Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Understanding and Enacting Technology Me

Uploaded by

hilmanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Understanding and Enacting Technology Me

Uploaded by

hilmanCopyright:

Available Formats

THE JOURNAL OF ASIA TEFL

Vol. 19, No. 3, Fall, 2022, 1024-1032

http://dx.doi.org/10.18823/asiatefl.2022.19.3.17.1024

The Journal of Asia TEFL

http://journal.asiatefl.org/

e-ISSN 2466-1511 © 2004 AsiaTEFL.org. All rights reserved.

Understanding and Enacting Technology-Mediated Task-Based

Language Teaching in Their Classrooms: The Voice of Indonesian

In-Service English Teachers

Elih Sutisna Yanto

Universitas Singaperbangsa Karawang, Indonesia

Muhammad Reza Pahlevi

Universitas Singaperbangsa Karawang, Indonesia

Hilmansyah Saefullah

Universitas Singaperbangsa Karawang, Indonesia

Introduction

Language pedagogy should help students communicate effectively in the target language. Schools have

applied the communicative agenda in different ways. One such realization is task-based language

instruction (hereinafter TBLT). TBLT is a “learner-centered approach to language education (e.g., Van

den Branden et al., 2009, p. 3). Given the many definitions of tasks and the distinctiveness of task

performance in technology-enhanced environments, it is critical to operationalize what we mean by tasks

in this review. Samuda and Bygate (2008) define a task as “a holistic activity that integrates language use

to attain a non-linguistic objective while facing a linguistic challenge, with the overarching aim of

increasing language learning, through process or product or both” (p. 69). In addition, Ellis and Shintani

(2014, p. 135) define TBLT as an approach that “aims to develop learners’ communicative competence

by engaging them in meaning-focused communication through the performance of tasks.” On the same

page, they add that “a key principle of TBLT is that even though learners are primarily concerned with

constructing and comprehending messages, they also need to attend to form for learning to take place.”

The present study identifies in-service English teachers’ understanding and performance of

Technology-Mediated Task-Based Language Teaching (hereafter TMTBLT) in their classrooms.

Moreover, the study aims to assist in-service English teachers in designing and implementing

Technology-Mediated Task-Based Language Teaching (TMTBLT) in their classrooms. Finally, the study

investigates the in-service English teachers’ reflections on the change in their practice in implementing

TMTBLT in their classroom. Therefore, the current research endeavours to address the following research

questions:

1. Are Indonesian in-service English teachers familiar with TMTBLT Instruction?

2. What are in-service teachers’ responses after participating in three workshops in TMTBLT?

2022 AsiaTEFL All rights reserved 1024

Elih Sutisna Yanto et al. The Journal of Asia TEFL

No. 3, Fall 2022, 1024-1032

Theoretical Framework

The key terms describing the core of TBLT are “tasks” and “learners.” Although there are variances in how

researchers in the field conceptualize tasks and TBLT, they all agree on a set of key features that define what a

task is. Gonzalez‐Lloret (2017) emphasizes three points about tasks. First, tasks are meaning-oriented and

communicative. They focus on the content of the message rather than the language. This means that tasks

should be goal-oriented and as authentic as possible, integrating real-world contextualized language with

technology that may be used outside of the activity. Second, the success of the learner on tasks is considered if

she or he is successful in doing the task and completing the assignment in the language rather than learning a

specific linguistic element. A key principle of TBLT is the idea of doing something with the language rather

than simply knowing something about it. The TBLT methodology, which suggests that a language can be

acquired by involving learners in its use, is based on learning by doing or experiential learning (Dewey, 1997).

Finally, the primary purpose of TBLT is language acquisition rather than communicative efficiency. Followers

of TBLT distinguish between learners' development of communicative abilities in language usage and their

language acquisition. The major aim of TBLT is how activities, and more broadly a task-based syllabus, may

facilitate students' learning of new languages. The purpose of TBLT is to support language acquisition at three

levels: fluency, accuracy, and complexity. These three dimensions serve as benchmarks for assessing language

acquisition achievement, which goes beyond success on any single task.

A number of researchers have emphasized the necessity of task design and task-based learning and teaching

in light of the unique affordances and features available in computer-mediated contexts (e.g., Chapelle, 1998;

Doughty & Long, 2003; Hampel, 2006; Rosell-Aguilar, 2005; Skehan, 2003). However, to date, there has been

limited investigation into how technology-mediated tasks are understood and performed in the classroom by in-

service English teachers in the Indonesian context. To fill this void, this study examines in-service English

teachers' understanding and enactment of TMTBLT.

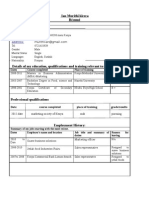

Methodology

The present study aims to investigate in-service English teachers’ understanding and performance of

TMTBLT in their classrooms during the COVID-19 pandemic. To achieve this, a critical participatory

action research method was used (see Table 1). The use of such research design would help obtain

comprehensive answers.

The first author's responsibilities include writing research questions; preparing the workshop series and

associated instruments; determining research paradigms; reviewing the literature review; collecting data;

and preparing consent forms. The second and third authors help the first author gather and organize data

and find references.

Participants

The participants in the study were Indonesian in-service English teachers from different secondary

schools. The TMTBLT webinars were offered to over 200 Indonesian in-service English teachers from

different secondary schools. Only 20 participants (female: n = 15, male: n = 5) were interested in

participating in the webinar and the survey. The online questionnaires (see Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and

Table 5) were sent by email to 20 participants before and after they participated in the TMTBLT

workshops. The data was collected from 20 in-service English teachers from 15 schools situated in six

districts of West Java, Indonesia, who share Indonesian as their L1. Due to the number of in-service

teachers involved, this is a very limited number of participants, but this study should provide a starting

point for more in-depth research. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the authors interviewed ten of the

participants who have taught at least two semesters through apps-mediated online ELL and participated in

two TMTBLT webinars and the face-to-face workshop mentored by the first author. Within the consent

2022 AsiaTEFL All rights reserved 1025

Elih Sutisna Yanto et al. The Journal of Asia TEFL

No. 3, Fall 2022, 1024-1032

form, all participants were informed about how their confidentiality and privacy would be kept. Those

who did not volunteer faced no penalties, and fortunately, none of them withdrew from the research.

Data Collection Instruments and Data Analysis

To collect data for the specified questions, a survey was developed based on Jeon and Hahn's (2006)

Teacher Questionnaire. It assessed EFL teachers' perceptions of TMTBLT in terms of perspectives on

knowledge of TMTBLT instruction, their responses to their previous TMTBLT and after two webinar

sessions, their response to understanding of task and TBLT, as well as their views on implementing

TMTBLT. Data was also collected qualitatively using semi-structured interviews. Throughout the

interviews, prompt questions were also used to elicit more information on the subject under investigation.

The collected data was analysed using a set of predefined procedures. To begin with, the data was

transcribed. Next, the transcribed data was read numerous times and grouped according to themes. Then,

it was re-read, and the final categorizations under each theme were made. Finally, the data saturation was

estimated, and thematic saturation was reached. (Lowe et al., 2018).

TABLE 1

Stages of AR (Adapted from Dikilitaş and Griffiths (2017))

Stages Activities

Stage 1: discussion and identification of research problems with all of the

Develop a Plan of Action researchers;

establishing research questions;

discussion and planning the workshop series of TMTBLT for in-

service English teachers;

determining research paradigms;

reviewing the relevant literature;

discussion and deciding on data collection methods;

discussion and preparing tools for data collection (pre-survey, post

survey, semi-structured interview, and reflection);

obtaining consent and dealing with other ethical procedures;

a. Workshop series of filling the pre-survey questionnaires of TMTBLT;

TMTBLT for in-service introducing in service English teachers to the nature of TBLT and

English teachers TMTBLT in English Language Teaching (ELT);

showcasing some best practices in implementing TMTBLT in ELT;

b. Teachers’ exploration & facilitating teachers in in designing a lesson plan of TMTBLT;

implementation of showing and guiding them how to write a TMTBLT lesson plan;

Stage 2: TMTBLT

Act to c. Teaching English using asking teachers to teach their students using TMTBLT;

Implement TMTBLT

the Plan d. Reflection and filling the asking and helping teachers reflect on their teaching practice using

post survey TMTBLT which had been conducted;

questionnaires of

TMTBLT

e. Collecting data inviting teachers to complete a questionnaire;

asking them to participate in a semi-structured interview;

f. Sorting the data sorting the data from the questionnaire and interview that were

relevant to the focus of research.

Stage 3: carrying out the analysis procedures by coding all collected data

Observe the effects of action in the and identifying themes qualitatively;

context

Stage 4: answering the research questions with the evidence from the data;

Interpret the results drawing out implications;

considering limitations of the study;

looking into the future by providing future research agenda that has

not been investigated yet in this study;

2022 AsiaTEFL All rights reserved 1026

Elih Sutisna Yanto et al. The Journal of Asia TEFL

No. 3, Fall 2022, 1024-1032

Findings and Analysis

This section presents the findings and the discussion of the thematic data analysis. In the discussion

section, the results are presented on four themes: knowledge of TMTBLT instruction and responses to

TMTBLT from before and after two webinar sessions, response to understanding of task and TBLT, and

teachers’ view on implementing TMTBLT. Both quantitative and qualitative data are compared,

combined, and discussed.

Teachers’ Knowledge of TMTBLT Instruction Before Participating in the

TMTBLT Workshop Series

TABLE 2

In-Service Teachers’ Responses to the Pre-Survey

Questionnaire items Teachers’ Responses Mean Standard

Strongly Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly deviation

disagree Agree

1. I do not know about 3 (15%) 9 (45%) 3 (15%) 4 (20%) 1 (5%) 3.45 1.1

TMTBLT as an approach

in teaching and learning

English

2. I have not yet taught 3 (15%) 8 (40%) 4 (20%) 4 (20%) 1 (5%) 3.30 1.13

English using TMTBLT.

3. I do not have any 6 (30%) 6 (30%) 4 (20%) 3 (15%) 1 (5%) 3.6 1.31

learning experiences with

TMTBLT as an approach

in teaching and learning

English before

participating in the

workshop series

4. I have no ideas, 4 (20%) 7 (35%) 4 (20%) 2 (10%) 3 (15%) 3.4 1.35

enthusiasm, or

confidence in using

TMTBLT in my

classroom because I have

yet to learn from an

expert in this field since

becoming an English

teacher.

5. There is no English 3 (15%) 8 (40%) 5 (25%) 2 (10%) 2 (10%) 3.4 1.23

teaching and learning

approach with TMTBLT

in my school

Table 2 deals with the teachers’ responses to the pre-survey (before participating in the TMTBLT

workshops). The results show that, in response to Q1, approximately twelve teachers or 60% of

participants reported that they knew of TMTBLT as an English pedagogical approach. Six teachers said

they self-studied TBLT by attending “conferences” and reading “articles and books,” while six said they

had “formal instruction” in TBLT. Five participants knew nothing about TBLT. Only 60% of participants

felt they had a high level of TMTBLT knowledge through self-study and formal instruction. Q2 and Q3

investigated the teachers’ experiences in teaching English using TMTBLT. Four (20%) participants did

not have experience of teaching English with TMTBLT. Twelve participants (60%) reported that they had

experience. Q4 investigated the teachers’ ideas, enthusiasm, and confidence in using TMTBLT. 11 (55%)

of the 20 participants had ideas, enthusiasm, and confidence in TMTBLT, but only 5 had training. Q5

asked the teachers if their schools implemented TMTBLT in English teaching and learning. Eleven (55%)

said they used TMTBLT as a method of teaching English. Only 4 (20%) of the participants did not use it.

From those data findings, it can be inferred that teachers’ self-development and previous knowledge on

2022 AsiaTEFL All rights reserved 1027

Elih Sutisna Yanto et al. The Journal of Asia TEFL

No. 3, Fall 2022, 1024-1032

TBLT have a crucial role in the implementation of TMTBLT in the classroom. It can be seen that self-

study and formal instruction encourage the teachers to implement TMTBLT in their classroom and have

positive attitudes to that teaching approach.

Teachers’ Responses to TMTBLT After Participating in Three Workshops

TABLE 3

In-Service Teachers’ Responses to the Post-workshop Survey

Questionnaire items Teachers’ Responses Mean Standard

Strongly Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly deviation

disagree Agree

1. I have better 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 2 (10%) 15 (75%) 3 (15%) 4.05 0.51

knowledge and

understanding about

TMTBLT as an

approach in teaching

and learning after

participating in the 3-

day workshop series.

2. I have a better skill in 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 1 (5%) 19 (95%) 0 (0%) 3.95 0.22

implementing

TMTBLT in my

classroom.

3. I have more learning 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 7 (35%) 7 (35%) 6 (30%) 3.95 0.83

experience with

TMTBLT as an

approach in teaching

and learning English

after participating in

the workshop series.

4. I have more ideas, 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 2 (10%) 16 (80%) 2 (10%) 4.05 0.51

enthusiasm, and

confidence in using

TMTBLT as an

approach in teaching

and learning English

after I learned about it

in this workshop

Table 3 deals with the teachers’ responses to the post-workshop survey. The results show that, in

response to Q1, 90% of participants reported that they had better knowledge of TMTBLT after

participating in the workshop. In this study, the majority of teachers (19 teachers) claimed to have better

skills in creating instructional design of TMTBLT. Thirteen participants said they had more learning

experience with TMTBLT. Furthermore, after attending the workshop, 18 (90%) participants claim to

have more ideas and enthusiasm for using TMTBLT as an approach in English teaching and learning.

To this end, for example, Teacher 1 said that “materials in textbooks are not suited for use with task-

based learning techniques” and that “large class sizes remain a challenge to the application of task-

based learning methods.” Inexperienced teachers have little expertise in task-based education, and

students are not used to task-based instruction.

Based on the findings, it can be inferred that the teaching workshop on TMTBLT provides the teachers

with better understanding, skills, and experience in applying TMTBLT in their English classroom. The

teaching workshop also encourages the teacher to use TMTBLT for their English instruction, and they

also have positive attitudes toward this approach.

2022 AsiaTEFL All rights reserved 1028

Elih Sutisna Yanto et al. The Journal of Asia TEFL

No. 3, Fall 2022, 1024-1032

TABLE 4

In-Service Teachers’ Response to the Understanding of Task and TBLT

Questionnaire items SA A U D SD Mean Standard

deviation

1. A task is a directed 11 (55%) 9 (45%) 0 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 4.55 0.51

communicative goal.

2. A task involves a primary 10 (50%) 8 (40%) 2 (10%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 4.4 0.68

focus on meaning.

3. A task has a clearly defined 8 (40%) 11 (55%) 1 (5%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 4.35 0.59

outcome.

4. A task is an activity where 7 (35%) 11 (55%) 2 (10%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 4.25 0.64

learners use the target

language.

5. TBLT agrees with 8 (40%) 12 (60%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 4.4 0.50

communicative language

teaching principles.

6. TBLT is based on the 11 (55%) 9 (45%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 4.6 0.5

student-centred instruction

approach.

7. TBLT includes pre-task, 9 (45%) 10 (50%) 1 (5%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 4.4 0.6

task, and post-task

implementation.

Table 4 deals with the teachers’ response to the understanding of task and TBLT. The results show that,

in answer to Q1 to Q7, more than 90% of participants agreed that: (1) a task is a communicative goal that

has been provided; (2) the major focus of an activity is on meaning; (3) the objective of a task is well-

defined; (4) a task is an activity in which the target language is used by learners; (5) TBLT is in

agreement with the principles of communicative language teaching; (6) student-centred learning is the

foundation of TBLT; and (7) TBLT covers pre-task, task, and post-task implementation.

The data from Table 4 deals with the teachers’ understanding of “task” and TBLT after they have

attended the teaching workshop on TMTBLT. All of their responses are in agreement with the principles

of TBLT. Therefore, the workshop successfully provides relevant knowledge about TBLT.

TABLE 5

In-Service Teachers’ Views on Implementing TMTBLT

Questionnaire items SA A U D SD Mean Standard

deviation

8. I have interest in 10 (50%) 10 (50%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 4.50 0.51

implementing TMTBLT in the

classroom.

9. TMTBLT provides a relaxed 7 (35%) 12 (60%) 1 (5%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 4.30 0.57

atmosphere to promote EFL use.

10. TMTBLT actives learners’ 7 (35%) 13 (65%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 4.35 0.49

needs and interest.

11. TMTBLT pursues the 8 (40%) 11 (55%) 0 (0%) 1 (5%) 0 (0%) 4.35 0.75

development of the integrated

skills.

12. TMTBLT is a psychological 7 (35%) 10 (50%) 0 (0%) 3 (15%) 0 (0%) 4.05 1

burden for the teacher as a

facilitator.

13. TMTBLT needs more 7 (35%) 12 (60%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 1 (5%) 4.20 0.89

preparation time than other

approaches.

14. TMTBLT is proper for 6 (30%) 14 (70%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 4.30 0.47

controlling classroom

arrangements.

15. TMTBLT materials should 8 (40%) 12 (60%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 4.40 0.50

be meaningful and purposeful, as

well as based on real-world

context.

2022 AsiaTEFL All rights reserved 1029

Elih Sutisna Yanto et al. The Journal of Asia TEFL

No. 3, Fall 2022, 1024-1032

Table 5 deals with teachers’ views on implementing TMTBLT. The results show that, in answer to Q8

to Q15, more than 90% of participants agreed that: (1) TBLT is something they would like to try out in

the classroom; (2) TMTBLT creates a friendly atmosphere for English language learners; (3) TMTBLT

focuses on the interests and needs of students; (4) It is TBLT's goal to develop a wide range of

interconnected skills; (5) A teacher's role as a facilitator of TMTBLT is psychologically challenging; (6)

Preparation time for TMTBLT is longer than for other methods; (7) TMTBLT is an appropriate approach

for controlling the arrangement of a classroom; and (8) TMTBLT materials should be relevant to the real-

world context in which they are used. From the findings, it can be concluded that most teachers have

positive views on implementing TMTBLT after they have attended the workshop.

One teacher said that traditional classroom instruction may be “monotonous.” Instead, she uses

TMTBLT to liven it up. She claims that TMTBLT can help students become more engaged and motivated

in class. She stated that

TMBLT is a technique I use to raise the energy level and build curiosity in a room. As a result,

students may get the impression that studying English is really rather enjoyable. It has the potential

to correct a problem in the conventional teaching style.

Discussions and Conclusions

This research examines in-service English teachers' understanding and use of Technology-Mediated Task-

Based Language Teaching (TMTBLT). The project also aims to help in-service English teachers create and

implement TMTBLT in their classrooms. Finally, the research examines in-service English teachers'

perspectives on their classroom use of TMTBLT. The majority of the participants who participated in this

research had positive attitudes toward, and highlighted numerous benefits of the application of TMTBLT in

their classroom. In a similar vein, Azis and Husnawadi (2020), based on their research, argue that the nature

of collaborative learning and the affordances of task design make students feel more confident when using

English. However, a number of participants stated their problems with implementing the TMTBLT

approach. The drawbacks of TMTBLT are that textbook contents are not well adapted for use with task-

based learning strategies, and high-class size is still a burden in the implementation of task-based learning

methods. Task-based education is unfamiliar territory for many inexperienced teachers, and students are not

accustomed to task-based educational contexts. This is in accordance with a study from Liu, Mishan, and

Chambers (2018) that revealed limited knowledge of task-based language teaching and learning in the

educational context has been a key barrier to its implementation. Furthermore, TMTBLT has problems

providing students with easy-to-use tools and a stable internet connection. Teachers believe that

incompatible devices produce tech-based learning problems. Students lacked the technology required for

task-based language teaching. Teaching should incorporate materials and technologies based on tasks.

Gonzalez-Lloret (2017) argues that “the approach to curriculum design known as task-based language

teaching (TBLT) is appropriate for informing and realizing the full potential of technology breakthroughs

for language acquisition” (p.234). The key aspects of the nature of technology-mediated activities include

how they must be constructed, executed, and evaluated in order to be used effectively in language-learning

tasks (Gonzalez-Lloret, 2017).

Accordingly, Smith and González-Lloret (2020) claim that TMTBLT has the potential to make

language learning more accessible. The incorporation of technology-mediated tasks could have

significant long-term benefits for students. The lives of students could be improved if they knew how to

use technology to find and obtain employment online. This includes searching for jobs on the appropriate

websites; writing and submitting applications; creating a video resume; and performing well in a video-

based job interview. To begin, it is necessary to acknowledge the wider variety of studies into different

aspects of TMTBLT that are currently taking place in many different places around the world. This

variety of research is constantly expanding. This variety of research is constantly expanding.

2022 AsiaTEFL All rights reserved 1030

Elih Sutisna Yanto et al. The Journal of Asia TEFL

No. 3, Fall 2022, 1024-1032

The results of investigations of various aspects of task implementation and usage help us to take

incremental strides forward in our knowledge and understanding of the topic. Numerous studies illustrate

the effectiveness of tasks in promoting Second Language Acquisition. This empirical study is critical and

must be conducted indefinitely.

Before implementing any policy, extensive surveys and research on teachers' viewpoints should be

conducted and analysed. This was part of the study's rationale, but our sample size was limited. It is well

acknowledged that teachers' opinions are crucial in the realization of any curricular innovation (Graves &

Shoen, 2006). To conclude, it is critical to investigate teachers' opinions and attitudes before

implementing any policy.

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by Universitas Singaperbangsa Karawang, Indonesia under The Institution

of Research and Community Service (261.47/SP2H/UN64.10/LL/2021). We would like to express our

gratitude to the language teachers for their willingness to collaborate with us. We appreciate the

anonymous reviewers' contributions to earlier drafts of this article.

The Authors

Elih Sutisna Yanto (corresponding author) holds a Master of Arts in English Education from

Universitas Profesor DR. Hamka, Jakarta. He is also a certified master teacher trainer and an English

Language instructor. His research interests include language teaching methodology, systemic functional

linguistics in language education and the use of corpus in teaching grammar.

English Education Department, Faculty of Teacher Training Education,

Universitas Singaperbangsa Karawang

Jawa Barat, Indonesia

Email: elih.sutisna@fkip.unsika.ac.id

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0701-6454

Muhammad Reza Pahlevi is an English lecturer at Universitas Singaperbangsa Karawang, West Java,

Indonesia. He obtained a Master of Arts degree in English Education from Universitas Negeri Surabaya.

He also contributes on writing articles in ELT. His professional interests include research methodology,

language course design, and task-based language teaching.

English Education Department, Faculty of Teacher Training Education,

Universitas Singaperbangsa Karawang

Jawa Barat, Indonesia

E-mail: mreza.pahlevi@fkip.unsika.ac.id

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3061-6637

Hilmansyah Saefullah is a lecturer at Universitas Singaperbangsa Karawang, West Java, Indonesia. He

earned his Master of Arts degree in English Education from Indonesia University of Education (UPI). His

professional interests include task-based language teaching and literature in ELT.

English Education Department, Faculty of Teacher Training Education,

Universitas Singaperbangsa Karawang

Jawa Barat, Indonesia

E-mail: hilmansyah.saefullah@fkip.unsika.ac.id

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4729-6083

2022 AsiaTEFL All rights reserved 1031

Elih Sutisna Yanto et al. The Journal of Asia TEFL

No. 3, Fall 2022, 1024-1032

References

Azis, Y. A., & Husnawadi. (2020). Collaborative digital storytelling-based task for EFL writing

instruction: Outcomes and Perceptions. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 17(2), 562-579. https://dx.doi.

org/10.18823/asiatefl.2020.17.2.16.562

Chapelle, C. A. (1998). Analysis of interaction sequences in computer-assisted language learning. TESOL

Quarterly, 32(4), 753-757. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588009

Dewey, J. (1997). Experience and education. Simon & Schuster Touchstone.

Dikilitaş, K., & Griffiths, C. (2017). Developing language teacher autonomy through action research.

Springer Nature.

Doughty, C., & Long, M. (2003). Optimal psycholinguistic environments for distance foreign language

learning. Language Learning & Technology, 7, 50-80.

Ellis, R., & Shintani, N. (2014). Exploring language pedagogy through second language acquisition

Research. Routledge.

González-Lloret, M. (2017). Technology for task‐based language teaching. In C. A. Chapelle & S. Sauro

(Eds.), The handbook of technology and second language teaching and learning (pp. 234-247).

John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118914069.ch16

Graves, V., & Shoen, B. (2006). Innovatability analysis teachers in task-based language education. The

Electronic Journal for English as a Second Language, 16(4), 1-21.

Hampel, R. (2006). Rethinking task design for the digital age: A framework for language teaching and

learning in a synchronous online environment. ReCALL, 18(01), 105-121. https://doi.org/10.1017/

s0958344006000711

Jeon, I., & Hahn, J. (2006). Exploring EFL teachers’ perceptions of task-based language teaching: A case

study of Korean secondary school classroom practice. Asian EFL Journal, 8(1), 123-143.

Liu, Y., Mishan, F., & Chambers, A. (2018). Investigating EFL teachers’ perceptions of task-based

language teaching in higher education in China. The Language Learning Journal, 49(2), 131-146.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2018.1465110

Lowe, A., Norris, A. C., Farris, A. J., & Babbage, D. R. (2018). Quantifying thematic saturation in

qualitative data analysis. Field Methods, 30(3), 191-207. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822x17749386

Rosell-Aguilar, F. (2005). Task design for audiographic conferencing: Promoting beginner oral

interaction in distance language learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 18(5), 417-442.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09588220500442772

Samuda, V., & Bygate, M. (2008). Tasks in second language learning. Palgrave Macmillan.

Skehan, P. (2003). Focus on form, tasks, and technology. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 16(5),

391-411. https://doi.org/10.1076/call.16.5.391.29489

Smith, B., & González-Lloret, M. (2020). Technology-mediated task-based language teaching: A research

agenda. Language Teaching, 54(4), 518-534. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0261444820000233

Van den Branden, K., Bygate, M., & Norris, J. (2009) Task-based language teaching: Introducing the

reader. In K. Branden, M. Bygate, & J. Norris (Eds.), Task-based language teaching: A reader (pp.

1-13). John Benjamins.

(Received June 17, 2022; Revised August 23, 2022; Accepted Sep 18, 2022)

2022 AsiaTEFL All rights reserved 1032

You might also like

- DepEd CI GuidebookDocument244 pagesDepEd CI Guidebookasdfg100% (4)

- Work Systems The Methods Measurement and Management of Work 1St Edition Groover Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument51 pagesWork Systems The Methods Measurement and Management of Work 1St Edition Groover Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFdieulienheipgo100% (8)

- Task-Based Language Teaching in Vietnam MisunderstDocument14 pagesTask-Based Language Teaching in Vietnam Misunderstmikael leeNo ratings yet

- Green Building by Superadobe TechnologyDocument22 pagesGreen Building by Superadobe TechnologySivaramakrishnaNalluri67% (3)

- Task Based Language TeachingDocument13 pagesTask Based Language TeachinglittlesandNo ratings yet

- Task basedlanguageteachingWhateveryEFLteachershoulddo PDFDocument8 pagesTask basedlanguageteachingWhateveryEFLteachershoulddo PDFLara Vigil GonzálezNo ratings yet

- TBLT RP FinalDocument10 pagesTBLT RP FinalImrul Kabir SouravNo ratings yet

- 322-Article Text-1298-1-10-20211201Document6 pages322-Article Text-1298-1-10-20211201Jihan SelasihNo ratings yet

- Proposal For ICT Tools For EFL ClassroomDocument22 pagesProposal For ICT Tools For EFL ClassroomDhawa LamaNo ratings yet

- Utilizing Task-Based Language Teaching in The Improvement of Learner'S Speaking Skills of Bongabong Technical and Vocational High SchoolDocument7 pagesUtilizing Task-Based Language Teaching in The Improvement of Learner'S Speaking Skills of Bongabong Technical and Vocational High SchoolhaniebalmNo ratings yet

- The Application of Interactive Task-Based Learning For EFL StudentsDocument9 pagesThe Application of Interactive Task-Based Learning For EFL StudentsAhmed Ra'efNo ratings yet

- Teachers Perceptions of TBLTDocument12 pagesTeachers Perceptions of TBLTLúciaNo ratings yet

- 1012-Article Text-2005-1-10-20231229Document18 pages1012-Article Text-2005-1-10-20231229Abdul RehmanNo ratings yet

- Teacher Perception About Using Task Based Learning MethodDocument8 pagesTeacher Perception About Using Task Based Learning MethodAlfa Roby MaulanaNo ratings yet

- Perceptions of Teachers Towards The Implementation of Task-Based Language Teaching: A Case Study in A Vietnamese UniversityDocument8 pagesPerceptions of Teachers Towards The Implementation of Task-Based Language Teaching: A Case Study in A Vietnamese Universityhonganh1982No ratings yet

- Project-Based Learning and Problem-Based Learning For EFL Students' Writing Achievement at The Tertiary LevelDocument18 pagesProject-Based Learning and Problem-Based Learning For EFL Students' Writing Achievement at The Tertiary LevelIla Ilhami QoriNo ratings yet

- TESOL Quarterly - 2017 - Kim - Implementation of A Localized Task Based Course in An EFL Context A Study of StudentsDocument29 pagesTESOL Quarterly - 2017 - Kim - Implementation of A Localized Task Based Course in An EFL Context A Study of Students王建文No ratings yet

- The Use of Scientific Approach in Teaching English AsDocument6 pagesThe Use of Scientific Approach in Teaching English AsProfesor IndahNo ratings yet

- Teacher's Code-Switching As Scaffolding in Teaching Content Area SubjectsDocument5 pagesTeacher's Code-Switching As Scaffolding in Teaching Content Area SubjectsJessemar Solante Jaron WaoNo ratings yet

- 224 425 1 SMDocument8 pages224 425 1 SMfebbyNo ratings yet

- Isthestrategyteachable MICELT2018PROCEEDINGS PDFDocument9 pagesIsthestrategyteachable MICELT2018PROCEEDINGS PDFazhari researchNo ratings yet

- 1197 2998 1 PBDocument9 pages1197 2998 1 PBaminhisyam9No ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliografi of Ict ArticlesDocument5 pagesAnnotated Bibliografi of Ict ArticlesMuhammad Rafiq TanjungNo ratings yet

- Difficulties in Implementing Task-Based Language Teaching Perceived by Isp Teachers, Ulis-Vnu Bui Thi Hang, M.ADocument13 pagesDifficulties in Implementing Task-Based Language Teaching Perceived by Isp Teachers, Ulis-Vnu Bui Thi Hang, M.AHuỳnh Lê Hương KiềuNo ratings yet

- Benefits and Implementation Challenges of Task-Based Language Teaching in The Chinese EFL ContextDocument8 pagesBenefits and Implementation Challenges of Task-Based Language Teaching in The Chinese EFL ContextNgọc Điệp ĐỗNo ratings yet

- Go ReviewDocument4 pagesGo ReviewAswini RamachandranNo ratings yet

- N5 Final 001187Document18 pagesN5 Final 001187Gia NguyenNo ratings yet

- 3144-9816-1-PB (4)Document7 pages3144-9816-1-PB (4)hairoriNo ratings yet

- Pre Service EFL Teachers Experiences in Teaching Practicum in Rural Schools in IndonesiaDocument1 pagePre Service EFL Teachers Experiences in Teaching Practicum in Rural Schools in IndonesiaNingsih ThekelandsmNo ratings yet

- A Case Study On Needs Assessment of English Language TeachersDocument5 pagesA Case Study On Needs Assessment of English Language TeachersAnonymous 4iWf3EKNo ratings yet

- Review of English teacher professional development research in SE AsiaDocument14 pagesReview of English teacher professional development research in SE AsiaDEPO KELAPA BANG WAHYUNo ratings yet

- 2 FPW TSL HD KL Ocf 5 M3 HL 8 JFV JSX URt FR TMo 5 M JPJBDocument8 pages2 FPW TSL HD KL Ocf 5 M3 HL 8 JFV JSX URt FR TMo 5 M JPJBliujinglei3No ratings yet

- ANALYSIS TEACHING ENGLISH VOCABULARY TECHNIQUESDocument8 pagesANALYSIS TEACHING ENGLISH VOCABULARY TECHNIQUESWira AgustyanNo ratings yet

- 670-Article Text-1882-1-10-20210606Document22 pages670-Article Text-1882-1-10-20210606Azurawati WokZakiNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Teachers' Implementation of TBLTDocument15 pagesFactors Affecting Teachers' Implementation of TBLTNurindah NurindahNo ratings yet

- Flipped Classroom Learning Model: Implementation and Its Impact On EFL Learners' Satisfaction On Grammar ClassDocument9 pagesFlipped Classroom Learning Model: Implementation and Its Impact On EFL Learners' Satisfaction On Grammar Class21040186No ratings yet

- Tabel MiceDocument11 pagesTabel MiceBuntaraNo ratings yet

- Innovation in Language TeachingDocument2 pagesInnovation in Language Teachingelijahrosejune .ferreraNo ratings yet

- Ewc ProposalDocument7 pagesEwc ProposalIkhmal AlifNo ratings yet

- 708 2503 1 PBDocument10 pages708 2503 1 PBRokia BenzergaNo ratings yet

- Implications of Applied Linguistics for Language TeachingDocument5 pagesImplications of Applied Linguistics for Language TeachingUtamitri67No ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document14 pagesChapter 2Hamzah FansyuriNo ratings yet

- 143 411 1 PB PDFDocument19 pages143 411 1 PB PDFarydNo ratings yet

- Communicative Competence FosteDocument10 pagesCommunicative Competence FosteJanneth YanzaNo ratings yet

- EFL Student Teachers Lesson Planning Processes ADocument20 pagesEFL Student Teachers Lesson Planning Processes AAldana RodríguezNo ratings yet

- EJ1264020Document8 pagesEJ1264020Huy NguyenNo ratings yet

- An Investigation of Act Students English Language Problems and Their Learning Strategies in Grade 10 Bilingual ProgramDocument10 pagesAn Investigation of Act Students English Language Problems and Their Learning Strategies in Grade 10 Bilingual ProgramPreksha AdeNo ratings yet

- Needs Analysis and TBLT For Effective Language LearningDocument11 pagesNeeds Analysis and TBLT For Effective Language Learningapi-272672526No ratings yet

- Group Task - Analyzing Published ArticlesDocument9 pagesGroup Task - Analyzing Published Articlesanisa slbNo ratings yet

- EOAABR IJIOctober2018Vol11No4Document17 pagesEOAABR IJIOctober2018Vol11No4angela castroNo ratings yet

- TPS Final Version Faizah AzzahraDocument14 pagesTPS Final Version Faizah AzzahraFaizah AzzahraNo ratings yet

- An Evaluation of Implementing Task Based Language Teaching TBLT To Teach Grammar To Adolescent Learners in VietnamDocument24 pagesAn Evaluation of Implementing Task Based Language Teaching TBLT To Teach Grammar To Adolescent Learners in VietnamEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Language Teachers' Beliefs and Practices Regarding The Appropriateness of Communicative Methodology: A Case Study From ThailandDocument33 pagesLanguage Teachers' Beliefs and Practices Regarding The Appropriateness of Communicative Methodology: A Case Study From ThailandTay Seng FaNo ratings yet

- IndonesianEFLStudentsAttitudetowardOralPresentations (3)Document17 pagesIndonesianEFLStudentsAttitudetowardOralPresentations (3)nartcognnNo ratings yet

- 1659-ArticleText-3880-1-10-20180122Document9 pages1659-ArticleText-3880-1-10-20180122Gomez Al MuhammadNo ratings yet

- SuratDocument8 pagesSuratfelisha hannisNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Task-Based Language Teaching in Learning MotivationDocument8 pagesThe Effect of Task-Based Language Teaching in Learning MotivationFandom KingdomNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting The Implementation of Communicative Language Teaching Among High School Students of Alaminos City National High SchoolDocument7 pagesFactors Affecting The Implementation of Communicative Language Teaching Among High School Students of Alaminos City National High SchoolJoel Phillip GranadaNo ratings yet

- Teacher's Attitudes Towards Educational Technology in English Language InstitutesDocument10 pagesTeacher's Attitudes Towards Educational Technology in English Language InstitutesMuhammad NaeemNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Task-Based Language Teaching in Learning MotivationDocument9 pagesThe Effect of Task-Based Language Teaching in Learning MotivationmelNo ratings yet

- A Look at EFL Technical Students' Use of Learning Strategies in TaiwanDocument10 pagesA Look at EFL Technical Students' Use of Learning Strategies in TaiwanMuftah HamedNo ratings yet

- Beyond The Curriculum :A Chinese Example of Issues Constraining Effective EnglishLanguage TeachingDocument12 pagesBeyond The Curriculum :A Chinese Example of Issues Constraining Effective EnglishLanguage TeachingYvonne ChiNo ratings yet

- Multilingualism and Translanguaging in Chinese Language ClassroomsFrom EverandMultilingualism and Translanguaging in Chinese Language ClassroomsNo ratings yet

- 2015 The Core Principles of Extensive Reading in An EAP Writing ContextDocument6 pages2015 The Core Principles of Extensive Reading in An EAP Writing ContexthilmanNo ratings yet

- NationDocument10 pagesNationAnonymous BQkF4nmFNo ratings yet

- 2015 The Effectiveness of Core ER PrinciplesDocument6 pages2015 The Effectiveness of Core ER PrincipleshilmanNo ratings yet

- English Education and The Teaching of Literature - 2016Document21 pagesEnglish Education and The Teaching of Literature - 2016hilmanNo ratings yet

- Efl-Teachers-Perception-Towards-Online-Classroom InteractionDocument12 pagesEfl-Teachers-Perception-Towards-Online-Classroom InteractionhilmanNo ratings yet

- The PersonalityDocument7 pagesThe PersonalityMeris dawatiNo ratings yet

- Product+Catalogue+2021+New+Final PreviewDocument34 pagesProduct+Catalogue+2021+New+Final Previewsanizam79No ratings yet

- Otimizar Windows 8Document2 pagesOtimizar Windows 8ClaudioManfioNo ratings yet

- Social Studies Bece Mock 2024Document6 pagesSocial Studies Bece Mock 2024awurikisimonNo ratings yet

- Manual Reductora IVECO TM 265 - TM 265ADocument31 pagesManual Reductora IVECO TM 265 - TM 265ARomà ComaNo ratings yet

- Ch1 - A Perspective On TestingDocument41 pagesCh1 - A Perspective On TestingcnshariffNo ratings yet

- Advantages of Chain Grate Stokers: Dept of Mechanical Engg, NitrDocument3 pagesAdvantages of Chain Grate Stokers: Dept of Mechanical Engg, NitrRameshNo ratings yet

- Rizal's Works Inspire Filipino PrideDocument2 pagesRizal's Works Inspire Filipino PrideItzLian SanchezNo ratings yet

- Gathering Statistical DataDocument8 pagesGathering Statistical DataianNo ratings yet

- Methodology of Legal Research: Challenges and OpportunitiesDocument8 pagesMethodology of Legal Research: Challenges and OpportunitiesBhan WatiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 ProblemsDocument41 pagesChapter 2 ProblemsPrakasam ArulappanNo ratings yet

- PROBLEM 7 - CDDocument4 pagesPROBLEM 7 - CDRavidya ShripatNo ratings yet

- Company Profile Nadal en PDFDocument2 pagesCompany Profile Nadal en PDFkfctco100% (1)

- Cause and Effect Diagram for Iron in ProductDocument2 pagesCause and Effect Diagram for Iron in ProductHungNo ratings yet

- SRFP 2015 Web List PDFDocument1 pageSRFP 2015 Web List PDFabhishekNo ratings yet

- ARP 598, D, 2016, Microscopic SizingDocument17 pagesARP 598, D, 2016, Microscopic SizingRasoul gholinia kiviNo ratings yet

- Occupational Health and Safety ProceduresDocument20 pagesOccupational Health and Safety ProceduresPRINCESS VILLANo ratings yet

- Infineon IKCM30F60GD DataSheet v02 - 05 ENDocument17 pagesInfineon IKCM30F60GD DataSheet v02 - 05 ENBOOPATHIMANIKANDAN SNo ratings yet

- KireraDocument3 pagesKireramurithiian6588No ratings yet

- Materiality of Cultural ConstructionDocument3 pagesMateriality of Cultural ConstructionPaul YeboahNo ratings yet

- Babylonian Mathematics (Also Known As Assyro-BabylonianDocument10 pagesBabylonian Mathematics (Also Known As Assyro-BabylonianNirmal BhowmickNo ratings yet

- Awareness On Biomedical Waste Management Among Dental Students - A Cross Sectional Questionnaire SurveyDocument8 pagesAwareness On Biomedical Waste Management Among Dental Students - A Cross Sectional Questionnaire SurveyIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- PreviewpdfDocument68 pagesPreviewpdfwong alusNo ratings yet

- Pressure Variation in Tunnels Sealed Trains PDFDocument258 pagesPressure Variation in Tunnels Sealed Trains PDFsivasankarNo ratings yet

- Skills and Techniques in Counseling Encouraging Paraphrasing and SummarizingDocument35 pagesSkills and Techniques in Counseling Encouraging Paraphrasing and SummarizingjaycnwNo ratings yet

- Towards Innovative Community Building: DLSU Holds Henry Sy, Sr. Hall GroundbreakingDocument2 pagesTowards Innovative Community Building: DLSU Holds Henry Sy, Sr. Hall GroundbreakingCarl ChiangNo ratings yet

- Assignment 7Document1 pageAssignment 7sujit kcNo ratings yet