Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dargay, 2007 - Vehicle Ownership

Uploaded by

Augusto Dias SiqueiraOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dargay, 2007 - Vehicle Ownership

Uploaded by

Augusto Dias SiqueiraCopyright:

Available Formats

Vehicle Ownership and Income Growth, Worldwide: 1960-2030

Author(s): Joyce Dargay, Dermot Gately and Martin Sommer

Source: The Energy Journal, Vol. 28, No. 4 (2007), pp. 143-170

Published by: International Association for Energy Economics

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41323125 .

Accessed: 15/10/2014 06:41

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

International Association for Energy Economics is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to The Energy Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Vehicle Ownership and Income Growth, Worldwide: 1960-2030

JoyceDargay*,DermotGately** and MartinSommer

***

The speed of vehicleownershipexpansionin emergingmarketand

developing countries has important implicationsfortransport and environmental

policies, as well as the global oil market. The literatureremains dividedon

theissueof whether thevehicleownership rateswillevercatchup to thelevels

commonin theadvancedeconomies.Thispaper contributes to thedebateby

building a model that models

explicitly thevehicle saturationlevel as a function

ofobservable country characteristics: and

urbanization populationdensity. Our

modelis estimatedon thebasis ofpooled time-series (1960-2002) and cross-

sectiondatafor45 countries thatinclude75percentoftheworld'spopulation.We

projectthat thetotal vehicle

stock willincreasefromabout800 millionin2002 to

morethantwobillionunitsin2030. Bythistime , 56% oftheworld'svehicleswill

be ownedbynon-OECD countries , comparedwith24% in 2002. In particular ;

China'svehiclestockwillincreasenearlytwenty-fold , to390 millionin2030. This

fastspeedofvehicleownership expansionimpliesrapidgrowth inoil demand.

1. INTRODUCTION

Economicdevelopment has historically been strongly associatedwith

an increasein thedemandfortransportation and particularlyin thenumberof

roadvehicles.Thisrelationship

is also evidentinthedeveloping economiestoday.

verylittleresearchhas been done on thedeterminants

Surprisingly, of vehicle

ownershipin developingcountries.Typically, analysessuch as IEA (2004) or

OPEC (2004) makeassumptions aboutvehiclesaturation rates- maximum levels

of vehicleownership -

(vehiclesper 1000 people) whichare verymuchlower

thanthevehicleownership alreadyexperienced inmostofthewealthier countries.

TheEnergy Vol.28,No.4.Copyright

Journal, ©2007

bytheIAEE.Allrights

reserved.

* forTransport

Institute Studies, of Leeds,LeedsLS2 9JT,England.

University E-mail:

j.m.dargay@its.leeds.ac.uk.

** Corresponding

author.

Dept.ofEconomics,

NewYork 19W.4 St.,NewYork,

University, NY

10012

USA.E-mail:

Dermot.Gately@NYU.edu.

*** International

Monetary Fund,700 19thSt. NW,Washington,DC 20431USA.E-mail:

Theopinions

MSommer@imf.org. inthispaper

expressed arethose

oftheauthors

andshould

notbeattributed

totheInternational

Monetary itsExecutive

Fund, oritsmanagement.

Board,

143

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

144/TheEnergyJournal

Because ofthisapproach,theirforecasts offuture vehicleownership in currently

developing countries are much lower than would be expectedbycomparison with

developed countries when these were at comparable income levels.

Thispaperempirically estimates thesaturation ratefordifferent countries,

byformalizing the idea thatvehicle saturation levelsmaybe different acrosscoun-

tries.Givendataavailability, we limitourselvesto theinfluence of demographic

factors,urban and A

population populationdensity. higherproportion of urban

and

population greater population density would the

encourage availability anduse

of publictransit, and could reduce the distances traveled by individuals and for

goodstransportation. Thus countries that are more urbanized and denselypopulated

couldhavea lowerneedforvehicles.In thisstudywe attempt to accountforthese

demographic differences byspecifying a country's saturation levelas a function of

itspopulation density andproportion ofthepopulation livinginurbanareas. There

are,ofcourse,a number ofotherreasonswhysaturation mayvaryamongstcoun-

tries.Forexample,theexistence ofreliablepublictransport alternativesandtheuse

ofrailforgoodstransport mayreducethesaturation demandforroadvehicles.Al-

ternatively,investment in a comprehensive roadnetwork willmostlikelyincrease

thesaturation level.Suchfactors, however, aredifficulttotakeintoaccount,as they

wouldrequirefarmoredatathanareavailableforall buta fewcountries.

This paperexaminesthetrendsin thegrowthof thestockof road ve-

hicles(withat leastfourwheels,includingcars,trucks,and buses) fora large

sampleofcountries since1960andmakesprojections ofitsdevelopment through

2030. It employsan S-shapedfunction - theGompertz function - to estimatethe

relationship betweenvehicleownership and per-capitaincome,or GDP. Pooled

time-series and cross-section data are employedto estimateempirically there-

sponsiveness of vehicleownership to incomegrowthat different incomelevels.

By employing a dynamicmodelspecification, whichtakesintoaccountlags in

adjustment ofthevehiclestocktoincomechanges,theinfluence ofincomeon the

vehiclestockovertimeis examined.The estimatesareused,in conjunction with

forecasts ofincomeandpopulation growth, forprojections offuture growth inthe

vehiclestock.

The studybuildson theearlierworkof DargayandGately(1999), who

estimated vehicledemandin a sampleof 26 countries - 20 OECD countries and

six developingcountries- fortheperiod1960 to 1992, and projectedvehicle

ownership ratesuntil2015.

The current studyextendsthatworkin fourways.Firstly, we relaxthe

1999 paper'sassumption of a commonsaturation level forall countries. In our

previousstudy, theestimated saturation level was constrained to be the same for

all countries(at about850 vehiclesperthousandpeople); differences in vehicle

ownership betweencountries at thesameincomelevelwereaccountedforbyal-

lowing saturation to be reached at different incomelevels.

Secondly, the data set is extended in timeto 2002 and adds 19 coun-

tries(mostlynon-OECDcountries) totheoriginal26; these45 countries comprise

aboutthree-fourths ofworldpopulation. The inclusionof a largenumberofnon-

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VehicleOwnership

and IncomeGrowth

, Worldwide:

1960-20301 145

OECD countries - morethanone-third ofthecountries, withthree-fourths ofthe

- a

sample'spopulation provides highdegree of variation in both income and

vehicleownership. Thisallowsmorepreciseestimates oftherelationship between

incomeandvehicleownership at variousstagesofeconomicdevelopment. In ad-

dition,the model is usedfor countries not included in the econometric analysisto

obtainprojections forthe"restoftheworld".

The thirdextensionwe maketo ourearlierstudyconcernstheassump-

tionof symmetry in theresponseof vehicleownership to risingand fallingin-

come.Givenhabitpersistence, thelongevity ofthevehiclestockandexpectations

of risingincome,one mightexpectthatreductions in incomewouldnotlead to

changesin vehicleownership of thesamemagnitude as thoseresulting fromin-

creasingincome.Ifthisis thecase,estimates basedon symmetric modelscan be

misleadingifthereis a significant proportion of observations whereincomede-

clines.Thisis thecase in thecurrent study, particularlyfordeveloping countries.

In mostcountries, realpercapitaincomehas fallenoccasionally, andinArgentina

andSouthAfricaithas fallenovera number ofyears.In orderto accountforpos-

sibleasymmetry, thedemandfunction is specified so thattheadjustment tofalling

incomecan be different fromthatto risingincome.Specifically, themodelper-

mitstheshort-run responseto be different forrisingand fallingincomewithout

changing theequilibrium relationship betweenthevehiclestockandincome.The

hypothesis ofasymmetry is thentestedstatistically.

Finally,thefourth extensionis to use theprojections of vehiclegrowth

to investigatetheimplications forfuture transportation oil demand.Thisis based

on a numberof simplifying assumptions and comparisons are madewithother

projections.

Section2 summarizes thedata used fortheanalysis,and exploresthe

historicalpatterns of vehicleownership and incomegrowth.Section3 presents

theGompertz modelusedin theeconometric estimation, andtheeconometric re-

sultsaredescribedin Section4. Section5 summarizes theprojections forvehicle

ownership, baseduponassumedgrowth ratesofper-capita incomein thevarious

countries. Section6 presents theimplications forthegrowth ofhighwayfuelde-

mand.Section7 presents conclusions. Appendix A describes thedatasources.

2. HISTORICAL PATTERNS IN THE GROWTH OF VEHICLE

OWNERSHIP

Table 1 summarizes data1in 1960 and

thevariouscountries'historical

2002,forper-capita

income(GDP, expressedin 1995 PPP-adjusteddollars),ve-

1.AllOECDcountries

areincluded,

excepting andtheSlovak

Portugal Republic. was

Portugal

excluded

because

wecouldnotgetvehicles

datathat

excluded

2-wheeled andtheSlovak

vehicles,

because

Republic comparabledatawereunavailable

fora sufficiently

longperiod.Amongthe

non-OECDcountries

with data,weexcluded

comparable andHongKongbecause

Singapore their

population wastentimes

density than

greater anyoftheother andweexcluded

countries, Colombia

because

ofimplausible

25%annualreductions

invehicle in1994and1997.

registrations

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

146/TheEnergyJournal

o' ooin - tr>0mr-(N0^rnmr^

oor-t^-unooi/iooaNvoo

^ b

w"o vooN^ot^oooot^iot^oN'O^ovoav^ooNasr-xooovo

g^-£

g s .2

n

e.ts

o ms ^ mm m

in r^«OTtmsot^(Nt^oo^Do40t^m^Dfot^ior^cNO

- -o^oo- ~ 'uo ONh h -< oi

j- g ex.^ m'oommr^oo

ON- ^ _ <N ^ - <Na

o* C - 00-

On .2 C^ooO - - ' OO -

OOOr--OcOi/~> If)'-1- O~

O inr< m

=2 <N- 1

1

A

05

o G^Sy c®

ts <Nso 00 -1000N0sO00Tt<Ns0Omr^>no«nm0Nm^ »OCN

•.S'S. <5

a .S r^r^«o

OOoi 0;i;ooh(NfOtv;oo(NinpoooioM(N^(rj,o^(C

1(N (N -' -< ^ rnrvi-1-'"CN-' oi -' ^

2

£>S

©X)

"es

«

Ifo cq ^o ^00^>0

cs *" ^OO

ei>ei) rn(N^ ^^^^inriairirnriOMiniri^^iriTtorid - -h

<*>C

ju Ja

12^

■go <NONr^

fS

© J>S g ® 00roso

-*

-jmoqrirnoNiori^^q^Nhfnh^Ttini;

^trjTt^o6r^ri(Niod^n--'d^cj|v:rN^:Tt'd

o -=*S ^ - co

(N rt rN mm rn

n• £

0 O «5«- M 1"00 lOO^vOOO^vCi-riMtN^-INO^irihinoirn^

vo vOjSea

S u, irir-o o

OS o ^ 0000^000 SSddddri9odci-o

S3

#© "e3

|~ & ^ ^^DON^

eS VO

eog ** -' -< ^t rTOOO^. OrJN^tN^'- ; t N ^ o -: -. «oinr^

1 fc-ra ©oi>

>• el> uoTtrtio^coONiornrnasoo^-'TtvOTt^^ONcN^

£ X

~|a O -H(N < 10 aOO'0>OO^M'OiO(N'0(NM^'Ch-00^

C •- ©

es

o, ® ^ ^ -00

00 so

'-1 (NrNiioaNoomvooot^^cNOt^r-io^t^fNr^ooN

.& «

s ^Sjs c3 M ON^ M <N ONCNvocNcnso^oooor^oinoooooNinONinooinTt

u o a^

3s*£ vooooor-cN-^miorn'-^'-r^^rtmmoN

S3

£

o

B€ v ^ ^'- ^

[3 g* m .ON jcnONUO- <.-jOOOJOOOOrnm'-.'-jfN-

:

2 B*** £ e§^

ejofefi^"

®® (N<Nt-n' oqr-;Tj;rncn-

^^^^(N^nrilNfN^fN^rifNnri^fNfNfN

©»r>>

* 6

aT o OnON'-; ri^rs;^in0;fn^h'0'-;fno0hfn^^- < SOTJ-

0 vD ^ 00 OJfN^-HM(N-'(N(N(N-1-

(N<^ sb^t^rnrninONTtrocosdoiCNsdmojinodoNinsd

1(N(N(Nrf(N(N CN

s g-B

© Vs

c iL§ - »- Tt-. r-

HH °rSo*£ £ ^NTtaq^oo^io^iofNifnMfNcj^^qtNri

c *~^o^

£

2 t-H m Mooinooo^d^^ooONTtTt'ioooKd^^Ttdoi

o _ ^ ^

o

GQ

IS 2«~ oso o m

Q x>t. on r-

2 2

"3 tS e g

'u

o 2 I (3 D I I S U 3 I Q I" E S, o o ! £ 2 « J I I £ I t2

s - I

"S2_-§ -S

" g? w

5«r5CD- = -2

- « ^ n - eIK « ^ i 2«>, e

tO-oTag a .5 a « r J

3 1 a 1 .a I gS3>.alEi-i^|sSg,sJiilgs|^

£ 5 OUDS 0<MwU0QME£00I^^^JZZi£t«f2

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and IncomeGrowth

VehicleOwnership 1960-2030/ 147

, Worldwide:

-OnON oo 00 tJ- COon

CNm>o

CN00 OO-Hm

Tt00 in00 Hh

t--CO

ooNO ooCNoo(-*-

ooNOno*0 in rooo eno

N 90

(NinTj- Tfrrr->rrrf

coon

tj-co -in -hm

ff)(N

-h « oovo nooo no<nr- r--< coTfoo x Xt X

ro oo

rt h

^ ^ ^^ noonco mo^<nr-oo<N

r--- 1co -i -< 'o N f')vi

or-ooTt

(NfN^t co^r~-

oo onm

<-<-1 - •

ocndo

no cor-

^ in

tj- in

oo co inin

o) no^ N xj-yo rf i r*.

n©i-

On r-*

<N© ro

-< --I CNlO

(N ,-H - H ^V)N

H rH

^ X

m

OnCN 00OCOn noOn Tt^ h -in< ONCOCNt"-- OON

r~-On »«N © iH

ON Ttin

-; O o NO

(NTf-

-^ Tj-h; ^"Hf 1ooON

^(NTt 1o' > IO ffj

hm

O <N (N so- 3^cocn; <N^ <N-« h « H ri H

^h Tt

^ ^h (N

^ ^ oo^ ^ h^ ^ ^ o

^ en ^ ^ ^ ^o ^ ^NO-^ ^NO^ ^o ^ ^ ^ ^

rnon>nr! ^irlS in

S OO ^ ooo! ^ ^S Is;

T); ^ ^ oo^ ; OnS h ^ ^ H ^ ^

n m' tt r-^tt tt

inWON't -; OO(NO inON00« ON inOn(NTJ-

ONh Wh V)N

-1 (N-1 : O ^ ^ Xr*003

- noco

<n - 1cn CN(N o

o CN^ NOs iri oc £J

O ^ 2 w

So

oocnno onO o m nn^ (N<N(NTt<N-; -^ X rfmOn(S

(N-^ P

o d o^oPP 00 o o o P

o 0000000 i 22

'-; noONO -; NOi; en(N o (S (S -; -; 00inTt00h h h x (S H ^ x

(N 00rl oi co rtinS in 'o nori oi ononnono 00 <s*i/>fi i/$c4

(Non mm'-i no-< 00

-. o 00

cocoonincn no cn-r»

noon

*-'o 1o cn

- r- n©tir>© On©

co inon

NOon M NO _h(NtJ-

x m cn10co*-

o ini (N CN -cn

tj- « nc

i-H i/i

I/)w w

i-*

noOn • ^r- in

-- cn o r- cnr-1 no 00

- r-ON Ttmr-NONO ^ - o^ cn

coTf inh ro

»nv»© t H

no

CN CN in(N <-5 ^01

^ 1-1 rt

irj

^- ^- ^00Tt

^ ^m ^in(N

^ ^ ^O ^ (N

00^ cn

^ Tt

^ ^h ^ino

^ co

^ co

^ 00 ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^

^ ^00Tf

cn; -*t

; in-< P cnTfcn^ cn »-h*

cnO noincocnco-^ -<tco oott co©

ri © r4cj ci

o ON^ NO NO^ CNO ON IT)ONNO-H00 cninONrn^ OO (N S© fN| >o©

M in

incn

CN -1oi

^ Onr-^onnocn rnH

^ rnw oo oocncnoo-^ no oo(*5^CNW^

rt-<

N

Ttinrt«^ h h oocnh cnrn- cn rnoo h on(N

; r-; O coO O cnOonO

O ^

<-i Tf *-* Oncn^ cn^ ai-^cncN^HNO

63 ri ^X ^h f*i

^fi 1 1

w

Jm

u CN

eBNOCNCNCN

NONONOON NOi-h

NO^2 CONOCN

NO CNNO CN

NOrf

r- r-

NO

'£2^222 ^ ONONON ON ONON ON

H&i lusli Si^li-a .elisls^ I 1

a ! * I < -c HaS

'£ «. go' t§ tf S eS | £| S g ?

5 u « o £<->£« U "S -.^SoQOo

5 Sg.s •- S g S <g

Q^eCdN

i O c -3 .. .S T3

03 Oi *-»

ft , P - O 53<Sc -Ble»<Wuife

^ ^ "rv^ H O -M

u ^ U s. J,<U'n C U 2 2 'S iCCnS^3-^--* fl 22O !7

§1^1 Z II 5 Q I IdSSiHII ll I

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

148/TheEnergyJournal

Figure 1. VehicleOwnershipand Per-CapitaIncomeforUSA, Germany,

Japan,and South Korea, withan IllustrativeGompertzFunction,

1960-2002

Figure2. VehicleOwnershipand Per-capitaIncomeforSouth Korea,

Brazil, China, and India, withtheSame IllustrativeGompertz

Function,1960-2002

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VehicleOwnership

and IncomeGrowth

, Worldwide:

1960-2030/ 149

hide ownership (per 1000 people),and population.Comparisons of thedatafor

1960and2002 aregraphedbelow(in Section5, we presentsimilargraphiccom-

parisonsbetween2002 andtheprojections for2030).

Therelationship betweenthegrowth ofvehicleownership andper-capita

incomeis highlynon-linear. Vehicleownership growsrelatively slowlyatthelow-

estlevelsof per-capita

income, then about twice as fastas income at middle-in-

comelevels(from$3,000to $10,000percapita),and finally, aboutas fastas in-

comeathigherincomelevels,beforereaching itsmaximum level("saturation")at

thehighestlevelsofincome.Thisrelationship is shownin Figure1,usingannual

dataovertheentireperiod1960-2002fortheUSA, Germany, Japanand South

Korea;in the background is an illustrative

Gompertz function that is on average

of oureconometric

representative resultsbelow.Figure2 showssimilardatafor

China,India,Brazil and SouthKorea- withthesame Gompertzfunction, but

usinglogarithmic scales. Figure3 showstheillustrative Gompertzrelationship

betweenvehicleownership andper-capita income,as wellas theincomeelasticity

ofvehicleownership at different levelsofper-capita income.

3. THE MODEL

As illustrated

above,we represent

therelationship betweenvehicleown-

ershipandper-capita incomebyan S-shapedcurve.Thisimpliesthatvehicleown-

ershipincreasesslowlyat thelowestincomelevels,and thenmorerapidlyas in-

comerises,andfinally slowsdownas saturation is approached.

Therearea number

of different

functional formsthatcan describesucha process - forexample,the

logarithmic

logistic, cumulative

logistic, normal, andGompertz functions.

Follow-

ingourearlierstudies,theGompertz modelwas chosenfortheempirical analysis,

becauseitis relatively

easytoestimateandis moreflexible thanthelogisticmodel,

byallowingdifferent

particularly curvatures

at low-andhigh-income levels.2

LettingV* denotethelong-run equilibrium levelof vehicleownership

(vehiclesper1000people),andletting GDP denoteper-capita income(expressed

inreal 1995dollarsevaluatedat PurchasingPowerParities),theGompertz model

can be written as:

'

r = (i)

whereyis thesaturation

level(measuredinvehiclesper1000people)anda andp

arenegativeparametersdefining ofthefunction.

theshape,orcurvature,

The impliedlong-run of thevehicle/population

elasticity ratiowithre-

specttoper-capita

incomeis notconstant,

duetothenatureofthefunctional form,

butinsteadvarieswithincome.The long-run is calculatedas:

incomeelasticity

2.SeeDargay-Gately

(1999)for

a simpler

model, a smaller

using setofcountries.

Earlier

analyses

aresummarized

inMogridge which

(1983), discusses

vehicle

ownership modelled

being byvarious

functions

S-shaped oftime,

rather

thanofper-capita

income,some

with saturation

andsomewithout.

MedlockandSoligo a log-quadratic

(2002)employ ofper-capita

function income.

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

150/TheEnergyJournal

$GDPt

'

y^R= ccpGDPte (2)

Thiselasticityis positiveforall incomelevels,becausea andP arenega-

tive.The elasticityincreasesfromzero at GDP=0 to a maximumat GDP=-l/p,

thendeclinesto zero asymptotically as saturation is approached.Thus P deter-

minestheper-capita incomelevelat whichvehicleownership becomessaturated:

thelargerthep in absolutevalue,thelowertheincomelevel at whichvehicle

ownership flattensout.Figure3 depictsan illustrative Gompertz similar

function,

to whatwe have estimatedeconometrically, together withthe impliedincome

forall incomelevels3.

elasticity

ShowninFigure4 arethehistorical ratiosofvehicleownership growth to

per-capitaincomegrowth(whichapproximates theincomeelasticity),compared

tothecountries' averagelevelofper-capita income(forthelargestcountries, with

populationabove 20 millionin 2002). Also graphedis theincomeelasticityof

vehicleownership forourillustrativeGompertz function. One canobservethepat-

ternacrosscountries oftheincomeelasticity increasing atthelowestlevelsofper-

capitaincome,thenpeakingintheper-capita incomerangeof$5,000to $10,000,

followedbya gradualdeclinein theincomeelasticity at higherincomelevels.

We assumethattheGompertzfunction (1) describesthelong-run rela-

tionshipbetweenvehicleownership andper-capita income.In ordertoaccountfor

lags intheadjustment ofvehicleownership to per-capita income,a simplepartial

adjustment mechanism is postulated:

y= o)

whereV is actualvehicleownership and 0 is thespeedof adjustment (0 < 0 <1).

Such lags reflect

theslow adjustment of vehicleownership to increasedincome:

thenecessarybuild-upof savingsto affordownership;thegradualchangesin

housingpatterns and landuse thatare associatedwithincreasedownership; and

theslowdemographic as

changes young adultslearn to drive,replacing their el-

derswhohaveneverdriven.Substituting equation (1) intoequation (3), we have

theequation:

°*PGDPt

+ (1 - 0)V ,

Vt= yde (4)

In DargayandGately(1999), we had assumedthatonlythecoefficients

p. were whileall theotherparameters

country-specific, oftheGompertz function

werethesame forall countries:thesaturation level y,thespeed of adjustment

0, and thecoefficienta. Thus,differences betweencountriesin thatpaperwere

reflected in thecurvatureparameters p. , whichdetermined theincomelevelfor

3. Asdiscussed there

below, canbe differences

across

countries

inthesaturation

levelsofa

country's function

Gompertz anditsincome

elasticity. 3 plots

Figure anillustrative

functionforthe

median saturation

country's level.

Differences

across

countries inFigure

areillustrated 6.

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VehicleOwnership

and IncomeGrowth

, Worldwide

: 1960-2030/ 151

Figure3. IllustrativeGompertzFunctionand itsImpliedIncomeElasticity

Figure4. HistoricalRatios ofVehicleOwnershipGrowthto Income

Growth,byLevels ofPer-capitaIncome: 1960-2002

each country at whichthecommonlevelof saturation is reached(620 cars and

850 vehiclesper1000people).In thispaperwe relaxthisrestriction ofa common

saturation

level.Instead,we assumethatthemaximumsaturation level will be

thatestimated fortheUSA, denotedyMAX. Othercountries thataremoreurbanized

and moredenselypopulatedthantheUSA willhavelowersaturation levels.The

saturation

levelforcountry i at timet is specifiedas:4

4. Population andurbanization

density arenormalised thedeviations

bytaking fromtheir

means

overallcountries

andyearsinthedatasample.

Sincepopulation andurbanization

density varyover

sotoodoesthesaturation

time, level.

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

152/TheEnergyJournal

y„=yMAx+XD„+vv„

where

D it=D it-D„„, if D it>Dn„.

USA,t USA.t

= 0 otherwise (5)

and

U.=U.~

it it U.„A , if £/,

USA.t it> U„,A

,

USA.t

= 0 otherwise

whereX and cpare negative,and D.tdenotespopulationdensityand Ujtdenotes

in country

urbanization i at timet.

Figure5. Countries'PopulationDensityand Urbanization,2002

1000

1

Twn

Kor

Ind Jpn

Pak Ita Deu

100 ^ ChTdn Pt' f"

Population Eav Esp

9y JJysTur

Density Zaf USA

2002

(persq. KM, Bra

logscale)

Can

Aus

1 1 1 1 1

0 20 40 60 80 100

2002

% Urbanized,

Figure5 plotsthe2002 dataon populationdensityandurbanization, for

countries withpopulationgreaterthan 20 million.

The most urbanizedand dense-

lypopulatedcountries areinWestern EuropeandEastAsia: Germany, GreatBrit-

ain,JapanandSouthKorea.Some countries arehighlyurbanizedbutnotdensely

populated,suchas Australiaand Canada. Othersare denselypopulatedbutnot

highlyurbanized, suchas China,India,Pakistan, Thailand,andIndonesia.

The dynamicspecification in equations(3) and (4) assumesthatthere-

sponseto a fallin incomeis equal butoppositetheresponseto an equivalentrise

in income.As mentioned earlier,thereis evidencethatthismaynotbe thecase,

andthatassumingsymmetry maylead to biasedestimatesof incomeelasticities.

Many of thecountriesinthesamplehaveexperienced periodsofnegativechanges

inper-capita income,someforseveralyears,suchas Argentina andSouthAfrica.

Thus it is importantthatwe takesuchasymmetry intoconsideration. To do so,

theadjustment coefficient

relating to periodsoffallingincome,0F , is allowedto

be differentfromthatto risingincome,0^. This is doneby creatingtwodummy

variablesdefinedas:

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and IncomeGrowth

VehicleOwnership 1960-2030/ 153

, Worldwide:

Rit= 1 ifGDP It- GDPIt-.1> 0 and = 0 otherwise

((L'

K '

Fit= 1 ifGDPit- GDP it-

.1< 0 and = 0 otherwise

andreplacing0 in (4) with:

e= + (7)

Thisspecificationdoes notchangetheequilibrium relationshipbetween

thevehiclestockandincomegiveninequation(1), northelong-run incomeelas-

ticities.Onlytherateofadjustment to equilibriumis differentforrisingandfall-

ingincome,so that the short-run and

elasticities thetime requiredforadjustment

will be different.Since it is likelythatvehicleownershipdoes notdeclineas

quicklywhenincomefallsas itincreaseswhenincomerises,we expect0^ > 0F.

The hypothesis of asymmetry can be testedstatisticallyfromtheestimates of 0^

and0F Iftheyarenotstatistically differentfromeach other,symmetry cannotbe

rejectedandthemodelreverts tothetraditional, symmetric case.

Substituting(5) and (7) into(4), themodelto be estimated econometri-

callyfromthepooleddatasamplebecomes:

- - pGDP.f

n = (Y^+ XD, (pt/„)(0A + 0A)^'

+ W

+ ('-QRRi-QFFJVii_l+ eii

wherethesubscript i representscountry i and £itis therandomerrorterm.The

adjustment parameters,0^ and 0F , and theparameters 9 and X arecon-

a, yMAr

strained tobe thesameforall countries,while(3.is allowedtobe country-specific,

as is eachcountry'ssaturationlevelfromequation(5). The long-run incomeelas-

ticitiesforeachcountry arecalculatedas

p.GDP.

Tif = aP .GDP.tel (9)

whicharethesameas inthesymmetric incomeelastici-

model(2). The short-run

tiesarealso determined

bytheadjustment

parameter,0, andare

p.GDP.,

Tlf = 0(XpGDP.e . (10)

where0 = 0D a forincomeincreasesand0 = 0rr forincomedecreases.

dataacrosscountries

The rationaleforpoolingtime-series is thefollow-

to estimatea separatevehicleownership

ing.Althoughit is possible,in theory,

function foreach country, theshorttimeperiodsand relatively smallrangeof

incomelevelsthatare availableforeach country makesuchan approachunten-

able. Reliableestimation levelrequiresobservations

of thesaturation on vehicle

ownership whicharenearingsaturation.

Analogously, estimationoftheparameter

a, whichdetermines thevalue of theGompertzfunction at thelowestincome

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

154 /TheEnergyJournal

levels,necessitatesobservations forlow incomeand ownershiplevels.Thus it

wouldnotbe sensibleto estimatethesaturation level forlow-incomecountries

separately, in

because vehicleownership thesecountriesis farfromsaturation.

Similarly,one couldnotestimatethelowerendofthecurve,i.e. theparameter a,

on thebasisofdataonlyforhigh-income countries withhighvehicle-ownership,

unlesshistoricdatawereavailableformanyyearsin thepast.Forthesereasons,

we use a pooledtime-seriescross-sectionapproach,withall countries beingmod-

eled simultaneously.

We hadconsidered additional

utilizing explanatory variablesinthemod-

el, suchas thecostof vehicleownership, or thepriceof gasoline.5However,the

unavailabilityof data fora sufficientnumberof countriesand yearsprevented

suchan attempt.

4. MODEL ESTIMATION

The modeldescribedinequation(8) was estimated forthepooledcross-

sectiontime-series dataon vehicleownership forthe45 countries. The periodof

estimation is generallyfrom1960 to 2002, butis shorter forsomecountries due

to earlydatabeingunavailable(see Table 1). In all, we have 1838 observations.

In orderto allow largercountries to havemoreinfluence on theestimated coef-

ficients,theobservations wereweightedwithpopulation.As mentioned above,

themaximumsaturation level,yMAX,thespeed-of-adjustment coefficients,0^ and

0F, and the lower-curvature parameter a were constrained to be the same forall

countries.The upper-curvature parameters (3.were estimated separately each

for

country. The model was estimated using iterative leastsquares.

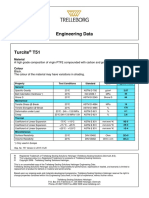

The resultingestimatesare shownin Table 2. A totalof 51 parameters

areestimated, including45 country-specific p..All theestimated coefficientsare

oftheexpectedsigns:0^ , 0F, andyMAX arepositiveanda, X,cpandp. arenegative.

All coefficientsarestatistically

significant,exceptforthep. coefficients forLux-

embourg, Iceland, Ecuador, and Syria. From the Adjusted R2, we see the model

explains the dataverywell;however, thisis to be expected in a model containing

a laggeddependent variable.Fouralternative specificationswerealso estimated,

withsimilareconometric results6.

5.Storchmann (2005)usesfuel thefixed

price, costofvehicle

ownership,andincome distribution

- butnotper-capita

income - toexplainvehicle

ownershipacross

countries.

Hisdatasetincludes

more

countries

(90)butonly a shorttime 1990-1997.

series, Medlock andSoligo(2002),witha smaller

set

ofcountries,utilize

theprice ofhighway fueltomodel thecross-country

fixedeffects

within

a log-

quadratic

approximation ofvehicle ownership.

6.Thealternativespecificationswere:

(1)ReferenceCasebutwithout using Density;

Population

(2) ReferenceCasebutwithout using (3) Reference

Urbanization; Casebutwithout allowingfor

Asymmetric Income Responsiveness;(4) Common Levels:

Saturation Dargay-Gately(1999)with

Symmetric Income Response. Theeconometric results

were similar

across Allthe

allspecifications.

coefficients

havetheexpected signandarestatistically

significant

(except p.for

forcountry-specific

some smaller asinTable2.Detailed

countries), results

areavailable

upon requestfromtheauthors.

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VehicleOwnership

and IncomeGrowth,

Worldwide:

1960-2030/ 155

The estimated adjustment parameter is largerforrisingincomethanfor

fallingincome, 0.095 versus 0.084. Testing equality0^ = 0Fyieldsan F-statis-

the

ticof4.76 (withprobability value=0.03)so thatsymmetry is rejected.Thisimplies

thatthevehiclestockrespondsless quicklywhenincomefallsthanwhenincome

rises.Withincreasingincome,9.5% of thecompleteadjustment occursin one

year, butwhen income fallsonly 8.4% of thelong-term adjustment occursin one

year.Thus a fallin per-capita income reduces vehicle ownership about 11% lessin

theshortrun(1-year)thanan equivalentrisein incomeincreasesvehicleowner-

ship.The long-run elasticityis thesameforbothincomeincreasesanddecreases.

The vehiclesaturation levelsvaryacrosscountries - froma minimum

of508 forChineseTaipeito a maximum of852 fortheUSA (andforthosecoun-

trieswhichare less urbanizedand less denselypopulated:Finland,Norway,and

SouthAfrica).All theOECD countries havesaturation levelsabove700 exceptfor

themosturbanized anddenselypopulated:Netherlands (613), Belgium(647), and

SouthKorea(646). Similarly, mostof theNon-OECD countries havesaturation

levelsin therangeof 700 to 800 vehiclesper 1000 people.The coefficients for

population density andurbanization arebothnegativeandstatistically significant,

indicatingthatthesaturation leveldeclineswithincreasing population densityand

withincreasing urbanization. The lowestsaturation levelsamongthelargestcoun-

triesareforGermany, GreatBritain, Japan,SouthKoreaandIndia7.Figure6 plots

foreach country (withpopulationgreater than20 millionin 2002) theestimated

saturationleveland theincomelevelat whichit wouldreachvehicleownership

of200 vehiclesper1000people.The lattermeasuresreflects thecountry's curva-

tureparameter p.. Some countries wouldreachvehicleownership of200 quickly,

at relatively

low incomelevels(USA, India,Indonesia,Malaysia),whileothers

wouldreachitmoreslowly,at muchhigherincomelevels(China,France).

Thevalueofa determines themaximum incomeelasticity ofvehicleown-

ership which

rates8, in thiscase is estimated to be 2. 1. The value of p. determines

theincomelevelwherethecommonmaximumelasticity is reached:thesmaller

7. InMedlock-Soligo (2002),there ismuch wider invehicle-ownership

variation

cross-country

saturationlevels

estimated - nearly from

tenfold, lowest tohighest

(China) (USA).Their estimated

ownership-saturationlevels

(forpassenger vehiclesonly) rangefrom600intheUSAandItaly, 400-

500inthemost oftheOECD,150-200 inMexico, Turkey,SouthKoreaandmost ofNon-OECD

Asia,butlessthan 100forChina. Thislarge isduetothefact

variability that

saturationlevelsinthe

Medlock-Soligo model areclosely related

totheestimated fixed - therefore,

effects thecalculated

saturation donottakeintoaccount

levels as much as inourframework.

information

cross-country

Forcomparison, ourestimated ownership-saturationlevels arealmost

estimates allwithin10%ofthe

average saturation

level.Onlythose countries

thataremost urbanized

anddensely populated have

estimatedsaturationlevelsthataresubstantiallylower; thelowest

saturation

level(Twn) is 60%of

thehighest (USA).Attheother extreme, therewasnocross-country invehicle

variation ownership

saturation inDargay-Gately

levels (1999),which assumed a shared

saturation

levelacross countries

that

wasestimated tobe850vehicles (652cars)per1000people.

8. Themaximum is derived

elasticity bysetting thederivative

ofthelong-run with

elasticity

respecttoGDPequaltozero, solving forthevalueofGDPwhere theelasticity

isa maximum and

replacingthisvalueofGDP(=-l/p) intheoriginal formula.

elasticity Thisgives

a maximum elasticity

of-ae1= -0.367a.

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

156 /TheEnergyJournal

Figure6. Countries'EstimatedVehicleOwnershipSaturationLevels and

IncomeLevels at whichVehicleOwnership= 200

900

USAMox Zaf

Mar.Mys

Mar

Pol.-EayI. BraCan

Tuf'P Fra

800 Ita ChnArg

idn Aus

vehicle

ownership

saturation PakJpn

p-*Br

level 700 lnd

(vehicles

per1000 Kor

people)600

Twn

500 1 1 1 ^

4 6 8 10 12

income

per-capita 1995

(thousands $ PPP)

atwhich

vehicle =200inlong

ownership run

thep. in absolutevalue,thegreater theper-capita incomeat whichthemaximum

incomeelasticity occurs- forthedifferent countriesrespectively, at incomelevels

between$4,000and $9,600.The vehicleownership levelat whichthemaximum

income-elasticity occursis about90 vehiclesper 1000 people.The valuesof a

andp. also determine theincomelevelat whichvehiclesaturation is reached.The

estimatesimplythat99% of saturation is reached,forthedifferent countries re-

spectively,at a per-capita

incomelevelofbetween$19,000and$46,000.

The graphsin Figure7 illustrate thecross-country differences in satura-

tionlevelsand low-incomecurvature forsix selectedcountries.Countriescan

differin theirsaturation level,or theirlow-incomecurvature (measuredby the

incomelevelat whichvehicleownership of 200 is reached),or both.USA and

Francehave similarsaturation levelsbutdifferent low-incomecurvatures: USA

reaches200 vehicleownership atper-capita incomeof$7,000whileFrancereach-

es itat $9,400.Such differences couldbe theresultof differences in thecostof

and

owning operating or

vehicles, other variablesfor which we do not havedata.

Franceand Netherlands reach200 vehicleownershipat similarincomelevels,

butFrancehas a muchhighersaturation level(823) thandoes Netherlands (613).

Similarly,India and Indonesiahave similar low-income curvatures - reachingve-

hicleownership of200 atabout$6,500- butIndia'ssaturation level(683) is lower

thanIndonesia's(808) becauseIndiais moreurbanizedandhashigherpopulation

density.By contrast, China reachesvehicleownershipof 200 moreslowly(at

about$10,000)thanIndiabutithas a highersaturation level.9

9.AlthoughChina ismore urbanized

than ithasmuch

India, lower aswehave

density

population

measuredit,usinglandarea.Sincemuch ofwestern

Chinaisvirtually itwould

uninhabitable, have

beenpreferabletousehabitablelandarearather

than totallandareawhencalculating

population

butsuchdataareunavailable.

density, Thiswould havetheeffectoflowering

China'sestimated

saturation

leveltosomethingclosertothat

ofIndia ofthis

(683).Theeffect onChina's is

projections

discussed

inthenext section.

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VehicleOwnership

and IncomeGrowth,

Worldwide:

1960-2030/ 157

Table 2. EstimatedCoefficients ofEquation (8)

coef. P-value

Speedofadjustment0

income increases 0.095 0.0000

income decreases 0.084 0.0000

max.saturationlevel 852 0.0000

population X

density -0.0003880.0000

urbanization

<j) -0.0077650.0001

alphaa -5.897 0.0000

vehicle income

per-capita

1995$ PPP)

ownership(thousands

saturation atwhichvehicle

Country = 200

betacoef. P-value (per1000people) ownership

OECD,North America

Canada -0.15 0.00 845 9.4

UnitedStates -0.20 0.00 852 7.0

Mexico -0.17 0.00 840 7.9

OECD,Europe

Austria -0.15 0.00 831 9.4

Belgium -0.20 0.00 647 8.1

Switzerland -0.11 0.00 803 13.3

CzechRepublic -0.17 0.00 819 8.3

Germany -0.18 0.00 728 8.5

Denmark -0.12 0.00 782 12.0

Spain -0.17 0.00 835 8.1

Finland -0.13 0.00 852 10.6

France -0.15 0.00 823 9.4

GreatBritain -0.17 0.00 707 8.9

Greece -0.15 0.00 836 9.4

Hungary -0.17 0.00 831 8.1

Ireland -0.15 0.01 841 9.4

Iceland -0.17 0.87 779 8.3

Italy -0.18 0.00 800 8.1

Luxembourg -0.16 0.78 706 9.6

Netherlands -0.16 0.00 613 10.1

Norway -0.13 0.00 852 10.6

Poland -0.23 0.00 821 6.2

Sweden -0.13 0.00 825 10.6

Turkey -0.18 0.00 820 7.7

OECD,Pacific

Australia -0.19 0.00 785 7.7

Japan -0.18 0.00 732 8.3

Korea -0.20 0.00 646 8.1

NewZealand -0.19 0.01 812 7.3

Non-OECD, South

America

Argentina -0.13 0.00 800 10.6

Brazil -0.17 0.00 831 8.5

Chile -0.17 0.00 810 8.3

DominicanRep. -0.24 0.02 111 6.2

Ecuador -0.25 0.13 845 5.6

continued

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

158/TheEnergyJournal

Table 2. EstimatedCoefficientsofEquation (8) (continued)

vehicle income

per-capita

ownership(thousands1995$ PPP)

saturation atwhich vehicle

Country betacoef. P-value (per1000people) ownership = 200

Non-OECD, Africa

andMiddle East

Egypt -0.22 0.00 824 6.3

Israel -0.13 0.00 630 12.6

Morocco -0.25 0.00 830 5.6

Syria -0.22 0.22 807 6.5

SouthAfrica -0.14 0.00 852 10.1

Non-OECD, Asia

China -0.14 0.00 807 10.1

ChineseTaipei -0.16 0.00 508 11.7

Indonesia -0.23 0.00 808 6.3

India -0.24 0.00 683 6.5

Malaysia -0.23 0.00 827 6.0

Pakistan -0.21 0.01 725 7.3

Thailand -0.22 0.00 812 6.3

R-squared 0.999821

Adjusted

SumofSquaredResiduals

0.038947

Figure7. Long-runGompertzFunctionsforSix SelectedCountries,and

theImpliedIncomeElasticityofVehicleOwnership

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and IncomeGrowth

VehicleOwnership 1960-2030/ 159

, Worldwide:

5. PROJECTIONS OF VEHICLE OWNERSHIP TO 2030

On thebasisofassumptions concerning future trendsinincome,popula-

tionand urbanization, the model projects vehicle ownership foreach country.10

TheseareshowninTable3.

WithintheOECD countries, projectedgrowthin vehicleownership is

slow,about0.6% annually,

relatively because many of these countries are ap-

proachingsaturation. The onlyexceptionsto slowlygrowingvehicleownership

in theOECD areMexico andTurkey, whosevehicleownership willgrowfaster

thanincome.However,due to populationgrowth, theannual OECD growth rate

fortotalvehiclesis somewhathigher,at 1.4%. For theUSA, we projectonlya

slightincreaseinvehicleownership (from812 to 849 per1000people)buta large

absoluteincreaseinthetotalvehiclestockof80 million,duetopopulation growth

of nearly1% annually.This 80 millionincreasefortheUSA is largerthanthe

projected2030 totalofvehiclesinanyEuropeancountry, andis almostas largeas

thetotalnumber ofvehiclesinJapan.

Forthenon-OECDcountries11, we projectmuchfasterratesof growth:

vehicleownership growthof about3.5% annually, and totalvehiclesgrowthof

6.5% annually - fourtimestheratefortheOECD. The mostrapidgrowth is inthe

non-OECDeconomieswithhighratesof incomegrowth, and per-capitaincome

levels($3,000to $10,000)at whichtheincomeelasticity of vehicleownership is

thehighest.Chinahas byfarthehighestgrowth rateofvehicleownership, 10.6%

annually,followedbyIndia(7%) andIndonesia(6.5%). By 2030,Chinawillhave

269 vehiclesper 1000people- comparableto vehicleownership levelsofJapan

andWestern Europe in theearly 1970's - and it will have more vehiclesthanany

othercountry: 24% morevehiclesthantheUSA. China's vehicleownership is

to

projected growrapidly for two reasons: (1) itsprojected high growth rate for

per-capitaincomeduring2002-2030,4.8% (whichis actuallymuchslowerthan

itsrecentrapidgrowth, and lowerthanthe5.6% growth ratefor2003-2030that

is assumedinDOE's International Energy Outlook 2006), and(2) vehicleowner-

shipgrowing 2.2 times as fastas per-capita income, as itpassesthrough themiddle

levelofper-capita income($3,000to $10,000)withthehighestincome-elasticity

ofvehicleownership. Similarly forIndiaandIndonesia,whoseper-capita income

10.Population is assumed

density togrowat thesamerateas population. for

Projections

areobtained

urbanization byestimatinga modelrelating toper-capita

urbanization income andlagged

urbanization over

forallcountries thesampleperiod forecasts

andcreating onthebasisofthismodel

andtheprojected income

per-capita Themodel

values. usedandtheestimates areavailable

obtained

uponrequest.

11. Forthe"Other"(non-sample)countries weprojected

oftheworld,

intherest vehicle

ownership

fromourestimated Gompertzfunction's tothis"Other"

adapted

parameters, characteristics.

group's

In2002this group income

hadper-capita ofabout$3000andowned 44vehicles per1000people.We

estimatedthegroup'scoefficient thesample

byregressing (3.values

countries' against of

thelevels

income

per-capita atwhich

therespective per1000people;

had44vehicles

countries thisproduceda

valueofp.=-0.21 for"Other"countries.

Using thesample median

countries' value(812),

saturation

weassumed 1.7%annual income

per-capita growthfor"Other"

countries,andprojected vehicle

their

ownership to2030.

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

160/TheEnergyJournal

"o3

if « ^vo^on^O - - .rn<NO - - 0<Ncn - >or-;»nTt- <Nc^<Np<N

mom ^ -

^ bi>©3o do - 000000000000000^0000

.1 ^

JL o r-

mo r* 00-- r--o<N»oo>oiori- in- r^

- 00 Tt vovo-- on10o n - 10m onci

ON

e

.0

2

M m^-

3i

"3

o.

(X o 00- ooot^-omm

- - ON-xOTtor^ovomONONr-

- 00 ^- •n vom- - *0 - m no

o mooO

fN-

in .

~ B, ^ o>

.2JS®5J©

«•"t A ac- NOO <N rnrn^irifOOO^^in^hhONfNfNq^OO'O^^ -

o 00- 00000000000000000000

2 ^

OX)

73

if. ^00^- ^0 0000h - vooNtNoommoor^r^ocN - o ONcn <N

«5«

oi^ -*- m ooooio - - - - - - oi<N-'d*- - - <Nvq

- vo

_a> J?

C

"3^

le g o o^t^o Tfr-os- inONr^cNmor-^tONmfSTteNO"*tpr-;

>^ :=

r= 2 ^ o^»n ^^'thVrn-;Tt'd^rv'^^6gdd^^>^

mr^ioTj- ,-f. 01 co

i~ c* (NTt>

00£3no -inqOrfifriaN^rn^^OO'Nhrih;'t,t^,t

iriinrtTtoociricN'nd^^^

§ Ttramrn d^d^ri^t^NO

^ -1

©

o

«?

n if

eso 2^*" <NtNO - -

o

o . co djd - o ^ ONr^pmr^oqtNr-; - (Nf^rsiodod1 oovqinvqo

od^tNO-H-x - - pofNpin^q - (N- >o

> dId

a, £.1

s| eL |®

2cn•- 235;

0000 S^§S2S5?SS^S»§SiS^P

xvc^i^r^t^t^r^r^vot^r^soi 1^ h ^ x 1 m

u ■§®

u - OO^D

C y-Z £J 2 -00CM

*-<ir> ONOONONOO^OONO»0«NsO<N<NvOsor-

ntNinoNoor,vcooh-tNorr^^^^^o^

* NO

o

2 "3

£ £§5 fcilg

w

^vnsip djd O - rn

- n(N^o^-iornqn^^-:(Nw^ooo)^nq - - Tf<NCO

c Sv)^ (N

Cxi N(NfSTt^'oifS(N(Noi(Si:NN(N--

OJf«wT§ ®

E ® (NNDcn 00n m M - r^o - <N- ooo«o«ooocnv>r-;- . -

©

o •|| £2

C ||

HH •ti o ONON - cor^r^NOmoNrnr^r^Nq - cnoor-.ro^Dfn-NO^t-

2 -

© (Nfl 00

so ^^^HffiinONTffnfn^oiON^ritN^oooNiAivo

^r!|(N-H(N(N-r)(N(N--(N(N(NTt(N(N <N

c CO

#©

"<C #W

'u

<u

8 E

o9

u < 0) y

Pu j3 CA Q«

O o c

fe £ fa -o 3 *5 tin

^ <3

Z 3 w Jls-iS - =-

M Is, B

- £>q-S-oR 0".« 3 6 7 5 ; 1= « S « ^ "i E 15 ^ 13 5

3 ik oil* Ss-as-Sll-llcsSc^l^laES-Sl

£ <3 OUDS 0<fflwUDQwfc£00J:i^«JZZDHWh

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VehicleOwnership

and IncomeGrowth

, Worldwide:

1960-20301 161

h (N(N^ o' o Ono a -1m cooom

r^ ^oooN^mmvo ^ ^ Ho

dodo dod^'d o o o d -< -1cno K

© © *h*h

rt-; o ON(s

<NO ^- I r- ONONCO(N

On<N ^ ONOOh ifl

<n<n>o

-1 <n(N

^ o

^ ^ m

^ <ncm-r m(NITI O

CNt--h n

nh

ao

Nn

N

h ON

^ o'

h

^ h 'o ac

O h oo

ts (N

-' t

tT m rn

oo 'o onm oonoO r-in

- 1-< r-H NO m ^ TJ-

m no

in<N

oo -h(N

^ >riinm -<tnc^h hNHo h

^inff)

<N >-1 - '

»-h <NO i-<i-H

rr0©

C) CI

N©

^ r-.no ro in

cnror-cn ^ 't r-

o

i; no

o

^ io

on

o o m onr-

^ oooo(N oooo

(Nnoon

o Q' 'o oo

Ttw

rt in Mh

9C^ rr'O Tt

dodo ^ rxi- -1^ cs vq

d © »h© *-5©

iOM rn

^-h'o --;i-;OnNO

rt<n h m Q' (N -< ^ rj--; -; NOCO CJ©NrfNOTf

(N-1 Tt « iriin ^Ori voTfrn ^ n S ooiri^ ^ Tt^ NOf<i

't noin10 00h h -H_ n in-^ r-; r^o no^ NO0000NOinink N O

00

- no COn

00O <Nw

rn00- ' iri(fi -H ONoj vo

in ^ ^ ri ^O (NS Tf ^ n

Tt^ rn Jc?

^2 £*

S ^2S

10rnONTt OO(N- h inON00NOON inON(NTJ-

r~-rn

- . no

ri '-1oj r-'0 <nO<d ri ^ o innof-'

o no <N

ONh ^ 00f)

£?005

-' no^ 00 Is

h V)N

^ M

NCH J3!

<N

r*;NONOOn >n-; -; ONr-. ONT) ONO ^ NO(N^ O OON h infSNONONO

OOCNO ri ^ >n^ Tt^Ttcnrn S ri ri "O h rj O H

o ri NO

(Nno

- 1onNO

r-- Onr-rj-00<N (NTfOOOin ONh NOo^ h a<n(N no

hN W

h On

^h ^in

h o vo00 oor-r^-n-oo

1-n >nt)-- Tf

^ in(n 00co

rt(N on no

cnr-no

^ - 1no onin o hh

h ^

(NONn (N NO^<n^Tt00o 00CO

o ONco<N

inin in NO

- 1O On-r-1O <N(-- N£^ 90X O

- ^ ^ - 1in

noin(Nno 00

m0N0N'-H com »-h CN<n Tj- <n nott rr

no

coo in10 noon o - n h noh; 00m Ttin(Nm on ^00^r*»

^in^n ^*"»

ri rj w (N ri (Nri r<i^ ; <n-< <N-^ (N Ttn ri n ri (Nn ^ *-h ^ ^4 i-S

no-; p inONr^NOO NOONinonNO o (Nro(Nj001; n CiO 'C H H

S

Tfri COon

rj-onCO (N- 1fi

iniri - 1S t»

<Nri CNH ^ 00

egnoio ^ no Tt noon

' no --1ri 00

*-<00

,-Hnah

Tf9nw*

^

w

O On^ NO NO-H(N0 on 5 10onno 00 COinOnCO^-<00<N NO® fON© ©

in<Nin

<N ^ ON WOnK Onno(N "2CO^^ COCO00 ^ 00

- 1 CI ^ (N(N00^ NO06fj N ^ fj

^

I

S XJ

c« ^

< $

J3

^3 s

amm m -8

<5 M

U *2 fi Cfl C8

c M & < < -S ®f _ £

'S *c O Q oQ-^ S «q 2

£ ,2 U d § U £ U £03 S o?U o

sg.s * O

s ^ so <s « -a I s ? ^ ^ a I

Qca

<uN O e - < c -rt ^

U 5 > e 'u °2 .2 "5 icco^^-SS^ e* 2 U A "e3

§ 5 tf o

WsOhow § £f2 S o o © So2 ">L§ o

O < £ ^ Z Z < PQ U Q W Z W S w ZUO££ScuH MOOZH

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

162/TheEnergyJournal

is notprojectedto growas fastas China's,butwhosevehicleownership also is

to

projected grownearly twice as fastas per-capitaincome.

The fastergrowth oftotalvehiclesinthenon-OECDcountries willmore

thandoubletheirshareof worldvehicles- from24% in 2002 to 56% by 2030.

Non-OECD countries willacquireoverthree-fourths oftheseadditionalvehicles

- nearly30% will be fromChinaalone. By 2030, therewill be 2.08 billionve-

hicleson theplanet,comparedwith812 millionin 2002; thistotalis 2.5 times

greater thanin 2002.

ShowninFigure8 (forthecountries withpopulation above20 millionin

2002) arethehistoricalgrowth ratesin vehicleownership andper-capita income

(1970-2002),andtheprojectedgrowth ratesfor2002-2030.The historicalresults

for1970-2002showthatvehicleownership in mostcountries grewtwiceas fast

as per-capita income,and in a fewcountries morethantwiceas fast.Such large

income-elasticities forvehicleownership (twoor higher)are consistent withthe

non-linear Gompertz function we haveestimated, forcountries whoseper-capita

incomeis increasing through themiddle-income rangeof$3,000to $10,000.The

projectedresultsto 2030 show thatmostOECD countries'vehicleownership

growthwill deceleratein thefuture, growingat a ratelowerthanper-capitain-

come.However,thenon-OECDcountries whoseper-capita incomeis increasing

through themiddle-income rangewill experiencegrowthin vehicleownership

thatis at leastas rapidas theirgrowth inper-capitaincome.In someofthelargest

countries, vehicleownership willgrowtwiceas rapidlyas per-capita income- in

China,India,Indonesia,andEgypt.

By 2030, thesix countrieswiththelargestnumberof vehicleswill be

China,USA, India,Japan,Brazil,andMexico.Chinais projected tohavenearly20

timesas manyvehiclesin2030 as ithadin2002.Thisgrowth is duebothtoitshigh

rateofincomegrowth andthefactthatitsper-capita incomeduringthisperiodis

associatedwithvehicleownership growing more than twiceas fastas income.

9

Figure puts intohistorical contextthe rapidgrowth thatwe areproject-

ing forChina. In 2002,China's vehicle ownership was 16 per 1000 people,similar

Figure8. GrowthRates forVehicleOwnershipand Per-CapitaIncome

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VehicleOwnership

and IncomeGrowth, 1960-20301 163

Worldwide:

to thatofIndia,butat a higherper-capita income.Thisrateofvehicleownership

was comparableto theratein 1960 forJapan(as well as forSpain,Mexicoand

Brazilin 1960,andalso forSouthKoreain 1982).We projectthatChina'svehicle

ownership will riseto 269 by 2030, increasing2.2 timesfasterthanits growth

rateforper-capitaincome.This projectionforChina,as its per-capitaincome

increasesfrom$4,300to $16,000,is comparableto the1960-2002experience of

Japan,Spain,MexicoandBrazil, and since 1982for South Korea.Although these

othercountries' per-capitaincomesgrewat different (slowerin

rateshistorically

BrazilandMexico,faster inSpain,Japan,andSouthKorea),theirratiosofgrowth

invehicleownership toper-capitaincomegrowth overthe1960-2002periodwere

at leastas highas the2.2 thatwe projectforChina.12

Figure10 summarizes historicaland projectedregionalvaluesfortotal

vehicles.The worldstockofvehiclesgrewfrom122 millionin 1960to 812 mil-

lionin 2002 (4.6% annually),and is projectedto increasefurther to 2.08 billion

by2030 (3.4% annually).The implications forhighwayfueluse arediscussedin

thefollowing section.

Figure9. Historicaland ProjectedGrowthforChina, India, SouthKorea,

Japanand USA: 1960-2030

12.Asobservedintheprevious China's

section, estimated levelforvehicle

saturation ownership

(807)ishigher

than

that forIndia(683).ThisisbecauseChina's density

population isonlyone-third

ofIndia's,

giventhefactthatwedivide population than

bylandarearather habitable

landarea(90%

ofChina's livesinonly30%ofthelandarea).IfweusedIndia's

population lower level

saturation

forChina, forChinain2030would

ourprojections bevehicle of228rather

ownership than 269

vehicles

per1000people,and331million total

vehicles

rather

than 390million.

Thiswould represent

a reduction

intheannualgrowthrate ofvehicle from

ownership 10.6%to10.0%;theratio

togrowth

inper-capita

incomewould be2.07rather than2.2.

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

164/TheEnergyJournal

Figure11 showsthenon-OECD's disproportionately highshareof ad-

ditionalTotalVehiclesrelativeto theirshareof additionalTotalIncomeduring

2002-2030.The non-OECDcountries willproduce62% of theabsoluteincrease

inTotalIncome,butwillconstitute 77% oftheincreaseinTotalVehicles.

5.1 Comparisonto PreviousStudies

Ourvehicleownershipprojections fortheOECD arecomparabletooth-

ersintheliterature,

butaremuchhigherfornon-OECDcountries. Sincecompari-

sonsamongprojectionsarecomplicated

bydifferencesinincomegrowth ratesas-

sumed,we comparetheprojectedratiosof averageannualgrowthrateof vehicle

ownershipto averageannualgrowthrateof per-capitaincomefor2002-2030.

Figure 10. Total Vehicles,1960-2030

Figure 11. RegionalShares oftheAbsoluteIncrease in Incomeand Total

Vehicles,2002-2030

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and IncomeGrowth

VehicleOwnership 1960-20301 165

, Worldwide:

Table 4. ProjectedRatios ofVehicleOwnershipGrowthto Per-capita

IncomeGrowth,2002-2030

Medlock Button

IEA IEA OPEC SMP & Soligo etal.

D-G-S (2004) (2006) (2004) (2004) (2002): (1993)

Region to2030 to2030 to2030 to2025 to2030 1995-2015 2000-2025

OECD 0.42 0.57 0.39 0.40

Non-OECD 1.61 1.12 0.97 1.13

China 2.20 1.38 1.96 1.28 1.42 2.02

India 1.98 0.39 2.25 1.23 2.89

Indonesia 1.89 2.94

Malaysia 1.16 1.96 0.92

Pakistan 1.48 4.00 0.73

Thailand 1.43 2.63

World 0.94 0.61 0.86 0.57 0.59

Table4 comparesourprojections (D-G-S) withthoseofIEA (2004), IEA (2006),

OPEC (2004),theSustainableMobilityProject(SMP, 2004),Buttonet al. (1993)

andMedlock-Soligo(2002).

The respective ratiosfortheOECD aresimilaracrossthestudies.How-

ever,for theNon-OECD countries,ourprojectedratiosare substantiallyhigher

thanthoseofall theothers13 - exceptMedlock-Soligo(2002), whichis discussed

separatelybelow.Fortheworldas a whole,we projectthatvehicleownership will

grow almost as as

rapidly per-capita income, while IEA OPEC

(2004)14, (2004)

andSMP (2004) projectthatitwillgrowonlyaboutsix-tenths as rapidly.

Lowerprojections of Non-OECD vehicleownership by OPEC (2004)

and SMP (2004) can be explainedby theirassumption of low saturationlevels

and low income-elasticitiesof vehicleownership.For OPEC (2004), thedevel-

opingcountries'vehicleownership saturationlevel was assumedto be 425 ve-

hiclesper 1000 people15- considerably lowerthanour saturation estimatesof

700 to 800 formostcountries. ForSMP (2004), therelativelylow projectionsof

13.Exxon Mobil(2005)projections to2030forOECDEurope andNorthAmerica aresimilar

tothoseinTable4: growth in"lightduty" (carsandlight

vehicles isabout

trucks) halfas rapidas

incomegrowth.However, forAsia-Pacific

(bothOECDandnon-OECD combined)theyproject4.7%

annual

growth in"lightduty" while

vehicles, weproject6.1%annual intotal

growth vehiclesforthose

countries,

using comparable income growth assumptions. oftheunderlying

Details model arenot

Wilson

provided. etal.(2004),usingtheDargay-Gately(1999)model,make for

projections China and

India

thataresimilartoours:(car)ownershipgrowthistwiceasrapid income.

asper-capita

14.ThelatestIEAprojections,IEA(2006),aremuch toours

closer toIEA(2004);details

than of

models

theunderlying arenotprovided.

15.SeeBrennand lowsaturation

(2006).Similarly were

levels assumedbyButton etal.(1993),

forcarownership (300to450carsper1000people). Bycontrast,

Dargay-Gately(1999)estimated

levelsof620cars(and850vehicles)

saturation per1000people. etal. (1993)madecar

Button

ownership for

projections tenlow-income twoofwhich

countries, inoursample:

areincluded Pakistan

andMalaysia.They alsomade for1986-2000,

projections which by50%theratio

underestimated of

carownershipgrowth toper-capita

income that

growth actually from

occurred 1986to2000for these

twocountries.

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

166/TheEnergyJournal

Figure 12. ComparisonofIncomeElasticities

non-OECD vehicleownership are due to theirassumption of relativelylow in-

of vehicleownership

come-elasticity (1.3) forlow-to-middle levelsof per-capita

income(through whichmostNon-OECDcountries willbe passinginthenexttwo

decades)- whichis one-third lowerthanourestimated incomeelasticity forthose

incomelevels.SMP (2004) assumessimilarly low income-elasticities vehicle

of

ownership forall incomelevels,whichimpliesmuchlowersaturation levelsthan

we haveestimated.

The highestprojectedratiosforlow-incomeNon-OECD Asian coun-

triesarethoseofMedlock-Soligo(2002). Theyemploya log-quadratic functional

whichhas an income-elasticity

specification, of vehicleownershipthatis very

highat thelowestlevelsof per-capita incomebutwhichdeclinesrapidlyas per-

capitaincomeincreases(Figure12). However,thedata in Figure4 suggestthat

theincome-elasticityof vehicleownership followsa non-monotonic in-

pattern:

creasingoverthelowestincomelevelsthendecreasingas incomelevelsincrease,

butremaining above 1.0 forincomelevelsintherangeof$3,000to $15,000.

To sumupthesecomparisons, theconsiderablylowerprojections ofnon-

OECD vehicleownership in OPEC (2004) and SMP (2004) are due to theiras-

sumption ofsignificantlylowerincome-elasticities andsaturation levelsofvehicle

ownership fortheseregions.Such assumptions raisetheimportant questionof

whydeveloping countries - oncetheyachievelevelsof per-capita incomewithin

therangeof OECD countries overthepastfewdecades- wouldnothavecom-

parablelevelsof vehicleownership. On whatothergoods wouldconsumersin

developing countriesbe spendingtheirincomesinstead?

6. IMPLICATIONS FOR PROJECTIONS OF HIGHWAY FUEL DEMAND

Projectionsof increasingvehicleownershipsuggestthathighwayfuel

However,therateofincreaseinhighwayfuel

use mayalso increasesignificantly.

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VehicleOwnership

and IncomeGrowth,

Worldwide

: 1960-2030/ 167

Figure 13. Gasoline Usage and VehicleOwnershipforSelectedCountries,

1971-2002

demanddependsuponthechangesovertimein fueluse pervehicleas vehicle

increases.

availability

Figure13 summarizes, forseverallargecountries,the 1971-2002rela-

tionshipbetweengasolineusage16and vehicleownership, bothper-vehicle(left

graph)andtotal(rightgraph).At thelowestlevelsof vehicleownership, fueluse

pervehicleis relativelyhigh;a relativelysmallnumber ofvehicles(mostlybuses

andtrucks)areusedintensively. As vehicleownership grows,morecarsandother

personalvehiclesareavailable;theseadditionalvehiclesareusedless intensively

thanbusesandtrucks, so thatfueluse pervehicledeclines,whiletotaluse grows.

Highway fueluse pervehiclealso changesovertimeforotherreasons

thanvehicleavailability,namelyvehicleusage,and fuelefficiency. Witha given

vehiclestock,fuelpriceandincomecan affectvehicleusage(distancedriven)in

a givenyear.Fuel-efficiency improvements can reducefueluse pervehicle,as it

takesless fueltotravela givendistance.

Basedonjudgment andhistorical OPEC (2004) makesassump-

patterns,

tionsaboutdifferent regions' ratesof declinein highwayfuelpervehicle.Using

thoseprojected ratesofdecline17together with ourprojected

growth ratesfortotal

vehicles,we projectthatworldconsumption of highwayfuelwillgrowby2.5%

annuallyby2030: 0.9% intheOECD and5.2% intherestoftheworld.By com-

parison,OPEC (2004) projects2000-2025annualgrowthin worldhighwayfuel

16.Theratio

ofgasoline tototal

consumption vehicles measure

isanimperfect ofhighway fueluse

because

pervehicle, somevehicles

usediesel

fuel

instead andsome

ofgasoline, gasolineisnotusedby

vehicles.

Weuseonly gasoline because

consumption wehavenodatafordieselfuelconsumptionfor

non-OECD orfor

countries, OECDcountriesbefore

1993.Somerecent inGerman

reductions gasoline

usagereflect todiesel

fuel-switching andinBrazil theuseofethanol.

reflect

17.OPEC(2004)projectsthefollowingannualrates forhighway

ofdecline fuelpervehicle:

OECDNorth America:

-0.5%,OECDEurope: -0.6%,OECDPacific:-0.4%,China:-2.1%,Southeast

Asia:-0.9%,SouthAsia:-2.2%,LatinAmerica:-0.7%,AfricaandMiddle East:-1.4%.Weuse

estimates

ofthese

regions'

highwayfuel

pervehiclefromBrennand(2006)tocalculate

highwayfuel

consumptionin2002.

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

168 /TheEnergyJournal

of 1.9%. Ourhigherrateofgrowth inhighwayfuelis due tohigherprojections of

thevehiclestock.If insteadwe wereto assumeslowerprojectedratesof decline

in fuelpervehicle- closerto thoseexperienced in 1990-2000(-0.1% forOECD,

-2% forChinaand SouthAsia,-1% forothernon-OECD)- thenworldhighway

fuelconsumption wouldgrowat 2.8% annually.

If our highprojectedlong-term growthratesof highwayfueldemand

turnouttobe correct, thismaytesttheabilityofproducerstoincreaseproduction.

Givenlimitedincentives fortheOPEC countriesto increaseproduction quickly

(Gately,2004), as well as restrictions

on investment in manycountries, it is not

clearwhether therewill be enoughoil in themarketto matchrisingdemandat

pricestypicaloverthepastseveraldecades.Ifpricesindeedturnouttobe consid-

erablyhigherthanin thepast,highwayfueldemandwillgrowmoreslowlythan

ourprojections, duetoloweruse ofvehicles,higherfuelefficiency,use ofalterna-

tivefuelssuchas bio-dieseland possiblyalso due to reducedvehicleownership

rates.This last effectwouldnotbe capturedby our partialequilibriummodel

of vehicleownership. However,our resultsclearlysupporttheview that,with

current policies,oil demandwill continueto rise significantly

overthecoming

decadesand thereare significant risksthattheoil marketbalanceswill oftenbe

tight;see IMF (2005) fora detaileddiscussion.

7. CONCLUSIONS

We use a comprehensive datasetcovering45 countries over1960-2002

toexplainhistoricalpatternsin vehicle ownership ratesas an S-shaped,Gompertz

functionof per-capitaincome.Our modelspecification exploitsthesimilarity of

response in vehicleownership rates to per-capitaincome across countriesover

time,whileallowingforcross-country variationinthespeedofvehicleownership

growth and in ownership saturation levels.

The relationship betweenvehicleownershipand per-capitaincomeis

highly non-linear.

The income elasticity of vehicleownership startslow butin-

creasesrapidlyovertherangeof $3,000to $10,000,whenvehicleownership in-

creasestwiceas fastas per-capita income.Europeand Japanwereat thisstage

in the 1960's. Manydevelopingcountries, especiallyin Asia, are currentlyex-

periencing similardevelopments and will continueto do so during thenext two

decades.Whenincomelevelsincreasetotherangeof$10,000to$20,000,vehicle

ownership increasesonlyas fastas income.Atveryhighlevelsofincome,vehicle

ownership growth deceleratesandslowlyapproachesthesaturation level.Mostof

theOECD countries areat thisstagenow.

We projectthattheworld'stotalvehiclestockwillbe 2.5 timesgreater

in 2030 thanin 2002, increasing to morethantwobillionvehicles.Non-OECD

countries'shareof totalvehicleswillrisefrom24% to 56%, as theyacquireover

three-fourthsoftheadditional vehicles.China'svehiclestockwillincreasenearly

twenty-fold,to 390 millionby2030 - morevehiclesthantheUSA - eventhough

itsrateofvehicleownership (about270 vehiclesper 1000people)willbe onlyat

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VehicleOwnership

and IncomeGrowth

, Worldwide:

1960-20301 169

levelsexperiencedbyJapanandWestern Europein themid-1970's, andbySouth

Koreain 2001.As in mostcountries, vehicleownership in China,India,Indonesia

andelsewhere willgrowtwiceas rapidly as itsper-capitaincome,as thesecountries

passthrough middle-income levelsof $3,000 $10,000percapita.By 2030,vehi-

to

cle ownershipinvirtually all theOECD countries willhavereachedsaturation, but

inmostofAsia itwillstillonlybe at 15% to45% ofownership saturationlevels.

Ourresultsalso suggestthatthefuture strong growth inthevehiclestock

in developingcountries will lead to significantincreasesin oil demandfromthe

transportsector.We projectannualworldwide growth inhighwayfueldemandto

be in therangeof up to 2.5-2.8%.Ourworkhas a numberof otherbroadpolicy

implications.Forexample,developingcountries willfacethechallengeofbuild-

ingtheinfrastructure (roads,bridges,fueldelivery, etc.) neededto supportthe

growthin vehicleownership.Moreover,manyof theenvironmental concerns

associatedwiththegreateruse ofvehiclescouldpresumably be strengthened by

our projections,especiallysince futurevehicleownershipgrowthwill mostly

takeplace in developingcountriesthathave so farbeen able to deal withthe

environmental issues less successfully thanadvancedeconomies(WorldBank,

2002). However,whilethehistorical patterns in vehicleownership ratessuggest

thatgrowingwealthis a powerful determinant of vehicledemand,policymakers

maybe able to slowtheexpansionofthevehiclestockthrough taxpolicies,pro-

motionof publictransport, and appropriate urbanplanning- an important area

forfuture research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authorswishto thankKarl Storchmann, two anonymous referees

and theeditorforhelpfulsuggestions.Paul Atang,StephanieDenis,andAngela

Espirituprovidedexcellentresearchassistance.

REFERENCES

Button,

Kenneth,Ndoh Ngoe,andJohn Vehicle

Hine(1993)."Modeling Ownership andUseinLow

IncomeCountries."JournalofTransportEconomicsandPolicy.

January:51-67.

Brennand,

Garry. Sector

"Transportation attheOPECSecretariat."

Modeling WorkshoponFuelDe-

mand Modeling intheTransportation

Sector.

Vienna. 20th 2006.

January;

Dargay,

Joyce(2001). "TheEffectofIncomeonCarOwnership:EvidenceofAsymmetry".Transpor-

Research

tation , PartA.35:807-821.

andDermot Gately (1999)."Income's

Effect

onCarandVehicle Worldwide:

Ownership, 1960-

2015." Research,

Transportation Part

A33:101-138.

Dermot

Gately, (2004)."OPEC'sIncentivesforFaster Growth."

Output TheEnergyJournal

25(2):

75-96.

Exxon Mobil.2005Energy Outlook.December2005.http://www.exxonmobil.com/Corporate/Cit

zenship/Imports/EnergyOutlook05/2005_energy

_outlook.pdf

International

Energy Agency(IEA).World Outlook

Energy 2004.Paris.

, World

Energy 2006.Paris.

Outlook

International

Monetary Fund(IMF,2005):"WilltheOilMarketContinue toBeTight?," IV

Chapter

ofWorldEconomic Outlook,April.

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

170/TheEnergyJournal

Kenneth

Medlock, B.Ill,andRonald "Automobile

(2002).

Soligo OwnershipandEconomicDevelop-

ment:Forecasting

PassengerVehicle

Demand totheyear2015."

Journal Economics

ofTransport

andPolicy.

36(2):163-188.

MJH(1983).TheCarMarket:

Mogridge A StudyoftheStatics

andDynamics ofSupply-Demand

London:

Equilibrium. Pion.

ofthePetroleum

Organization Countries

Exporting (OPEC,2004).OilOutlookto2025.OPECRe-

view

paper.

Karl(2005).Long-run

Storchmann, Gasoline

Demand forPassenger

Cars:TheRoleofIncomeDis-

tribution."

EnergyEconomics. 27(1):25-58.

January,

Sustainable

Mobility (2004).

Project 2030:Meeting

Mobility theChallenges

toSustainability.

World

Business

CouncilforSustainableMobility.

Wilson,

Dominic,Roopa Purushothaman,andThemistoklis

Fiotakis

(2004)."TheBRICsandGlobal

Markets:

Crude,CarsandCapital."GlobalEconomicsPaperNo.118.NewYork: GoldmanSachs.

WorldBank.Cities

ontheMove. August 2002.http://www.worldbank.org/transport/urbtrans

on_the_move.pdf

USDepartmentofEnergy (2006).International

EnergyOutlook2006.Washington.

APPENDIX A: DATA SOURCES

Thisappendixprovidesfurther detailson thedatasetsusedin theanaly-

sis ofvehicleownership.

Data on vehicles(at leastfourwheels,including cars,trucks,andbuses)

are primarily fromthe UnitedNationsStatisticalYearbook.The data fora few

country-years arefromthenationalstatistical offices.

Historicaldataon Purchasing-Power-Parity (PPP) adjustedgrossdomes-

ticproduct arefromtheOECD's SourceOECDdatabase.Thedataareexpressedin

thousands of 1995PPP-adjusted dollars.Wherenecessary, theserieswerespliced

withreal incomedatafromIMF's WorldEconomicOutlookdatabaseusingthe

assumption thatgrowth in thePPP GDP rateequalsrealincomegrowth.

Data on thereal incomegrowthprojectionsfor2005-09 are fromthe

IMF's WorldEconomicOutlook.For 2010-30,themaindata sourceis theU.S.

Department of Energy(DoE) International EnergyOutlookApril2004. An ad-

justment was madeto theDoE's growthprojection forChinaand India.In both

cases, thelong-term incomegrowthrateswerereducedby 1 percentagepoint

(specificallyforChina,thegrowth rateis 5.0 percentannuallyover2010-14,4.4

percentover2015-2019,and 4.1 percentover2020-2030;forIndia,thegrowth

rateassumption is 4.3 during2010-2014,4.1 percentduring2015-2019,and 3.9

during2020-2030).Thisadjustment was madetoreducethePPP-weighted world

growth rateto itshistorical averageof about3.5 percenta year.This adjustment

maycreatea downward bias in ourvehiclesprojection if,in thefuture,

worldin-

comegrowth willturnoutto be higherthanthehistorical average.

Thedataon urbanization andlandareaarefromtheWorldBank's World

Development Indicatorsdatabase.Urbanization is expressedin percentagepoints

andlandareais expressedinsquarekilometers. The dataon population, including

projections,arefromtheUnitedNationsdatabase(medianscenario).Population

density was calculatedbydividing totalpopulation bylandarea;itis measuredby

personspersquarekilometer.

This content downloaded from 66.194.176.171 on Wed, 15 Oct 2014 06:41:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- PADI Rescue Diver - Blank Knowledge ReviewDocument13 pagesPADI Rescue Diver - Blank Knowledge ReviewAj Quek67% (3)

- Autonomous Cars and Public Transport: An Opportunity ResponseDocument16 pagesAutonomous Cars and Public Transport: An Opportunity ResponseHSumptNo ratings yet

- SVE Event GuideDocument22 pagesSVE Event GuideMadalina MarinacheNo ratings yet