Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1-3. "Elders" Were Given Authority in Local

Uploaded by

Nikola Pap0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views3 pagesThis document discusses the authorship, date, nature, and situation addressed in the book of 2 John. It was likely written by John the Apostle around the same time as 1 John, and functions as an official letter from church leaders. The letter addresses the problem of secessionists who held an inadequate view of Christ, compromising with pagan or Jewish views. The secessionists did not view Jesus as the supreme Lord but as a prophet like John the Baptist. The document also provides commentary on the contents of 2 John, explaining the meaning and cultural context of various parts of the letter.

Original Description:

Original Title

2.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document discusses the authorship, date, nature, and situation addressed in the book of 2 John. It was likely written by John the Apostle around the same time as 1 John, and functions as an official letter from church leaders. The letter addresses the problem of secessionists who held an inadequate view of Christ, compromising with pagan or Jewish views. The secessionists did not view Jesus as the supreme Lord but as a prophet like John the Baptist. The document also provides commentary on the contents of 2 John, explaining the meaning and cultural context of various parts of the letter.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views3 pages1-3. "Elders" Were Given Authority in Local

Uploaded by

Nikola PapThis document discusses the authorship, date, nature, and situation addressed in the book of 2 John. It was likely written by John the Apostle around the same time as 1 John, and functions as an official letter from church leaders. The letter addresses the problem of secessionists who held an inadequate view of Christ, compromising with pagan or Jewish views. The secessionists did not view Jesus as the supreme Lord but as a prophet like John the Baptist. The document also provides commentary on the contents of 2 John, explaining the meaning and cultural context of various parts of the letter.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

Authorship, Date.

See the introduction to 1 John and to the Gospel of John; there

is little stylistic difference between 1 and 2 John. Although John himself might send

a shorter personal letter resembling a longer one he had previously written, it is

unlikely that a forger would try to produce such a short document that added so

little to the case found in 1 John. Further, a later forgery of 2 John (or 3 John) would

have drained it of its authority for the audience, since the contents of 2 and 3 John

indicate that the hearers knew the writer personally.

Nature of the Letter. Second John may function as an official letter, the sort that

*high priests could send to Jewish leaders outside Palestine. The length is the same

as that of 3 John; both were probably limited to this length by the single sheet of

papyrus on which they were written. In contrast to most *New Testament letters,

most other ancient letters were of this length.

Situation. Second John addresses the problem of the same secessionists that

1 John addressed. The secessionists’ inadequate view of *Christ was probably either

a compromise with *synagogue pressure (see the introduction to Gospel of John)

or a relativization of Jesus to allow more compromise with paganism (see the introduction

to Revelation)—probably the latter. For the secessionists, Jesus was a great

prophet like John the Baptist and their own leaders, but he was not the supreme

Lord in the flesh (cf. 1 Jn 4:1-6; Rev 2:14, 20). Some propose that they may have been

affiliated with or forerunners of Cerinthus (who distinguished the divine Christ and

the human Jesus, like some modern theologians) or the Docetists (who claimed that

Jesus only seemed to be human). All these compromises helped the false teaching’s

followers better adapt to their culture’s values what remained of Christianity after

their adjustments, but led them away from the truth proclaimed by the eyewitnesses

who had known Jesus firsthand.

Commentaries. See the introduction to 1 John.

1-3. “Elders” were given authority in local

Jewish communities by virtue of their age,

prominence and respectability; age was respected.

John assumes this simple title (cf.

1 Pet 5:1) rather than emphasizing his apostleship

here. The “chosen lady” (nasb, niv) or

spiritual mother could refer to a prophetess/

elder (cf. 3 Jn 4; contrast Rev 2:23). But it more

likely refers to a local congregation here (see v.

13); both Israel and the *church were portrayed

as women.

4-6. The commandment John mentions

here was an old one because it was in the *law

(Lev 19:18), although Jesus’ example gave it

new import (Jn 13:34-35). In the context of 1–2

John, “loving one another” includes cleaving

to the Christian community (rather than

leaving it, as the secessionists were doing).

7-9. See discussion in the introduction.

10. Guests were to be accorded hospitality

and travelers to be put up in hosts’ homes (cf.

3 Jn 5-6; it is possible, though not certain, that

the houses in question here may also be house

churches); early Christian missionaries had

depended on this hospitality from the beginning

(Mt 10:9-14). Traveling philosophers

called sophists charged fees for their teaching,

as some of Paul’s opponents in Corinth

probably did.

But just as Jewish people would not receive

*Samaritans or those they considered impious,

so Christians were to exercise selectivity concerning

whom they would admit. Early

Christian writings (particularly a text of

mainly authoritative traditions known as the

Didache) show that some prophets and

*apostles traveled around, and that not all of

them were true prophets and apostles.

Greetings were an essential part of social protocol

at that time, and the greeting (“Peace be

with you”) was intended as a blessing or prayer

to impart peace.

11. In the *Dead Sea Scrolls, one who provided

for an apostate from the community was

regarded as an apostate sympathizer and was

expelled from the community, as the apostate

was. Housing or blessing a false teacher was

thus seen as collaborating with him.

12. “Paper” is papyrus, made from reeds

and rolled up like a scroll. The pen was a reed

pointed at the end, and the ink was a compound

of charcoal, vegetable gum and water.

Written letters were considered an inferior

substitute for personal presence or for a

speech, and writers sometimes concluded

their letters with the promise to discuss

matters further face-to-face.

13. It was common to send greetings from

those near the sender. For the “sister,” see

1-2. This is a standard greeting in many ancient

letters, which quite often began with a

prayer for the reader’s health, frequently including

the prayer that all would go well with

the person (not just material prosperity, as

some translations could be read as implying).

This greeting might be similar to saying “I

hope you are well” today, but it represents an

actual prayer that all is well with Gaius (see

comment on 1 Thess 3:11). “Gaius” was a

common name.

3-4. Rabbis and philosophers sometimes

spoke of their *disciples as their “children”;

here John probably intends those he brought

to *Christ (cf. Gal 4:19 and perhaps the later

Jewish tradition that when someone made a

convert to Judaism, it was as if the converter

had created the convert).

5-6. Hospitality was a critical issue in the

Greco-Roman world, and Jewish people were

especially concerned to take care of their own.

Most inns also served as brothels, making a

stay there unappealing, but Jewish people

could expect to find hospitality from their

fellow Jews; to prevent abuse of this system,

they normally carried letters of recommendation

from someone the hosts might know to

substantiate their claim to be good Jews. Christians

had likely adopted the same practice.

7-8. Philosophers and sophists (traveling

professional speakers, which is how many

observers in the Greco-Roman world interpreted

traveling Christian preachers) often

made their livings from the crowds to whom

they spoke, although others took fees or

were supported by wealthy *patrons. Like

Jewish people, Christians showed hospitality

to travelers of their own faith, and these traveling

preachers were dependent on this

charity. Jewish people spoke of the sacred

“Name” of God; John is apparently applying

this title to Jesus.

9-11. Diotrephes is apparently leader of another

house church; he refuses to show hospitality

to the missionaries who have letters of

recommendation from the elder. Scholars

have speculated whether the issue was doctrinal

disagreement, disagreement over church

leadership structure or that Diotrephes was

simply outright disagreeable; at any rate, he

refuses to accept the authority of John that

stands behind the missionaries he backs. To

reject a person’s representatives or those recommended

by a person was to disrespect the

person who had written on their behalf.

12. This is the recommendation for Demetrius,

who has not only John’s attestation but

that of the rest of his home church(es). (For

letters of recommendation, see comment on 2

Cor 3:1.) No one in Diotrephes’s house church

will receive him, so Gaius’s house church must

help him.

13-15. Sometimes ancient letters closed as

John does here. Most letter writers employed

*scribes, and if John is writing by hand, he may

well wish to close quickly. See comment on

2 John 12. If “friends” is here a title for a group,

it probably refers to fellow Christians in the

place from which the elder is writing; these

Christians may have borrowed the idea from

the *Epicureans, whose philosophical communities

consisted especially of “friends.”

You might also like

- (And Never Know The Joy) - Sex and The Erotic in English PoetryDocument503 pages(And Never Know The Joy) - Sex and The Erotic in English PoetryEmilio Vicente100% (1)

- The Setting of 2 and 3 JohnDocument12 pagesThe Setting of 2 and 3 JohnJOhn100% (2)

- Jesus, John, and The Essenes - Robert FeatherDocument12 pagesJesus, John, and The Essenes - Robert FeatherChris Schelin100% (2)

- 2 John: Notes OnDocument23 pages2 John: Notes OnchandrasekarNo ratings yet

- The Bible Knowledge Commentary Epistles and ProphecyFrom EverandThe Bible Knowledge Commentary Epistles and ProphecyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- ColossiansDocument62 pagesColossiansRichard WatsonNo ratings yet

- How To Tell If Someone Likes YouDocument48 pagesHow To Tell If Someone Likes YouS- Educte100% (1)

- 2 John 3 John: Notes & OutlinesDocument8 pages2 John 3 John: Notes & OutlinesPaul James BirchallNo ratings yet

- The Canon of ScriptureDocument2 pagesThe Canon of Scripturesilverock0% (1)

- A Dream Within A DreamDocument24 pagesA Dream Within A DreamKenneth Arvin TabiosNo ratings yet

- HebrewsDocument146 pagesHebrewsmarfosd100% (1)

- 1peter Constable PDFDocument122 pages1peter Constable PDFM David RajaNo ratings yet

- The Letters of Paul The Apostle To The GentilesDocument9 pagesThe Letters of Paul The Apostle To The GentilesAfacereNo ratings yet

- ColDocument75 pagesColapi-303640034No ratings yet

- The Randall House Bible Commentary: 1,2,3 John and RevelationFrom EverandThe Randall House Bible Commentary: 1,2,3 John and RevelationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Vendor PO & NPO Invoice Process Through VIM (Vendor Invoice Management) Two Type of Invoice ProcessDocument15 pagesVendor PO & NPO Invoice Process Through VIM (Vendor Invoice Management) Two Type of Invoice Processdivu_dhawan12100% (1)

- Perspectives on Israel and the Church: 4 ViewsFrom EverandPerspectives on Israel and the Church: 4 ViewsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Kalam Hazrat Jami (R.a)Document33 pagesKalam Hazrat Jami (R.a)sheraz121295% (39)

- A Shorter Commentary On Galatians: Don GarlingtonDocument193 pagesA Shorter Commentary On Galatians: Don Garlingtontony_aessd9130100% (1)

- Hebrews: Christ: Perfect Sacrifice, Perfect PriestFrom EverandHebrews: Christ: Perfect Sacrifice, Perfect PriestRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- A Private Commentary on the Bible: ColossiansFrom EverandA Private Commentary on the Bible: ColossiansRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 2 Corinthians and Galatians: A Critical & Exegetical CommentaryFrom Everand2 Corinthians and Galatians: A Critical & Exegetical CommentaryNo ratings yet

- 1503-607-The Historical St. PaulDocument124 pages1503-607-The Historical St. Paulisaacchukwuma124No ratings yet

- Tantric Astrology and Dettatreya Ma Ha TantraDocument6 pagesTantric Astrology and Dettatreya Ma Ha TantraHarisLiviuNo ratings yet

- ColossiansDocument62 pagesColossiansxal22950100% (2)

- Galatian ProblemsDocument11 pagesGalatian ProblemsMasha HubijerNo ratings yet

- Answering The Cessationists' Case Against Continuing Spiritual Gifts - by Jon RuthvenDocument6 pagesAnswering The Cessationists' Case Against Continuing Spiritual Gifts - by Jon Ruthvenclaroblanco100% (1)

- Divorce and Remarriage in the Bible: The Social and Literary ContextFrom EverandDivorce and Remarriage in the Bible: The Social and Literary ContextRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- The Ultimate Commentary On 1 Peter: The Ultimate Commentary CollectionFrom EverandThe Ultimate Commentary On 1 Peter: The Ultimate Commentary CollectionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Priesthood and The Epistle To The Hebrews: Heythrop CollegeDocument12 pagesPriesthood and The Epistle To The Hebrews: Heythrop CollegeNilsonMarianoFilhoNo ratings yet

- Exegetical Process Notebook - Greek ExegesisDocument35 pagesExegetical Process Notebook - Greek Exegesisapi-371347720No ratings yet

- Equip Org 2 John 10Document11 pagesEquip Org 2 John 10Luke HanscomNo ratings yet

- 3 John: Notes OnDocument22 pages3 John: Notes OnNjono SlametNo ratings yet

- (9783110596717 - Wisdom Poured Out Like Water) 30. What Did The Author of Acts Know About Pre-70 JudaismDocument13 pages(9783110596717 - Wisdom Poured Out Like Water) 30. What Did The Author of Acts Know About Pre-70 JudaismLester L. GrabbeNo ratings yet

- G 2 in Jerusalem (2:1-10)Document1 pageG 2 in Jerusalem (2:1-10)Anatoly DyatlovNo ratings yet

- Tadros Yacoub Malaty - A Patristic Commentary On JamesDocument73 pagesTadros Yacoub Malaty - A Patristic Commentary On JamesdreamzilverNo ratings yet

- 1 PeterDocument125 pages1 PeterHilberto SchaurichNo ratings yet

- EBSCO FullText 2024 04 02Document8 pagesEBSCO FullText 2024 04 02info.ottawakpcNo ratings yet

- Gospel and Culture - From Didache To OrigenDocument8 pagesGospel and Culture - From Didache To OrigenJoão Lucas LucchettaNo ratings yet

- I Peter AuthorDocument7 pagesI Peter AuthorCHRISHIRL SANTOSNo ratings yet

- What God Is Up ToDocument16 pagesWhat God Is Up ToBagga MartinNo ratings yet

- 1 PeterDocument78 pages1 Peterxal22950No ratings yet

- Notes On: Dr. Thomas L. ConstableDocument45 pagesNotes On: Dr. Thomas L. ConstableR SamuelNo ratings yet

- Social Science and the Christian Scriptures, Volume 3: Sociological Introductions and New TranslationFrom EverandSocial Science and the Christian Scriptures, Volume 3: Sociological Introductions and New TranslationNo ratings yet

- Conflict and Community in The JohannineDocument15 pagesConflict and Community in The JohannineSofi TameneNo ratings yet

- General Epistles - FremontDocument107 pagesGeneral Epistles - FremontzmuseNo ratings yet

- Nti 6 Religious-Background DraneDocument9 pagesNti 6 Religious-Background DraneGianluca Giauro NutiNo ratings yet

- Dining Out On The SabbathDocument16 pagesDining Out On The SabbathBranislav Benny KovacNo ratings yet

- The Letter of JudeDocument5 pagesThe Letter of JudeLinu LalNo ratings yet

- Divinity of Jesus in Early Christian ThoughtsDocument7 pagesDivinity of Jesus in Early Christian ThoughtsL. B. Christian M.P. MediaNo ratings yet

- 1 2 ReyesDocument13 pages1 2 ReyesCarlos MontielNo ratings yet

- Manual for Sojourners: A Study on Peter’s Use of Scripture and Its Relevance TodayFrom EverandManual for Sojourners: A Study on Peter’s Use of Scripture and Its Relevance TodayNo ratings yet

- 2009 Stenschke Mission-1PeterDocument21 pages2009 Stenschke Mission-1Peterm1295rojasNo ratings yet

- NT Holcomb ActsDocument5 pagesNT Holcomb ActsleongkcNo ratings yet

- Statement of Beliefs of The Continuing Church of God DigitalDocument34 pagesStatement of Beliefs of The Continuing Church of God DigitalelcalechNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Analysis of The Apostle Paul's Pre-Conversion and Post-Conversion Approach To Church Discipline Stephen HatfieldDocument8 pagesA Comparative Analysis of The Apostle Paul's Pre-Conversion and Post-Conversion Approach To Church Discipline Stephen HatfieldAfacereNo ratings yet

- General Epistles IDocument4 pagesGeneral Epistles Imaria_meNo ratings yet

- 1 - 3 PillarDocument3 pages1 - 3 PillarLucas GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- Problems-5 Bruce PDFDocument11 pagesProblems-5 Bruce PDFjongorri8261No ratings yet

- Commentary On 1 CorithianDocument4 pagesCommentary On 1 Corithianstefa74No ratings yet

- MaxParallel For SQL Server Best Practices GuideDocument3 pagesMaxParallel For SQL Server Best Practices GuideTechypyNo ratings yet

- Ibn Abi Dunya and Yaqin - LibrandeDocument39 pagesIbn Abi Dunya and Yaqin - LibrandeAbul HasanNo ratings yet

- Embedded Lab Experiment ProgramDocument30 pagesEmbedded Lab Experiment ProgramYash JoshiNo ratings yet

- Strategy Bank - Memory For LearningDocument2 pagesStrategy Bank - Memory For Learningapi-305212728No ratings yet

- Tutorial-4 (Lseek)Document7 pagesTutorial-4 (Lseek)Aditya MittalNo ratings yet

- LAUFER - Christian Art in China.1910Document24 pagesLAUFER - Christian Art in China.1910karlkatzeNo ratings yet

- Pedagogical Implications of The Lexical ApproachDocument16 pagesPedagogical Implications of The Lexical Approachnfish1046No ratings yet

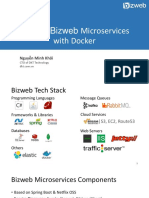

- Building Bizweb Microservices with Docker: Nguyễn Minh KhôiDocument25 pagesBuilding Bizweb Microservices with Docker: Nguyễn Minh KhôinguoinhenvnNo ratings yet

- Sample Song LineupDocument1 pageSample Song LineupGerald GetaladoNo ratings yet

- Cat Forklift v155b Spare Parts ManualDocument23 pagesCat Forklift v155b Spare Parts Manualjacquelinerodriguez060494sdt100% (128)

- A Brief Commentary On Dua Jawshan KabeerDocument115 pagesA Brief Commentary On Dua Jawshan KabeerScottie GreenNo ratings yet

- CLASSE FIVE SCHEMES OF WORK 15 DecDocument99 pagesCLASSE FIVE SCHEMES OF WORK 15 Decchimène olle100% (1)

- Steps To Writing A Research Paper For CollegeDocument7 pagesSteps To Writing A Research Paper For Collegeafnhicafcspyjh100% (1)

- An Equivalent Pi Network Model For PDFDocument8 pagesAn Equivalent Pi Network Model For PDFWilson G SpNo ratings yet

- TWS 8.4 Reference GuideDocument627 pagesTWS 8.4 Reference GuideguyBangalore45No ratings yet

- Openssl ManDocument467 pagesOpenssl ManLuis CarlosNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement For George Orwells 1984Document8 pagesThesis Statement For George Orwells 1984amywilliamswilmington100% (2)

- Meaning and Circular Definitions (F. Orilia)Document16 pagesMeaning and Circular Definitions (F. Orilia)Daniel Rojas UNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument8 pagesLesson PlanLex VasquezNo ratings yet

- Subtitle Guide NetflixDocument4 pagesSubtitle Guide NetflixKaterina TierNo ratings yet

- SAP Icons and Their CodesDocument26 pagesSAP Icons and Their CodesAnonymous zzw4hoFvHNNo ratings yet

- Movie Scene FullDocument7 pagesMovie Scene FullChin Yee LooNo ratings yet

- Celebrations: Lesson B Festivals and HolidaysDocument55 pagesCelebrations: Lesson B Festivals and HolidaysAlessa GV.No ratings yet

- UiPath Certified RPA Associate v1.0 - EXAM DescriptionDocument7 pagesUiPath Certified RPA Associate v1.0 - EXAM DescriptionabhaysisodiyaNo ratings yet