted by coaching interventions are selected personality change could be both

more likely to change than constructs that beneficial and achievable, using resources

are not, implying that if personality change is specifically designed for this purpose. they

being observed in the absence of targeted did, however, emphasise the importance of

efforts, then even greater change is likely to personality change goals being determined

occur if coaching specifically targets such by the client, and internally motivated.

change. Martin et al. (2012) further suggested that

in the above intervention studies that the five-factor Model of personality

evidenced personality change, participant provides a useful model for exploring

198 International Coaching Psychology Review l Vol. 9 No. 2 September 2014

Intentional personality change coaching

Title

personality change, and that working at the avoid participants who chose a high number

more detailed facet level would be more of facets having a disproportionate influence

beneficial than working at the broader on the results, an average of the targeted

domain level. they proposed that the facets was calculated for each participant at

neo pi-r (Costa & McCrae, 1992), or a each data collection time. reverse scoring

reputable proxy, could provide a suitable was used for facets that clients wished to

measure of personality. Whereas they decrease. this averaged score was then

acknowledged that personality change could termed average targeted facet score (atfs)1,

be explored within either a one to one and this became the personality construct

coaching or counselling/therapy context, explored. for example, if a client chose to

they recommended that ‘for clients without increase two facets (e.g. self-discipline and

major psychopathology, personality change assertiveness), and decrease one facet (e.g.

interventions may be more consistent with anxiety) then the scores for self-discipline

coaching, and a coaching approach may and assertiveness would be added to a

offer certain advantages’ (p.189). reversed score for anxiety, and the total

ten coaching sessions were proposed as would be divided by three. the result would

an appropriate duration over which to then be the atfs for that data collection

initially explore intentional personality point. therefore, it was hypothesised that,

change, based on positive outcomes firstly, the intervention group will have

achieved by a number of 10-session coaching significantly higher atfs when compared to

studies (Green, Grant & rynsaardt, 2007; the control group, and secondly, that there

spence & Grant, 2005, 2007). one-to-one would be significant increases in atfs over

coaching with an appropriately trained the coaching period.

professional was recommended, due to: (1)

the sensitive personal nature of personality Method

profile material; and (2) the importance of Participants

such professionals being well versed in total participants were 54 adults aged

psychometrics and personality, and compe- between 18 and 64 years (M=42.18,

tent working with emotional distress. SD=12.44). participants consisted of eight

furthermore, Martin et al. (2012) encour- males and 46 females without major

aged empirical research to further explore psychopathology (see procedures for exclu-

these notions. sions). three individuals were excluded

to this end, Martin, oades and Caputi prior to the study, due to axis ii disorders.

(2014) developed a step-wise process of the 54 participants were assigned to the

intentional personality change, drawing on personality coaching group or the waitlist

coach training material developed in an control group using a waitlist control,

earlier phase of their research. the current matched, randomised procedure (person-

study is designed to empirically explore ality coaching group, N=27; waitlist control

whether these resources, applied over 10 group, N=27). participants were firstly

sessions of coaching, can facilitate change on matched on sex (male/female) and then on

participant selected personality facets. it was age range (18 to 30, 31 to 50, 51+ years). the

considered important that the study first author randomly assigned individuals

reflected participant preferences of having within each group to either the coaching

the flexibility to choose which facets were group or the waitlist control group. the

targeted, and how many. therefore, participants that withdrew (six in the waitlist

different participants choose different types group and none in the coaching group)

and numbers of facets. as it was necessary to were replaced by individuals matched by age

1 atfs=average targeted facet score.

International Coaching Psychology Review l Vol. 9 No. 2 September 2014 199

AuthorS.name

Lesley Martin, Lindsay G. Oades & Peter Caputi

grouping and gender. all waitlist control Experimental design

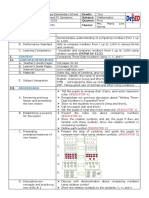

participants that completed the 10 sessions table 2 illustrates the study design, including

of coaching completed a personality inven- data collection timing for the neo pi-r and

tory three months later. one participant key research stages for the two groups.

from the personality coaching group did not (other inventories were completed to assist

furnish a three month follow up personality coaching processes, but changes in these

inventory, but their data was included in were not measured over time).

analysis up to end of coaching. the compo-

sition of the 54 participants by age and

gender is summarised in table 1.

Table 1: Age and gender of participants.

Age Female – Female – Male – Male – Total

Coaching Waitlist Coaching Waitlist

Group Group Group Group

18–29 4 4 1 1 10

30–49 10 11 2 2 25

50+ 8 8 1 2 19

Total 22 23 4 5 54

Table 2: Experimental design of study and NEO PI-R data collection timing.

PCG

A B C F

data

PCG

10 week coaching period 12 week follow-up period

stages

WCG

A C D E F

data

WCG

Waitlist period 10 week coaching period 12 week follow-up period

stages

Week 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32

Note: PCG=personality coaching group. WCG=waitlist control group. A–F indicate data collecting points.

200 International Coaching Psychology Review l Vol. 9 No. 2 September 2014

Intentional personality change coaching

Title

Measures or the waitlist control group (and completed

the 240 item neo pi-r (Costa & McCrae, a 10-week waiting period, followed by a

1992), a well-established personality assess- 10-week personality coaching programme).

ment tool, was used to assess participants

personality domains and facets. it includes Coaching programme

statements such as ‘When i do things, i do the step-wise process of intentional person-

them vigorously’ (facet activity), ‘i often feel ality change coaching that provided the

tense and jittery’ (facet anxiety) and ‘i’m not coaching programme framework for the

know for my generosity’ (facet altruism). current study will be discussed in detail in a

participants responded on a five-point scale separate article (Martin et al., 2014).

(0=strongly disagree, 4=strongly agree). the However, a brief overview of the step-wise

neo assesses five broad domains based on process applied is illustrated in figure 1

the five-factor Model of personality, (i.e. (overleaf).

emotionality, extraversion, openness, agree- participants in the coaching programme

ableness and conscientiousness). these five completed a neo pi-r directly before

domains provide a more general description coaching commenced, and completed addi-

of personality, whilst 30 facets allow for a tional neo pi-rs at session five (week five),

more detailed analysis. session 10 (week 10) and again three months

the neo pi-r has been validated against later (week 22). participants in the waitlist

a variety of other personality assessment control group completed a neo pi-r 10

tools, and has a acceptable level of alpha reli- weeks before coaching commenced, and

abilities (ranging from .56 to .81 for facets completed additional neo pi-rs directly

and .86 to .92 for domains), and test-retest before session one (week 10), session five

reliability (between .70 and .80 for most (week 15), session 10 (week 20) and again

facets and domains)(piedmont, 1998). three months later (week 32).

During the first coaching session, partici-

Procedure pants were provided with their personality

participants were recruited by an article in a profile, which included a description and

local newspaper, an invitation to participate graphing of five broad domains and 30 facets

posted on a university website, and word of against population norms, based on the

mouth from existing participants. the only neo pi-r (Costa & McCrae, 1992). the

initial eligibility criteria was that respondents coach facilitated discussion on whether the

be 18 years or older. subsequently, major participant would like to increase or

psychopathology was excluded by asking decrease a limited number of facets. this

those participants who had one or more discussion took into account participant

emotionality facets on the personality inven- values, motivational factors, and considera-

tory (i.e. anxiety, anger, depression, vulnera- tion of how facets helped or hindered them

bility, impulsivity or self-conscientiousness) in everyday life. if the participant chose to

in the very high range to also complete a increase or decrease one or more facets, they

Millon MCMi-iii (Millon, Davis & Millon, continued in the programme, and changing

1997), an inventory which assesses for those facets became the over-riding goal of

DSM-IV diagnoses. those individuals with the coaching. Changes on the neo pi-r

axis ii disorders, significant current alcohol scores on the participant selected facets, in

and drug abuse, active psychosis or bipolar the direction chosen by the client, became

disorder were excluded from the study, and the measure of change. a coaching manual

referred to other services. participants were provided a structured step-by-step coaching

then randomly assigned to either the person- process, and incorporated a unique set of

ality coaching group (and completed a change intervention options for each of the

10-week personality coaching programme) 30 facets. the facet change interventions

International Coaching Psychology Review l Vol. 9 No. 2 September 2014 201

AuthorS.name

Lesley Martin, Lindsay G. Oades & Peter Caputi

Figure 1: A step-wise process of intentional personality change.

Step 1: Assess personality and client values

l Complete personality inventory and develop report.

l Complete values inventory.

Step 2: Discover the current self

l Explore what is positive and problematic in the client's life.

l Review client values questionnaire findings.

l Review personality report.

Step 3: Explore gaps between the current and ideal self

l Clarify client’s ideal self.

l Reflect on how current and ideal personality differ.

l Explore what facet changes could help narrow this gap.

Step 4: Choose personality facet change goals

l Shortlist facets targeted for change.

l Review consistency of proposed changes with values.

Step 5: Assess attitudes towards change

l Assess motivation, importance, confidence and timeliness.

l Manage ambivalent attitudes and/or review change goals.

l Finalise list of facets to target for change.

Step 6: Design and implement coaching plan

l Choose change intervention options for targeted facets.

l Develop and implement a coaching plan.

Step 7: Re-assess personality and review progress

l Re-administer personality inventory (session 5).

l Review progress and revise coaching plan (if necessary).

Step 8: Implement remaining coaching sessions

l Implement remaining coaching sessions, incorporating coaching plan revisions.

Step 9: Re-assess, review and maintain

l Re-administer personality inventory (session 10).

l Review progress towards personality change goals.

l Develop a maintenance plan for targeted sub-trait change.

Step 10: Follow-up, review and refinement

l Re-administer personality inventory (three months later).

l Refine maintenence strategies for targeted facet change.

primarily reflected an eclectic mix the of intentional personality change coaching’

following approaches; solution focused (Martin et al., 2014).

coaching, positive psychology, acceptance Coaching was conducted by two regis-

and commitment principles and cognitive tered and seven provisionally registered

behavioural techniques. further informa- psychologists who received training in

tion on these steps and specific change inter- personality coaching by way of: (a) atten-

ventions, how they were developed, a client dance at a one-day workshop; (b) provision

example, and an extract from the coaching of a coach training manual, developed in a

manual are provided in ‘a step-wise process previous phase of the research; (c) comple-

202 International Coaching Psychology Review l Vol. 9 No. 2 September 2014

Intentional personality change coaching

Title

tion of a research fidelity checklist after each a graphical representation of the means for

coaching session; and (d) weekly one-hour the coaching group and waitlist group at

one-to-one supervision, which included week 1 and week 10 is presented in figure 2

review of videoed coaching sessions. (overleaf).

training and supervision was provided by:

(1) the lead researcher in the study, who Repeated measures analysis of change in ATFS

also facilitated the development of the step- over time

wise process of personality change. she was a as the logistics of having participants

registered psychologist, coach and phD complete personality inventories part way

candidate, with extensive prior experience through a waitlist period were considered

in training. (2) the Director of the univer- impractical, week 5 measures were not taken

sity psychology Clinic where the coaching for the waitlist group. However, measures

took place, who was a Clinical psychologist, were taken at week 5 during the coaching

and a psychology Board of australia period. Consequently, a repeated measures

approved supervisor. the majority of the anova was performed in order to provide

coaches (seven) were Master’s level clinical additional information regarding when

students at a regional australian university. change occurred during the coaching

four coaches were also phD candidates. the period.

Master’s level clinical students were in their assumption tests revealed no violations

fifth year of full-time training in psychology, of normality; however Mauchly’s test indi-

and had a minimum of 60 hours of prior cated that the assumption of sphericity had

face-to-face client contact. been violated. Consequently a Greenhouse-

Geisser correction was applied. the results

Results of the analysis suggested that there was

Mixed design analysis comparing waitlist to a significant difference in atfs between

coaching group on ATFS over 10 weeks time points over the coaching period,

a mixed design analysis of variance F(1.72,86.2)=36.63, p<.001, hp2=.42. Within

(anova) with Group (waitlist versus subject contrasts indicated a significant

coaching) as the between subjects factor and linear effect for time, F(1,50)=52.90, p<.001,

time (week 1 versus week 10) as the within hp2=.51.

subjects factor indicated a significant main in order to determine whether there

effect for time, F(1,51)=13.90, p<.001, were significant differences in atfs between

hp2=.21. there was a significant interaction each specific time point during the coaching

effect between Group and time period, a series of dependent sample t-tests

F(1,51)=11.27, p=.001, hp2=.18. simple were performed using a Bonferroni adjusted

effects were used to analyse the interaction significance level of .016 which was calcu-

effect. at week 1, there was no significant lated by dividing a significance level of .05 by

difference in atfs between the control the number of analyses (3). the results indi-

group (M=13.02, SD=3.58) and the coaching cated that atfs was significantly higher at

group (M=13.51, SD=3.58), F(1,51)=.23, week 5 (M=15.40, SD=3.86) as compared to

p=.63, hp2=.005. at week 10, the coaching week 1 (M=13.45, SD=3.50), t(50)=–3.98,

group had significantly higher atfs p<.001, r=.49. it was also found that scores on

(M=17.14, SD=4.67) than the control group atfs were significantly higher at week 10

(M=13.21, SD=3.34), F(1,51)=11.95, p=.001, (M=17.83, SD=4.28) as compared to week 5

hp2=.19. there was no significant simple (M=15.40, SD=3.86), t(50)=–5.70, p<.001,

effect for time for the control group, r=.62. similarly atfs was significantly higher

F(1,51)=.07, p=.79. there was a significant at week 10 (M=17.83, SD=4.28) as compared

simple effect for time for the coaching to week 1(M=13.45, SD=3.50), t(50)=–7.27,

group, F(1,51)=24.63, p<.001, hp2=.33. p<.001, r=.72.

International Coaching Psychology Review l Vol. 9 No. 2 September 2014 203

AuthorS.name

Lesley Martin, Lindsay G. Oades & Peter Caputi

Figure 2: Average targeted facet score (ATFS) for coaching versus control group over a

10-week coaching period.

a dependent samples t-test was used to t-test indicated that participants’ atfs scores

determine whether there were significant were significantly higher at the 12-week

differences between participants’ atfs at the follow-up when compared to pre-interven-

12-week follow-up as compared to the end of tion scores, t(49)=6.70, p<.001, r=.67.

the coaching period (week 10). the results of

this analysis suggested that participants Influence of age, gender and number of facets

scores on targeted personality facets had not targeted

significantly declined between week 10 a multiple regression analysis was used to

(M=17.72, SD=4.26) and the 12-week follow- determine whether age, gender and number

up (M=17.79, SD=4.71), t(49)=–.25, p=.80. of facets targeted significantly predicted

furthermore, a second dependent samples change in atfs over the intervention

204 International Coaching Psychology Review l Vol. 9 No. 2 September 2014

Intentional personality change coaching

Title

period. the results suggested that these support for spence and Grant’s (2005) tenta-

factors accounted for 3.7 per cent of the vari- tive findings that personality changes may

ance which was non-significant, R 2=.10, occur during 10 weeks of coaching (even

F(1,49)=1.65, p=.19. the results of the when personality change is not the goal of

regression analysis are summarised in table coaching). the stronger findings in the

3 below. current study on personality change (relative

to spence and Grant’s findings) are likely

Discussion attributable to personality change being

the results support the hypothesis that targeted with interventions designed for this

personality change coaching can facilitate purpose (i.e. spence and Grant only found

significant change in participant selected changes on two of five domains, and with peer

facets, in the direction desired by the parti- coaching only).

cipant. the significant changes achieved the current study’s findings provide

between sessions 1 and 5, and again between empirical support for the proposition that

session 5 and 10 suggest that meaningful targeted personality change coaching can

changes occur relatively early in the facilitate change on targeted facets, if the

coaching process, and are further consoli- participant is motivated to change. it also

dated by additional sessions. the incre- provides empirical support for the step-wise

mental pattern of these changes raises the process of intentional personality change

question of whether further personality proposes by Martin, oades and Caputi

change would be achieved by additional (2014). in so doing, it affirms the value of a

sessions of coaching. structured coaching process, using resources

the findings of significant change in specifically designed for this purpose.

personality are in contrast with some litera- the finding that gender does not affect

ture that proposes that personality is relatively personality change outcomes may have been

resistant to change without long-term inten- influenced by the small number of men

sive interventions (e.g. McCrae & Costa, 1994, (N=8) participating in the study, and further

2003). However, the current study’s finding exploration of this question with larger male

are consistent with other literature (predomi- samples would be useful. no participants

nantly published in the last five years) that over 65 years enrolled in the study, leaving

suggests that personality is more amenable to this age group unexplored. However, in the

change than was previously thought (Boyce et 18 to 64 years age range enrolled in the

al., 2012; De fruyt et al., 2006; Dweck, 2008; study, age did not significantly affect capacity

Jackson et al., 2012; Martin et al., 2012; nelis to change. this is encouraging as it suggests

et al., 2011; orme-Johnson & Barnes, 2013; that intentional personality change can be

robinson, 2009; tang et al., 2009). from a achieved by motivated individuals through-

coaching perspective, it provides further out most, if not all, of the adult lifespan.

Table 3: Influence of age, gender and number of facets targeted on change in

Averaged Targeted Facet Score (ATFS).

Variable B SE B b p

Constant 7.06 3.75

Number of facets targeted .68 .39 .24 .09

Age -.01 .05 –.02 .90

Gender -2.43 1.63 –.21 .14

International Coaching Psychology Review l Vol. 9 No. 2 September 2014 205

AuthorS.name

Lesley Martin, Lindsay G. Oades & Peter Caputi

the number of facets targeted did not possibility is supported by a number of

significantly predict change in atfs. this is studies that suggests that a range of inter-

somewhat surprising as it might be expected ventions (not specifically targeting person-

that focusing on just one or two facets over ality change) nevertheless may have wide

10 sessions would achieve greater average ranging beneficial impacts on personality

change on targeted facets than focusing on (nelis et al., 2011; piedmont, 2001; tang et

five or six facets, as each targeted facet would al., 2009).

have a greater number of coaching hours the findings of the current study are

available to work on it. for example, relevant to the literature in a number of

targeting just one facet would mean that 10 areas. from a coaching perspective, it

hours of coaching could be available to facil- provides preliminary empirical validation of

itate change on it, whereas if five facets were the step-wise process outlined in Martin,

targeted each of these targeted facets would oades and Caputi (2014) and suggests that

only have two hours, on average, applied to structured coaching may be an effective

changing them. one possible explanation mechanism for facilitating beneficial person-

for this result is that participants who are ality change in motivated individuals. the

experiencing greater dissatisfaction with preliminary validation of coaching as an

their personality may well target more facets, effective personality change process has

but may also have more scope for movement significant implications for the coaching

on facets targeted. similarly, individuals who profession, as it extends coaching practice

are functioning well may only wish to make and research into a new and potentially

minor changes to one or two facets. Hence exciting arena. it also raises questions about

the beneficial effects of more hours of the skills needed to competently undertake

coaching per facet for participants with less this work. training in personality, psycho-

problematic personalities may be offset by a metrics, and coaching, plus the capacity to

floor/ceiling effect. this ties in with the find- work competently with psychological

ings of orme-Johnson and Barnes (2013) distress, are likely to be important skills.

that those individuals with higher levels of the findings of this study also raise ques-

anxiety benefitted most from a meditation tions around the circumstances in which

intervention. personality change interventions are appro-

an alternative possibility is that interven- priate. it is the authors’ opinion that if

tions that target one problematic facet may personality change coaching were to be

also trigger changes on other problematic conducted in the absence of participant

facets. for example, if someone is low on motivation to change aspects of their person-

self-discipline and high on anxiety, then ality, it would likely be ineffectual, and could

increasing self-discipline (e.g. through be ethically problematic. Hence further

enhancing planning and organisational exploration of, and debate around, how and

skills) may in turn reduce anxiety (e.g. if personality change coaching fits within an

through reducing distress around the conse- organisational coaching context would be

quences of procrastination). similarly, devel- beneficial (e.g. where an organisations may

opment of certain facet change skills (e.g. be concerned about problematic personality

challenging unhelpful beliefs and assump- facets/domains in a staff member).

tions, and learning to think in a more posi- from the perspective of personality liter-

tive and realistic way) may beneficially affect ature, the current study provides further

many facets. for example, cognitive support for the plasticity of personality, and

behavioural interventions designed to preliminary empirical support for partici-

reduce facet depression may have a benefi- pant selected intentional personality change.

cial effect on other targeted facets (e.g. the capacity to intentionally change person-

anxiety, gregariousness, assertiveness). this ality has implications from a number of

206 International Coaching Psychology Review l Vol. 9 No. 2 September 2014

Intentional personality change coaching

Title

perspectives. firstly, the strong relationship cations for the findings of the current study.

between personality and well-being (Boyce for example, participants in the current

et al., 2012) suggests that intentional person- study were predominantly women, and the

ality change coaching may potentially also possible impact of this on outcomes deserves

have a significant impact on well-being. further attention. future studies using a

future research directly exploring whether more gender balanced sample, or a male

intentional personality change coaching only sample, would be useful. analysis of

results in changes in well-being would participant personalities at the commence-

usefully inform both the personality and ment of coaching suggested that certain

well-being literature. types of personalities chose to change their

furthermore, the capacity to change personality (e.g. those high on openness and

personality suggests a host of potential bene- emotionality) (allan, Leeson & Martin,

ficial implications at the individual, interper- 2014). this may suggest that the findings of

sonal and organisational/community level. this study are relevant to certain groups of

Based on the associations found between individuals, rather than the general popula-

personality and consequential outcomes by tion.

ozer and Benet-Martinez (2006), modifying furthermore, assessment of change was

personality could potentially have a benefi- limited to self-report inventories with the

cial impact on the following: spirituality, inherent risks of (e.g. faking good and

physical and mental health, longevity, self- responses being influenced by the goals of

concept and identity at the individual level; the coaching). Whereas personality ratings

peer, family and romantic relationships at by others are informative and desirable in

the interpersonal level; and a range of occu- many contexts, it was considered less rele-

pational and community outcomes. the vant in the current study. the current study

current research responds to a need, was focused on changing facets consistent

expressed in the literature, to move beyond with the participant’s desire for change,

understanding what the consequential rather than meeting others’ perceptions of,

impacts of personality are, to exploring if or preference for, observable change.

and how beneficial personality change can furthermore, it is difficult for others to accu-

be facilitated (e.g. Boyce et al., 2012; rately assess change on some facets (e.g.

Cuijpers et al., 2010; Hampson, 2012). fantasy, ideas). nevertheless, this is a signifi-

a number of limitations of the current cant limitation, and one that would benefit

study should be considered when inter- from future studies incorporating additional

preting the findings. this study is a prelimi- measures (e.g. informant reports and

nary investigation, using a relatively small behavioural assessments). it is further

sample size. strong claims cannot be made acknowledged that repeated administration

on the basis of a single study of this size, of a questionnaire may impact responses.

suggesting further empirical studies of this the current study followed participants

nature would be useful. furthermore, this for three months after completion of the

study is based on just one construct of research; hence longer-term outcomes are

personality (the five-factor Model of not know. future research of intentional

personality), and one measure (i.e. the neo personality change, with longer follow up

pi-r self report). periods, would further inform the literature.

participants were self-selected, and may finally, whereas it is useful to know if person-

not be representative of the general popula- ality change was achieved based on inventory

tion. researchers, including the first author, scores, the current study does not link these

are currently exploring the gender, age and changes to consequential tangible life

personality of individuals who chose to outcomes. Whereas associations between

change their personality, and possible impli- personality measures and a wide range of

International Coaching Psychology Review l Vol. 9 No. 2 September 2014 207

AuthorS.name

Lesley Martin, Lindsay G. Oades & Peter Caputi

consequential outcomes is well established The Authors

(e.g. ozer & Benet-Martinez, 2006), it is Lesley S. Martin

unclear whether intentionally changing sydney Business school,

personality will lead to changes in these university of Wollongong.

outcomes (i.e. at this stage cause and effect is

not clear). in combination, these limitations Lindsay G. Oades

suggest that the current study’s findings australian institute of Business Wellbeing,

should be viewed as preliminary. Hence, sydney Business school,

future studies addressing these limitations university of Wollongong.

would be useful. researchers, including the

first author, are currently exploring partici- Peter Caputi

pants’ experiences of personality coaching, school of psychology,

including the tangible life impacts of inten- university of Wollongong.

tional personality change coaching (Martin

et al., in press). Correspondence

in conclusion, the current study provides Lesley Martin

preliminary support for the proposition that po Box 5059,

intentional personality change, facilitated by Wollongong, nsW 2500,

a structured step-wise coaching process, is australia.

possible. as personality is predictive of a email: sue@psy.net.au

wide range of life outcomes, exciting possi-

bilities are evident in the potential of inten-

tionally changing personality. these findings

provide a novel and important contribution

to literature in the fields of personality,

coaching and intentional change. they also

inform coaching practitioners, and sugges-

tion new opportunities for coaches with rele-

vant skills. it is hoped that the current study

will provide an important foundation for

future exploration in this area, and a useful

beginning in understanding if intentional

personality change is possible, and how it

can best be achieved.

208 International Coaching Psychology Review l Vol. 9 No. 2 September 2014

Intentional personality change coaching

Title

References

allan, J.a., Leeson, p. & Martin, L.s. (2014). Who Martin, L.s., oades, L.G. & Caputi, p. (2012). What is

wants to change their personality and how do they personality change coaching and why is it

want to change it? International Coaching Psychology important? International Coaching Psychology Review,

Review, 9(1), 8–21. 7, 185–193.

Boyce, C.J., Wood, a.M. & powdthavee, n. (2012). Martin, L.s., oades, L.G. & Caputi, p. (in press).

is personality fixed? personality changes as much Clients’ experiences of intentional personality

as ‘variable’ economic factors and more strongy change coaching. International Coaching Psychology

predicts changes to life satisfaction. Social Review.

Indicators Research. retrieved 7 november 2012, McCrae, r. & Costa, p.t., Jr. (1994). the stability of

from: personality: observation and evaluations. Current

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/ Directions in Psychological Science, 3, 173–175.

s11205-012-0006-z#page-1 McCrae, r. & Costa, p.t., Jr. (2003). Personality in

Costa, p.t. & McCrae, r.M. (1992). Revised NEO adulthood: A five-factor theory perspective (2nd. ed.).

Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor new York: Guilford press.

Inventory (NEO FFI). Lutz, fL: psychological Millon, t., Davis, r. & Millon, C. (1997). MCMI–III

assessment resources, inc. Manual (2nd ed.). Minneapolis, Mn: national

Cuijpers, p., smit, f., penninx, B., de Graaf, r., ten Comptuer systems, inc.

Have, M. & Beekman, a. (2010). economic costs nelis, D., Kotsou, i., Quoidbach, J., Hansenne, M.,

of neuroticism: a population-based study. Archives Weytens, f., Dupuis, p. & Mikolajczak, M. (2011).

of General Psychiatry, 67, 1086–1093. increasing emotional competence improves

De fruyt, f., van Leeuwen, K., Bagby, r.M., rolland, J. psychological and physical well-being, social

& rouillon, f. (2006). assessing and interpreting relationships, and employability. Emotion, 11,

personality change and continuity in patients 354–366.

treated for major depression. Psychological orme-Johnson, D.W. & Barnes, v.a. (2013). effects of

Assessment, 18, 71–80. transcendental meditation technique on trait

Dweck, C.s. (2008). Can personality be changed? anxiety: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled

Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17, trials. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary

391–394. Medicine, 19, 1–12.

Green, L.s., Grant, a.M. & rynsaardt, J. (2007). ozer, D.J. & Benet-Martinez, v. (2006). personality

evidence-based life coaching for senior high and the prediction of consequential outcomes.

school students: Building hardiness and hope. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 401–421.

International Coaching Psychology Review, 2, 24–32. piedmont, r.L. (1998). The Revised NEO Personality

Hampson, s.e. (2012). personality processes: Inventory: Clinical and research applications.

Mechanisms by which personality traits ‘get new York: plenum press.

outside the skin’. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, piedmont, r.L. (2001). Cracking the plaster cast:

315–339. Big 5 personality change during intensive

Jackson, J.J., Hill, p.L., payne, B.r., roberts, B.W. & outpatient counseling. Journal of Research in

stine-Morrow, e.a.L. (2012). Can an old dog Personality, 35, 500–520.

learn (and want to experience) new tricks? spence, G.B. & Grant, a.M. (2005). individual and

Cognitive training increases openness to group life-coaching: initial findings from a

experience in older adults. Psychology and Aging, randomised, controlled trial. in M. Cavanagh,

27, 286–292. a.M. Grant & t. Kemp (eds.), Evidence-based

Magidson, J.f., roberts, B.W., Collado-rodriguez, a. coaching (vol. 1, pp.143–158). Bowen Hills,

& Lejuez, C.W. (2012). theory-driven inter- australia: australian academic press.

vention for changing personality: expectancy spence, G.B. & Grant, a.M. (2007). professional and

value theory, behavioral activation, and peer life coaching and the enhancement of goal

conscientiousness. Developmental Psychology, striving and well-being: an exploratory study.

advance online publication. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2, 185–194.

doi: 10.1037/a0030583. tang, t.Z., Derubeis, r.J., Hollon, s.D., amsterdam,

Martin, L.s., oades, L. & Caputi, p. (2014). a step-wise J., shelton, r. & schalet, B. (2009). personality

process of intentional personality change coach- change during depression treatment. Archives of

ing. International Coaching Psychology Review, 9(2), General Psychiatry, 66, 1322–1330.

55–69.

International Coaching Psychology Review l Vol. 9 No. 2 September 2014 209

Copyright of International Coaching Psychology Review is the property of British

Psychological Society and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted

to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may

print, download, or email articles for individual use.

View publication stats

You might also like

- Exploring What It Effectively Means to Manage Carpal Tunnel Syndrome’S: Physical, Social, and Emotional Crucibles in a Return to Work ProgramFrom EverandExploring What It Effectively Means to Manage Carpal Tunnel Syndrome’S: Physical, Social, and Emotional Crucibles in a Return to Work ProgramNo ratings yet

- A Step-Wise Process of Intentional Personality Change CoachingDocument16 pagesA Step-Wise Process of Intentional Personality Change Coachinggenerico2551No ratings yet

- A Complex Dynamic Systems Approach To Lasting Positive Change The Synergistic Change ModelDocument14 pagesA Complex Dynamic Systems Approach To Lasting Positive Change The Synergistic Change ModelChesha LEVNo ratings yet

- Personality change - Nguyễn Hương Giang - 1911140009Document4 pagesPersonality change - Nguyễn Hương Giang - 1911140009Huong GiangNo ratings yet

- Student WPQ QuestionnaireDocument15 pagesStudent WPQ Questionnaireluis filipeNo ratings yet

- FINAL Strengths Based InterventionsDocument20 pagesFINAL Strengths Based InterventionsHeyssel WittersheimNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument16 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptAsriatul AiniNo ratings yet

- BRM Paper Findings 2Document4 pagesBRM Paper Findings 2aakash.sachan.23mbNo ratings yet

- Bornstein 2016Document12 pagesBornstein 2016castomNo ratings yet

- SubjectiveWell BeingDocument13 pagesSubjectiveWell Beinghafsa fatimaNo ratings yet

- The Third Wave of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and The Rise of Process - Based CareDocument3 pagesThe Third Wave of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and The Rise of Process - Based CareMaria MartinezNo ratings yet

- J Neubiorev 2020 03 017Document52 pagesJ Neubiorev 2020 03 017Helena QuintNo ratings yet

- Personal I DadeDocument18 pagesPersonal I DadeRenata CoelhoNo ratings yet

- Systematic ReviewDocument17 pagesSystematic ReviewVivien IacobNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness Study Article On Psychodynamic PsychotherapyDocument10 pagesEffectiveness Study Article On Psychodynamic PsychotherapyRiham AmmarNo ratings yet

- Personality Trait Stability and Change Author Wiebke Bleidorn and OthersDocument20 pagesPersonality Trait Stability and Change Author Wiebke Bleidorn and OthersMujb RehmanNo ratings yet

- WorldPsychiatryHayes Hofmann 2017Document3 pagesWorldPsychiatryHayes Hofmann 2017Stefano RobertoNo ratings yet

- Expressive Writing An Alternative To Traditional MDocument25 pagesExpressive Writing An Alternative To Traditional Mbobita2004No ratings yet

- Lundahl2009 - The Effectivenes of Motivational InterviewingDocument14 pagesLundahl2009 - The Effectivenes of Motivational InterviewingBruno AlencarNo ratings yet

- The Relation of Negative Career Thoughts To Depression and Hopelessness (2017)Document14 pagesThe Relation of Negative Career Thoughts To Depression and Hopelessness (2017)ranti faqothNo ratings yet

- Positive Perspectives Matter Enhancing Positive Organizational BehaviorDocument15 pagesPositive Perspectives Matter Enhancing Positive Organizational BehaviorGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Stirman CPSP 2017Document26 pagesStirman CPSP 2017Link079No ratings yet

- Happiness Is Everything, or Is It Explorations On The Meaning of Psychological Well-BeingDocument13 pagesHappiness Is Everything, or Is It Explorations On The Meaning of Psychological Well-BeingKiklefou100% (2)

- Third Wave Rise of Process Based CareDocument2 pagesThird Wave Rise of Process Based CareSidarta RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Environmental Crisis and Human Well-Being: A Review: Lalatendu Kesari Jena, Bhagirath BeheraDocument14 pagesEnvironmental Crisis and Human Well-Being: A Review: Lalatendu Kesari Jena, Bhagirath BeheraJan Karina Lapeña PadlaNo ratings yet

- Functional Analysis Is Dead, Long Live Functional AnalysisDocument5 pagesFunctional Analysis Is Dead, Long Live Functional AnalysisA. AlejandroNo ratings yet

- Ojmp 2017042014531763Document10 pagesOjmp 2017042014531763Anovy RarumNo ratings yet

- 13.1 Pennebaker1997 WritingemotionalexperiencesDocument6 pages13.1 Pennebaker1997 Writingemotionalexperienceselttil2lrig2384No ratings yet

- The Reliability and Factorial Validity of The Swedish Version of The Recovery Experience QuestionnaireDocument11 pagesThe Reliability and Factorial Validity of The Swedish Version of The Recovery Experience QuestionnairePriyashree RoyNo ratings yet

- Motivation and Behaviour ChangeDocument16 pagesMotivation and Behaviour ChangeAllen Joshua GantiNo ratings yet

- Comparing Counseling and Clinical Psychology Practitioners Similarities and Differences On Theoretical Orientations RevisitedDocument12 pagesComparing Counseling and Clinical Psychology Practitioners Similarities and Differences On Theoretical Orientations RevisitedGeorges El NajjarNo ratings yet

- Change Process Research in PsychotherapyDocument19 pagesChange Process Research in PsychotherapyJuanaNo ratings yet

- Towards An Integrative Model of Sources of Personality Stability and ChangeDocument17 pagesTowards An Integrative Model of Sources of Personality Stability and ChangeThiago MontalvãoNo ratings yet

- An Examination of The Effectiveness of Dialectical Behavior Therapy Skills GroupsDocument10 pagesAn Examination of The Effectiveness of Dialectical Behavior Therapy Skills Groupsluisa paola sanchez sarmientoNo ratings yet

- ERQ Study Manuscript ACCEPTEDDocument30 pagesERQ Study Manuscript ACCEPTEDmarcelocarvalhoteacher2373No ratings yet

- Conscientiousness and Healthy Aging: Workshop Report IDocument18 pagesConscientiousness and Healthy Aging: Workshop Report IMihaelaSiVictoriaNo ratings yet

- Psychiatry Research: A A B C A A A DDocument7 pagesPsychiatry Research: A A B C A A A DArif IrpanNo ratings yet

- MindfulnessandProsocialMeta Prepublication DraftDocument49 pagesMindfulnessandProsocialMeta Prepublication DraftIhjaskjhdNo ratings yet

- Salminen 2017Document9 pagesSalminen 2017kirantiNo ratings yet

- Selff Determination TheoryDocument102 pagesSelff Determination TheoryannibabzNo ratings yet

- Literature Review DBTDocument5 pagesLiterature Review DBTc5kgkdd4100% (1)

- Psychological Hardiness Final DraftDocument15 pagesPsychological Hardiness Final DraftMousa AhmedNo ratings yet

- Group Cognitive Behavioural Therapy For Psychosis in The Asian Context: A Review of The Recent StudiesDocument28 pagesGroup Cognitive Behavioural Therapy For Psychosis in The Asian Context: A Review of The Recent StudiesIka Agitra NingrumNo ratings yet

- Exercise As A Treatment For Depression - A Meta-Analysis Adjusting For Publication Bias PDFDocument11 pagesExercise As A Treatment For Depression - A Meta-Analysis Adjusting For Publication Bias PDFSlick RaulNo ratings yet

- Mediation Moderation in Social Psychological ResearchDocument11 pagesMediation Moderation in Social Psychological ResearchLiao Nukelan Yuntsai NeetuNo ratings yet

- Behavioral Activation InterventionsDocument18 pagesBehavioral Activation InterventionsAlvinNo ratings yet

- Major Research Findings - CFM - UMass Medical School - WorcesterDocument2 pagesMajor Research Findings - CFM - UMass Medical School - WorcesterJack LiuNo ratings yet

- Extraversion As A Moderator of The Efficacy of Self-Esteem Maintenance StrategiesDocument15 pagesExtraversion As A Moderator of The Efficacy of Self-Esteem Maintenance StrategiesHusnie Al-mubarok AfandieNo ratings yet

- Vandierendonck2004 PDFDocument15 pagesVandierendonck2004 PDFjunk jinkNo ratings yet

- Psychological Formulation As An Alternative To Psychiatric Diagnosis 2017Document18 pagesPsychological Formulation As An Alternative To Psychiatric Diagnosis 2017Alejandra ClarosNo ratings yet

- The Joint Roles of Career Decision Self-Efficacy and Personality Traits in The Prediction of Career Decidedness and Decisional DifficultyDocument14 pagesThe Joint Roles of Career Decision Self-Efficacy and Personality Traits in The Prediction of Career Decidedness and Decisional DifficultyNgọc TrânNo ratings yet

- Does Expressive Writing Reduce Stress and Improve Health For Family Caregivers of Older Adults?Document11 pagesDoes Expressive Writing Reduce Stress and Improve Health For Family Caregivers of Older Adults?api-193771047No ratings yet

- Emotional Regulation and Interpersonal Effectiveness As Mechanisms of Change For Treatment Outcomes Within A DBT Program For AdolescentsDocument13 pagesEmotional Regulation and Interpersonal Effectiveness As Mechanisms of Change For Treatment Outcomes Within A DBT Program For AdolescentsLauraLoaizaNo ratings yet

- Mindfulness-Based Treatment For Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review of The LiteratureDocument27 pagesMindfulness-Based Treatment For Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review of The LiteratureFilza RamdhaniNo ratings yet

- 2018 Article DifferentialTreatmentMechanismDocument13 pages2018 Article DifferentialTreatmentMechanismRuslan SolowatNo ratings yet

- Kroencke Et Al 2020 How Does Substance Use Affect Personality Development Disentangling Between and Within PersonDocument11 pagesKroencke Et Al 2020 How Does Substance Use Affect Personality Development Disentangling Between and Within Personcarllaurenceaquino53No ratings yet

- Mindfulness Meditation and PsychopathologyDocument37 pagesMindfulness Meditation and Psychopathologydyg dygNo ratings yet

- 1998 Self EfficacyQuestionnaireforSchoolSituationsDocument12 pages1998 Self EfficacyQuestionnaireforSchoolSituationsFahmi FajarNo ratings yet

- Kerr2015 Article CanGratitudeAndKindnessInterveDocument20 pagesKerr2015 Article CanGratitudeAndKindnessInterveAdnan ZahidNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Effects of Psychedeli - Jacob S. AdayDocument11 pagesLong-Term Effects of Psychedeli - Jacob S. AdaysilentrevoNo ratings yet

- PH Festival Detailed Lesson PlanDocument13 pagesPH Festival Detailed Lesson PlanMira Magpili50% (2)

- Landon AlexanderDocument6 pagesLandon Alexanderapi-455881201No ratings yet

- Self Hypnosis: Hypnosis and The Unconscious MindDocument6 pagesSelf Hypnosis: Hypnosis and The Unconscious MindSai BhaskarNo ratings yet

- Reconfigurable Diffractive Antenna Based On Switchable Electrically Induced TransparencyDocument12 pagesReconfigurable Diffractive Antenna Based On Switchable Electrically Induced TransparencyAnuj SharmaNo ratings yet

- Who We Are Jan 8 2013Document5 pagesWho We Are Jan 8 2013api-147600993No ratings yet

- Law Student Government: Ateneo de Naga UniversityDocument1 pageLaw Student Government: Ateneo de Naga UniversityFbarrsNo ratings yet

- Higher Education Book CompleteDocument204 pagesHigher Education Book Completetilak kumar vadapalliNo ratings yet

- CBSE Class 6 Mathematics Sample Paper Set G - 0Document3 pagesCBSE Class 6 Mathematics Sample Paper Set G - 0ik62299No ratings yet

- Gujarat Cbse SchoolDocument47 pagesGujarat Cbse Schoolramansharma1769No ratings yet

- Performance Appraisal Wording ExamplesDocument6 pagesPerformance Appraisal Wording ExamplesHarry olardoNo ratings yet

- Comparing Numbers (2021 - 06 - 19 01 - 35 - 12 UTC) (2021 - 08 - 06 04 - 51 - 25 UTC)Document3 pagesComparing Numbers (2021 - 06 - 19 01 - 35 - 12 UTC) (2021 - 08 - 06 04 - 51 - 25 UTC)ALLinOne BlogNo ratings yet

- School Nursing SyllabusDocument4 pagesSchool Nursing SyllabusFirenze Fil100% (1)

- Arduino Light Sensor: PROJECT WORK (BCA - 409: Semester V) Robopedia-1Document6 pagesArduino Light Sensor: PROJECT WORK (BCA - 409: Semester V) Robopedia-1Panchal MineshNo ratings yet

- Musa AbubakarDocument3 pagesMusa AbubakarsadiqNo ratings yet

- EDPM Mark Scheme SBA Assignment 2 - 2017Document1 pageEDPM Mark Scheme SBA Assignment 2 - 2017ocamp200750% (2)

- Cot - English 4-Q4-WK 10-Gary C. RodriguezDocument5 pagesCot - English 4-Q4-WK 10-Gary C. Rodriguezjerick de la cruzNo ratings yet

- NCP Impaired Social InteractionDocument2 pagesNCP Impaired Social InteractionKristian Karl Bautista Kiw-isNo ratings yet

- (the History and Theory of International Law) Stefan Kadelbach, Thomas Kleinlein, David Roth-Isigkeit-System, Order, And International Law_ the Early History of International Legal Thought From MachiaDocument545 pages(the History and Theory of International Law) Stefan Kadelbach, Thomas Kleinlein, David Roth-Isigkeit-System, Order, And International Law_ the Early History of International Legal Thought From MachiaGilberto Guerra100% (2)

- Course Material (Lecture Notes) : Sri Vidya College of Engineering & TechnologyDocument29 pagesCourse Material (Lecture Notes) : Sri Vidya College of Engineering & TechnologyNivas JNo ratings yet

- Cell Division Lab ReportDocument9 pagesCell Division Lab ReportBrianNo ratings yet

- Top 25 Test-Taking Tips, Suggestions & Strategies: WrongDocument5 pagesTop 25 Test-Taking Tips, Suggestions & Strategies: WronglheanzNo ratings yet

- 9,11 CBSE and 9 KB-28febDocument10 pages9,11 CBSE and 9 KB-28febsaoud khanNo ratings yet

- 10-15'-ĐỀ CHẴNDocument2 pages10-15'-ĐỀ CHẴNSơn HoàngNo ratings yet

- Psychology Research Paper AppendixDocument6 pagesPsychology Research Paper Appendixzrpcnkrif100% (1)

- Japan: Geography and Early HistoryDocument29 pagesJapan: Geography and Early HistoryXavier BurrusNo ratings yet

- G8 - Q1 - Slem - 4.1 Sound Gallego Approvedformat 1Document11 pagesG8 - Q1 - Slem - 4.1 Sound Gallego Approvedformat 1Juliana RoseNo ratings yet

- JS Promenade ScriptDocument4 pagesJS Promenade ScriptMary Joy BienNo ratings yet

- DAILY LESSON PLAN Oral Com Speech Context Q1Document5 pagesDAILY LESSON PLAN Oral Com Speech Context Q1Datu George100% (1)

- (Or How Blah-Blah-Blah Has Gradually Taken Over Our Lives) Dan RoamDocument18 pages(Or How Blah-Blah-Blah Has Gradually Taken Over Our Lives) Dan RoamVictoria AdhityaNo ratings yet

- Excretion and HomeostasisDocument31 pagesExcretion and HomeostasiscsamarinaNo ratings yet