Professional Documents

Culture Documents

ID 241 Symposium Magure K, Erskine C

Uploaded by

Moh SaadCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

ID 241 Symposium Magure K, Erskine C

Uploaded by

Moh SaadCopyright:

Available Formats

Merging Waves: The ‘learning conversations’ in worked based learning

and transformation into action

Authors: Chris Erskine and Kate Maguire

Key words: translating/interpreting; knowledge hermeneuts; action; habitus; transformation

Abstract

This paper, jointly authored by a candidate and an adviser, illustrates what underpins our

working alliance on a professional studies doctoral programme which makes it work. It

explores what both of us bring to the encounter; positionality and intentionality; the

importance of the conditions which need to be in place to support the co generation of

synthesised, distinctive or new knowledge; the skill of interpretation across difference; the

privileging of practice; an attitude of respect and the responsibility of research to the

communities in which we live. It is our intention that this attempt to explicate what actually

happens between us will contribute to thinking about the role of the adviser in this evolving

and exciting area of higher education which seeks to engage more fully with work practices

in a wide range of sectors.

Institute for Work Based Learning

College House

The Burroughs

London NW4 4BT

Tel +44 (0)20 8411 6118

Fax +44(0)20 8411 4551

www.mdx.ac.uk/wbl/

Chris Erskine cerskine@seedbedcontact.com 07786499891

Kate Maguire k.maguire@mdx.ac.uk 07748648356

1. THE ROAD OF A DPROF CANDIDATE

As introduction, I think it important to state that life, for me, started amongst narratives that

are played-out, in the cracks and holes of the structures of official society (Presdee 2000).

Home was found within the margins of historically determined and structurally unequal

contexts. I grew up in a working class, single parent household, which had seven children. In

these early formative years I developed a strong awareness to the issues of inequality. Many

of my earliest memories are related to themes connected to access and opportunity. For

example, the consequences of not having a father or any money; but also the benefits of a

very strong mother; three older sisters and three older brothers; and the wider Council estate

community network.

These and other circumstances developed my initial interest into issues concerning resource

distribution; representation; (self) advocacy and cultural politics. Hence looking back at the

development of my work-based learning, it should come as no surprise that I found real

meaning working amongst various marginalised groups. These places and experiences shaped

my very understanding of work, learning and subjectivity.

Having left school, at the age of sixteen with no academic achievements, meant my earliest

work experiences were found within low paid manual jobs. However by the age of eighteen I

started to work alongside people with learning disabilities in various community settings.

From this I went onto work with New Age travellers; homeless people and ultimately

community development initiatives within inner city contexts. All of these developments not

only strengthened my political critique of dominant norms, but I also began to recognise that

work could be seen more as a vocation than pay packet.

In summary, these dwelling places shaped my perspectives and values, giving me a strong

appreciation of the voice of the ‘Other’ and cultural contexts in which continual

reciprocation, opportunity and learning take place in the informal. In terms of political

positioning, I dwell within the social positions of left-libertarian movements, which have

resulted in me being weakly related to and specific organization and rejecting of authoritative

leadership figures as a matter of principles (Diani and Donati 1984). In other words I am

deeply sympathetic to anarchic philosophy and praxis.

2. WORK BASED LEARNING AND THE DPROF PROGRAMME

I shall now turn to consider the advantages of developing my work based learning via the

DProf at Middlesex. The focus of my studies is to explore the lifeworlds of activists, paying

particular attention to the issues of contradiction and incompleteness. My research proposal

suggests that:

I am embarking on a self-examination, in which I hope to dislodge and disrupt my

own lifeworld and work-based learning.

I am seeking to strengthen the ability of participants to appreciate, reflect and learn

from what they have achieved and how they have achieved it.

This will lead to a sharpened analysis of the environmental factors shaping their own

lifeworlds and the issues they most care for, the cultural incompleteness and

contradiction that they struggle with on a day-to-day basis.

This in turn shall create an invitation to explore the internal factors that shape their

lifeworlds and the consequent contradictions and incompleteness to be found in their

own identity.

Chris Erskine cerskine@seedbedcontact.com 07786499891

Kate Maguire k.maguire@mdx.ac.uk 07748648356

My decision to engage in the Work Based Learning at Middlesex is rooted in the strong

listening and learning culture underpinning the course ethos. I immediately recognised that

this ethos was very similar to my own working praxis within the context of urban social

movements. During my working life I have developed considerable and considered

experience in the third sector, working at the margins of society with those who are the most

disenfranchised. This work has been informed by the constant exploration of ideas about

personal autonomy; power; spontaneous ordering; equality and justice. These activities have

resulted in me being fluent in a number of domain dialects – the dialects of the street, the

academic, the advocate, the lobbyist and the political activist.

However it is important to point out that this has not left me in the position of 'the expert'. My

epistemology is one based in fragility and contradiction, in other words 'the more I know the

less I understand'. Similar to Bakhtin (2001) reflection upon:

Language exchanges are like mirrors that face each other, each reflecting in its own way a

piece, a tiny corner of the world. Thus we are forced to guess at and grasp for a world behind

mutually reflecting aspects that is broader, more multi-leveled, containing more and varied

horizons than would be available to a single language or single mirror.

Nonetheless, this awareness of partial, limited sight has not deterred me from seeking to

develop an approach of integrating grass root community development practice and academic

theory. In particular I have a strong connection with social movement, anarchic and narrative

theory. This has resulted in a commitment and conviction that activist and academic

traditions need to collaborate to initiate social and cultural change. It is this belief that has

brought me to embark on the DProf Programme.

3. DEVELOPING A LEARNING CULTURE

A key part of my ontology is a continuous journey of translation, interpretation and brokerage

within various community settings. It is my suggestion that these are the key characteristics

of any activist. As I have stated, within my Doctorate studies, I aim to explore the

contradictions and incompleteness within urban social movements, via the lives of activists.

This will entail a multi layered investigation into individual narratives and those of

government, funders, networks and projects.

The perspectives and values, discussed above, have positioned me to witness the access to

and distribution of resources between socio-demographic groups; and locate the creation of

sites of resistance, oppression(s) and alternative possibilities. Paul Lichtermann (1996: 227)

names this as ‘a translation ethic’:

A good translator has an obligation to the languages being translated and the cultures those

languages articulate. A good translator practices a kind of universalistic obligation, but one

grounded in specific cultures. A democratic community of diverse activists needs to translate

not only diverse political ideologies, but also definitions and practices of commitment itself.

By taking on a role of translator between political cultures, activists listen to the different

ways that movements maintain commitment and community.

In one sense the DProf will bring a discipline to my ‘insider action research’, which has no

clear beginning or, for that matter, ending point. Herr and Anderson (2005:36) state:

Research questions are often formalized versions of puzzles that practitioners have been

struggling with for some time and perhaps even acting on in terms of problem solving. The

Chris Erskine cerskine@seedbedcontact.com 07786499891

Kate Maguire k.maguire@mdx.ac.uk 07748648356

decision to do more systematic inquiry on a puzzling issue is one of asking what issue or

problem am I really trying to solve?

As my methodology shows, I aim to work in a collaborative manner using the de-centralizing

Multi-Site Action Research (MSAR) approach. This will enable ‘cross-site interactions’ that

‘are focused on information exchange and learning rather than on collaborative decision

making’. Such a framework will enable me to locate myself in the research position of an

‘insider in collaboration with other insiders’ (Herr and Anderson 2005). In that I will aim to

work alongside and in alliance with fellow activists.

Furthermore, MSAR presents a framework that connects extremely well with my personal

perspectives and values; and my current work-based learning culture. My vocational

activities entails continuous ‘cross-site interactions’, rather than ‘on-hand’ decision making.

To be aiming at working amongst activists within multi-site locations and multi-purpose

activities seems to be a very ‘natural’ thing to be doing.

Additionally, engaging in the DProf also resonates with Moore’s (2007: 35) personal needs of

embarking on action research:

I was probably in need of a mid-life upheaval in order to re-evaluate my personal priorities

and career direction. By undertaking research I suppose I was sub-consciously seeking to

assert my own autonomy and independence. After all, you don‟t do action research in order to

simply maintain the status quo. Without really realizing it, I think I must have seen the

undertaking of insider research as an opportunity to be self-directing, take the initiative and

redefine the nature of my relationship with my employer.

My final reflections of the advantages of engaging within the DProf require me to return to

my relationship with anarchic philosophy, theory and praxis. Colin Ward (1973: 8) writes:

Many years of attempting to be an anarchist propagandist have convinced me that we win

over our fellow citizens to anarchist ideas, precisely through drawing upon the common

experience of the informal, transient, self-organising networks of relationships that in fact

make the human community possible, rather than through the rejection of existing society as

a whole in favour of some future society where some different kind of humanity will live in

perfect harmony.

The DProf offers a real opportunity to approach anarchy via the ‘informal, transient, self-

organising networks of relationship’ that construct my work environment. I believe that there

is a real need for the concept of anarchy to be rethought and (re)considered within the private

and public, but particularly the academic sphere. Ward (ibid. :31) states that:

An important component of the anarchist approach to organisation is what we might call the

theory of spontaneous order: the theory that, given a common need, a collection of people

will, by trial and error, by improvisation and experiment, evolve order out of the situation –

this order being more durable and more closely related to their needs than any kind of

externally imposed authority could provide.

The DProf offers a clear opportunity to explore these ideas within the living narratives of

those that I work alongside. However, Diani & McAdam (2003:1) suggest, the identification

of such characteristic within an academic paper may prove far easier than the lifeworld of

activists, as such formulations takes place in a:

Chris Erskine cerskine@seedbedcontact.com 07786499891

Kate Maguire k.maguire@mdx.ac.uk 07748648356

String of more or less connected events, scattered across time and space; [that] cannot be

identified with any specific organization, rather consisting of various levels of formulation,

linked in patterns of inter-action.

The flexibility and rigor of the DProf Programme offers the perfect framework to engage in

such a sensitive journey of discovery. Nowhere is this better understood than with the

dynamic relationship that has developed between Kate and I. Central to both of us is a strong

desire to see a more just and equal society. However, this does not lead us to believe in some

'idealistic future', but more along the lines of what Valerie Fournier (2002: 192) identifies as:

utopianism rather than utopia, to emphasize movement over static visions of a better

order'..... it's about journey rather than destinations. It's about opening up visions of

alternatives, rather than closing down on a vision of a better future. It's about what moves us

to hope for and cultivate, alternative possibilities.

All that is stated above reflects the ingredient of the learning conversations that have taken

place between the two of us. These conversations have moved on through both authors

creating hermeneutic bridges between different realms of experience often requiring an

exploration of commonalities in dialects, trying on each others glasses, working through the

implications of change agency and the ethics of impact and caring.

4. THINKING ABOUT ADVISING

As Chris’s adviser and adviser to many other candidates over the years I often ask myself

what it is I do and how I do it beyond the contracting for time and contact. These are

important questions when I am also in the position of selecting and developing advisers in

this particular area of professional studies. I find myself saying to candidates, your consultant

is your specialist supervisor and I am, as your adviser, someone who works with you to take

care of the architecture of the piece which you want to create. I also ask my candidates those

two questions and they tell me various things: you listen, you challenge, you get interested,

you motivate, you map your way through our world which helps us map, you don’t take over,

you are there, you encourage us to be congruent with ourselves. It is very challenging to

explain what you do and how you do it when it is a way of being and thinking about the

world, when it is who you are now and who you are coming to be through your

interconnectedness with others and the world. So I will attempt this through my own

congruence using languages I have picked up and integrated on the way, those of social

anthropologist, psychotherapist, third sector worker and researcher.

Today we may talk of working at the interface of different domains, of co producing

knowledge, of transdisciplinary approaches to knowledge creation but these are not new.

They are a process of recovery from the differentiation of disciplines which most markedly

took place in the west in the eighteenth century in response to the specialist demands of a

rapidly evolving, capitalist society scientifically and technologically based. Like communities

on a land mass which fragment under the pressure of shifting tectonic plates, these

communities of theory and practice separated from the mothership, developed their own

languages, epistemologies, tribal systems, rituals and exclusive criteria for membership.

These islands themselves have archipelagic satellites in the form of organisations which in

turn develop their own mini cultures: some, entrusted with the resources of others, run amok

like some modern day Lord of the Flies (Golding 2005) scenario becoming increasingly

distant from values and community focussed responsibilities; others, strapped for cash, still

desperately try to uphold values without support. All have made significant impacts on the

way our world has evolved.

Chris Erskine cerskine@seedbedcontact.com 07786499891

Kate Maguire k.maguire@mdx.ac.uk 07748648356

Our movement to communicate, learn from and evolve knowledge through encounters and

reengagement with each other’s islands is not one of assimilation or colonialism but of

creativity, of catalysts that regenerate and originate in response to the stagnancy of a

managerialism which seeks to harness knowledge in functional bite size pieces to fit into pre

conceived templates that can be managed, measured, priced and sold. Central to our

movement is the communication between different realms of experience which has as its aim

not the hegemony of one tribe over the other but an encounter which is, among other things, a

prophylactic against stagnation and complacence. These islands are most comparable to

Bourdieu’s concept of habitus. Fiske (1992: 155) reminds us that

Bourdieu‟s theory of habitus allows the possibility of such movement [crossable and crossed ]

– we can after all, visit and live in habitats other than the one in which we are most at home.

But though some tourist excursions can give us some inside experience they can never

provide the same experience of these conditions as those who live or have lived in them.

For such encounters to have a chance of providing the conditions for new knowledge to

emerge, we need skilled interpreters, what I will call knowledge hermeneuts, the descendants

of Thoth and his later incarnation, Hermes Trismegistus. The ancient Egyptians appreciated

the boundaries of communication between different realms of experience and the skills

required for negotiation and progress. They recognised that they did not want to be gods and

the gods did not want to be human but that their co existence was core to a more fulfilled

existence for both. From such an observation emerged the embodiment of this complexity in

the form of Thoth, the interpreter god, a trickster, a builder, an artist, a scientist, a thinker, the

interplay of which was manifested in architecture, monuments of evolving complexity and

integrated knowledge. The pyramids of Thoth may look stagnant but they have challenged us

for millenia and we are still excited by them.

5. ATTRIBUTES OF A KNOWLEDGE HERMENEUT

Weaver

The notion of interpreter, or hermeneut is key to what defines the good school teacher, the

inspirational tutor, the informed manager, the enabling facilitator, the safe psychotherapist,

the professional coach. In professional studies, it is the capacity to be the knowledge

hermeneut that we look for in advisers for our candidates. The hermeneut listens, is

transparent about what he/she brings to the encounter, privileges the phronesis or practical

wisdom of the candidate, engages, seeks often through tricks to open up and be open to

knowledge connections the way neural pathways are stimulated and developed between

different areas of the brain. Living in our world, our world as the externalisation of the

nature of our brains influenced by both our biological inheritance and the transformed

dynamic of what we externalise, is a sometimes macabre, sometimes ecstatic, sometimes

quite ordinary dance which is played out at an individual level in the relationship between

candidate and adviser facilitating connections not only between other realms of knowledge

but between the disparate parts in the individual themselves.

Anthropologist

The knowledge hermeneut is also the anthropologist evolving from the ‘observer’, trying to

bracket off their own experience, to the ‘participant observer’ recognising the reflexivity

required to fully comprehend human impact on each other and the world, to the ‘advocate’

who can no longer separate themselves from what they have encountered once they have

Chris Erskine cerskine@seedbedcontact.com 07786499891

Kate Maguire k.maguire@mdx.ac.uk 07748648356

uncovered the internal connection which Bruns (1992:252) believes is a prerequisite for

understanding.

… basic to hermeneutics both ancient and modern is that idea that there is no making sense

at a distance; one must always work out some kind of internal connection with what one

seeks to understand.

The knowledge hermeneut can also be the ethnographer going through these different stages

of knowing with various candidates, all the time accumulating and processing these

knowledges in a form of ethnology which distils commonalities and differences from a range

of encounters and perspectives, a process which in itself contributes to new thinking.

And maps. I always find myself making maps of where I am with my candidates and as a

way to navigate through their world, their practice, their culture, their rituals, their

organisational frameworks, the different personalities, the impact of change, the threats and

opportunities. We compare our maps and the map of the outsider, who has perhaps seen the

shoreline from a different perspective and can bring stories of other cultures, can throw a

light on what is in shadow or reduce the size of a tribal god as it becomes set against a wider

terrain. Their maps improve as they signpost for me, the stranger, bringing more clarity for

themselves. We become each other’s guides.

Translator/interpreter/facilitator

To be a skilled knowledge hermeneut is an aspiration for me. The experiences I bring

personally and professionally to my encounters with a wide range of candidates on a

professional studies programme are those of my personal and professional lives. After many

years of visiting tribes I have found a home in professional studies, in this open space of

multiple languages and experiences, welcoming to all kinds of visitors willing to explore with

each other and with their advisers their various experiences then go on their way to pollinate

others with their evolving knowledge in an ever growing creative network. Here we meet the

American scientist drawn to Malaysia to learn about boat building who says he can never

look at science in the same way again; the designer of aeroplane wings which keep you and I

safe now questioning why the optimisation principles in engineering do not include a human

one; the hard working manager who wants to advocate change in her organisation to improve

the work environment finding rationales and solidarity among the many writers she would

never have known and accessed before; the unsung hero who has quietly dedicated twenty

years to widening participation in higher education at last finding his voice through a critical

reflection of his achievements; the woman who has brought dance, education and business

together rejoicing that she has managed to do so without compromising on the creativity and

spontaneity which define dance; my co author who weaves informed and creative

connections in a level of society which most of us only read about in the newspapers who

will leave with something which is still evolving.

Edifying conversationalist

How such individual changes take place which impact professional environments and how

new knowledge emerges is through what may be called learning conversations, or perhaps

more appropriately, edifying conversations (Rorty 1979: 360) as this stresses the enriching

potential of encounters between difference. Another attribute of a knowledge hermeneut can

be found in Rorty’s (1989:73) explication of the Aristotelian notion of ironist. Rorty sees the

ironist as fulfilling three conditions: someone who has ‘radical and continuing doubts’ about

her own vocabulary and is open to those of others, realises that ‘any arguments in her present

vocabulary cannot resolve the doubts’ and ‘does not think her vocabulary is closer to reality

than others’. To have an edifying conversation requires an openness to change, to synthesis,

to new chemical compounds and catalysts, to evolving vocabularies.

Chris Erskine cerskine@seedbedcontact.com 07786499891

Kate Maguire k.maguire@mdx.ac.uk 07748648356

Such conversations arrive at understanding aspects of each other’s culture, the fusion of

which generates something new. Such conversations are in fact, to borrow from Gadamer, the

very conditions of understanding. It is not about prescribing a procedure of understanding but

to clarify the conditions in which understanding takes place. (from Truth and Method cited in

Bruns p.12)

Listener

Listening is another attribute of the knowledge hermeneut which contributes to the edification

of each participant in the learning conversation, but not any kind of listening more a

Heideggerian notion of what happens when true listening occurs.

In true listening one enters not simply into another‟s subjectivity but into what is said… It

matters to Heidegger that in German the word for listening and hearing is also the word for

belonging. “We have heard (gehort),” Heidegger says, “when we belong (gehoren) to what

is said.” When one listens one steps out of the aggressive mode of grasping and knowing into

the mode of belonging (Bruns:157)

Added to this there is the type of active and reflecting back listening first brought to our

attention by Carl Rogers (1996). This listening is tuned into what is not said as much as to

what is said through an attitude of observation, respect and engagement of the heart and mind

which Bettelheim (1991) believed was at the core of understanding what we do and why we

do it. These forms of listening begin to access implicit or tacit knowledge and the trickster

encourages, among other things, various forms of metaphor enabling the articulation of what

is implicit.

Trickster

Trickster to many implies deception and in fact the later derivatives of Thoth, Hermes and

and Mercury, seemed to have lost the balance of their role as interpreters to become tools of

the gods who seemed eminently content with making a fool of mortals through cunning and

deceit no longer as a learning exercise for mutual and progressive co-existence but from the

will to dominate and be amused at the limitations of the ‘other.’ Little did the gods know that

this was a prelude to their annihilation, the end of an old paradigm. Trickster in the

hermeneutic sense is the story teller, the maker of parables, the skilled practitioner of

metaphors which Aristotle said was a natural human ability. Metaphors are in themselves

bridges of and to understanding. As a psychotherapist I have used metaphors with patients

who had survived such extreme experiences which everyday words could never hope to

convey, they were bridges they built for me to cross into their experience as safely as

possible. As an anthropologist I have been seeped in the metaphors of the meaning making

poetry of existence. So when I ask myself what it is I actually do with candidates I find

myself resisting a deconstruction, for what I do is fundamentally a part of me or who I have

come to be. It is through edifying conversations with candidates, colleagues, literature, people

of my past and present that I have come this far in trying to explain it without separating

myself from my autonomy and my own meaning making creativity which I see as always in a

dance with others.

Values

The knowledge hermeneut is an ethical practitioner as a way of being more than from

following a code of conduct. It is highly likely then that they will have a sense of justice,

balance and social responsibility. I am not saying that these are the prerequisites of a good

adviser/knowledge hermeneut only that they are in a sense an occupational hazard if one

meets the other with an openness to understanding and to belonging in the Heideggerian

Chris Erskine cerskine@seedbedcontact.com 07786499891

Kate Maguire k.maguire@mdx.ac.uk 07748648356

sense. Bruns (1992:263) sums this up well when talking about Whitman’s ethics of the open

road and Kateb’s explication of it

...as a readiness to convert tolerance to recognition; to admire and appreciate, especially

that which may be overlooked or despised; to acknowledge that one is not the only real thing

in the world, and that others are just as real to themselves...The effort to live outside oneself,

to lend oneself to the acknowledgement of other persons, to creatures and things, exists and

is underwritten by the sense that one is multiple, various, full of contradictions, full of moods

that „do not believe in each other‟.‟

In the knowledge hermeneut, one looks for the value of respect for the experience of others,

the value of seeking to engage and co create not to dominate and swallow up, the value of not

separating a human being from their autonomy and their creativity, the value of a

commitment to usefulness, to the idea of social responsibility and making a difference, the

value of respect for difference and to cooperate in solutions which are appropriate for the

habitus of other, not the habitus of that with which one is most familiar. I am reminded of a

story I heard many years ago when I was training as a psychotherapist which was used to

demonstrate the pitfalls of being a solution focussed therapist. I later found out that it was

most probably one of the wise tales originating in Africa. A writer was walking along the

road and saw a monkey jump from the tree into the river. It picked up a fish and placed it on

the tree. The writer asked the monkey, ‘What did you do that for?’ The monkey answered, ‘I

am saving the fish from drowning’.

This respect for practice, for difference, for new knowledge generated through cooperative

understanding and for the application of knowledge in fulfilment of social responsibility takes

not only individual academics out of their habitus but the whole university. In a recent soon

to be published paper by my colleague Professor Paul Gibbs called The Pragmatic University

he explores ideas about the university itself being the hub of social responsibility and change

through edifying conversations across different domains and habitats.

Coleman sees such a university as “an institution that in all its aspects is singularly

animated and concerned, rhetorically and practically, with the “solution” of the concrete

problems of societal development” (1986:477)… I will develop the specific category of

university, the pragmatic, where the notion of disciplinary no longer forms its legitimacy but

where knowledge is created in and through, but not restricted to, competences, capabilities,

practices and judgement in ways which shift the focus away from the epistemological

hegemony of disciplinary knowledge to ontology of praxis. I then consider this wider

application of the activities and actions of such universities in the workplace and their

realizing knowledge which is practical and relevant. Gibbs, 2011

I look forward to such a future for universities.

The conditions for new knowledge to emerge

If the conditions are right and I suggest edifying or learning conversations supported by the

skills and attributes of a knowledge hermeneut are essential conditions, then we will begin to

understand and co- generate new knowledge within an ethical frame which is defined by this

approach. The excitement then is not knowing yet what we will come to understand, what we

will come to know. Working with my co- author has taken me to islands I last visited as a

hippy wearing some very rose tinted glasses indeed. He has renewed my interest in anarchy

and social movements, his work reframes mine. I spoke to him of Gramsci, he contacted me

one day and said he had discovered Lacan. I had never thought that this would help him so

had never mentioned Lacan. This challenged me on the assumptions I had made about his

final vocabulary which were in fact the limitations of my own. Now he has taken Lacan to

Chris Erskine cerskine@seedbedcontact.com 07786499891

Kate Maguire k.maguire@mdx.ac.uk 07748648356

the level of an interpretive frame for his research on lack and fantasy, on the notion of

incompleteness, his synthesis not mine but one we have had edifying conversations about.

There is lack and fantasy in us all whether we look at that in a Lacanian frame or not.

Edifying conversations, which do not separate the participants from their creativity which

emerges out of the complexities of their knowingness, have the potential to fill the lack and

transform the fantasy into creative realities for the individual and for the islands they go on to

visit and inhabit.

Last word (for the moment)

And humour, do not forget a sense of humour, the ability to stand back and smile, have a

good laugh even, at some of the absurdities we deal with everyday and at some of the systems

which, rather than provide the conditions to nurture knowledge, restrict the art of laughing.

Humour too is a facilitator of learning and knowledge generation, it takes the focus away

from preoccupation with ‘I’ to the belongingness of ‘we’. The young know that very well and

as the future belongs to the young I thought I might leave the final word of this paper to an

insightful young man (Rosetti 2999:66) still at school who is part of a writing club which one

of our candidates runs to encourage self esteem, which he says also plays that role for him

too.

Having added the final brushstroke, I stepped back to gaze admiringly at my handiwork. I

had finished my painting. My masterpiece. Proudly I showed it to everyone within shouting

distance.

„The aim is encourage the viewer to question,‟ I told them.

„What is it‟? they asked.

„Exactly,‟ I said.

Bakhtin, M.M. ( 2001) Carnivalizing difference: Bakhtin and the other (Conference), 1993

Jan 2001, Routledge ppxvii, 265.

Bettelheim, B. (1991 The Informed Heart Penguin

Bruns, G. (1992) Hermeneutics Ancient and Modern Yale

Diani, M. and McAdam,D. (2003) Social Movements and Networks: relational approaches to

Collective Action, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Fiske, J. (1992) ‘Cultural Studies and the Culture of Everyday Life’ in Grossman, L., Nelson,

C., Treichler, P. Cultural Studies Routledge

Fournier, V. (2002) ‘Utopianism and the Cultivation of Possibilities: Grassroots movements

of hope’, in Parker,M. (ed.) Utopia and Organization . Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 189-

216.(ISBN: 1-4051-0072-9).

Gibbs, P. (2011) ‘The Pragmatic University’ due for publication. Contact p.gibbs@mdx.ac.uk

Golding, W. (2005) Lord of they Flies Faber and Faber

Herr, K. (2005) The action research dissertation : a guide for students and faculty. London:

SAGE.

Lichterman, P. (1996) The search for political community : American activists reinventing

commitment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moore, B. (2009) ‘Original sin and insider research’, Action Research. Volume 5(1): 27–39

Rogers, C. (1996) Way of Being Houghton Mifflin

Rorty, R. (1979) Philosophy and the mirror of nature. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rorty, R. (1989) Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Rossetti, S. (2009) The Finishing Touch in Bourbon Jottings Castle Welwyn Publishers

London

Ward, C. (1982) Anarchy in action. London: Freedom.

Chris Erskine cerskine@seedbedcontact.com 07786499891

Kate Maguire k.maguire@mdx.ac.uk 07748648356

You might also like

- Equity in Science: Representation, Culture, and the Dynamics of Change in Graduate EducationFrom EverandEquity in Science: Representation, Culture, and the Dynamics of Change in Graduate EducationNo ratings yet

- Queer Scholarly Activism: An Exploration of The Moral Imperative of Queering Pedagogy and Advocating Social ChangeDocument18 pagesQueer Scholarly Activism: An Exploration of The Moral Imperative of Queering Pedagogy and Advocating Social ChangeAbdelalim TahaNo ratings yet

- Social Justice Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesSocial Justice Literature Reviewc5qxzdj7100% (1)

- Beyond The Victim: The Politics and Ethics of Empowering Cairo's Street ChildrenFrom EverandBeyond The Victim: The Politics and Ethics of Empowering Cairo's Street ChildrenNo ratings yet

- Social Construction and Social Work Practice: Interpretations and InnovationsFrom EverandSocial Construction and Social Work Practice: Interpretations and InnovationsNo ratings yet

- Greene (2013) .Document11 pagesGreene (2013) .Pattylú Quintana Figueroa100% (1)

- Research As Community-Building Perspectives On TheDocument11 pagesResearch As Community-Building Perspectives On TheKinetiK GamingNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Social JusticeDocument5 pagesLiterature Review Social Justicerflciivkg100% (1)

- Smelser On Comparative Analysis Interdicsiplinarity and Internationalization in SociologyDocument15 pagesSmelser On Comparative Analysis Interdicsiplinarity and Internationalization in SociologyLuciana GandiniNo ratings yet

- Interdisciplinary Conversations: Challenging Habits of ThoughtFrom EverandInterdisciplinary Conversations: Challenging Habits of ThoughtRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Communities_of_PracticeDocument9 pagesCommunities_of_PracticeAvgoustinos TsaousisNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2 Dialogue On Action-Oriented ApproachesDocument2 pagesAssignment 2 Dialogue On Action-Oriented ApproachesMara GiannaNo ratings yet

- Collaborative Learning CommunitiesDocument19 pagesCollaborative Learning Communitiesapi-508733325No ratings yet

- Organizational Culture in Higher Education: Defining The EssentialsDocument8 pagesOrganizational Culture in Higher Education: Defining The EssentialsCR EducationNo ratings yet

- Equipping Technical Communicators for Social Justice Work: Theories, Methodologies, and PedagogiesFrom EverandEquipping Technical Communicators for Social Justice Work: Theories, Methodologies, and PedagogiesRebecca WaltonNo ratings yet

- Integral Communication by Adam B. LeonardDocument182 pagesIntegral Communication by Adam B. Leonardkabaij8124No ratings yet

- Simon-Roger-Empowerment As A Pedagogy of PossibilityDocument13 pagesSimon-Roger-Empowerment As A Pedagogy of PossibilityFelipe AristimuñoNo ratings yet

- Andreotti Focus19Document21 pagesAndreotti Focus19leniNo ratings yet

- Sociology Education Dissertation IdeasDocument8 pagesSociology Education Dissertation IdeasProfessionalCollegePaperWritersFrisco100% (1)

- TBW Paper 1Document6 pagesTBW Paper 1api-651919661No ratings yet

- Communication, Culture and Social Change: Meaning, Co-option and ResistanceFrom EverandCommunication, Culture and Social Change: Meaning, Co-option and ResistanceNo ratings yet

- Inquiry Placemat RevisedDocument6 pagesInquiry Placemat RevisedRebecca WalzNo ratings yet

- Person-Centered Arts Practices with Communities: A Pedagogical GuideFrom EverandPerson-Centered Arts Practices with Communities: A Pedagogical GuideRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Maclennan 2010Document306 pagesMaclennan 2010高诣鑫No ratings yet

- Conceptual Frameworks for Giftedness and Talent Development: Enduring Theories and Comprehensive Models in Gifted EducationFrom EverandConceptual Frameworks for Giftedness and Talent Development: Enduring Theories and Comprehensive Models in Gifted EducationNo ratings yet

- Getting to the Heart of Science Communication: A Guide to Effective EngagementFrom EverandGetting to the Heart of Science Communication: A Guide to Effective EngagementRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Chapter 1 Interncultural Business MangementDocument62 pagesChapter 1 Interncultural Business MangementEnrico BuzziNo ratings yet

- Symbolic Interaction and OrganizationalDocument18 pagesSymbolic Interaction and Organizationalbulan cahyaniNo ratings yet

- Social Service Research Paper TopicsDocument6 pagesSocial Service Research Paper Topicsp1zajywigyd2100% (1)

- Kemmis, S., & Mctaggart, R. (1988) - The Action Research Planner (3Rd Ed.) - Geelong: Deakin University PressDocument6 pagesKemmis, S., & Mctaggart, R. (1988) - The Action Research Planner (3Rd Ed.) - Geelong: Deakin University PressCarolina RojasNo ratings yet

- Innovations in Narrative and Metaphor: Methodologies and PracticesFrom EverandInnovations in Narrative and Metaphor: Methodologies and PracticesNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Topics in Community DevelopmentDocument6 pagesDissertation Topics in Community DevelopmentPaperWritingServicesLegitimateCanada100% (1)

- Assessment - 1 IntegrityDocument6 pagesAssessment - 1 IntegrityTommy HeriyantoNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 1Document27 pagesJurnal 1nabila ukhaNo ratings yet

- Considering More Feminist Participatory ResearchDocument13 pagesConsidering More Feminist Participatory ResearchACNNo ratings yet

- Tyler Branson Teaching Philosophy February 2014Document1 pageTyler Branson Teaching Philosophy February 2014TylerSBransonNo ratings yet

- New Strategies for Social Innovation: Market-Based Approaches for Assisting the PoorFrom EverandNew Strategies for Social Innovation: Market-Based Approaches for Assisting the PoorNo ratings yet

- Negotiating Power and Politics in Practitioner Inquiry CommunitiesDocument12 pagesNegotiating Power and Politics in Practitioner Inquiry CommunitiesMariusNo ratings yet

- Being an Interdisciplinary Academic: How Institutions Shape University CareersFrom EverandBeing an Interdisciplinary Academic: How Institutions Shape University CareersNo ratings yet

- Social Work Practice: Concepts, Processes, and InterviewingFrom EverandSocial Work Practice: Concepts, Processes, and InterviewingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Sample Dissertation SociologyDocument7 pagesSample Dissertation SociologyApaPapersForSaleSingapore100% (1)

- Contemporary Society Through the Lens of Applied Ethics: Observations from the Slippery Slope-Volume IFrom EverandContemporary Society Through the Lens of Applied Ethics: Observations from the Slippery Slope-Volume INo ratings yet

- Management and Morality: An Ethnographic Exploration of Management Consultancy SeminarsFrom EverandManagement and Morality: An Ethnographic Exploration of Management Consultancy SeminarsNo ratings yet

- Participatory Action ResearchDocument8 pagesParticipatory Action ResearchRashmila ShakyaNo ratings yet

- Cultures in Organizations Three Pers - .Document518 pagesCultures in Organizations Three Pers - .Farid ToofanNo ratings yet

- British Educational Research Journal, Vol. 28, No. 2, 2002Document13 pagesBritish Educational Research Journal, Vol. 28, No. 2, 2002Sharmeen IsmailNo ratings yet

- Elisheva Sadan EmpowermentDocument350 pagesElisheva Sadan EmpowermentJohana SvobodovaNo ratings yet

- Sociology Dissertation QuestionsDocument7 pagesSociology Dissertation QuestionsDoMyPaperForMoneyDesMoines100% (1)

- Research Paper On Human BehaviorDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Human Behavioregya6qzc100% (1)

- Martin, Joanne - Cultures in Organizations - Three Perspectives-Oxford University Press, USA (1992)Document516 pagesMartin, Joanne - Cultures in Organizations - Three Perspectives-Oxford University Press, USA (1992)nhanthuyNo ratings yet

- Agency As Collectivity Community Based Research For Educational EquityDocument12 pagesAgency As Collectivity Community Based Research For Educational EquityDeisy GomezNo ratings yet

- On Ethics, Diversity, and Conflict: The Graduate Years and Beyond, Vol. IFrom EverandOn Ethics, Diversity, and Conflict: The Graduate Years and Beyond, Vol. INo ratings yet

- Social Justice-Task StreamDocument6 pagesSocial Justice-Task Streamapi-275969485No ratings yet

- ID 239 Wittink JDocument18 pagesID 239 Wittink JMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- Social Implication of The InternetDocument31 pagesSocial Implication of The InternetlucasNo ratings yet

- Front MatterDocument12 pagesFront MatterMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- Value Conflicts and Social Choice in Electronic Funds Transfer System - 1978Document16 pagesValue Conflicts and Social Choice in Electronic Funds Transfer System - 1978Moh SaadNo ratings yet

- ID 134 Hauptmann S, Schulz K-PDocument19 pagesID 134 Hauptmann S, Schulz K-PMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- ID 256 Verzelloni LDocument16 pagesID 256 Verzelloni LMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- ID 227 Gronning TDocument11 pagesID 227 Gronning TMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- ID 149 Hoarau-Heemstra HDocument14 pagesID 149 Hoarau-Heemstra HMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- ID 106 Bouty I, Gomex M-LDocument12 pagesID 106 Bouty I, Gomex M-LMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- Quantitative RiskDocument22 pagesQuantitative RiskMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- ID 106 Bouty I, Gomex M-LDocument12 pagesID 106 Bouty I, Gomex M-LMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- Implementing Electronic Commerce in SMEs-three Case Studies - 1999Document15 pagesImplementing Electronic Commerce in SMEs-three Case Studies - 1999Moh SaadNo ratings yet

- Internet Adoption Barriers For Small Firms in The Netherlands - 2000Document12 pagesInternet Adoption Barriers For Small Firms in The Netherlands - 2000Moh SaadNo ratings yet

- B2B Model Performance AustraliaDocument19 pagesB2B Model Performance AustraliaMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- Relative SizeDocument20 pagesRelative SizeMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- Business Model Design and The Performance of Entrepreneurial FirmsDocument48 pagesBusiness Model Design and The Performance of Entrepreneurial FirmsMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- B2b EMarketplaces A Classification Framework To Analyse Business Models and Critical Success FactorsDocument21 pagesB2b EMarketplaces A Classification Framework To Analyse Business Models and Critical Success FactorsMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- Smes - Observatory - 2003 - Report4 - en - EOURPEDocument67 pagesSmes - Observatory - 2003 - Report4 - en - EOURPEMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- Arti Systematic ReviewDocument13 pagesArti Systematic ReviewHeriberto Gutierrez LopezNo ratings yet

- Pedley 2007Document4 pagesPedley 2007Moh SaadNo ratings yet

- Measuring E-Commerce Success - ApplyingDocument17 pagesMeasuring E-Commerce Success - ApplyingMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- Kanungo - 2004Document11 pagesKanungo - 2004Moh SaadNo ratings yet

- Business Solutions Report EnglishDocument108 pagesBusiness Solutions Report EnglishRamez AhmedNo ratings yet

- E-Commerce and Its Impact On Operations 20160621-32565-1uoe8f5 PDFDocument13 pagesE-Commerce and Its Impact On Operations 20160621-32565-1uoe8f5 PDFRicardo SevillaNo ratings yet

- Smes - Observatory - 2003 - Report4 - en - EOURPEDocument67 pagesSmes - Observatory - 2003 - Report4 - en - EOURPEMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- Automated Mechanism Design For B2B Ecommerce ModelsDocument6 pagesAutomated Mechanism Design For B2B Ecommerce ModelsMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- A Data Integration Framework For E-Commerce Product ClassificationDocument15 pagesA Data Integration Framework For E-Commerce Product ClassificationMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- B2b EMarketplaces A Classification Framework To Analyse Business Models and Critical Success FactorsDocument21 pagesB2b EMarketplaces A Classification Framework To Analyse Business Models and Critical Success FactorsMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- Mini Marketing Plan For Comcast Cable 1309382047Document15 pagesMini Marketing Plan For Comcast Cable 1309382047Moh SaadNo ratings yet

- B2B ECommerce An Empirical Investigation of Information Exchange and Firm PerformanceDocument21 pagesB2B ECommerce An Empirical Investigation of Information Exchange and Firm PerformanceMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- Financial Regulation A Transatlantic PerspectiveDocument376 pagesFinancial Regulation A Transatlantic PerspectiveQuan Pham100% (1)

- Shapers Dragons and Nightmare An OWbN Guide To Clan Tzimisce 2015Document36 pagesShapers Dragons and Nightmare An OWbN Guide To Clan Tzimisce 2015EndelVinicius AlvarezTrindadeNo ratings yet

- Practical Malware AnalysisDocument45 pagesPractical Malware AnalysisHungvv10No ratings yet

- Moore Hunt - Illuminating The Borders. of Northern French and Flemish Manuscripts PDFDocument264 pagesMoore Hunt - Illuminating The Borders. of Northern French and Flemish Manuscripts PDFpablo puche100% (2)

- Wipro Limited-An Overview: Deck Expiry by 05/15/2014Document72 pagesWipro Limited-An Overview: Deck Expiry by 05/15/2014compangelNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument2 pagesCase StudyPragya BiswasNo ratings yet

- SME Finance and Hometown Investment Trust FundsDocument50 pagesSME Finance and Hometown Investment Trust FundsADBI EventsNo ratings yet

- Accounting for Foreign Currency TransactionsDocument32 pagesAccounting for Foreign Currency TransactionsMisganaw DebasNo ratings yet

- Rape Case AppealDocument11 pagesRape Case AppealEricson Sarmiento Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- The Rudimentary Square of Crime: A New Theory of Crime CausationDocument14 pagesThe Rudimentary Square of Crime: A New Theory of Crime Causationgodyson dolfoNo ratings yet

- Humanities Concept PaperDocument6 pagesHumanities Concept PaperGabriel Adora70% (10)

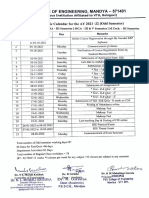

- Tentative Academic Calendar 2021-22 03 Sep 27 2021Document1 pageTentative Academic Calendar 2021-22 03 Sep 27 2021Ral RalteNo ratings yet

- Ann Joo Steel BHD V Pengarah Tanah Dan Galian Negeri Pulau Pinang Anor and Another Appeal (2019) 9 CLJ 153Document24 pagesAnn Joo Steel BHD V Pengarah Tanah Dan Galian Negeri Pulau Pinang Anor and Another Appeal (2019) 9 CLJ 153attyczarNo ratings yet

- Health - Mandate Letter - FINAL - SignedDocument4 pagesHealth - Mandate Letter - FINAL - SignedCTV CalgaryNo ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument18 pagesChapter IHarold Marzan FonacierNo ratings yet

- UK Automotive Composites Supply Chain Study Public Summary 2Document31 pagesUK Automotive Composites Supply Chain Study Public Summary 2pallenNo ratings yet

- Structuralism - AnthropologyDocument3 pagesStructuralism - Anthropologymehrin morshed100% (1)

- My Resume 10Document2 pagesMy Resume 10api-575651430No ratings yet

- Mount ST Mary's CollegeDocument9 pagesMount ST Mary's CollegeIvan GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Case Study - Generative AI Applications in Key IndustriesDocument2 pagesCase Study - Generative AI Applications in Key Industriessujankumar2308No ratings yet

- Supreme Court of the Philippines upholds constitutionality of Act No. 2886Document338 pagesSupreme Court of the Philippines upholds constitutionality of Act No. 2886OlenFuerteNo ratings yet

- Enabling Business of Agriculture - 2016Document262 pagesEnabling Business of Agriculture - 2016Ahmet Rasim DemirtasNo ratings yet

- Bab-1 Philip KotlerDocument11 pagesBab-1 Philip KotlerDyen NataliaNo ratings yet

- ECHR Rules on Time-Barred Paternity Claim in Phinikaridou v CyprusDocument24 pagesECHR Rules on Time-Barred Paternity Claim in Phinikaridou v CyprusGerasimos ManentisNo ratings yet

- FS Pimlico: Information GuideDocument11 pagesFS Pimlico: Information GuideGemma gladeNo ratings yet

- Removal of Corporate PresidentDocument5 pagesRemoval of Corporate PresidentDennisSaycoNo ratings yet

- Trash Essay Emma LindheDocument2 pagesTrash Essay Emma Lindheapi-283879651No ratings yet

- How to exploit insecure direct object references (IDOR) on Vimeo.comDocument4 pagesHow to exploit insecure direct object references (IDOR) on Vimeo.comSohel AhmedNo ratings yet

- A Short Guide To Environmental Protection and Sustainable DevelopmentDocument24 pagesA Short Guide To Environmental Protection and Sustainable DevelopmentSweet tripathiNo ratings yet

- Attitude StrengthDocument3 pagesAttitude StrengthJoanneVivienSardinoBelderolNo ratings yet