Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Association For Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve

Association For Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve

Uploaded by

Marcos TorresOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Association For Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve

Association For Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve

Uploaded by

Marcos TorresCopyright:

Available Formats

Engendering Russia's History: Women in Post-Emancipation Russia and the Soviet Union

Author(s): Barbara Alpern Engel

Reviewed work(s):

Source: Slavic Review, Vol. 51, No. 2 (Summer, 1992), pp. 309-321

Published by:

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2499534 .

Accessed: 09/01/2013 06:54

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve

and extend access to Slavic Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded on Wed, 9 Jan 2013 06:54:48 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Engendering Russia's History: Women in Post-

Emancipation Russia and the Soviet Union

Barbara Alpern Engel

The revival of the women's movement in the late 1960s sparked a

resurgence of interest in women in Russia and the Soviet Union. His-

torians then already had foundations on which to build such as S. S.

Shashkov's survey of the history of women in Russia' and Elena Li-

khacheva's monumental pre-revolutionary study of women's education

in Russia which extended beyond the limit of its title to explore the

birth and growth of the Russian women's movement.2

Historians and social scientists in the 1970s attempted to find

women omitted from previous accounts of Russian and Soviet history.

In 1978, Richard Stites published his monumental and pioneering study

that maps vast portions of the terrain that other scholars would later

explore in greater detail and from different perspectives.3 Some mem-

bers of this new generation of scholars, myself among them, were per-

sonally and politically as well as intellectually motivated. Feminism

encouraged women historians of Russia, as it encouraged historians of

the US and western Europe, to seek "our" past, to tell "herstory." To

correct the masculine bias of earlier accounts, we hunted through ar-

chives and published sources, looking for traces of women's experi-

ences, trying to hear women's hitherto silent voices. If we studied lit-

erate women, as most of us did, we pored over diaries, memoirs and

letters. To the usual questions of historians and social scientists, this

feminist cohort added new ones, questions concerning the power that

men exercised over women and its impact on women's ideas and ex-

periences. We questioned the nature and sources of patriarchal power

and asked how being female shaped a woman's choices and activities.

And even as we carefully gathered and sifted evidence, as professional

historians do, explicitly or not and in varying degrees, we often brought

our own experience as women and as subjected beings to the materials

we examined.4

I would like to thank Diana Greene for her advice and assistance in the preparation

of this essay.

1. S. S. Shashkov, Istoriia russkoizhenshchiny(St. Petersburg: 0. N. Popova, 1898).

2. Elena Likhacheva, Materialydlia istorii zhenskogoobrazovaniiav Rossii (St. Peters-

burg: Tip. M. M. Stasiulevicha, 1899-1901). Most early works in English, while useful

introductions to the past of Russia's women, often lacked both scholarly rigor and

scholarly apparatus. See, for example, Nina Selivanova, Russia's Women(New York: E.

P. Dutton & Co., 1923).

3. Richard Stites, The Women'sLiberationMovementin Russia: Feminism,Nihilism and

Bolshevism,1860-1930 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978).

4. In my introduction to Mothers and Daughters, I acknowledge the personal ele-

ment explicitly; so do the editors of a recent collection on Soviet women. See Barbara

Alpern Engel, Mothers and Daughters: Womenof the Intelligentsia in Nineteenth Century

Slavic Review 51, no. 2 (Summer 1992)

This content downloaded on Wed, 9 Jan 2013 06:54:48 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

310 Slavic Review

Whether or not scholars adopted a self-consciously feminist per-

spective, its content places much of this initial scholarship in "contri-

bution" history, to borrow Gerda Lerner's phrase. Such histories de-

scribe "women's contribution to, their status in and their oppression

by male-defined society."5 Partly because of the intrinsic importance

of those topics, but also because they left a relatively accessible paper

trail, they focus either on women of the intelligentsia or on the bol-

shevik attempt to liberate women after 1917.6 While such works re-

vealed hitherto unknown or neglected aspects of Russian women's ex-

periences, they primarily discussed only the educated, the articulate

and the radical; they told us almost nothing about the lives and ex-

periences of "ordinary" Russian women-lives which activist women

rejected and which revolutionaries aimed to transform. They also left

unchallenged the ways that historians have traditionally conceptual-

ized and periodized Russia's past.

More recently, the focus has broadened, the questions have grown

more multi-faceted and the methodologies more diverse. Evolution

and diversity were evident at a conference on "The History of Women

of the Russian Empire," held in Akron, Ohio in August 1988. Scholars

from England, the Soviet Union, Germany, Australia and the United

States contributed papers on a broad range of topics that offered new

perspectives on women's experience and on the role of gender in struc-

turing historical change. In 1991, selected articles from the conference

were published.7 Together with the scholarship that has appeared in

the last decade or so, the collection provides a basis for reassessing

Russia's past.

Russia (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1983); and Barbara Holland, "Intro-

duction," Soviet Sisterhood,ed. Barbara Holland (Bloomington: Indiana University Press,

1985).

5. On "contribution" history, see Gerda Lerner, "Placing Women in History: A

1975 Perspective," in Liberating Women'sHistory, ed. Bernice Carroll, (Urbana: Univer-

sity of Illinois Press, 1976), 358, 360. Works on Russian history that conform to this

characterization are to be found in the note that follows.

6. Jay Bergman, VeraZasulich (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1983) Vera

Broido, Apostles into Terrorists:Womenand the RevolutionaryMovement in the Russia of

AlexanderII (New York: Viking Press, 1977); Barbara Clements, BolshevikFeminist: The

Life of AleksandraKollontai (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1979); Barbara En-

gel and Clifford Rosenthal, eds., Five Sisters: WomenAgainst the Tsar (New York: Alfred

Knopf, 1975); Beatrice Farnsworth, AleksandraKollontai:Socialism,Feminismand the Bol-

shevik Revolution (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1980); Ann Hibner Koblitz, A

Convergenceof Lives:SofiaKovalevskaia:Scientist, Writer,Revolutionary(Boston: Birkhauser

Boston, Inc., 1983); Robert McNeal, Bride of the Revolution (Ann Arbor: University of

Michigan Press, 1972); Cathy Porter, Fathersand Daughters:Russian Womenin Revolution

(London: Virago, 1976); Gail Lapidus, Womenin Soviet Society:Equality,Developmentand

Social Change(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978). The pioneering collection

Womenin Russia, (ed. Dorothy Atkinson, Alexander Dallin and Gail Lapidus, [Stanford:

Stanford University Press, 1977]) contains essays that extend beyond these subjects, as

does The Family in Imperial Russia: New Lines of Historical Research (ed. David Ransel

[Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978]).

7. Barbara Clements, Barbara Engel and Christine Worobec, eds., Russia's Women:

Accommodation, Resistance,Transformation(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991).

This content downloaded on Wed, 9 Jan 2013 06:54:48 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Notes and Comments 311

This essay is an overview of the major themes in recent publications

and the fresh perspectives that they offer on the history of post-eman-

cipation Russia and the Soviet Union. I will treat only publications in

English.

Much recent work, mirroring larger developments in the field of

Russian history, treats the lives of lower class women. Scholars of

women have gone to the people, as did the intelligentsia that so many

of the first generation initially studied. And as was the case with the

intelligentsia, social and cultural differences have raised formidable

barriers to communication. Few working women and still fewer peas-

ant women left the kind of personal documents that allow historians

to trace the experience of educated women. Historians must therefore

rely heavily on the accounts of others. But the majority of ethnogra-

phers, physicians, lawyers, zemstvo statisticians, socialists of various

stripes and others who produced accounts of the lower class were for

the most part educated men who brought their own class, gender and

political biases to bear on the information they transmitted. While the

few primary sources written from a feminist perspective provide an

important counterbalance and corrective, they are of course no more

objectively "true" than the rest.8 Finally, in the field of social history,

as in every other field of Russian history, there is a persistent tendency

to assume that the masculine experience is the universal one. All of

this complicates the problem of interpretation and makes it difficult

to shift the focus to women.

Rose Glickman's ground-breaking study of the Russian factory

woman demonstrates some of the difficulties in shifting focus.9 Based

on prodigious research in published and archival sources, Glickman's

respectful treatment of the woman worker is aimed at revising Russian

labor history. On the one hand, it describes patriarchal tradition, the

confinement of women to unskilled and semiskilled labor and women's

contemptuous treatment by organized men as circumstances that re-

tarded women's ability to organize. On the other hand, it demonstrates

convincingly that women workers were nonetheless acquiring a sense

of their own self-worth and becoming more militant. Such an approach

effectively takes issue with the tendency of labor historians to dismiss

women workers as "backward" because of their failure to engage in

strikes or to join labor organizations to the same degree as men. How-

ever, it uncritically accepts such activities as the sole measure of "con-

sciousness" and does not ask whether women might have found other

forms of collective action or political expression more congenial. For

example, Glickman explores neither the ties between women workers

8. See, for example, Aleksandra Efimenko, Izsledovaniianarodnoi zhizni (Moscow:

V. I. Kasperov, 1884); Maria Gorbunova's study of peasant women's crafts, published

as Sbornikstatisticheskikhsvedenii po moskovskoigubernii, t. 7, vyp. 4 (Moscow: Izd. mos-

kovskago gubernskago zemstva, 1882) and the numerous articles by Maria Pokrovskaia.

9. Rose Glickman, The Russian Factory Woman: Workplaceand Society, 1880-1914

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984).

This content downloaded on Wed, 9 Jan 2013 06:54:48 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

312 Slavic Review

nor the workplace culture that historians of women in other times and

places have found to be important elements in women's resistance.10

Indeed, one of her contentions is that Russian women had no such

ties, that unmarried women especially were singularly isolated.11 Given

the importance of zemliak and kin in facilitating women's migration

from villages, such isolation seems unlikely.

In her book and in recent articles, Glickman addresses the deploy-

ment of power on a personal level: they present stark and unrelenting

pictures of peasant patriarchy and stress the extreme oppression of

the peasant woman in addition to her prodigious burden of work in

the field and the household. Rural oppression included women's lack

of access to land in their own right, their absence from village self-

government (the skhod) and their subordination in the family.12 Judith

Pallot's work on women and kustarsupports this perspective by arguing

that, while women's participation in household industry may have ex-

panded their horizons and enabled them to contribute to household

economies, it failed to alter women's subordinate status in household

and village.13

Other research on peasant women presents a rather different pic-

ture and some of it suggests alternative modes of power and social

standing among Russian peasants. Christine Worobec shows that

women had property rights to their dowries and to goods purchased

with brideprice, and that as widows they could gain access to com-

munal lands.14 Based on her research in volost' court records, Beatrice

Farnsworth asserts that the peasant daughter-in-law, the least powerful

member of the household, actually enjoyed considerable status and

rights."5As David Ransel notes in his account of the Russian foundling

system, many peasant women behaved more like entrepreneurs than

passive victims.16 By drawing on ethnographic and zemstvo materials

10. For a discussion of recent scholarship on women's work culture, see Sandra

Morgen, "Beyond the Double Day: Work and Family in Working-Class Women's Lives,"

Feminist Studies 16, no. 1 (Spring 1990): 53-67.

11. On the basis of very different evidence, Anne Bobroff draws the same con-

clusion. See "Russian Working Women: Sexuality in Bonding Patterns and the Politics

of Daily Life," in Powers of Desire: The Politics of Sexuality, eds. Ann Snitow, Christine

Stansell and Sharon Thompson, (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1983), 206-27.

12. Rose Glickman, "Women and the Peasant Commune," in Land Communeand

Peasant Communityin Russia: CommunalFormsin Imperialand EarlySovietSociety,ed. Roger

Bartlett (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1990), 321-38; and "The Peasant Woman as

Healer" in Russia's Women,163-85.

13. Judith Pallot, "Women's Domestic Industries in Moscow Province, 1880-1900,"

in Russia's Women,163-85.

14. Christine Worobec, "Customary Law and Property Devolution among Russian

Peasants in the 1870s," Canadian Slavonic Papers XXVI, nos. 2 and 3 Uune-September

1984): 220-34.

15. Beatrice Farnsworth, "The Litigious Daughter-in-Law: Family Relations in Ru-

ral Russia in the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century," Slavic Review 45, no. 1

(Spring 1986): 49-64.

16. David Ransel, "Abandonment and Fosterage of Unwanted Children: The

Women of the Foundling System," in The Family in ImperialRussia, 189-217.

This content downloaded on Wed, 9 Jan 2013 06:54:48 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Notes and Comments 313

and by examining demographic patterns, I have demonstrated that

when a husband left his village to work elsewhere, his absence often

enhanced his wife's position in the household and village, even as it

increased her work.17 Other scholarship tends to confirm the agency

of women and to locate its source in family, community and culture.

Over a decade ago, Nancy Frieden used the experience of physicians

to demonstrate how family networks of women resisted modernization

in childcare practices.18 More recently, Christine Worobec has ex-

plored at length the nature of women's position in peasant society and

culture.19 Without denying the reality of the patriarchal order, she

emphasizes women's abilities to utilize peasant patriarchy to their own

advantage, to accommodate themselves in order to benefit. Worobec

points out that women gained power as they aged: when a man became

head of the household, his wife was in a position to dominate her

daughters-in-law and to exert influence over her sons. Worobec also

draws attention to women's important roles in arranging marriages,

safeguarding family and community, and in transmitting culture to the

young. She does not deny, however, that the culture safeguarded and

transmitted by women remained deeply patriarchal. Thus far no his-

torian of Russian women has argued that women derived power and

sustenance from a semi-autonomous culture with its own ethos and

institutions, as have historians of the United States and western Eu-

rope.20

Current scholarship on Russian women does offer fresh perspec-

tives on the deployment of power on the political level by showing the

importance of stability in the family and in gender order to the main-

tenance of social and political stability. Whatever power women ex-

17. Barbara Alpern Engel, "The Woman's Side: Male Out-Migration and the Fam-

ily Economy in Kostroma Province," Slavic Review 45, no. 2 (Summer 1986): 257-71.

18. Nancy Frieden, "Child Care: Medical Reform in a Traditionalist Culture," in

The Family in ImperialRussia, 236-59.

19. Christine Worobec, Peasant Russia: Family and Communityin the Post-Emancipa-

tion Period (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991); "Accommodation and Resist-

ance," in Russia's Women,17-29; and "Victims or Actors? Russian Peasant Women and

Patriarchy," in Peasant Economy,Culture,and Politics of EuropeanRussia, 1800-1921, eds.

Esther Kingston-Mann and Timothy Mixter (Princeton: Princeton University Press,

1991), 177-206. See also Beatrice Farnsworth, "The Soldatka: Folklore and Court Re-

cord," Slavic Review 49, no. 1 (Spring 1990): 58-74; Mary Matossian, "The Peasant Way

of Life," in The Peasant in Nineteenth CenturyRussia, ed. Wayne Vucinich, (Stanford:

Stanford University Press, 1968), 1-40; and Antonina Martynova, "Life of the Pre-

Revolutionary Village as Reflected in Popular Lullabies," in The Family in Imperial

Russia, 171-85. The annotated bibliography at the end of this edited volume surveys

important primary, secondary and bibliographic literature on women and the family.

20. See the contributions by Ellen DuBois, Mari Jo Buhle, Temma Kaplan, Gerda

Lerner and Carroll Smith-Rosenberg to "Politics and Culture in Women's History: A

Symposium," Feminist Studies 6, no. 1 (Spring 1980): 26-64. On the basis of her reading

in secondary sources, Temma Kaplan applies this argument to the February revolu-

tion. See Temma Kaplan, "Women and Communal Strikes in the Crisis of 1917-1922,"

in BecomingVisible: Womenin EuropeanHistory, eds. Renate Bridenthal, Claudia Koonz

and Susan Stuard, 2nd ed. (Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1987), 430-38.

This content downloaded on Wed, 9 Jan 2013 06:54:48 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

314 Slavic Review

ercised within it, the patriarchal order in peasant villages-indeed, in

all of Russian society-was sanctioned and buttressed by law because

it fostered discipline and respect for state authority.2' To buttress pa-

triarchal authority by providing a refuge for illegitimate children who

were evidence of the family's inability to control its members, in the

eighteenth and nineteenth centuries under circumstances of rapid so-

cial change, the state instituted foundling homes.22 Aware of the con-

nection between the patriarchal family and an authoritarian political

order, radicals of the 1850s and 1860s attacked the patriarchal family

and attempted to liberate women from its authority (the bolsheviks

would do the same half a century later). The state responded with

repression: women living outside the family became suspect, even if

their sole objective was to obtain an education. State concern with

women's place shaped women's struggle for higher education in the

second half of the nineteenth century, as ChristineJohanson has dem-

onstrated.23 Aware that their quest challenged conventional ideas about

women's roles, feminists took care to avoid threats to the traditional

family structure and to stress the social utility of women's education.

By cooperating with the government and avoiding confrontation, fem-

inists succeeded in gaining for qualified women access to university

degrees and medical study. But these gains were always endangered by

the involvement of a radical minority of women. Although she does

not emphasize the point, Johanson's research suggests that in the minds

of conservative government officials, social stability depended upon

the relegation of middle- and upper-class women to their proper

spheres.

Similar concerns conditioned official responses to the growing

numbers of peasant women who migrated to the cities and factories

in search of employment. While migrant women's working and living

conditions were often no easier than they had been in the village, they

experienced a new kind of independence, as well as a greater vulner-

ability.24 And although women often remained psychologically and

legally tied to the village, they were nevertheless no longer directly

subject to patriarchal control of their behavior, their sexual behavior

in particular.25 High illegitimacy rates in Russia's major cities provided

21. William Wagner, "The Trojan Mare: Women's Rights and Civil Rights in Late

Imperial Russia," in Civil Rights in Imperial Russia, eds. Olga Crisp and Linda H. Ed-

mondson (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 65-84.

22. David Ransel, iMothers of Misery: Child Abandonment in Russia (Princeton:

Princeton University Press, 1988).

23. Christine Johanson, Women'sStrugglefor Higher Educationin Russia, 1855-1900

(Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1987). For a survey of women

students, see Ruth Dudgeon, "The Forgotten Minority: Women Students in Imperial

Russia, 1872-1917," Russian History 9 (1982): 1-26.

24. Rose Glickman discusses the lives of factory women; material on the life of

domestic servants can be found in David Ransel, Mothersof Misery. Domestic service,

which employed the largest proportion of urban working women at least until 1914,

merits further study.

25. On village controls, see Barbara Alpern Engel, "Peasant Morality and Pre-

This content downloaded on Wed, 9 Jan 2013 06:54:48 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Notes and Comments 315

statistical evidence of the difference between town and country.26 But

the growth of prostitution was the most visible and troubling symbol

of women's freedom from patriarchal control and it moved the state

to action.27 Suspecting all lower-class women without families of "trad-

ing in vice," the state attempted to substitute its own patriarchal power

for absent husbands and fathers. It created and elaborated a network

of laws to regulate prostitution and control venereal disease, laws that

in fact affected all women of the lower classes. Even women who plied

the trade casually and intermittently (or perhaps not at all) risked

receiving a "yellow ticket" from the police.28 A "yellow ticket" was a

permit for prostitution that subjected women to police surveillance

and medical supervision, allegedly in order to control venereal disease

but really to control the women themselves, as Laura Engelstein has

contended.29 Once registered as a professional prostitute, a woman on

her own would no longer be her own mistress. State investment in

upholding the traditional gender order also rendered women's bodies

tokens of the authority contested by educated society. William Wagner

has argued that jurists' efforts to expand the individual's civil rights by

expanding women's rights was part of a more general social and po-

litical -struggle from the 1860s onwards.30 But conservative jurists

blocked legal reform by maintaining that respect for state authority

derived from-the respect for patriarchal authority fostered by the fam-

ily. To undermine the one was to undermine the other.

Wagner also points out that the liberal argument for women's rights

impeded women's cause because it made legal advances for women

contingent on broader civil rights.31 And jurists' efforts to revise the

laws that treated sexual crime and prostitution served men more than

they served women: Laura Engelstein's analysis of the language of legal

reforms reveals how jurists denied women agency and ensured that

individual autonomy remained a male preserve.32 Physicians likewise

Marital Relations in Late Nineteenth Century Russia,"Journal of Social History 23, no.

4 (Summer 1990): 695-714; and Christine Worobec, "Temptress or Virgin? The Pre-

carious Sexual Position of Women in Postemancipation Ukrainian Peasant Society,"

Slavic Review 49, no. 2 (Summer 1990): 227-38.

26. David Ransel, "Problems in Measuring Illegitimacy in Prerevolutionary Rus-

sia," Journal of Social History 16 (Winter 1982): 111-27.

27. On prostitution in Russia, see Richard Stites, "Prostitute and Society in Pre-

Revolutionary Russia,"JahrbiicherfiirGeschichteOsteuropas31, no. 3 (1983): 348-64; and

Barbara Alpern Engel, "St. Petersburg Prostitutes in the Late Nineteenth Century: A

Personal and Social Profile," Russian Review 48, no. 1 (1989): 21-44.

28. On the "yellow ticket," see Laurie Bernstein, "Yellow Tickets and State-Li-

censed Brothels: The Tsarist Government and the Regulation of Urban Prostitution,"

in Health and Societyin RevolutionaryRussia, eds. Susan Gross Solomon and John Hutch-

inson (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), 45-65.

29. Laura Engelstein, "Morality and the Wooden Spoon: Russian Doctors View

Syphilis, Social Class, and Sexual Behavior, 1890-1905," Representations 14 (Spring

1986): 169-208.

30. Wagner, "The Trojan Mare," 84.

31. Ibid.

32. Laura Engelstein, "Gender and the Juridical Subject: Prostitution and Rape

This content downloaded on Wed, 9 Jan 2013 06:54:48 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

316 Slavic Review

used women as the basis for claims to greater authority: those who

disliked official regulation of prostitution, for example, argued that

medical authority should replace it.33Ironically, in the scholarship on

gender and power, as in the discourse itself, women only rarely figure

as actors or as agents on their own behalf.

Yet as a civil society began to take shape in Russia in the late

nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, women, like men, claimed

larger and more autonomous social roles. In some cases, women did

so by extending their customary sphere. In religious communities, for

example, women moved from contemplation to acts of charity for the

poor and to education of the young. Especially in rural areas, these

women's communities remained relatively free of the bureaucracy

which continued to be suspicious of any private initiative or inde-

pendent action.34 Women teachers in St. Petersburg fought for the

right to enjoy their customary sphere, to be wives and mothers, as well

as professionals. Protesting regulations that forbade women teachers

to marry, they banded together to claim that right and to control their

own personal lives. In their struggle with the city Duma, the teachers

found allies in the re-emergent feminist movement which sought to

expand women's civil rights and after 1905 to gain for women the

vote.35

Feminists in Russia, like radicals, contested the authority of the

state. When women sacrificed themselves for radical causes, they gained

the respect and admiration of their male comrades. But when women

pursued a feminist cause, men were more ambivalent despite the fact

that feminists collaborated with leftist and liberal men far more exten-

sively than they did in Europe or the United States.36 During the rev-

olution of 1905, only a minority of men in the opposition movement

were willing to endorse the feminists' call for women's suffrage, fore-

most among them the peasant-dominated Trudovikgroup. The Cadets

were divided over the issue, while other leftist parties were suspicious

and reluctant to support "bourgeois feminism."

The ambivalent relation of socialism to feminism persisted across

the rupture of 1917. After the October revolution, feminism disap-

peared as an independent political and intellectual current: "bourgeois

feminism" became (and remained) a pejorative term, used by a male

leadership when women articulated needs that diverged too far from

in Nineteenth-Century Russian Criminal Codes," Journal of Modern History 60, no. 3

(September 1988): 458-95.

33. Laura Engelstein, "Morality and the Wooden Spoon."

34. Brenda Meehan-Waters, "From Contemplative Practice to Charitable Activity:

Russian Women's Religious Communities and the Development of Charitable Work,

1861-1917," in Lady Bountoiul Revisited Women,Philanthropyand Power, ed. Kathleen

McCarthy (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1990), 142-57.

35. Christine Ruane, "The Vestal Virgins of St. Petersburg: School Teachers and

the 1897 Marriage Ban," Russian Review 50, no. 2 (April 1991): 163-82.

36. Linda Harriet Edmondson, The Feminist Movementin Russia, 1900-1917 (Stan-

ford: Stanford University Press, 1984); and Stites, The Women'sLiberationMovement.

This content downloaded on Wed, 9 Jan 2013 06:54:48 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Notes and Comments 317

theirs. Nevertheless, varieties of bolshevik feminism became part of

the political discourse and the bolsheviks tried to fulfill the radical

promise to do away with the patriarchal family. In 1918, they issued a

code that equalized women's status with men's, removed marriage from

the hands of the church, allowed a marrying couple to choose either

the husband's or the wife's surname and granted illegitimate children

the same legal rights as legitimate ones. Divorce, virtually impossible

in the tsarist period, became easily obtainable. In 1920, abortion be-

came legal if performed by a physician. The revolution unleashed not

only a flood of experimentation in personal lives and in the culture,37

it also provided unprecedented opportunities for lower-class women

to speak and act on their own behalf. The Women's Bureau (Zhenotdel)

was established in 1919 as a result of the efforts of bolshevik women

such as Inessa Armand and Aleksandra Kollontai who produced some

remarkable theoretical work with a marxist approach to women and

women's issues that raised sexuality and sexual relations as proper

topics for political discussion.38 During the 1920s, the Women's Bureau

tried to organize working women to bring them into the revolutionary

process and to promote their equality in public and private life.

Hundreds of thousands of lower-class women served as delegatkiof the

Zhenotdel.39

Yet even as they challenged the patriarchal family and mobilized

women to an unprecedented degree, many bolshevik cadres resisted

women's emancipation and barely concealed their contempt for the

Zhenotdel. From the first, gender differences were subtly re-inscribed

in the revolutionary iconography which consistently depicted the he-

roic worker as male and women as helpers of man or as "Mother

Earth."40Proletcul't artists and writers also reinforced the image of the

working class and its institutions as male while they relegated women

to the family. For them, as for much of the bolshevik leadership, wom-

en's "backwardness" and their power in the family constituted a threat

to the revolution.4" Although devoted to the ideal of a genuinely eman-

cipated woman, even the Zhenotdel avoided challenges to women's

37. Richard Stites, RevolutionaryDreams: Utopian Vision and ExperimentalLife in the

Russian Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989). Surprisingly, this book

has rather little to say about the role of women or about gender in post-revolutionary

utopian visions.

38. On Kollontai, see Clements, BolshevikFeminist;and Farnsworth, AleksandraKol-

lontai. For Kollontai's writings, see SelectedWritingsof AlexandraKollontai, ed. Alix Holt

(Westport, CT: L. Hill, 1977); and the analysis in Mary Buckley, Womenand Ideologyin

the Soviet Union (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1989), 44-57.

39. On the Zhenotdel, see Stites, The Women'sLiberationMovement,Carol Hayden,

"The Zhenotdel and the Bolshevik Party," Russian History, 3 (Fall 1976): 150-73; and

Buckley, Womenand Ideology.

40. Elizabeth Waters, "The Female Form in Soviet Political Iconography, 1917-

1932," in Russia's Women,225-42 and Victoria Bonnell, "The Representation of Women

in Early Soviet Political Art," Russian Review 50, no. 3 (July 1991): 267-88.

41. Lynn Mally, Cultureof the Future:TheProletkultMovementin RevolutionaryRussia

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), chap. 6.

This content downloaded on Wed, 9 Jan 2013 06:54:48 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

318 Slavic Review

42

traditional roles when they addressed audiences of lower-class women.

On the other hand, Wendy Goldman has criticized the tendency to

view ideology and politics as the ultimate arbiter of the historical pro-

cess; she argues instead that historians should look to both the material

possibilities and the actions of working women. She emphasizes that

economic factors hampered Zhenotdel efforts to establish child-care

centers, communal dining halls and other services, and that the vast

majority of the Zhenotdel's constituency was illiterate, unorganized

and largely unresponsive to feminist appeals.43 In fact, as Barbara

Clements demonstrates, the revolution in many ways worsened wom-

en's lot, at least in the short run: revolution and civil war had taken

away their men and had destroyed their fragile family economies.44

What could promises of sexual equality mean to an unemployed work-

ing woman or to a peasant woman without access to land in her own

right? Rates of female unemployment remained high through the 1920s.

Moreover, revolutionary transformation lessened women's loyalty nei-

ther to their families nor especially to their children; but food short-

ages, poor housing, lack of job opportunities and especially family

instability made women's traditional responsibilities considerably

heavier.

These grim realities shaped lower-class women's responses to the

New Family Code of 1926, which not only facilitated divorce but also

proposed that women in de facto unions have the same legal protec-

tion as women in registered marriages. Parts of the nationwide debates

over the Code were published, allowing working-class and peasant

women to articulate their opinions openly, and so giving historians a

rare glimpse into their thinking.45 Wendy Goldman and Beatrice

Farnsworth both argue that the debates foreshadowed the conservative

trends of the 1930s, although they arrive at this conclusion by very

different routes. Farnsworth stresses ideology and contends that bol-

shevik social policy in the 1920s was basically conservative, aimed at

maintaining marital and family stability. She presents as evidence the

failure of the party to take up a general insurance fund that would

support and maintain the independence of unwed mothers.46 Gold-

42. Barbara Evans Clements, "The Birth of the New Soviet Woman," in Bolshevik

Culture:Experimentand Orderin the Russian Revolution,eds. Abbott Gleason, Peter Kenez

and Richard Stites (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985), 220-37.

43. Wendy Goldman, "Women, the Family, and the New Revolutionary Order in

the Soviet Union," in PromissoryNotes: Womenin the Transition to Socialism, eds. Sonia

Kruks, Rayna Rapp and Marilyn Young (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1989), 59-

81.

44. Barbara Evans Clements, "Working Class and Peasant Women in the Russian

Revolution," Signs 8, no. 2 (1982): 215-35; and "The Effects of the Civil War on Women

and Family Relations," in Party, State, and Societyin the Russian Civil War:Explorations

in Social History, eds. Diane Koenker, William Rosenberg and Ronald Suny (Blooming-

ton: Indiana University Press, 1989), 105-22.

45. Excerpts from the debates are reproduced in TheFamilyin the USSR:Documents

and Readings, ed. Rudolf Schlesinger (London: Routledge and Paul, 1949).

46. Beatrice Farnsworth, '"'BolshevikAlternatives and the Soviet Family: The 1926

Marriage Law Debate," in Womenin Russia, eds. Dorothy Atkinson et al., 139-66.

This content downloaded on Wed, 9 Jan 2013 06:54:48 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Notes and Comments 319

man, by contrast, stresses social causes and highlights the "conserva-

tism" of lower-class women themselves. She shows that these women

opposed the provisions of the New Code because they believed that it

would encourage male irreponsibility and further erode family stabil-

ity.47 Barbara Clements holds that the two kinds of conservatism in-

teracted to result in the bolshevik approach tailored to suit their au-

dience of working-class and peasant women. Fearful of alienating

potential supporters and eager to enlist lower-class women in support

of the revolution, bolsheviks softened the emancipatory features of

new Soviet womanhood by incorporating elements of a traditional

feminine ideal.48

Research on women in the 1930s reveals other forms of women's

resistance to bolshevik policies. Both collectively and individually,

women defended their interests against the growing power of the state:

peasant women rioted in opposition to the collectivization and the

eradication of their family farms;49on an individual level, women re-

fused to relinquish to the state control over their sexuality. Upon re-

vocation of the right to abortion in 1936 which deprived them of their

primary means of birth control, women subjected themselves to back-

alley abortions and dangerous home-remedies to limit their fertility so

that they might take advantage of education and industrialization.50

Sources for women's history in the period after the early 1930s

have been fewer than for earlier periods so that women's voices of that

time seemed virtually inaudible. Except for stirring accounts of per-

sonal suffering and repression,51 the sources are primarily official. They

offer reports of policies affecting women, of ideas about women or of

images of women, all of which present a grim picture. The exception

is the Smolensk archive, which historians of women are just starting

to mine. And although the opening of Soviet archives is now changing

the picture dramatically, published work does not as yet reflect that

change.

Since the 1930s, women have shouldered the burden of full-time,

waged labor while continuing to do almost all housework without la-

bor-saving devices. Their burden is especially heavy in villages, where

47. Wendy Goldman, "Freedom and its Consequences: The Debate on the Soviet

Family Code of 1926," Russian History 11 (Winter 1984): 362-88.

48. Barbara Clements, "The Birth of the New Soviet Woman," in BolshevikCulture,

220-37.

49. Lynne Viola, "Bab'i bunty and Peasant Women's Protest during Collectiviza-

tion," Russian Review 45, no. 1 (January 1986): 23-42.

50. Wendy Goldman, "Women, Abortion and the State, 1917-36," in Russia's

Women,243-67.

51. The most well known of these are Nadeihda Mandelshtam, Hope Against Hope

(New York: Atheneum, 1970); and Eugenia Ginzburg,Journey Into the Whirlwind(New

York: Harcourt Brace and World, 1967). Raisa Orlova in Memoirs(New York: Random

House, 1983) provides a thoughtful recounting of the Stalin years. Elena Kochina in

BlockadeDiary (Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1990) provides a harrowing account of the siege of

Leningrad.

This content downloaded on Wed, 9 Jan 2013 06:54:48 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

320 Slavic Review

work-days are longer and the amenities even scarcer than in the cities.

(As late as 1976, the vast majority of rural housing lacked running

water.52) As in the west, Russian women in both village and city are

clustered in poorly paid sectors of the workforce, are inadequately

represented in managerial positions and have been excluded from

positions of genuine political power.53

Since the 1960s, gender differences have acquired the status of

scientific truth from which few dissent publicly: these differences are

immutable, biologically and not socially created, and include women's

"natural" roles of motherhood and childrearing.54 Nevertheless, alter-

native interpretations of women's roles and experiences are beginning

to be heard and some of them are self-consciously feminist.55 After the

death of Stalin, the debate on the woman question was revived and,

in the recent past, it has broadened so dramatically that it is impossible

to know where it will lead.56 As Russians currently attempt to define

for themselves a new social and political order, they almost inevitably

invoke notions of an appropriate gender order as well. Elizabeth Waters

has provided an astute commentary on the engendering of the dis-

course on current changes.57

The Russians' current fascination with their own history is slowly

extending to the history of women;58 they have a lot to learn as do we.

52. Susan Bridger, Womenin the Soviet Countryside:Women'sRoles in Rural Develop-

ment in the Soviet Union (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987).

53. See Lapidus, Womenin Soviet Society;Norton Dodge, Womenin the Soviet Econ-

omy: Their Role in the Economic, Scientyifcand Technical Development(Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University Press, 1966); Michael Sacks, Women'sWork in Soviet Russia: Conti-

nuity in the Midst of Change(New York: Praeger, 1976); Buckley, Womenand Ideology;and

the essays by Sacks, Dodge, Chapman and Moses in Womenin Russia, eds. D. Atkinson

et al.

54. Mollie Rosenham, "Images of Male and Female in Children's Readers," in

Womenin Russia, eds. D. Atkinson et al., 293-306; Lynne Attwood, The New Soviet Man

and Woman:Sex-RoleSocialization in the USSR (Bloomington: Indiana University Press,

1990); and the essays by Attwood, McAndrew, Peers, Holland and McKevitt in Soviet

Sisterhood.Even Soviet writers who seem "feminist" in other respects endorse stereo-

typed views of women as is clear from the essays in Women,Work,and Family in the

Soviet Union, ed. Gail Warshofsky Lapidus (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1982).

55. On Soviet feminists, see Alix Holt, "The First Soviet Feminists," in Soviet

Sisterhood,237-65; and Rochelle Ruthchild, "Sisterhood and Socialism: The Soviet

Feminist Movement," Frontiers:A Journal of Women'sStudies 7, no. 2 (1983): 4-12. In

1987, a new feminist samizdat entitled Women'sReadings (ZhenskoeChtenie)appeared in

Leningrad, edited by Olga Lipovskaia. See Barbara Alpern Engel, "An Interview with

Olga Lipovskaia," Frontiers 10, no. 3 (1989): 6-10. Some feminist dissident writings

have been collected and published in Womenand Russia. Feminist Writingsfrom the Soviet

Union, ed. Tatyana Mamonova (Boston: Beacon Press, 1984). An earlier collection of

feminist writings was published in England: Womanand Russia. The First Feminist Sam-

izdat (London: Sheba Feminist Publishers, 1980).

56. Buckley, Womenand Ideology,is especially good on recent developments in

Soviet thinking about women.

57. Elizabeth Waters, "Restructuring the 'Woman Question': Perestroika and

Prostitution," Feminist Review, no. 33 (Autumn 1989): 3-19. A prime example of the

invocation of gender is Valentin Rasputin, "Women Mirror our Entire Culture,"

Perestroika,no. 3 (1991): 32-39. I am very grateful to Elizabeth Waters for sending this

article to me.

58. For example, in February 1991, a conference on "Feminism in Russian Cul-

This content downloaded on Wed, 9 Jan 2013 06:54:48 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Notes and Comments 321

Despite the solid foundation that has been built over the last few dec-

ades, much work remains to be done. Some of the more obvious ex-

amples are: explorations of the prescriptive literature or religious

teachings concerning women's roles in the pre-revolutionary period;

social or economic histories of noblewomen, merchant women, women

of the urban petty bourgeoisie (meshchanstvo),professional women and

women of the clerical estate.59 We still know very little about the roles

that women played in the emergent civil society of late imperial Russia

or in Soviet society, or about the ways that gender structured both.

(Doubtless, women's religious or family values Provided alternatives to

official ideology after the bolshevik revolution. 0) The research agenda

could be extended almost indefinitely, especially if cognate fields such

as the history of private life, of sexuality, of the family, are included.

Work on women and gender holds the promise not only of correcting

assumptions about the universality of men's experience, but also of

providing fresh perspectives on Russia's past and on the nature and

sources of historical change.

ture" was held in Leningrad. A substantial portion of the papers was provided by

historians. A similar conference was planned forJanuary 1992 but canceled.

59. References to women of the clerical estate can be found in Gregory Freeze,

"Caste and Emancipation: The Changing Status of Clerical Families in the Great Re-

forms," in The Family in ImperialRussia, 124-50.

60. For the impact of grandmothers, for example, see Ludmilla Alexeyeva and

Paul Goldberg, The Thaw Generation:Comingof Age in the Post-StalinEra (Boston: Little,

Brown and Company, 1990), 11-12.

This content downloaded on Wed, 9 Jan 2013 06:54:48 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- V2 Herencias y Perspectivas Marxismo N28-1Document76 pagesV2 Herencias y Perspectivas Marxismo N28-1Marcos TorresNo ratings yet

- Adminpujojs,+artículo+1Document22 pagesAdminpujojs,+artículo+1Marcos TorresNo ratings yet

- The Empirical Strenght of The Labour Theory PF ValueDocument28 pagesThe Empirical Strenght of The Labour Theory PF ValueMarcos TorresNo ratings yet

- Las Contradicciones de La Revolución en La Lucha Kurda y La Economía Anticapitalista de RojavaDocument315 pagesLas Contradicciones de La Revolución en La Lucha Kurda y La Economía Anticapitalista de RojavaMarcos TorresNo ratings yet

- 1394929Document29 pages1394929Marcos TorresNo ratings yet

- Organizing Women Before and After The Fall: Women's Politics in The Soviet Union and Post-Soviet RussiaDocument33 pagesOrganizing Women Before and After The Fall: Women's Politics in The Soviet Union and Post-Soviet RussiaMarcos TorresNo ratings yet

- La Recepcion Del Debate Sobre Las Construcciones Racionales y Las Reconstrucciones Contextuales en 1988Document17 pagesLa Recepcion Del Debate Sobre Las Construcciones Racionales y Las Reconstrucciones Contextuales en 1988Marcos TorresNo ratings yet

- El Concepto de Plasticidad en Las Primeras Obras DDocument24 pagesEl Concepto de Plasticidad en Las Primeras Obras DMarcos TorresNo ratings yet

- Damiano Tagliavini y Ignacio Sabbatella (2011) - Apuntes para La Construcciã N de Una Ecologã A MarxistaDocument24 pagesDamiano Tagliavini y Ignacio Sabbatella (2011) - Apuntes para La Construcciã N de Una Ecologã A MarxistaMarcos TorresNo ratings yet

- Do Corporate Tax Cut Boost Economic Growth?Document15 pagesDo Corporate Tax Cut Boost Economic Growth?Marcos TorresNo ratings yet

- Carta de Marx A SorgeDocument2 pagesCarta de Marx A SorgeMarcos TorresNo ratings yet

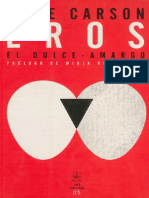

- Carson Anne - Eros El Dulce - AmargoDocument237 pagesCarson Anne - Eros El Dulce - AmargoMarcos Torres100% (1)

- Ejemplo de Problema FilosóficoDocument1 pageEjemplo de Problema FilosóficoMarcos Torres75% (4)