Professional Documents

Culture Documents

AI Essey Part 2

AI Essey Part 2

Uploaded by

Никола НаковOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

AI Essey Part 2

AI Essey Part 2

Uploaded by

Никола НаковCopyright:

Available Formats

We’re living during this paradigm shift where everyone’s thinking about the soulfulness, or relative

un-soulfulness, of A.I. he said.

I’ve been struggling with the question of how we might navigate technology’s role in the arts, and

A.I.’s nonfeeling, data-driven means of creation.

Or to ask it to write a scene in the style of a specific writer and, even with the odd phrases and weird

artifacts typical of A.I.-generated writing, hear an eerie sense of familiarity in the scene’s tone.

We’re living during this paradigm shift where everyone’s thinking about the soulfulness, or relative

un-soulfulness, of A.I. he said.

Lopatin’s work with A.I. owes at least a theoretical debt to the French composer Edgard Varèse, who

was bored by the limitations of acoustic instruments, and who, in 1936, described “the electronic” as

“our new liberating medium.” Varèse thought that only electronic instruments could effectively

“satisfy the dictates of that inner ear of the imagination,” and dismissed fears that these new modes

might challenge composition. “Anything new in music has always been called noise,” he wrote.

Lopatin finds most of the hand-wringing about A.I. to be silly. “It’s over, we’re all gonna die, the

machines are coming to get us,” he said, laughing. “That’s really boring. What’s more interesting for

me is seeing how A.I. fails.” He went on, “When it fails, which it does a lot right now, it creates these

insinuated arrangements that don’t sound anything like any music I’ve ever heard. It’s so broken that

I can only compare it to, like, the most extreme music I’ve ever heard in my life.”

A.I.’s wonkiness—all of these networks are still in their nascency—forced Lopatin to reëxamine his

most instinctive and well-worn habits. “It reminds me a lot of Paul Schrader’s transcendental-cinema

thing,” Lopatin said. “He always talks about how there are films that are formulaic and ones that

aren’t. The ones that aren’t do weird things with time. They dwell a little bit too long on the wrong

object, like a door after someone has passed through it. You’re usually following the person, but now

we’re staying on the door. That’s what A.I. is actually doing really well. What it’s not doing very well is

following the person.” He continued, “When I first started using A.I., I would basically just give it

metadata. I’d say, ‘I want you to make a Smashing Pumpkins song.’ It tries, and it can’t. That’s a lot

like me.”

“[I was considering] how impossible and futile it is to try to undo humanity’s mistakes, and what a

horrific situation it is to be stalked by the future. That [made] a huge impression on me, it’s been in

my music pretty much the entire time.”

He thinks current AI is something to be experimented with rather than a horrifying,

incomprehensible intellect.

We have so much to learn from this stuff right now: about its failure to compute, about arrangement

and incorrect choices, about lingering on an idea a little bit too long, about dissonant qualities in pop

music… not even to sample [it], but to really think about its form and apply it to your own writing.

I’ve been struggling with the question of how we might navigate technology’s role in the arts, and

A.I.’s nonfeeling, data-driven means of creation.

Or to ask it to write a scene in the style of a specific writer and, even with the odd phrases and weird

artifacts typical of A.I.-generated writing, hear an eerie sense of familiarity in the scene’s tone.

We’re living during this paradigm shift where everyone’s thinking about the soulfulness, or relative

un-soulfulness, of A.I. he said.

Lopatin’s work with A.I. owes at least a theoretical debt to the French composer Edgard Varèse, who

was bored by the limitations of acoustic instruments, and who, in 1936, described “the electronic” as

“our new liberating medium.” Varèse thought that only electronic instruments could effectively

“satisfy the dictates of that inner ear of the imagination,” and dismissed fears that these new modes

might challenge composition. “Anything new in music has always been called noise,” he wrote.

Lopatin finds most of the hand-wringing about A.I. to be silly. “It’s over, we’re all gonna die, the

machines are coming to get us,” he said, laughing. “That’s really boring. What’s more interesting for

me is seeing how A.I. fails.” He went on, “When it fails, which it does a lot right now, it creates these

insinuated arrangements that don’t sound anything like any music I’ve ever heard. It’s so broken that

I can only compare it to, like, the most extreme music I’ve ever heard in my life.”

A.I.’s wonkiness—all of these networks are still in their nascency—forced Lopatin to reëxamine his

most instinctive and well-worn habits. “It reminds me a lot of Paul Schrader’s transcendental-cinema

thing,” Lopatin said. “He always talks about how there are films that are formulaic and ones that

aren’t. The ones that aren’t do weird things with time. They dwell a little bit too long on the wrong

object, like a door after someone has passed through it. You’re usually following the person, but now

we’re staying on the door. That’s what A.I. is actually doing really well. What it’s not doing very well is

following the person.” He continued, “When I first started using A.I., I would basically just give it

metadata. I’d say, ‘I want you to make a Smashing Pumpkins song.’ It tries, and it can’t. That’s a lot

like me.”

“[I was considering] how impossible and futile it is to try to undo humanity’s mistakes, and what a

horrific situation it is to be stalked by the future. That [made] a huge impression on me, it’s been in

my music pretty much the entire time.”

He thinks current AI is something to be experimented with rather than a horrifying,

incomprehensible intellect.

We have so much to learn from this stuff right now: about its failure to compute, about arrangement

and incorrect choices, about lingering on an idea a little bit too long, about dissonant qualities in pop

music… not even to sample [it], but to really think about its form and apply it to your own writing.

I’ve been struggling with the question of how we might navigate technology’s role in the arts, and

A.I.’s nonfeeling, data-driven means of creation.

Or to ask it to write a scene in the style of a specific writer and, even with the odd phrases and weird

artifacts typical of A.I.-generated writing, hear an eerie sense of familiarity in the scene’s tone.

We’re living during this paradigm shift where everyone’s thinking about the soulfulness, or relative

un-soulfulness, of A.I. he said.

Lopatin’s work with A.I. owes at least a theoretical debt to the French composer Edgard Varèse, who

was bored by the limitations of acoustic instruments, and who, in 1936, described “the electronic” as

“our new liberating medium.” Varèse thought that only electronic instruments could effectively

“satisfy the dictates of that inner ear of the imagination,” and dismissed fears that these new modes

might challenge composition. “Anything new in music has always been called noise,” he wrote.

Lopatin finds most of the hand-wringing about A.I. to be silly. “It’s over, we’re all gonna die, the

machines are coming to get us,” he said, laughing. “That’s really boring. What’s more interesting for

me is seeing how A.I. fails.” He went on, “When it fails, which it does a lot right now, it creates these

insinuated arrangements that don’t sound anything like any music I’ve ever heard. It’s so broken that

I can only compare it to, like, the most extreme music I’ve ever heard in my life.”

A.I.’s wonkiness—all of these networks are still in their nascency—forced Lopatin to reëxamine his

most instinctive and well-worn habits. “It reminds me a lot of Paul Schrader’s transcendental-cinema

thing,” Lopatin said. “He always talks about how there are films that are formulaic and ones that

aren’t. The ones that aren’t do weird things with time. They dwell a little bit too long on the wrong

object, like a door after someone has passed through it. You’re usually following the person, but now

we’re staying on the door. That’s what A.I. is actually doing really well. What it’s not doing very well is

following the person.” He continued, “When I first started using A.I., I would basically just give it

metadata. I’d say, ‘I want you to make a Smashing Pumpkins song.’ It tries, and it can’t. That’s a lot

like me.”

“[I was considering] how impossible and futile it is to try to undo humanity’s mistakes, and what a

horrific situation it is to be stalked by the future. That [made] a huge impression on me, it’s been in

my music pretty much the entire time.”

He thinks current AI is something to be experimented with rather than a horrifying,

incomprehensible intellect.

We have so much to learn from this stuff right now: about its failure to compute, about arrangement

and incorrect choices, about lingering on an idea a little bit too long, about dissonant qualities in pop

music… not even to sample [it], but to really think about its form and apply it to your own writing.

I’ve been struggling with the question of how we might navigate technology’s role in the arts, and

A.I.’s nonfeeling, data-driven means of creation.

Or to ask it to write a scene in the style of a specific writer and, even with the odd phrases and weird

artifacts typical of A.I.-generated writing, hear an eerie sense of familiarity in the scene’s tone.

You might also like

- The Creative Habit: Learn It and Use It for LifeFrom EverandThe Creative Habit: Learn It and Use It for LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (82)

- The Story of The Streets - Skinner MikeDocument156 pagesThe Story of The Streets - Skinner MikeAnonymous yP0h8iTCzNo ratings yet

- AnneboyerthetwothousandsDocument61 pagesAnneboyerthetwothousandsamboyer100% (3)

- 2017 8th Grade ELADocument15 pages2017 8th Grade ELARania MohammedNo ratings yet

- Matthew Hutson, "Artificial Intelligence and Musical Creativity: Computing Beethoven's Tenth"Document48 pagesMatthew Hutson, "Artificial Intelligence and Musical Creativity: Computing Beethoven's Tenth"MIT Comparative Media Studies/WritingNo ratings yet

- Powers of Two: How Relationships Drive CreativityFrom EverandPowers of Two: How Relationships Drive CreativityRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (12)

- The Theatre of Pina Bausch. Hoghe PDFDocument13 pagesThe Theatre of Pina Bausch. Hoghe PDFSofía RuedaNo ratings yet

- Achievers B1 (Eighth)Document2 pagesAchievers B1 (Eighth)Freddy Montiel100% (2)

- What Can AI AnalaysisDocument4 pagesWhat Can AI AnalaysisНикола НаковNo ratings yet

- The Economist - How AI Is Transforming The Creative IndustriesDocument3 pagesThe Economist - How AI Is Transforming The Creative Industriesduy phamNo ratings yet

- Continue Online Part One: Memories: Continue Online, #1From EverandContinue Online Part One: Memories: Continue Online, #1Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Cage DiaryDocument2 pagesCage DiaryRocio Montoya UribeNo ratings yet

- DELILLO OdlomciDocument3 pagesDELILLO OdlomcianglistikansNo ratings yet

- Brass Band and Oxbridge Mourners at WH Auden's Funeral - Archive, 1973Document3 pagesBrass Band and Oxbridge Mourners at WH Auden's Funeral - Archive, 1973missr2798No ratings yet

- JodorowskyDocument15 pagesJodorowskykluckalicaNo ratings yet

- Alone Together Sherry Turckle IntroDocument10 pagesAlone Together Sherry Turckle IntroAnnaBentesNo ratings yet

- Gonzalez-Torres, Felix. Interview by Maurizio Cattelan. Mousse Magazine (Italy) 9 Summer 2007 - 40 - 43.Document5 pagesGonzalez-Torres, Felix. Interview by Maurizio Cattelan. Mousse Magazine (Italy) 9 Summer 2007 - 40 - 43.Taylor WorleyNo ratings yet

- The New Poem-Making MachineryDocument14 pagesThe New Poem-Making MachineryCherane ChristopherNo ratings yet

- In Lucem Solaria - Birth of Queen Bee: In Lucem Solaria, #1From EverandIn Lucem Solaria - Birth of Queen Bee: In Lucem Solaria, #1No ratings yet

- Frankenstein EquationDocument17 pagesFrankenstein EquationIan BeardsleyNo ratings yet

- The Dream of A.IDocument5 pagesThe Dream of A.Iruth varquezNo ratings yet

- The Theatre of Pina Bausch - HOGHEDocument13 pagesThe Theatre of Pina Bausch - HOGHELenz21No ratings yet

- Reaction Paper: John Cage InterviewsDocument6 pagesReaction Paper: John Cage InterviewsTricia TuanquinNo ratings yet

- The Writer S HandbookDocument750 pagesThe Writer S HandbookJuan FolinoNo ratings yet

- Tarkovskyon NostalghiaDocument3 pagesTarkovskyon NostalghiaArockiya DanielNo ratings yet

- Neo FuturismDocument15 pagesNeo FuturismDaniel DempseyNo ratings yet

- Overheard: Steven SoderberghDocument8 pagesOverheard: Steven Soderberghsunder_vasudevanNo ratings yet

- Destroy Civilisation: The Adventures of an Anarchist Pop Punk Band From ParisFrom EverandDestroy Civilisation: The Adventures of an Anarchist Pop Punk Band From ParisNo ratings yet

- Elizabeth Gilbert - Nurturing Creativity (Answer Key)Document7 pagesElizabeth Gilbert - Nurturing Creativity (Answer Key)Bernadette AwenNo ratings yet

- (Transcript) The Role of Arts & Culture in An Open SocietyDocument2 pages(Transcript) The Role of Arts & Culture in An Open SocietyJBNo ratings yet

- Indianapolismonthlywritingsample2 FrazierDocument3 pagesIndianapolismonthlywritingsample2 Frazierapi-313074174No ratings yet

- Art Practice As ResearchDocument6 pagesArt Practice As ResearchDanMichael ReyesNo ratings yet

- Math237 Paper 6Document5 pagesMath237 Paper 6Tania PrastyaNo ratings yet

- Art206 Week 3Document4 pagesArt206 Week 3Tharindu DissanayakeNo ratings yet

- Leviathan (Presented at The Jvaskyla Festival, 2002)Document20 pagesLeviathan (Presented at The Jvaskyla Festival, 2002)simoningsNo ratings yet

- SOC263 Lecture 8Document3 pagesSOC263 Lecture 8Iván SánchezNo ratings yet

- Can I Have Your Attention Please?Document41 pagesCan I Have Your Attention Please?scarschwartz100% (2)

- Quote JournalDocument4 pagesQuote Journaleswara20No ratings yet

- Essay Zolghadr NieuwDocument6 pagesEssay Zolghadr NieuwOliver HullNo ratings yet

- Sentiments Analysis of Amazon Reviews Dataset by Using Machine LearningDocument9 pagesSentiments Analysis of Amazon Reviews Dataset by Using Machine LearningIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Ewa SmiDocument55 pagesEwa SmiCasteloMXNo ratings yet

- Memory Testing - MBIST, BIRA - BISR - Algorithms, Self Repair MechanismDocument10 pagesMemory Testing - MBIST, BIRA - BISR - Algorithms, Self Repair MechanismSpruha JoshiNo ratings yet

- Android InitDocument5 pagesAndroid InitappleappsNo ratings yet

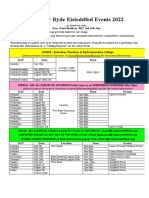

- Dates For Ryde Eisteddfod Events 2022Document2 pagesDates For Ryde Eisteddfod Events 2022DJNo ratings yet

- Java Script KeygenDocument6 pagesJava Script Keygen737448 SVNo ratings yet

- BIM-GPT: A Prompt-Based Virtual Assistant Framework For BIM Information RetrievalDocument35 pagesBIM-GPT: A Prompt-Based Virtual Assistant Framework For BIM Information RetrievalBien Pham HuuNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Exercise 3: Latches, Flip-Flops, and RegistersDocument6 pagesLaboratory Exercise 3: Latches, Flip-Flops, and RegistersTuân PhạmNo ratings yet

- Ibibio PeopleDocument4 pagesIbibio PeopleSarvagya100% (1)

- Cambridge IGCSE: Biology For Examination From 2023Document4 pagesCambridge IGCSE: Biology For Examination From 2023Valentina PorrasNo ratings yet

- Basic English Grammar: By: Ashwini H Asst - Prof of English Department of Humanities Canara Engineering CollegeDocument20 pagesBasic English Grammar: By: Ashwini H Asst - Prof of English Department of Humanities Canara Engineering CollegeDhanush ShastryNo ratings yet

- First Summative Test-English 8 Modules 1 and 2Document3 pagesFirst Summative Test-English 8 Modules 1 and 2CHRISTIAN ChuaNo ratings yet

- Liye - Info Let Us C by Yashavant Kanetkar PDF Free Download Democratic PRDocument1 pageLiye - Info Let Us C by Yashavant Kanetkar PDF Free Download Democratic PRLoowen DxNo ratings yet

- Soal Latihan GMDSSDocument69 pagesSoal Latihan GMDSSRudi Anton SinagaNo ratings yet

- Passive Causative: Have/Get Something DoneDocument6 pagesPassive Causative: Have/Get Something DoneMañanaMatutinaNo ratings yet

- Kevin Hogan - Breaking Through The 8 Barriers To CommunicationDocument1,073 pagesKevin Hogan - Breaking Through The 8 Barriers To Communicationteacherignou0% (2)

- Soal Bahasa Inggris Dan Matematika Kelas X - XiDocument5 pagesSoal Bahasa Inggris Dan Matematika Kelas X - XiBidenk AzaNo ratings yet

- Data Analysis Method: (Qualitative)Document25 pagesData Analysis Method: (Qualitative)lili filmNo ratings yet

- Christmas Time Vocabulary ExercisesDocument2 pagesChristmas Time Vocabulary Exercisesveronica sanchezNo ratings yet

- Letter To EditorDocument16 pagesLetter To EditorAleksandra SpasicNo ratings yet

- Chanski and Ellis - Peer FeedbackDocument7 pagesChanski and Ellis - Peer Feedbacktjohns56No ratings yet

- Tos Template Arpan 1Document25 pagesTos Template Arpan 1florence s. fernandezNo ratings yet

- Year 6 Name: Year: A. Simple Present Tense - Fill in The Blanks With The Correct Form of The Verbs in Brackets. (5 Marks)Document5 pagesYear 6 Name: Year: A. Simple Present Tense - Fill in The Blanks With The Correct Form of The Verbs in Brackets. (5 Marks)jonny boyNo ratings yet

- LQG 15 HSR 10 J 02Document3 pagesLQG 15 HSR 10 J 02David AlexNo ratings yet

- Cbea-English Q1 No 7Document3 pagesCbea-English Q1 No 7Kat Causaren LandritoNo ratings yet

- English Class 1Document25 pagesEnglish Class 1Dinesh KagNo ratings yet

- Why Hippos Have No Hair: Basilio GimoDocument10 pagesWhy Hippos Have No Hair: Basilio GimoPrecious ChanaiwaNo ratings yet

- How To Download Scribd Documents Without Download Option - FilelemDocument10 pagesHow To Download Scribd Documents Without Download Option - FilelemRoy Andrew GarciaNo ratings yet