Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Blair, Steven N., Et Al. Physical Fitness and All-Cause Mortality A Prospective Study of Healthy Men and Women

Blair, Steven N., Et Al. Physical Fitness and All-Cause Mortality A Prospective Study of Healthy Men and Women

Uploaded by

12trader0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views7 pagesOriginal Title

Blair, Steven N., Et Al. Physical Fitness and All-cause Mortality a Prospective Study of Healthy Men and Women

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views7 pagesBlair, Steven N., Et Al. Physical Fitness and All-Cause Mortality A Prospective Study of Healthy Men and Women

Blair, Steven N., Et Al. Physical Fitness and All-Cause Mortality A Prospective Study of Healthy Men and Women

Uploaded by

12traderCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 7

Original CONtribUtiONS ttt

Physical Fitness and All-Cause Mortality

A Prospective Study of Healthy Men and Women

‘Steven N. Blait, PED; Harold W. Koh! Ill, MSPH; Ralph S, Paffenbarger, Jr, MO. DrPH; Debra G. Clark, MS;

Kenneth H. Cooper, MD, MPH; Larry W. Gibbons, MD, MPH

We studied physical fitness and risk of all-cause and cause-specttic mortality in

10 224men and 3120 women who were given a preventive medical examination.

Physical fitness was measured by a maximal treadmill exercise test. Average

{follow-up was slightly more than 8 years, for a total of 110.482 person-years of

observation. There were 240 deaths in men and 43 deaths in women. Age-

adjusted all-cause mortality rates declined across physical fitness quintiles from

64.0 per 10 000 person-years in the least-fitmen to 18.6 per 10 000 person-years

in the most-fit men (slope, ~ 4.5). Corresponding values for women were 39.5

er 10.000 person-years to 8.5 per 10000 person-years (slope, — 5.5). These

trends remained after statistical adjustment for age, smoking habit, cholesterol

level, systolic blood pressure, fasting blood glucose level, parental history of

coronary heart disease, and follow-up interval. Lower mortality rates in higher

fitness categories also were seen for cardiovascular disease and cancer of

combined sites. Attributable risk estimates for all-cause mortality indicated that

low physical fitness was an important risk factor in both men and women. Higher

levels of physical fitness appear to delay all-cause mortality primarily due to

lowered rates of cardiovascular disease and cancer.

PHYSICAL activity is inversely associ-

ated with morbidity und mortality from

several chronie diseases. The apparent-

ly protective effect of a more active life

is seen for occupational activity and

death from cardiovascular disease! and

colon cancer,’ and for leisure-time phys-

ieal activity and cardiovaseular dis

ease." Higher levels of leisure-time

physical activity are associated with in

creased longevity in eollege alumni.

‘These associations of sedentary habits

to health appear to be independent of

confounding by other well-established

For editorial comment see p 2437.

risk factors.’ Furthermore, the rela-

tionship of physical fitness (an attri-

bute) to physical activity (a behavior)

and disease rates is controversial," and

it is uncertain whether physical zetivity

sufficient to increase physical fitness is

required for health benefits.

In contrast to physical activity, pub-

lished studies on physical fitness and

mortality are few, typically with fewer

than 20000 person-years of follow-up,

and usually limited to men, Physieal ac~

tivity is an important determinant of

~Fromine inser rabies Resench Dales Tex

Raping eaests 9 the nse es ooo Fe

search, 12830 ester Re Oss, 76230 0 fia)

JAMA, November 3, 1989—Vo! 262, No. 17

(LAMA. umsranecenn-2

ness is an objective marker for habitual

physical activity. Physical fitness ean be

measured more objectively than physi=

‘al activity, and thus may be more u

ful clinically. Research studies that in-

clude the measurement of physical

fitness may provide additional insight

into the contribution of a physically ac-

tive way of life to decreased risk of mor-

bidity and mortality.

Here, we report all-cause and cause-

specific’ mortality by physical fitness

categories in men and women followed

up for 110 482 person-years, or an aver-

age of more than 8 years,

SUBJECTS AND METHODS.

Subjects

‘The 13344 study participants com-

prised 10224 men and 3120 women who

received a preventive medical examina-

tion at the Cooper Clinie in Dallas, Tex,

during 1970 to 1981. Patients were in

cluded in the study if they were resi-

dents of the United States at their frst

clinie visit, had a complete examination,

and achieved at least 85% of their age:

predicted maximal heart rate ona

‘treadmill exercise test at the baseline

linie visit. Patients not achieving this

‘maximal heart rate standard were pre-

‘sumed to be more likely to have preex-

isting disease or be receiving medica-

tion with B-blockers, These conditions

Would be associated with poorer tread.

rill est performance and higher risk of

death during follow-up. Thus, excluding

patients with these characteristics is a

conservative decision that reduces the

chance of finding a spurious inverse re-

lationship hetween fitness and mortal-

wy. At baseline, all patients had no

personal history of heart attack, hyper

tension, stroke, or diabetes: no resting

electrocardiographie (ECG) abnormali-

ties; and no abnormal responses on the

exercise BCG.

Clinical Examination

‘The baseline examination was given

alter an overnight fast of at least 12

hours and after patients gave their in

formed consent, The examination was 2

complete preventive medical evaluation

that. ineluded a personal and family

health history, a physical examination,

a questionnaire on demographie charac.

teristiesand healthhabits, anthropome-

try, resting ECG, blood chemistry

tusts, blood pressures, and a maximal

treadmill exercise test. Examination

‘methods and procedures followed 2

standard manual of operations and have

been described further in earlier re-

ports." All patients were free of

known chronie disease as determined by

the following criteria: no personal his-

tory of heart attack, hypertension,

stroke, or diabetes; no resting ECG ab-

xnormalities; and no abnormal responses

onthe exercise ECG.

Physical fitness was measured by a

maximal treadmill exercise test.”

‘Treadmill speed was set initially at

‘88mv/min. The grade was 0% for the first

minute, 29 the second minute, and in-

ereased 1% each minute until 25 min-

utes. After 25 mimutes, the grade did

not change and speed’ was increased

5.4 m/min each minute until test termi-

nation, Patients were given encourage-

ment to give maximal effort. ‘Total

treadmill test time in seconds was the

variable used in analysis. ‘Treadmill

‘time from this protocol is highly corre-

lated with measured maximal oxygen

Physica Fitness and Moralty—Blairetal 2308

uptake in men‘ (7.92) and women*

(r=.94), which is the most widely

accepted index of eardiorespiratory fit-

ness.

Patients were assigned to physical

fitness categories based on their age,

sex, and maximal time on the treadmill

test, Tresdmill-time quintiles were de-

termined for each age and sex group.

Individuals with a treadmill time in the

first quintile were assigned to the low-

fit group. Those with scores in the sec-

ond through the fifth quintiles consti-

tuted fitness groups 2 through 5,

respectively. This, assignment to a

ness ealegory was based on age and sex

norms of treadmill performance rather

than by an absolute fitness standard.

(Treadmill-time quintile cutoff points

for each age group for men and women

may be obtained from us.)

Cigarette-smoking status was deter-

mined from the medical questionnaire.

Patients who reported smoking at pre~

sent or within the 2 years preceding the

baseline examination were designated

as current smokers. This conservative

definition for smoking was adopted be-

cause many smokers may have quit tem-

poratily in preparation for their preve

tive medical examination, and mortality

risk for recent quitters is similar to eon-

tinuing smokers." Results from the

smoking analyses were essentially un-

changed when current smoking was de-

fined as cigarette smoking at baseline or

during the year preceding the exami-

nation

Height and weight were measured on

a standard physician’ seale, and body

‘mass index was calculated (kilograms

per meter squared). Blood pressure was

measured by the auscultatory method

with a mereary sphygmomanometer,

diastolic pressure being recorded as the

disappearance of sound, Serum samples

were analyzed for cholesterol and glu-

cose by automated techniques.

Mortality Surveillance

Study subjects were followed up for

mortality from their first clinie visit

through 1985. The average length of fol.

low-up was slightly more than 8 years,

and the total follow-up experience for

the cohort was 110482 person-years,

Several follow-up methods were used.

Decedents were identified by reports

from family, friends, and business asso-

ciates; responses to appointment re-

minders; and other mailings from the

clinic. The entire cohort was sent acase-

finding and disease-identifying ques-

tionnaire in 1982." Nonrespondents

were followed-up via the Social Security

Administration files, the Department of

Motor Vehicles in the subject’ state of

residence, and a nationwide eredit bu-

2306 JAMA, November, 1989 vol 262, No.17

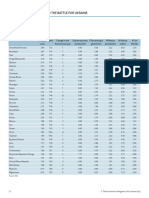

‘Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Suvving and Deceased Male and Female Patents, Aerobics Center

Longtudna Soy. 1970 10 1981

Surviving

(oro5e)

7 z sp

ag, ae as

5h contdence ks) (1.4.7)

Wig i wie at

{259% coience hts) (317.821)

Figs, on Was 63

(0694 corience Has) (1787. 709)

Bea, mass inden 256 38

(Gist eontaerce is) (255, 257)

Feagemaane To er

(ss% conieence tts) (hor, 022)

Fotomun y aa 28

{5h coiionce nis) (23.85)

Taalcroksteol lee mmol S450

{95% confidence is) 66.54

Bysesc Hood pressure, mimtg 1204197

"ose conerce ts) 2b, 2019)

Dac tingg esr, wag 7878

{95% contigence hers) | 79.5, 799)

‘rere smokes 285

Deceased Deceased

— ae

i 0 zs

oe as 99 Si as

oasis “era. 560)

m2 133 Sop 07607 9a

wise “basco “ere.639)

Wo; gi ies 66 iar 86

928) “Treas. 1550) “0624, 1658)

28 2235 m2 a7

(54.25) “een.ees)ees.249)

ar ot O aa 50

(726.56) (ee2,680) “tava. s60)

Bs ao a2 28 es ae

60.70) re “Gar6)

aT

(80.62 iSt7.52)_“er,ea)

agra 4d 198

tiesov03) “innizan__‘Gibs, wos)

Cra aS 702-94

(10.000 742.748) “764,420,

ws Ba Re

—————

eau network, The National Death In-

dex has been used since it was estab-

lished in 1979 to search for possible

matches inthis cohort. Finally, individ-

uals with unknown vital status and with

a Dallas-area address were checked in

local telephone directories, Follow-up

has been difficult. since patients come

from all 50 states and are mobile and

since a significant portion of the follow-

up occurred prior to the establishment.

of the National Death Index. Despite

these limitations, vital status has been

ascertained for 95% ofthe cohort.

‘There have been 283 deaths in the

study group, Official death certificates

were obtained from the states. ‘The un-

derlying cause and up to four eontribut-

ing eauses of death were coded by a

nosologist according to the Internation-

al Classification of Diseases, Ninth

Edition, Revised.

Data Analysis

A total of 288 deaths were identified

in the cohort over the average of ap-

proximately 8 years of follow-up. Mor-

tality rates per 10000 person-years of

{follow-up were computed for each of the

five fitness categories and age-adjusted

by the direct method, using the total

experiencein the populiationas the stan-

dard, Age differences were adjusted by

the following groupings: 20 to 39, 40 to

49, 50 to 59, and 60 or more years. These

rates were then used to compute rela-

tive risks (RR) of death for each fitness

‘quintile as well as for examination of the

role other variables played in confound-

ing the relationship between fitness and

mortality. Attributable risk percent

ages (etiologic fractions) for those

{groups exposed to adverse characteris-

ties were ealeulated 2s were population-

based estimates of attributable risks.”

Multiple logistic regression was used

to estimate RRs of death among the

fitness quintiles after control for associ-

ated confounding risk factors." Interval

estimation was used to ealeulate confi-

dence intervals (Cs) around point esti-

mates of risk.

RESULTS

Patients n this study are from middle

to upper sociveconomie strata; approxi

ately 70% are college graduates. Most

are employed in professional, exeeu-

tive, or white-collar position’. More

than 9 are white. Baseline character-

isties on selected demographic and clini

cal variables are shown in Table I. Dece-

dents were somewhat older, less

physically fit, and had less favorable

sk profiles,

Table 2 shows the age-adjusted all-

cause death rates by physical fitness

categories in men and women, Relative

risks of death with the 95% Cls are

shown with the mostft quintile as the

reference category. Less-ft individuals

hada higher risk ofdeath than the more-

fit men and women. Increased RR for

all-cause mortality’ was significantly

higher for the lesst-fit quintile in men,

and for the two least-fit quintiles in

Women. The 95% Cls for the test for

linear trend across Gtness categories

did not include 1.0 in either men or

women,

Univariate age-adjusted RR for all-

‘cause mortality for several important

clinieal and life-style variables for men

and women are presented in Table 3.

Physical ness anc Mortality—Blairetal

‘Table 2.—Age-Adustes AB-Cauce Death Rates par 10000 Person Years of Follow-up (1970 to 1985) by

Physical Fines Groups n Men and Women inthe Aerobics Center Longhunal Study

SS

=e =

vot nARrpaSo rahe

|| Seeeerwoee | ee

1 0

= 5

= 7

= mr

= = :

xs az2%8

i Bs fois

@ a eens 10

‘ a ey]

7 s FF 10)

Se eee zt

‘fest for linear Wend, slope ~ 5.5; 95% contigence lis. -$.2, - 1.9. gs +10}

“Table 3.—Petatve Fisk for ALCause Motay to: Selected Cirical and Lte-syle Venables, Men and

Women the Aerobics Centr Longitudinal Study

Guenter or aut npaslay_

Ener parent hd of coronary heart daease

‘Serum glos9 98 7

Serum etoeseottvel 6.20 meno.

150,494

Boy macs ex 269

‘Curent ereker or aut n paca

Ear parent 90d of coronary nev osoaso

00,4235

‘The findings show an increased risk, as

expected, for all variables except body

mass index, which shows a trend in the

expected direction only in women.

Multiple logistie analyses were done

to estimate RR of death in the fitness

categories while adjusting for potential

confounding. The dependent measure

‘was all-cause mortality and the model

included physical fitness and all vari-

ables in Table 3. All variables were in-

cluded, although overweight for height

in both men and women and parental

history of coronary heart disease (CHD)

in women were not statistically signifi-

cantly associated with mortality in uni-

variate analyses. The RRs (95% Cl) of,

Jow physical fitness for all-cause mortal-

ity foreach quintile (to Q4) compared

with the most-fit quintile were as fol-

lows: Q1=1.58 (1.23 to 1.89), Q2= 1.08

(0.81 to 1.80), Q8=1.12 (0.89 to 1.40),

and Q4 = 1.08 (0.81 to 1.28) for men; and

QL= 1.98 (1.18 to 3.47), Q2=1.45 (0.80

to 2.62), Q3=1.07 (0.55 to 2.08), and

07 (0.55 to 2.23) for women, A

SAMA, Novertoer 3, 1989— Vo! 262, No. 17

‘more pronounced dose-response gradi-

tent was seen when length of follow-up

(as a continuous variable) was added to

the model, Relative risks (95% CI) for

the four less-ft quintiles relative to the

most-fit quintile were as follows:

QL = 1.82.88 to2.40), Q2=1.38.(.0t0

1.78), Q3=1.29 (0.97 to 1-70), and

Qk=1.06 (0,78 to 1.44) for men and

Q1~3.02 4.89 to 11.04), Q2=3.01 4.05

to 8.65), Q8=2.06 (0.66 to 6.22), and

Q1= 1.55 (0.49 to 4.91) for women, Sev-

eral interaetion terms among the inde-

pendent variables were tested, and the

assumption of no interaction on a multi-

plicative scale was not violated,

‘Subclinical disease could eause poor

performance on the treadmill and also

lead to elevated death rates in patients

presumed to be healthy at baseline.

Mortality rates in both short- and long

term follow-up were examined to test

the hypothesis that preexisting disease

was confounding the relationship be-

tween fitness and mortality. Logistie

regression analyses were done for two

{f0p) and 9120 women (boron) it Aerob

Center Longtusinal Std, bysysica! finess que

‘es a5 delomined by maximal Teas exerise

teste

subgroups.as follows: the first 3 years of

follow-up and for extended follow-ap af-

ter 3 years. The dependent measure

was all-cause mortality. Low

again was defined as the first quintile of

the fitness distribution. Other indepen-

dent variables in the analyses were

those in Table 8, to control for possible

confounding. Adjusted RRs for all

cause mortality in low-fit men were as

follows: follow-up less than or equal to

years, 1,60 (95% CI, 1.18 to 2.16); and

follow-up greater than 3 years, 1.45

(95% CI, 1.08 to 1.96). Corresponding

values for women were as follows: less

than or equal to 3 years, 1.47 (95% Cl,

0.14 to 2.94); and greater than 3 years,

3.00 (95% CI, 1.06 08.61), The elevated

RR in later follow-up suggests that the

relationship between fitness and mor-

tality isnot likely to be due entirely to

confounding by subclinical disease.

‘Age-specific, all-cause mortality

rales actoss ‘fitness categories are

shown in Fig 1. ‘The upper panel pre-

sents data for men, and the lower, for

women, Inboth analyses, the decline in

death rates with higher levels of fitness

‘is more pronouneed in the older individ-

uals. The small number of deaths in the

younger women leads to unstable esti-

mates of the death rate in this group.

‘Table 4 shows cause-specific death

rates by fitness categories in men and

women, The fitness quintiles were col-

Japsed into three groups for these ana-

lyse due to smaller numbers of deaths

Physical Fitness and Mortaliy—Saretal 2397

“eble 4.—Age-hajisted Cause-Spectic Ova Rates per 10000 Person-Years of Follow-up (1970 10 1965) by Physical Finess Groups n Men and Women in the

‘Aerobics Cones Longtudnal Stay

a onthe at

= td et

nhingcasn tonite teas st eter

me

a ew! esas sa -s2

Se raeas 3

aaa Pa

a rms fet as n02.-07

or

a we Pil

Scanian

ee 1 wes “ese 7 a

ae

Ee, 008) = ese “8-33

abe tS) 5 ue ee oe

we eee 7 is $a aw

sas Seton 7 ts ee rot

SS on oan ere renee Cao Sores Tone eT TOOT

w a we oo! name

& ne, aaa santos

gb a Nore § om

: - ve, ey EY A

1 le, — i } 7

ey eA g2 z ge an

‘ o samen [pie wae

econ

7 : .

t ro tones é ty aoe

i aoae . 1

: [zn — i ;

i : i ie

vol Ps j y a

7 J coun / eee;

“Toes Te om 0 ashes Pi ran

ws ay

Fanos Cnooo) Firesscatgory

Fig 2—Relative risks of al-cause mentaly in 3120 women inthe Aerobics Center Longitudinal Stay, by

‘hysical fness catorae ad ood preeeue (A, eum chotaetr! level (8), serum ghcose iva ().

‘Smoking habits (0) Body mass index (E) and parental history of coronary heart dscese (F). Each Dar

‘epracese the rete isk based on oge-edjustus, all cause death rates per 10.00 person-years ct olow=

LUnwthtn elaiverskoftne ont ight callaet at 1.0. Numbers entopotthe bars aretrealrcase death rloe

‘er 10000 person‘ears of folow-up for each call. The number of deaths fh each cel is shown Inthe

paraleograms|

in the specific causes. There are few strong gradient across fitness groups in presented in Figs 2 and 8. In these ste-

deaths for the specific causes in women, _bothmen and women, while none isseen _reograms, the back-left cell shows the

which leads to unstable estimates of for other causes of death. RR for ‘the presumed highest-risk

rates; these results should be inter- The RRs for all-cause mortality by group (eg, ow fit and high systolic blood

preted cautiously. Death rates for ear- cross-tabulations of fitness groups and pressure). The lowest risk group (refer-

diovascular disease and cancer show a other elinical and life-style variables are ent) is in the front-right cell of the fig-

2398 JAMA, Novernber 3, 1988—Vol 262, No.17 Pysicel Finest and Mortlty —lai eta)

g 0” Ne otbeats

a

4° dea

& 2%

| Cee ie resrgnise

3 [is bobo,

aches) one

Freeaconmey

° e r

s of Sfenre

Be No olDetns ro.stoeere 4 o.tbeste

a ase i Seay

3 a 3) AERA 5 *

ay fe :

ae ou 7 = Panty Hy Deh

com eo ee ret AE ttn

ARTE Fines Category —

fusca

Fig 3.—Ralatin ric of allcauso mertaly in 10.224 man in tha Aarobics Canter Longtudieal Study. by

[Physical tiness categores and bcos pressure (A), serum cholesterol ove (B), sam glucce lave! (C),

Smoking nabts (0), Booy mass index

represents

afd patent history of coronary heart csease (F). Each Bat

wen the rete iskof the tront-ght call set at 0, Numbers on top ote bar are the slave death ates

per 10000 porzonyoare of fellow-up for each oe. The numéer of athe in each cal i shown in the

paraleiograms,

ures. Cutoff points for the eliniea! and

behavioral risk factors in these analyses

were established somewhat arbitrarily,

80 as to provide an adequate number of

person-years in each cell for analysis.

Increased risk of death in low-fit men

andwomenis clearly illustrated in these

stereograms, and this pattern generally

holds across risk strata for the other

variables. In several cases, notably ste-

reograms for men onblood pressure and

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5807)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (346)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Reflective Practice and Professional Development in Psychotherapy (Poornima Bhola, Chetna Duggal, Rathna Isaac)Document369 pagesReflective Practice and Professional Development in Psychotherapy (Poornima Bhola, Chetna Duggal, Rathna Isaac)12traderNo ratings yet

- Democracy Index 2022 Frontline Democracy and The Battle For Ukraine (The Economist Intelligence Unit) (Z-Library) - 49-50Document2 pagesDemocracy Index 2022 Frontline Democracy and The Battle For Ukraine (The Economist Intelligence Unit) (Z-Library) - 49-5012traderNo ratings yet

- Democracy Index 2022 Frontline Democracy and The Battle For Ukraine (The Economist Intelligence Unit) (Z-Library) - 13-14Document2 pagesDemocracy Index 2022 Frontline Democracy and The Battle For Ukraine (The Economist Intelligence Unit) (Z-Library) - 13-1412traderNo ratings yet

- Democracy Index 2022 Frontline Democracy and The Battle For Ukraine (The Economist Intelligence Unit) (Z-Library) - 29-30Document2 pagesDemocracy Index 2022 Frontline Democracy and The Battle For Ukraine (The Economist Intelligence Unit) (Z-Library) - 29-3012traderNo ratings yet

- Democracy Index 2022 Frontline Democracy and The Battle For Ukraine (The Economist Intelligence Unit) (Z-Library) - 31-32Document2 pagesDemocracy Index 2022 Frontline Democracy and The Battle For Ukraine (The Economist Intelligence Unit) (Z-Library) - 31-3212traderNo ratings yet

- Democracy Index 2022 Frontline Democracy and The Battle For Ukraine (The Economist Intelligence Unit) (Z-Library) - 1-2Document2 pagesDemocracy Index 2022 Frontline Democracy and The Battle For Ukraine (The Economist Intelligence Unit) (Z-Library) - 1-212traderNo ratings yet

- Besomi M. Et Al. Running Motivations Within Different Populations of Chilean Urban RunnersDocument5 pagesBesomi M. Et Al. Running Motivations Within Different Populations of Chilean Urban Runners12traderNo ratings yet

- Democracy Index 2022 Frontline Democracy and The Battle For Ukraine (The Economist Intelligence Unit) (Z-Library) - 7-8Document2 pagesDemocracy Index 2022 Frontline Democracy and The Battle For Ukraine (The Economist Intelligence Unit) (Z-Library) - 7-812traderNo ratings yet

- The Cognitive Philosophy of ReflectionDocument24 pagesThe Cognitive Philosophy of Reflection12traderNo ratings yet

- On Reflection (Hilary Kornblith)Document187 pagesOn Reflection (Hilary Kornblith)12traderNo ratings yet