Professional Documents

Culture Documents

C2 C3 General Provisions NatureEffects

C2 C3 General Provisions NatureEffects

Uploaded by

Bianca Jampil0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views31 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views31 pagesC2 C3 General Provisions NatureEffects

C2 C3 General Provisions NatureEffects

Uploaded by

Bianca JampilCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 31

TITLE |

OBLIGATIONS

(Arts. 1156-1304, Civil Code.)

Chapter 1

GENERAL PROVISIONS

ARTICLE 1156. An, obligation is a juridical

necessity to give, to do or not to do. (n)

Meaning of obligation.

The term obligation is derived from the Latin word

obligatio which means fying or binding.

It isa tie or bond recognized by law by virtue of which

one is bound in favor of another to render something — and

this may consist in giving a thing, doing a certain act, or not

doing a certain act.

Civil Code definition.

Article 1156 gives the Civil Code definition of

obligation, in its passive aspect. It merely stresses the duty

under the law of the debtor or obligor (he who has the duty

of giving doing, or not doing) when it speaks of obligation

as a juridical necessity.

18 THE LAW ON OBLIGATIONS AND Art. 1156.

CONTRACTS

Meaning of juridical necessity.

Obligation is a juridical necessity because in case of

noncompliance, the courts of justice may be called upon by

the aggrieved party to enforce its fulfillment or, in’ default

thereof, the economic value that it represents. In a proper

case, the debtor or obligor may also be made liable for

dainages, which represents the sum of money given as a

compensation for the injury or harm suffered by the creditor

or obligee (he who has the right to the performance of the

obligation) for the violation of his rights.

In other words, the debtor must comply with his obli-

gation whether he likes it or not; otherwise, his failure will

be visited with some harmful or undesirable consequences.

If obligations were not made enforceable, then people can

disregard them with impunity. There are, however, obliga-

tions that cannot be enforced because they are not recog-

nized by law as binding.

Nature of obligations under

the Civil Code.

Obligations which give to the creditor or obligee a

right under the law to enforce their performance in courts

of justice are known as civil obligations. They are to be dis-

tinguished from natural obligations, which, not being based.

on positive law but on equity and natural law, do not grant

a right of action to enforce their performance although in

case of voluntary fulfillment by the debtor, the latter may

‘not recover what has been delivered or rendered by reason

: thereof. (Art. 1423,)

Natural obligations are discussed under the Title deal-

ing with “Natural Obligations.” (Title III, Arts. 1423-1430.)

{Unless otherwise indicated, refers to article in the Civil Code.

Art. 1156 GENERAL PROVISIONS 9

Essential requisites of an obligation.

Every obligation has four (4) essential requisites,

namely:

(1) A passive subject (called debtor or obligor). — the

person who is bound to the fulfillment of the obligation; he

who has a duty;

(2) An active subject (called creditor or obligee). —

the person who is entitled to demand the fulfillment of the

obligation; he who has a right;

(3) Object or prestation (subject matter of the obliga-

tion). — the conduct required to be observed by the debtor.

It may consist in giving, doing, or not doing. Without the

prestation, there is nothing to perform. Ln bilateral obliga-

tions (see Art. 1191.), the parties are reciprocally debtors and

creditors; and

(4) A juridical or legal tie (also called efficient cause).

~~ that which binds or connects the parties to the obligation.

The tie in an obligation can easily be determined by knowing

the source of the obligation. (Art. 1157.) ~

EXAMPLE:

Under a building contract, X bound himself to build a

house for Y for P1,000,000.

Here, X is the passive subject, Y is the active subject,

the building of the house is the object or prestation, and the

agreement or contract, which is the source of the obligation,

is the juridical tie.

Suppose X had already constructed the house and it

was the agreement that Y would pay X after the construction

is finished, X then becomes the active subject and Y, the

passive subject,

Form of obligations.

The forn of ar obligation refers to the manner in which

an obligation is manifested or incurred. It may be oral, or in

writing, or partly oral and partly in writing. —

20 ‘THE LAW ON OBLIGATIONS AND. Art, 1156

CONTRACTS:

(1) As a general rule, the law does not require any

form in obligations arising from contracts for their validity

or binding force. (see Art. 1356.)

(2) Obligations arising from other sources (Art. 1157.)

do not have any form at all.

Obligation, right, and wrong distinguished.

(1) Obligation is the act or performance which the law

will enforce.

(2) Right, on the other hand, is the power which a

person has under the law, to demand from another any ~

Pprestation.

(3) A wrong {cause of action), according to its legal

meaning, is an act or omission of one party in violation of

the legal right or rights (ie., recognized by law) of another.

In law, the term injury is also used to refer to the wrongful

violation of the legal right of another.

The essential elements of a legal wrong or injury are:

(a) a legal right in favor of a person (creditor /

obligee/ plaintiff);

(b) a correlative legal obligation on the part of

another (debtor / obligor /defendant); to respect or not

to violate said right; and

(c) an act or omission by the latter in violation

of said right with resulting injury or damage to the

former.

An obligation on the part of a person cannot exist

without a corresponding right in favor of another, and vice

versa. A wrong or cause of action only arises at the moment

a right has been transgressed or violated.

EXAMPLE:

In the preceding example, Y has the legal right to have

his house constructed by X who has the correlative legal

Art 1156 GENERAL PROVISIONS 21

obligation to build the house of Y under their contract. X

has the right to be paid the agreed compensation provided

the house is built according to the terms and conditions of

the contract. The failure of either party to comply with such

terms and conditions gives the other a cause of action for

the enforcement of his right and/or recovery of indemnity

for the loss or damage caused to him for the violation of his

sight.

Kinds of obligation according

to the subject matter.

From the viewpoint of the subject matter, obligation

may be either real or personal.

(1) Real obligation (obligation to give) is that in which

the subject matter is a thing which the obligor must deliver

to the obligee.

EXAMPLE:

X (e.g, seller) binds himself to deliver a piano to Y

(buyer).

(2) Personal obligation (obligation to do or not to do) is

that in which the subject matter is.an act to be done or not to

be done. There are two (2) kinds of personal obligation:

(a) Positive personal obligation or obligation to do

or to render service. (see Art. 1167.)

EXAMPLE:

X binds himself to repair the piano of Y.

(b) Negative personal obligation is obligation not

to do (which naturally includes obligations “not to

tive”). (see Art. 1168.)

2 ‘THE LAW ON OBLIGATIONS AND Art. 1157

CONTRACTS

EXAMPLE:

X obliges himself not to build a fence on a certain

portion of his lot in favor of Y who is entitled to a right of

way over said lot.

ART. 1157. Obligations arise from:

(1) Law;

(2) Contracts;

(3) Quasi-contracts; .

(4) Acts or omissions punished by law;

and

(5) Quasi-delicts. (1089a)

Sources of obligations.

The sources of obligations are enumerated below:

(1) Law. — when they are imposed by law itself.

EXAMPLES:

Obligation to pay taxes; obligation to support one’s

family, (Art. 291.)

(2) Contracts. — when they arise from the stipulation

of the parties. (Art. 1306.)

EXAMPLE:

The obligation to repay a_loan or indebtedness by

virtue of an agreement.

(3) Quasi-contracts. when they arise from lawful,

voluntary and unilateral acts which are enforceable to the

end thatno one shall be unjustly enriched or benefited at the

expense of another, (Art. 2142.) In a sense, these obligations

may be considered as arising from law.

Art 1157 GENERAL PROVISIONS 23

T:XAMPLE:

The obligation to retum money paid by- mistake or

which is not due. (Art. 2154.)

(4) Crises or acts or omissions punished by law. — when

they arise from civil liability which is the consequence of a-

criminal offense. (Art. 1261.)

EXAMPLE:

The obligation of a thief to return the car stolen by him;

the duty of a killer to indemnify the heirs of his victim.

(5) Quasi-delicts or torts. -- when they arise from

damage caused to another through an act or omission, there

being fault or negligence, but no contractual relation exists

between the parties, (Art. 2176.)

EXAMPLES:

The obligation of.the head of a family that lives in a

building or a part thereof to answer for damages caused

by things thrown or falling from the same (Art. 2193.);

the obligation of the possessor of an animal to pay for the

damage which it may have caused. (Art. 2183.)

Sources classified.

The law enumerates five (5) sources of obligations.

They may be classified as follows:

(1) Those emanating from law; and

(2) Those emanating from private acts which may be

further subdivided into:

(a) Those arising from licit acts, in the case of

contracts and quasi-contracts (infra.); and

(b) Those arising from illicit acts, which may be

either punishable in the case of delicts or crimes, or not

punishable in the case of quasi-delicts or torts. (infra.)

24 THE LAW ON OBLIGATIONS AND Art. 1158

CONTRACTS

Actually, there are only two (2) sources: law and con-

tracts, because obligations arising from quasi-contracts,

delicts, and quasi-delicts are really imposed by law. (see

Leung Ben vs. O'Brien, 38 Phil. 182.)

ART. 1158. Obligations derived from

law are not presumed. Only those expressly

determined in this Code or in special laws are

demandable, and shall be regulated by the

precepts of the law which establishes them;

and as to what has not been foreseen, by the

provisions of this Book. (1090)

Legal obligations.

Article 1168 refers to legal obligations or obligations

arising from law. They are not presumed because they

are considered a burden upon the obligor. They are the

exception, not the rule. To be demandable, they must be

clearly set forth in the law, ie, the Civil Code or special

laws. Thus: oO

(1) An employer has no obligation to furnish free

jegal assistance to his employees because no law requires

this, and therefore, an employee may not recover from his

employer the amount he may have paid a lawyer hired

by him to recover damages caused to said employee by a

stranger or strangers while in the performance of his duties.

(De la Cruz vs. Northern Theatrical Enterprises, 95 Phil.

739.)

Q) A private school has no legal obligation to provide

clothing allowance to its teachers because there is no law

which imposes this obligation upon schools. But a person

who wins money in gambling has the duty to return his

winnings to the loser. This obligation is provided by law.

(Art, 2014.)

Under Article 1158, special iaws refer to all other laws

not contained in the Civil Code. Examples of such laws are

Art 1189 GENERAL PROVISIONS 25

Corporation Code, Negotiable Instruments Law, Insurance

Code, National Internal - Revenue Code, Revised Penal

Code, Labor Code, etc.

ART. 1159. Obligations arising from con-

tracts have the force of law between the con-

tracting parties and should be complied with

in good faith. (10914)

Contractual obligations.

The above article speaks of contractual obligations or

obligations arising from contracts or voluntary agreements.

li presupposes that the contracts entered into are valid and

enforceable.

A contract is a meeting of minds between two (2) per-

sons whereby one binds himself, with respect to the other,

to give something or to render some service. (Art. 1305.)

(1) Binding force. ~ Obligations arising from contracts

have the force of law between the contracting parties, ie.,

they have same binding effect of obligations imposed by

laws. This does not mean, however, that contract is superior

to the law. As a source of enforceable obligation, contract

must be valid and it cannot be valid if itis against the law.

(2) Requirement ofa valid contract. ~~ Acontract is valid

(assuming all the essential elements are present; Art. 1318.)

if it is not contrary to Jaw, morals, good customs, public

order, and public policy. ft is invalid or void if it is contrary

to law, morals, good customs, public order, or public policy.

(Art, 1306.)

In the eyes of the law,-a void contract does not exist.

(Art. 1409,) Consequently, no obligations will arise, A

contract may be valid but cannot be enforced. This is true in

the case of unenforceable contracts. (see Arts. 1517, 1403.)

(3) Breach of contract. — A contract may be breached or

violated by a party in whole or in part. A breach of contract

26 THE LAW ON OBLIGATIONS AND. Art. 1160

CONTRACTS

takes place when a party fails or refuses to comply, without

legal reason or justification, with his obligation under the

contract as promised,

Compliance in good faith.

Compliance in good faith means compliance or perfor-

mance in accordance with the stipulations or terms of the

contract or agreement. Sincerity and honesty must be ob-

served to prevent one party from taking unfair advantage

over the other.

Non-compliance by a party with his legitimate obliga-

tions after receiving the benefits of a contract would consti-

tute unjust enrichment on his part.

EXAMPLES:

(1) If S agrees to sell his house to B and B agrees

to buy the house of S, voluntarily and willingly, then they

are bound by the terms of their contract and neither party

may, upon his own will, and without any justifiable reason,

withdraw from the contract or escape from his obligations

thereunder.

That which is agreed upon in the contract is the law

between S and B and must be complied with in good faith.

(2) Acontract whereby S will kill B in consideration,

of P1,000 to be paid by C, is void and non-existent because

killing a person is contrary to law. Likewise, an agreement

whereby S will render domestic service gratuitously until

his loan to B is paid, is void as being contrary to law and

morals. (see Art. 1689; De los Reyes vs. Alejado, 16 Phil. 499.)

In both cases, S$ has no obligation to comply with his

agreements.

ART. 1160. Obligations derived from quasi-

contracts shall be subject to the provisions of

Chapter 1, Title XVI of this Book. {n)

Art, 160 GENERAL PROVISIONS 7

Quasi-contractual obligations.

Article 1160 treats of obligations arising from quasi-

contracts or contracts implied in law.

A quasi-contract is that juridical relation resulting from

lawful, voluntary and unilateral acts by virtue of which

the parties become bound to each other to the end that no

one will be unjustly enriched or benefited at the expense of

another, (Art. 2142.)

[Lis not properly a contract at all. In contract, there is

a meeting of the minds or consent (see Arts, 1318, 1319.);

the parties must have deliberately entered into a formal

agreement. In a quasi-contract, there is no consent but the

same is supplied by fiction of law. Jn other words, the law

considers the parties as’ having entered into a contract,

although they have not actually done so, and irrespective of

their intention, to prevent injustice or the unjust enrichment *

of a person at the expense of another.

Kinds of quasi-contracts.

the principal kinds of quasi-contracts are negotiorum

weatio and soltitio indebiti.

(1) Negotioruit gestio is the voluntary management of

the property or affairs of another without the knowledge or

consent of the latter. (Art. 2144.)

UXAMPLE:

X went to Baguio with his family without leaving

someboely to look after his house in Manila, While in Baguio,

a big fire broke out near the house of X. Through the effort of

Y, a neighbor, the house of X was saved from being burned.

Y, however, incurred expenses.

In this case, X has the obligation to reimburse Y for said

expenses, although he did not factually give his consent to

the act of Y in saving his house, on the principle of quasi-

contract.

28 ‘THE LAW ON OBLIGATIONS AND Art. 1161

CONTRACIS

(2).Solutio_indebiti is the juridical relation which is

created when something is received when there is no right

to demand it and it was unduly delivered through mistake.

(Art. 2154.) The requisites are:

(a) There is no right to receive the thing deliv-

ered; and

(b) The thing was delivered through mistake.

EXAMPLE:

D owes C P1,000. If D paid T believing that T was

authorized to receive payment for C, the obligation to return

on the part of T arises. If D paid € P2,000 by mistake, C must

return the excess of P1,000.

(3) Other examples of quasi-contracts. — They are

provided in Article 2164 to Article 2175 of the Civil Code, -

The cases that have been classified as quasi-contracts are of

infinite variety, and when for some reason recovery cannot

be had on a true contract, recovery may be allowed on the

basis of a quasi-contract.

EXAMPLE:

S, seller of goat’s milk leaves milk at the house of B

each morning. B uses the milk and places the empty bottles

on the porch. After one (1) week, $ asks payment for the

milk delivered,

* Here, an impliéd contract is understood to have

been entered into by the very acts of S and B, creating an

obligation on the part of B to pay the reasonable value of

the milk, otherwise, B would be unjustly benefited at the

expense of S,

ART. 1161. Civil obligations arising from

criminal offenses shall be governed by the

penal laws, subject to the provisions of article

2177, and of the pertinent provisions of Chapter”

Avi Hot GENERAL PROVISIONS 29

2, Preliminary Title, on Human Relations, and

of Title XVII of this Book, regulating damages.

(1092a)

Civil liability arising from crimes

or delicts.

‘This article deals with civil liability for damages arising

from crimes or delicts, (Art. 1157[4].)

(1) Oftentimes, the commission of a crime causes

not only moral evil but also material damage. From this

principle, the rule has been established that every person

criminally liable for an act or omission is also civilly liable

for damages. (Art. 100, Revised Penal Code.)

(2) in crimes, however, which cause no material

damage (like contempt, insults to persons in authority,

sambling, violations of traffic regulations, etc.), there is no

civil liability to be enforced. But a person not criminally

responsible may still be liable civilly (Art. 29; Sec. 2[c], Rule

111, Rules of Court.), such as failure to pay a contractual debt;

causing damage to another's property without malicious or

criminal intent or negligence, etc.

Scope of civil liability.

The extent of the civil liability for damages arising

from crimes is governed by the Revised Penal Code and the

Civil Code. This civil liability includes:

(1) Restitution;

(2) Reparation for the damage caused; and

(3) Indemnification for consequential damages. (Art.

104, Revised Penal Code.)

VXAMPLE:

X stole the car of Y. If X is convicted, the court will

order X: (1) to return the car or to pay its value if it was

lost or destroyed; (2) to pay for any damage caused to the

a

a0 THE LAW ON OBLIGATIONS AND Art. 1162

CONTRACTS

car; and (3) to pay such other damages suifered by Y as a

consequence of the crime.

ART. 1162. Obligations derived from quasi-

delicts shall be governed by the provisions

of Chapter 2, Title XVI of this Book, and by

special laws. (1093a)

Obligations arising from

quasi-delicts. .

The above provision treats of obligations arising from

quasi-delicts or torts. (see Arts. 2176 to 2194.)

A quasi-delict is an act or omission by a person (tort-

feasor) which causes damage to another in his person, pro-

perty, or rights giving rise to an obligation to pay for the

damage done, there being fault or negligence but there is no

pre-existing contractual relation between the parties. (Art.

2176.)

Requisites of quasi-delict.

Before a person can be held liable for quasi-delict, thé

following requisites must be present:

(1) There must be an act or omission;

(2) There must be fault or negligence;

(3) , There must be damage caused;

(4) There must be a direct relation or connection *

of cause and effect between the act or omission and the

damage; and

(3) There is no pre-existing contractual relation

between the parties.

EXAMPLE:

While playing softball with his friends, X broke the

window glass of Y, his neighbor. The accident would not

Ant 1182 GENERAL PROVISIONS 31

have happened had they played a little farther from the

house of ¥.

In this case, X is under obligation to pay the damage

caused to ¥ by his act although there is no pre-existing

contractual relation between them because he is guilty of

fault or negligence.

Crime distinguished from quasi-delict.

The following are the distinctions:

(1) In crime, there is criminal or malicious intent

or criminal negligence, while in quasi-delict, there is only

negligence;

(2) In crime, the purpose is punishment, while in

quasi-delict, indemnification of the offended party;

(3) Crime affects public interest, while quasi-delict

concerns private interest;

{4) Incrime, there are generally two liabilities; crimi-

nal and civil, while in quasi-delict, there is only civil liabil-

ity;

(5) Criminal liability can not be compromised or

settled by the parties themselves, while the liability for

quasi-delict can be compromised as any other civil liability;

and .

(6) Incrime, the guilt of the accused must be proved

beyond reasonable doubt,: while in quasi-delict, the fault

or negligence of the defendant need only be proved by

preponderance (i.¢., superior or greater weight) of evidence.

— 000 —

*The evidence must be very clear and convincing as will engender belief in

an unprejudiced mind that the accused is really guilty.

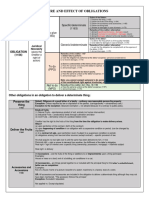

Chapter 2

NATURE AND EFFECT

OF OBLIGATIONS

ART. 1163, Every person obliged to give

something is also obliged to take care of it

with the proper diligence of a good father of

a family, unless the law or the stipulation of

the parties requires another standard of care.

(1094a)

Meaning of specific or determinate thing.

The above provision refers to an obligation specific or

determinate thing.

A thing is said to be specific or determinate particularly

designated or physically segregated others of the same

class. (Art. 1459.)

EXAMPLES:

(1) the watch Iam wearing.

(2) the car sold by X.

(3) my dog named “Terror.”

(4) the house at the corner of Rizal and del Pilar

Streets,

(5) the Toyota car with Plate No. AAV 316 (2008).

(6) _ this cavan of rice.

(7) the money I gave you.

Me

At 116d NATURE AND EFFECY OF 35

OBLIGATIONS

Meaning of generic or indeterminate thing.

A thing is generic or indeterminate when it refers only to

a class or genus to which it pertains and cannot be pointed

out with particularity.

UXAMPLES:

(1) a Bulova calendar watch.

(2) the sum of P1,000.

(3) a 1995 Toyota can

(4) acavan of rice.

(5) a police dog.

Specific thing and generic thing

distinguished.

(1) A determinate thing is identified by its individu-

ality, The debtor cannot substitute it with another although

the latter is of the same kind and quality without the con-

sent of the creditor, (Art, 1244.)

() A yenerie thing is identified only by its specie.

The debtor can give anything of the same class as long as it

js of the same kind

DXAMPLES

(1) 1S's obligation is to deliver to Ba Bulova calendar

watch, § can deliver any watch as long as it is a Bulova with

calendar

Bul it’s obligationts to deliver to B a particular watch,

the one S is wearing, $ cannot substitute it with another

watch without B’s consent nor can B require S to deliver

another watch without 5’s consent although it may be of the

same Kind and vatue. (see Arts, 1244, 1246.)

(2) I1S’s obligation is to deliver to B onc of his cars, the

object refers to a class which in itself is determinate.

36 THE LAW ON OBLIGATIONS AND Art. 1163

CONTRACTS,

Here, the particular thing to be delivered is determin-

able without the need of a new contract between the parties

(see Art. 1349.); it becomes determinate upon its delivery,

Duties of debtor in obligation to give

a determinate thing.

They are:

(1) Preserve the thing. — In obligations to give (real

obligations), the obligor has the incidental duty to take care

of the thing due with the diligence of a good father of a

family pending delivery.

(a) Diligence of a good father of a family. — The

phrase has been equated with ordinary care or that

diligence which an average (a reasonably prudent)

person exercises over his own property.

(b) Another standard of care. ~ However, if the law

or the stipulation of the parties provides for another

standard of care (slight or extraordinary diligence),

said law or stipulation must prevail, (Art. 1163.)

Under the law, for instance, a common carrier

{person or company engaged in the transportation

of persons and/or cargoes) is “bound to carry the

passengers safely as far as human care and foresight

can provide, using utmost (iz, extraordinary)

diligence of very cautious persons, with a due regard

for all the circumstances.” (Art. 1755.) In case of

accident, therefore, the common carrier will be liable if

it exercised only ordinary diligence or the diligence of

a good father of a family.

The parties may agree upon diligence which is

more or less than that of a good father of a family but it

is contrary to public policy (see Art. 1306.) to stipulate

for absolute exemption from liability of the obligor

for any fault or negligence on his part. (see Arts. 1173,

1174.)

Ant Hat NATURE AND EFFECT OF 37

OBLIGATIONS

(c) Factors to be considered. — The diligence

required necessarily depends upon the nature of the

obligation and corresponds with the circumstances of

the person, of the time, and of the place. (Art. 1173.) It

is not necessarily the standard of care one always uses

in the protection of his property. As a general rule, the

debtor is not liable if his failure to preserve the thing

is not due to his fault or negligence but to fortuitous

events or force majeure. (Art. 1174.)

EXAMPLE:

S binds himself to deliver a specific horse to B on a

certain date.

Pending delivery, S has the additional or accessory

duty to take care of the horse with the diligence of a good

father of a family, like feeding the horse regularly, keeping

it in a safe place, etc. In other words, S must exercise that

diligence which he would exercise over another horse

belonging to him and which he is not under obligation to

deliver to B.

But S cannot relieve himself from liability in case

of loss by claiming that he exercised the same degree of

care toward the horse as he would toward his own, if such

care is less than that required by the circumstances. If the

horse dies or is lost or becomes sick as a consequence of S's

failure to exercise proper diligence, he shall be liable to B

for damages.

The accessory obligation of $ to take care of the horse

is demandable even if no mention thereof is made in the

contract.

(d) Reason for debtor’s obligation. — The debtor

must exercise diligence to insure that the thing to be

delivered would subsist in the same condition as it

was when the obligation was contracted. Without the

accessory duty to take care of the thing, the debtor

would be able to afford being negligent and he would

3H Hts LAW ON OBLIGATIONS AND Art, 1164

CONTRACTS:

not be liable even if the property is lost or destroyed,

thus rendering illusory the obligation to give (8

Manresa, 35-37.);

(2) Deliver the fruits of the thing. — This is discussed

under Article 1164;

(3) Deliver the accessions and accessories. —- This is

discussed under Article 1166;

(4) Deliver the thing itself. — (Arts, 1163, 1233, 1244; as

to kinds of delivery, see Arts. 1497 to 1501.); and

(5). Answer for damages in a of non-fulfillinent or

breach. — this is discussed under Article 1170.

Se

Duties of debtor in obligation to deliver =

a generic thing.

They are:

(1) To deliver a thing which is of the quality intended

by the parties taking into consideration the Purpose of the

obligation and other circumstances (see Art. 1246.); and

(2) To be liable for damages in case of fraud, negli-

gence, or delay, in the performance of his obligation, or con-

travention of the tenor thereof. (sce Art. 1170.}

ART. 1164. The creditor has a right to the

fruits of the thing from the time the obligation

to deliver it arises. However, he shall acquire

no real right over it until the same has been

delivered to him. (1095)

Different kinds of fruits.

The -fruits mentioned by the law refer to natural,

industrial, and civil fruits.

(1) Natural fruits ave the spontaneous products of the

soil, and the young and other products of animals.

‘arise

Art. 1164 39

EXAMPLES:

Grass; all trees and plants on lands produced without

the intervention of human labor.

(2) Industrial fruits are those produced by lands of

any kind through cultivation or labor.

EXAMPLES:

Sugar cane; vegetables; rice: and all products of lands

brought about by reason of human labor.

(3) Civil fruits are those derived by virtue of ajuridical

relation.

EXAMPLES:

Rents of buildings, price of leases of lands and other

property and the amount of perpetual or life annuities or

other similar income, (Art. 442.)

Right of creditor to the fruits.

The creditor is entitled to the fruits of the thing to be

delivered from the time the obligation to make delivery

The intention of the law is te protect the interest of

the obligee should the obligor commit delay, purposely or

otherwise, in the fulfiUiment of his obligation,

When obligation to deliver fruits

arises.

(1) Generally, the obligation to deliver the thing due

and, consequently, the fruits thereof, if any, arises from the

time of the “perfection of the contract.” Perfection, in this

case, refers to. the birth of the contract or to the meeting of

the minds between the parties. (Arts, 1305, 1315, 1319.)

(2) Tf the obligation is subject to a suspensive

condition or period (Arts. 1179, 1189, 1193.), it arises upon

40 THE LAW ON OBLIGATIONS AND Art. 1164

CONTRACTS

the fulfillment of the condition or arrival of the term.

However, the parties may make a stipulation to the contrary

as regards the right of the creclitor to the fruits of the thing.

(3) Ina contract of sale, the obligation arises from the

perfection of the contract even if the obligation is subject

to a suspensive condition or a suspensive period where the

price has been paid.

(4) In obligations to give arising from law, quasi-con-

tracts, delicts, and quasi-delicts, the time of performance is

determined by the specific provisions of the law applicable.

EXAMPLE:

$ sold his horse to B for P15,000. No date or condition

was stipulated for the delivery of the horse. While still in the

possession of S, the horse gave birth to a colt.

Who has a right to the colt?

In a contract of sale “all the fruits shall pertain to the

vendee from the day on which the contract was perfected.”

(Ast. 1537, 2nd par.) Hence, B is entitled to the colt. This holds

true even if the delivery is subject to a suspensive condition

{e.g., upon the demand of B) or a suspensive period (e.g,

next month) if B has paid the price.

But S has a right to the colt if it was born before the

obligation to deliver the horse has arisen (Art. 1164.) and B

has not yet ‘paid the purchase price. In this case, upon the

fulfillment of the condition or the arrival of the period, S

does not have to give the colt and B is not obliged to pay

legal interest on the price since the colt and the interest are

deemed to have been mutually compensated. (see Att. 1187.)

Meaning of personal right and real right.

(1) Personal right is the right or power of a person

(creditor) to demand from another (debtor), as a definite

passive subject, the fulfillment of the latter’s obligation to

give, to do, or not-to do.

Aut 16d NATURE AND: ERFECT OF 41

OBLIGATIONS

(2) Real right is the right or interest of a person over

a specific thing (like ownership, possession, mortgage).

without a definite passive subject against whom the right

may be personally enforced,

Personal right and real right distinguished.

(1) In personal right there is a definite active subject

and a definite passive subject, while in real right, there is

only a definite active subject without any definite passive

subject. (see Art. 1156.)

(2) A personal right is, therefore, binding or enforce-

able only against a particular person, while a real right is

directed against the whole world. (see next example.)

EXAMPLE:

X is the owner of a parcel of land under a torrens

title registered in his name in the Registry of Property. His

ownership is a real right directed against everybody. There

is no definite passive subject.

If the land is claimed by Y who takes possession, X

has a personal right to recover from Y, as a definite passive

subject, the property.

If the same land is mortgaged by X to Z, the mortgage,

if duly registered, is binding against third persons. A

purchaser buys the land subject to mortgage which is a real

tight. .

Ownership acquired by delivery.

Ownership and other real rights over property are

acquired and transmitted in consequence of certain contracts

by tradition (Art. 712.) or delivery. In sale, for example, mere

Agreement on the terms thereof does not effect transfer

of ownership of the thing sold in the absence of delivery,

actual of constructive, of the thing.

The meaning of the phrase “he shall acquire no real

right over it until the same has been delivered to him,” is

42 ‘THE LAW ON OBLIGATIONS AND Art. 1165

CONTRACTS

that the creditor does not become the owner until the specific

thing has been delivered to him. Hence, when there has

been no delivery yet, the proper court action of the creditor

is not one for recovery of possession and ownership but one

for specific performance or rescission of the obligation, (see

Art. 1165.)

EXAMPLE;

5 is obliged to give to B on July 25 a particular horse.

Before July 25, B has no right over the horse. B will acquire

a personal right against S to fulfill his obligation only from

July 25,

Ifthe horse is delivered on July 30, B acquires ownership

or real right only from that date. But if on July 20, $ sold and

delivered. the same horse to C, a third person (meaning that

he is not a party to the contract between § and B) who acted

in good faith (without knowledge of the said contract), C

acquires ownership over the horse and he shall be entitled to

it as against B.S shall be liable to B for damages. (Art. 1170.)

ART. 1165. When what is to be delivered

is a determinate thing, the creditor, in addition

to the right granted him by Article 1170, may

compel the debtor to make the delivery.

If the thing is indeterminate or generic, he

may ask that the obligation be complied with

at the expense of the debtor.

If the obligor delays, or has promised to

deliver the same thing to two or more persons

who do not have the same interest, he shall be

responsible for fortuitous event until he has

effected the delivery. (1096)

Remedies of creditor in real obligation.

(1) Ina specific real obligation (obligation to deliver a

determinate thing), the creditor may exercise the following

Veh Lbs . NATURF AND EBFECT OF 4B

OBLIGATIONS:

remedies or rights in case the debtor fails to comply with his

obligation:

(a) demand specific performance or fulfillment

(if it is still possible) of the obligation with a right to

indemnity for damages; or.

(b) demand rescission or cancellation (in certain

cases) of the obligation also with a right to recover

damages (Art. 1170.); or

{c) demand payment of damages only, where it

is the only feasible remedy.

In an obligation to deliver a determinate thing, the very

thing, itself must be delivered. (Art. 1244.) Consequently,

only the debtor can comply with the obligation. This is the

reason why the creditor is granted the right to compel the

debtor to make the delivery. (Art. 1165, par. J.)

It should be made clear, however, that the law does not

mean that the creditor can use force or violence upon the

debtor. The creditor must-bring the matter to court and the

court will be the one to order the delivery.

EXAMPLE:

S sells his piano to B for P20,000. If S refuses to comply

with his obligation to deliver the piano, B can bring an

action for fulfillment or rescission of the obligation with the

payment of damages in either case. (Art. 1191.) In case of

om, the parties must return to each other what they

have received. (Art. 1385.)

the rights to demand fulfillment and rescission with

lamapes (see Art. 1170.) are alternative, not cumulalive, ie.,

the election of one is a waiyer of the right to resort to the

other. (see Art. 1191.) B may bring an action for damages

only even if this is not expressly mentioned by Article 1165.

tome Art, 1170.)

() A yeneric real obligation (obligation to deliver a

wenerie (inp), on the other hand, can be performed by a

You might also like

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5811)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Socialscience DisciplinesDocument35 pagesSocialscience DisciplinesBianca JampilNo ratings yet

- CONTRACTSDocument8 pagesCONTRACTSBianca JampilNo ratings yet

- Financial Rehabilitation and Insolvency ActDocument15 pagesFinancial Rehabilitation and Insolvency ActBianca JampilNo ratings yet

- Glossary of Terms Ni PangetDocument8 pagesGlossary of Terms Ni PangetBianca JampilNo ratings yet

- Law On Obligations and Contracts Chapter 1Document6 pagesLaw On Obligations and Contracts Chapter 1Bianca JampilNo ratings yet

- C2 Nature and EffectDocument3 pagesC2 Nature and EffectBianca JampilNo ratings yet

- Obligation and Contracts - JampilDocument62 pagesObligation and Contracts - JampilBianca JampilNo ratings yet

- Legaspi Precious Jade C. History Narrative ReportDocument3 pagesLegaspi Precious Jade C. History Narrative ReportBianca JampilNo ratings yet

- Script For Jose RizalDocument13 pagesScript For Jose RizalBianca JampilNo ratings yet

- Jampil - Narrative A.Document1 pageJampil - Narrative A.Bianca JampilNo ratings yet

- Notebook Lesson Variant XLPurpleDocument14 pagesNotebook Lesson Variant XLPurpleBianca JampilNo ratings yet