Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Washingtonquarterly

Uploaded by

Jorge QuijanoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Washingtonquarterly

Uploaded by

Jorge QuijanoCopyright:

Available Formats

Arie P.

de Geus

The Living Company:

A Recipe for Success

in the New Economy

W hat distinguishing features characterize the New Economy? Is

it a mere wave of new technology, or should we look deeper? Does it

threaten only the weak and the meek? Or have the basic conditions to

achieve long-term business success changed dramatically?

In the early 1980s, several large companies began to worry about the

“post-industrial society.” Would they have a place in this new society?

Would economic growth occur in services, or in their bread-and-butter in-

dustrial products as well? In those days, these questions translated as a

vague feeling of unease—nothing more serious.

Since then, the words “post-industrial society” have gone somewhat out

of fashion. Today’s headlines announce that we live in an idea-driven world:

We have moved into the “Information Age” and entered the “Knowledge

Society.” These headlines remove a little of the unease. They somehow sug-

gest that the worst that is happening is a passing of a new wave of technol-

ogy. It makes the problem, if there is one, sound slightly less dramatic.

Nothing that should worry a well-established, solid business. Any company

more than 100 years old has experience in absorbing new technologies. The

internal combustion engine replaced horses, electricity replaced steam.

Technology changes spell dangerous times, but they do not lead to rephras-

ing the basic questions of business.

So, we must see behind the feeling of unease and explore the distinguish-

ing characteristics of the New Economy. In doing so, I suggest using the lan-

guage of economics. It may help us to discover if there is, indeed, a New

Arie de Geus, a former executive at the Royal Dutch/Shell Group, is now a visiting

fellow at London Business School. His articles have been published by the Harvard

Business Review and the Royal Society of Arts, London; he also wrote a book, The

Living Company (Harvard Business School Press, 1997).

Copyright © 1997 by The Center for Strategic and International Studies and the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Washington Quarterly • 21:1 pp. 197–205.

T HE WASHINGTON QUARTERLY ■ WINTER 1998 197

| Arie P. de Geus

Economy and, if so, whether its characteristics raise important questions

about the sources and the nature of success in business.

The science of economics describes the production of goods and services

(in other words, what most companies do) as a matter of combining three

production factors: natural resources, capital, and labor. The science of eco-

nomics does not say in most text books that, over time, these three produc-

tion factors did not have equal weight in this process of producing goods

and services. On this point, however, historians can greatly enrich the lan-

guage of the economists.

In the primitive Western world of a 1,000 years ago, humanity produced

its material wealth in a way that considered land and natural resources the

most important production factor. The dominance of land in producing

goods to sustain the population had highly visible consequences in early me-

dieval society: Those who had land were rich and powerful, and those who

did not were poor.

Then, starting some 500 years ago, people began gradually to add more

and more capital to this process of producing goods and services. Historians

like Simon Schama and Fernand Braudel de-

scribe in vivid detail what happened toward

the end of the Middle Ages in regions like

Supply of capital has Northern Italy and in Flanders.1 In those soci-

begun to exceed eties, poor though they were, production had

begun to exceed the immediate needs for con-

demand.

sumption. A modest portion of the population

began to accumulate savings which then, sur-

prisingly perhaps, found its way into produc-

tive processes, rather than into the lifestyle of

the ruling, land-based elite. We all know the results: Ships became bigger,

voyages longer, and mines deeper, and machines were added to the laborers

in the textile ateliers that began to replace the workshop of the medieval

tradesman.

This shift in the mix of production factors paralleled a quantum jump in

technology. Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press made pos-

sible a manifold increase in the speed and precision of the transmission of

human knowledge, which in turn had spectacular results in economic terms.

Both this new technology and the introduction of more capital to natural

resources greatly increased output. Not surprisingly, demand for capital in-

creased quickly and exceeded available savings. Capital became the scarce

production factor and, at the same time, the factor most critical for success

in the production of goods and services. Capital began to command the

maximum remuneration. That had consequences in society as a whole:

198 T HE WASHINGTON Q UARTERLY ■ WINTER 1998

The New Economy |

Those who had capital were rich and powerful, and those who had not were

poor. The Capitalist Era had begun.

The rise of capital as the critical production factor also gave birth to the

modern commercial company. The people who had access to this scarce and

critical production factor became the founders and the leaders of these com-

panies. As leaders, their top managerial priority became the optimization of

capital, meaning making the maximum use of it to remain competitive and

assuring the greatest return—the maximization of its remuneration—to

maintain access to it.

This situation lasted some 500 years and, in essence, still existed when I

was a student in the years immediately after World War II. But, from then

on, the world entered a period of unsurpassed capital accumulation. Institu-

tions and banks built up a financial resilience unknown until then. Indi-

viduals in many parts of the world began to accumulate savings and

investments. Technology increased the velocity with which money circu-

lated through society.

Now, 50 years later, capital is no longer scarce. For that same reason, it is

no longer critical for success in the production of goods and services. Supply

of capital has begun to exceed demand. Banks actively compete to give es-

tablished businesses all the capital they want and offer more money—

through credit cards—than most people could ever repay. Governments

found trillions of dollars to finance their spend-happy ways without raising

the price they had to pay much more than 1 percent or 2 percent above real

interest rates.

By the 1980s, the world’s financial resilience had become so great that

several shocks and capital-destroying events that, each, would have pro-

duced the 1929 depression, passed without plunging the system into a crisis.

Just think about the 1982 Mexico crisis, the 1986 oil price collapse, and the

October 1987 crash of the New York Stock Exchange. The Capitalist Era

had finished!

With capital easily available, in the language of the economists, the criti-

cal production factor has shifted to people. But it did not shift simply to “la-

bor.” Instead, knowledge displaced capital as the scarce production

factor—the key to commercial success. That has consequences in society as

a whole: Those who have access to knowledge and know how to use it will

be the New Rich, and those who have not will be the New Poor.

We have not yet digested the real meaning of these consequences. Soci-

ety continues to speak of its Poor in terms of the Capitalist Era: unem-

ployed, jobless, poor in money. It still tries to resolve the societal tensions of

this inequality in terms of the solution developed in the nineteenth century

to deal with the tensions of the capitalist world: by redistributing money.

THE W ASHINGTON QUARTERLY ■ W INTER 1998 199

| Arie P. de Geus

And at the same time that Japanese car companies increase the recruitment

threshold for assembly-line workers to 16 years of formal education, the

West wonders why its social safety net cannot return a whole layer of the

population back into the production process.

Until we develop a new language in which to think about the realities of

our present society, we will not be able to deal with its tensions. Redistribut-

ing money no longer provides a complete answer. Nothing is easier and, at

the same time, nothing is more difficult than to redistribute the scarce pro-

duction factor of today: Knowledge. It is easy and cheap to give, but its re-

distribution requires not so much the act of giving, as the willingness and

capability to receive it.

Also in business, the shift to knowledge has monumental consequences.

As was the case 500 years ago, a quantum jump in technology has accompa-

nied the shift in the critical production factor. The megatechnology based

on the microchip has revolutionized the production of goods and services.

In business, in the same way as in society at large, we see new winners and

new losers. During these last 50 years of transition, the new winners in the

business world became visible in the rise of capital-poor but brain-rich com-

panies and partnerships: international auditing firms, law firms, advertising

agencies, and the news media. Lately, the explosively growing software and

information technology (IT) companies have eclipsed even these firms.

Managers cannot run these brain-rich companies in the old capital-ori-

ented style. They have had to change their priorities. Instead of running

their companies to optimize capital, they must find a way to optimize

people. Their companies have hardly any capital. Their people carry the

knowledge and, therefore, the source of competitive advantage. Today even

the old type of capital-rich company, such as oil and steel firms, need much

more knowledge embedded in their actions and in their products than they

did some 20 years ago.

So, the science of economics does help us to see some of the distinguish-

ing characteristics of the post-industrial society. Unfortunately, economics is

less helpful in examining the question, “How does one make a business suc-

cessful in this new world?” Where economists talk about business, their lan-

guage is stuck in the Capitalist–Industrial world of a half-century ago.

Witness the description of what one might call the “economic company,”

which I learned 50 years ago and that today’s business school student can

still recognize:

The production of goods and services takes place in organizations which

are called companies. They produce goods for which other people are pre-

pared to pay a price. Companies produce those goods by trying to find the

optimum combination of the three production factors: labor, capital, and

land. These three are substitutable, meaning for example that capital can

200 T HE WASHINGTON Q UARTERLY ■ WINTER 1998

The New Economy |

replace labor. The optimum combination of the production factors is the

one at which the company produces goods and services at minimum costs

to be sold at maximum price for the maximization of profits.3

This description, which dates from the Capitalist period, ignores the eco-

nomic realities of today. Capital is no longer scarce, nor is it the critical

source of commercial success. Yet, this description still defines “success in

business” as the maximization of profits and, by implication, says that man-

agers’ number one priority should be to maximize shareholder value. Under-

standably pleasant as this definition is for shareholders, it also has an

undeniable appeal for managers. The economic definition has great clarity,

because, basically, it says that the Economic Company is

• rational—it aims to maximize profits by minimizing costs;

• calculable—you can express this rational in figures; and

• controllable—the interchangeability of labor and capital creates the illu-

sion of managerial control, at the same time as it obeys the tenet of cor-

porate success (that is, maximum profits).

Attractive though it may seem, the economic definition points toward a

dangerous course to sail. The modern brain-rich company is in the first

place a community of people that, to succeed, must maximize its available

brain capacity. Creating a community and, then, creating the conditions

that will make maximum use of the combined intelligence of the community

members, is neither easy to control nor calcu-

lable (certainly not a priori and not in the

short run), and it is not rational in the same

sense as is maximizing profits. Today’s top

With the shift in the critical production business priority

factor from capital to knowledge comes a

is shaping the

shift in the priorities of management. From

making the maximum use of capital and as- work community.

suring the greatest return on capital, the top

priority now turns to shaping the work com-

munity and creating the conditions for the

maximum use of the available brain capacity.

To understand how that works, biology, especially evolutionary biology,

provides us with a more effective language than economics. Research by

three American evolutionary biologists is particularly illuminating. In the

course of their work on the (different) speeds of evolution between species,

they began to suspect that certain species were better at “learning to de-

velop a new skill to exploit the environment in a new way” than were com-

peting species. 4 That is a neat way to express the relationship between

“learning” and being successful in a competitive world. It is, surely, not dis-

similar from the way that, for example, Microsoft would define its competi-

THE W ASHINGTON QUARTERLY ■ W INTER 1998 201

| Arie P. de Geus

tive behavior. So, how do biological species develop these superior competi-

tive abilities to improve their chances of survival and further evolution?

According to Allan Wilson and his two colleagues, accelerated evolution

occurs in species with numerous mobile individuals, some of which can in-

novate. But the species as a whole must have an effective way to propagate

those innovations. When these three conditions are present, the scientists’

hypothesis predicts accelerated learning in the species as a whole, meaning

better and faster adaptation to fundamental changes in the environment. To

find evidence for their hypothesis, they turned to a well-documented case in

the United Kingdom.

In the nineteenth century, the British dairy monopoly introduced a coun-

trywide distribution system that deposited milk bottles at the door of every

house. Originally, these bottles had no seal. Two species of English garden

birds, titmice and red robins, learned to feed from the rich cream in the top

of these open bottles. In between the two

world wars, the dairy system put aluminum

A lasting work seals on the bottles, closing the access to this

new food source. Many accounts report that

community requires by the 1950s the whole titmice population,

its management to estimated at some 1 million birds, from the

think in terms of North of Scotland to Land’s End, had learned

how to pierce the aluminum tops and to re-

generations. gain access to the rich cream. In contrast,

even now, red robins, as a species, have not

regained access and remain at a competitive

disadvantage. Individual red robins do occa-

sionally learn how to pierce the seals, but the species as a whole has not

gained from their knowledge.

But why? Both species have numerous mobile individuals, of which some

have the capacity for innovation. The difference in “institutional” learning,

as opposed to individual learning, between the species must lie in different

systems of social propagation. And, indeed, a fundamental difference does

exist between titmice and red robins. The latter are territorial birds. The

males divide the garden in distinct territories and although red robins have

the same rich gamma of communication as the titmice, they use it primarily

in an antagonistic manner across the boundaries of their territories. In

short, they tell the other members of their species, “Keep out of here!” This

is not unprecedented in the corporate world, where many of us have experi-

ence with companies that have divided their corporate garden into spheres

of influence. The amount of learning in the board rooms of those companies

quite often compares with that of the red robins.

202 T HE WASHINGTON Q UARTERLY ■ WINTER 1998

The New Economy |

The lessons we can draw from Wilson’s research are basic: Birds that

flock, learn faster.

The implications of that conclusion for those managements that set out

to organize their company as a community of people are quite evident. It

would certainly be interesting to begin to think in what way Wilson’s three

conditions—mobility, innovation, and propagation—can be translated by

management into a corporate community. But before we do that in more de-

tail, we should examine some other conditions of a successful community

which are inherent in the biological approach.

As a group, titmice are recognizable to themselves and to others; they

have similar patterns of behavior and they try to survive from generation to

generation over as long a period as is possible. To put that in more abstract

words: Species strive for continuity, show cohesion, and have a sense of

identity. Research done in the Royal Dutch/Shell group of companies and,

more recently, a study by Stanford professors James Collins and Jerry Porras,

give strong evidence that companies that have been successful in terms of

growth and longevity demonstrate similar characteristics. 6 What do we

mean by “continuity” and what should managers do to build that trait into

their work community?

A long-lasting, continuous work community requires its management to

think in terms of generations. The company should still be there, and thriv-

ing, when its founders have died. The company becomes like a river. A

river—of which the water drops that form it continuously change—is itself a

constant feature in the landscape. New drops join the river all the time and

run its length, regularly moving position until they end up in the sea. A

river is a continuous community with a changing population that is con-

stantly mobile.

The image of the river begins to give us clues of what needs to be done to

create a corporate work community. Management will have to organize the

continuous entry into and exit from the corporate river. The entry—what

we normally call “recruitment”—is how new members join the work com-

munity. We test whether potential members have the abilities to function in

this community; we decide whether they have sufficient potential to flow

the length of the river; and we ascertain whether they exhibit a sufficient

compatibility of values to maintain the cohesion of the community. At the

same time, strict exit rules govern the regular outflow of the river. Manage-

ment should not dam succeeding generations behind a wall of individuals

who consider themselves irreplaceable. Thinking in generations is good for

humility—leadership becomes stewardship.

Recruitment to create a community differs greatly from recruitment in an

Economic Company. In the latter it involves finding the people to fit the as-

THE W ASHINGTON QUARTERLY ■ W INTER 1998 203

| Arie P. de Geus

set base of the company. This view is strongly embedded in the English lan-

guage. We speak of labor in terms of “cogs” or “hands.” People are but the

hands to operate the machine. We decide how many to recruit based on the

needed capacity—if the demand for our products exceeds the company’s ca-

pacity to produce, we add machines and labor. This depersonalizes recruit-

ment to finding “skills,” not admitting “members.” The underlying contract

between the company and the hands that bring the skills is one of “deliver-

ing the skill against the payment of a remuneration.” Money serves as the

dominant element in the labor contract.

In contrast, in a “river company,” recruitment aims at the creation of

a corporate work community. Remuneration is the hygiene factor that A.

H. Maslow described some 30 years ago. The underlying contract be-

tween company and member is based on a well-understood mutual self-

interest of both parties: The company undertakes to develop the new

member’s ultimate potential, because both parties know that the devel-

opment of the members’ potential creates

the corporate potential.

H elping individuals Clearly, setting out to create continuity—

thinking in generations—already produces a

develop their full strong element of mobility. Fulfilling the con-

potential elevates ditions of the underlying contract—“helping

the company’s the individual to develop to the ultimate of

innovative potential. his or her potential”—elevates the innovative

potential of the company at the same time as

it improves the system of social propagation in

the community. Knowledge travels with

people, not on paper! Corporate training and

management development have proven track records in this respect. And so

have systems of job rotation and career development—if management sees

them as a priority and applies them actively.

None of these techniques is new. What is new is the growing understand-

ing that in the modern world these techniques are the way into and the ba-

sic conditions for a company’s long-term success. Of course, a company may

not want to have long-term success. Next quarter’s profit figure may be set,

by the company or by outsiders, as the company’s top priority. And that is

fine, but there is no free lunch.

Because such a policy forces the company to operate “skills-for-money”

contracts, which lower loyalty and mutual trust, the result is less commonal-

ity of goals and reduced levels of trust, which then require a management

style based on stronger hierarchical controls. Stronger controls reduce the

space for innovation and lead to lower learning abilities of the company as a

204 T HE WASHINGTON Q UARTERLY ■ WINTER 1998

The New Economy |

whole. Lower levels of learning in the post-industrial society reduce a

company’s life expectancy in a world in which success depends on the abil-

ity to maximize the use of the available brain capacity.

On the other hand, creating the conditions of mobility, the space for in-

novation, and an effective system of social propagation—recruiting with co-

hesion and continuity in mind and developing the ultimate potential of the

community’s members-creates the conditions for faster institutional learn-

ing in the New Economy in which success depends on that learning.

Every management team has a choice.

Notes

1. See Simon Schama, The Embarrassment of Riches (Berkeley and Los Angeles: Uni-

versity of California Press, 1988), and Fernand Braudel, The Wheels of Commerce,

vol. 2 of Civilization & Capitalism 15th–18th Century (Berkeley and Los Angeles:

University of California Press, 1992).

2. Michael L. Rothschild, Bionomics (London: Futura Publications, 1992), pp. 8–10.

3. Taken from Wilhelm Röpke, Die Lehre von der Wirtschaft (The Handbook of Eco-

nomic Science), (Zürich: Eugen Rentsch Verlag, 1946).

4. Jeff S. Wyles, Joseph G. Kimbel, and Allan C. Wilson, “Birds, Behavior and Ana-

tomical Evolution,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, (Washington:

NAS Press, July 1993).

5. See A. P. de Geus, The Living Company (Boston: Harvard Business School Press,

1997).

6. James C. Collins and Jerry I. Porras, Built to Last (New York: Harper-Collins, 1994).

THE W ASHINGTON QUARTERLY ■ W INTER 1998 205

You might also like

- The Great Reset: How New Ways of Living and Working Drive Post-Crash ProsperityFrom EverandThe Great Reset: How New Ways of Living and Working Drive Post-Crash ProsperityNo ratings yet

- Carlota Perez Technology-Development 1Document7 pagesCarlota Perez Technology-Development 1Dr. Ir. R. Didin Kusdian, MT.No ratings yet

- Because People Matter: Building an Economy that Works for EveryoneFrom EverandBecause People Matter: Building an Economy that Works for EveryoneNo ratings yet

- 46 Clase Magistral Phelps EngDocument10 pages46 Clase Magistral Phelps EngSophie- ChanNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Society: Making Business, Government and Money Work AgainFrom EverandSustainable Society: Making Business, Government and Money Work AgainNo ratings yet

- Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy that Works for Progress, People and PlanetFrom EverandStakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy that Works for Progress, People and PlanetRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (3)

- Financial Fiasco: How America's Infatuation With Homeownership and Easy Money Created the Financial CrisisFrom EverandFinancial Fiasco: How America's Infatuation With Homeownership and Easy Money Created the Financial CrisisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Why Things Are Going to Get Worse - And Why We Should Be GladFrom EverandWhy Things Are Going to Get Worse - And Why We Should Be GladNo ratings yet

- Has Western Capitalism FailedDocument6 pagesHas Western Capitalism Failedapi-98469116No ratings yet

- Short Circuit: Strengthening Local Economies for Security in an Unstable WorldFrom EverandShort Circuit: Strengthening Local Economies for Security in an Unstable WorldRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- The Land of Enterprise: A Business History of the United StatesFrom EverandThe Land of Enterprise: A Business History of the United StatesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Boulevard of Broken Dreams: Why Public Efforts to Boost Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital Have Failed--and What to Do about ItFrom EverandBoulevard of Broken Dreams: Why Public Efforts to Boost Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital Have Failed--and What to Do about ItRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Managing in the Next Society: Lessons from the Renown Thinker and Writer on Corporate ManagementFrom EverandManaging in the Next Society: Lessons from the Renown Thinker and Writer on Corporate ManagementRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Macroeconomics For A Modern Economy: Economic Contrasts Between The Two SystemsDocument19 pagesMacroeconomics For A Modern Economy: Economic Contrasts Between The Two SystemsIyud Wahyudin Al SundanieNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Business in America's EconomyDocument4 pagesEvolution of Business in America's Economymarjuka puffpuffNo ratings yet

- Meeting Globalization's Challenges: Policies to Make Trade Work for AllFrom EverandMeeting Globalization's Challenges: Policies to Make Trade Work for AllNo ratings yet

- The New Entrepreneurs: Building a Green Economy for the FutureFrom EverandThe New Entrepreneurs: Building a Green Economy for the FutureRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- To the Man with a Hammer: Augmenting the Policymaker's Toolbox for a Complex WorldFrom EverandTo the Man with a Hammer: Augmenting the Policymaker's Toolbox for a Complex WorldNo ratings yet

- Mass Flourishing: How Grassroots Innovation Created Jobs, Challenge, and ChangeFrom EverandMass Flourishing: How Grassroots Innovation Created Jobs, Challenge, and ChangeRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (9)

- Chapter 1: Corporate ChallengesDocument22 pagesChapter 1: Corporate ChallengesRoselynne GatbontonNo ratings yet

- Debtonator: How Debt Favours the Few and Equity Can Work For All of UsFrom EverandDebtonator: How Debt Favours the Few and Equity Can Work For All of UsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- The Invention of Enterprise: Entrepreneurship from Ancient Mesopotamia to Modern TimesFrom EverandThe Invention of Enterprise: Entrepreneurship from Ancient Mesopotamia to Modern TimesNo ratings yet

- Fields, Factories, and Workshops: Industry Combined with Agriculture and Brain Work with Manual WorkFrom EverandFields, Factories, and Workshops: Industry Combined with Agriculture and Brain Work with Manual WorkNo ratings yet

- The Temp Economy: From Kelly Girls to Permatemps in Postwar AmericaFrom EverandThe Temp Economy: From Kelly Girls to Permatemps in Postwar AmericaNo ratings yet

- The Next Convergence: The Future of Economic Growth in a Multispeed WorldFrom EverandThe Next Convergence: The Future of Economic Growth in a Multispeed WorldRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Factorsof Production EcoDocument17 pagesFactorsof Production Ecopeterson alvarezNo ratings yet

- Capitalism and Its Economics: A Critical HistoryFrom EverandCapitalism and Its Economics: A Critical HistoryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- End Of The Road: Political-Economic Catastrophe From Fiat, Debt, Inflation Targeting and InequalityFrom EverandEnd Of The Road: Political-Economic Catastrophe From Fiat, Debt, Inflation Targeting and InequalityNo ratings yet

- What to Do When the Bubble Pops: Personal and Business Strategies For The Coming Economic WinterFrom EverandWhat to Do When the Bubble Pops: Personal and Business Strategies For The Coming Economic WinterRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Bad Times - An Essay on the Present Depression of Trade: Tracing It to Its Sources in Enormous Foreign Loans, Excessive War Expenditure, the Increase of Speculation and of Millionaires, and the Depopulation of the Rural Districts; With Suggested RemediesFrom EverandBad Times - An Essay on the Present Depression of Trade: Tracing It to Its Sources in Enormous Foreign Loans, Excessive War Expenditure, the Increase of Speculation and of Millionaires, and the Depopulation of the Rural Districts; With Suggested RemediesNo ratings yet

- Book Review: Capital in the Twenty-First Century by Thomas Piketty: Understand inequality in the modern worldFrom EverandBook Review: Capital in the Twenty-First Century by Thomas Piketty: Understand inequality in the modern worldNo ratings yet

- The New Zealand Land & Food Annual 2016: Volume 1From EverandThe New Zealand Land & Food Annual 2016: Volume 1No ratings yet

- Globalization Debate: Benefits and InequalitiesDocument6 pagesGlobalization Debate: Benefits and InequalitiesAnthony BechaydaNo ratings yet

- Consumerless Economy: Crisis Created a Million of Millionaires and Can Make You Very Rich Too.From EverandConsumerless Economy: Crisis Created a Million of Millionaires and Can Make You Very Rich Too.No ratings yet

- Reclaiming the European Street: Speeches on Europe and the European Union, 2016-20From EverandReclaiming the European Street: Speeches on Europe and the European Union, 2016-20No ratings yet

- John Kenneth Galbraith: Selected Summaries: SELECTED SUMMARIESFrom EverandJohn Kenneth Galbraith: Selected Summaries: SELECTED SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- 19 Biggest Pros and Cons of Industrial RevolutionDocument10 pages19 Biggest Pros and Cons of Industrial RevolutionSTEPHEN EDWARD VILLANUEVANo ratings yet

- Pilzer Isagenix Yb1.7Document3 pagesPilzer Isagenix Yb1.7thikoNo ratings yet

- The New Pioneers: Sustainable business success through social innovation and social entrepreneurshipFrom EverandThe New Pioneers: Sustainable business success through social innovation and social entrepreneurshipNo ratings yet

- User Manual of DS-8100-S DVR (V2.0.1)Document97 pagesUser Manual of DS-8100-S DVR (V2.0.1)Carlos Rojas ZapataNo ratings yet

- Laidz Lwpuk: / Contact InformationDocument4 pagesLaidz Lwpuk: / Contact InformationAbirami PriyadharsiniNo ratings yet

- Erosion-Corrosion Resistant Ceramic CoatingDocument2 pagesErosion-Corrosion Resistant Ceramic CoatingrobertomaleoNo ratings yet

- AVR520 Service ManualDocument160 pagesAVR520 Service ManualtlehotskyNo ratings yet

- Compro StarlinkDocument20 pagesCompro Starlinkjohan artajayaNo ratings yet

- Pressure Data Logger PDFDocument2 pagesPressure Data Logger PDFMuhammad Akbar WalennaNo ratings yet

- Gujranwala 3G OMO Drive Test ReportDocument20 pagesGujranwala 3G OMO Drive Test Reportzahir shahNo ratings yet

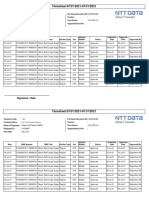

- Time Sheet - JulyDocument3 pagesTime Sheet - JulyraghuNo ratings yet

- HeatEnginesVol 2 Chapter 7 RS PDFDocument29 pagesHeatEnginesVol 2 Chapter 7 RS PDFMahesh Babu TalupulaNo ratings yet

- Full Text-2D Electromagnetic Transient and Thermal Modeling of A Three Phase Power Transformer - 1Document5 pagesFull Text-2D Electromagnetic Transient and Thermal Modeling of A Three Phase Power Transformer - 1NituNo ratings yet

- Acceptance Criteria For Damaged PFP Info Sheet 12-2007Document9 pagesAcceptance Criteria For Damaged PFP Info Sheet 12-2007Richard HollidayNo ratings yet

- A307-14 Standard Specification For Carbon Steel Bolts, Studs, and Threaded Rod 60000 PSI Tensile StrengthDocument6 pagesA307-14 Standard Specification For Carbon Steel Bolts, Studs, and Threaded Rod 60000 PSI Tensile Strengthmasv792512No ratings yet

- Archival Description Standards - Concepts, Principles, and MethodologiesDocument10 pagesArchival Description Standards - Concepts, Principles, and MethodologiespoueyNo ratings yet

- Lukjanenko LabyrinthDocument198 pagesLukjanenko LabyrinthStDeepBlueNo ratings yet

- Erosion and Erosion-Corrosion of Metals: A.V. LevyDocument12 pagesErosion and Erosion-Corrosion of Metals: A.V. LevyPritha GuptaNo ratings yet

- HSBCDocument21 pagesHSBCHarsha SanapNo ratings yet

- Reparatii DrujbaDocument279 pagesReparatii Drujbaest_nuNo ratings yet

- E-Business Assignment-I: Chintan Shah 1 2 6 Mba Tech. It Trim X, Mumbai Campus 1 7 AugustDocument11 pagesE-Business Assignment-I: Chintan Shah 1 2 6 Mba Tech. It Trim X, Mumbai Campus 1 7 AugustChintan ShahNo ratings yet

- Teatrocompleto07eche DjvuDocument1,082 pagesTeatrocompleto07eche DjvudenialmanNo ratings yet

- Nikon D200 Sensor CleaningDocument11 pagesNikon D200 Sensor CleaningDan Și Maria MierluțNo ratings yet

- Understanding Generator Power System StabilizerDocument12 pagesUnderstanding Generator Power System StabilizerRamakrishna100% (1)

- Samsung PN51F5500 Calibration ReportDocument2 pagesSamsung PN51F5500 Calibration Reportty_at_cnetNo ratings yet

- MM Met D19084 RP 012Document96 pagesMM Met D19084 RP 012Dass DassNo ratings yet

- Manual Ecograf Portabil WED 9618Document76 pagesManual Ecograf Portabil WED 9618dorian0887% (15)

- FlyweelDocument6 pagesFlyweelTalebNo ratings yet

- Survey Research: Maria Lucia BarronDocument46 pagesSurvey Research: Maria Lucia BarronWendy SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Op-3-65. Checklist For Jack-In-Pile Supervision: Work Instructions For EngineersDocument4 pagesOp-3-65. Checklist For Jack-In-Pile Supervision: Work Instructions For Engineersjinwook75No ratings yet

- Desain PCBDocument23 pagesDesain PCBAlvian LimNo ratings yet

- Bombas de Agua PaiDocument17 pagesBombas de Agua PaiEver Rivera50% (2)

- Nigeria National Id Card Report 2006Document63 pagesNigeria National Id Card Report 2006elrufaidotorgNo ratings yet