Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Comparison of The Plasma Levels of Apolipoproteins B and A-L, and Other Risk Factors in Men and Women With Premature Coronary Artery Disease

Uploaded by

Camilo HernándezOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Comparison of The Plasma Levels of Apolipoproteins B and A-L, and Other Risk Factors in Men and Women With Premature Coronary Artery Disease

Uploaded by

Camilo HernándezCopyright:

Available Formats

Comparison of the Plasma Levels of

Apolipoproteins B and A-l, and Other Risk

Factors in Men and Women with Premature

Coronary Artery Disease

Peter 0. Kwiterovich, Jr., MD, Josef Coresh, PhD, Hazel H. Smith, MT, Paul S. Bachorik, PhD,

Carol A. Derby, PhD, and Thomas A. Pearson, MD, PhD

he plasma levels of total, low-density lipoprotein

The predictors of premature coronary atheroscie-

rosis were examined in 203 patients (66 men

aged 150 years, and 104 women aged 160

T (LDL) and very low density lipoprotein (VLDL)

cholesterols,and triglyceride are usually higher,

whereas those of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cho-

years) undergoing elective diagnostic coronary ar- lesterol and its 2 major subfractions (HDLz and HDL3

teriography. Age, cigarette smoking, hyperten- cholesterols) are usually lower in patients with than in

sion, obesity, diabetes, positive family history of those without coronary atherosclerosis(defined by coro-

premature coronary artery disease (CAD), and nary arteriography).‘-lo In some but not all reports,

plasma levels of total cholesterol, triglyceride, ii- nonlipid risk factors such as increased blood pressure,

poproteins (i.e., very low, intermediate-, low-, and cigarette smoking, diabetes and excess body weight

high-density [HDL] iipoprotehts and their subfrac- were also considered Only approximately half of coro-

tions [HDLe and HDLs], and lipoprotein [a]) and nary artery disease(CAD) is explained by these lipid-

apoiipoproteins (apoA-1, apoA-2 and apoB, re- and nonlipid-related risk factors.‘l Thus, more recent

spectively) were examined using univariate anaiy- studiesalso measuredplasma levelsof apolipoproteins B

ses and multivariate logistic regression. in men, and A-l (apoB and apoA-1; the major proteins of LDL

age (p <O.OS), smoking (p <O.OS), and plasma tri- and HDL, respectively), and lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)], a

glyceride (p <0.02) and apoA-1 (p CO.05) levels plasma lipoprotein consisting of an LDL molecule cova-

were independently associated with CAD. in wom- lently bound to apolipoprotein (a), a protein homolo-

en, smoking (p <O.OOl) and plasma apoB levels (p gous to plasminogen.*-lo However, less comparative in-

<0.04) were the strongest variables independently formation is available in subjects (particularly women)

associated with CAD. it is concluded that the with premature coronary atherosclerosis.

“nontraditional” risk factors (plasma apoA-1 and

apoB levels) are better predictors of premature METHODS

CAD than are plasma lipoproteins and that smok- Study populationr The study population comprised

ing is the strongest of the traditional noniipid risk 99 white men (aged 150 years) and 104 white women

factors. (aged 560 years) who underwent elective, diagnostic

(Am J Cardioi 1662;69:1OlS-1021) coronary arteriography at the Johns Hopkins Hospital

between April 1985 and April 1988. Sixty years was

chosenas the cut point in women, becausethey general-

ly present with premature CAD 10 years later than

men, and very few women aged GO years undergo cor-

onary arteriography.‘,‘*,13The number of nonwhite sub-

jects was too small to constitute a subgroup, and thus

only white subjectswere studied. Patients were excluded

for the following reasons: age, distance (lived >lOO

miles from the Johns Hopkins Hospital), undergoing

unscheduledor emergent cardiac catheterization or cor-

onary angioplasty, receiving lipid-lowering medication

or had a myocardial infarction within the previous 12

weeks.Ninety-three percent of the men, and 91% of the

From the Lipid-Research Atherosclerosis Unit, Departments of Pediat-

women who were eligible and were contacted agreed to

rics, Medicine, and Epidemiology, the Johns Hopkins Medical Institu- participate in the study. Informed consentwas obtained

tions, Baltimore, Maryland. This study was supported by Grant HL from each participant. The study was approved by the

31497 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland. Johns Hopkins Joint Committee on Clinical Investiga-

Manuscript received September 9, 1991; revised manuscript received tion.

and accepted December 11,199 1.

Address for reprints: Peter 0. Kwiterovich, Jr., MD, the Johns Patients were recruited for the study as follows.

Hopkins Medical Institutions, 600 N. Wolfe Street/CMSC 604, Balti- Each week a complete list of age- and sex-eligible pa-

more, Maryland 21205. tients scheduledfor elective arteriography was obtained

PREDICTORS OF PREMATURE CORONARY ATHEROSCLEROSIS 101s

from the catheterization laboratory. Potentially eligible tration (r = 0.018). The HDL cholesterol concentra-

patients were approached systematically, starting with tions in patients were therefore corrected by subtracting

the beginning of the list and proceedingdown. No more 3 mg/dl from the measuredvalues.

than 4 subjects were studied each week, becauseof the HIGH-DENSITY LIPOPROTEIN CHOLESTEROL SUBFRAC-

time limitation posedby the large number of laboratory TIONS: Four milliliters of the heparin-manganesechlo-

analysesneededfor the study. Eighty-eight of the men ride supernate was adjusted to a density of 1.12517and

(88.8%), and 89 of the women (85.5%) underwent angi- centrifuged at 105,000 X g for 40 hours, the bottom

ography for evaluation of ischemic heart disease(typi- fraction containing HDLs was recoveredby tube slicing,

cal angina or a positive exercisetolerance test, or both); and its cholesterolconcentration was determined. HDL2

10%of the men, and 13.5%of the women had arteriog- cholesterol was calculated as the difference betweento-

raphy for valvular heart disease. tal HDL and HDL3 cholesterol.

Definitions of coronary artery disease: To insure VERY LOW,INTERMEDIATE- AND LOW-DENSITY LIPOPRO-

misclassification of <3%,12,13coronary arteriograms TEIN CHOLESTEROLS, AND TRIGLYCERIDE: PlBSIlla (5 ml),

were reviewed by a panel of 3 cardiologists who had no at its own density (1.006 g/ml), and plasma (10 ml)

prior knowledge of the clinical history or laboratory after adjustment to d 1.019 g/ml with liquid potassium

data of patients. The presenceof stenosisin the 15 coro- bromide (17), were centrifuged at 105,000 X g for 18

nary artery segments designated by the American hours. The infranate fractions were collected by tube

Heart Association was determined.i4 CAD was consid- slicing, and their cholesterol contents were determined.

ered to be present if I1 lesion narrowed the lumen of VLDL cholesterol was calculated by subtracting the

any of the 15 coronary arterial segmentsby 150%. Pa- cholesterol in the 1.006g/ml infranate from the plasma

tients with such lesions were considered to be cases, total cholesterol. IDL cholesterol was calculated as the

whereas those without narrowings 150% were consid- difference between the cholesterol in the 1.006 and

ered to be control subjects.The study group was further 1.019 g/ml infranates. LDL cholesterol was calculated

divided into patients with 0, 1, 2 or 3 diseasedcoronary as the difference between the cholesterol in 1.019 g/ml

arteries according to the number of major coronary infranate and total HDL cholesterol. Plasma triglycer-

arteries (right, left anterior descendingor left circum- ide was measuredenzymatically.l 5

flex) that had 150% diameter narrowings). Quantita- APOLIPOPROTEIN MEASUREMENTS: ApoA-1 and ApoB

tive digital methodswere not usedto assessthe extent of levels were measuredby radial immunodiffusion, as de-

coronary atherosclerosis.Visual interpretation of an ar- scribed previously.l5 ApoA-2 was measured in frozen

teriogram generally provides an underestimation of cor- plasma by radial immunodiffusion in 10% agarose,us-

onary atherosclerosis.*Analyses related to risk factors, ing an antibody to apoA-2, and serum pools with known

number of diseasedvessels,and a continuous score of apoA-2 levels obtained as gifts from John Albers, PhD.

CAD will be the subject of a separate report. Plasma was diluted lo-fold and applied to the wells.

Plasma lipid, lipoprotein and apolipoprotein dster- Ring diameters were measuredafter 72 hours. The as-

minations: BLOOD COLLECTION: After a 12-hour fast, say for apoA-2 had a coefficient of variation of 6.1%.

blood (60 ml) was drawn into evacuatedtubes contain- Lp(a) was measured on frozen plasma using a mono-

ing disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (1.5 mg/ clonal antibody-based sandwich enzyme-linked immu-

ml of blood), cooled to 4’C and transported to the nosorbent assay18available commercially (MACRA

Johns Hopkins Lipoprotein Analytical Laboratory. Lp(a) Terumo, Elkton, Maryland). The coefficient of

Cells were removed by centrifugation (1,500 X g, 30 variation for Lp(a) was 6.9%, and the method doesnot

minutes, 4°C) within 3 hours of collection, and plasma detect plasminogen.l8

was stored at 4°C before analysis or at -70°C (for OTHER RISK FACTORS AND CLINtc,4LDAr.4:Interviews

Lp(a) and apoA-2 measurements). Leukocytes were were conducted and clinical data collected using a com-

harvested for isolation of DNA. mon protocol and standardized forms.12~‘g~20 Medica-

TOTALANDHIGH-DENSITY LIPOPROTEIN CHOLESTEROLS: tions used during the preceding 2 weekswere recorded.

Cholesterol in plasma and the lipoprotein fractions was Hypertension was defined as a self-reported history of

determined enzymatically as describedpreviously.15To- high blood pressure,or treatment with antihypertensive

tal HDL cholesterol was determined after precipitation agents. Cigarette smoking was categorized as ever ver-

of the apoB-containing lipoproteins with heparin and sus never smoked. Current smoking was defined as

manganese chloride. When patients were sampled, smoking cigarettes within the past month. Weight and

manganesechloride was used at a final concentration of height (without shoes)were measuredusing a standard

0.046 M; this was changed to 0.092 M for the analysis scaleand recorded to the nearesttenth of a kilogram or

of HDL cholesterol in the relatives of the patients, be- centimeter. Family history of premature CAD (defined

cause the lower concentration does not completely pre- as myocardial infarction [fatal or nonfatal] or angina

cipitate apoB-containing lipoproteins.16To allow a cor- pectoris before the age of 60 years in either parent) was

rection for the incomplete precipitation, a separate obtained by questionnaire.Blood (3 ml) was collected in

substudy was performed in which 188 relatives of pa- fluorinated tubes, and glucose determined at the Johns

tients had HDL cholesterol measured using both con- Hopkins Clinical Chemistry Laboratory using a glucose

centrations of manganesechloride. The lower concen- oxidasemethod. Diabeteswas defined as a fasting blood

tration gave a positive mean bias of 3.1 f 0.3 mg/dl. sugar > 140 mg%*l or a diagnosis of diabetes needing

The bias was independent of HDL cholesterol concen- diet or drug therapy.

1016 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CARDIOLOGY VOLUME 69 APRIL 15, 1992

TABLE I Characteristics of Subjects Undergoing Coronary

Arteriography for Premature Atherosclerosis

rTABLE II Medication Use by Subjects

Medications Taken Men Women Total

Men Women in Previous 2 Weeks (n = 97) (n = 103) (n = 200)

(n = 99)* (n = 104)*

p blockers 44 44 88 (44.0%)

Age (yr) 44 52 Calcium antagonists 37 50 87 (43.5%)

Range 24-50 36-60 Diuretics 17 34 51 (25.6%)

Coronary arteries Long-acting nitroglycerins 15 33 48 (24.0%)

Narrowed 2 50% in diameter (any) 61% 49% Digitalis preparations 5 13 18 (9.0%)

It 14% 13% Antiarrhythmics 4 8 12 (6.0%)

2 15% 15% Thyroid medications 2 8 10 (5.0%)

3 31% 23% Other hormones 0 10 10 (5.0%)

Previous myocardial infarction 24% 26% Anticoagulants 0 9 9 (4.5%)

Positive Rose questionaire 4 1% 40% Corticosterords 2 3 5 (2.5%)

Stroke 2% 5% Oral contraceptives 0 1 1 (0.5%)

H/O hypertension 45% 54% Cholesterol-lowerrng agents 0 0 0 (0.0%)

Drabetes mellitus 8% 17%

Ever smoked crgarettes 76% 59%

Current cigarette smokers 20% 24%

levels of total and HDL cholesterols,triglyceride, apoB

‘Questionawe data available from 97 men and 103 women.

tin 8 ang~ograms, coronary atherosclerosis was present. but not all vessels were and apoA-1 were similar (p >O.lO) between subjects

completely vlsualtzed.

H/O = hIstory of. receiving and not receiving any 1 of thesemedications.**

Association of lipid-related variables with prema-

ture coronary atherosclerosis: For men, the plasma lev-

Statistical analyses: Univariate distributions of all els of total cholesterol, triglyceride, apoB in plasma and

variables were examined, and all outliers confirmed. d > 1.006 g/ml infranate, and apoA-1 were significant

The associationof lipid and other risk factors with CAD univariate discriminators of CAD (Table III). However,

was studied using logistic regressionfor men and wom- after adjusting for age, only the triglyceride and apoA- 1

en separately, and for the entire study population. Be- levels remained significant predictors of CAD in men

causepatients with CAD were older than those without (Table III). The results in women differed from those in

CAD, measures of association were adjusted for age. men. First, before adjustment for age, the plasma levels

The age-adjustedp value and the correlation coefficient of total, VLDL, and total HDL and HDLs cholesterols,

for each risk factor were calculated from a logistic re- triglyceride, and apoB in whole plasma and in d > 1.006

gression model with CAD as the dependent variable, and >1.019 g/ml infranates, and apoA-2 were all sig-

and age and the risk factor of interest as the indepen- nificantly associatedwith CAD (Table III). Adjustment

dent variables. All continuous variables were divided for age removedonly total HDL cholesterol and plasma

into quartiles and examined as categorical variables. apoA-2 as significant indicators of premature CAD in

The results of the continuous and categorical analyses women. The ratio of plasma apoB to apoA-1 was signif-

were similar. Therefore, only the continuous models are icantly associatedwith premature CAD in both men

presented. and women (Table III). Lp(a) levels were higher in

Multivariate logistic regression models were con- those with than in those without CAD, but did not

structed by considering all the variables that were asso- reach statistical significance.

ciated with CAD after adjustment for age only. Odds Becausethe levels of apoB were clearly stronger in-

ratios for continuous variables were calculated for a 1 dicators of CAD in women than in men, whereas the

SD difference in the variable. This allows for compari- level of apoA-1 was stronger in men, the distributions of

son of the strength of associationof CAD with different plasma levels of these apolipoproteins were examined.

variables. For men, the plasma apoB levels were shifted toward

higher values in those with CAD (Figure l), whereasin

RESULTS women, the distribution of plasma apoB levels in those

Characteristics of study population: The character- with CAD appearedbimodal (Figure 1). The distribu-

istics of the study population are summarized in Table tion of plasma apoA-1 levels was shifted toward lower

I. A higher proportion of men than women had prema- values in men with CAD; in contrast, the distributions

ture and more severe (3-vessel) CAD, but these differ- of apoA-1 levels in the women with and without prema-

ences did not reach statistical significance. In subjects ture CAD were much broader and relatively similar

without CAD, the distribution of the most severely af- (Figure 1).

fected segment <50% was as follows: no lesion (70.1%), Multivariate analysis of lipid-related didmhmtors

1 to 20% lesion (17.2%), 21 to 40% lesion (12.6%) and and premature coronary artery disease in men and

41 to 49% lesion (none). History of hypertension and women: Logistic regression models showed that the

diabetes was more prevalent in women than in men. plasma apoB level was more closely associated with

Medication use: The most frequently taken medica- CAD than were total and LDL cholesterols,or apoB in

tions in the previous 2 weeks (in order of use) were: /3 the 1.006 and 1.019 g/ml infranates among men, wom-

blockers, calcium antagonists, diuretics and long-acting en and the total study population. When each of the

nitroglycerines (Table II). The mean differences be- latter variables was modeled simultaneously with plas-

tween subjects with and without CAD in the plasma ma apoB (and age), the association of plasma apoB

PREDICTORS OF PREMATURE CORONARY ATHEROSCLEROSIS 1017

TABLE III Association of Plasma Levels (mg/dl) of Lipids, Lipoprotein Cholesterols and Apolipoproteins with Premature Coronary

Atherosclerosis in Men and Women

Men Women

With Without Age- With Without Age-

CAD CAD Unadjusted Adjusted CAD CAD Unadjusted Adjusted

(n = 60) (n = 39) p Value* p Valuet (n = 51) (n = 53) p Value* p Valuet

Age (yrs) 45.8 41.5 0.0001~ - 53.9 51.8 0.06 -

Total cholesterol 240 221 0.04 0.30 255 220 0.0007 0.002

VLDL cholesterol 53 45 0.20 0.69 55 37 0.005 0.007

IDLcholesterol 16 15 0.69 0.74 18 13 0.18 0.31

LDL cholesterol 127 119 0.35 0.68 135 119 0.09 0.07

HDL cholesterol 46 48 0.60 0.57 51 58 0.03 0.06

HDLz cholesterol 17 16 0.68 0.84 21 24 0.27 0.35

HDL3 cholesterol 31 33 0.28 0.23 31 36 0.03 0.03

Triglycerides 208 143 0.0004 0.006 202 128 0.009 0.014

Plasma apoB 153 135 0.01 0.13 159 126 0.0001 0.0003

ApoB > 1.006 g/ml 135 119 0.02 0.13 139 110 0.0004 0.0016

ApoB > 1.019 g/ml 127 119 0.31 0.66 135 110 0.003 0.007

Plasma apoA-1 131 147 0.02 0.02 147 163 0.07 0.09

Plasma apoA-2 28 28 0.69 0.93 27 28 0.04 0.07

Lp(a) 19 15 0.43 0.29 19 12 0.07 0.09

Plasma apoB/apoA-1 1.23 0.97 0.002 0.02 1.17 0.82 0.0001 0.0001

WnadJusted p value from Student’s t test.

tAdjusted for age only in logisbc regression model.

$p values ~0.05 level are underlined.

§Triglyceride values were log transformed for 2 reasons. First, they were markedly skewed toward high values (p < 0.01). Second, log triglyceride was more strongly associated with

CAD, indlcatlng that log transformabon allowed for better description of its association with CAD. Values reported are antIlog of result m log scale.

Thefollowlngmeasurementswere not performed in Indicated numberofsamples: VLDL (n = l), IDL (n = 21, LDL(n = 3), HDL (n = 11, HDLz (n = 17), HDL, (n = 16). plasma

apoB (n = 3),.apoB I” d > 1.006 g/ml (n = l), apoB in d > 1.019 g/ml (n = 3), apeA- (n = 11, apoA-2 (n = 361, Lp(a) (n = 31) and apoB/apoA-1 (n = 4).

Apo = apollpoproteln; CAD = coronary artery disease; HDL = high-density lipoprotein; IDL = Intermediate-densaty lipoprotein; LDL = low-density Ilpoproteln; Lp (a) = kpoprotein

(a); VLDL = very low density lipoprotein.

Apolipoprotein B Level (mgldl) in Men Apolipoprotein Al Level (mgldl) in Men

*opw-v

Apolipoprotein B Level (mgldl) in Women Apolipoprotein Al Level (mgldl) in Women

FIGURE 1. The disfriion of plasma levefs of wns B (left) and A-l (right) in men (fop) and women (boffom) with

(/J/a& bars) and without (cfod-hfcfld liars) comnary artery drease (CAD).

1018 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CARDIOLOGY VOLUME 69 APRIL 15, 1992

r TABLE V

1

r I

TABLE IV Multivariate Comparison of Plasma Levels of Lipids, Association of Nonlipid Risk Factors with Premature

Lipoprotein, Cholesterol and Apolipoproteins as Predictors of Coronary Atherosclerosis in Men and Women

Premature Coronary Atherosclerosis in Men and Women

Men Women

Men Women (n = 97) (n = 103)

(n = 98) (n = 101)

With Without p With Without

Vanable r Value p Value* r Value p Value* CAD CAD Value* CAD CAD p Value*

Age 0.236 0.002 0.000 0.24 H/O hypertension 51% 37% 0.39 62% 47% 0.15

Tnglyceridet 0.190 0.009 0.064 0.11 Diabetes 15% 3% 0.20 27% 8% 0.03

Plasma apoB 0.000 0.258 0.195 0.007 Ever smoked 88% 58% 0.005 82% 38% 0.0001

Plasma apoA-1 -0.150 0.026 0.000 0.29 Fasting blood 101 90 0.36 109 99 0.39

sugar (mg/dl)

‘pvalues co.05 are underlined.

tTr@yceride values were log transformed. Body mass Index 28 28 0.74 26 26 0.83

Correlation coefficient(r) is from multiple logistic regresw3n. (kg/m2)

ape = apolipoprotein

I I

Family history of

CAD before

age 60 yearst

Father 29% 28% 0.74 22% 24% 0.83

with CAD was stronger, and the association between Mother 5% 13% 0.17 15% 18% 0.83

the other risk factor and CAD was weak and not sta- Either parent 28% 34% 0.28 33% 37% 0.82

tistically significant. The only exception to this state- Both parents 2% 6% 0.62 4% 2% 0.81

ment was that among men, plasma apoB and apoB in *Age-adjusted p value from a logistic regrew%; values ~0.05 are underlined.

tFamlly hlstory of CAD, defmed as myocardial infarction (fatal or nonfatal) or anglna

the 1.006 g/ml infranate were equally associatedwith pectons.

The folIowIng measures were not performed I” the lndlcated number: fasting blood

CAD. Similarly, the log of plasma triglyceride was sugarh = 5) and family hlstoty (n = 25).

more closely associated with CAD than was plasma CAD = coronary artery disease: H/O = history of.

VLDL, log of plasma VLDL or plasma triglyceride lev-

els before log transformation. ApoA-1 was more closely

associatedwith CAD in men, women and the total sam- premenopausal.Menopausal status could not be deter-

ple than were HDL and HDL2 cholesterols. However, mined for 24 women (23%) who had hysterectomies.

HDLj cholesterol was more closely associated with Plasma apoB level was higher in the 36 postmenopausal

CAD than was apoA-1 among women (p = 0.08 and women with CAD than in the 25 without CAD (156 vs

0.53, respectively, when HDLj and ApoA-1 were mod- 132 mg/dl; p = 0.03). Among premenopausalwomen,

eled simultaneously with age). The significance of this this difference was even more striking (mean plasma

finding is uncertain, particularly becauseneither apoA- apoB level 184 mg/dl in those with (n = 3) vs 114

1 nor HDL3 were associatedwith CAD in women after mg/dl in those without (n = 16) CAD; p = 0.01). Thus,

adjustment for plasma apoB level. For men, age, log plasma apoB level was associatedwith CAD in both

triglyceride and apoA-1 levels were independently asso- pre- and postmenopausalwomen, and the association

ciated with CAD, whereas the additional contribution may be stronger for premenopausalones.

of plasma apoB level was not statistically significant Association of nonlipid risk factors with premature

(Table IV). In women, plasma apoB level was the best We next determined whether

coronary artery disease:

nonlipid risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes,

indicator for CAD. Log triglyceride was mildly associ-

ated and apoA-1 levels were only weakly associated smoking, family history of premature myocardial in-

with CAD after adjustment for apoB level (Table IV).farction, and so forth were significantly associatedwith

Menopausal status and plasma apolipoprotein B premature CAD (Table V). Using univariate analysis,

levels in women: Sixty-one women (59%) in the study history of ever smoking was strongly and significantly

were postmenopausal, whereas eighteen (17%) were associatedwith premature CAD in both men and wom-

TABLE VI Multiple Logistic Regression Models of Lipid- and Nonlipid-Related Risk Factors as Predictors of Premature Coronary

Atherosclerosis in Men and Women I

All Men Women

(n = 196) (n = 96)* (n = lOO)*

Variable OR 95% Cl p Valuet OR 95% Cl p Valuet OR 95% Cl p Valuet

Age (10 yrs) 2.7 1.3 5.5 0.007 8.4 1.9 36.9 0.01 1.8 0.7 4.2 0.2

Smoking (ever) 5.0 2.3 10.7 0.001 3.3 1.0 11.1 0.05 6.0 2.2 16.6 0.001

Triglyceride (0.3 logsIS 1.7 1.1 2.7 0.011 2.4 1.1 5.2 0.02 1.5 0.9 2.6 0.13

ApoB (40 mg/dl) 1.6 1.1 2.4 0.016 1.4 0.8 2.6 0.27 1.7 1.0 2.9 0.04

ApoA-1 (40 mg/dl) 0.8 0.5 1.1 0.16 0.5 0.3 1.0 0.05 0.9 0.6 1.4 0.60

Sex (men) 2.3 0.9 5.8 0.08

*Three men and 4 women were not Included due to m,ss,ng data.

tp values co.05 are underllned.

tTrlglyceride levels were log transformed.

APO = apollpoproteln; Cl = confidence Interval: OR = odds ratio.

PREDICTORS OF PREMATURE CORONARY ATHEROSCLEROSIS 1019

en. The other variables did not differ significantly be- high level of triglyceride were the best indicators of

tween men with and without CAD (p >0.05). In wom- CAD. The significantly lower level of apoA-1 in men

en (but not in men) history of diabetes reached statisti- with premature CAD was clearly not accompaniedby a

cal significance (Table V). lower level of HDL cholesterol (or its subfractions). In a

Considefatien ef the strangest lipid- and nonfipid- previous angiographic study,r3 we also found that plas-

relatarI varIaMer simuttaneourly: Using multiple logis- ma total HDL cholesterol did not significantly predict

tic regressionmodels,plasma levels of apoB and apoA- 1 the presenceof l-, 2- or 3-vesselCAD in men aged 30

were better predictors of CAD than was LDL or HDL to 49 years, but did so in those aged 50 to 70.13More

cholesterol (and subfractions) for the entire study popu- recently, Heam et al2 similarly found that older men

lation (Table VI). Total cholesterol level was not a pre- (mean age 57 years) with CAD had lower HDL choles-

dictor of CAD after adjustment for the plasma apoB terol levels. In agreement with our previous report of

levels, but triglyceride level remained a significant indi- another cohort, plasma levels of total HDL cholesterol

cator of premature CAD. Smoking and age were in women with premature CAD was significantly lower

strong, nonlipid predictors (Table VI). For men, triglyc- than in those without CAD.21 In the present study, this

eride level followed by apoA-1 were the best lipid-relat- observation was expanded to include levels of HDL3

ed predictors, whereasfor women, plasma apoB was the cholesterol and apoA-1, which were also lower in wom-

best independent lipid predictor (Table VI). Ever smok- en with premature CAD.

ing remained a strong, independent predictor of prema- Hypertension, diabetes and cigarette smoking were

ture CAD in both men and women. more prevalent in those with than without premature

CAD in both men and women (Table V). However, cig-

DlSClSSlON arette smoking emerged as the strongest nonlipid risk

There are few, if any, previous studies of a compara- factor. The magnitude of the associationbetweensmok-

ble number of women with premature CAD. The plas- ing and CAD was comparable to the strongest lipid-

ma apoB level was the strongestindicator of premature related risk factors. After considering the influence of

CAD in these women. Data from prospective studies triglyceride, apoB and apoA- 1 levels,smoking remained

indicated that total cholesterol level was clearly an im- independently associatedwith premature CAD. The in-

portant predictor of CAD among women as well as ability of somestudies1,2,5to find such a significant con-

men, whereas the association of LDL cholesterol level tribution of smoking to CAD may be related to the size

with CAD in women was lessclear.23Our findings were or nature of the control groups, or to not using ever

consistent with these studies. An increased number of smoking instead of current smoking.

small, dense LDL particles (hyperapoB)24is often ac- We are unable to explain why there was so little ap-

companied by increasedlevels of VLDL cholesterol and parent difference betweenthose with and without CAD

triglyceride. Plasma apoB seems even higher in pre- in regard to family history of premature CAD. How-

menopausalwomen with CAD, indicating the influence ever, not all studies found such an association.28Such

of an endogenous(perhaps genetic) factor on apoB lev- discrepanciesmay be related to patient selection (e.g.,

els that was not obviated (or prevented) by the presence using family history as a criterion for angiography), the

of female hormones. Campos et a125found that post- high prevalenceof CAD in American society, or other

menopausalwomen had significantly smaller LDL-par- biases.28

title size than did premenopausalones, but such differ- We found Lp(a) levels to be higher in those with

ences were not associated with significant changes in than without CAD. However, unlike previous re-

apoB levels. Interestingly, in a study of black men and p~rts,~~i~this trend did not reach statistical significance.

women catheterized for chest pain and an abnormal These differencesdo not appear to be due to our youn-

stress test, Ford et a126found that plasma apoB levels ger population, becauseDahlen et allo found that Lp(a)

were more strongly associated with CAD in women was a better predictor in younger (aged <55 years)

than men. In an older (mean age 60 years) group of 37 than older men. We did find (data not presented)a sub-

women, Sedlis et al3 found that only triglyceride and group of caseswith premature CAD and normal lipo-

apoB levels correlated with severity of CAD. Reardon protein profiles who had increased Lp(a) levels.

et al* reported that CAD in women was related to tri-

Adunwledgement: We thank StephenAchuff, MD,

glyceride, cholesterol and apoB concentrations in IDL.

and Jorge Trejo, MD, for reading the coronary arterio-

The bimodal distribution of plasma apoB levels in grams. The assistanceof Teresa Cloey, BS, Lorraine

women with premature CAD suggestsstrongly the in- Donovan, BS, and the staff of the lipoprotein analytical

fluence of a major gene. Further family studies in the

relatives of these index casesshould elucidate this hy- laboratory is gratefully acknowledged.We thank Brian

McCrindle, MD, for performing the plasma apoA-II

pothesisand determine more precisely the etiologic het- measurements,and Pauline Gugliotta for help with pre-

erogeneity of genetic factors (such as the contribution of

the genesfor hyperapo and familial combined hyperlipi- paring the manuscript.

demia).27

The dyslipidemic pattern in men with premature

CAD generally differed from that in women. First, age REFERENCES

adjustment removed much of the associationof plasma 1. Pearson TA. Coronary arteriography in the study of the epidemiology of

apoB with CAD in men; a low level of apoA- 1, and a coronary artery disease. Epidemiol Rev 19846: 140-166.

1020 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CARDIOLOGY VOLUME 69 APRIL 15, 1992

2. Hearn JA, DeMario Jr SJ, Roubin GS, Hammanstrom M, Sqoutas D. Predic- Artery Disease, Counsel on Cardiovascular Surgery, American Heart Associa-

tive value of lipoprotein (a) and other serum lipoproteins in the angiographic tion Circulation 1975;51(suppl):5-40.

diagnosis of coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 1990;66: I 176- 1180. 15. Kwiterovich PO Jr, White S, Forte T, Bachorik PS, Smith H, Sniderman A.

3. Sedlis SP, Schechtman KB, Ludbrook PA, Sobel BE, Schonfeld G. Plasma Hyperapobetalipoproteinemia in a kindred with familial combined hyperlipide-

apoproteins and the severity of coronary artery disease. Circulation 198673: mia and familial hypercholcsterolemia. Arteriosclerosis 1987;7:21 l-225.

978-986. 16. Bachorik PS, Albers JJ. Precipitation methods for quantification of lipoprc-

4. Genest JJ, McNamara JR, Salem DW, Wilson PWF, Schaefer EJ, Malinow teins. In Albers JJ, Segrest JP. Eds. Methods of Enzymology. Orlando, FL:

MR. Plasma homocyst(e)ine levels in men with premature coronary artery dis- Academic Press, 1986;129(8):78-100.

ease. J Am Co11 Cardiol 1990;16:lI14-1119. 17. Have1 RJ, Eder HA, Bragdon JH. The distribution and chemical composition

5. Schmidt SB, Wasserman AG, Muesing RA, Schlesselman SE, LaRosa JC, of ultracentrifugally separated lipoproteins in human serum. J C/in Imest

Ross AM. Lipoprotein and apolipoprotein levels in angiographically defined cow 1955;34:1345-1353.

nary atherosclerosis, Am J Cardiol 1985;55:1459-1463. 16. Silberman SR, Armentrout MA, Vella FA, Saha AL. MACRA”” Lp(a) for

6. Kottke BA, Zimsmeister AR, Holmes DR Jr, Kneller RW, Hollaway BJ, Mao quantitation of human lipoprotein (a) by enzyme linked immunoassay (abstr).

SQ. Apolipoproteins and coronary artery disease. Mayo C/in Proc 198661: Clin Chem 1990;36:961.

313-320. 19. Lipid Research Clinics Program: Reference Manual for Lipid Research

7. Luria MH, Erel J, Sapoznikov D, Gotsman MS. Cardiovascular risk factor Clinics Prevalence Study. Unpublished protocol. Chapel Hill, NC: University of

clustering and ratio of total cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in North Carolina, Central Patient Registry and Coordinating Centers, 1972.

angiographically documented coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 1991;67: 20. Rose G, McCartnery P, Reid DP. Self-administration of a questionnaire on

31-36. cheat pain and intermittent claudication. Br Med J 1977;31:42-48.

6. Reardon MF, Nestel PJ, Craig IH, Harper RW. Lipoprotein predictors of the 21. Prout TE. Diabetes mellitus, In: Harvey AM, ed. Principles and Practice of

severity of coronary artery disease in men and women. Circulation 1985;71: Medicine. Old Tappan, NJ: Appleton-Century-Croft, 1980;795-815.

881-888. 22. Hunninghake DB. Effects of celiprolol and other antihypertensive agents on

9. Steiner G, Schwartz L, Shumak S, Poapst M. The association of increased serum lipids and lipoproteins. Am Heart J 1991;121:696-701.

levels of intermediate-density lipoproteins with smoking and with coronary artery 23. Bush T, Fried LP, Barrett-Connor E. Cholesterol, lipoproteins and coronary

disease. Circulation 1987;75:124-130. heart disease in women. C/in Chew 1988;34:860-870.

10. Dahlen GH, Guyton JR, Attar, Moham AD, Farner JA, Kautz JA, Gotto 24. Kwiterovich PO Jr. HyperapoB: a pleiotropic phenotype characterized by

AM Jr. Association of levels of lipoprotein Lp(a), plasma lipids, and other lipopro- dense low density lipoproteins and associated with coronary artery disease. Cfin

teins with coronary artery disease documented by angiography. Circularion Chem 1988;33:871-877.

1986;74:758-765. 25. Campos H, McNamara JR, Wilson PUF, Ordovas JM, Schaefer EJ. Differ-

Il. Wilson PWF, Castelli WP, Kannel WB. Coronary risk prediction in adults ences in low density lipoprotein subfractions and apolipoproteins in premenopaus-

(the Framington Heart Study). Am J Cardiol 1987;5991G-94G. al and postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1988;67:30-35.

12. Pearson TA. Risk factors for arteriographically defined coronary artery 26. Ford ES, Cooper CS, Simmons B, Castaner A. Serum lipids, lipoproteins and

disease (PhD dissertation). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and apolipoproteins in black patients with angiographically detined coronary artery

Public Health, Department of Epidemiology, 1983. disease. J C/in Epidemiol 1990;43:625-432.

13. Pearson TA, Bulkley BH, Achuff SC, Kwiterovich PO, Gordis L. The 27. Kwiterovich PO Jr, Motevalli M, Miller M, Bachorik PS, Kafonek SD,

association of low levels of HDL cholesterol and arteriographically defined coro- Chatterjee S, Beaty T, Virgil D. Further insights into the pathophysiology of

nary artery disease. Am J Epidemiol 1979;109:285-295. hyperapobetalipoproteinemia: role of basic proteins I, II, III. Chin Chem

14. Austen WG, Edward JE, Frye RC, Gemini GC, Gott VL, Griffith CCS, 1991;37:317-326.

Goon DC, Murphy ML, Rowe BB. A reporting system on patients evaluated for 26. Becker D, Kwiterovich PO Jr. Coronary prone families: the clinical impor-

coronary artery disease. Report of the Adhoc Committee for Grading of Coronary tance of family history. Cardiovascular Reviews 1988;9:63-71.

PREDICTORS OF PREMATURE CORONARY ATHEROSCLEROSIS 1021

You might also like

- Cholesterol Efflux Capacity, High-Density Lipoprotein Function, and AtherosclerosisDocument9 pagesCholesterol Efflux Capacity, High-Density Lipoprotein Function, and AtherosclerosisMaria Fernanda CoralNo ratings yet

- Prognostic Value of Increased Soluble Thrornbornodulin and Increased Soluble E-Selectin in Ischaernic Heart DiseaseDocument6 pagesPrognostic Value of Increased Soluble Thrornbornodulin and Increased Soluble E-Selectin in Ischaernic Heart DiseaseIoanna Bianca HNo ratings yet

- 2021 Special Care in Dentistry Detection of Calcified AtheromasDocument6 pages2021 Special Care in Dentistry Detection of Calcified AtheromasNATALIA SILVA ANDRADENo ratings yet

- Mond Illo 2011Document11 pagesMond Illo 2011Triệu Khánh VinhNo ratings yet

- Circulation 2011 Mendivil 2065 72Document18 pagesCirculation 2011 Mendivil 2065 72Luis Eduardo Soto GuardoNo ratings yet

- Cholesterol Efflux Capacity, High-Density Lipoprotein Function, and AtherosclerosisDocument9 pagesCholesterol Efflux Capacity, High-Density Lipoprotein Function, and AtherosclerosisReza HariansyahNo ratings yet

- AnatolJCardiol 15 8 640 647Document8 pagesAnatolJCardiol 15 8 640 647Pangestu DhikaNo ratings yet

- 8931 26614 2 PB PDFDocument7 pages8931 26614 2 PB PDFMaferNo ratings yet

- Go 2006Document12 pagesGo 2006my accountNo ratings yet

- Jcu 17 127 PDFDocument8 pagesJcu 17 127 PDFRezkyFYNo ratings yet

- Cardiacinvolve InthDocument7 pagesCardiacinvolve InthsamNo ratings yet

- Swapnil Thesis PaperDocument5 pagesSwapnil Thesis PaperSwapnil SahuNo ratings yet

- Cardiac ValveDocument9 pagesCardiac Valveikbal rambalinoNo ratings yet

- 2359 4802 Ijcs 34 05 s01 0012.x98175Document10 pages2359 4802 Ijcs 34 05 s01 0012.x98175Suryati HusinNo ratings yet

- Hypothyroidism and Atherosclerosis: Anne R. Cappola Paul W. LadensonDocument7 pagesHypothyroidism and Atherosclerosis: Anne R. Cappola Paul W. LadensonLock ThecodeNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Ventricular Arrhythmia and Its Associated Factors in Nondialyzed Chronic Kidney Disease PatientsDocument8 pagesPrevalence of Ventricular Arrhythmia and Its Associated Factors in Nondialyzed Chronic Kidney Disease Patientsjustin_saneNo ratings yet

- Left Atrial Volume Predicts Cardiovascular EventsDocument6 pagesLeft Atrial Volume Predicts Cardiovascular EventsWirawan PrabowoNo ratings yet

- Hepatology - 2012 - Fede - Adrenocortical Dysfunction in Liver Disease A Systematic ReviewDocument10 pagesHepatology - 2012 - Fede - Adrenocortical Dysfunction in Liver Disease A Systematic ReviewJelena PaunovicNo ratings yet

- High Prevalence of Subclinical Left Ventricular Dysfunction in Patients With Psoriatic ArthritisDocument8 pagesHigh Prevalence of Subclinical Left Ventricular Dysfunction in Patients With Psoriatic ArthritisEmanuel NavarreteNo ratings yet

- 23 Preventive Heart Disease, Dyslipidemia and HTNDocument13 pages23 Preventive Heart Disease, Dyslipidemia and HTNVictor PazNo ratings yet

- Evacetrapib y Resultados Cardiovasculares en La Enfermedad Vascular de Alto RiesgoDocument10 pagesEvacetrapib y Resultados Cardiovasculares en La Enfermedad Vascular de Alto RiesgoAlan Villegas SorianoNo ratings yet

- Stroke 1998 Davis 1333 40Document9 pagesStroke 1998 Davis 1333 40ari_julian94No ratings yet

- LDL C Does Not Cause Cardiovascular Disease A Comprehensive Review of The Current LiteratureDocument13 pagesLDL C Does Not Cause Cardiovascular Disease A Comprehensive Review of The Current Literaturenunusan2012No ratings yet

- Endothelial Dysfunction, Biomarkers of Renal Function SCDDocument7 pagesEndothelial Dysfunction, Biomarkers of Renal Function SCDAnonymous 9QxPDpNo ratings yet

- Left Atrial Expansion Index Predicts All-Cause Mortality and Heart Failure Admissions in DyspnoeaDocument8 pagesLeft Atrial Expansion Index Predicts All-Cause Mortality and Heart Failure Admissions in DyspnoeaMathew McCarthyNo ratings yet

- Coronary Slow FlowDocument7 pagesCoronary Slow FlowradiomedicNo ratings yet

- Estudio CORES, Fósforo y MortalidadDocument10 pagesEstudio CORES, Fósforo y MortalidadIris NanayaNo ratings yet

- 469 FullDocument7 pages469 FullCristina Adriana PopaNo ratings yet

- Peripheral Artery Disease: Clinical PracticeDocument11 pagesPeripheral Artery Disease: Clinical Practiceapi-311409998No ratings yet

- Evaluationandmanagement Ofprimary Hyperaldosteronism: Frances T. Lee,, Dina ElarajDocument15 pagesEvaluationandmanagement Ofprimary Hyperaldosteronism: Frances T. Lee,, Dina ElarajDiego BallesterosNo ratings yet

- Atherogenic Dyslipidemia in Patients With Established Coronary Artery DiseaseDocument6 pagesAtherogenic Dyslipidemia in Patients With Established Coronary Artery DiseasebilahalvirayuNo ratings yet

- Efeito Tratamento Hormonal No HDL Nos Trans (Exemplo de Resultados Esperados e Materiais e MétodosDocument10 pagesEfeito Tratamento Hormonal No HDL Nos Trans (Exemplo de Resultados Esperados e Materiais e MétodosHigor FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Hairy Cell Leukemia: A N Unusual Lymphoproliferative DiseaseDocument11 pagesHairy Cell Leukemia: A N Unusual Lymphoproliferative DiseaseMotasem Sirag Mohmmed othmanNo ratings yet

- Anemia in Adults With Congenital Heart Disease Relates To Adverse OutcomeDocument8 pagesAnemia in Adults With Congenital Heart Disease Relates To Adverse OutcomemuhammadrikiNo ratings yet

- Low Systemic Vascular ResistanceDocument7 pagesLow Systemic Vascular ResistanceMuhammad BadrushshalihNo ratings yet

- Aldosterone Does Not Predict Cardiovascular Events Following Acute Coronary Syndrome in Patients Initially Without Heart FailureDocument8 pagesAldosterone Does Not Predict Cardiovascular Events Following Acute Coronary Syndrome in Patients Initially Without Heart FailureAbdulkafi tashaniNo ratings yet

- Autosomal Recessive Hypercholesterolemia: Case ReportDocument7 pagesAutosomal Recessive Hypercholesterolemia: Case ReportLADY DIANEE SOTOMAYOR GUTIERREZNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia in CardiacDocument8 pagesSchizophrenia in CardiacValentina RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Association Between Serum Lipids and Survival in Hemodialysis Patients and Impact of RaceDocument11 pagesAssociation Between Serum Lipids and Survival in Hemodialysis Patients and Impact of RaceJuanCarlosGonzalezNo ratings yet

- HDL Muy Alto 2019Document10 pagesHDL Muy Alto 2019Luis C Ribon VNo ratings yet

- LMA Asociación Con Alteraciones Ecocardiograficas Antes de QuimioterapiaDocument8 pagesLMA Asociación Con Alteraciones Ecocardiograficas Antes de QuimioterapiaMarco Antonio Viera ArevaloNo ratings yet

- Nejmoa 2215025Document11 pagesNejmoa 2215025pharmaNo ratings yet

- CardioDocument10 pagesCardiobursy_esNo ratings yet

- Effects of Anacetrapib in Patients With Atherosclerotic Vascular DiseaseDocument11 pagesEffects of Anacetrapib in Patients With Atherosclerotic Vascular DiseaseCirca NewsNo ratings yet

- ILN Biomarker 2016Document6 pagesILN Biomarker 2016AlienNo ratings yet

- Barter (2007) HDL Cholesterol, Very Low Levels of LDLDocument10 pagesBarter (2007) HDL Cholesterol, Very Low Levels of LDLBruno TeixeiraNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia For Combined Heart and Liver TransplantationDocument12 pagesAnesthesia For Combined Heart and Liver TransplantationFabio MeloNo ratings yet

- Premature Coronary Artery Disease Among Angiographically Proven Atherosclerotic Coronary Artery Disease in North East of Peninsular MalaysiaDocument10 pagesPremature Coronary Artery Disease Among Angiographically Proven Atherosclerotic Coronary Artery Disease in North East of Peninsular MalaysiaLili YaacobNo ratings yet

- Shahid HabibDocument5 pagesShahid HabibHyder ali YahyaNo ratings yet

- Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Risk of Intracerebral HemorrhageDocument14 pagesLow-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Risk of Intracerebral HemorrhageaghniajolandaNo ratings yet

- Dissert. AnisimovDocument7 pagesDissert. AnisimovcamiloNo ratings yet

- PE and CHFDocument9 pagesPE and CHFKu Li ChengNo ratings yet

- Remnant Cholesterol As A Causal Risk Factor For Ischemic Heart DiseaseDocument10 pagesRemnant Cholesterol As A Causal Risk Factor For Ischemic Heart DiseaseIonuț CozmaNo ratings yet

- Pr2 Chapter 1 3 Peta Icamina 2Document21 pagesPr2 Chapter 1 3 Peta Icamina 2JOHN ICAMINANo ratings yet

- The Perindopril in Elderly PeopleDocument8 pagesThe Perindopril in Elderly PeopleluchititaNo ratings yet

- Diabetes MellitusDocument7 pagesDiabetes MellitusAssyifa AnindyaNo ratings yet

- Long Ter OutcomeDocument7 pagesLong Ter OutcomeTeodor BicaNo ratings yet

- Abstracts / Atherosclerosis 252 (2016) E1 Ee196 E185Document2 pagesAbstracts / Atherosclerosis 252 (2016) E1 Ee196 E185MaulNo ratings yet

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 4: VascularFrom EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 4: VascularNo ratings yet

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 16: HematologyFrom EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 16: HematologyNo ratings yet

- United States Patent 5,278,189: Rath Et Al. Jan. 11, 1994Document17 pagesUnited States Patent 5,278,189: Rath Et Al. Jan. 11, 1994longaitiNo ratings yet

- Lipid MetabolismDocument33 pagesLipid MetabolismDharmveer SharmaNo ratings yet

- Reagents Brochure LT314 MAR20Document80 pagesReagents Brochure LT314 MAR20Yousra ZeidanNo ratings yet

- LipoproteinsDocument30 pagesLipoproteinsApurba PradhanNo ratings yet

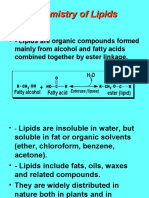

- Chemistry of LipidsDocument88 pagesChemistry of LipidsDanielle Anne Zamora-Matillosa LambanNo ratings yet

- Lipid Profile in AnemiaDocument132 pagesLipid Profile in AnemiaBharath PadmashaliNo ratings yet

- MD - Medical Devices-7Document232 pagesMD - Medical Devices-7qvc.regulatory 2No ratings yet

- Unit 5 TransDocument11 pagesUnit 5 TransGrace FernandoNo ratings yet

- ESC - Prevention of CVDDocument78 pagesESC - Prevention of CVDIrsalina Nur ShabrinaNo ratings yet

- Animal Fat Bact To TableDocument25 pagesAnimal Fat Bact To Tablelokesh tiwariNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology Dyslipidemia PDFDocument9 pagesPathophysiology Dyslipidemia PDFtiffa07110% (1)

- 341 FullDocument13 pages341 FullDrevNo ratings yet

- Accepted Manuscript: Epilepsy ResearchDocument14 pagesAccepted Manuscript: Epilepsy ResearchSyedNo ratings yet

- 2016 ESC/EAS Guidelines For The Management of DyslipidaemiasDocument72 pages2016 ESC/EAS Guidelines For The Management of DyslipidaemiasStăncescu OvidiuNo ratings yet

- Journal Medicinus April 2021Document80 pagesJournal Medicinus April 2021Yuliastuti RahayuNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0169409X20301034 Main PDFDocument30 pages1 s2.0 S0169409X20301034 Main PDFChrispinus LinggaNo ratings yet

- BiochimieDocument3 pagesBiochimieCDM achiffaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1933287417304403 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S1933287417304403 MainSalvador GoveaNo ratings yet

- Dyslipidemia 2021Document86 pagesDyslipidemia 2021Rania ThiniNo ratings yet

- Bandeali-Farmer2012 Article High-DensityLipoproteinAndAtheDocument7 pagesBandeali-Farmer2012 Article High-DensityLipoproteinAndAtheDainius JakubauskasNo ratings yet

- Randox Monaco RX BrochureDocument16 pagesRandox Monaco RX BrochureIslam BiomyNo ratings yet

- S51 - Home Collection Bhubaneswar LAB Purabi, Plot No.2084/8437Near Bhubaneswar Municipality Corporation, Vivekananda Ma BhubaneshwarDocument15 pagesS51 - Home Collection Bhubaneswar LAB Purabi, Plot No.2084/8437Near Bhubaneswar Municipality Corporation, Vivekananda Ma Bhubaneshwarjitu_behera45No ratings yet

- PR-02964-vitros Assay Menu Disease state-NADocument4 pagesPR-02964-vitros Assay Menu Disease state-NAchinuswamiNo ratings yet

- (Rath & Pauling) - Heart Disease Part Two by Jeffrey Dach MDDocument22 pages(Rath & Pauling) - Heart Disease Part Two by Jeffrey Dach MDpedpixNo ratings yet

- Egg Yolk Proteins Gels and EmulsionsDocument6 pagesEgg Yolk Proteins Gels and EmulsionsGeesurihani Ibrahim IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Al., 2008. American Heart Association American Stroke AssociationDocument6 pagesAl., 2008. American Heart Association American Stroke AssociationPuput mopanggaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Chemistry Notes (Blanked) - ABI PDFDocument34 pagesClinical Chemistry Notes (Blanked) - ABI PDFAnya IgnacioNo ratings yet

- High Yield Biochemistry PDFDocument41 pagesHigh Yield Biochemistry PDFKyle Broflovski100% (2)

- Biochemistry Lipids MCQDocument10 pagesBiochemistry Lipids MCQBeda Malecdan67% (6)

- Pharmacotherapy of Dyslipidemia by DR SarmaDocument123 pagesPharmacotherapy of Dyslipidemia by DR Sarmamae2003No ratings yet