Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fa

Fa

Uploaded by

Priyanka George0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

3 views3 pagesAccountants use generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) to prepare Financial statements. These principles have been developed by the accounting profession and the SEC. There are other, more technical standards accountants must Iollow when preparing Iinancial statements.

Original Description:

Original Title

fa

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentAccountants use generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) to prepare Financial statements. These principles have been developed by the accounting profession and the SEC. There are other, more technical standards accountants must Iollow when preparing Iinancial statements.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

3 views3 pagesFa

Fa

Uploaded by

Priyanka GeorgeAccountants use generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) to prepare Financial statements. These principles have been developed by the accounting profession and the SEC. There are other, more technical standards accountants must Iollow when preparing Iinancial statements.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles

Accountants use generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) to guide them in

recording and reporting Iinancial inIormation. GAAP comprises a broad set oI principles

that have been developed by the accounting proIession and the Securities and Exchange

Commission (SEC). Two laws, the Securities Act oI 1933 and the Securities Exchange

Act oI 1934, give the SEC authority to establish reporting and disclosure requirements.

However, the SEC usually operates in an oversight capacity, allowing the FASB and the

Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) to establish these requirements. The

GASB develops accounting standards Ior state and local governments.

The current set oI principles that accountants use rests upon some underlying

assumptions. The basic assumptions and principles presented on the next several pages

are considered GAAP and apply to most Iinancial statements. In addition to these

concepts, there are other, more technical standards accountants must Iollow when

preparing Iinancial statements. Some oI these are discussed later in this book, but other

are leIt Ior more advanced study.

Economic entity assumption. Financial records must be separately maintained Ior each

economic entity. Economic entities include businesses, governments, school districts,

churches, and other social organizations. Although accounting inIormation Irom many

diIIerent entities may be combined Ior Iinancial reporting purposes, every economic

event must be associated with and recorded by a speciIic entity. In addition, business

records must not include the personal assets or liabilities oI the owners.

Monetary unit assumption. An economic entity's accounting records include only

quantiIiable transactions. Certain economic events that aIIect a company, such as hiring a

new chieI executive oIIicer or introducing a new product, cannot be easily quantiIied in

monetary units and, thereIore, do not appear in the company's accounting records.

Furthermore, accounting records must be recorded using a stable currency. Businesses in

the United States usually use U.S. dollars Ior this purpose.

Full disclosure principle. Financial statements normally provide inIormation about a

company's past perIormance. However, pending lawsuits, incomplete transactions, or

other conditions may have imminent and signiIicant eIIects on the company's Iinancial

status. The Iull disclosure principle requires that Iinancial statements include disclosure

oI such inIormation. Footnotes supplement Iinancial statements to convey this

inIormation and to describe the policies the company uses to record and report business

transactions.

Time period assumption. Most businesses exist Ior long periods oI time, so artiIicial

time periods must be used to report the results oI business activity. Depending on the type

oI report, the time period may be a day, a month, a year, or another arbitrary period.

Using artiIicial time periods leads to questions about when certain transactions should be

recorded. For example, how should an accountant report the cost oI equipment expected

to last Iive years? Reporting the entire expense during the year oI purchase might make

the company seem unproIitable that year and unreasonably proIitable in subsequent

years. Once the time period has been established, accountants use GAAP to record and

report that accounting period's transactions.

Accrual basis accounting. In most cases, GAAP requires the use oI accrual basis

accounting rather than cash basis accounting. Accrual basis accounting, which adheres

to the revenue recognition, matching, and cost principles discussed below, captures the

Iinancial aspects oI each economic event in the accounting period in which it occurs,

regardless oI when the cash changes hands. Under cash basis accounting, revenues are

recognized only when the company receives cash or its equivalent, and expenses are

recognized only when the company pays with cash or its equivalent.

Revenue recognition principle. Revenue is earned and recognized upon product

delivery or service completion, without regard to the timing oI cash Ilow. Suppose a store

orders Iive hundred compact discs Irom a wholesaler in March, receives them in April,

and pays Ior them in May. The wholesaler recognizes the sales revenue in April when

delivery occurs, not in March when the deal is struck or in May when the cash is

received. Similarly, iI an attorney receives a $100 retainer Irom a client, the attorney

doesn't recognize the money as revenue until he or she actually perIorms $100 in services

Ior the client.

Matching principle. The costs oI doing business are recorded in the same period as the

revenue they help to generate. Examples oI such costs include the cost oI goods sold,

salaries and commissions earned, insurance premiums, supplies used, and estimates Ior

potential warranty work on the merchandise sold. Consider the wholesaler who delivered

Iive hundred CDs to a store in April. These CDs change Irom an asset (inventory) to an

expense (cost oI goods sold) when the revenue is recognized so that the proIit Irom the

sale can be determined.

Cost principle. Assets are recorded at cost, which equals the value exchanged at the time

oI their acquisition. In the United States, even iI assets such as land or buildings

appreciate in value over time, they are not revalued Ior Iinancial reporting purposes.

Going concern principle. Unless otherwise noted, Iinancial statements are prepared

under the assumption that the company will remain in business indeIinitely. ThereIore,

assets do not need to be sold at Iire-sale values, and debt does not need to be paid oII

beIore maturity. This principle results in the classiIication oI assets and liabilities as

short-term (current) and long-term. Long-term assets are expected to be held Ior more

than one year. Long-term liabilities are not due Ior more than one year.

Relevance, reliability, and consistency. To be useIul, Iinancial inIormation must be

relevant, reliable, and prepared in a consistent manner. Relevant information helps a

decision maker understand a company's past perIormance, present condition, and Iuture

outlook so that inIormed decisions can be made in a timely manner. OI course, the

inIormation needs oI individual users may diIIer, requiring that the inIormation be

presented in diIIerent Iormats. Internal users oIten need more detailed inIormation than

external users, who may need to know only the company's value or its ability to repay

loans. Reliable information is veriIiable and objective. Consistent information is

prepared using the same methods each accounting period, which allows meaningIul

comparisons to be made between diIIerent accounting periods and between the Iinancial

statements oI diIIerent companies that use the same methods.

Principle of conservatism. Accountants must use their judgment to record transactions

that require estimation. The number oI years that equipment will remain productive and

the portion oI accounts receivable that will never be paid are examples oI items that

require estimation. In reporting Iinancial data, accountants Iollow the principle of

conservatism, which requires that the less optimistic estimate be chosen when two

estimates are judged to be equally likely. For example, suppose a manuIacturing

company's Warranty Repair Department has documented a three-percent return rate Ior

product X during the past two years, but the company's Engineering Department insists

this return rate is just a statistical anomaly and less than one percent oI product X will

require service during the coming year. Unless the Engineering Department provides

compelling evidence to support its estimate, the company's accountant must Iollow the

principle oI conservatism and plan Ior a three-percent return rate. Losses and costssuch

as warranty repairsare recorded when they are probable and reasonably estimated.

Gains are recorded when realized.

Materiality principle. Accountants Iollow the materiality principle, which states that

the requirements oI any accounting principle may be ignored when there is no eIIect on

the users oI Iinancial inIormation. Certainly, tracking individual paper clips or pieces oI

paper is immaterial and excessively burdensome to any company's accounting

department. Although there is no deIinitive measure oI materiality, the accountant's

judgment on such matters must be sound. Several thousand dollars may not be material to

an entity such as General Motors, but that same Iigure is quite material to a small, Iamily-

owned business.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Internship Report - EasternDocument101 pagesInternship Report - EasternPriyanka George75% (4)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- MBA-3rd Sem MDU (OCD) PDFDocument88 pagesMBA-3rd Sem MDU (OCD) PDFPriyanka George0% (1)

- Presentationgo: Lorem Ipsum Lorem Ipsum Lorem Ipsum Lorem IpsumDocument3 pagesPresentationgo: Lorem Ipsum Lorem Ipsum Lorem Ipsum Lorem IpsumPriyanka GeorgeNo ratings yet

- What Is AgileDocument4 pagesWhat Is AgilePriyanka GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Data-Driven 3D Cone Chart For Powerpoint: Sample TextDocument2 pagesData-Driven 3D Cone Chart For Powerpoint: Sample TextPriyanka GeorgeNo ratings yet

- What Is A User StoryDocument2 pagesWhat Is A User StoryPriyanka GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Aguinis pm3 Tif 07Document15 pagesAguinis pm3 Tif 07Priyanka GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Scrum: by Ramya PillaiDocument48 pagesScrum: by Ramya PillaiPriyanka GeorgeNo ratings yet

- 07ovarian PathologiesDocument5 pages07ovarian PathologiesPriyanka GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Unit-2 (Two) Human Resource PlanningDocument2 pagesUnit-2 (Two) Human Resource PlanningPriyanka GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Ectopic Gestation: Clinical PresentationDocument5 pagesEvaluation of Ectopic Gestation: Clinical PresentationPriyanka GeorgeNo ratings yet

- 08 PlacentaDocument7 pages08 PlacentaPriyanka GeorgeNo ratings yet

- 4 - FX02 PRINCE2 Sample Practitioner Paper - V1.5Document58 pages4 - FX02 PRINCE2 Sample Practitioner Paper - V1.5Priyanka GeorgeNo ratings yet

- POM Module 2 Quality NotesDocument46 pagesPOM Module 2 Quality NotesPriyanka GeorgeNo ratings yet

- HRM KtuDocument5 pagesHRM KtuPriyanka George100% (1)

- Business QuizDocument54 pagesBusiness QuizPriyanka GeorgeNo ratings yet

- (Books - Stevenson, Buffa, Aswathapa, Adams or Any OM Book) : Production & Operations ManagementDocument20 pages(Books - Stevenson, Buffa, Aswathapa, Adams or Any OM Book) : Production & Operations ManagementPriyanka GeorgeNo ratings yet

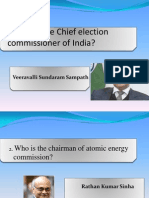

- 1.who Is The Chief Election Commissioner of India?: Veeravalli Sundaram SampathDocument10 pages1.who Is The Chief Election Commissioner of India?: Veeravalli Sundaram SampathPriyanka GeorgeNo ratings yet