Professional Documents

Culture Documents

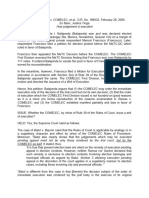

Balajonda v. COMELEC

Uploaded by

Miko TrinidadOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Balajonda v. COMELEC

Uploaded by

Miko TrinidadCopyright:

Available Formats

3B CIVIL PROCEDURE DIGESTS (1ST SEM A.Y.

2021 – 2022)

CASE NAME:

Balajonda v. COMELEC, ,

G.R. NO. G.R. No. 166032 DATE: 28 February 2005

PONENTE: Tinga, J. SUBMITTED BY: Trinidad, Mikhail B.

TOPIC: Execution, Satisfaction and Effect of Remedies – Rule 39 - How a judgment is executed

Batul also clearly shows that the judgments which may be executed pending appeal need

not be only those rendered by the trial court, but by the COMELEC as well. It stated, thus:

It is true that present election laws are silent on the remedy of execution pending appeal in

DOCTRINE: election contests. However, neither Ramas nor Santos declared that such remedy is

exclusive to election contests involving elective barangay and municipal officials as argued

by Batul. Section 2 allowing execution pending appeal in the discretion of the court applies

in a suppletory manner to election cases, including those involving city and provincial

officials.

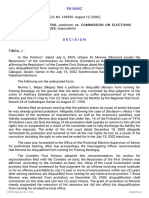

FACTS

On 16 July 2002, petitioner Elenita I. Balajonda was proclaimed as the duly elected Barangay Chairman in the

barangay elections held the previous day. Her margin of victory over private respondent Maricel Francisco 420

votes. Francisco filed an election protest, within 10 days from the date of proclamation with the MeTC of Quezon

City. In her answer, Balajonda alleged that Francisco’s petition stated no cause of action and laid stress on the fact

that although the grounds relied upon by Francisco were violations of election laws, not a single person had been

prosecuted for violation of the same.

The MeTC ordered the revision of ballots in 69 ballot boxes, and eventually, the ballots in 39 precincts were

revised. After trial, MeTC dismissed the protest with its finding that Balajonda still led Francisco by 418 votes.

Francisco appealed COMELEC. In a resolution, COMELEC First Division reversed the MeTC, finding that Francisco

won over Balajonda by 111 votes. Balajonda’s proclamation was annulled and declared, in her stead, Francisco as

the duly elected Barangay Chairman. Balajonda filed a Motion for Reconsideration while Francisco filed a Motion

for Execution in accordance with Section 2(a) of Rule 39 of the Revised Rules of Court.

Balajonda duly opposed the Motion for Execution, arguing in the main that under Sec. 2(a), Rule 39, only the

judgment or final order of a trial court may be the subject of discretionary execution pending appeal. However the

COMELEC First Division granted the motion and directed the issuance of a Writ of Execution, ordering Balajonda

to cease and desist from discharging her functions as Barangay Chairman and relinquish said office to Francisco.

Balajonda in essence submits the following grounds, thus: (1) that the COMELEC may order the immediate

execution only of the decision of the trial court but not its own decision; (2) that the order of execution which the

COMELEC First Division issued is not founded on good reasons as it is a mere pro forma reproduction of the

reasons enumerated in Ramas v. COMELEC; and (3) the COMELEC exhibited manifest partiality and bias in favor

of Francisco when it transgressed its own rule. Balajonda invoked only the first ground in her opposition to

the Motion For Execution, but definitely not the second and third. In any event, all the grounds are bereft of merit.

l^vvphi1.net

ISSUES

Whether or not the Commission on Elections has power to order the immediate execution of its judgment or final

order involving a disputed barangay chairmanship

RULING OF THE COURT

Yes. Despite the silence of the COMELEC Rules of Procedure as to the procedure of the issuance of a writ of

execution pending appeal, there is no reason to dispute the COMELEC’s authority to do so, considering that the

suppletory application of the Rules of Court is expressly authorized by Section 1, Rule 41 of the COMELEC Rules

3B CIVIL PROCEDURE DIGESTS (1ST SEM A.Y. 2021 – 2022)

of Procedure which provides that absent any applicable provisions therein the pertinent provisions of the Rules of

Court shall be applicable by analogy or in a suppletory character and effect. The public policy underlying the

suppletory application of Sec. 2(a), Rule 39 is to obviate a hollow victory for the duly elected candidate as

determined by either the courts or the COMELEC. Towards that end, we have consistently employed liberal

construction of procedural rules in election cases to the end that the will of the people in the choice of public officers

may not be defeated by mere technical objections. Balajonda’s argument is anchored on a simplistic, literalist

reading of Sec. 2(a), Rule 39 that barely makes sense, especially in the light of the COMELEC’s specialized and

expansive role in relation to election cases.

NOTES

You might also like

- Supreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionFrom EverandSupreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionNo ratings yet

- Petition for Certiorari Denied Without Opinion: Patent Case 98-1151From EverandPetition for Certiorari Denied Without Opinion: Patent Case 98-1151No ratings yet

- Elenita I. Balajonda v. COMELEC, Et Al., G.R. No. 166032, February 28, 2005Document2 pagesElenita I. Balajonda v. COMELEC, Et Al., G.R. No. 166032, February 28, 2005Emmanuel SilangNo ratings yet

- Balajonda Vs COMELEC, GR No. 166032, Feb. 28, 2005Document7 pagesBalajonda Vs COMELEC, GR No. 166032, Feb. 28, 2005Iya LumbangNo ratings yet

- Article IX Case Digest PDFDocument6 pagesArticle IX Case Digest PDFKirt CatindigNo ratings yet

- Article IX Case Digest - C. Commission On ElectionDocument6 pagesArticle IX Case Digest - C. Commission On ElectionKirt CatindigNo ratings yet

- Article IX Case Digest - C. Commission On Election PDFDocument6 pagesArticle IX Case Digest - C. Commission On Election PDFKirt CatindigNo ratings yet

- Francisco v. CA G.R. No. 108747 April 6, 1995Document10 pagesFrancisco v. CA G.R. No. 108747 April 6, 1995Santos, CarlNo ratings yet

- Munoz vs. Comelec: Results of The Election. (Emphasis Supplied)Document43 pagesMunoz vs. Comelec: Results of The Election. (Emphasis Supplied)Sittie Rainnie BaudNo ratings yet

- Cases Reported: Supreme Court Reports AnnotatedDocument23 pagesCases Reported: Supreme Court Reports Annotatedobladi obladaNo ratings yet

- Marquez Vs COMELECDocument3 pagesMarquez Vs COMELECKirsten Denise B. Habawel-VegaNo ratings yet

- En Banc G.R. No. 168550 August 10, 2006 URBANO M. MORENO, Petitioner, vs. Commission On Elections and Norma L. Mejes, Chico-Nazario, Respondents. DecisionDocument90 pagesEn Banc G.R. No. 168550 August 10, 2006 URBANO M. MORENO, Petitioner, vs. Commission On Elections and Norma L. Mejes, Chico-Nazario, Respondents. DecisionNicco AcaylarNo ratings yet

- Urbano Moreno Vs COMELECDocument7 pagesUrbano Moreno Vs COMELECatn_reandelarNo ratings yet

- Moreno V ComelecDocument6 pagesMoreno V ComelecChriselle Marie DabaoNo ratings yet

- Crim Rev - 7 (Finals)Document39 pagesCrim Rev - 7 (Finals)Ross Camille SalazarNo ratings yet

- Alunan Vs MirasolDocument6 pagesAlunan Vs MirasolLara Elize ItaoNo ratings yet

- Election Laws Next Cases Week Ending July 19Document4 pagesElection Laws Next Cases Week Ending July 19Amanda ButtkissNo ratings yet

- Comelec Cases:: Brillantes VDocument7 pagesComelec Cases:: Brillantes VChristina AureNo ratings yet

- Flores v. COMELECDocument2 pagesFlores v. COMELECLance LagmanNo ratings yet

- Digests Rule 39Document11 pagesDigests Rule 39Judy BubanNo ratings yet

- Salva v. Makalintal - Sahali v. COMELECDocument6 pagesSalva v. Makalintal - Sahali v. COMELECMariaAyraCelinaBatacanNo ratings yet

- Marquez v. Comelec DigestDocument2 pagesMarquez v. Comelec DigestkathrynmaydevezaNo ratings yet

- Case Digests Powers 1Document4 pagesCase Digests Powers 1Your Public ProfileNo ratings yet

- CD - 29 Antonio Vs ComelecDocument2 pagesCD - 29 Antonio Vs ComelecAlyssa Alee Angeles Jacinto100% (1)

- Grego Vs COMELECDocument2 pagesGrego Vs COMELECxsar_xNo ratings yet

- Election Law de Leon PDFDocument15 pagesElection Law de Leon PDFLemuel Angelo M. Eleccion0% (1)

- ElecLAw - Moreno vs. Comelec and Mejes, G.R. No. 168550 August 10, 2006Document2 pagesElecLAw - Moreno vs. Comelec and Mejes, G.R. No. 168550 August 10, 2006Lu CasNo ratings yet

- Romeo Jalosjos v. ComelecDocument2 pagesRomeo Jalosjos v. ComelecHudson CeeNo ratings yet

- Grego V COMELEC DigestDocument2 pagesGrego V COMELEC DigestKaren HaleyNo ratings yet

- 2.2.C. People v. Judge IntingDocument1 page2.2.C. People v. Judge IntingAronJamesNo ratings yet

- Antonio vs. COMELECDocument1 pageAntonio vs. COMELECEdz Votefornoymar Del Rosario100% (1)

- 3.castillo V ComelecDocument5 pages3.castillo V ComelecLorenzo CzarNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 122013 March 26, 1997 Ramirez Vs ComelecDocument4 pagesG.R. No. 122013 March 26, 1997 Ramirez Vs ComelecRey Almon Tolentino AlibuyogNo ratings yet

- Magno Vs ComelecDocument3 pagesMagno Vs ComelecEddie MagalingNo ratings yet

- Antonio V ComelecDocument10 pagesAntonio V ComelecVon Claude Galinato AlingcayonNo ratings yet

- Admin 01 Ra 8048Document24 pagesAdmin 01 Ra 8048Mitos EvangelistaNo ratings yet

- 27 Francisco V COMELEC - Prior COurt JudgmentDocument18 pages27 Francisco V COMELEC - Prior COurt JudgmentNathaniel CaliliwNo ratings yet

- 6 Buac and Bautista vs. ComelecDocument4 pages6 Buac and Bautista vs. Comelec유니스No ratings yet

- Vs. Hon. Roberto L. Makalintal, Et AlDocument4 pagesVs. Hon. Roberto L. Makalintal, Et AlMariel CabubunganNo ratings yet

- Search Result: ReferenceDocument16 pagesSearch Result: ReferenceLazy IzzyNo ratings yet

- MENDOZA v. COMELEC - Case DigestDocument2 pagesMENDOZA v. COMELEC - Case DigestJane BanaagNo ratings yet

- I. Gomez-Castillo V. Comelec: Supreme CourtDocument73 pagesI. Gomez-Castillo V. Comelec: Supreme CourtAya BeltranNo ratings yet

- Violago V COMELEC DigestDocument5 pagesViolago V COMELEC DigestLucioJr AvergonzadoNo ratings yet

- Consti Cases ComelecDocument28 pagesConsti Cases ComelecWTI billingNo ratings yet

- Violago SR Vs COmelecDocument11 pagesViolago SR Vs COmelecShivaNo ratings yet

- Public Corp CasesDocument119 pagesPublic Corp CasesNoevir Maganto MeriscoNo ratings yet

- Ramirez v. ComelecDocument5 pagesRamirez v. ComelecRashid Vedra PandiNo ratings yet

- Edding V ComelecDocument6 pagesEdding V ComelecVienna Mantiza - PortillanoNo ratings yet

- 121860-2006-Moreno v. Commission On ElectionsDocument7 pages121860-2006-Moreno v. Commission On ElectionsChezca MargretNo ratings yet

- Cases For Probation and RA 8294Document28 pagesCases For Probation and RA 8294Grasya AlbanoNo ratings yet

- Statcon Dec5Document15 pagesStatcon Dec5Jonah BinaraoNo ratings yet

- Consti Nov. 15Document15 pagesConsti Nov. 15Ynna GesiteNo ratings yet

- Election Digested CasesDocument24 pagesElection Digested CasesDarlette Villanueva Ladrido100% (1)

- Villamor v. ComelecDocument2 pagesVillamor v. Comelecrgtan3No ratings yet

- A. Compilation - Election - SuffrageDocument18 pagesA. Compilation - Election - SuffragecmontefalconNo ratings yet

- Moreno V ComelecDocument9 pagesMoreno V ComelecraykarloBNo ratings yet

- Petitioner Respondents: Urbano M. Moreno, - Commission On Elections and Norma L. MejesDocument7 pagesPetitioner Respondents: Urbano M. Moreno, - Commission On Elections and Norma L. MejesJanelle Leano MarianoNo ratings yet

- Francisco V Commission On ElectionsDocument19 pagesFrancisco V Commission On ElectionsRizza MoradaNo ratings yet

- Election Law Digests Ateneo Law School 3DDocument29 pagesElection Law Digests Ateneo Law School 3DEmosNo ratings yet

- Admin Case Digest 1Document15 pagesAdmin Case Digest 1Isobel Dayandra Lucero PelinoNo ratings yet

- Pacis v. Commission On ElectionsDocument2 pagesPacis v. Commission On ElectionsMiko TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Spouses Laus v. Optimum Security ServicesDocument2 pagesSpouses Laus v. Optimum Security ServicesMiko TrinidadNo ratings yet

- BA Finance Corp. v. Court of AppealDocument2 pagesBA Finance Corp. v. Court of AppealMiko TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Allied Banking Corp. v. Court of AppealsDocument2 pagesAllied Banking Corp. v. Court of AppealsMiko TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Islamic Da'wah Council of The Philippines v. Court of AppealsDocument3 pagesIslamic Da'wah Council of The Philippines v. Court of AppealsMiko TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Valencia v. Court of AppealsDocument5 pagesValencia v. Court of AppealsMiko TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Jud AffDocument5 pagesJud AffMiko TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Poe V COMELECDocument7 pagesPoe V COMELECMiko TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Malabanan Vs RamentoDocument2 pagesMalabanan Vs RamentoMiko TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Reyes Vs AlejandroDocument1 pageReyes Vs AlejandroMiko TrinidadNo ratings yet

- 02-Iba2019 Cover PDFDocument1 page02-Iba2019 Cover PDFMiko TrinidadNo ratings yet

- 11 - Augustin v. EduDocument2 pages11 - Augustin v. EduMiko TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Freedom of Assembly and PetitionDocument5 pagesFreedom of Assembly and PetitionMiko TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Case Title G.R. NO. G.R. No. 190520: AL DELA CRUZ, Petitioner Capt. Renato Octa Viano and Wilma Octa VianoDocument2 pagesCase Title G.R. NO. G.R. No. 190520: AL DELA CRUZ, Petitioner Capt. Renato Octa Viano and Wilma Octa VianoMiko TrinidadNo ratings yet

- R Transport Corporation v. YuDocument1 pageR Transport Corporation v. YuMiko TrinidadNo ratings yet

- PF Case ListDocument1 pagePF Case ListMiko TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Lampas-Peralta vs. RamonDocument2 pagesLampas-Peralta vs. RamonMiko TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Crim Running DigestDocument16 pagesCrim Running DigestMiko TrinidadNo ratings yet

- PFR CasesDocument21 pagesPFR CasesKaren Sheila B. Mangusan - DegayNo ratings yet

- 8th Case BernabeDocument2 pages8th Case BernabeJoshua Paril100% (1)

- Transportation Law Landmark Cases Part 1Document27 pagesTransportation Law Landmark Cases Part 1hanabi_13No ratings yet

- SRCR012538 - Charge of Theft 4th Degree Against Early Woman Dismissed PDFDocument39 pagesSRCR012538 - Charge of Theft 4th Degree Against Early Woman Dismissed PDFthesacnewsNo ratings yet

- Tua v. Mangrobang Case DigestDocument2 pagesTua v. Mangrobang Case DigestShannin MaeNo ratings yet

- Webb Report and RecDocument54 pagesWebb Report and RecjhbryanNo ratings yet

- MOSES Memorandum Opposing TRATON Motion For Attorneys Fees FINALDocument31 pagesMOSES Memorandum Opposing TRATON Motion For Attorneys Fees FINALDocument Repository100% (2)

- Oxford Motion To Dismiss Ryan MooreDocument12 pagesOxford Motion To Dismiss Ryan MooreMarie ForrestNo ratings yet

- Motion For ReconsiderationDocument5 pagesMotion For ReconsiderationAhtashamNo ratings yet

- Human Rights Chapter VII CasesDocument48 pagesHuman Rights Chapter VII CasesVic RabayaNo ratings yet

- 24 Republic Vs JimenezDocument15 pages24 Republic Vs JimenezzelayneNo ratings yet

- VOL. 214, SEPTEMBER 25, 1992 273: Lim vs. Court of AppealsDocument15 pagesVOL. 214, SEPTEMBER 25, 1992 273: Lim vs. Court of AppealsCharles RiveraNo ratings yet

- Aguiar v. Webb Et Al - Document No. 112Document2 pagesAguiar v. Webb Et Al - Document No. 112Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Crim Pro Case DigestDocument32 pagesCrim Pro Case DigestKei ShaNo ratings yet

- Hossu Gomberg MotionDocument27 pagesHossu Gomberg MotionHudson Valley Reporter- PutnamNo ratings yet

- Francisco Cabral v. William Sullivan, Francisco Cabral v. William Sullivan, 961 F.2d 998, 1st Cir. (1992)Document8 pagesFrancisco Cabral v. William Sullivan, Francisco Cabral v. William Sullivan, 961 F.2d 998, 1st Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Muhammad v. Calbone, 10th Cir. (2005)Document7 pagesMuhammad v. Calbone, 10th Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Tagastason Vs PeopleDocument8 pagesTagastason Vs PeopleFacio BoniNo ratings yet

- Art 3 Sec 2Document112 pagesArt 3 Sec 2Matthew WittNo ratings yet

- Tyrone Lamont Allen Motion To SuppressDocument11 pagesTyrone Lamont Allen Motion To SuppressNational Content DeskNo ratings yet

- Motion To Dismiss Credit Card LawsuitDocument7 pagesMotion To Dismiss Credit Card LawsuitRf Goodie100% (7)

- Department of Labor: 02 008Document9 pagesDepartment of Labor: 02 008USA_DepartmentOfLaborNo ratings yet

- Canada Tobacco-Related LitigationDocument29 pagesCanada Tobacco-Related LitigationIndonesia TobaccoNo ratings yet

- AAG Trucking Vs YuagDocument4 pagesAAG Trucking Vs YuagBenj BulawanNo ratings yet

- Rule 110 Section 14 CasesDocument75 pagesRule 110 Section 14 CasesMicah Clark-MalinaoNo ratings yet

- New Georgia Project v. Attorney General Opening BriefDocument81 pagesNew Georgia Project v. Attorney General Opening BriefBrent LieagleNo ratings yet

- Motion For Emergency Stay and For Review of A Release OrderDocument29 pagesMotion For Emergency Stay and For Review of A Release OrderNews10NBCNo ratings yet

- Writingexercisesforlawstudents 001Document13 pagesWritingexercisesforlawstudents 001NataliaNo ratings yet

- Taxation LawDocument40 pagesTaxation Lawnelzahumiwat0No ratings yet

- FIRST BANK OF MARIETTA, Plaintiff-Appellant/Cross-Appellee, v. Hartford Underwriters Insurance Company, Defendant-Appellee/Cross-AppellantDocument47 pagesFIRST BANK OF MARIETTA, Plaintiff-Appellant/Cross-Appellee, v. Hartford Underwriters Insurance Company, Defendant-Appellee/Cross-AppellantScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet