Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Shioji-Vs-Harvey-43-Phil-333-G-R-No-L-18940-April-27-1922

Shioji-Vs-Harvey-43-Phil-333-G-R-No-L-18940-April-27-1922

Uploaded by

Karen ValdezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Shioji-Vs-Harvey-43-Phil-333-G-R-No-L-18940-April-27-1922

Shioji-Vs-Harvey-43-Phil-333-G-R-No-L-18940-April-27-1922

Uploaded by

Karen ValdezCopyright:

Available Formats

Shioji Vs Harvey, 43 Phil 333, G.R. No.

L-18940, April 27, 1922

Facts:

In cause No. 19471 of the Court of First Instance of Manila, wherein S. Shioji was plaintiff, and

the Toyo Kisen Kaisah and the Pacific Mail Steamship Co., were defendants, judgment was

rendered on October 31, 1920, by Judge Concepcion presiding in the second branch of the

court, in favor of the plaintiff and against the defendants. Thereafter, the defendants duly

perfected an appeal by way of bill of exceptions, to the Supreme Court of the Philippine Islands

filed on February 16, 1922.

The countermove of the respondents in the injunction proceedings pending the Court of First

Instance was to file a complaint in prohibition in the Supreme Court, to compel the respondent

Judge of First Instance to desist from interfering with the execution of the judgment in case No.

19471 of the Court of First Instance of Manila and to issue an order revoking the previously

promulgated by him. The preliminary injunction prayed for as an incident to the complaint in

prohibition was immediately issued by the Supreme Court, and has been complied with by the

respondents herein. Counsel Petitioner herein moves for judgment on the pleadings.

Issue:

1. Whether or not the Judge of First Instance may assume the jurisdiction to interpret and

review judgment and order of the Supreme Court, and to obstruct the enforcement of the

decisions of the appellate court.

2. Whether or not Rule 24 (a) is in conflict with any law of the United States or of the

Philippine Islands.

Ruling:

With regards to the First issue:

No. The only function of a lower court, when the judgment of a high court is returned, is the

ministerial one, the issuing of the order of execution, and that lower court is without

supervisory jurisdiction to interpret or to reverse the judgment of the higher court as it would

seem to be superfluous. A judge of a lower court cannot enforce different decrees than those

rendered by the superior court. The Supreme Court of the Philippine Island is expressly

authorized by statute to make rules for regulation of its practice and the conduct of its

business. Section 28 of the Judiciary Act (No. 136), grants to the members of the Supreme Court

the power to "make all necessary rules for orderly procedure in Supreme Court . . . in

accordance with the provisions of the Code of Civil Procedure, which rules shall be . . . binding

upon the several courts."

With regards to the First Issue:

No, Rule 24 (a) is not in conflict with any law of the United States or of the Philippines, but is a

necessary rule for orderly procedure and for regulating the conduct of business in Supreme

Court. It is a rule which relates to a matter of practice and procedure over which the Legislature

has not exercised its power. It is a rule which does not operate to deprive a party of any

statutory right. It is a rule in harmony with judicial practice and procedure over which the

Legislature has not exercised its power. It is a rule which does not operate to deprive a party of

any statutory right. It is a rule in harmony with judicial practice and procedure and essential to

the existence of the courts. And, finally, it is a rule which must be enforced according to the

discretion of the court. Independent of any statutory provision, the court asserts that every

court has inherent power to do all things reasonably necessary for the administration of justice

within the scope of its jurisdiction.

You might also like

- Agpalo Chap - II AdmissionToPracticeDocument6 pagesAgpalo Chap - II AdmissionToPracticeGelo MVNo ratings yet

- Solar Entertainment v. Hon. HowDocument1 pageSolar Entertainment v. Hon. Howvallie21100% (1)

- Unitrust Devt Bank vs. CaoibesDocument1 pageUnitrust Devt Bank vs. CaoibesEderic ApaoNo ratings yet

- Plus Builders v. Revilla Case Digest LEGAL ETHICSDocument1 pagePlus Builders v. Revilla Case Digest LEGAL ETHICSColeenNo ratings yet

- Residence PermitDocument12 pagesResidence PermitTendayi K ChiurekiNo ratings yet

- trsl0215 0215web PDFDocument2 pagestrsl0215 0215web PDFJunior Francisco QuijanoNo ratings yet

- Case Digest - Adan vs. TacordaDocument4 pagesCase Digest - Adan vs. TacordaAnnabelle AriolaNo ratings yet

- Ysip v. Municipality of Cabiao, Nueva Ecija (Construction of Election Laws)Document2 pagesYsip v. Municipality of Cabiao, Nueva Ecija (Construction of Election Laws)kjhenyo218502No ratings yet

- 335 Landerio Demafiles v. ComelecDocument2 pages335 Landerio Demafiles v. ComelecCarissa CruzNo ratings yet

- Castelo Vs Atty ChingDocument3 pagesCastelo Vs Atty Chingxeileen08No ratings yet

- Anonymous Complaint Against Presiding Judge Analie CDocument1 pageAnonymous Complaint Against Presiding Judge Analie CChristine LaguraNo ratings yet

- Facts:: Hacienda Luisita Inc Vs Luisita Industrial Park Corp, Gr. 171101Document6 pagesFacts:: Hacienda Luisita Inc Vs Luisita Industrial Park Corp, Gr. 171101Nikki SiaNo ratings yet

- People Vs SantitoDocument7 pagesPeople Vs SantitoAndrew M. AcederaNo ratings yet

- Case 25 To 34Document11 pagesCase 25 To 34Mitchi BarrancoNo ratings yet

- 223 Scra 378 PaleDocument2 pages223 Scra 378 Paleczabina fatima delicaNo ratings yet

- Cases Legal EthicsDocument57 pagesCases Legal EthicsPipoy AmyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 25 Legal Reasoning 2011 Christopher Enright PDFDocument21 pagesChapter 25 Legal Reasoning 2011 Christopher Enright PDFPiayaNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics 1Document7 pagesLegal Ethics 1ChristineLilyChinNo ratings yet

- Joselano Guevarra Vs Atty. Eala DigestedDocument2 pagesJoselano Guevarra Vs Atty. Eala DigestedJanskie Mejes Bendero LeabrisNo ratings yet

- 13 14 DigestDocument3 pages13 14 DigestDavid_0752No ratings yet

- Paredes V GopencoDocument2 pagesParedes V Gopencocmv mendozaNo ratings yet

- Garcia vs. Comelec, GR 111230, September 30, 1994Document32 pagesGarcia vs. Comelec, GR 111230, September 30, 1994vj hernandezNo ratings yet

- LMT UP BRI Legal and Judicial Ethics and Practical ExercisesDocument13 pagesLMT UP BRI Legal and Judicial Ethics and Practical ExerciseslmcrsNo ratings yet

- G.R. Nos. 115044 - 117263 - Lim v. PacquingDocument30 pagesG.R. Nos. 115044 - 117263 - Lim v. PacquingArvhie SantosNo ratings yet

- 2 - Bir Ruling No. 517-11Document5 pages2 - Bir Ruling No. 517-11Gino Alejandro SisonNo ratings yet

- PFR ReviewerDocument2 pagesPFR Reviewerluis capulongNo ratings yet

- Busmente DigestDocument3 pagesBusmente DigestRoyce Ann PedemonteNo ratings yet

- Ethics Digest Canon 4Document10 pagesEthics Digest Canon 4Jean Monique Oabel-Tolentino100% (1)

- Socorro vs. Van Wilsen G.R. No. 193707Document7 pagesSocorro vs. Van Wilsen G.R. No. 193707vj hernandezNo ratings yet

- NHA v. CA (GR No. 128064, March 1 2004)Document3 pagesNHA v. CA (GR No. 128064, March 1 2004)Ashley Kate PatalinjugNo ratings yet

- Aguirre v. ReyesDocument2 pagesAguirre v. ReyesJoesil Dianne SempronNo ratings yet

- Barbuco vs. Atty. Beltran FactsDocument2 pagesBarbuco vs. Atty. Beltran FactsKimberly Rose PadillaNo ratings yet

- Buenaflor Vs RamirezDocument2 pagesBuenaflor Vs RamirezGillian Caye Geniza Briones100% (1)

- Obligations & Contracts: By: Atty. Joselito Julius B. FloresDocument134 pagesObligations & Contracts: By: Atty. Joselito Julius B. FloresHULAR REINANo ratings yet

- Canon XIV - Case DigestDocument3 pagesCanon XIV - Case DigestJoshua RiveraNo ratings yet

- Canon 3 To 5 Cases For Legal EthicsDocument22 pagesCanon 3 To 5 Cases For Legal EthicsLoucille Abing LacsonNo ratings yet

- Baluyot V HolganzaDocument2 pagesBaluyot V HolganzaMarioneMaeThiam100% (1)

- Who May Practice Law in The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesWho May Practice Law in The PhilippinesSamuel Mangetag jr100% (1)

- Lintag v. NPCDocument1 pageLintag v. NPCPrincess AyomaNo ratings yet

- Festejo VDocument4 pagesFestejo VAbegail De LeonNo ratings yet

- Embido v. SalvadorDocument2 pagesEmbido v. SalvadorLDNo ratings yet

- Cesar L. Lantoria Vs Atty. Irineo L. Bunyi FactsDocument3 pagesCesar L. Lantoria Vs Atty. Irineo L. Bunyi FactsLu CasNo ratings yet

- People vs. PintoDocument17 pagesPeople vs. PintoKaren CueNo ratings yet

- Quimpo V MendozaDocument7 pagesQuimpo V Mendozadar0800% (1)

- Cpra Vs CPR Comparison of CPR and CpraDocument17 pagesCpra Vs CPR Comparison of CPR and Cpracatceo1111No ratings yet

- Arban vs. BorjaDocument1 pageArban vs. BorjamonjekatreenaNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law CoachingDocument11 pagesCriminal Law CoachingmeerahNo ratings yet

- Carandang vs. RamirezDocument3 pagesCarandang vs. RamirezI am PowerNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics CasesDocument108 pagesLegal Ethics CasesChristine RozulNo ratings yet

- 01 - Uy Vs Contreras - DigestDocument2 pages01 - Uy Vs Contreras - DigestannmirandaNo ratings yet

- Freeman v. Reyes AC No. 6246, November 15, 2011 Marites E. Freeman, Complainant, vs. Atty. Zenaida P. Reyes, Respondent. Facts of The CaseDocument2 pagesFreeman v. Reyes AC No. 6246, November 15, 2011 Marites E. Freeman, Complainant, vs. Atty. Zenaida P. Reyes, Respondent. Facts of The CaseChloe RuizNo ratings yet

- U.S Vs TamparongDocument11 pagesU.S Vs TamparongAngelyn SusonNo ratings yet

- Trial Memorandum BuenoDocument3 pagesTrial Memorandum BuenoEfie LumanlanNo ratings yet

- Conrado Lopez v. Atty. Mata, Atty. Sentillas, and Atty. Abellana AC No. 9334 July 28, 2020 FactsDocument2 pagesConrado Lopez v. Atty. Mata, Atty. Sentillas, and Atty. Abellana AC No. 9334 July 28, 2020 FactsJoesil Dianne SempronNo ratings yet

- ANGARA Vs SANDIGANBAYAN CASE DIGESTDocument9 pagesANGARA Vs SANDIGANBAYAN CASE DIGESTJoyciie ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Microsoft Corporation v. Samir (G.r. No. 205800 September 10, 2014)Document5 pagesMicrosoft Corporation v. Samir (G.r. No. 205800 September 10, 2014)Ei BinNo ratings yet

- Azor v. BeltranDocument2 pagesAzor v. BeltranMichaelDemphNagaNo ratings yet

- Shioji Vs Harvey DigestDocument1 pageShioji Vs Harvey DigestKitsRelojoNo ratings yet

- Shioji Vs Harvey 43 Phil 333Document8 pagesShioji Vs Harvey 43 Phil 333MykaNo ratings yet

- 1.1. Shioji v. Harvey (1922)Document9 pages1.1. Shioji v. Harvey (1922)guerreroalexdanielleNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 18940 Shioji V HarveyDocument1 pageG.R. No. 18940 Shioji V HarveyFrances Ann TevesNo ratings yet

- Shioji v. Harvey, G.R. No. 18940, April 27, 1922Document2 pagesShioji v. Harvey, G.R. No. 18940, April 27, 1922I took her to my penthouse and i freaked itNo ratings yet

- Jimenez Vs Jimenez & Quezon City Register of Deeds, G.R. No. 228011, February 10, 2021Document2 pagesJimenez Vs Jimenez & Quezon City Register of Deeds, G.R. No. 228011, February 10, 2021Gi NoNo ratings yet

- 621 SCRA 511, A.M. Mo. P-08-2535, June 23, 2010Document35 pages621 SCRA 511, A.M. Mo. P-08-2535, June 23, 2010Gi NoNo ratings yet

- 862 SCRA 1, G.R. No. 211273, April 18, 2018Document73 pages862 SCRA 1, G.R. No. 211273, April 18, 2018Gi NoNo ratings yet

- Justice Mario Lopez, Natl Power Corp Vs Benguet Electric Cooperative, G.R. No. 218378, June 14, 2021 - Unjust EnrichmentDocument3 pagesJustice Mario Lopez, Natl Power Corp Vs Benguet Electric Cooperative, G.R. No. 218378, June 14, 2021 - Unjust EnrichmentGi NoNo ratings yet

- 546 Domino vs. Commission On Elections: Supreme Court Reports AnnotatedDocument41 pages546 Domino vs. Commission On Elections: Supreme Court Reports AnnotatedGi NoNo ratings yet

- Read ThisDocument27 pagesRead ThisGi NoNo ratings yet

- Bacabac Vs NYK-FIL Ship Management, G.R. No. 228550, July 28, 2021Document3 pagesBacabac Vs NYK-FIL Ship Management, G.R. No. 228550, July 28, 2021Gi NoNo ratings yet

- Alcantara 531 SCRA 446, G.R. No. 167746, August 28, 2007Document20 pagesAlcantara 531 SCRA 446, G.R. No. 167746, August 28, 2007Gi NoNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 200169. January 28, 2015. Rodolfo S. Aguilar, Petitioner, vs. Edna G. Siasat, RespondentDocument20 pagesG.R. No. 200169. January 28, 2015. Rodolfo S. Aguilar, Petitioner, vs. Edna G. Siasat, RespondentGi NoNo ratings yet

- 661 SCRA 589, G.R. No. 181704, December 6, 2011Document80 pages661 SCRA 589, G.R. No. 181704, December 6, 2011Gi NoNo ratings yet

- 696 SCRA 151, AM No. P082531, April 11, 2013Document18 pages696 SCRA 151, AM No. P082531, April 11, 2013Gi NoNo ratings yet

- Amonoy Vs GutierrezDocument11 pagesAmonoy Vs GutierrezMichelangelo TiuNo ratings yet

- Abing 497 SCRA 202, G.R. No. 146294, July 31, 2006Document11 pagesAbing 497 SCRA 202, G.R. No. 146294, July 31, 2006Gi NoNo ratings yet

- Ara and Garcia Vs Pizarro and Rossi, 817 SCRA 518, G.R. No. 187273, February 15, 2017Document37 pagesAra and Garcia Vs Pizarro and Rossi, 817 SCRA 518, G.R. No. 187273, February 15, 2017Gi NoNo ratings yet

- Dela Peña III, G.R. No. 216425, November 11, 2020Document22 pagesDela Peña III, G.R. No. 216425, November 11, 2020Gi NoNo ratings yet

- Abalos Vs People of The Philippines, 913 SCRA 395, G.R. No. 221836, August 14, 2019Document26 pagesAbalos Vs People of The Philippines, 913 SCRA 395, G.R. No. 221836, August 14, 2019Gi No100% (1)

- 3people of The Philippines Vs Jacinto, 645 SCRA 590, G.R. No. 182239, March 16, 2011Document41 pages3people of The Philippines Vs Jacinto, 645 SCRA 590, G.R. No. 182239, March 16, 2011Gi NoNo ratings yet

- 3engada Vs Court of Appeals, 404 SCRA 478, G.R. No. 140698, June 20, 2003Document12 pages3engada Vs Court of Appeals, 404 SCRA 478, G.R. No. 140698, June 20, 2003Gi NoNo ratings yet

- Almelor vs. Regional Trial Court of Las Pin - As City, Br. 254Document22 pagesAlmelor vs. Regional Trial Court of Las Pin - As City, Br. 254Queenie SabladaNo ratings yet

- Goods and Financial MarketsDocument32 pagesGoods and Financial MarketsmNo ratings yet

- SET 4. Data Interpretation Sets: Medium QuestionDocument9 pagesSET 4. Data Interpretation Sets: Medium QuestionSandeep PanjwaniNo ratings yet

- Pratibimb Introductory PagesDocument7 pagesPratibimb Introductory PagesSaurabh TrivediNo ratings yet

- Weight Reduction of Planetary Gearbox Pedestal Using Finite Element AnalysisDocument4 pagesWeight Reduction of Planetary Gearbox Pedestal Using Finite Element AnalysisPrabhakar PurushothamanNo ratings yet

- Exam 1 SolutionsDocument4 pagesExam 1 Solutionsgebretadios gebrekidanNo ratings yet

- Prove N Technol OGY: Unbeatable PerformanceDocument2 pagesProve N Technol OGY: Unbeatable PerformanceamarpathyNo ratings yet

- Test Bank Financial Accounting and Reporting TheoryDocument58 pagesTest Bank Financial Accounting and Reporting TheoryAngelie De LeonNo ratings yet

- Stainless Steel Laser Fused Universal Beams and ColumnsDocument8 pagesStainless Steel Laser Fused Universal Beams and ColumnsDushyantha JayawardenaNo ratings yet

- UTC Fire & Security Corporation Et Al v. John Does 1-100Document9 pagesUTC Fire & Security Corporation Et Al v. John Does 1-100Kenan FarrellNo ratings yet

- 12 Entry 3 Reentry VisaDocument8 pages12 Entry 3 Reentry VisaAnh NguyễnNo ratings yet

- m2588-Hvm-11-h01-001!20!1, Painting Procedure Rev 1, Sent Code-BDocument13 pagesm2588-Hvm-11-h01-001!20!1, Painting Procedure Rev 1, Sent Code-Brajesh100% (1)

- MAM880 User ManualDocument89 pagesMAM880 User ManualPopín Firulín PinpinNo ratings yet

- Is Iso 10079 2 1999Document20 pagesIs Iso 10079 2 1999Hemant SharmaNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Cryptocurrency AdoptionDocument13 pagesFactors Influencing Cryptocurrency AdoptionSeffaNo ratings yet

- Roof Gutter Items CalculationDocument2 pagesRoof Gutter Items Calculationwabule lydiaNo ratings yet

- 4D Seismic in A Heavy-Oil, Turbidite Reservoir Offshore BrazilDocument10 pages4D Seismic in A Heavy-Oil, Turbidite Reservoir Offshore BrazilVidho TomodachiNo ratings yet

- Alcatel-Lucent 7510 Media Gateway: Multiservice Media Networking Key FeaturesDocument4 pagesAlcatel-Lucent 7510 Media Gateway: Multiservice Media Networking Key FeaturesRobison Meirelles juniorNo ratings yet

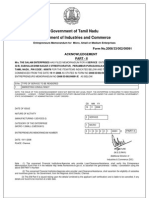

- Government of Tamil Nadu Department of Industries and CommerceDocument6 pagesGovernment of Tamil Nadu Department of Industries and Commercesalam20064909100% (3)

- ES9-62 Ingestive Cleaning PDocument9 pagesES9-62 Ingestive Cleaning PIfran Sierra100% (1)

- Steps in Writing Report (Advocacy)Document19 pagesSteps in Writing Report (Advocacy)RochelleNo ratings yet

- Astm F1544-2015Document9 pagesAstm F1544-2015JJGM120No ratings yet

- Ikoku Federal Educ CollegeDocument14 pagesIkoku Federal Educ CollegeYebekal MegefatNo ratings yet

- Itc LTDDocument56 pagesItc LTDRakesh Kolasani Naidu100% (1)

- Kemper FlowControl PDFDocument16 pagesKemper FlowControl PDFkhambhatNo ratings yet

- Profit Sharing ASSIGNMENTDocument4 pagesProfit Sharing ASSIGNMENTRoldan AzueloNo ratings yet

- Report of InternshipDocument31 pagesReport of InternshipHarshit GuptaNo ratings yet

- Optimization of Aniline Blue ProcessDocument6 pagesOptimization of Aniline Blue ProcessAditya ShrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Asic Design Cadence DR D Gracia Nirmala RaniDocument291 pagesAsic Design Cadence DR D Gracia Nirmala RaniAdline RiniNo ratings yet