Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Article 300A Case

Uploaded by

Kuldeep SinghOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Article 300A Case

Uploaded by

Kuldeep SinghCopyright:

Available Formats

AMBITION LAW INSTITUTE

CONSTITUTION OF INDIA

ARTICLE 300-A

Sukh Dutt Ratra and Ors. vs. State of Himachal Pradesh and Ors., (2022) 7 SCC 508

Facts

Sukh Dutt Ratra and Bhagat Ram (hereafter 'Appellants') claim to be owners of land2 situated at Mauzal

Sarol Basach, Tehsil Pachhad, District Sirmour, Himachal Pradesh (hereafter 'subject land'). The Re-

spondent-State utilised the subject land and adjoining lands for the construction of the 'Narag Fagla

Road' in 1972-73, but allegedly no land acquisition proceedings were initiated, nor compensation given

to the Appellants or owners of the adjoining land.

Pursuant to a judgment by the Himachal Pradesh High Court3 (hereafter 'High Court') directing the

State to initiate land acquisition proceedings, a notification Under Section 4 of the Land Acquisition

Act, 1894 (hereafter 'Act') was issued on 16.10.2001 (published on 30.10.2001) and the award was

passed on 20.12.2001 fixing compensation at ` 30,000 per bigha. Proceedings Under Section 18 of the

Act for enhancement of compensation, were initiated by ten neighbouring land owners (Mata Ram and

others), whose lands were similarly utilised for the construction of the same road and an award4 dated

04.10.2005 was passed by the reference court in their favour. It was held that the reference Petitioners

were entitled to enhanced compensation of ` 39,000 per bigha; solatium of 30% per annum on the

market value of the land; additional compensation at the rate of 12% per annum Under Section 23(1-A)

of the Act w.e.f. 16.10.2001 (date of issuance of notification Under Section 4) till the date of making of

the award by the Collector, i.e. 20.12.2001; and Under Section 28, interest of 9% per annum from

16.10.2001 for a period of one year, and thereafter 15% per annum, till date of payment. In 2009, the

High Court dismissed5 the appeal against this order by those claimants, who were seeking statutory

interest from the date of taking possession (rather than date of initiation of acquisition proceedings).

Similarly situated land owners, filed writ proceedings before the High Court: a writ petition filed by

one Anakh Singh, from the adjoining village was allowed by the High Court6 with the direction to

acquire lands of the writ Petitioners under the Act, with consequential benefits; subsequently other

similarly situated owners also received7 the benefit of these directions.

This led the Appellants to file a writ petition before the High Court in 2011, seeking compensation for

the subject land or initiation of acquisition proceedings under the Act. Relying on a Full bench deci-

sion8 of the High Court, it was held in the impugned judgment that the matter involved disputed

questions of law and fact for determination on the starting point of limitation, which could not be

adjudicated in writ proceedings. The writ petition was disposed of, with liberty to file a civil suit in

accordance with law. Aggrieved, the Appellants have approached this Court through these appeals.

Held, while allowing the appeal

“1. While the right to property is no longer a fundamental right, it is pertinent to note that at the time of

dispossession of the subject land, this right was still included in Part III of the Constitution. The right

against deprivation of property unless in accordance with procedure established by law, continues to be

a constitutional right under Article 300-A.

2. It is the cardinal principle of the Rule of law, that nobody can be deprived of liberty or property

OUR WEBSITE BUY BEST BARE ACTs. WE ARE ALSO ON

ambitionlawinstitute.com Ambitionpublications.com

without due process, or authorization of law. Further, in several judgments, this Court has repeatedly

held that rather than enjoying a wider bandwidth of lenience, the State often has a higher responsibility

in demonstrating that it has acted within the confines of legality, and therefore, not tarnished the basic

principle of the Rule of law.

3. There is a welter of precedents on delay and laches which conclude either way-as contended by both

sides in the present dispute-however, the specific factual matrix compels this Court to weigh in favour

of the Appellant-land owners. The State cannot shield itself behind the ground of delay and laches in

such a situation; there cannot be a 'limitation' to doing justice.

4. The facts of the present case reveal that the State has, in a clandestine and arbitrary manner, actively

tried to limit disbursal of compensation as required by law, only to those for which it was specifically

prodded by the courts, rather than to all those who are entitled. This arbitrary action, which is also

violative of the Appellants' prevailing Article 31 right (at the time of cause of action), undoubtedly

warranted consideration, and intervention by the High Court, under its Article 226 jurisdiction.

5. The State has merely averred to the Appellants' alleged verbal consent or the lack of objection, but

has not placed any material on record to substantiate this plea. Further, the State was unable to produce

any evidence indicating that the land of the Appellants had been taken over or acquired in the manner

known to law, or that they had ever paid any compensation. It is pertinent to note that this was the

State's position, and subsequent findings of the High Court in 2007 as well, in the other writ proceed-

ings.

6. This Court is also not moved by the State's contention that since the property is not adjoining to that

of the Appellants, it disentitles them from claiming benefit on the ground of parity. Despite it not being

adjoining (which is admitted in the rejoinder affidavit filed by the Appellants), it is clear that the subject

land was acquired for the same reason-construction of the Narag Fagla Road, in 1972-73, and much

like the claimants before the reference court, these Appellants too were illegally dispossessed without

following due process of law, thus resulting in violation of Article 31 and warranting the High Court's

intervention under Article 226 jurisdiction. In the absence of written consent to voluntarily give up

their land, the Appellants were entitled to compensation in terms of law.

7. In view of this Court's extraordinary jurisdiction under Article 136 and 142 of the Constitution, the

State is directed to treat the subject lands as a deemed acquisition and appropriately disburse compen-

sation to the Appellants in the same terms as the order of the reference court. The Respondent-State is

directed, consequently to ensure that the appropriate Land Acquisition Collector computes the com-

pensation, and disburses it to the Appellants, within four months.

8. The impugned order of the High Court is set aside. Appeal allowed.

OUR WEBSITE BUY BEST BARE ACTs. WE ARE ALSO ON

ambitionlawinstitute.com Ambitionpublications.com

You might also like

- California Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionFrom EverandCalifornia Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Simple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaFrom EverandSimple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Dispossession of Property-Human & Constitutional RightDocument8 pagesDispossession of Property-Human & Constitutional RightSankanna VijaykumarNo ratings yet

- Chitturi - Subbanna - Vs - Kudapa - Subbanna - and - Ors - 18121s640254COM154862Document21 pagesChitturi - Subbanna - Vs - Kudapa - Subbanna - and - Ors - 18121s640254COM154862Ryan MichaelNo ratings yet

- Order 26 Rule 9 of CPCDocument6 pagesOrder 26 Rule 9 of CPCPriya R50% (2)

- Contempt Petition NewDocument5 pagesContempt Petition NewKeshav JindalNo ratings yet

- Court Sets Aside Grant of Mining LeaseDocument3 pagesCourt Sets Aside Grant of Mining Leasesunny333No ratings yet

- TPADocument3 pagesTPASumit KalyaniNo ratings yet

- Caltex vs. Palomar promotional scheme rulingDocument7 pagesCaltex vs. Palomar promotional scheme rulingPat P. MonteNo ratings yet

- Sadashivaiah and Ors. Vs State of Karnataka and Ors. On 26 August, 2003Document12 pagesSadashivaiah and Ors. Vs State of Karnataka and Ors. On 26 August, 2003Manjunath ShadakshariNo ratings yet

- Special Land Acquisition Officer V Karigowda EditedDocument44 pagesSpecial Land Acquisition Officer V Karigowda EditedAntra AzadNo ratings yet

- Hari Singh - Written ArgumentsDocument16 pagesHari Singh - Written Argumentsvaibhav kharbandaNo ratings yet

- lcDocument3 pageslcaakthelegalegendsNo ratings yet

- AIR 2008 SC 901 Revenue Records Are Not Documents of TitleDocument4 pagesAIR 2008 SC 901 Revenue Records Are Not Documents of TitleSridhara babu. N - ಶ್ರೀಧರ ಬಾಬು. ಎನ್0% (1)

- Case Study DaryaoDocument7 pagesCase Study DaryaoPBNo ratings yet

- Illegal Dispossession Act - 2005 CA-16 of 2010Document18 pagesIllegal Dispossession Act - 2005 CA-16 of 2010Sharjeel Umer0% (1)

- RTC Jurisdiction Over Land Registration CaseDocument13 pagesRTC Jurisdiction Over Land Registration CaseIvan Montealegre ConchasNo ratings yet

- S. 10 - Deduction of Collection Charge in Order To Recovery of Dues As Arrears of Land Revenue Would Be PermissibleDocument41 pagesS. 10 - Deduction of Collection Charge in Order To Recovery of Dues As Arrears of Land Revenue Would Be PermissibleAnshul SinghNo ratings yet

- Chap 9Document13 pagesChap 9D Del SalNo ratings yet

- Civil CourtDocument16 pagesCivil CourtNandini SinghNo ratings yet

- Admin Digest 12 - 19 NewDocument16 pagesAdmin Digest 12 - 19 NewptbattungNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court upholds reopening of land acquisition caseDocument3 pagesSupreme Court upholds reopening of land acquisition caseShahi ShahilNo ratings yet

- Land Registration Case FinalityDocument8 pagesLand Registration Case FinalityJR C Galido IIINo ratings yet

- Equitorial Realty V Frogozo (2004)Document6 pagesEquitorial Realty V Frogozo (2004)Reyna RemultaNo ratings yet

- Citation Name: 2021 CLC 1738 QUETTA-HIGH-COURT-BALOCHISTANDocument38 pagesCitation Name: 2021 CLC 1738 QUETTA-HIGH-COURT-BALOCHISTANUzma GulNo ratings yet

- SC Judgment On Effect of Concurrent Finding of FactDocument13 pagesSC Judgment On Effect of Concurrent Finding of FactLatest Laws TeamNo ratings yet

- Arvind Singh So Late Haridwar Singh Proprietor of u050432COM104259Document5 pagesArvind Singh So Late Haridwar Singh Proprietor of u050432COM104259AnaghNo ratings yet

- EQUATORIAL V Sps DesiderioDocument7 pagesEQUATORIAL V Sps DesiderioRogie ToriagaNo ratings yet

- United Provinces v. Atiqa BegumDocument19 pagesUnited Provinces v. Atiqa BegumKirithika HariharanNo ratings yet

- China Bank Vs Ordinario DigestDocument2 pagesChina Bank Vs Ordinario Digestcmv mendozaNo ratings yet

- Mendoza Vs CaDocument7 pagesMendoza Vs CaPatNo ratings yet

- Rule 2 Case Digest - Joinder of Causes of ActionDocument3 pagesRule 2 Case Digest - Joinder of Causes of ActionRowena GallegoNo ratings yet

- Naguiat vs. IACDocument3 pagesNaguiat vs. IACJessa F. Austria-CalderonNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction of Civil Court in Agricultural Land DisputesDocument11 pagesJurisdiction of Civil Court in Agricultural Land DisputesSravyaNo ratings yet

- J 1968 3 SCR 662 AIR 1969 SC 78 22 STC 416 Rehanghalibkhan Gmailcom 20230411 113931 1 20Document20 pagesJ 1968 3 SCR 662 AIR 1969 SC 78 22 STC 416 Rehanghalibkhan Gmailcom 20230411 113931 1 20Rehan Ghalib KhanNo ratings yet

- WP 36544-2015 PDFDocument10 pagesWP 36544-2015 PDFponnilavanNo ratings yet

- Bhusawal Municipal Council Vs Nivrutti Ramchandra 2013Document6 pagesBhusawal Municipal Council Vs Nivrutti Ramchandra 2013Anubhav JainNo ratings yet

- Easementary Right in Land Cannot Extinguish Even After Acquisition 2005 SCDocument3 pagesEasementary Right in Land Cannot Extinguish Even After Acquisition 2005 SCSridhara babu. N - ಶ್ರೀಧರ ಬಾಬು. ಎನ್No ratings yet

- DATAR SWITCHGEARS VS TATA FINANCE ARBITRATION CASE STUDYDocument15 pagesDATAR SWITCHGEARS VS TATA FINANCE ARBITRATION CASE STUDYNimya RoyNo ratings yet

- Constitutionality - of - The - Doctrine - of Adverse Possession PDFDocument8 pagesConstitutionality - of - The - Doctrine - of Adverse Possession PDFTommy MogakaNo ratings yet

- Executing Court Should Decide Obstructions Made To Delivery of Possession by Holding Whether Obstructor Is Bound by Decree or Not Air 2002 SC 251Document11 pagesExecuting Court Should Decide Obstructions Made To Delivery of Possession by Holding Whether Obstructor Is Bound by Decree or Not Air 2002 SC 251Sridhara babu. N - ಶ್ರೀಧರ ಬಾಬು. ಎನ್No ratings yet

- Landowners allowed to file late cross-objections in land acquisition caseDocument170 pagesLandowners allowed to file late cross-objections in land acquisition caseKumaramtNo ratings yet

- DefineDocument12 pagesDefinekirstyadriano3131No ratings yet

- 261 Shivashankara V HP Vedavyasa Char 29 Mar 2023 466500Document15 pages261 Shivashankara V HP Vedavyasa Char 29 Mar 2023 466500DhineshNo ratings yet

- Nabus Vs CA (Mariano Lim)Document2 pagesNabus Vs CA (Mariano Lim)cmv mendozaNo ratings yet

- Case Laws On LA ActDocument5 pagesCase Laws On LA ActPradnya Ram PNo ratings yet

- Rejection of Plaint Based Upon Plea of Limitation Is A Mixed Question of Fact and Shall Be Decided On MeritsDocument7 pagesRejection of Plaint Based Upon Plea of Limitation Is A Mixed Question of Fact and Shall Be Decided On MeritsSridhara babu. N - ಶ್ರೀಧರ ಬಾಬು. ಎನ್100% (1)

- Jayaram Mudaliar vs. Ayyaswami and OrsDocument15 pagesJayaram Mudaliar vs. Ayyaswami and OrsBrijbhan Singh RajawatNo ratings yet

- Nkojo Amooti V Kyazze 2 Ors (Civil Suit No 536 of 2012) 2013 UGHCLD 85 (26 November 2013)Document6 pagesNkojo Amooti V Kyazze 2 Ors (Civil Suit No 536 of 2012) 2013 UGHCLD 85 (26 November 2013)Fortune RaymondNo ratings yet

- Court Rules on Land Ownership DisputeDocument4 pagesCourt Rules on Land Ownership Disputeapril75No ratings yet

- Display PDFDocument9 pagesDisplay PDFspider webNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court rules on competing priorities between charge and mortgageDocument26 pagesSupreme Court rules on competing priorities between charge and mortgageKarishma MotlaNo ratings yet

- State of U.P. v. Sudhir Kumar Singh, 2020 SCC OnLine SC 847Document27 pagesState of U.P. v. Sudhir Kumar Singh, 2020 SCC OnLine SC 847arunimaNo ratings yet

- T Yunis V National Highways Authority of IndiaDocument4 pagesT Yunis V National Highways Authority of IndiaDevansh MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction CasesDocument25 pagesJurisdiction CasesAerwin AbesamisNo ratings yet

- Gurbux Singh vs. Bhooralal Order 2 Rule 2Document3 pagesGurbux Singh vs. Bhooralal Order 2 Rule 2Sidd ZeusNo ratings yet

- PPSRC v. Azania Bancorp LTDDocument12 pagesPPSRC v. Azania Bancorp LTDSAMWEL CHARLESNo ratings yet

- raschidDocument11 pagesraschidpvtNo ratings yet

- Ashutosh Sharma and Ors Reply 2multiDocument17 pagesAshutosh Sharma and Ors Reply 2multiNikhilparakhNo ratings yet

- Benami property disputeDocument5 pagesBenami property disputeAhmad Raza KhalidNo ratings yet

- Questionnaire For ThesisDocument5 pagesQuestionnaire For ThesisRamiz HassanNo ratings yet

- Incidentrequest Closed Monthly JunDocument250 pagesIncidentrequest Closed Monthly Junأحمد أبوعرفهNo ratings yet

- TerrSet TutorialDocument470 pagesTerrSet TutorialMoises Gamaliel Lopez Arias100% (1)

- DataSheet ULCAB300Document2 pagesDataSheet ULCAB300Yuri OliveiraNo ratings yet

- MR Khurram Chakwal 6kw Hybrid - 024627Document6 pagesMR Khurram Chakwal 6kw Hybrid - 024627Shahid HussainNo ratings yet

- IsotopesDocument35 pagesIsotopesAddisu Amare Zena 18BML0104No ratings yet

- Tax2win's Growth Strategy Through Comprehensive Tax SolutionsDocument6 pagesTax2win's Growth Strategy Through Comprehensive Tax SolutionsAhmar AyubNo ratings yet

- F INALITYp 3Document23 pagesF INALITYp 3api-3701467100% (1)

- Auditing Case 3Document12 pagesAuditing Case 3Kenny Mulvenna100% (6)

- DRW Questions 2Document16 pagesDRW Questions 2Natasha Elena TarunadjajaNo ratings yet

- Indian Standard: Methods For Sampling of Clay Building BricksDocument9 pagesIndian Standard: Methods For Sampling of Clay Building BricksAnonymous i6zgzUvNo ratings yet

- Somya Bhasin 24years Pune: Professional ExperienceDocument2 pagesSomya Bhasin 24years Pune: Professional ExperienceS1626No ratings yet

- Kneehab XP Instructions and UsageDocument16 pagesKneehab XP Instructions and UsageMVP Marketing and DesignNo ratings yet

- S3 Unseen PracticeDocument7 pagesS3 Unseen PracticeTanush GoelNo ratings yet

- Distributor AgreementDocument10 pagesDistributor Agreementsanket_hiremathNo ratings yet

- AOC AW INSP 010 Rev04 AOC Base Inspection ChecklistDocument6 pagesAOC AW INSP 010 Rev04 AOC Base Inspection ChecklistAddisuNo ratings yet

- United Nations Manual on Reimbursement for Peacekeeping EquipmentDocument250 pagesUnited Nations Manual on Reimbursement for Peacekeeping EquipmentChefe GaragemNo ratings yet

- As 3566.1-2002 Self-Drilling Screws For The Building and Construction Industries General Requirements and MecDocument7 pagesAs 3566.1-2002 Self-Drilling Screws For The Building and Construction Industries General Requirements and MecSAI Global - APAC0% (2)

- Application For Transmission of Shares / DebenturesDocument2 pagesApplication For Transmission of Shares / DebenturesCS VIJAY THAKURNo ratings yet

- Law On Sales: Perfection Stage Forms of Sale When Sale Is SimulatedDocument21 pagesLaw On Sales: Perfection Stage Forms of Sale When Sale Is SimulatedRalph ManuelNo ratings yet

- Simple Problem On ABC: RequiredDocument3 pagesSimple Problem On ABC: RequiredShreshtha VermaNo ratings yet

- Acquisition of SharesDocument3 pagesAcquisition of SharesChaudhary Mohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Combined SGMA 591Document46 pagesCombined SGMA 591Steve BallerNo ratings yet

- Plan & Elevation of Dog-Legged StaircaseDocument1 pagePlan & Elevation of Dog-Legged Staircasesagnik bhattacharjeeNo ratings yet

- A Study On Consumer Changing Buying Behaviour From Gold Jewellery To Diamond JewelleryDocument9 pagesA Study On Consumer Changing Buying Behaviour From Gold Jewellery To Diamond JewellerynehaNo ratings yet

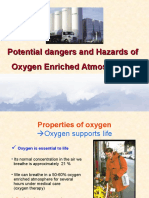

- OxygenDocument18 pagesOxygenbillllibNo ratings yet

- 2021 Subsector OutlooksDocument24 pages2021 Subsector OutlooksHungNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument29 pagesUntitledsav 1011100% (1)

- United States v. Bueno-Hernandez, 10th Cir. (2012)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Bueno-Hernandez, 10th Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pantangco DigestDocument2 pagesPantangco DigestChristine ZaldivarNo ratings yet