Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sieber 2018

Uploaded by

t88frb5kqrCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sieber 2018

Uploaded by

t88frb5kqrCopyright:

Available Formats

Research

JAMA Surgery | Original Investigation

Effect of Depth of Sedation in Older Patients Undergoing

Hip Fracture Repair on Postoperative Delirium

The STRIDE Randomized Clinical Trial

Frederick E. Sieber, MD; Karin J. Neufeld, MD, MPH; Allan Gottschalk, MD, PhD; George E. Bigelow, PhD; Esther S. Oh, MD; Paul B. Rosenberg, MD;

Simon C. Mears, MD; Kerry J. Stewart, EdD; Jean-Pierre P. Ouanes, DO; Mahmood Jaberi, MD; Erik A. Hasenboehler, MD; Tianjing Li, PhD;

Nae-Yuh Wang, PhD

Invited Commentary

IMPORTANCE Postoperative delirium is the most common complication following major page 996

surgery in older patients. Intraoperative sedation levels are a possible modifiable risk factor Supplemental content

for postoperative delirium.

CME Quiz at

jamanetwork.com/learning

OBJECTIVE To determine whether limiting sedation levels during spinal anesthesia reduces and CME Questions page

incident delirium overall. 1068

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS This double-blind randomized clinical trial (A Strategy to

Reduce the Incidence of Postoperative Delirum in Elderly Patients [STRIDE]) was conducted

from November 18, 2011, to May 19, 2016, at a single academic medical center and included a

consecutive sample of older patients (ⱖ65 years) who were undergoing nonelective hip

fracture repair with spinal anesthesia and propofol sedation. Patients were excluded for

preoperative delirium or severe dementia. Of 538 hip fractures screened, 225 patients

(41.8%) were eligible, 10 (1.9%) declined participation, 15 (2.8%) became ineligible between

the time of consent and surgery, and 200 (37.2%) were randomized. The follow-up included

postoperative days 1 to 5 or until hospital discharge.

INTERVENTIONS Heavier (modified observer’s assessment of sedation score of 0-2) or lighter

(observer’s assessment of sedation score of 3-5) propofol sedation levels intraoperatively.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Delirium on postoperative days 1 to 5 or until hospital

discharge determined via consensus panel using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders (Fourth Edition, Text Revision) criteria. The incidence of delirium was compared

between intervention groups with and without stratification by the Charlson comorbidity

index (CCI).

RESULTS Of 200 participants, the mean (SD) age was 82 (8) years, 146 (73%) were women,

194 (97%) were white, and the mean (SD) CCI was 1.5 (1.8). One hundred participants each

were randomized to receive lighter sedation levels or heavier sedation levels. A good

separation of intraoperative sedation levels was confirmed by multiple indices. The overall

incident delirium risk was 36.5% (n = 73) and 39% (n = 39) vs 34% (n = 34) in heavier and

lighter sedation groups, respectively (P = .46). Intention-to-treat analyses indicated no

statistically significant difference between groups in the risk of incident delirium (log-rank

test χ2, 0.46; P = .46). However, in a prespecified subgroup analysis, when stratified by CCI,

sedation levels did effect the delirium risk (P for interaction = .04); in low comorbid states

(CCI = 0), heavier vs lighter sedation levels doubled the risk of delirium (hazard ratio, 2.3;

95% CI, 1.1- 4.9). The level of sedation did not affect delirium risk with a CCI of more than 0.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE In the primary analysis, limiting the level of sedation provided Author Affiliations: Author

affiliations are listed at the end of this

no significant benefit in reducing incident delirium. However, in a prespecified subgroup article.

analysis, lighter sedation levels benefitted reducing postoperative delirium for persons with a

Corresponding Author: Frederick E.

CCI of 0. Sieber, MD, Department of

Anesthesiology and Critical Care

TRIAL REGISTRATION clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00590707 Medicine, Johns Hopkins Bayview

Medical Center, 4940 Eastern Ave,

JAMA Surg. 2018;153(11):987-995. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2602 Baltimore, MD 21224 (fsieber1@jhmi

Published online August 8, 2018. .edu).

(Reprinted) 987

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by a Tulane University User on 01/17/2019

Research Original Investigation Effect of Depth of Sedation in Older Patients Undergoing Hip Fracture Repair on Postoperative Delirium

P

ostoperative delirium (PD) is the most common com-

plication after major surgery in older patients without Key Points

cognitive impairment.1 Postoperative delirium carries

Question Does limiting sedation levels during hip fracture repair

with it personal, social, and economic burdens.2 This compli- under spinal anesthesia reduce postoperative delirium overall or

cation, with its associated costs, will assume increasing im- when stratified by baseline comorbidity?

portance as the number of older patients in the US popula-

Findings In this randomized clinical trial that included 200 older

tion continues to grow.

patients randomized to receive lighter vs heavier sedation, limiting

The mainstay of delirium management is prevention by levels of sedation provided no significant overall benefit in

control and/or elimination of modifiable risk factors. One such reducing incident delirium. However, in a prespecified subgroup

risk factor may be sedative medications, as both drug selec- analysis, heavier vs lighter sedation levels doubled the risk of

tion and dosage can be modified. The role of sedative and an- postoperative delirium in patients with low baseline comorbidities

algesic medications as iatrogenic risk factors for delirium in in- as defined by a Charlson comorbidity index score of 0.

tensive care unit (ICU) and postsurgical patients is well Meaning Limiting intraoperative sedation levels may reduce

described.3-6 The evidence suggests that the level of sedation delirium in older patients with low baseline comorbidity.

varies substantially during surgery and that heavier sedation

levels that are consistent with general anesthesia are com-

monplace intraoperatively.7 Managing intraoperative seda- failure, (4) refusal to give informed consent, (5) a nonpartici-

tion may be an important modifiable risk factor; however, to pating attending surgeon, (6) hip fractures in both hips at the

our knowledge, few studies have been done in this area. same admission, (7) a repair of another fracture concurrently

To help explain the contribution of sedation levels to PD, with the hip fracture, (8) a prior hip surgery on the same hip

we undertook a randomized, 2-group, parallel superiority trial that would be repaired in the current surgery, and (9) preop-

called A Strategy to Reduce the Incidence of Postoperative De- erative delirium.

lirium in Elderly Patients (STRIDE). The primary aim of STRIDE

was to compare the effect of lighter and heavier intraopera- Outcomes

tive propofol sedation levels on delirium incidence in older pa- Patients were assessed for delirium, delirium severity, and cog-

tients who were undergoing hip fracture repair. A secondary nition preoperatively and on postoperative days 1 to 5 by re-

objective was a prespecified subgroup analysis to determine search personnel who were masked to the randomization as-

whether limiting sedation levels during spinal anesthesia re- signment. The diagnosis of delirium was made by a

duces incident PD when stratified by baseline comorbidity. multidisciplinary consensus panel based on Diagnostic and Sta-

tistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) criteria

using several data sources, including the confusion assess-

ment method,11 the Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-98 (DRS),12

Methods digit span, a review of medical records, and family/nursing staff

Study Design and Participants interviews. The primary outcome was the incidence of de-

The research protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins in- lirium from postoperative day 1 to postoperative day 5 or hos-

stitutional review board (NA_00041873). The trial was regis- pital discharge, whichever occurred first. The secondary out-

tered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00590707) (Supplement 1). All comes were MMSE scores and DRS severity and total scores

participants provided their written informed consent. STRIDE during the first 5 postoperative days or until hospital dis-

was conducted at a single clinical center, and all intraoperative charge, whichever occurred first. The prespecified secondary

management was provided by 4 anesthesiologists. A detailed objective was to assess the interaction between baseline co-

description of the trial protocol was published previously in morbidity and propofol sedation levels in determining de-

the supplemental material of Li et al.8 lirium incidence after hip fracture repair (see the protocol in

Patients who were 65 years or older who were undergo- the supplemental material of Li et al8).

ing hip fracture repair with spinal anesthesia and propofol se- STRIDE was powered to detect a 48.0% risk reduction in

dation and who did not have preoperative delirium or severe the primary outcome, PD in-hospital up to day 5 after sur-

dementia were randomized to receive either heavier (modi- gery, from 39.6% in the heavier sedation arm to 20.6% in

fied observer’s assessment of alertness/sedation score [OAA/ the lighter sedation arm with 80% power using a 2-sided

S], 0-2) or lighter (OAA/S, 3–5) intraoperative sedation levels.9 test with a type I error of 0.05 through a sample of 200 par-

An OAA/S range for each sedation level was felt to more accu- ticipants in equal allocation who were randomly assigned to

rately reflect the clinical picture because exact OAA/S targets the 2 study arms.8 These power assumptions were based on

cannot always be achieved. The inclusion criteria were (1) ad- our preliminary randomized clinical trial.13

mission to Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center for surgi-

cal repair of a traumatic hip fracture, (2) being age 65 years or Statistical Analysis

older, (3) a preoperative Mini-Mental State Examination All analyses were conducted with the intention-to-treat

(MMSE) score of 15 or higher,10 and (4) receiving spinal anes- principle. The incidence of delirium in the 2 intervention

thesia. The exclusion criteria included (1) receiving general an- groups was compared using the time-to-event analytic

esthesia, (2) an inability to speak or understand English, (3) se- approach. The cumulative incidence of PD was estimated by

vere chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or congestive heart a Kaplan-Meier analysis, and the between-group difference

988 JAMA Surgery November 2018 Volume 153, Number 11 (Reprinted) jamasurgery.com

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by a Tulane University User on 01/17/2019

Effect of Depth of Sedation in Older Patients Undergoing Hip Fracture Repair on Postoperative Delirium Original Investigation Research

of incidence was compared with the log-rank test. The rela- had a smoking history, and 27 (13.5%) scored 2 or greater on

tive risk of PD between intervention groups was evaluated the CAGE16 alcoholism questionnaire.

with Cox proportional hazards models. The proportionality The baseline cognitive testing results were comparable be-

assumption was verified using Schoenfeld residuals and a tween intervention groups. A Geriatric Depression Scale score

proportionality test. The secondary outcomes included the of 6 or more occurred for 51 participants (25.5%),17 and 116

tracking of daily MMSE scores, DRS severity, and total (58%) had a Clinical Dementia Rating score of 0.5 or more.18

scores during the participant’s hospital stay using a non- The mean (SD) MMSE score for all participants was 24 (4). The

parametric regression. Between-group comparisons were type of fracture and surgical procedure, including the use of

conducted with mixed-effects linear models.8 The binary cement, did not differ between intervention groups (Table 1).

outcome of PD that occurred in both intervention groups

was evaluated by a logistic regression. All of the modeling Intervention

approaches accounted for the age and MMSE score at base- Intraoperatively, the separation between groups was good

line that was used in stratified randomization. Our only pre- (Table 2), as indicated by both modified OAA/S and EEG cri-

planned subgroup analyses explored the heterogeneity of teria (Bispectral index; BIS Brain Monitoring System,

intervention effects by stratifying the study groups accord- http://www.medtronic.com/covidien/products/brain-

ing to the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) score.14 The CCI monitoring). The sedation scores demonstrate a clinical dif-

score was not age corrected and was calculated as previ- ference between lighter (OAA/S ~ 4 represents a lethargic

ously described,14 except that baseline a Clinical Dementia response to calling a name in a normal tone) vs heavier

Rating score of 1 or more defined dementia. The treatment sedation levels (OAA/S ~ 0 occurs when the participant does

interaction with the CCI scores on the time-to-event out- not respond to noxious stimuli). The bispectral index values

come was tested with a Cox proportional hazards model and reflect the same clinical differences as the OAA/S scores. As

accounted for the covariates that were related to the out- expected, the heavier sedation group received a higher total

come and the CCI scores. Treatment-CCI interactions on the propofol dose. No intraoperative narcotics or benzodiaz-

binary outcome of PD were tested by a logistic regression epines were administered to any patient. Patients in the

similarly. In these subgroup analyses, we treated the CCI heavier sedation group had longer surgical times secondary

scores as categorical variables in exploratory analyses to to prolonged awakening. Intraoperative mean arterial pres-

identify parsimonious effect modification models. We sure was lower in the heavier sedation group secondary to

tested them as a continuous variable that extended through the cardiovascular depressant effects of propofol. The over-

the full range of CCI scores and as a “truncated” variable all level of spinal anesthesia was T9 ± 1.5 dermatomes. Most

that combined all scores of 3 or more as more than 2. Base- blood transfusions occurred postoperatively within 72

line characteristics that are associated with PD and CCI hours, with only 4 patients (2%) receiving intraoperative

scores were adjusted for in these effect modification mod- transfusions.

els, in addition to baseline age and MMSE scores. All analy-

ses were conducted with SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Patient Follow-up

Postoperative ICU admission rates, opioid consumption,

and pain scores were similar in the 2 intervention groups

(Table 2). All patients who were admitted to the ICU postop-

Results eratively had a 1-day length of stay. No patients in the ICU

Figure 1 outlines the Consolidated Standards of Reporting dia- required intubation. The postoperative length of stay and

gram for STRIDE. Of 538 patients with a hip fracture who were hospital discharge location were comparable between inter-

screened from November 18, 2011, through May 19, 2016, 200 vention groups. There was no difference between groups in

patients (37.2%) were randomized to receive either lighter or incidence or type of complications during the first 30 post-

heavier sedation levels. The most common reasons for ineli- operative days.

gibility were an age younger than 65 years (97 [18.0%]) and an

MMSE score of less than 15 (88 [16.4%]). Of 225 eligible pa- Effect of Intervention on Incident PD

tients who were approached to provide consent, only 10 (4.4%) Without adjusting for comorbidities, the incidence of a de-

declined participation; 15 (6.7%) became ineligible between the lirium diagnosis at any time during postoperative days 1 to 5

time of consent and surgery. was 39% (n = 39) in the heavier sedation group and 34% (n = 34)

in the lighter sedation group (P = .46, by χ2 analysis). The over-

Baseline Characteristics all incidence was 36.5% (n = 73). Although we observed con-

Baseline demographics were similar in the 2 intervention sistently less PD in patients who received lighter sedation lev-

groups (Table 1). Forty-eight participants (24%) had any edu- els, the difference between groups was not statistically

cation beyond high school. The baseline comorbidities, as as- significant. An intention-to-treat analysis showed no statisti-

sessed by CCI scores, and functional status were well- cal difference between groups in incident PD, total days of PD,

matched between the groups. Sixty-seven (33.5%) and 75 or total days of PD + subsyndromal symptoms (Figure 2). Sec-

(37.5%) participants were capable of performing all physical ondary outcomes showed that DRS severity was higher and

self-maintenance scale items and the instrumental activities MMSE scores were lower in the heavier sedation group on post-

of daily living items, respectively.15 One-hundred sixteen (58%) operative day 1 (eFigure in Supplement 2).

jamasurgery.com (Reprinted) JAMA Surgery November 2018 Volume 153, Number 11 989

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by a Tulane University User on 01/17/2019

Research Original Investigation Effect of Depth of Sedation in Older Patients Undergoing Hip Fracture Repair on Postoperative Delirium

Figure 1. Consolidated Standard of Reporting Diagram for STRIDE Study

538 Hip fractures repaired at JHBMC

313 Excluded

88 Failed MMSE score or dementia

97 Too young

6 Previous extensive lumbar spinal surgery

18 Delirious

64 Taking anticoagulation medications

15 Medically unstable

8 Non-English speaker

5 Multiple fractures

6 Prior hip repair

6 No research staff members available

225 Eligible to consent

10 Excluded (declined)

215 Consented

15 Excluded

3 Delirious prior to surgery

5 Taking anticoagulation medications

3 Medically unstable

2 Surgeon refused

1 No staff members available

1 Failed spinal examination

200 Randomized

100 Randomized to receive lighter 100 Randomized to receive heavier

sedation levels sedation levels

100 In-hospital outcome data 100 In-hospital outcome data

1 Return to operating room on 1 Death on postoperative day 2

postoperative day 0 1 Return to operating room on

1 Withdrew consent on postoperative day 2

postoperative day 1 1 Death on postoperative day 5 Patients were recruited between

1 Death on postoperative day 3 November 18, 2011, and May 19,

1 Return to operating room on 2016. JHBMC indicates John Hopkins

postoperative day 4

Bayview Medical Center; MMSE,

Mini-Mental State Examination.

Interaction Between Comorbidity

and Intervention in Determining Incident PD Discussion

Incorporating a model that was adjusted for covariates that

were associated with PD in the literature19,20 and this data The overall intention-to-treat analysis, without considering co-

set (age, MMSE score, fracture type, Geriatric Depression morbidity, showed no statistically significant benefits of lighter

Scale score) revealed significant interaction between seda- sedation levels during hip fracture repair under spinal anes-

tion levels and CCI in determining PD. Significant interac- thesia. However, secondary analyses that incorporated the con-

tions occurred in the time-to-event outcome in the form of sideration of comorbidities suggested that this lack of overall

hazards ratios that were associated with the intervention effect may be due to the heterogeneity of treatment effects

from the Cox regression models as well as the risk in the (HTE) that was associated with baseline comorbidity. Pre-

binar y outcome of ever receiv ing a diagnosis of PD planned secondary analyses for HTE showed that comorbidi-

(Figure 3). In patients with a baseline CCI score of 0, heavier ties may modify the treatment effect of sedation levels on PD

sedation levels doubled the risk of PD (hazard ratio, 2.3; risk in this older population with hip fracture. Lighter seda-

95% CI, 1.1–4.9). In patients with higher baseline comorbid- tion levels were associated with lower PD incidence, but the

ity, as indicated by a CCI score of more than 0, the level of difference from the heavier sedation group was statistically sig-

sedation was not related to incident PD (eTables 1-4 in nificant only in the subgroup with less comorbidity. At higher

Supplement 2). levels of comorbidity, the benefit of lowering PD risk by lighter

990 JAMA Surgery November 2018 Volume 153, Number 11 (Reprinted) jamasurgery.com

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by a Tulane University User on 01/17/2019

Effect of Depth of Sedation in Older Patients Undergoing Hip Fracture Repair on Postoperative Delirium Original Investigation Research

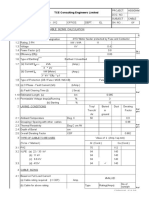

Table 1. Baseline Patient Characteristics by Depth of Sedation During Surgery

No. (%)

Total Lighter Heavier

Characteristic (N = 200) (n = 100) (n = 100)

Age, mean (SD), y 81.8 (7.7) 81.6 (8.2) 82.0 (7.2)

Body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by 25.0 (5.3) 25.2 (5.2) 24.8 (5.4)

height in meters squared), mean (SD)

Female 146 (73.0) 72 (72.0) 74 (74.0)

White race/ethnicity 194 (97.0) 97 (97.0) 97 (97.0)

Education level

Less than high school 76 (38.0) 37 (37.0) 39 (39.0)

High school 76 (38.0) 37 (37.0) 39 (39.0)

Some college 28 (14.0) 16 (16.0) 12 (12.0)

College graduate or higher 20 (10.0) 10 (10.0) 10 (10.0)

Employment

Retired/disabled 162 (81.0) 83 (83.0) 79 (79.0)

Working full-time/part-time 7 (3.5) 3 (3.0) 4 (2.0)

Homemaker 31 (15.5) 14 (14.0) 17 (17.0)

Residence

Own home/family home 172 (86.0) 82 (82.0) 90 (90.0)

Assisted living/nursing home 7 (3.5) 6 (6.0) 1 (1.0)

Other 21 (10.5) 12 (12.0) 9 (9.0)

Reside with

Alone 85 (42.5) 44 (44.0) 41 (41.0)

Spouse/partner 47 (28.0) 21 (27.0) 26 (29.0)

Family member (nonspouse) 52 (30.5) 23 (29.0) 29 (32.0)

Nonfamily member 1 (0.5) 0 1 (1.0)

Other 15 (3.0) 12 (6.0) 3 (0.0)

Status prior to surgery

Charlson comorbidity index score, mean (SD) 1.5 (1.8) 1.5 (1.8) 1.6 (1.8)

American Society of Anesthesiologist rating ≥3 139 (69.5) 63 (63.0) 76 (76.0)

PSMS, mean (SD) 4.61 (1.52) 4.66 (1.48) 4.56 (1.57)

IADL scale, mean (SD) 5.85 (2.22) 5.84 (2.17) 5.86 (2.28)

Alcohol, CAGE score ≥2 27 (13.5) 7 (7.0) 20 (20.0)

Current cigarette smoker 31 (15.5) 18 (18.0) 13 (13.0)

Baseline cognitive testing

Mini-Mental State Examination score, mean (SD) 24.3 (3.7) 24.4 (3.8) 24.2 (3.6)

Geriatric Depression score, mean (SD) 3.83 (3.48) 3.86 (3.71) 3.80 (3.25)

Clinical Dementia Rating score (n = 198/99/99)

0 82 (41.4) 46 (46.5) 36 (36.4)

0.5 94 (47.5) 43 (43.4) 51 (51.5)

1 16 (8.1) 7 (7.1) 9 (9.1)

2 6 (3.0) 3 (3.0) 3 (3.0)

Subsyndromal delirium 13 (6.5) 4 (4.0) 9 (9.0)

Surgery characteristics

Emergency department to surgery, mean (SD), d 1.2 (1.0) 1.3 (1.2) 1.2 (0.6)

Type of fracture

Femoral neck 89 (44.5) 42 (42.0) 47 (47.0)

Inter/subtrochanteric 111 (55.5) 58 (58.0) 53 (53.0)

Type of procedure

Hemiarthroplasty with/without cement 69 (34.5) 31 (31.0) 38 (38.0)

Total hip arthroplasty with/without cement 11 (5.5) 5 (5.0) 6 (6.0)

Cannulated screw 9 (4.5) 7 (7.0) 2 (2.0) Abbreviations: CAGE, cut annoyed

Intramedullary nail 110 (55.0) 57 (57.0) 53 (53.0) guilty eye; IADL, instrumental

activities of daily living; PSMS,

Girdlestone 1 (0.5) 0 (0.0) 1 (1.0)

physical self-maintenance scale.

jamasurgery.com (Reprinted) JAMA Surgery November 2018 Volume 153, Number 11 991

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by a Tulane University User on 01/17/2019

Research Original Investigation Effect of Depth of Sedation in Older Patients Undergoing Hip Fracture Repair on Postoperative Delirium

Table 2. Intraoperative and Postoperative Data by Depth of Sedation During Surgery

Mean (SD)

Lighter Heavier

Characteristic (n = 100) (n = 100) P Value

Intraoperative

Modified Observer’s Assessment of Alertness/Sedation scale from incision 4.1 (0.9) 0.2 (0.4) <.001

to the end of surgerya

Proportion of Modified Observer’s Assessment of Alertness/Sedation Scale 89.9 97.7

recordings that fall in the desired range (0-2 for heavier levels and 3-5 for

lighter sedation levels) from incision to the end of surgery, %

Bispectral Index (n = 197/98/99) from incision to the end of surgeryb 82.3 (9.4) 57.0 (14.8) <.001

Total propofol dose, mg 314.8 (185.0) 739.1 (342.8) <.001

Total propofol dose by body weight, mg/kg 4.6 (2.3) 11.1 (4.4) <.001

Incision to end of surgery, min 86.3 (31.0) 96.8 (36.9) .03

Mean arterial pressure, mm Hg, (n = 199/99/100) from incision to the end 75.7 (11.2) 71.9 (9.5) .01

of surgery

Estimated blood loss 183.5 (154.5) 201.3 (146.9) .41

Participants receiving an intraoperative RBC transfusion, No. (%) 1 (1.0) 3 (3.0) .62

Participants receiving a blood transfusion, within 72 h postoperative, 37 (39.0) 38 (39.2) .99

No. (%)c

Postoperative

Mean daily morphine equivalents by weight, mg/kg 0.13 (0.13) 0.16 (0.19) .14

Mean daily pain score (Likert, 0-10) 3.4 (2.6) 3.9 (2.4) .20 Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care

Postoperative admission to ICU, No. (%) 11 (11.0) 13 (13.0) .74 unit; RBC, red blood cells.

a

Surgery until discharge, d 4.1 (2.6) 3.7 (2.5) .27 Sedation scores range from 0

(unresponsive) to 5 (wide awake).

Discharge location, No. (%) b

Bispectral index values range from

Rehabilitation center 85 (85.0) 89 (89.0) 40 to 60 (general anesthesia) to

Nursing home/assisted living 1 (1.0) 0 100 (wide awake).

.72 c

Own home/family home 11 (11.0) 9 (9.0) Of 192, there were 95 (49.5%) in the

lighter sedation arm and 97 (50.5%)

Other/death 3 (3.0) 2 (2.0)

in the heavier sedation arm.

electroencephalography criteria (bispectral index) to deter-

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Curve Showing Intention-to-Treat Analysis

mine lighter or heavier sedation levels. In that study, lighter

of Cumulative Incidence of Delirium During Postoperative Days 1 to 5

in the Lighter Sedation and Heavier Sedation Groups sedation levels decreased the prevalence of PD by 50% com-

pared with heavier sedation levels. However, the bispectral in-

0.5 dex is not routinely used to manage sedation because of its poor

correlation with sedation scores, particularly in ICU patients.21

Cumulative Incidence of Delirium

Heavier sedation levels

0.4

Additionally, several patients received multiple sedative agents,

Lighter sedation levels making the assessment of propofol-specific effects difficult.

0.3

Furthermore, the total propofol dose was greater in the lighter

sedation intervention arm of STRIDE than in the lighter seda-

0.2

tion intervention arm of the previous study (4.6 ± 2.3 vs

0.1

2.5 ± 2.7 mg/kg, respectively). Our propofol doses were higher,

having administered additional propofol to perform spinal an-

0 esthesia rather than other sedative agents to avoid any con-

Surgery 1 2 3 4 5 founding effects. Although the exact propofol dosage that is

Postoperative Time, d

required to transition to delirium is unclear,4 in vulnerable

No. at risk

Sedation levels

populations, propofol can precipitate delirium. Used as a seda-

Heavier 0/100 28/100 9/70 1/44 0/20 1/9 tive in the ICU, propofol is associated with rapidly reversible

Lighter 0/100 25/99 6/71 2/51 1/30 0/17

and persistent delirium.22 Furthermore, hallucinations and de-

Log-rank P = .46.

lirium are reported after patients receive propofol doses simi-

lar to those administered in the STRIDE lighter sedation treat-

ment arm.23,24

sedation levels was attenuated. The selection of a sedation level The trial was not sufficiently powered to detect any inter-

can be an important decision in many patients as a means of vention effect that would allow a greater than 20.6% PD risk

decreasing PD. However, the benefits of lighter sedation lev- in the lighter sedation arm. The small overall PD reduction that

els may be overridden by baseline comorbidities. was observed with lighter sedation levels is far from the level

The contribution of sedation depth to PD risk was exam- that was hypothesized in the power calculation. However, the

ined in a previous randomized double-blind trial13 that used hypothesized study power is not totally unfounded, as the larg-

992 JAMA Surgery November 2018 Volume 153, Number 11 (Reprinted) jamasurgery.com

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by a Tulane University User on 01/17/2019

Effect of Depth of Sedation in Older Patients Undergoing Hip Fracture Repair on Postoperative Delirium Original Investigation Research

Figure 3. Charlson Comorbidity Index Scores

A Heavier vs lighter sedation levels B Risk estimates C Charlson comorbidity index score

adjusted hazard ratio

3.5 0.7 40

Risk of Postoperative Delirium in Hospital

Heavier sedation levels

3.0 0.6 Lighter sedation levels

30

Adjusted Hazard Ratio

2.5 0.5

Patients, %

2.0 0.4

20

1.5 0.3

1.0 0.2

10

0.5 0.1

0 0 0

0 1 2 ≥2 0 1 2 ≥2 0 1 2 ≥2

Charlson Comorbidity Index Score Charlson Comorbidity Index Score Charlson Comorbidity Index Score

A, The adjusted hazard ratio showed that patients with the least comorbidity (Charlson comorbidity index = 0) were 2.3 times more likely to experience

postoperative delirium after receiving heavier sedation levels than after receiving lighter sedation levels. B, Risk estimates for in-hospital postoperative delirium by

treatment group and the associated 95% confidence intervals. Sample sizes (incident cases/total cases) are indicated in eTable 1 in Supplement 2. B, The difference

in delirium risk after heavier and lighter sedation levels was not significant in patients with greater preoperative comorbidity. The dashed horizontal line indicates a

36.5% risk of in-hospital postoperative delirium, which was the estimated overall risk from the entire STRIDE sample. C, Percentage of patients stratified by Charlson

comorbidity index score.

est CCI subgroup, a CCI score of 0, exhibited effects from se- study strengths include using propofol as the only interven-

dation depth that were similar to those in previous studies.13 tional drug. The high consent rate reduced selection bias. Com-

The CCI score when treated as a continuous score modifies se- pared with previous work, the methods were more rigorous.

dation depth effects on PD after adjusting for PD risk factors. Four anesthesiologists anesthetized and managed all STRIDE

At a CCI score of 0, lighter sedation levels were protective. The cases in a consistent manner, and there were no protocol vio-

observation that higher CCI scores decreased the ability to pre- lations or group crossovers. Although a single-center study can

vent PD by modifying the depth of sedation is consistent with lead to a loss of generalizability, we believe that protocol con-

other studies that demonstrated that baseline vulnerabilities sistency and treated assignment administration outweighed this

are the important independent drivers behind the develop- weakness. Additionally, hip fracture demographics are charac-

ment of PD.25 We previously reported that dementia is a strong terized by an older white female population.27 The STRIDE

risk factor for PD in patients with hip fractures.26 The high population reflects these demographics and its PD prevalence

prevalence of baseline cognitive dysfunction in the STRIDE par- is consistent with recent multicenter trials.28-30 The periopera-

ticipants may have also influenced PD incidence, particularly tive delirium assessment was done in a systematic manner using

at higher CCI scores. In addition, at a higher CCI, the estimate standardized tools and a consensus panel. The randomization

suggests a reverse situation in that heavier sedation levels produced an excellent matching of participants in the 2 inter-

might be protective. However, the trend was not significant vention groups. There were well-defined intraoperative differ-

and the estimate was unstable owing to small patient num- ences in sedation levels between the intervention groups in

bers at a high CCI. These factors limit our ability to investi- terms of the propofol dose, OAAS, and bispectral index. Fur-

gate the reason for this reversal of effects and warrant addi- thermore, bias was minimized in the delirium assessments and

tional studies. Several hypothesis that generate analysis were diagnostic process via a masking of assessors and consensus

performed to elucidate the potential mechanisms that influ- panel members to group assignments. The sample size was ad-

enced the CCI interaction and intervention effect. The demen- equate to detect significant clinical effects.

tia CCI item alone did not predict PD after adjusting for base- One study weakness was the limiting of delirium testing to

line risk factors. When the CCI cardiovascular items were the first 5 postoperative days or until hospital discharge. Fol-

combined as a single score, there was significant interven- lowing hip fracture repair, the highest incidence of PD occurs

tion effect modification by this combined vascular score and on postoperative day 1,30,31 as confirmed in Figure 2. Further-

risk of PD (χ2 = 4.07; P = .04), suggesting a cardiovascular more, delirium duration in STRIDE was comparable with other

mechanism. studies that examined longer follow-up periods.32 Although

some observations were cut short because of death, return to

Strengths and Limitations the operating room, or withdrawal, observations are available

STRIDE is an efficacy trial that examined whether lighter seda- on every participant. Because most PD cases occurred on days

tion levels produces clinically meaningful effects in reducing 1 and 2 and the time-to-event approach treats the small num-

PD incidence in a high-risk population. To best answer this ques- bers of observations that were cut short as censoring, the po-

tion, we controlled as many variables as possible. The STRIDE tential effect on our results would be minimal. Therefore, al-

jamasurgery.com (Reprinted) JAMA Surgery November 2018 Volume 153, Number 11 993

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by a Tulane University User on 01/17/2019

Research Original Investigation Effect of Depth of Sedation in Older Patients Undergoing Hip Fracture Repair on Postoperative Delirium

though statistical inaccuracy due to a shorter follow-up in geneity is the expected clinical norm, and when assessing for

STRIDE cannot be completely ruled out, the likelihood of inac- the interaction with comorbidity, we did find significant treat-

curacy is small. We did not measure delirium subtypes, which ment effects in the low-comorbidity subgroup. Besides in-

could represent an unintended consequence of the interven- hospital PD outcomes, it is important to determine the inter-

tion. Only patients who could safely undergo spinal anesthe- vention effects on long-term functional and cognitive outcomes.

sia were included. Although the study results cannot necessar- These data are in the process of analysis and will be reported in

ily be generalized to all hip fracture patients, in the United States a separate article.

approximately 40% of all hip fracture repairs are performed with

spinal anesthesia.26 The study results may not hold with anes-

thetic agents other than propofol. However, propofol is the most

widely used drug for sedation. The STRIDE participants could

Conclusions

reflect a healthier study population. However, the mean STRIDE In a subgroup analysis, the STRIDE results suggest that PD

CCI score33 and distribution of CCI scores were consistent with can be reduced in individuals with a CCI score of 0 by

the literature.34 Several comorbidities that were included in the reducing sedation levels. The STRIDE trial suggests that the

CCI calculation are associated with underlying cognitive selection of sedation levels can be an important means of

dysfunction,35-37 but our multivariant analysis controlled for decreasing PD in many patients. However, the associated

baseline MMSE scores. Because CCI is not a complete surro- benefits of lighter sedation levels may be obscured by com-

gate measure for baseline risk factors of delirium, the model- peting baseline comorbidities, placing patients at risk of

ing results may have been limited. A prespecified subgroup developing PD. Given the STRIDE trial findings, the chal-

analysis to look for HTE must be interpreted carefully. Hetero- lenge for future research will be to determine the mecha-

geneity and comorbidity in this population may have limited nisms and interactional relationships between comorbidi-

our ability to detect significant overall effects. However, hetero- ties and precipitating risk factors for PD.

ARTICLE INFORMATION responsibility for the integrity of the data and the To gain access, data requestors will need to sign a

Accepted for Publication: May 13, 2018. accuracy of the data analysis. data access agreement.

Concept and design: Sieber, Neufeld, Gottschalk, Additional Contributions: We thank the

Published Online: August 8, 2018. Rosenberg, Mears, Stewart, Li, Wang.

doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2602 assessment team (Kori Kindbom, MA, Rachel Burns,

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: BS, and Michael Sklar, MA, Johns Hopkins

Author Affiliations: Department of Anesthesiology Sieber, Neufeld, Gottschalk, Bigelow, Oh, University School of Medicine) for their follow-up of

and Critical Care Medicine, Johns Hopkins Bayview Rosenberg, Mears, Stewart, Ouanes, Jaberi, patients. These individuals were part of the study

Medical Center, Baltimore, Maryland (Sieber, Hasenboehler, Wang. assessment and follow-up team and were

Jaberi); Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Drafting of the manuscript: Sieber, Gottschalk, compensated for their services through the study’s

Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Bigelow, Oh, Rosenberg, Wang. National Institutes of Health grant. We also thank

Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland (Neufeld, Critical revision of the manuscript for important the data safety and monitoring board members

Rosenberg); Department of Anesthesiology and intellectual content: All authors. (Jeffery Carson, MD, Rutgers University, Lee

Critical Care Medicine, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Statistical analysis: Sieber, Wang. Fleisher, MD, University of Pennsylvania, Steve

Baltimore, Maryland (Gottschalk, Ouanes); Obtained funding: Sieber, Gottschalk, Wang. Epstein, MD, Georgetown University, Jay

Department of Neurosurgery, Johns Hopkins Administrative, technical, or material support: Magaziner, PhD, University of Maryland, Anne

Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland (Gottschalk); Sieber, Neufeld, Gottschalk, Bigelow, Oh, Mears, Lindblad, PhD, the Emmes Corporation, and Sarang

Behavioral Pharmacology Research Unit, Johns Stewart, Ouanes. Kim, MD, Rutgers University) for their time, effort,

Hopkins University School of Medicine, J. V. Brady Supervision: Sieber, Neufeld, Bigelow. and oversight (see protocol) and Linda Sevier,

Behavioral Biology Research Center, Johns Hopkins Other - classification interpretation of all included Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, for her

Bayview Campus, Baltimore, Maryland (Bigelow); hip fractures: Hasenboehler. preparation of the manuscript.

Division of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology, Other - data management: Stewart.

Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences & Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported. REFERENCES

Neuropathology, Johns Hopkins University School

of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland (Oh); Department Funding/Support: This research was supported by 1. Gleason LJ, Schmitt EM, Kosar CM, et al. Effect of

of Orthopedic Surgery, University of Arkansas for National Institute on Aging grant R01 AG033615. delirium and other major complications on

Medical Sciences. Little Rock (Mears); Johns Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The National outcomes after elective surgery in older adults.

Hopkins University School of Medicine, Johns Institute of Aging had no role in the design and JAMA Surg. 2015;150(12):1134-1140. doi:10.1001

Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, conduct of the study; collection, management, /jamasurg.2015.2606

Maryland (Stewart); Adult and Trauma Surgery, analysis, and interpretation of the data; 2. Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y,

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Johns preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; Leo-Summers L, Inouye SK. One-year health care

Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, and decision to submit the manuscript for costs associated with delirium in the elderly

Maryland (Hasenboehler); Center for Clinical Trials publication. population. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):27-32.

and Evidence Synthesis, Department of Reducible Research Statement: Individual doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2007.4

Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of participant data that underlie the results reported 3. Pandharipande P, Ely EW. Sedative and analgesic

Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland (Li); in this article, study protocol, statistical analysis medications: risk factors for delirium and sleep

Departments of Medicine (General Internal plan, and analytic code will be available for analysis disturbances in the critically ill. Crit Care Clin.

Medicine), Biostatistics, and Epidemiology, and after deidentification (text, tables, figures, and 2006;22(2):313-327, vii. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2006.02

Welch Center for Prevention, Epidemiology, and appendices) beginning 9 months and ending 36 .010

Clinical Research, The Johns Hopkins University, months after article publication to researchers who

Baltimore, Maryland (Wang). 4. Pandharipande P, Shintani A, Peterson J, et al.

provide a methodologically sound proposal to Lorazepam is an independent risk factor for

Author Contributions: Drs Sieber and Wang had achieve the aims in the approved proposal. transitioning to delirium in intensive care unit

full access to all the data in the study and take Proposals should be directed to fsieber1@jhmi.edu. patients. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(1):21-26.

doi:10.1097/00000542-200601000-00005

994 JAMA Surgery November 2018 Volume 153, Number 11 (Reprinted) jamasurgery.com

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by a Tulane University User on 01/17/2019

Effect of Depth of Sedation in Older Patients Undergoing Hip Fracture Repair on Postoperative Delirium Original Investigation Research

5. Dubois MJ, Bergeron N, Dumont M, Dial S, 16. Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE with hip fracture: a multicentre, double-blind

Skrobik Y. Delirium in an intensive care unit: a study questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252(14):1905-1907. randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2014;186(14):

of risk factors. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(8): doi:10.1001/jama.1984.03350140051025 E547-E556. doi:10.1503/cmaj.140495

1297-1304. doi:10.1007/s001340101017 17. Yesavage JA, Sheikh JI. 9/Geriatric Depression 29. Carson JL, Terrin ML, Noveck H, et al; FOCUS

6. Marcantonio ER, Goldman L, Mangione CM, Scale (GDS). Clin Gerontol. 1986;5(1-2):165-173. Investigators. Liberal or restrictive transfusion in

et al. A clinical prediction rule for delirium after doi:10.1300/J018v05n01_09 high-risk patients after hip surgery. N Engl J Med.

elective noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 1994;271(2): 18. Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): 2011;365(26):2453-2462. doi:10.1056

134-139. doi:10.1001/jama.1994.03510260066030 current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993; /NEJMoa1012452

7. Sieber FE, Gottshalk A, Zakriya KJ, Mears SC, Lee 43(11):2412-2414. doi:10.1212/WNL.43.11.2412-a 30. Gruber-Baldini AL, Marcantonio E, Orwig D,

H. General anesthesia occurs frequently in elderly 19. Smith PJ, Attix DK, Weldon BC, Monk TG. et al. Delirium outcomes in a randomized trial of

patients during propofol-based sedation and spinal Depressive symptoms and risk of postoperative blood transfusion thresholds in hospitalized older

anesthesia. J Clin Anesth. 2010;22(3):179-183. delirium. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24(3): adults with hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61

doi:10.1016/j.jclinane.2009.06.005 232-238. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2015.12.004 (8):1286-1295. doi:10.1111/jgs.12396

8. Li T, Wieland LS, Oh E, et al. Design 20. Gruber-Baldini AL, Zimmerman S, Morrison RS, 31. Duppils GS, Wikblad K. Acute confusional states

considerations of a randomized controlled trial of et al. Cognitive impairment in hip fracture patients: in patients undergoing hip surgery. a prospective

sedation level during hip fracture repair surgery: timing of detection and longitudinal follow-up. J Am observation study. Gerontology. 2000;46(1):36-43.

a strategy to reduce the incidence of postoperative Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(9):1227-1236. doi:10.1046/j doi:10.1159/000022131

delirium in elderly patients. Clin Trials. 2017;14(3): .1532-5415.2003.51406.x 32. Bellelli G, Mazzola P, Morandi A, et al. Duration

299-307. doi:10.1177/1740774516687253 of postoperative delirium is an independent

21. Hajat Z, Ahmad N, Andrzejowski J. The role and

9. Glass PS, Bloom M, Kearse L, Rosow C, Sebel P, limitations of EEG-based depth of anaesthesia predictor of 6-month mortality in older adults after

Manberg P. Bispectral analysis measures sedation monitoring in theatres and intensive care. hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(7):1335-1340.

and memory effects of propofol, midazolam, Anaesthesia. 2017;72(suppl 1):38-47. doi:10.1111/anae doi:10.1111/jgs.12885

isoflurane, and alfentanil in healthy volunteers. .13739 33. Burgos E, Gómez-Arnau JI, Díez R, Muñoz L,

Anesthesiology. 1997;86(4):836-847. doi:10.1097 Fernández-Guisasola J, Garcia del Valle S. Predictive

/00000542-199704000-00014 22. Patel SB, Poston JT, Pohlman A, Hall JB, Kress

JP. Rapidly reversible, sedation-related delirium value of six risk scores for outcome after surgical

10. Folstein MFFS, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. versus persistent delirium in the intensive care unit. repair of hip fracture in elderly patients. Acta

“Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(6):658-665. Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52(1):125-131. doi:10.1111/j

the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. doi:10.1164/rccm.201310-1815OC .1399-6576.2007.01473.x

J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. doi:10.1016 34. Johnson DJ, Greenberg SE, Sathiyakumar V,

/0022-3956(75)90026-6 23. Brown KE, Mirrakhimov AE, Yeddula K, Kwatra

MM. Propofol and the risk of delirium: exploring the et al. Relationship between the Charlson

11. Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, anticholinergic properties of propofol. Med Comorbidity Index and cost of treating hip

Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the Hypotheses. 2013;81(4):536-539. doi:10.1016/j.mehy fractures: implications for bundled payment.

confusion assessment method. A new method for .2013.06.027 J Orthop Traumatol. 2015;16(3):209-213. doi:10

detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12): .1007/s10195-015-0337-z

941-948. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941 24. Balasubramaniam B, Park GR. Sexual

hallucinations during and after sedation and 35. Yohannes AM, Chen W, Moga AM, Leroi I,

12. Trzepacz PT, Mittal D, Torres R, Kanary K, anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2003;58(6):549-553. Connolly MJ. Cognitive impairment in chronic

Norton J, Jimerson N. Validation of the delirium doi:10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.03147.x obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic heart

rating scale-revised-98: comparison with the failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of

delirium rating scale and the cognitive test for 25. Inouye SK, Zhang Y, Jones RN, Kiely DK, Yang F, observational studies. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18

delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;13 Marcantonio ER. Risk factors for delirium at (5):451.e1-451.e11. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2017.01.014

(2):229-242. doi:10.1176/jnp.13.2.229 discharge: development and validation of a

predictive model. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(13): 36. Yaffe K, Ackerson L, Kurella Tamura M, et al;

13. Sieber FE, Zakriya KJ, Gottschalk A, et al. 1406-1413. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.13.1406 Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Investigators.

Sedation depth during spinal anesthesia and the Chronic kidney disease and cognitive function in

development of postoperative delirium in elderly 26. Lee HB, Mears SC, Rosenberg PB, Leoutsakos older adults: findings from the chronic renal

patients undergoing hip fracture repair. Mayo Clin JM, Gottschalk A, Sieber FE. Predisposing factors insufficiency cohort cognitive study. J Am Geriatr Soc.

Proc. 2010;85(1):18-26. doi:10.4065/mcp.2009 for postoperative delirium after hip fracture repair 2010;58(2):338-345. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009

.0469 in individuals with and without dementia. J Am .02670.x

Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(12):2306-2313. doi:10.1111/j

14. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. .1532-5415.2011.03725.x 37. Eggermont LH, de Boer K, Muller M, Jaschke

A new method of classifying prognostic AC, Kamp O, Scherder EJ. Cardiac disease and

comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development 27. Friedman SM, Mendelson DA. Epidemiology of cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Heart.

and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. fragility fractures. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014;30(2):175- 2012;98(18):1334-1340. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2012

doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 181. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2014.01.001 -301682

15. Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older 28. de Jonghe A, van Munster BC, Goslings JC,

people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities et al; Amsterdam Delirium Study Group. Effect of

of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179-186. melatonin on incidence of delirium among patients

doi:10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179

jamasurgery.com (Reprinted) JAMA Surgery November 2018 Volume 153, Number 11 995

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by a Tulane University User on 01/17/2019

You might also like

- Práctica 18 - Delirium in Older Patients After Anesthesia (Artículo para La Discusión)Document15 pagesPráctica 18 - Delirium in Older Patients After Anesthesia (Artículo para La Discusión)HENRY MAYKOL PAZ INOCENTENo ratings yet

- Jamasurgery Austin 2019 Oi 180087Document7 pagesJamasurgery Austin 2019 Oi 180087GustavoCalderinNo ratings yet

- Jamasurgery Dehghan 2022 Oi 220065 1667884241.44976Document8 pagesJamasurgery Dehghan 2022 Oi 220065 1667884241.44976Gabriel FernandesNo ratings yet

- Grosse-Sundrup2012 Score PredictifDocument2 pagesGrosse-Sundrup2012 Score PredictifZinar PehlivanNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors of Preoperative Anaesthesia EvaluationDocument2 pagesRisk Factors of Preoperative Anaesthesia EvaluationNur intan cahyaniNo ratings yet

- Regional Techniques For Cardiac and Cardiac-Related ProceduresDocument15 pagesRegional Techniques For Cardiac and Cardiac-Related Procedures凌晓敏No ratings yet

- HANDOVER EN ANESTESIA-jama - Meersch - 2022 - Oi - 220060 - 1654291081.6921 (2382)Document10 pagesHANDOVER EN ANESTESIA-jama - Meersch - 2022 - Oi - 220060 - 1654291081.6921 (2382)Servando FabeloNo ratings yet

- Abstracts of The 2018 AANS/CNS Joint Section On Disorders of The Spine and Peripheral Nerves Annual MeetingDocument109 pagesAbstracts of The 2018 AANS/CNS Joint Section On Disorders of The Spine and Peripheral Nerves Annual MeetingEka Wahyu HerdiyantiNo ratings yet

- PR 2021 Cureus 13-1-E12870 1-9Document9 pagesPR 2021 Cureus 13-1-E12870 1-9aditya galih wicaksonoNo ratings yet

- Broadbent 2012Document6 pagesBroadbent 2012Czakó KrisztinaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Reading M.rafi FarnoDocument12 pagesJurnal Reading M.rafi FarnoFhy Ghokiel AbiezNo ratings yet

- PIIS0007091219306270Document3 pagesPIIS0007091219306270irvan rahmanNo ratings yet

- BJAEd - Analgesia For Caesarean SectionDocument7 pagesBJAEd - Analgesia For Caesarean SectionDragos IonixNo ratings yet

- Neu 2021 0177Document9 pagesNeu 2021 0177divinechp07No ratings yet

- Science, Medicine, and The Anesthesiologist: Key Papers From The Most Recent Literature Relevant To AnesthesiologistsDocument4 pagesScience, Medicine, and The Anesthesiologist: Key Papers From The Most Recent Literature Relevant To AnesthesiologistsRicardoNo ratings yet

- Jamasurgery Loggers 2022 Oi 220001 1652211206.30448Document11 pagesJamasurgery Loggers 2022 Oi 220001 1652211206.30448Yeimer OrtizNo ratings yet

- MAP During CPBDocument8 pagesMAP During CPBAdy WarsanaNo ratings yet

- AnnIMedUpdate in Palliative Med Jan2008Document7 pagesAnnIMedUpdate in Palliative Med Jan2008vabcunhaNo ratings yet

- Jama Vacas 2021 It 210019 1630095346.97965Document2 pagesJama Vacas 2021 It 210019 1630095346.97965Juan Carlos Perez ParadaNo ratings yet

- Ashar 2022Document11 pagesAshar 2022RashidkpvldNo ratings yet

- Articulo IncenDocument10 pagesArticulo IncenLAURA CAMILA AVELLA GAMBANo ratings yet

- The Influence of Timing of Surgical Decompression For Acute Spinal Cord Injury - A Pooled Analysis of Individual Patient DataDocument10 pagesThe Influence of Timing of Surgical Decompression For Acute Spinal Cord Injury - A Pooled Analysis of Individual Patient DataballroomchinaNo ratings yet

- Dexamethasone For Prevention of Postoperative Shivering: A Randomized Double Blind Comparison With PethidineDocument7 pagesDexamethasone For Prevention of Postoperative Shivering: A Randomized Double Blind Comparison With PethidineWilliam OmarNo ratings yet

- Nihms-1579274 PDFDocument23 pagesNihms-1579274 PDFAhmed ElshewiNo ratings yet

- Comparing Erector Spinae Plane Block With Serratus Anterio - 2020 - British JourDocument9 pagesComparing Erector Spinae Plane Block With Serratus Anterio - 2020 - British JourtasyadelizaNo ratings yet

- Pan 13575Document2 pagesPan 13575Reynaldi HadiwijayaNo ratings yet

- Efficacy and Safety of Corticosteroid Therapy in Pati - 2024 - The American JourDocument8 pagesEfficacy and Safety of Corticosteroid Therapy in Pati - 2024 - The American JourFelipe RivasNo ratings yet

- Effect of Ultrasound Image-Guided Nerve BlockDocument9 pagesEffect of Ultrasound Image-Guided Nerve BlockMarce SiuNo ratings yet

- Air Medical Journal: David J. Dries, MSE, MDDocument4 pagesAir Medical Journal: David J. Dries, MSE, MDKat E. KimNo ratings yet

- Pain Management in Critically Ill PatientsDocument6 pagesPain Management in Critically Ill PatientsjyothiNo ratings yet

- Ketamine Vs Haloperidol For Prevention of CognitivDocument8 pagesKetamine Vs Haloperidol For Prevention of CognitivSilvia MoraNo ratings yet

- Sedation, Delirium, and Cognitive Function After Criticall IlnessDocument14 pagesSedation, Delirium, and Cognitive Function After Criticall IlnessPsiquiatría CESAMENo ratings yet

- Profilaxia de TEV em NCDocument9 pagesProfilaxia de TEV em NCSarah BernardesNo ratings yet

- Intrathecal Ziconotide in The Treatment of Refractory Pain in Patients With Cancer or AIDSDocument8 pagesIntrathecal Ziconotide in The Treatment of Refractory Pain in Patients With Cancer or AIDSSérgio TavaresNo ratings yet

- Effect Observation of Electro Acupunctute AnesthesiaDocument7 pagesEffect Observation of Electro Acupunctute Anesthesiaadink mochammadNo ratings yet

- Auditory StimulationDocument4 pagesAuditory Stimulationya latif bismillahNo ratings yet

- Managing The Agitated Patient in The ICU Sedation, Analgesia, and Neuromuscular Blockade - Honiden2010Document18 pagesManaging The Agitated Patient in The ICU Sedation, Analgesia, and Neuromuscular Blockade - Honiden2010RodrigoSachiFreitasNo ratings yet

- PAIN MangementDocument7 pagesPAIN MangementISMI NUR AINI LATIFAHNo ratings yet

- Strategies of Decresing Anxiety in The Perioperative SettingsDocument16 pagesStrategies of Decresing Anxiety in The Perioperative SettingsFiorel Loves EveryoneNo ratings yet

- Patient Education and Counseling: Lígia Pereira, Margarida Figueiredo-Braga, Irene P. CarvalhoDocument6 pagesPatient Education and Counseling: Lígia Pereira, Margarida Figueiredo-Braga, Irene P. CarvalhoAr RoshyiidNo ratings yet

- Cervical Facet PainDocument11 pagesCervical Facet PainthiagoNo ratings yet

- Scott 2014Document12 pagesScott 2014Atif MehmoodNo ratings yet

- Nihms 193974Document14 pagesNihms 193974yslin mrgthNo ratings yet

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocument11 pagesNew England Journal Medicine: The ofnaufal12345No ratings yet

- Pengaruh Kecemasan Terhadap PembedahanDocument6 pagesPengaruh Kecemasan Terhadap PembedahanRahmi Mutia UlfaNo ratings yet

- Injuryprev 2016 042156.792Document1 pageInjuryprev 2016 042156.792khadesakshi55No ratings yet

- Hoja AnestesiaDocument9 pagesHoja AnestesiaCAMILO ANDRES MANTILLANo ratings yet

- Jurnal Tumor OtakDocument6 pagesJurnal Tumor OtakJaehyun JungNo ratings yet

- JR Ibm YuanaDocument7 pagesJR Ibm Yuanayuana dnsNo ratings yet

- Sarlanietal JOrofac Pain 2004Document16 pagesSarlanietal JOrofac Pain 2004soylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Falls Sustained During Inpatient Rehabilitation After Lower Limb Amputation Prevalence and PredictorsDocument12 pagesFalls Sustained During Inpatient Rehabilitation After Lower Limb Amputation Prevalence and PredictorsFaeyz OrabiNo ratings yet

- Bismillah PDFDocument8 pagesBismillah PDFNONINo ratings yet

- FRacture ContentDocument5 pagesFRacture ContentPriya ANo ratings yet

- Httpswatermark Silverchair Com - Ezproxy.unbosque - edu.Copedsinreview.2022005642.Pdftoken AQECAHi208BE49Ooan9kkhW Ercy7Dm3ZL 9Document10 pagesHttpswatermark Silverchair Com - Ezproxy.unbosque - edu.Copedsinreview.2022005642.Pdftoken AQECAHi208BE49Ooan9kkhW Ercy7Dm3ZL 9darlingcarvajalduqueNo ratings yet

- Pain Management After Surgical Tonsillectomy: Is There A Favorable Analgesic?Document6 pagesPain Management After Surgical Tonsillectomy: Is There A Favorable Analgesic?Vladimir PutinNo ratings yet

- FX de CaderaDocument11 pagesFX de CaderaJuan Carlos Perez ParadaNo ratings yet

- Anxiety in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary InterventionsDocument8 pagesAnxiety in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary InterventionsMarina UlfaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Clinical AnesthesiaDocument2 pagesJournal of Clinical AnesthesiatsalasaNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Surgery: V. Gomathi Shankar, K. Srinivasan, Sarath C. Sistla, S. JagdishDocument4 pagesInternational Journal of Surgery: V. Gomathi Shankar, K. Srinivasan, Sarath C. Sistla, S. JagdishUswatun HasanahNo ratings yet

- Minimally Invasive Surgery for Chronic Pain Management: An Evidence-Based ApproachFrom EverandMinimally Invasive Surgery for Chronic Pain Management: An Evidence-Based ApproachGiorgio PietramaggioriNo ratings yet

- W.R. Klemm (Auth.) - Atoms of Mind - The - Ghost in The Machine - Materializes-Springer Netherlands (2011)Document371 pagesW.R. Klemm (Auth.) - Atoms of Mind - The - Ghost in The Machine - Materializes-Springer Netherlands (2011)El equipo de Genesis ProjectNo ratings yet

- The Power of Adventure in Your Hand: Product Catalog Volume 4 2019Document20 pagesThe Power of Adventure in Your Hand: Product Catalog Volume 4 2019Michael ShelbyNo ratings yet

- Baulkham Hills 2012 2U Prelim Yearly & SolutionsDocument11 pagesBaulkham Hills 2012 2U Prelim Yearly & SolutionsYe ZhangNo ratings yet

- 15Document20 pages15Allen Rey YeclaNo ratings yet

- Nozzle Loads - Part 2 - Piping-EngineeringDocument3 pagesNozzle Loads - Part 2 - Piping-EngineeringShaikh AftabNo ratings yet

- 2.data Types Ver2Document56 pages2.data Types Ver2qwernasdNo ratings yet

- DLT Strand Jack Systems - 2.0 - 600 PDFDocument24 pagesDLT Strand Jack Systems - 2.0 - 600 PDFganda liftindoNo ratings yet

- Leading The Industry In: Solar Microinverter TechnologyDocument2 pagesLeading The Industry In: Solar Microinverter TechnologydukegaloNo ratings yet

- Safe Bearing Capacity of Soil - Based On Is: 6403 Sample CalculationDocument1 pageSafe Bearing Capacity of Soil - Based On Is: 6403 Sample CalculationSantosh ZunjarNo ratings yet

- Unit 6 - EarthingDocument26 pagesUnit 6 - Earthinggautam100% (1)

- 6100 SQ Lcms Data SheetDocument4 pages6100 SQ Lcms Data Sheet王皓No ratings yet

- Assigment Comouter Science BSCDocument3 pagesAssigment Comouter Science BSCutkarsh9978100% (1)

- Form 1 ExercisesDocument160 pagesForm 1 Exerciseskays MNo ratings yet

- Spesiikasi PerallatanDocument10 pagesSpesiikasi PerallatanRafi RaziqNo ratings yet

- Lec 4 Second Order Linear Differential EquationsDocument51 pagesLec 4 Second Order Linear Differential EquationsTarun KatariaNo ratings yet

- Creative Computing v06 n12 1980 DecemberDocument232 pagesCreative Computing v06 n12 1980 Decemberdarkstar314No ratings yet

- Semi Conductors: The Start of Information AgeDocument15 pagesSemi Conductors: The Start of Information AgeMarvin LabajoNo ratings yet

- B 1 1 4 Inplant Fluid FlowDocument5 pagesB 1 1 4 Inplant Fluid FlowBolívar AmoresNo ratings yet

- Demag KBK Alu Enclosed Track SystemDocument2 pagesDemag KBK Alu Enclosed Track SystemMAGSTNo ratings yet

- T8 - Energetics IDocument28 pagesT8 - Energetics II Kadek Irvan Adistha PutraNo ratings yet

- Hiley TableDocument5 pagesHiley TableHanafiahHamzahNo ratings yet

- HST TrainingDocument11 pagesHST TrainingRamesh BabuNo ratings yet

- Plate - 3 (FLOT)Document2 pagesPlate - 3 (FLOT)patrick dgNo ratings yet

- Cable Sizing CalculationDocument72 pagesCable Sizing CalculationHARI my songs100% (1)

- LTE Rach ProcedureDocument4 pagesLTE Rach ProcedureDeepak JammyNo ratings yet

- ML Observability Build Vs Buy Download Guide 1689038317Document31 pagesML Observability Build Vs Buy Download Guide 1689038317rastrol7No ratings yet

- Fahad H. Ahmad (+92 323 509 4443) : Kinetic Particle Theory (5070 Multiple Choice Questions)Document51 pagesFahad H. Ahmad (+92 323 509 4443) : Kinetic Particle Theory (5070 Multiple Choice Questions)Ali AshrafNo ratings yet

- Caterpillar Product Line 13Document7 pagesCaterpillar Product Line 13GenneraalNo ratings yet

- Number Patterns and SequencesDocument10 pagesNumber Patterns and SequencesMohamed Hawash80% (5)

- Microgrid Modeling and Grid Interconnection StudiesDocument71 pagesMicrogrid Modeling and Grid Interconnection StudiesVeeravasantharao BattulaNo ratings yet