Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sociology of Education

Uploaded by

diannpOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sociology of Education

Uploaded by

diannpCopyright:

Available Formats

Sociology of Education http://soe.sagepub.

com/

Leveling the Home Advantage: Assessing the Effectiveness of Parental Involvement in Elementary

School

Thurston Domina

Sociology of Education 2005 78: 233

DOI: 10.1177/003804070507800303

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://soe.sagepub.com/content/78/3/233

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

American Sociological Association

Additional services and information for Sociology of Education can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://soe.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://soe.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://soe.sagepub.com/content/78/3/233.refs.html

>> Version of Record - Jul 1, 2005

What is This?

Downloaded from soe.sagepub.com at CARLETON UNIV on November 28, 2014

Leveling the Home Advantage:

Assessing the Effectiveness of

Parental Involvement in Elementary

School

Thurston Domina

City University of New York

In the past two decades, a great deal of energy has been dedicated to improving children’s

education by increasing parents’ involvement in school. However, the evidence on the effec-

tiveness of parental involvement is uneven. Whereas policy makers and theorists have assumed

that parental involvement has wide-ranging positive consequences, many studies have shown

that it is negatively associated with some children’s outcomes. This article uses data from the

children of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 to estimate time-lagged growth

models of the effect of several types of parental involvement on scores on elementary school

achievement tests and the Behavioral Problems Index. The findings suggest that parental

involvement does not independently improve children’s learning, but some involvement activ-

ities do prevent behavioral problems. Interaction analyses suggest that the involvement of par-

ents with low socioeconomic status may be more effective than that of parents with high

socioeconomic status.

I

n the past two decades, a great deal of been even more pronounced. A 1995–96 sur-

research and policy-making activity has vey by the National Center for Education

been dedicated to increasing the involve- Statistics showed that nearly all public ele-

ment of parents in schools. Parental-involve- mentary and middle schools in the United

ment initiatives have been a mainstay of fed- States sponsored activities that were

eral educational policy since the Reagan designed to foster parental involvement.

administration’s 1986 Goals 2000: Educate According to the survey, 97 percent of

America Act. In 1996, the Clinton administra- schools invited parents to attend an open

tion reauthorized the Elementary and house or back-to-school night, 92 percent

Secondary Education Act, adding a new pro- scheduled parent-teacher conferences, 96

vision that required the nation’s poorest percent hosted arts events, 85 percent spon-

schools to spend at least 1 percent of their sored athletic events, and 84 percent had sci-

Title I supplementary federal funds to develop ence fairs (Carey et al. 1998). Throughout the

educational “compacts” between families United States, parental-involvement initia-

and schools. Likewise, increasing parental tives have been central to state- and dis-

involvement in schools is one of the six cen- trictwide school reform efforts, most notably

tral goals of the Bush administration’s 2002 in Baltimore, Chicago, and Philadelphia

No Child Left Behind Act. (Epstein 2001; Fine 1993; Wallace and

At the state and local levels, interest and Walberg 1991). In 2003–04, New York City

activity surrounding parental involvement has schools chancellor Joel Klein appropriated

Sociology of Education 2005, Vol. 78 (July): 233–249 233

Downloaded from soe.sagepub.com at CARLETON UNIV on November 28, 2014

234 Domina

$43 million to hire parent coordinators to children’s cognitive achievement and their

arrange school events and contact parents in behavioral problems. The NLSY79’s longitudi-

each of the system’s 1,200 schools (Gootman nal design makes it possible to place parental

2003). activities in the context of children’s earlier

The spread of parental-involvement poli- achievement and behavior. Using a repeated-

cies reflects the application of key insights measures approach, I estimated the effects of

from the sociology of education to the day- parental involvement on achievement and

to-day operation of American schools. As behavior, net of earlier achievement and

Epstein (1986, 1987a, 1987b) argued, behavior. Finally, I used interaction terms to

parental-involvement efforts acknowledge determine whether the effects of parental-

the crucial role that families and communities involvement activities vary by parents’ socioe-

play in children’s education. They attempt to conomic status (SES).

moderate upper- and middle-class students’

home advantage by bringing all families,

regardless of social class or race, into the daily PREVIOUS RESEARCH

life of the school. Parental-involvement poli-

cies seek to redistribute cultural and social Given the popularity of parental-involvement

capital, boosting the resources that are avail- initiatives as a tool for school reform, it is sur-

able to disadvantaged children. They are prising to note that research on the link

thought to foster social closure by creating between involvement and school success has

opportunities for parents, teachers, and been inconclusive. A few national studies

administrators to network and share informa- have associated high levels of parental

tion with one another. involvement with improved educational out-

But does parental involvement deserve the comes for children (Fehrmann, Keith, and

faith that the public has invested in it? Reimers 1987; Stevenson and Baker 1987;

Researchers have generally agreed that Useem 1992), but others have reported that

parental-involvement activities are associated parental involvement in education is nega-

with stronger educational outcomes, but it is tively related to children’s educational out-

not clear that these activities cause educa- comes (Fan 2001; Milne et al. 1986). Even

tional success (A. Baker and Soden 1998; within studies, the results have often been

Downey 2002). Indeed, evidence regarding mixed, with the observed effects of parental

the effectiveness of parental involvement has involvement depending on which aspects of

been mixed and largely discouraging. Many involvement and which educational out-

studies have suggested that the parental- comes have been considered (Crosnoe

involvement activities that are most frequent- 2001b; Ho and Willms 1996; Keith 1991;

ly targeted by schools have little or no direct Miedel and Reynolds 1999; Muller 1993;

influence on children’s educational outcomes; Singh et al. 1995).

others have indicated that the effectiveness of Indeed, a review of multivariate studies of

parental involvement may be conditional on the effectiveness of parental involvement yield-

parents’ race and class. However, these find- ed no single parental-involvement activity that

ings may be misleading. Past researchers on was consistently linked to favorable children’s

parental involvement have focused on cogni- outcomes. For example, whereas Catsambis

tive and academic outcomes, neglecting the (1998), Muller (1993) and Ho and Willms

effect of involvement on children’s behavior. (1996) reported positive effects of parents’ at-

Furthermore, most have studied middle home educational supervision, Desimone

school and high school students, rather than (2001) reported negative effects, and Fan

elementary school students. (2001) and McNeal (1999) reported nonsignif-

I used data on the elementary school-aged icant findings. Even within studies, the estimat-

children of the National Longitudinal Survey ed effects of particular parental-involvement

of Youth 1979 cohort (NLSY79) to investigate activities have varied according to the outcome

the relationship between six forms of parental measured. For example, Desimone (2001) and

involvement and two distinct outcomes— McNeal (1999) found that attendance at

Downloaded from soe.sagepub.com at CARLETON UNIV on November 28, 2014

Leveling the Home Advantage 235

Parent-Teacher Association (PTA) meetings is middle- and high school students. This focus

associated with positive values on some chil- may have caused researchers to underesti-

dren’s outcomes and negative values on others. mate the effects of parental involvement.

The one area in which recent studies have Parents’ involvement in school tends to

seemed to agree is one in which involvement decline as children age (Catsambis and

has a counterintuitive negative effect on chil- Garland 1997; Crosnoe 2001a), as does its

dren’s educational outcomes; Catsambis effectiveness (Catsambis and Suazo-Garcia

(1998), Desimone (2001), Fan (2001), Muller 2000; Muller 1998; Singh et al. 1995). The

(1993), and Ho and Willms (1996) all reported only relatively recent study that analyzed the

a significant, negative association between par- involvement of parents of elementary school

ents’ educational contacts with schools and students using quantitative methods (Miedel

children’s educational outcomes. and Reynolds 1999) found that parental

Studies that have used other methodolo- involvement improves the reading scores of

gies have yielded similarly ambiguous find- kindergarteners but has no effect on the read-

ings. Among qualitative studies, Comer ing scores of high school students.

(1980), Comer and Haynes (1991), Epstein Furthermore, most parental-involvement pol-

(2001), and Lareau (1989) reported positive icy-making activity has focused on increasing

effects of parental involvement. Fine (1993) the involvement of children in elementary

and Reay (1998), however, argued that school (Chen and Chandler 2001). It is possi-

observed associations between parental par- ble that these initiatives could be effective,

ticipation and children’s educational perfor- even if the effects of parental involvement on

mance are really artifacts of the class and high school-aged children are negligible. This

racial advantages that involved parents bring article addresses this oversight in the litera-

to the table. The evidence from evaluations of

ture by estimating the implications of

parental-involvement programs has been no

parental-involvement activities for a sample of

more encouraging. Mattingly et al. (2002)

elementary school students.

reviewed the evaluations of 41 school- and

district-level parental-involvement programs

and concluded that there is little empirical Conceptualizing Parental

evidence to support the claim that schools’ Involvement and Its Effects

efforts to improve parental involvement ulti-

Influenced by Epstein’s (1992) typology of

mately improve students’ outcomes. Only

parental involvement—a typology that

half the parental-involvement studies that

includes basic parental roles like keeping chil-

Mattingly et al. considered to be adequately

dren safe, as well as higher-level involvement

designed found positive effects of parental-

involvement programs. activities, such as collaborating with commu-

nity organizations—researchers on parental

involvement have considered a variety of

activities as examples of parental involve-

EXPLANATIONS FOR THE ment. By contrast, analyses of the implica-

UNEVEN EFFECTS tions of involvement have been narrowly

focused on children’s cognitive and academic

Given the resources that have been dedicated achievement. As McNeal (1999) pointed out,

to parental involvement, these findings are dis- this tight analytic focus may come at a cost.

couraging. However, previous research on McNeal argued that the conceptual ties

parental involvement may have underestimat- between most forms of parental involvement

ed its effect by neglecting the following four and children’s learning are weak compared to

considerations. the ties between parental involvement and

children’s behavior.

Differential Effects by Students’ Ages Involvement may be expected to influence

children’s outcomes via three mechanisms:

Nearly all past research on the effectiveness of

parental involvement has been conducted on • Parental involvement socializes. When, for exam-

Downloaded from soe.sagepub.com at CARLETON UNIV on November 28, 2014

236 Domina

ple, parents supervise their children’s home- Separating the Causes and Effects

work, they convey the importance of school-

ing.

of Involvement

• Second, parental involvement generates social

Researchers have often explained negative

control. Parents who attend PTA meetings and and nonsignificant associations between par-

volunteer in school develop relationships with ents’ involvement in school and children’s

their children’s teachers and the parents of outcomes by arguing that the direction of

their children’s classmates. These relationships causal effects between involvement and edu-

make it easier for parents to monitor children’s cational outcomes is ambiguous. According

behavior and teachers’ practices. to this argument, when children are experi-

encing difficulties in school, their parents are

• Parental involvement gives parents access to

insider information. When children have prob- more likely to schedule meetings with teach-

lems at school, involved parents learn about ers and to become involved, but when chil-

these problems earlier and know more about dren are succeeding in school, their parents

available solutions. tend to relax their involvement in school

(Crosnoe 2001a; McNeal 1999; Muller 1998;

McNeal argued that since the mechanisms Sanders 1998).This explanation suggests that

vary, different types of parental involvement cross-sectional estimates of the effect of

will have different effects on children’s cogni- involvement are biased, since they neglect

tive and behavioral outcomes. Socialization the cross-cutting influence of prior perfor-

primarily affects children’s behavior and mance.1

engagement. Similarly, the social-control A handful of studies have adopted a longi-

aspects of parental involvement tend to curb tudinal survey design to address causal direc-

children’s problem behaviors, but do relative- tion. Singh et al.’s (1995) study tested the

ly little to influence children’s learning. Only effect of parental involvement on students’

the insider-information element of parental eighth-grade academic achievement with a

involvement, McNeal contended, directly control for prior grades. Muller (1998) and

influences both children’s cognitive and Fan (2001) used a more-rigorous, repeated-

behavioral outcomes. measures approach. Their analyses took

Researchers who have focused on the cog- advantage of the repeated measures available

nitive effects of parental involvement may in the National Education Longitudinal Study

have overlooked more dramatic implications (NELS) of 1988 to model the effect of

of involvement for children’s behavior. This parental involvement on high school stu-

article models the effect of six parental- dents’ achievement, net of prior achievement

involvement activities on children’s behav- scores. These studies controlled for potential

ioral and cognitive development. Following reverse-causality bias, but their estimates of

McNeal (1999), I argue that the six parental- the effect of parental involvement were no

involvement activities influence children’s less ambiguous than were those of earlier

outcomes in different ways: Two of the studies. Muller found that children who dis-

parental-involvement variables that are cuss school with their parents experience rel-

included in my analyses measure the extent atively rapid growth in math achievement,

to which parents are engaged in students’ but otherwise, both Muller and Fan found

homework, an activity that primarily affects that most parental-involvement activities

students’ outcomes via socialization. Three of have, at best, no effect on the cognitive

the involvement measures—attending PTA development of high school students.

meetings and volunteering inside and outside This article also adopts a repeated-mea-

the classroom—tap involvement in activities sures approach, using NLSY data for elemen-

that allow parents to exercise social control tary school students. The approach tests the

over their children. In addition, my analysis hypothesis that parental involvement is both

includes a measure of attendance at parent- the cause and the effect of children’s elemen-

teacher conferences, an activity that exposes tary school performance by examining the

parents to insider information. effects of parental involvement net of chil-

Downloaded from soe.sagepub.com at CARLETON UNIV on November 28, 2014

Leveling the Home Advantage 237

dren’s prior cognitive achievement and children’s cognitive and behavioral develop-

behavior. ment. The NLSY79 began in 1979, collecting

data on the family background, labor market

Heterogeneity of Causal Effects experience, and educational history of a sam-

ple of 12,686 American children and young

Recent theoretical and empirical work has adults aged 14–22. Annual follow-up surveys

pointed to the possibility that the efficacy of tracked the school-to-work transition of this

particular parental-involvement activities original cohort, and in 1986, the NLSY79 ini-

varies according to parents’ race, ethnicity, tiated a mother-child sample, focusing on the

and class background (Desimone 2001; children of the NSLY79 respondents. In addi-

Lareau and Horvat 1999; McNeal 1999). tion to surveying mothers and children about

Taken as a whole, this line of inquiry suggests their families, friends, and schooling, the

that the involvement efforts of middle-class NLSY79 has administered a battery of cogni-

and white parents may meet with greater tive and socioemotional assessments to the

educational rewards than may the involve- children biannually (Baker et al. 1993; U.S.

ment efforts of poor and minority parents. Department of Labor 2001).

Potential heterogeneity in the causal Researchers have relied heavily on NLSY79

effects of parental involvement has profound data to analyze the influence of parents’

implications for the effectiveness of parental socioeconomic characteristics on children’s

involvement as a school reform strategy. If educational development (see, e.g., Duncan

Desimone (2001), Lareau and Horvat (1999), and Brooks-Gunn 1997; Mayer 1997; Parcel

and McNeal (1999) were correct that the and Menaghan 1994). However, I know of

positive effects of parental involvement are only one study that used NLSY79 mother-

the strongest for the most-advantaged fami- child data to assess the influence of parental

lies, a general increase in parental-involve- involvement, and that study was limited to a

ment activities may actually widen gaps in small subsample of respondent children who

educational achievement, rather than amelio- were enrolled in the Head Start program

rate them. (Cohen 2002). The NLSY79 is uniquely suited

To address these issues, I used time-lagged to research on parental involvement, since it

models to investigate the possibility that the provides rich data on parental involvement

effects of parental involvement vary by par- and multiple children’s educational and

ents’ socioeconomic background by testing behavioral outcome measures. In addition, it

for interactions between the effects of provides repeated observations of children

involvement activities and parents’ SES.2 If while they are still in elementary school,

these analyses show greater returns to the which distinguishes it from the NELS, the

involvement of high-SES parents, the progno- data set that has most often been used in

sis for parental-involvement programs as a recent research on parental involvement.

tool for generating educational equity is grim. I studied 1,445 children of NLSY79 respon-

If, on the other hand, they show that the dents. These children were enrolled in ele-

involvement of disadvantaged parents has a mentary school in 1996 and completed the

stronger effect than the involvement of rela- NLSY79’s Peabody Individual Achievement

tively affluent parents, even modest effects of Test (PIAT) and the Behavior Problems Index

parental involvement could have major con- (BPI) in 1996 and 2000.4 All the children in

sequences for improving educational equity. this sample were in the fourth or lower grades

in 1996, and the median student was

enrolled in the second grade. I followed these

DATA AND METHODS children through three survey rounds, look-

ing at the effect of parents’ school-involve-

I used longitudinal data from the mother- ment activities in 1996 on the children’s 2000

child sample of the NLSY793 to sort out the PIAT and BPI scores. Since the NLSY purpose-

relationship between several parental school- ly oversampled the economically disadvan-

involvement activities and elementary school taged, African Americans, and Hispanics in

Downloaded from soe.sagepub.com at CARLETON UNIV on November 28, 2014

238 Domina

the construction of the initial 1979 cohort et al. 2001; King et al. 2001).6 Table 1 pre-

and since response rates in the screening sents weighted descriptive statistics for each

process and in subsequent interviews varied variable that was used in the analyses.

by race and other characteristics, I used the

NLSY’s 2000 child weights to correct for Dependent Variables

potential biases.5 Although rates of nonre-

sponse were low, listwise deletion would dis- Using ordinary least-squares (OLS) regression

card nearly one third of the cases in my sam- models, I assessed the effect of the six

ple. As King et al. (2001) demonstrated, the parental school-involvement activities on two

result would be the loss of valuable informa- outcomes: the PIAT and the BPI. The PIAT

tion and could cause severe selection bias. To measures children’s academic achievement

avoid these problems, I filled missing data (Dunn and Markwardt 1970). This composite

using Amelia multiple imputation, a tech- score is the mean of the child’s age-standard-

nique that has been demonstrated to pro- ized percentile scores on subtests in mathe-

duce more reliable data than other tech- matics, reading recognition, and reading

niques for dealing with missing data (Honaker comprehension, each of which consists of 84

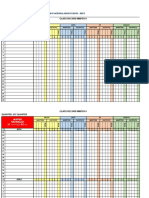

Table 1. Variables Used in the Analyses: Descriptive Statistics of NLSY79 Elementary School

Children

Variables Range Mean SD

Dependent Variables

2000 Composite PIAT percentile score 0–100 57.88 24.84

2000 BPI percentile score 0–100 56.83 28.03

Parental Involvement Variables

Parents attended PTA meeting, 1996 0–1 .550 .498

Parents attended one-on-one meeting with

teacher or school official, 1996 0–1 .937 .242

Parents volunteered in classroom, 1996 0–1 .608 .488

Parents volunteered outside the classroom, 1996 0–1 .641 .480

How often parents helped with homework, 1996 0–5 3.11 1.72

How often parents checked homework, 1996 0–5 3.88 1.65

Background Control Variables

Black 0–1 .140 .347

Hispanic 0–1 .071 .258

Other 0–1 .073 .260

Male 0–1 .518 .500

Dummy, child attended public school, 1996 0–1 .855 .353

Dummy, child lived with mother and her

spouse/partner, 1996 0–1 .791 .407

Child’s grade in 1996 0–4 1.82 1.38

Family SES, 1996 -2.26–2.46 0 .69

Prior Performance Control Variables

1996 Composite PIAT percentile score 0–100 51.66 18.11

1996 BPI percentile score 0–100 57.79 27.43

Child repeated a grade before 1996 0–1 .052 .222

Downloaded from soe.sagepub.com at CARLETON UNIV on November 28, 2014

Leveling the Home Advantage 239

multiple-choice items.7 These three subtests parental-involvement activities on children’s

have high reliability and correlate closely with outcomes: how often the parents helped the

a variety of other cognitive measures.8 children with homework and how often the

The BPI measures the frequency, range, parents checked the children’s homework.

and type of childhood behavioral problems. These measures of home involvement are

This measure is derived from mothers’ scale variables, ranging from 0 (for children

responses to 28 questions about their chil- whose parents never checked or helped with

dren’s behavior in the three months before homework) to 5 (for children whose parents

they were surveyed. Among the behaviors checked or helped with homework every

included in the BPI are cheating and lying, day). Although these two variables correlate

argumentativeness, difficulty concentrating, with one another at .52, they do not correlate

bullying, disobedience at home and at closely with the school-involvement variables,

school, trouble getting along with other chil- and post-hoc multicollinearity tests suggested

dren, trouble getting along with teachers, that they do not create multicollinearity issues

and impulsiveness.9 The BPI is a negative in the regression models.11

measure; a high score on the BPI indicates It should be noted that these measures of

many behavioral problems. parental involvement are less precise than

one may like.12 The four measures of parental

Measures of Parental Involvement participation in school activities are blunt; as

dichotomous measures, they blur the distinc-

I used six NLSY variables to measure aspects tion between parents who regularly partici-

of parental involvement. Four of these vari- pate in school activities and those who do so

ables measure parental participation in infrequently. Likewise, by focusing exclusively

school-based parental-involvement activities, on help with homework, the measures of at-

and two measure at-home parental involve- home parental involvement miss more-

ment in the educational process. The NLSY nuanced forms of parental involvement, such

includes several more-general questions as discussing school lessons and engaging in

about parent-child relations, but these six informal academic coaching. These data limi-

questions most directly tap the involvement tations likely have a conservative effect on the

of parents in children’s education. reported findings; since the data imperfectly

The four school-involvement measures are capture parental involvement, estimates of

attendance at parent-teacher conferences, the effectiveness of involvement could be

participation in the PTA, volunteering in the understated.

classroom, and volunteering outside the

classroom (such as supervising lunch and Control Variables

chaperoning field trips). These items are all

dichotomous, and each is based on inter- Socioeconomic Background I took several

views with the mothers. Mothers who said characteristics of children’s social, economic,

that they or their husbands or partners par- and family backgrounds into account to con-

ticipated in the school activity in question trol for possible spurious correlations between

were coded 1, and those who said that they parental school-involvement activities and

did not were coded 0. To eliminate simul- children’s outcomes. Each of these character-

taneity and time-order issues, I used data on istics has been shown elsewhere to be related

parents’ school involvement from 1996 to to both parents’ school involvement and chil-

predict children’s outcomes in 2000. While dren’s educational and behavioral outcomes.

the four items are correlated,10 multicollinear- The control variables are child’s race and gen-

ity diagnostics on the OLS regression models der (measured in a series of dummy vari-

suggested that including all four types of ables), child’s grade, type of child’s school,

involvement in one regression model does two-parent family, and family SES (created by

not introduce collinearity problems. taking the mean of the standardized logged

In addition, I used two child-reported vari- family income-to-needs ratio, mother’s and

ables to measure the effect of at-home father’s highest grade completed, and moth-

Downloaded from soe.sagepub.com at CARLETON UNIV on November 28, 2014

240 Domina

er’s and father’s occupational prestige level). the child’s prior score on the dependent vari-

Each of these controls was measured in 1996, able.

when the parental-involvement measures The base PIAT model indicates that several

were taken. parental-involvement activities are significant-

ly related to high academic achievement.

Prior Performance To assess the possible Attending parent-teacher conferences and

reciprocal causal relationship between PTA meetings, volunteering both in and out

parental involvement and children’s out- of the classroom, and checking homework

comes, I added measures to control for chil- are all positively associated with subsequent

dren’s prior performance on relevant assess- scores on academic achievement tests.

ments. With the addition of these prior per- Furthermore, these effects are not insubstan-

formance variables, the PIAT and BPI analyses tial: Children whose parents participated in

became time-lagged growth analyses. While each of these five involvement activities

the earlier models predict the effect of scored an average of 15.35 percentage points

parental involvement on children’s 2000 PIAT higher on the 2000 standardized composite

and BPI assessment values, these time-lagged PIAT examination. Homework help is nega-

models predict the change in assessment val- tively associated with academic achievement

ues over these four years. Controlling for prior in this model. The six parental involvement

values in the PIAT and BPI models reduces the variables explain less than 5 percent of the

model’s variability considerably; the students’ variance in PIAT scores. Nonetheless, this

1996 PIAT scores correlate with their 2000 model clearly shows that children with

scores at .72, and the 1996 BPI scores corre- involved parents tend to have higher acade-

late with the 2000 BPI scores at .65. mic achievement.

The second PIAT model suggests that

Interaction Effects some of this positive association between

parental involvement and academic achieve-

The final step of the analysis was to investi- ment is spurious. Attending PTA meetings,

gate heterogeneity in the effects of parental volunteering outside the classroom, and

involvement by parent’s SES, using interac- checking on homework are all significantly

tion terms created by multiplying the SES and positively associated with academic

scale by each of the parental-involvement achievement, even after race, family back-

activities. The two outcome variables were ground, and school sector are controlled.

then regressed on each of these interaction However, the coefficient for attendance at

terms, along with controls for SES and the parent-teacher conferences becomes nega-

other background and prior performance tive in this model, the coefficient for class-

controls. For clarity’s sake, each of these inter- room volunteering becomes statistically

action analyses was run separately. insignificant, and the positive and statistically

significant coefficients for attending PTA

meetings and volunteering outside the class-

FINDINGS room shrink considerably. Controlling for a

child’s background characteristics reveals that

Table 2 presents the effects of parental- at least some of the positive association

involvement activities in 1996 on children’s between each parental-involvement measure

academic achievement and behavioral prob- and academic achievement that was

lems in 2000. Three models are reported for observed in the base model is an artifact of

each dependent variable: The base model the mutual dependence of parental involve-

looks at the effects of parental involvement ment and academic achievement on back-

without any controls, the second addresses ground characteristics. Like much of the

the issue of spurious causality by controlling research on the link between parental

for the child’s socioeconomic background, involvement and academic achievement, the

and the third addresses the issue of time overall picture that emerges from the second

order and causal direction by controlling for PIAT model is ambiguous. Net of race and

Downloaded from soe.sagepub.com at CARLETON UNIV on November 28, 2014

Table 2. Unstandardized OLS Coefficients: Effect of 1996 Parental Involvement on 2000 PIAT and BPI Scores

2000 PIAT 2000 BPI

Variables 1 2 3 1 2 3

Parents attended one-on-one meeting with teacher, 1996 2.94* -3.99*** -1.21 1.81 2.78* 1.61

Parents attended PTA meeting, 1996 3.32*** 1.92*** .47 -2.38** -.56 .36

Parents volunteered in classroom, 1996 1.71* -.48 .37 -2.76*** -2.08** -.14

Parents volunteered outside the classroom, 1996 6.56*** 2.67*** .27 -5.34*** -3.58*** -1.82**

How often parents checked homework, 1996 .82*** 1.02*** -.34* -6.51** -.93*** -.39*

Leveling the Home Advantage

How often parents helped with homework, 1996 -2.16*** -1.61*** -.33* 2.79 .22 -.43*

Black 11.80*** -5.81*** -5.67*** -3.08***

Hispanic -5.02*** -1.00 -3.19* .57

Other -3.61*** -2.05** 1.36 2.17*

Male .59 .71 4.05*** .58

Dummy, child attended public school, 1996 -3.26*** -1.14* 6.57*** 4.91***

Dummy, child lived with mother and her spouse/partner, 1996 .80 .85 -5.29*** -2.69***

Child’s grade in 1996 -.15 -2.78*** .41 -.44*

Family SES, 1996 15.76*** 6.91*** -7.75*** -2.86***

PIAT, 1996 .90*** —

BPI, 1996 — .63***

Constant 51.38*** 62.78*** 19.61*** 63.17*** 58.42 21.86

Downloaded from soe.sagepub.com at CARLETON UNIV on November 28, 2014

Adjusted R2 .049 .294 .601 .019 .083 .435

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

241

242 Domina

family background, some parental-involve- background are controlled in the second

ment activities are positively related to acade- model. Net of controls, parents’ volunteering

mic achievement; others are negatively or in school (both inside and outside the class-

nonsignificantly related. room) and homework checking are strongly

But like most research on parental involve- associated with lower levels of childhood

ment, this second PIAT model fails to account behavioral problems. As was the case in the

for reciprocal causality between parental PIAT models, some of the association

involvement and achievement. In the third between involvement and BPI that was

and final model, I allowed for the possibility observed in the base model is spurious; net of

that parents will adjust their involvement background characteristics, the three signifi-

according to their children’s needs by adding cant parental-involvement variables are asso-

a control for a child’s 1996 PIAT score. The ciated with a decline in BPI of just 6.6 per-

coefficients reported in this model can be centage points. Nonetheless, the second BPI

understood as the effect of parental involve- model suggests that the independent influ-

ment on the rate of children’s improvement ence of parental-involvement activities on

in academic achievement between 1996 and children’s behavior is much clearer and

2000. In this model, the only parental- stronger than is the influence of parental

involvement practices that are significantly involvement on academic achievement.

associated with academic achievement— The third model confirms this point, show-

attending parent-teacher conferences, check- ing that parents’ volunteering outside school,

ing homework, and helping with home- homework checking, and homework help all

work—are negatively associated. This finding reduced children’s 2000 behavioral problems,

suggests that once the effect of prior acade- even after background variables and 1996 BPI

mic achievement on parents’ educational- scores were controlled. It is worth noting that

involvement activities is accounted for, the the effect of homework help on BPI has

positive association between involvement reversed to become statistically significant

and achievement melts away. It lends sup- and negative in this third model. In other

ports to McNeal’s (1999) contention that the words, although the first two models showed

link between parental involvement and chil- no relationship between homework help and

dren’s cognitive outcomes is tenuous. BPI, the third model shows that homework

Furthermore, it substantially challenges the help prevents children’s behavioral problems.

notion that parental involvement boosts chil- In sum, the observed effect of parental

dren’s academic achievement. Unless involvement on children’s behavioral prob-

parental-involvement programs improve the lems is relatively modest; together, the three

effectiveness of parental involvement, this significant parental-involvement variables

finding should raise serious questions about account for a change of 2.6 percentage

these initiatives’ efficacy as a strategy to points in the standardized BPI scale. Despite

improve students’ learning. the weak causal link between parental

The analysis of the effect of parental involvement and children’s cognitive devel-

involvement on children’s behavioral prob- opment, these analyses show that parental-

lems yields more encouraging results. In the involvement activities can be effective in pre-

base model, four of the six parental-involve- venting children’s problem behaviors. The

ment activities are associated with fewer effect of parental involvement on children’s

behavioral problems. This model demon- behavior seems to come primarily through

strates that children whose parents attend socialization and the exercise of social con-

PTA meetings, volunteer inside and outside trol.

the classroom, and check their homework The last question to be answered is

score 17 percentage points lower on the stan- whether the effects of parental involvement

dardized BPI distribution. vary on the basis of the parents’ socioeco-

Three of the four desirable parental- nomic background. Table 3 uses multiplica-

involvement effects remain significant after tive interaction terms to address this ques-

child’s school, family, and socioeconomic tion. It reports a series of two-step regressions

Downloaded from soe.sagepub.com at CARLETON UNIV on November 28, 2014

Leveling the Home Advantage 243

Table 3. OLS and Logistic Regression Coefficients: Heterogeneity in the Causal Effects of Parental

Involvement, by Parental SES (standard errors in parentheses)

2000 PIAT 2000 BPI

1 2 1 2

Parents Attended One-on-One Meeting, 1996 -1.19 -1.64 .53 1.29

(.77) (.84) (1.03) (1.12)

SES 7.00*** 8.70*** -2.91*** -5.84**

(.33) (1.29) (.42) (1.72)

Interaction — -1.78 — 3.06

(1.30) (1.74)

R-square .604 .604 .432 .432

Parents Attended PTA Meeting, 1996 .35 0.37 -.18 -.25

(.38) (.38) (.50) (.51)

SES 6.90*** 7.02*** -2.87*** -3.43***

(.33) (.47) (.42) (.62)

Interaction — -0.20 — .94

(.56) (.75)

R-square .604 .604 .432 .432

Parents Volunteered in the Classroom, 1996 .42 0.38 -.71 -.70

(.39) (.39) (.52) (.52)

SES 6.90*** 6.38*** -2.83*** -2.75***

(.33) (.50) (.42) (.64)

Interaction — 0.80 — -1.30

(.57) (.77)

R-square .604 .604 .432 .432

Parents Volunteered Outside the Classroom, 1996 .40 0.44 -1.66** -1.77**

(.40) (.40) (.53) (.53)

SES 6.91*** 7.70*** -2.77*** -5.00***

(.33) (.49) (.42) (.63)

Interaction — -1.25* — 3.59***

(.57) (.76)

R-square .604 .604 .433 .435

How Often Parents Checked Homework, 1996 -.52*** -0.48*** -.59*** -.56***

(.12) (.12) (.15) (.16)

SES 6.89*** 7.92*** -2.90*** -1.96*

(.33) (.72) (.42) (.95)

Interaction — -0.27 — -.24

(.17) (.22)

R-square .605 .605 .433 .433

How Often Parents Helped with Homework, 1996 -.50*** -0.52*** -.61*** -.57***

(.11) (.11) (.15) (.15)

SES 6.98*** 6.49*** -2.87*** -1.59*

(.33) (.57) (.42) (.75)

Interaction — .16 — -.42*

(.15) (.20)

R-square .605 .605 .434 .434

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Downloaded from soe.sagepub.com at CARLETON UNIV on November 28, 2014

244 Domina

predicting students’ 2000 PIAT and BPI scores—the statistically significant interaction

scores. In the first set of each of these models, terms suggest that the involvement activities

the dependent variable is regressed on a of low-SES parents have a more favorable

parental-involvement activity, SES, student’s influence on their children’s outcomes than

race and gender, school sector, family status, do the activities of high-SES parents.

grade, and score on the 1996 administration Table 4 illustrates this finding by calculating

of the outcome. In the second set of these the predicted outcome scores for each of the

models, an interaction term, created by mul- regressions in Table 3 that indicated significant

tiplying the parental-involvement variable interaction effects. This table compares the pre-

times family SES, is added. (For ease of inter- dicted effects of parental-involvement activities

pretation, only the involvement, SES, and for a hypothetical student whose parents’ SES is

interaction coefficients are reported here.) one standard deviation above the mean value

This table provides limited evidence that with the predicted parental-involvement effects

the effectiveness of parental involvement is for another hypothetical student whose par-

conditional on parental SES. Three of the 12 ents’ SES is one standard deviation below the

models reported here show statistically signif- mean. It shows that the PIAT return to parental

icant interactions between parental-involve- volunteering is nearly twice as high for low-SES

ment activities and SES. Two of these signifi- children as it is for high-SES children. Even

cant interactions point in a surprising direc- more striking is the effect of parental volunteer-

tion, in light of the evidence presented in ing on students’ BPI; while volunteering at

Desimone (2001), Lareau and Horvat (1999), school is associated with a small increase in

and McNeal (1999). With one exception— behavioral problems among affluent children; it

the significant negative interaction between substantially reduces behavioral problems

homework help and SES on children’s BPI among poor children.

Table 4. Predicted Values on Children’s Outcomes for Parental Involvementa

Parent Parent Did Not

Parental Involvement Participated Participate Difference

Outcome: 2000 PIAT

Volunteer outside the classroom

High SES 58.17 57.58 0.58

Low SES 49.66 48.50 1.16

Outcome: 2000 BPI

Volunteer outside of classroom

High SES 55.14 54.52 .62

Low SES 56.98 60.94 -3.96

Homework help

High SES 57.18 58.18 -1.00

Low SES 60.56 61.33 -.77

a These values were calculated by substituting values into the regression equations summarized

in Table 4. Predicted values were calculated for four hypothetical students: two students whose

values on the SES scale were one standard deviation above the mean, one whose parent partici-

pated in the parental-involvement activity and one whose parent did not, and two students whose

values on the SES scale were one standard deviation below the mean, one whose parent partici-

pated in the parental-involvement activity and one whose parent did not. For each of the remain-

ing predictors, sample means were substituted in the regression equation.

Downloaded from soe.sagepub.com at CARLETON UNIV on November 28, 2014

Leveling the Home Advantage 245

These findings are directly contrary to ed as a panacea—policy makers bill parental-

Lareau and Horvat’s (1999) qualitative analy- involvement initiatives as a tool to reform fail-

ses and McNeal’s (1999) quantitative analy- ing schools, improve students’ learning, and

ses, both of which suggested that the involve- reduce class- and race-based gaps in skills.

ment efforts of high-SES parents were more This study has suggested that some—but

effective than those of low-SES parents. In not all—of this faith may have been mis-

light of earlier research, the interactions placed. Attendance at parent-teacher confer-

reported here, which suggest that the ences, PTA membership, volunteering at

involvement of low-SES parents may pay school, homework checking, and homework

greater cognitive and behavioral dividends help are, indeed, associated with high scores

than the involvement of high-SES parents, on achievement tests and a low incidence of

should be regarded with caution. One impor- behavioral problems for elementary school

tant difference between my analyses and the children. However, after school and family

previous analyses may explain this difference: background and child’s prior academic

My analyses were time lagged to control for achievement are controlled, the effect of each

students’ prior achievement and therefore of these involvement activities on children’s aca-

separate the effect of socioeconomic back- demic achievement is negative or nonsignifi-

ground on the effectiveness of parental inter- cant. Rather than advance children’s cogni-

ventions from the confounding effect of its tive development, some forms of parental

academic and behavioral context. Thus, it is involvement may actually hurt. Although this

possible that earlier findings that showed finding is discouraging and difficult to recon-

greater parental-involvement returns for afflu- cile with the theoretical work that associated

ent students may have been biased by the involvement with academic advantages, it is

correlation between students’ skills and consistent with much of the previous research

behavior and their families’ SES and that on the link between parental involvement

these interactions show the true relationship and children’s cognitive outcomes.

between family SES and the effectiveness of By contrast, this study found a clear causal

parental-involvement activities. On the other link between parental involvement and chil-

hand, it is also possible that the interactions dren’s behavioral problems. Even after I

reported in Tables 3 and 4 simple reflect a applied stringent controls for children’s fami-

ceiling effect. If the children of highly ly and school backgrounds and scores on an

involved high-SES parents began the study earlier measure of behavioral problems, the

with optimal PIAT and BPI scores, they may analyses demonstrated that parents prevent

have experienced little change over the children’s behavioral problems when they vol-

course of the study, regardless of their par- unteer at school, help their children with their

ents’ school-involvement activities. homework, and check their children’s home-

work.

McNeal’s (1999) treatment of parental

DISCUSSION involvement as a form of social capital helps

to make sense of the contrast between the

The idea that parents can change their chil- demonstrated effectiveness of parental

dren’s educational trajectories by engaging involvement in the domain of children’s

with their children’s schooling has inspired a behavior and its relative ineffectiveness in the

generation of school reform policies. In the area of cognition. McNeal argued that

two decades since the Reagan administra- involved parents influence their children in

tion’s Goals 2000, parental involvement has three ways: First, they socialize their children

become a catchphrase in educational policy by demonstrating their interest in their chil-

making, and school outreach efforts, such as dren’s education (as they do when they pay

open houses, PTAs, and parent coordinators, close attention to their children’s homework).

have become increasingly common in U.S. Second, they exercise social control by spend-

elementary schools. In the public discourse, ing time at school, getting to know teachers

parental involvement has come to be regard- and other parents, and using these ties to

Downloaded from soe.sagepub.com at CARLETON UNIV on November 28, 2014

246 Domina

monitor their children’s schooling. Finally, may translate into cognitive advantages in

they gain access to insider information by the long run. As students progress through

meeting and sharing information with teach- school, their attitudes and behavior can have

ers, administrators, and other parents. For the important implications for their academic

first and second of these mechanisms, in par- engagement and success. For example,

ticular, the link between involvement and McLeod and Kaiser (2004) demonstrated that

children’s behavior is more direct than the young children’s behavior (as measured by

link between involvement and children’s cog- the BPI) influences their odds of later com-

nition. My findings are consistent with this pleting high school and enrolling in college.

analysis, showing that socializing activities Further research is needed to understand how

like homework help and checking and social parental-involvement activities that occur

control activities like school volunteering pre- when students are in elementary school pay

vent children’s behavioral problems, even off as students move into middle school, high

though they have little direct influence on school, and beyond.

academic achievement.

The findings in this article undermine the

traditional case for increasing parental involve- NOTES

ment in schools, suggesting that involvement

is ultimately unrelated to students’ academic 1. However, this is not the only way in

performance. It should be noted, however, which reciprocal causality can bias estima-

that the article did not directly assess the tions of the effect of parental involvement on

effectiveness of parental-involvement policies. children’s outcomes. Crosnoe’s (2001b) study

Although many of the parental-involvement of California high school students showed

activities that I studied likely took place in the that classroom success tends to stimulate the

context of schools’ parental-involvement ini- late high school involvement of parents

tiatives, many others took place in the whose children are enrolled in the noncollege

absence of programmatic intervention. This preparatory tracks.

distinction could have important implications 2. Because of the small sample size, I was

for the effectiveness of parental-involvement unable to replicate Desimone’s (2001) analy-

activities and should be examined more care- sis by race using the NLSY elementary school

fully in future research. On the one hand, children.

parental-involvement initiatives may improve 3. The NLSY79 is sponsored by the U.S.

the effectiveness of involvement by teaching Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor

parents how to intervene successfully in their Statistics and administered in collaboration

children’s schooling and by sensitizing school with the Center for Human Resource

personnel to parents’ needs. On the other Research, Ohio State University, and the

hand, if school-involvement programs flood National Opinion Research Center, University

schools with eager parents, they could dilute of Chicago.

the effectiveness of individual involvement 4. I used NLSY data only from 1996 to

activities. Unless school policies make 2000 because these are the only years for

parental-involvement activities more effective, which data on parents’ school involvement

the findings of this study suggest that they will are available.

do little to improve elementary school chil- 5. It should be noted, however, that even

dren’s learning. when weighted, this NLSY subsample should

However, the findings suggest a new, not be considered representative of all

more circumscribed, rationale for supporting American elementary school students.

parental-involvement programs: Involvement Instead, the children I analyzed are represen-

may do little to encourage students’ learning tative of the elementary school-aged children

in the short run, but it effectively prevents of all American women aged 35–42 in 2000.

students’ misbehavior. This is no small However, there is no evidence of any system-

achievement. The behavioral improvements atic difference between these children and all

that are associated with parental involvement elementary school children.

Downloaded from soe.sagepub.com at CARLETON UNIV on November 28, 2014

Leveling the Home Advantage 247

6. For each case that is missing, Amelia REFERENCES

generates five estimated values using data

from values on nonmissing variables and the Baker, Amy J. L., and Laura M. Soden. 1998. “The

EMis expectation maximization algorithm. Challenges of Parent Involvement Research”

The result is five separate data sets, in which (ERIC/CUE Digest No.134). Available on-line

nonmissing values remain unchanged (and at http://www.ericdigests.org/1998-3/par-

ent.html

are identical across data sets) and previously

Baker, Paula C., Canada K. Keck, Frank L. Mott, and

missing variables are filled.

Stephen V. Quinlan. 1993. NLSY Child

7. In models that I do not report here, I Handbook: A Guide to the 1986–1990 National

analyzed the three PIAT subtests separately; Longitudinal Survey of Youth Child Data.

the findings are substantively similar to the Columbus: Center for Human Resource

summary findings reported here. Research, Ohio State University.

8. One-month test-retest reliabilities vary Carey, Nancy, Laurie Lewis, Elizabeth Farris, and

between the three PIAT subtests, ranging from Shelley K. Burns. 1998. Parent Involvement in

.64 for the reading comprehension subtest to Children’s Education: Efforts by Public

.74 for the mathematics subtest and .89 for Elementary Schools (NCES 98-032).

Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing

the reading recognition subtest (Baker et al.

Office.

1993; Dunn and Markwardt 1970). The three

Catsambis, Sophia. 1998. “Expanding Knowledge

subtests scale well with one another—for the of Parental Involvement in Secondary

2000 subtests, Cronbach’s alpha = .83. Education: Effects on High School Academic

9. Although individual BPI items have low Success” (Report 27). Baltimore, MD: Center

test-retest reliability, scaled values have for Research on the Education of Students

proved to be more stable, with a one-month Placed at Risk, Johns Hopkins University.

test-retest reliability of .63 (Baker et al. 1993). Catsambis, Sophia, and Janet E. Garland. 1997.

The Cronbach’s alpha for the 28 2000 BPI “Parental Involvement in Students’ Education

items is .88. During Middle and High School” (Report 18).

Baltimore, MD: Center for Research on the

10. Volunteering in the classroom and vol-

Education of Students Placed at Risk, Johns

unteering outside the classroom are correlat- Hopkins University.

ed at .46. This is the highest correlation Catsambis, Sophia, and Belkis Suazo-Garcia. 2000.

between the four school-involvement vari- “Parents Still Matter: Parental Influence on

ables and the only correlation above the con- High School Seniors’ School-Related

ventional .4 threshold. Motivation, Future Plans, and Expectations.”

11. Variance inflation factors (VIF) were run Unpublished manuscript, Queens College,

on all the reported regression models and are City University of New York.

available on request. According to the rules of Chatterjee, Samprit, Ali S, Hadi, and Bertran Price.

thumb presented by Chatterjee, Hadi, and 2000. Regression Analysis by Example. New

York: John Wiley & Sons.

Price (2000), collinearity is an issue if any VIF

Chen, Xianglei, and Kathryn A. Chandler. 2001.

is greater than 10 and if the mean of all VIFs Efforts by Public K–8 Schools to Involve Parents

is considerably larger than 1. No VIF in the in Children’s Education: Do School and Parent

models reported here was greater than 2, and Reports Agree? (NCES 2001-076). Washington:

the mean VIFs for these models ranged from DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

1.28 to 1.30. Cohen, Jennifer Lynn. 2002. “The Effect of Parental

12. Adequately measuring parental Involvement on Academic Achievement in

involvement is a problem that is repeatedly Children Who Attended Head Start.”

encountered in the quantitative literature on Unpublished MSW thesis, California State

the consequences of parental involvement. University, Long Beach.

Comer, James P. 1980. School Power: Implications of

An ideal data set may provide measures of

an Intervention Project. New York: Free Press.

parental involvement from parents, students, Comer, James P., and Norris M. Haynes. 1991.

and teachers, as well as measures of the “Parent Involvement in Schools: An Ecological

intensity of involvement and information Approach.” Elementary School Journal

about the context of and motivations for 91:271–77.

parental-involvement activities. Crosnoe, Robert. 2001a. “Academic Orientation

Downloaded from soe.sagepub.com at CARLETON UNIV on November 28, 2014

248 Domina

and Parental Involvement in Education During Gootman, Elissa, 2003, August 30. “In Gamble,

High School.” Sociology of Education New York Schools Pay to Get Parents

74:210–30. Involved.” New York Times, p. A1.

—-. 2001b. “Parental Involvement in Adolescent Ho, Esther Sui-Chu and J. Douglas Willms. 1996.

Education: The Interplay of the School, “Effects of Parental Involvement on Eighth-

Community, and Ethnicity.” Sociological Focus Grade Achievement.” Sociology of Education

34:417–34. 69:126–41.

Desimone, Laura. 2001. “Linking Parent Honaker, James, Anne Joseph, Gary King, Kenneth

Involvement with Student Achievement: Do Scheve, and Naunihal Singh. 2001. Amelia: A

Race and Income Matter?” Journal of Program for Missing Data (Windows Version).

Educational Research 93:11–30. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. Available

Downey, Douglas B. 2002. “Parental and Family on-line at http://Gking.Harvard.edu

Involvement in Education.” Pp. 6.1–6.27 in Keith, Timothy Z. 1991. “Parent Involvement and

School Reform Proposals: The Research Evidence, Achievement in High School.” Advances in

edited by Alex Molnar. Tempe: Education Reading/Language Research 5:125–41.

Policy Studies Laboratory, Arizona State King, Gary, James Honaker, Anne Joseph, and

University. Kenneth Scheve. 2001. “Analyzing

Duncan, Greg J., and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn. 1997. Incomplete Political Science Data: An

Consequences of Growing Up Poor. New York: Alternative Algorithm for Multiple

Russell Sage Foundation. Imputation.” American Political Science Review

Dunn, Lloyd M., and Frederick C. Markwardt, Jr. 95:49–69.

1970. Peabody Individual Achievement Test Lareau, Annette. 1989. Home Advantage: Social

Manual. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Class and Parental Intervention in Elementary

Service. Education. London: Falmer.

Epstein, Joyce L. 1986. “Parents’ Reactions to Lareau, Annette, and Erin McNamara Horvat.

Teacher Practices of Parental Involvement.” 1999. “Moments of Social Inclusion and

Elementary School Journal 56:277–94. Exclusion: Race, Class, and Cultural Capital in

—-. 1987a. “Effects on Student Achievement of Family-School Relationships.” Sociology of

Teachers’ Practices of Parental Involvement.” Education 72:37–53.

Pp. 261-276 in Literacy Through Family, Mattingly, Doreen J., Radmila Prislin, Thomas L.

Community, and School Interaction, edited by McKenzie, James L. Rodriguez, and Brenda

Steven Silvern. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Kayzar. 2002. “Evaluating Evaluations: The

—-. 1987b. “Parent Involvement: What Research Case of Parent Involvement Programs.” Review

Says to Administrators.” Education and Urban of Educational Research 72:549–76.

Society 19:119–36. Mayer, Susan E. 1997. What Money Can’t Buy:

—-. 1992. “School and Family Partnerships.” Pp. Family Income and Children’s Life Chances.

1139–51 in Encyclopedia of Educational Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Research, edited by Marvin C. Alkin. New York: McLeod, Jane D., and Karen Kaiser. 2004.

Macmillan. “Childhood Emotional and Behavioral

—-. 2001. School, Family, and Community Problems and Educational Attainment.”

Partnerships: Preparing Educators and American Sociological Review 69:636–58.

Improving Schools. Boulder, CO: Westview McNeal, Ralph B., Jr. 1999. “Parental Involvement

Press. as Social Capital: Differential Effectiveness on

Fan, Xitao. 2001. “Parental Involvement and Science Achievement, Truancy, and Dropping

Students’ Academic Achievement: A Growth Out.” Social Forces 78:117–44.

Modeling Analysis.” Journal of Experimental Miedel, Wendy T., and Arthur J. Reynolds. 1999.

Education 70:27–61. “Parent Involvement in Early Intervention for

Fehrmann, Paul G., Timothy Z. Keith, and Thomas Disadvantaged Children: Does It Matter?”

Reimers. 1987. “Home Influence on School Journal of School Psychology 37:379–402.

Learning: Direct and Indirect Effects of Milne, Ann M., David E. Myers, Alvin S. Rosenthal,

Parental Involvement on High School and Alan Ginsburg. 1986. “Single Parents,

Grades.” Journal of Educational Research Working Mothers, and the Educational

80:330–37. Achievement of School Children.” Sociology of

Fine, Michelle. 1993. “[Ap]parent Involvement: Education 59:125–39.

Reflections on Parents, Power, and Urban Muller, Chandra. 1993. “Parent Involvement and

Public Schools.” Teachers College Record Academic Achievement: An Analysis of Family

94:682–710. Resources Available to the Child.” Pp. 77–114

Downloaded from soe.sagepub.com at CARLETON UNIV on November 28, 2014

Leveling the Home Advantage 249

in Parents, Their Children, and Schools, edited Components of Parental Involvement on

by Barbara Schneider and James S. Coleman. Eight-Grade Student Achievement: Structural

Boulder: Westview Press. Analysis of NELS-88 Data.” School Psychology

—-. 1998. “Gender Differences in Parental Review 24:299–317.

Involvement and Adolescents’ Mathematics Stevenson, David L., and David P. Baker. 1987.

Achievement.” Sociology of Education “The Family-School Relation and the Child’s

71:336–56. School Performance.” Child Development

Parcel, Toby, and Elizabeth G. Menaghan. 1994. 58:1348–57.

Parents’ Jobs and Children’s Lives. New York: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor

Walter de Gruyter. Statistics. 2001. The National Longitudinal

Reay, Diane. 1998. Class Work: Mothers’ Surveys Handbook 2001. Washington, DC:

Involvement in their Children’s Primary Author.

Schooling. London: UCL Press. Useem, Elizabeth. 1992. “Middle Schools and

Sanders, Mavis. 1998. “The Effects of School, Math Groups: Parents’ Involvement in

Family, and Community Support on the Children’s Placement.” Sociology of Education

Academic Achievement of African American 65:263–79.

Adolescents.” Urban Education 33:384–409. Wallace, Trudy, and Herbert J. Walberg. 1991.

Singh, Kusum, Patricia G. Bickley, Paul Trivette, “Parental Partnerships for Learning.”

Timothy Z. Keith, Patricia B. Keith, and Eileen International Journal of Educational Research

Anderson. 1995. “The Effects of Four 15:131–45.

Thurston Domina is a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at the Graduate School and University Center,

City University of New York. His dissertation investigates the causes and consequences of recent

increases in residential segregation between college graduates and people with lower levels of edu-

cation.

The author is grateful to Paul Attewell, David Lavin, and Julia Wrigley for their helpful comments on

earlier versions of this article. This research was supported by a Social Justice and Social Development

in Educational Studies training grant, codirected by Colette Daiute and Michelle Fine and funded by

the Spencer Foundation. Address correspondence to Thurston Domina, Ph.D. Program in Sociology,

CUNY Graduate Center, 365 Fifth Avenue, 6109, New York, NY 10016; e-mail: tdomina@gc.cuny.edu.

Downloaded from soe.sagepub.com at CARLETON UNIV on November 28, 2014

You might also like

- Parental Involvement To Their Child's Achievement Chapter 1 and 3Document15 pagesParental Involvement To Their Child's Achievement Chapter 1 and 3Kimberly MontalvoNo ratings yet

- Effects of Parental Involvement To The Academic Performance of Selected Grade 11 Humanities and Social Sciences StudentsDocument12 pagesEffects of Parental Involvement To The Academic Performance of Selected Grade 11 Humanities and Social Sciences StudentsCatherine Verano RosalesNo ratings yet

- KABUHIDocument39 pagesKABUHIJhoi Enriquez Colas PalomoNo ratings yet

- ACE Personal Trainer Manual: 5 EditionDocument20 pagesACE Personal Trainer Manual: 5 EditionAfraz Sk100% (1)

- Influence of Family Background On The Educational Development of Secondary School Students in Egor L.G.A. of Edo StateDocument58 pagesInfluence of Family Background On The Educational Development of Secondary School Students in Egor L.G.A. of Edo StateDaniel ObasiNo ratings yet

- Narrative WritingDocument28 pagesNarrative Writingputri01bali100% (1)

- Mathematics G9: Quarter 2Document40 pagesMathematics G9: Quarter 2Kyung Soo86% (7)

- The ProblemDocument27 pagesThe ProblemChapz Pacz100% (3)

- Class Record New Format For MAPEHDocument8 pagesClass Record New Format For MAPEHJo S EphNo ratings yet

- Parental InvolvementDocument27 pagesParental InvolvementSabeen Noman50% (2)

- Behavioral EconomicsDocument248 pagesBehavioral Economicskevin ostos julca100% (1)

- Niccolo Machiavelli's, The PrinceDocument6 pagesNiccolo Machiavelli's, The Princejahnavi taakNo ratings yet

- Masterfile ResearchDocument17 pagesMasterfile ResearchNaomi Aira Gole Cruz100% (1)

- Parents Matter: How Parent Involvement Impacts Student AchievementFrom EverandParents Matter: How Parent Involvement Impacts Student AchievementNo ratings yet

- Group 33 Activity 7 Chapter 2 of Research ProposalDocument11 pagesGroup 33 Activity 7 Chapter 2 of Research Proposaljasmin grace tanNo ratings yet

- Philippine LiteratureDocument6 pagesPhilippine Literatureemdyeyey84% (19)

- 186 FullDocument16 pages186 FullMark Joseph RabutazoNo ratings yet

- The How, Whom, and Why of Parents' Involvement in Children's Academic Lives. More Is Not Always BetterDocument39 pagesThe How, Whom, and Why of Parents' Involvement in Children's Academic Lives. More Is Not Always BetterStefana Catana0% (1)

- Grolnick 1994Document17 pagesGrolnick 1994Miftahul JannahNo ratings yet

- A Study On The Effects of Family Involvement On ChildrensDocument91 pagesA Study On The Effects of Family Involvement On ChildrensvudgufugNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 209.35.167.143 On Mon, 27 Mar 2023 06:53:13 UTCDocument15 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 209.35.167.143 On Mon, 27 Mar 2023 06:53:13 UTCrrbillonesNo ratings yet

- Promoting Parent Involvement: SophiaDocument26 pagesPromoting Parent Involvement: SophiaElaine Pimentel FortinNo ratings yet

- Pomerantz, E and Moorman, E. 2007. The How, Whom, and Why of PDocument38 pagesPomerantz, E and Moorman, E. 2007. The How, Whom, and Why of PelsaNo ratings yet

- Draft Heidi Gruber Final 8500Document31 pagesDraft Heidi Gruber Final 8500api-278333549No ratings yet

- Thomas Dominique Updatedexpositoryessay Orginal DraftDocument5 pagesThomas Dominique Updatedexpositoryessay Orginal Draftapi-280630392No ratings yet

- Research 2Document53 pagesResearch 2sheila rose lumaygayNo ratings yet

- Parents' Role in Enhancing The Academic Performance of Students in The Study of Mathematics in Tabuk City, PhilippinesDocument16 pagesParents' Role in Enhancing The Academic Performance of Students in The Study of Mathematics in Tabuk City, PhilippinesSherrie LynNo ratings yet

- Influence of Family Background On The AcDocument71 pagesInfluence of Family Background On The AcDavid UdohNo ratings yet

- Kadewole G&C Parental Involvement On Child Behaviour ProjDocument35 pagesKadewole G&C Parental Involvement On Child Behaviour ProjOmobomi SmartNo ratings yet

- Ines PDFDocument16 pagesInes PDFInes KrvavacNo ratings yet

- An Ecological Perspective On The Transition To Kindergarten: A Theoretical Framework To Guide Empirical ResearchDocument21 pagesAn Ecological Perspective On The Transition To Kindergarten: A Theoretical Framework To Guide Empirical ResearchAnonymous GR5SD5kNo ratings yet

- A Qualitative Study of A Parental Involvement Program in A K.8 Catholic Elementary SchoolDocument16 pagesA Qualitative Study of A Parental Involvement Program in A K.8 Catholic Elementary SchoolItsMeDennel PulmanoNo ratings yet

- Adams Family School Relationship ModelDocument51 pagesAdams Family School Relationship ModelMc Neal P. AlnasNo ratings yet

- Children and Youth Services Review: Bethanne M. Schlee, Ann K. Mullis, Michael ShrinerDocument8 pagesChildren and Youth Services Review: Bethanne M. Schlee, Ann K. Mullis, Michael ShrinerPryceNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Parent Education and Family Income On Child AchievementDocument7 pagesThe Influence of Parent Education and Family Income On Child AchievementCharlesNo ratings yet

- Family Involvement On Child's Education Among Preschool ParentsDocument13 pagesFamily Involvement On Child's Education Among Preschool ParentsIOER International Multidisciplinary Research Journal ( IIMRJ)No ratings yet

- Impact of Parental Involvement To The AcDocument26 pagesImpact of Parental Involvement To The AcAldrin Francis RamisoNo ratings yet

- Socialization Values and Parenting Practices As Predictors of Parental Involvement in Their Children's Educational ProcessDocument19 pagesSocialization Values and Parenting Practices As Predictors of Parental Involvement in Their Children's Educational ProcessAyuNo ratings yet

- Thomas Dominique UpdatedexpositoryessayDocument5 pagesThomas Dominique Updatedexpositoryessayapi-280630392No ratings yet

- PRACTICAL RESEARCH BPMXDocument8 pagesPRACTICAL RESEARCH BPMXErin Trisha Kristel GaspanNo ratings yet

- Barnard2004parental Involvement Elementary SchoolDocument24 pagesBarnard2004parental Involvement Elementary SchoolTeodora AtomeiNo ratings yet

- Research 1oDocument23 pagesResearch 1oMary CaballesNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document15 pagesChapter 1Denmark Simbajon MacalisangNo ratings yet

- Pbs 3Document6 pagesPbs 3hotdogbunNo ratings yet

- Updated Research Gian Trisha AlmazanDocument9 pagesUpdated Research Gian Trisha Almazangianalmazan31No ratings yet

- ResearchDocument3 pagesResearchMelissa SagaydoroNo ratings yet

- Aikens, N. L., & Barbarin, O. (2008) - Socioeconomic Differences in Reading Trajectories The Contribution of Family, Neighborhood, and School Contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100 (2), 235.Document17 pagesAikens, N. L., & Barbarin, O. (2008) - Socioeconomic Differences in Reading Trajectories The Contribution of Family, Neighborhood, and School Contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100 (2), 235.Jose Luis100% (1)

- Dissertation Topics Parental InvolvementDocument7 pagesDissertation Topics Parental InvolvementWriteMyPapersCanada100% (1)

- Pomerantz Et Al., 2007 - The How, Whom, and Why of Parents' Involvement in Children's Academic LivesDocument39 pagesPomerantz Et Al., 2007 - The How, Whom, and Why of Parents' Involvement in Children's Academic LivesAdriana BucurelNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document19 pagesChapter 2LIAJOY BONITESNo ratings yet

- Guad Chap 1Document8 pagesGuad Chap 1Jasper Kurt Albuya VirginiaNo ratings yet

- R PDFDocument6 pagesR PDFWong Tiong LeeNo ratings yet

- McCormick 2013 Parent Involvement PDFDocument25 pagesMcCormick 2013 Parent Involvement PDFMarieCris BautistaNo ratings yet

- Description: Tags: ch1Document65 pagesDescription: Tags: ch1anon-41257No ratings yet

- Home Situations and Its Effect On Students Academic PerformancesDocument7 pagesHome Situations and Its Effect On Students Academic PerformancesVilma SottoNo ratings yet

- The Involvement of Parents in The Education of Their Children in Zimbabwe's Rural Primary Schools: The Case of Matabeleland North ProvinceDocument7 pagesThe Involvement of Parents in The Education of Their Children in Zimbabwe's Rural Primary Schools: The Case of Matabeleland North ProvinceZidane AlfariziNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document27 pagesChapter 1HANNA GRACE PAMPLONANo ratings yet

- Xaba-M-I 2015 The Empowerment Approach To Parental Involvement in EducationDocument13 pagesXaba-M-I 2015 The Empowerment Approach To Parental Involvement in EducationInnoQyNo ratings yet

- AcademicsDocument16 pagesAcademicsYlin Frem MieNo ratings yet

- Learning Is A Product Not Only For Formal SchoolingDocument4 pagesLearning Is A Product Not Only For Formal SchoolingANITA M. TURLANo ratings yet

- Sheldon 2002Document17 pagesSheldon 2002elsaNo ratings yet

- More Than Grades: How Choice Boosts Parental Involvement and Benefits Children, Cato Policy Analysis No. 383Document16 pagesMore Than Grades: How Choice Boosts Parental Involvement and Benefits Children, Cato Policy Analysis No. 383Cato InstituteNo ratings yet

- AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE EFFECT OF POOR PARENTING ON THE CHILDREN AND THEIR ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE OF THEIR CHILDREN - A CASE STUDY IN EGOR LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OF EDO STATE - ProjectClueDocument10 pagesAN INVESTIGATION INTO THE EFFECT OF POOR PARENTING ON THE CHILDREN AND THEIR ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE OF THEIR CHILDREN - A CASE STUDY IN EGOR LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OF EDO STATE - ProjectCluecollins nzeribeNo ratings yet

- The Problem and Its BackgroundDocument12 pagesThe Problem and Its BackgroundMark VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Flouri Et Al-2004-British Journal of Educational PsychologyDocument13 pagesFlouri Et Al-2004-British Journal of Educational PsychologyAsif BalochNo ratings yet

- Effects of Family Educational Background, Dwelling and Parenting Style On Students' Academic Achievement: The Case of Secondary Schools in Bahir DarDocument11 pagesEffects of Family Educational Background, Dwelling and Parenting Style On Students' Academic Achievement: The Case of Secondary Schools in Bahir DarAristotle Manicane GabonNo ratings yet

- Involving Parents in the Common Core State Standards: Through a Family School Partnership ProgramFrom EverandInvolving Parents in the Common Core State Standards: Through a Family School Partnership ProgramNo ratings yet

- Bloom S Taxonomy in Practice - A Hierarchy of Thinking Skills v3Document1 pageBloom S Taxonomy in Practice - A Hierarchy of Thinking Skills v3Sofia SoutricNo ratings yet

- Transcript of AudioDocument3 pagesTranscript of AudiodiannpNo ratings yet

- Dian Natasya Putri (1903402061004) - Journalism - Softer News, Features and ReviewsDocument4 pagesDian Natasya Putri (1903402061004) - Journalism - Softer News, Features and ReviewsdiannpNo ratings yet

- Revisi Group 6th ABDUL AND QUEN VICTORIADocument3 pagesRevisi Group 6th ABDUL AND QUEN VICTORIAdiannpNo ratings yet

- Task UK 1Document1 pageTask UK 1diannpNo ratings yet

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Technology in Relationships - FindDocument13 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of Technology in Relationships - Findbrayanseixas7840No ratings yet

- Aboutb EQDocument1 pageAboutb EQdiannpNo ratings yet