Professional Documents

Culture Documents

J Ajo 2006 02 047

Uploaded by

Zuni TriyantiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

J Ajo 2006 02 047

Uploaded by

Zuni TriyantiCopyright:

Available Formats

PERSPECTIVE

Pathogenesis of Graves Ophthalmopathy:

Implications for Prediction, Prevention,

and Treatment

JAMES A. GARRITY, MD, AND REBECCA S. BAHN, MD

● PURPOSE: To review current concepts regarding the geting the IGF-1R or the TSHR, and preventing

pathogenesis of Graves ophthalmopathy (GO). We have connective tissue remodeling. (Am J Ophthalmol

presented this information in the context of potential 2006;142:147–153. © 2006 by Elsevier Inc. All rights

target sites for novel disease therapies. reserved.)

● DESIGN: Review of recent literature.

G

● METHODS: Synthesis of recent literature. RAVES DISEASE IS A COMMON DISORDER WITH AN

● RESULTS: Enlargement of the extraocular muscle bod- annual incidence in women of one per 1,000

ies and expansion of the orbital fatty connective tissues is population. In addition to hyperthyroidism, clin-

apparent in patients with GO. These changes result from ical involvement of the eyes develops in 25% to 50% of

abnormal hyaluronic acid accumulation and edema individuals with Graves disease.1 The annual incidence of

within these tissues and expanded volume of the orbital Graves ophthalmopathy (GO) in women is approximately

adipose tissues. Recent studies have suggested that the 16 in 100,000 and in men three in 100,000. Although

increase in orbital fat volume is caused by stimulation of some patients with GO experience only mild ocular

adipogenesis within these tissues. The orbital fibroblast discomfort, approximately 5% have severe ophthalmopa-

appears to be the major target cell of the autoimmune thy, including excessive chemosis, proptosis, or even loss of

process in GO. A subset of these cells is capable of vision.

producing hyaluronic acid and differentiating into mature The clinical symptoms and signs of GO can be ex-

adipocytes, given appropriate stimulation. In addition, plained mechanically by the discrepancy between the

orbital fibroblasts from patients with GO have been increased volume of the swollen orbital tissues and the

shown to display immunoregulatory molecules and to fixed volume of the bony orbit.1 The expanded orbital

express both thyrotropin receptors (TSHRs) and insulin- tissues displace the globe forward and impede venous

like growth factor 1 receptors (IGF-1Rs). Increased outflow from the orbit. These changes, combined with the

TSHR expression in the GO orbit appears to be the local production of cytokines and other mediators of

result of stimulated adipocyte differentiation. The acti- inflammation, result in pain, proptosis, periorbital edema,

vation of IGF-1R on orbital fibroblasts by immunoglobu- conjunctival injection, and chemosis.

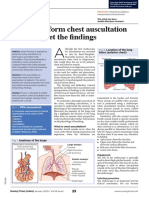

lins from GO patients results in increased production of Computed tomographic scans show that most patients

both hyaluronic acid and molecules that stimulate the with GO have enlargement of both the orbital fat com-

infiltration of activated T cells into areas of inflamma- partment and the extraocular muscles (Figure 1) and that

tion. others appear to have involvement of only adipose tissue

● CONCLUSIONS: Potential targets for novel therapeutic

(Figure 2) or extraocular muscle (Figure 3). The extraoc-

agents to be used in GO include blocking T-cell costimu- ular muscle cells are intact in early, active stages of the

lation, depleting B cells, inhibiting cytokine action, tar- disease, suggesting that they themselves are not the targets

Accepted for publication Feb 21, 2006. of autoimmune attack. Rather, the enlargement of the

From the Department of Ophthalmology (J.A.G.) and Division of extraocular muscle bodies results from an accumulation

Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism, Nutrition (R.S.B), Mayo Clinic, within the perimysial connective tissues of hydrophilic

Rochester, Minnesota.

Inquiries to James A. Garrity, MD, Department of Ophthalmology, glycosaminoglycans, especially hyaluronic acid, with atten-

Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905. dant edema.1 In later stages of the disease, the resolving

0002-9394/06/$32.00 © 2006 BY ELSEVIER INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. 147

doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2006.02.047

FIGURE 1. Computed tomographic scan of a 50-year-old FIGURE 2. Computed tomographic scan of a 43-year-old

woman with congestive Graves ophthalmopathy (GO) shows woman with Graves ophthalmopathy (GO) and marked prop-

mild enlargement of extraocular muscles and expansion of tosis related to expansion of the retrobulbar fat compartment

orbital fat compartment. (Top) Axial view. (Bottom) Coronal shows minimal enlargement of the extraocular muscles. Each

view. optic nerve is “straightened.” (Top) Axial view. (Bottom)

Coronal view.

inflammatory process within the muscles may leave them

fibrotic and with ocular misalignment. fibroblast constitutes the target cell. However, rather than

Severity of proptosis appears to be more closely related being a homogeneous population of cells, the fibroblasts

to the orbital adipose and connective tissue volume than exhibit remarkable phenotypic heterogeneity. One sub-

to muscle volume.2 This expanded adipose tissue volume population of these cells can produce hyaluronic acid and

results from both hyaluronic acid–related edema and the inflammatory prostanoids; other cells (termed “preadipo-

emergence of a population of newly differentiated fat cells cyte fibroblasts” or “preadipocytes”) can differentiate into

within these tissues.3 mature adipocytes. The former subpopulation is found in

In GO, the characteristic histologic changes within the connective tissues investing the extraocular muscles, and

orbital tissues outlined above suggest that the orbital the latter, the preadipocytes, is found primarily in the

148 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF OPHTHALMOLOGY JULY 2006

Fibroblasts also possess a wide array of tissue-specific

phenotypes, which likely affect the apparently selective

involvement of the skin of the anterior lower legs, termed

thyroid (“pretibial”) dermopathy. This condition is evi-

dent in approximately 15% of Graves patients having

severe GO and is much less common in Graves hyperthy-

roidism overall. Indeed, this finding is a clinical marker of

severe ophthalmopathy.5 The histologic changes in the

subdermal connective tissues in thyroid dermopathy ap-

pear similar to those within the GO orbit but without the

increase in adipose tissue volume.

Early studies of orbital fibroblasts focused on cytokines,

their effects on orbital fibroblasts biology, and phenotypic

differences between fibroblasts from the orbit and the

skin.1 For instance, orbital fibroblasts treated with inter-

feron-␥ or leukoregulin synthesize high levels of hyaluronic

acid, but similarly treated dermal fibroblasts produce only

small amounts.6 More recent studies have centered on the

particular sensitivity of orbital fibroblasts to the induction

of CD40 by interferon-␥ treatment. This receptor is an

important B-lymphocyte activator that is bound by

CD154, a receptor expressed at high levels by T lympho-

cytes. CD40/CD154 ligation causes fibroblasts to produce

several mediators of inflammation, including interleukin

(IL)-1, IL-6, and IL-8, and to synthesize high levels of

hyaluronic acid.7

Preadipocyte fibroblasts also show regional differences in

the expression of adipocyte-specific genes and vary in their

adipogenic potential; peroxisome proliferator-activated re-

ceptor (PPAR)-␥ agonists enhance differentiation of prea-

dipocyte fibroblasts from subcutaneous sites, but those from

omental sites are refractory to these agents.8 The study of

such depot-specific differences in fibroblast phenotype may

help to explain why patients with GO have expanded

orbital adipose tissues, without evidence of involvement of

other adipose tissue depots, and why the lower legs are

more commonly affected than are other skin regions.

In addition to these phenotypic differences between

fibroblasts, unique anatomic features of the orbit and lower

extremities appear to be clinically important in Graves

disease.9 The unyielding bony orbit predisposes to compres-

sion of low-pressure venous channels, increasing retrobulbar

FIGURE 3. Computed tomographic scan of a 58-year-old

pressure and periorbital edema. Similarly, prolonged standing

woman with profound visual loss from optic neuropathy in

association with Graves ophthalmopathy (GO) shows massive contributes to compromise of channels in the lower extrem-

enlargement of all extraocular muscles and apical compression ities, most likely contributing to the dependent edema seen in

of the optic nerves. Minimal fat is visible. (Top) Axial view. thyroid dermopathy. Moreover, individual anatomic vari-

(Bottom) Coronal view. ability, such as the shape of the orbits or variations in

venous or lymphatic vessels, may place some individuals

with Graves disease at special risk for the development of

severe GO or dermopathy.

orbital fat compartment. These phenotypic differences The close clinical relationship between Graves hyper-

between fibroblasts within the orbit may help to explain thyroidism and GO10 and the correlation between thyroid-

why some patients with GO have predominant eye muscle stimulating autoantibody levels and clinical activity of

disease (albeit with occasional evidence of fat accumula- GO11 suggest that immunoreactivity against thyrotropin

tion within the muscles) and others have expansion of the receptor (TSHR) may underlie both conditions. The

adipose tissue compartment as the major disease feature.4 concept that TSHR-expressing orbital adipose tissue may

VOL. 142, NO. 1 PATHOGENESIS OF GRAVES OPHTHALMOPATHY 149

be targeted in GO evolved from early studies showing phocytic infiltration, and the presence of TSHR immuno-

thyrotropin (TSH) binding to guinea pig adipose and reactivity within the orbital adipose tissues in the majority

retro-orbital tissues, or to porcine orbital connective tissue of immunized animals. Unfortunately, although the his-

membranes. The expression of this receptor in human fat topathologic findings appeared promising, none of the

tissue was first suggested by studies showing regulation of characteristic clinical signs of GO developed in the mice.

lipolysis by physiologic levels of TSH in human fetal and Of particular interest is a recent article by these authors in

newborn adipocytes but not in adult adipocytes.12 These which they questioned the validity of the thyroid and

results implicated TSH and its receptor in the normal ocular changes reported in their previous study.22 Never-

regulation of thermogenesis in early postnatal life. theless, the partial success of this model suggests that

A prerequisite for involvement of TSHR as an autoan- transfer of TSHR-primed T cells may hold potential for the

tigen in GO is that this protein be expressed in affected induction of ocular disease and supports the concept that

orbital tissues. Studies aimed at identifying TSHR in the TSHR may be an important orbital autoantigen.

orbital tissues have been performed by several laboratories Recent studies by Pritchard and associates23 demon-

using many different approaches. Results of these studies strated that fibroblasts from patients with Graves disease

were in general agreement and demonstrated the presence are activated by immunoglobulins (IgG) from these same

of TSHR mRNA and protein in orbital adipose tissue donors to synthesize molecules that stimulate the infiltra-

specimens and derivative cultures from patients with GO tion of activated T cells into areas of inflammation. This

and from patients without GO.13–15 However, additional process is mediated through the insulin-like growth factor

studies showed that levels of TSHR are in fact higher in 1 receptor (IGF-1R), suggesting that patients with GO

orbital adipose tissue from patients with GO than from have circulating autoantibodies directed against this recep-

patients without GO, suggesting that increased TSHR tor.24 The IgG-stimulated activation of this receptor does

expression in the orbit might be involved in disease not, however, appear to be restricted to fibroblasts from the

development.16 This concept is further supported by the orbit and pretibial skin because fibroblasts obtained from

finding of a positive correlation between GO patients’ diverse sites in these Graves patients behaved similarly.

TSHR mRNA levels in orbital adipose tissues excised These findings suggest that IGF-1R may represent a second

during decompression surgery and the patients’ clinical autoantigen in Graves disease, with an important role in

activity score.17 Similarly, TSHR appears to be more lymphocyte trafficking. The relatively restricted involve-

abundant in pretibial dermopathy than in normal pretibial ment of the orbit and pretibial skin in the extrathyroidal

skin.9 manifestations of Graves disease may be explained, in part,

A relationship between adipogenesis and TSHR expres- by the particular sensitivity of fibroblasts from these sites to

sion appears also to be present in cultures of orbital stimulation by cytokines and other immune factors.

preadipocyte fibroblasts undergoing in vitro differentiation. If one could predict the patients with Graves hyperthy-

Levels of TSHR mRNA, as well as leptin and adiponectin roidism in whom significant ocular complications would

mRNA (encoding genes expressed exclusively by mature develop, these patients could be offered early treatment

adipocytes, used here as markers of differentiation), are with agents not appropriate for patients at lower risk. In

approximately tenfold higher in cultures containing mature the future, skin biopsy specimens from patients with

adipocytes than in undifferentiated cultures.18,19 Similarly, Graves disease might provide useful information concern-

expression of these genes is increased in orbital adipose ing the activity in patients’ orbital tissues. However, for

tissue specimens from GO patients, compared with normal this predictive test to be developed, characteristics must be

tissue specimens, and significant positive correlations exist identified in these tissues or derivative cell cultures that

between mRNA levels corresponding to TSHR and those distinguish Graves patients who later develop GO from

encoding leptin and adiponectin.20 Taken together, these those who do not. Several in vitro responses of dermal

results suggest that adipogenesis is enhanced in the orbits fibroblasts from Graves patients have in fact been shown to

of patients with GO and that increased TSHR expression differ from normal, including the elaboration of immuno-

is a consequence of this process. modulatory molecules in response to treatment with

The only animal model of Graves disease in which Graves IgG.23 However, no feature described to date

ocular changes suggestive of GO have been reported was distinguishes subgroups of Graves patients with or without

developed by Many and associates.21 They transferred into GO. This supports the concept that environmental or

mice T cells from syngeneic animals that had been mechanical factors, such as tissue trauma or orbital shape

immunized with a TSHR fusion protein or vaccinated with and volume, may be important in ocular disease develop-

TSHR cDNA. Thyroiditis and anti-TSHR antibodies were ment.9

reported in these animals, but hyperthyroidism did not The advice to stop smoking forms the centerpiece of

occur and thyroid-stimulating autoantibodies were not patient counseling for prevention of GO. Current or

produced, limiting the study’s usefulness as an animal former smokers constitute 64% of Graves patients with

model of Graves disease. However, the authors described GO, 48% of those without overt GO, and only 28% of

tissue edema, dissociation of muscle fibers, minimal lym- healthy individuals.25 In addition, smoking is highly asso-

150 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF OPHTHALMOLOGY JULY 2006

months in 15% of the patients receiving radioiodine

therapy, in 2.7% of the patients receiving only antithyroid

drugs, and in none of the patients receiving both radioio-

dine and prednisone. Among the patients whose eye status

worsened after radioiodine therapy, 74% had preexisting

GO, and the majority were smokers. Although the eye

changes were largely mild and returned to baseline within

two to three months in 65% of the cases, eight patients

(5%) in the radioiodine group required additional therapy

for ocular disease. The authors concluded that any wors-

ening of GO after radioiodine therapy can be prevented by

concurrent treatment with corticosteroids and that this

should be considered in patients with preexisting GO,

especially if they are smokers.

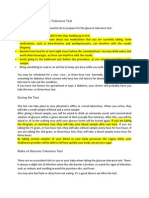

Several novel approaches to treatment of GO follow

logically from the current understanding of pathogenesis

(Figure 4). Studies from several laboratories underline the

FIGURE 4. Proposed targets for agents of potential benefit in pathogenic role of both Th-1–type and macrophage-de-

the treatment of Graves ophthalmopathy (GO) include (1) rived cytokines in early disease pathogenesis.31 Therefore,

blocking T-cell costimulation, (2) depleting B cells, (3) inhib- monoclonal antibodies that target proinflammatory cyto-

iting cytokine action, (4) targeting the insulin-like growth kines and chemokines might hold particular promise.

factor 1 (IGF-1) receptor or the thyrotropin (TSH) receptor, Specifically, biologic agents that block tumor necrosis

and (5) preventing connective tissue remodeling. IL-1, inter- factor (TNF)-␣ (infliximab, adalimumab, or etanercept) or

leukin 1; TNF-␣, tumor necrosis factor ␣. IL-1 receptor (anakinra) are attractive theoretical choices.

These agents are effective in rheumatoid arthritis and

Crohn disease therapy, and they are under investigation

ciated with the development of more severe GO,26 with for the treatment of such diverse conditions as uveitis,

the failure of immunosuppressive therapy,27 and with sarcoidosis, interstitial lung disease, graft-vs-host disease,

aggravation of GO after radioiodine therapy for thyrotox- and Sjögren syndrome. However, although these drugs

icosis. These effects do not appear to be related to have revolutionized the treatment of several immune-

behavioral changes associated with thyrotoxicosis or to mediated inflammatory diseases, there is growing evidence

differences in the age, gender, or educational background that TNF inhibition is associated with serious side effects.

of smokers compared with nonsmokers.26 Although mech- Of particular concern are several case reports of serious

anisms underlying this association remain unclear, contrib- infections, including the reactivation of Mycobacterium

utors may include effects of orbital hypoxia and the effect tuberculosis.32 In addition, lymphoma, demyelinating dis-

of free radicals in tobacco smoke on orbital fibroblast orders, hepatotoxicity, aplastic anemia, and a lupus-like

proliferation.28 Smokers have lower levels of IL-1 receptor syndrome have been described in association with TNF-␣

antagonists than do nonsmokers, which could adversely antagonists. In the future, the application of knowledge

affect the orbital disease process.29 Clearly, the strong concerning genetic variability and TNF/TNF receptor

association between smoking and GO holds important polymorphisms might aid in the targeting of anti–TNF-␣

clues to the pathogenesis of this disorder. therapy to patients most likely to benefit and least likely to

The use of prophylactic corticosteroids concurrently have adverse effects.

with radioiodine therapy for Graves hyperthyroidism has Mounting evidence for the participation of autoantibod-

also been reported to prevent the progression of GO in ies directed against TSHR and IGF-1R in GO11,24 suggests

patients with preexisting eye disease.10 The theoretical that blocking early phases of B-cell maturation involving

underpinning of this concept is that the destruction of CD20 ligation might be beneficial. A currently available

thyroid tissue by radioiodine may result in the release of biologic agent that might be studied in this regard is the

TSHR, which might augment the immune response di- anti–B cell agent rituximab. This agent, widely used in the

rected against this antigen on orbital cells. Indeed, levels of treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, is a chimeric mu-

TSHR-directed autoantibodies in the circulation have rine/human monoclonal antibody directed against the

been shown to increase immediately after radioiodine CD20 antigen found on the surface of normal and malig-

therapy.30 Bartalena and associates10 compared eye nant B lymphocytes. It is thought to act through induction

changes in hyperthyroid patients randomly assigned to of B-cell apoptosis and complement-mediated and anti-

receive radioiodine, methimazole alone, or both radioio- body-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. In a recent

dine and concurrent prophylactic prednisone. These in- trial of rituximab plus cyclophosphamide with or without

vestigators found that eye disease worsened within six prednisolone for treatment-resistant, erosive rheumatoid

VOL. 142, NO. 1 PATHOGENESIS OF GRAVES OPHTHALMOPATHY 151

arthritis, the combination of rituximab and cyclophosph- 2. Peyster RG, Ginsberg F, Silber JH, Adler LP. Exophthalmos

amide was well tolerated and optimally effective.33 Other caused by excessive fat: CT volumetric analysis and differ-

compounds that hold promise include costimulation inhib- ential diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1986;146:459 – 464.

itors, such as CTLA4-Ig or alefacept, that block the 3. Bahn RS. Clinical review 157: pathophysiology of Graves

ophthalmopathy: The cycle of disease. J Clin Endocrinol

“second signal” necessary for T-cell activation.34 By tar-

Metab 2003;88:1939 –1946.

geting this early step in the immune response, these agents

4. Smith TJ, Koumas L, Gagnon A, et al. Orbital fibroblast

hold the theoretical advantage of blocking both the heterogeneity may determine the clinical presentation of

production of autoantibodies and the secretion of inflam- thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab

matory cytokines. 2002;87:385–392.

Pharmacologic agents that block IGF-1 binding to its 5. Fatourechi V, Bartley GB, Eghbali-Fatourechi GZ, Powell

receptor or that target IGF-1R activation are potential CC, Ahmed DD, Garrity JA. Graves dermopathy and ac-

candidates for GO therapy because they could block the ropachy are markers of severe Graves ophthalmopathy.

effects of circulating IGF-1 receptor autoantibodies on Thyroid 2003;13:1141–1144.

orbital cells.23 These drugs are under active development 6. Smith TJ, Wang HS, Evans CH. Leukoregulin is a potent

because IGF can promote carcinogenesis. They include inducer of hyaluronan synthesis in cultured human orbital

anti–IGF-1R antibodies, small-molecule inhibitors of the fibroblasts. Am J Physiol 1995;268:C382–C388.

7. Sempowski GD, Rozenblit J, Smith TJ, Phipps RP. Human

IGF-1R tyrosine kinase, and fragments of antisense RNA.

orbital fibroblasts are activated through CD40 to induce

Other related approaches to GO therapy might include

proinflammatory cytokine production. Am J Physiol 1998;

targeting early phases of adipogenesis in orbital preadipo- 274:C707–C714.

cytes. If the differentiation of orbital preadipocytes could be 8. Adams M, Montague CT, Prins JB, et al. Activators of

blocked, disease manifestations resulting from increased adi- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ␥ have depot-

pose tissue volume within the orbit might be prevented.20 specific effects on human preadipocyte differentiation. J Clin

PPAR-␥ ligation is important in the initiation of adipogen- Invest 1997;100:3149 –3153.

esis, and PPAR-␥ agonists have been shown to stimulate 9. Rapoport B, Alsabeh R, Aftergood D, McLachlan SM.

both adipogenesis and TSHR expression in cultured orbital Elephantiasic pretibial myxedema: insight into and a hypoth-

preadiopocytes.19 Therefore, agents that might be devel- esis regarding the pathogenesis of the extrathyroidal mani-

oped to specifically block PPAR-␥ ligation would hold festations of Graves disease. Thyroid 2000;10:685– 692.

therapeutic promise for GO. Of related interest is a report 10. Bartalena L, Marcocci C, Bogazzi F, et al. Relation between

therapy for hyperthyroidism and the course of Graves oph-

of a patient with GO in whom increased proptosis devel-

thalmopathy. N Engl J Med 1998;338:73–78.

oped after treatment of diabetes mellitus type 2 with the 11. Gerding MN, van der Meer JW, Broenink M, Bakker O,

PPAR-␥ agonist rosiglitazone.35 Such thiazolidinedione Wiersinga WM, Prummel MF. Association of thyrotrophin

drugs that sensitize tissues to insulin through engagement receptor antibodies with the clinical features of Graves

of the PPAR-␥ receptor may thus be relatively contrain- ophthalmopathy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2000;52:267–271.

dicated in patients with GO. 12. Marcus C, Ehren H, Bolme P, Arner P. Regulation of

Useful information on the efficacy of any drug (or lipolysis during the neonatal period: importance of thyro-

combinations of therapeutic agents) in the treatment or tropin. J Clin Invest 1988;82:1793–1797.

prevention of GO can be gained only through prospective, 13. Heufelder AE, Dutton CM, Sarkar G, Donovan KA, Bahn

randomized double-masked trials. Such trials will likely RS. Detection of TSH receptor RNA in cultured fibroblasts

need to be large and multicentered if prevention of GO is from patients with Graves ophthalmopathy and pretibial

an end point, and they should be designed to ascertain dermopathy. Thyroid 1993;3:297–300.

14. Feliciello A, Porcellini A, Ciullo I, et al. Expression of

specific therapeutic benefits in relation to side effects and

thyrotropin-receptor mRNA in healthy and Graves disease

costs. Equally important will be the continued study of GO retro-orbital tissue. Lancet 1993;342:337–338.

pathogenesis and the immune system dysregulation initi- 15. Starkey KJ, Janezic A, Jones G, et al. Adipose thyrotrophin

ating the orbital disease process. From this information, receptor expression is elevated in Graves and thyroid eye

new approaches to prediction, prevention, or treatment of diseases ex vivo and indicates adipogenesis in progress in

GO will be developed. The promise of basic science vivo. J Mol Endocrinol 2003;30:369 –380.

research is that current treatment strategies involving 16. Bahn RS, Dutton CM, Natt N, et al. Thyrotropin receptor

surgery and immunosuppressive medications with serious expression in Graves orbital adipose/connective tissues: po-

side effects will be made obsolete. tential autoantigen in Graves ophthalmopathy. J Clin En-

docrinol Metab 1998;83:998 –1002.

17. Wakelkamp IM, Bakker O, Baldeschi L, Wiersinga WM,

Prummel MF. TSH-R expression and cytokine profile in

REFERENCES orbital tissue of active vs. inactive Graves ophthalmopathy

patients. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2003;58:280 –287.

1. Bahn RS, Heufelder AE. Pathogenesis of Graves ophthal- 18. Valyasevi RW, Erickson DZ, Harteneck DA, et al. Differen-

mopathy. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1468 –1475. tiation of human orbital preadipocyte fibroblasts induces

152 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF OPHTHALMOLOGY JULY 2006

expression of functional thyrotropin receptor. J Clin 27. Eckstein A, Quadbeck B, Mueller G, et al. Impact of smoking

Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:2557–2562. on the response to treatment of thyroid associated ophthal-

19. Valyasevi RW, Harteneck DA, Dutton CM, Bahn RS. mopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 2003;87:773–776.

Stimulation of adipogenesis, peroxisome proliferator-acti- 28. Burch HB, Lahiri S, Bahn RS, Barnes S. Superoxide radical

vated receptor-␥ (PPAR␥) and thyrotropin receptor by production stimuates retroocular fibroblast proliferation in

PPAR␥ agonist in human orbital preadipocyte fibroblasts. Graves ophthalmopathy. Exp Eye Res 1997;65:311–316.

J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:2352–2358. 29. Hofbauer LC, Muhlberg T, Konig A, Heufelder G, Schworm

20. Kumar S, Coenen MJ, Scherer PE, Bahn RS. Evidence HD, Heufelder AE. Soluble interleukin-1 receptor agonist

for enhanced adipogenesis in the orbits of patients with serum levels in smokers and nonsmokers with Graves oph-

Graves ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89: thalmopathy undergoing orbital radiotherapy. J Clin Endo-

930 –935. crinol Metab 1997;82:2244 –2247.

21. Many M-C, Costagliola S, Detrait M, Denef J-F, Vassart G, 30. Gamstedt A, Wadman B, Karlsson A. Methimazole, but not

Ludgate M. Development of an animal model of autoimmune betamethasone, prevents 131I treatment-induced rises in

thyrotropin receptor autoantibodies in hyperthyroid Graves

thyroid eye disease. J Immunol 1999;162:4966 – 4974.

disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1986;62:773–777.

22. Baker G, Mazziotti G, von Ruhland C, Ludgate M. Reeval-

31. Kumar S, Bahn RS. Relative overexpression of macrophage-

uating thyrotropin receptor-induced mouse models of Graves

derived cytokines in orbital adipose tissue from patients with

disease and ophthalmopathy. Endocrinology 2005;146:835–

Graves ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:

844.

4246 – 4250.

23. Pritchard J, Horst N, Cruikshank W, Smith TJ. Igs from

32. Ellerin T, Rubin RH, Weinblatt ME. Infections and anti-

patients with Graves disease induce the expression of T cell tumor necrosis factor ␣ therapy. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:

chemoattractants in their fibroblasts. J Immunol 2002;168: 3013–3022.

942–950. 33. Leandro MJ, Edwards JC, Cambridge G. Clinical outcome in

24. Pritchard J, Han R, Horst N, Cruikshank WW, Smith TJ. 22 patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with B lympho-

Immunoglobulin activation of T cell chemoattractant ex- cyte depletion. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:883– 888.

pression in fibroblasts from patients with Graves disease is 34. Kremer JM, Westhovens R, Leon M, et al. Treatment of

mediated through the insulin-like growth factor I receptor rheumatoid arthritis by selective inhibition of T-cell activa-

pathway. J Immunol 2003;170:6348 – 6354. tion with fusion protein CTLA4Ig. N Engl J Med 2003;349:

25. Bartalena L, Martino E, Marcocci C, et al. More on smoking 1907–1915.

habits and Graves ophthalmopathy. J Endocrinol Invest 1989; 35. Starkey K, Heufelder A, Baker G, et al. Peroxisome prolif-

12:733–737. erator-activated receptor-␥ in thyroid eye disease: contrain-

26. Prummel MF, Wiersinga WM. Smoking and risk of Graves dication for thiazolidinedione use? J Clin Endocrinol Metab

disease. JAMA 1993;269:479 – 482. 2003;88:55–59.

VOL. 142, NO. 1 PATHOGENESIS OF GRAVES OPHTHALMOPATHY 153

Biosketch

James A. Garrity, MD, completed his Ophthalmology training at Mayo Clinic before spending a fellowship year (orbital

diseases and neuro-ophthalmology) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, with John Kennerdell, MD. Dr Garrity returned to Mayo

Clinic in 1986 to join the staff. Currently, Dr Garrity’s practice interests are heavily biased toward orbital diseases and

Graves ophthalmopathy.

153.e1 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF OPHTHALMOLOGY JULY 2006

Biosketch

Rebecca S. Bahn, MD, obtained her MD from the Mayo Medical School and completed postgraduate training in internal

medicine and endocrinology at Mayo Clinic. She is currently a Professor of Medicine at Mayo Clinic College of Medicine,

Associate Chair of Internal Medicine and Associate Director of Research for Career Development, and Director of the

American Thyroid Association. Dr Bahn has an active clinical thyroidology practice and directs a research laboratory

studying the pathogenesis of Graves hyperthyroidism and ophthalmopathy.

VOL. 142, NO. 1 PATHOGENESIS OF GRAVES OPHTHALMOPATHY 153.e2

You might also like

- Stem Cells and Cell Signalling in Skeletal MyogenesisFrom EverandStem Cells and Cell Signalling in Skeletal MyogenesisNo ratings yet

- Assesment GODocument17 pagesAssesment GOBHUENDOCRINE SRNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Cell InjuryDocument21 pagesChapter 1 Cell Injuryhenna patelNo ratings yet

- Adipocyte Differentiation - From Fibroblast To Endocrine Cell2001Document8 pagesAdipocyte Differentiation - From Fibroblast To Endocrine Cell2001Reza AzghadiNo ratings yet

- Thyroid Eye Disease: Autoimmune Disorder Characterised by Infiltrative OrbitopathyDocument43 pagesThyroid Eye Disease: Autoimmune Disorder Characterised by Infiltrative OrbitopathyBIBI MOHANANNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Osteoarthritis: Johanne Martel-Pelletier PHDDocument3 pagesPathophysiology of Osteoarthritis: Johanne Martel-Pelletier PHDRachel DwiNo ratings yet

- CELL PathologyDocument28 pagesCELL PathologySaeed RazaqNo ratings yet

- Section 1: Cellular AdaptationsDocument30 pagesSection 1: Cellular AdaptationsElena PoriazovaNo ratings yet

- Occurrence of Tendon Pathologies in MetabolicDocument10 pagesOccurrence of Tendon Pathologies in MetabolicSebastián Jiménez GaticaNo ratings yet

- 6 CellularAdaptationsDocument87 pages6 CellularAdaptationsMaria MoiseencuNo ratings yet

- Section 1: Cellular AdaptationsDocument30 pagesSection 1: Cellular AdaptationsVirli AnaNo ratings yet

- Section 1: Cellular AdaptationsDocument30 pagesSection 1: Cellular AdaptationsAya KinugasaNo ratings yet

- Allergology International: Hironobu IhnDocument3 pagesAllergology International: Hironobu Ihncreyesdear3978No ratings yet

- Section 1: Cellular AdaptationsDocument30 pagesSection 1: Cellular Adaptationshaddi awanNo ratings yet

- Cytokines IN PeriodonticsDocument72 pagesCytokines IN PeriodonticsInduNo ratings yet

- BSE Viva v1.0 PDFDocument173 pagesBSE Viva v1.0 PDFKavivarma Raj RajendranNo ratings yet

- Bsmls 3A: Module 1: Growth Adaptations, Cellular Injury, and Cell DeathDocument7 pagesBsmls 3A: Module 1: Growth Adaptations, Cellular Injury, and Cell Death3A PEÑA AndreaNo ratings yet

- Regulation of Stem Cell Differentiation in Adipose Tissue by Chronic InflammationDocument13 pagesRegulation of Stem Cell Differentiation in Adipose Tissue by Chronic InflammationSindy Noreima Nino VegaNo ratings yet

- Steroid-Induced GlaucomaDocument15 pagesSteroid-Induced GlaucomaAnggitaNo ratings yet

- Multinodular Goiter Causes and Treatment OptionsDocument19 pagesMultinodular Goiter Causes and Treatment OptionsABDO ELJANo ratings yet

- CKD_Molecular Profiling Reveals a Common Metabolic Signature of Tissue FibrosisDocument27 pagesCKD_Molecular Profiling Reveals a Common Metabolic Signature of Tissue FibrosisCher IshNo ratings yet

- Hercules Baby - A Rare Case Presentation of Congenital MyopathyDocument4 pagesHercules Baby - A Rare Case Presentation of Congenital MyopathyInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Biological Aspect of Pathophysiology For Frozen ShoulderDocument9 pagesReview Article: Biological Aspect of Pathophysiology For Frozen ShoulderniekoNo ratings yet

- Aviezer2003 AcondroplastiaDocument13 pagesAviezer2003 Acondroplastiajossua carlosamaNo ratings yet

- Articular Cartilage and Changes in Arthritis An Introduction: Cell Biology of OsteoarthritisDocument7 pagesArticular Cartilage and Changes in Arthritis An Introduction: Cell Biology of OsteoarthritisBasheer HamidNo ratings yet

- 1-s2.0-S1063458422008536-mainDocument8 pages1-s2.0-S1063458422008536-mainabo_youssof20047438No ratings yet

- Cellular Adaptation-1Document8 pagesCellular Adaptation-1abdo100% (1)

- Keywords: Peripheral Giant Cell Granuloma/giant Cell Epulis, Jaw, ReactiveDocument4 pagesKeywords: Peripheral Giant Cell Granuloma/giant Cell Epulis, Jaw, ReactiveYeni PuspitasariNo ratings yet

- Platelet-Rich Plasma: Where Are We Now and Where Are We Going?Document8 pagesPlatelet-Rich Plasma: Where Are We Now and Where Are We Going?Nadira NurinNo ratings yet

- Clinical Manifestations and Management of Gaucher DiseaseDocument8 pagesClinical Manifestations and Management of Gaucher Diseasealejandro toro riveraNo ratings yet

- Androgens Modulate Interleukin-6 Production by Gingival FibroblastsDocument6 pagesAndrogens Modulate Interleukin-6 Production by Gingival FibroblastsDr.Niveditha SNo ratings yet

- Resorcion Condilar Idiopatica PDFDocument7 pagesResorcion Condilar Idiopatica PDFJuan Carlos MeloNo ratings yet

- Pujasari - Adaptation, Injury, & Death of CellsDocument24 pagesPujasari - Adaptation, Injury, & Death of CellsEfa FathurohmiNo ratings yet

- Cachexia - Pathophysiology and Clinical Relevance Morley2006Document9 pagesCachexia - Pathophysiology and Clinical Relevance Morley2006yuliaNo ratings yet

- Eosinophils in Vasculitis Characteristics - Khoury-Nrrheum.2014.98Document11 pagesEosinophils in Vasculitis Characteristics - Khoury-Nrrheum.2014.98Francisco Baca DejoNo ratings yet

- Prof. Dr. Noor Pramono, M.med, SC, SP - Og (K)Document29 pagesProf. Dr. Noor Pramono, M.med, SC, SP - Og (K)ponekNo ratings yet

- Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: SeminarDocument17 pagesCongenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: SeminarMaría Paula Sarmiento Ramón0% (1)

- IJPI_2(2)_61-63Document3 pagesIJPI_2(2)_61-63Tiara HapkaNo ratings yet

- Glucocorticoids Regulate Extracellular Matrix Metabolism in Human Vocal Fold Fibroblasts - Zhou - 2011 - The Laryngoscope - Wiley Online LibraryDocument4 pagesGlucocorticoids Regulate Extracellular Matrix Metabolism in Human Vocal Fold Fibroblasts - Zhou - 2011 - The Laryngoscope - Wiley Online Librarydr.hungsonNo ratings yet

- Defense Mechanisms of the GingivaDocument249 pagesDefense Mechanisms of the GingivaAssssssNo ratings yet

- Leptin Receptor Is Induced in Endometriosis and Leptin Stimulates The Growth of Endometriotic Epithelial Cells Through The JAK2/STAT3 and ERK PathwaysDocument9 pagesLeptin Receptor Is Induced in Endometriosis and Leptin Stimulates The Growth of Endometriotic Epithelial Cells Through The JAK2/STAT3 and ERK PathwaysDesyHandayaniNo ratings yet

- Scheja & Heeren 2019 The Endocrine Function of Adipose Tissues in Health and Cardiometabolic DiseaseDocument18 pagesScheja & Heeren 2019 The Endocrine Function of Adipose Tissues in Health and Cardiometabolic DiseasevibhutiNo ratings yet

- Adipose Tissue Remodeling in Lipedema: Adipocyte Death and Concurrent RegenerationDocument6 pagesAdipose Tissue Remodeling in Lipedema: Adipocyte Death and Concurrent RegenerationAlberto Martínez MartínNo ratings yet

- An Unusual Case of Idiopathic Spinal Epidural LipomatosisDocument5 pagesAn Unusual Case of Idiopathic Spinal Epidural LipomatosisAthenaeum Scientific PublishersNo ratings yet

- Semiquantitative Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis of Syndecan-1 and - 4 Messages in Cartilage and Cultured Chondrocytes From Osteoarthritic JointsDocument10 pagesSemiquantitative Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis of Syndecan-1 and - 4 Messages in Cartilage and Cultured Chondrocytes From Osteoarthritic Jointsinvestbiz optionstarNo ratings yet

- PompeDocument16 pagesPompeJuan Carlos Rivera AristizabalNo ratings yet

- KlotoDocument24 pagesKlotoyulian.stanevNo ratings yet

- Graves 508Document6 pagesGraves 508VellaNo ratings yet

- (2022) - Frozen Shoulder ReviewDocument16 pages(2022) - Frozen Shoulder ReviewCristobal LopezNo ratings yet

- Exploring Healthy Glial Cell and Neuron Interactions With Glioma and Associated Implications of Kynurenine PathwayDocument11 pagesExploring Healthy Glial Cell and Neuron Interactions With Glioma and Associated Implications of Kynurenine PathwayPaige MunroeNo ratings yet

- Adipose Organ Development and Remodeling (Cinti, 2018)Document75 pagesAdipose Organ Development and Remodeling (Cinti, 2018)VELEKANo ratings yet

- Manifestations of Systemic Diseases in the LarynxDocument6 pagesManifestations of Systemic Diseases in the LarynxIvan DarioNo ratings yet

- ArtrosisDocument8 pagesArtrosisAdrianNo ratings yet

- Obesity Is Associated With Macrophage Accumulation in Adipose TissueDocument13 pagesObesity Is Associated With Macrophage Accumulation in Adipose TissueRachel Lalaine Marie SialanaNo ratings yet

- Pathology (3) Adaptation and Cellular DepostitionDocument50 pagesPathology (3) Adaptation and Cellular Depostitionnurul dwi ratihNo ratings yet

- Obesity and Immune FunctionVF 19 - 20Document53 pagesObesity and Immune FunctionVF 19 - 20bmvdgxjwh7No ratings yet

- Thyroid Eye DiseaseDocument32 pagesThyroid Eye DiseaseGiorgos MousterisNo ratings yet

- Causes, Pathophysiology, & Teatment of PruritusDocument12 pagesCauses, Pathophysiology, & Teatment of PruritusJohnNo ratings yet

- Pseudoneoplasms of the GI TractDocument15 pagesPseudoneoplasms of the GI TractRudy AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Eosinofilos Glicobiologia Frontiers Medicine 2018Document12 pagesEosinofilos Glicobiologia Frontiers Medicine 2018Gustavo GomezNo ratings yet

- A Brief Review in Dental Management of Medically Compromised PatientsDocument7 pagesA Brief Review in Dental Management of Medically Compromised PatientsMishellKarelisMorochoSegarraNo ratings yet

- Assessment of CVSDocument46 pagesAssessment of CVSdileepkumar.duhs4817No ratings yet

- Mcqs - Biochemistry - Immune Response - PFMSG ForumDocument4 pagesMcqs - Biochemistry - Immune Response - PFMSG ForumDillu SahuNo ratings yet

- Kegawatdaruratan Bidang Ilmu Penyakit Dalam: I.Penyakit Dalam - MIC/ICU FK - UNPAD - RS DR - Hasan Sadikin BandungDocument47 pagesKegawatdaruratan Bidang Ilmu Penyakit Dalam: I.Penyakit Dalam - MIC/ICU FK - UNPAD - RS DR - Hasan Sadikin BandungEfa FathurohmiNo ratings yet

- Day Case Anaesthesia: Andrew Green MBBS, Fracgp GP Anaesthetist ANZCA RegistrarDocument50 pagesDay Case Anaesthesia: Andrew Green MBBS, Fracgp GP Anaesthetist ANZCA RegistrarSolape Akin-WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Assessment On Respiratory ProblemsDocument7 pagesAssessment On Respiratory ProblemsSetiaty PandiaNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Hypertension - The Mosaic Theory and Beyond - JURNALDocument17 pagesPathophysiology of Hypertension - The Mosaic Theory and Beyond - JURNALidham shadiqNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Nursing Test IiDocument44 pagesFundamentals of Nursing Test IiNOslipperyslopeNo ratings yet

- Praktek Essentials: Tanda Dan GejalaDocument5 pagesPraktek Essentials: Tanda Dan GejalaElvis HusainNo ratings yet

- MBBS Pathology MCQsDocument8 pagesMBBS Pathology MCQsShahzad Asghar Arain80% (5)

- Lesson Plan On RhinitisDocument15 pagesLesson Plan On Rhinitiskiran mahal100% (4)

- Preparing For A Glucose Tolerance TestDocument3 pagesPreparing For A Glucose Tolerance Testconnect.rohit85No ratings yet

- Management of Reproductive Health and DysmenorrheaDocument33 pagesManagement of Reproductive Health and DysmenorrheaIntan Permatasari Putri SNo ratings yet

- NCLEX Questions: Nursing Care, Medication Administration & Client EducationDocument3 pagesNCLEX Questions: Nursing Care, Medication Administration & Client EducationkxviperNo ratings yet

- FISA Engl DISCIPLINA FIZIOLOGIE I MODUL LIMBA ENGLEZADocument8 pagesFISA Engl DISCIPLINA FIZIOLOGIE I MODUL LIMBA ENGLEZAAbdallah Darwish100% (1)

- Treatment of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults Who Require Hospitalization - UpToDateDocument80 pagesTreatment of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults Who Require Hospitalization - UpToDateTran Thai Huynh NgocNo ratings yet

- © Kenneth Todar, PHD: (This Chapter Has 5 Pages)Document2 pages© Kenneth Todar, PHD: (This Chapter Has 5 Pages)sarahinaNo ratings yet

- Kursus Pementoran Dalam KejururawatanDocument40 pagesKursus Pementoran Dalam KejururawatanNajlaa RaihanaNo ratings yet

- Healing Cancer The Cayce WayDocument6 pagesHealing Cancer The Cayce WayXavier Guarch100% (2)

- Daftar PustakaDocument7 pagesDaftar Pustakarey whiteNo ratings yet

- NCP - Risk For Impaired Skin Integrity R/T Dry Skin and Behaviors That May Lead To Skin Integrity Impairment AEB Scratching of ScabsDocument1 pageNCP - Risk For Impaired Skin Integrity R/T Dry Skin and Behaviors That May Lead To Skin Integrity Impairment AEB Scratching of ScabsCarl Elexer Cuyugan Ano100% (4)

- Clinical Microscopy (Fecalysis)Document2 pagesClinical Microscopy (Fecalysis)Sheng Ramos AglugubNo ratings yet

- Symptoms of Ovarian CancerDocument3 pagesSymptoms of Ovarian Cancerwwe_jhoNo ratings yet

- Cayenne GuideDocument43 pagesCayenne GuideManuel Alejandro Hernández100% (2)

- Guidance Document - Nutritional Care & Support For TB Patients in India PDFDocument107 pagesGuidance Document - Nutritional Care & Support For TB Patients in India PDFekalubisNo ratings yet

- CPR Updated 2022Document32 pagesCPR Updated 2022Tathagata Bakuli100% (1)

- Philip J. Hashkes, Ronald M. Laxer, Anna Simon - Textbook of Autoinflammation-Springer International Publishing (2019)Document793 pagesPhilip J. Hashkes, Ronald M. Laxer, Anna Simon - Textbook of Autoinflammation-Springer International Publishing (2019)Marianna MoraesNo ratings yet

- AppendectomyDocument8 pagesAppendectomyDark AghanimNo ratings yet

- Question: 1 of 100 / Overall Score: 80%: True / FalseDocument84 pagesQuestion: 1 of 100 / Overall Score: 80%: True / FalseGalaleldin AliNo ratings yet

- Congenital Ureteropelvic Junction ObstructionDocument11 pagesCongenital Ureteropelvic Junction ObstructionAimee FNo ratings yet