Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Orr Else - The Protagonists of The Lathe of Heaven

Uploaded by

JimOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Orr Else - The Protagonists of The Lathe of Heaven

Uploaded by

JimCopyright:

Available Formats

Orr Else?

The Protagonists of LeGuin's "The Lathe of Heaven"

Author(s): Carl D. Malmgren

Source: Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts , 1998, Vol. 9, No. 4 (36), Special Issue: On

Psi Powers (1998), pp. 313-323

Published by: International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43308369

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Fantastic

in the Arts

This content downloaded from

128.114.34.22 on Thu, 14 Dec 2023 15:09:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Orr Else? The Protagonists of

LeGuin's The Lathe of Heaven

Carl D. Malmgren

In her essay "Science Fiction

and Mrs. Brown," the title of which acknowledges the line of

filiation between her fiction and that of Virginia Woolf, Ursula K.

Le Guin speaks of the centrality of character to her notion of science

fiction:

when science fiction uses its limitless range of symbol and meta-

phor novelistically, with the subject at the center, it can show us

who we are, and where we are, and what choices face us, with un-

surpassed clarity, and with a great and troubling beauty. (118)

This interest in character frequently causes her to use the alien en-

counter as the narrative dominant; many of her fictions are built on

the issues and tensions arising when a human Self confronts an alien

Other; this kind of encounter necessarily keeps "the subject at the

center," analyzing who we are, exploring what it means to be hu-

man.1

At the same time, Le Guin has also been interested in

larger social questions and in alternative forms of social organiza-

tion; indeed, in the aftermath of the turbulent '60s, she wrote a num-

ber of short fictions - e. g., "The Ones Who Walk Away from

Ornelas" (1973) and "The New Atlantis" (1975) - that deal philo-

sophically with the idea of utopia, the possibility of a perfect society.

But her most accomplished fictions of that period recognize and

build upon the interplay between Self and Society. The Dispos-

sessed (1974), she tells us in "Science Fiction and Mrs. Brown, " be-

gan with the image of a remarkable man, the physicist Shevek. Her

first attempt to capture him failed miserably, she says, because it di-

vorced him from his social context. This character insisted that he

was a "citizen of Utopia": "in the process of trying to find out who

and what Shevek was, I found out a great deal else, and thought as

hard as I was capable of thinking, about society, about my world,

and about myself" (111, 112). The Dispossessed, subtitled "An Am-

313

This content downloaded from

128.114.34.22 on Thu, 14 Dec 2023 15:09:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Orr Else?

biguous Utopia," is a celeb

the relation between Self a

Another novel from t

the relationship between u

abilities and the society i

(1971), has received scant

tral protagonist, George Or

tively." That is, his drea

change reality. Orr discove

dreams, and therefore brin

tory aunt. George Orr, as

realities into being. Le Gui

nary fantasy- " if only dr

ing fiction foregrounds som

calls attention to the fairy

himself to the "goose that

frequently draws attention

to avail himself of Orr's p

up with a magic word to p

repeats Orr's name three t

tence by Orr gives him a

Haber's schemes: "Before f

rections," the alien says in

summoned, in immediate-

Most important, the nov

nie formula articulated i

"The Fisherman and His W

help from the authorities,

in alternative realities. Wil

Orr' s "psychosis," discover

and tries to use it to rema

tured around the conflict between these two men, both

"world-builders" (Cummins 165) . The basis of that struggle, Haber

points out, is that the two men "don't see reality the same way" (82).

In simple terms, Haber and Orr represent two different kinds of sen-

sibilities, two different ways of looking at the world. Since the

stakes in the novel are high- Haber tries to use Orr's power to

real-ize utopia- LeGuin is clearly examining the extent to which

these two types of mental talents can bring about significant change.

Orr's special power and its inscription within a work that interro-

314

This content downloaded from

128.114.34.22 on Thu, 14 Dec 2023 15:09:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

In the Arts

gates the viability of t

more detailed analysis.

Orr's antagonist,

kind of scientific ap

down-to-earth. For him

lems (67-8). Not at all

tached knowledge, s

learning anything if i

"the greatest good for

and use, both as noun

name suggests a confla

particularly interested

bring about a better w

other to eliminate ov

says "To a better worl

"successful" effective dream in which the two of them have

"solved" the overpopulation problem by inventing a plague which

wiped out six billion people, among them Haber' s entire family

(73)! This dream highlights the awesome and awful nature of Orr's

power at the same time that it reveals the ruthlessness of Haber's

ambition. In the end that ambition consumes Haber, turning him

into a "Mad Scientist with an Infernal Machine" (47). In effect,

LeGuin uses Haber in order to critique a certain kind of applied sci-

ence and to expose the idea of incremental progress as a scientific

fiction.

The machine that Haber uses to control Orr's dreams is

called an Augmenter, and its function indicates the root cause of

Haber's incipient madness. Haber notes that the machine provides

"the brain a means of ie(f-stimulation" (34), and Haber uses it to

manipulate Orr's dreams in such a way as to magnify his own pow-

ers, to aggrandize his self. His entire project is powered by a

deep-seated insecurity rooted in solipsistic fear. In their "therapy"

sessions, Haber keeps repeating George's name, as if to remind

himself that there is somebody else there. Not really "sure that any-

one else exist[s]" (32), Haber can finally only see the projections of

his over-stimulated brain: "he can't see anything except his mind,"

Orr claims, "his ideas of what ought to be" (99). In this way, the

novel suggests that Haber's form of applied science is never disin-

terested, always self-serving, always unbalanced. In the end Haber

becomes his name, an empty "Will-I-Am," a naked "will to power"

315

This content downloaded from

128.114.34.22 on Thu, 14 Dec 2023 15:09:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Orr Eise?

that feeds on itself:

The quality of the will to p

ment is its cancellation. To

with each fulfillment, makin

ther one. The vaster the pow

more. As there was no visib

through Orr's dreams, so th

improve the world. (128)

Haber is twice likened

layers without a center. Or

regard; the passive, diffide

that the active, aggressive

for advice about how to d

Heather Lelache, is drawn

It was more than dignity. In

wood not carved .... Briefly

her most, of that insight, w

person she had ever known,

from the center. (95)

This groundedness invests

recognize evil and to try to

that Haber is not intrinsica

right to play God with m

know what you're doing. A

you're right and your mot

... be in touch." Haber can

touch" ( 150) .2 One critic

he does not recognize in th

to consider him a machine,

can exert pressure on the r

that the scientific approac

machine, a Subject into an

spects the existence and int

Orr rightly notes that

and points out that if ther

particularly objects to bein

48) . Haber counters that

possibility of, even den

Cummins puts it, "Orr wis

wishes to adjust the world t

316

This content downloaded from

128.114.34.22 on Thu, 14 Dec 2023 15:09:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

In the Arts

to change the world; h

improvement: he has

reason to believe that l

ent" (31). Haber daydr

naut, the city, the "w

escaping to a cabin in

the power to effect re

the other dreams of us

Orr's position is cle

world won't change or

hand, articulates a mor

he points out that life

that perfect stillness r

contrast, Orr seems t

"The world is," he insi

You have to be with

however, Orr realizes t

own hands, " in order

will, he enters the mae

to the control panel of

In a sense, then, th

humanist Orr triumph

artist" opposes and def

Orr's victory is, howev

of the novel is "radica

tered by the ruin of H

entirely account for t

LeGuin notes in an inte

gloomy and nightmari

One thing I've noticed ab

thing I really don't want

it in Portland. The Lat

among the saddest thin

hopeful, and they're bo

for this. (Cited in Cum

Part of the pessimism

change (itself perhaps a

ity prevalent in the ea

or nullifies the megalo

reacts; he starts nothi

317

This content downloaded from

128.114.34.22 on Thu, 14 Dec 2023 15:09:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Orr Else?

point, noting that Orr scor

cal and intelligence tests, H

"Mr. Either/Or": "Where

you're in the middle; whe

point. You cancel out so tho

(134). Haber's skewered r

sults does have a certain

within the novel's macropl

Actually, turning off

major act of negation and

first occurred four years e

dream effectively. At t

ine-ridden world careened i

tinction of the human race

Orr involuntarily made us

an effective dream that era

world to an uneasy equilibr

four years later, Orr shrink

Heather upbraids him: "Y

anything you weren't supp

think you are! There's noth

isn't supposed to happen.

nist here restates forcefull

results in passivity and ina

nothing that needs to be d

out).

But the 1998 dream and its aftermath are disturbing in

other ways. As Heather points out, Orr only did what had to be

done; the alternative was total extinction. But this heroic effort is

also the event that disrupted his equipoise and drove him to the

drug-taking which landed him in Dr. Haber's care in the first place:

"Four years ago this month, four years ago in April, something had

happened that had made him lose that balance altogether for a while"

(139). Clearly, the novel's attitude toward Orr's mental ability, like

Orr's own attitude toward it, is ambivalent. At first reading, the

novel seems to celebrate the power to dream. It consistently con-

trasts the bedrock sanity of the dreamer Orr with the incipient insan-

ity of the dream-user Haber. The narrative begins with an epigraph

from Chuang Tse about dreams, followed by one of Orr's dreams in

which the ocean, mother of life, is figured as the dream-state. Haber

318

This content downloaded from

128.114.34.22 on Thu, 14 Dec 2023 15:09:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

In the Arts

reminds Orr that hum

mans begin to halluci

that everything dream

form, of being, is the

have argued that in th

lems-pollution, over

Haber: "one source for restoration of balance is in dreams"

(Cummins 159) ; "this call to the powers of dream asserts that there

is no solution but in something which goes beyond rationality and in-

dividual will" (Klein 93).

Orr's comment about the play of form brings to mind an

equivalence that plays at the edge of the reader's consciousness: the

dreamer is the artist. The novel sometimes makes this reading ex-

plicit. Orr's true vocation lies in "design, the realization of proper

and fitting shape and form for things" (123). Orr's brain-pattern

when he dreams effectively is found to resemble that of artists when

they are caught up in the act of creation (63). In this context, certain

comments about Orr's power take on a metaliterary resonance: Orr

taunts Haber by suggesting that there might be other effective

dreamers out in the "real world," working their magic on the fabric

of reality (71); Haber from time to time asks Orr why he didn't

"dream up" something different. In fact, the nature of Orr's dreams

indicates the kind of artist he is. When asked to dream a world with-

out war, he invents the Aliens from Aldebaran and puts them on the

Moon. When asked to get rid of the Aliens, he dreams an Alien in-

vasion of Earth. Orr's imagination, and therefore his art, are

haunted by motifs drawn from science fiction. 3 This idea is rein-

forced by the similarity of his name to that of another 20th-century

artist, the man who dreamt up a distinguished anti-utopic SF novel,

George Orwell.

It should be noted, however, that the novel in which Orr

appears is itself not "pure" science fiction. Science fiction is

grounded in the discourse of science, and Orr's power is itself

counterscientific- it violates the norms of scientific possibility.

Bucknall notes that Orr "has a capacity that is magical rather than

scientific- his dreams come true. This is a proverbial expression

for realizing one's fondest wishes, and yet it is felt by him as a curse

rather than a blessing" (83). Elsewhere, I have defined science fan-

tasy as a hybridized subgenre depicting a world characterized by

319

This content downloaded from

128.114.34.22 on Thu, 14 Dec 2023 15:09:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Orr Else?

"the reversal of natural law or the contravention of the scientific

epistemology"; one form of science fantasy involves the introduc-

tion of a being with counternatural or supernatural powers into a

world otherwise conforming to the dictates of scientific discourse

and scientific necessity (Worlds Apart 139, 150) . Orr represents just

such a being, and he inhabits a regular (rule-centered) sci-

ence-fictional world. His power is extremely counterscientific; Orr

himself admits that what he is doing is totally impossible (35). Most

of Orr' s "magic," it should be noted, is "explained" by the novel's

discourse. Haber, for example, goes to some lengths to account for

effective dreaming in scientific terms (151).

Orr's power and his agonistic relation with Haber make

the novel a very good example of metaficdonal science fantasy. The

struggle between Haber and Orr acts out the conflict between sci-

ence and fantasy that structures this subgenre. Science fantasy is a

generic hybrid, conflating features from fantasy and science fiction,

negotiating the thematic space between them. In simple terms, we

can say that fantasy deals with the real and the unreal, science fiction

with the known and the unknown, and that science fantasy mediates

the two interests, bringing epistemologica! questions to bear on on-

tological issues. It asks, What is real, what unreal, and how do we

know this for sure? This is certainly the case with The Lathe of

Heaven. When George tells Heather that he dreamt their world into

existence back in 1998, he undermines the basic ontology of their

world: "This isn't real. This world isn't even probable," he con-

fesses to her. "We are all dead, and we spoiled the world before we

died. There is nothing left. Nothing but dreams" (105). Orr here

indicates the most disturbing fictional "reality": the fact that the real

world he and Heather share, so material for them, is itself a

"dream." Of course Orr is right- his world is unreal- and this

knowledge resonates metaliterarily in the reader's mind: to be only

a fiction, the function of someone's outrageous dream!4

For the most part Orr, acting out his name, evades the

full implications of his knowledge: he denies the reality of his dream

power (e.g., 80) because to accept it would lead to complete onto-

logical insecurity. But at several places the rents in the fabric of re-

ality make themselves felt to the characters. After not seeing Orr for

a couple of days, Heather finds herself going to the wrong office and

running into walls and realizes that Orr has been effectively dream-

ing again; it makes her wonder "what things are changed and

320

This content downloaded from

128.114.34.22 on Thu, 14 Dec 2023 15:09:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

In the Arts

whether anything's re

prey to vertiginous dou

dered, that because he

dream? What if it was?

manity cannot stomach

to readers of The Lathe

fictional reality underm

ity into insubstantialit

after a bad dream.

Susan Wood begins her interpretive summary of the novel as

follows: "George Orr ... loses his intrinsic balance when ... he be-

gins to create worlds. The novel's opening view of an overcrowded,

polluted, rainwashed Portland of April 2002 is depressingly plausi-

ble. Yet it is also Orr's creation" (199). It is also, of course, Le

Guin's creation. The novel calls into question both Orr's mental

abilities and Le Guin's; Orr' s power, Le Guin's power, the novel-

ist's-all are somehow fantastic, out of this world, and therefore

suspect. At one point Orr challenges Haber's basic project: "You're

trying to reach progressive, humanitarian goals with a tool that isn't

suited to the job" (86). Given that Haber represents the "rational,

progressive mind" (Wood 200), the discredited tool would seem to

be reason. Le Guin does link Haber's applied rationality with an un-

healthy will-to-power which daydreams heroics as it imposes its

nightmare vision on the world. But Orr's follow-up question indi-

cates he has a different tool in mind: "Who has humanitarian

dreams?" He thereby indicts dreaming as a will-less activity that

serves an illogic of its own. "Or(r) else" is exactly that- an empty

threat.

This exchange thus calls into question both types of men-

tal abilities. Insofar as these abilities devote themselves to world

construction- Utopian, fictional, or otherwise- they inevitably

serve a desire to play God. Fredric Jameson has said of Utopian lit-

erature that "its deepest vocation is to bring home . . . our constitu-

tional inability to imagine Utopia itself" (153). In its treatment of

Haber and Orr, The Lathe of Heaven acknowledges and highlights

that inability. Jameson goes on, however, to praise the Utopian

achievement of Le Guin's novel: "George Orr cannot dream Utopia;

yet in the very process of exploring the contradictions of that pro-

duction, the narrative gets written, and 'Utopia' is 'produced,' in the

very movement by which we are shown that an 'achieved' Utopia- a

321

This content downloaded from

128.114.34.22 on Thu, 14 Dec 2023 15:09:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Orr Else?

full representation- is a

novel suggests that Utopia

fantasy, something that n

into existence; Utopia is eit

gerous selfishness or mere

Notes

1. For a more systematic treatment of this kind of SF, see Malmgren,

"Self and Other in SF: Alien Encounters." For an analysis of Le Guin's

handling of this motif, see Hull, who claims that Le Guin "has incorpo-

rated wholesale the question of defining humanity as a dominant theme in

her work" (68).

2. Ironically, Haber diagnoses Orr as suffering from "fear of human

contact" (61). Cf. what Le Guin says about touch in "Science Fiction and

Mrs. Brown": "One by one we live, soul by soul. The person, the single per-

son. Community is the best we can hope for, and community for most peo-

ple means touch-, the touch of your hand against the other's hand, the job

done together, the sledge hauled together, the dance danced together, the

child conceived together" (1 16-7). For a critical treatment of this theme in

Le Guin, see Remington.

3. Cf. Orr' s own comments about the Aliens: "it's not surprising that

the Aliens are on my side. In a sense I invented them. I have no idea in

what sense, of course. But they definitely weren't around until I dreamed

they were, until I let them be. So that there is- there always was- a con-

nection between us" (149).

4. The same realization occurs to the characters in another metafictional

science fantasy, Philip K. Dick's The Man in the High Castle (247).

References

Bucknall, Barbara. Ursula K. Le Guin. NY: Frederick Ungar, 1981.

Cummins, Elizabeth. Understanding Ursula K. Le Guin. Columbia: U.

of South Carolina Press, 1990.

Dick, Philip K. The Man in the High Castle. 1962; rpt. NY: Berkley,

1982.

Hull, Keith N. "What Is Human? Ursula Le Guin and Science Fiction's

Great Theme." Modern Fiction Studies 32.1 (1986): 65-74.

Jameson, Fredric. "Progress Versus Utopia; or, Can We Imagine the

Future?" Science-Fiction Studies 9 (1982): 147-58.

322

This content downloaded from

128.114.34.22 on Thu, 14 Dec 2023 15:09:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

In the Arts

Klein, Gerard. "Le Gu

content. " Modern Critical Views : Ursula K. Le Guin. Ed. Harold

Bloom. NY: Chelsea House, 1986. 85-97.

Le Guin, Ursula K. The Lathe of Heaven. 1971; rpt. NY: Avon, 1973.

Night:Essays on Fantasy and Science Fiction. E

NY:G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1979. 101-19.

Malmgren, Carl D. "Self and Other in SF: Alien E

ence-Fiction Studies 20. 1 (March 1993): 15-33.

Indiana UP, 1991.

Remington, Thomas J. "The Other Side of Sufferin

and Metaphor in Le Guin's Science Fiction Nov

Guin. Ed. Joseph D. Olander and Martin Harry

Taplinger, 1979. 153-77.

Wood, Susan. "Discovering Worlds: The Fiction o

Guin." Modern Critical Views : Ursula K. Le Guin. Ed. Harold

Bloom. NY: Chelsea House, 1986. 183-209.

323

This content downloaded from

128.114.34.22 on Thu, 14 Dec 2023 15:09:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Life as a New Hire, Redrawing the Globe, Volume VIIIFrom EverandLife as a New Hire, Redrawing the Globe, Volume VIIIRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- AccurateNaming Archer 1986Document15 pagesAccurateNaming Archer 1986Fernanda HerremanNo ratings yet

- Dragonology The Idea of The Dragon Among The Greek PDFDocument12 pagesDragonology The Idea of The Dragon Among The Greek PDFSebastianNo ratings yet

- Dragonology The Idea of The Dragon Among The Greek PDFDocument12 pagesDragonology The Idea of The Dragon Among The Greek PDFSebastianNo ratings yet

- Dragonology The Idea of The Dragon Among The Greek PDFDocument12 pagesDragonology The Idea of The Dragon Among The Greek PDFSebastianNo ratings yet

- The Trickster MythDocument39 pagesThe Trickster MythLJ100% (1)

- Horror - Style Issues Around Catharsis EssaysDocument8 pagesHorror - Style Issues Around Catharsis EssayscharlenemybeanNo ratings yet

- Cross NewLaboratoryDreams 2012Document20 pagesCross NewLaboratoryDreams 2012jolev0089No ratings yet

- Tiraboschi, J. - On Disgust - A Menippean Interview. Interview With Robert WilsonDocument11 pagesTiraboschi, J. - On Disgust - A Menippean Interview. Interview With Robert WilsonDirección II N1No ratings yet

- St. Augustine's Confessions, Book VII, Chapter 12Document7 pagesSt. Augustine's Confessions, Book VII, Chapter 12Technical PhantomNo ratings yet

- LMC 3202 Final PaperDocument4 pagesLMC 3202 Final PaperT ANo ratings yet

- Weiss, Allen S. - 1986 - Impossible SovereingtyDocument20 pagesWeiss, Allen S. - 1986 - Impossible SovereingtyMatti LipastiNo ratings yet

- Greece Vs Egypt para HumansDocument6 pagesGreece Vs Egypt para Humansjetienne1991No ratings yet

- Divine Epiphanies in HomerDocument28 pagesDivine Epiphanies in HomerAlvah GoldbookNo ratings yet

- Horror and The Maternal in "Beowulf"Document16 pagesHorror and The Maternal in "Beowulf"desmadradorNo ratings yet

- Discourse As ArchitectureDocument9 pagesDiscourse As ArchitectureAnonymous GUswJgDokNo ratings yet

- JP 4Document15 pagesJP 4Cristina PérezNo ratings yet

- TechnoKabbalah-The Performative Language of Magick and The Production of Occult KnowledgeDocument18 pagesTechnoKabbalah-The Performative Language of Magick and The Production of Occult KnowledgeStella Ofis AtzemiNo ratings yet

- TALESDocument15 pagesTALESAlvin PeñalbaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 43.251.89.56 On Mon, 08 Aug 2022 15:57:00 UTCDocument27 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 43.251.89.56 On Mon, 08 Aug 2022 15:57:00 UTCdhiman chakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Horror and Architecture - Ancient Gods, Old Mansions and The UndeadDocument12 pagesHorror and Architecture - Ancient Gods, Old Mansions and The UndeadJacob Leo HartmanNo ratings yet

- Michael Fournier - Gorgias On MagicDocument14 pagesMichael Fournier - Gorgias On MagicGabrielle CavalcanteNo ratings yet

- Ian Hacking HumansAliens 2009Document17 pagesIan Hacking HumansAliens 200922054No ratings yet

- Unquiet Ghosts - The Struggle For Representation in Jean Rhys - S - Wide Sargasso SeaDocument17 pagesUnquiet Ghosts - The Struggle For Representation in Jean Rhys - S - Wide Sargasso SeaFloRenciaNo ratings yet

- 556the Jacob's Ladder in HomerDocument17 pages556the Jacob's Ladder in HomerRodrigoNo ratings yet

- The Noncorpum's and Mankind's Divine HypothesisDocument7 pagesThe Noncorpum's and Mankind's Divine HypothesisSamuel PoirotNo ratings yet

- Monsters ThesisDocument8 pagesMonsters ThesisPaperWritingHelpOnlineReno100% (2)

- BROWN 1983 The Erinyes in The Oresteia Real Life, The Supernatural, and The StageDocument23 pagesBROWN 1983 The Erinyes in The Oresteia Real Life, The Supernatural, and The StageCecilia PerczykNo ratings yet

- The Classical Association of The Middle West and South, Inc. (CAMWS) The Classical JournalDocument3 pagesThe Classical Association of The Middle West and South, Inc. (CAMWS) The Classical JournalKanyNo ratings yet

- Narrative Performance in The Contemporary Monster StoryDocument19 pagesNarrative Performance in The Contemporary Monster StoryMiguel Lozano100% (1)

- Rhrich GermanDevilTales 1970Document16 pagesRhrich GermanDevilTales 1970AranzaNo ratings yet

- Berghahn Books Sartre Studies International: This Content Downloaded From 131.172.36.29 On Wed, 06 Jul 2016 07:03:34 UTCDocument24 pagesBerghahn Books Sartre Studies International: This Content Downloaded From 131.172.36.29 On Wed, 06 Jul 2016 07:03:34 UTCGeorge DeosoNo ratings yet

- Thesis For Creation MythsDocument7 pagesThesis For Creation Mythsamberbutlervirginiabeach100% (2)

- Thesis About Creation MythsDocument7 pagesThesis About Creation Mythsreneedelgadoalbuquerque100% (2)

- Hitler Vs Frabato by Robert Bruce Baird PDFDocument158 pagesHitler Vs Frabato by Robert Bruce Baird PDFKernel Panic100% (2)

- The Egyptian God Seth As A TricksterDocument5 pagesThe Egyptian God Seth As A TricksterBlackspiderjunk100% (2)

- Existential Literature OneilDocument35 pagesExistential Literature OneilWided SassiNo ratings yet

- Yale University PressDocument84 pagesYale University PressKhurram ShehzadNo ratings yet

- Lovecraft 1Document23 pagesLovecraft 1nandan71officialNo ratings yet

- Celebration of SurpriseDocument20 pagesCelebration of SurpriseignNo ratings yet

- Euripides' Use of Myth Author(s) : Robert Eisner Source: Arethusa, Fall 1979, Vol. 12, No. 2 (Fall 1979), Pp. 153-174 Published By: The Johns Hopkins University PressDocument23 pagesEuripides' Use of Myth Author(s) : Robert Eisner Source: Arethusa, Fall 1979, Vol. 12, No. 2 (Fall 1979), Pp. 153-174 Published By: The Johns Hopkins University PressAhlem LOUATINo ratings yet

- Feder SelfhoodLanguageReality 1983Document19 pagesFeder SelfhoodLanguageReality 1983Isra Tahiya Islam (202013007)No ratings yet

- Chapter 01 PDFDocument30 pagesChapter 01 PDFtelemagicoNo ratings yet

- Villalba 1Document12 pagesVillalba 1Omar sarmientoNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary Energizers IDocument7 pagesVocabulary Energizers ISriharsha Madhira33% (3)

- Maecaella Xelline L. Llorente Bsbamm1-1D Review On Westworld in Relation To EthicsDocument9 pagesMaecaella Xelline L. Llorente Bsbamm1-1D Review On Westworld in Relation To EthicsAcua RioNo ratings yet

- Towards A Definition of Science FantasyDocument24 pagesTowards A Definition of Science FantasyAnonEGSNo ratings yet

- Transgressingthe Limits of Consciousness - SkuraDocument21 pagesTransgressingthe Limits of Consciousness - Skuraberistainlm10No ratings yet

- Bonica NaturePaganismHardys 1982Document15 pagesBonica NaturePaganismHardys 1982estrella.huangfuNo ratings yet

- Blindfolded and Backwards Promethean and Bemushroomed Heroism in One Flew OverDocument10 pagesBlindfolded and Backwards Promethean and Bemushroomed Heroism in One Flew Over1 LobotomizerXNo ratings yet

- Zeus Essay ThesisDocument8 pagesZeus Essay ThesisDereck Downing100% (2)

- Mythology Research Paper IdeasDocument8 pagesMythology Research Paper Ideasegvhzwcd100% (1)

- M4 Analytical EssayDocument5 pagesM4 Analytical EssayVicenteNo ratings yet

- Die Neue Sitte, IphigenieDocument15 pagesDie Neue Sitte, IphigenieMatej KostirNo ratings yet

- J ctt1zkjz0m 5Document16 pagesJ ctt1zkjz0m 5DCI WALBRIDGE PARTNERSNo ratings yet

- 10 2307@27742469Document26 pages10 2307@27742469Постум БугаевNo ratings yet

- Pearson, Ansell Deleuze and DemonsDocument35 pagesPearson, Ansell Deleuze and DemonsFabiana PiokerNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 2.44.138.58 On Fri, 25 Jun 2021 14:32:07 UTCDocument16 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 2.44.138.58 On Fri, 25 Jun 2021 14:32:07 UTCOttavia IsolaNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement For PrometheusDocument6 pagesThesis Statement For Prometheusfbzgmpm3100% (2)

- Constitution and IndividuationDocument9 pagesConstitution and IndividuationAntonio CappielloNo ratings yet

- Simondon Collective Individuation and The Subjectivity of DisasterDocument20 pagesSimondon Collective Individuation and The Subjectivity of DisasterJimNo ratings yet

- Luhmann and Systems Theory - Oxford Research EncyclopediaDocument15 pagesLuhmann and Systems Theory - Oxford Research EncyclopediaJimNo ratings yet

- Objet Petit A - Vertigo (1958)Document375 pagesObjet Petit A - Vertigo (1958)JimNo ratings yet

- Weiskel The Romantic SublimeDocument242 pagesWeiskel The Romantic SublimeJimNo ratings yet

- Simondon and The Process of Individuation - Matt BlueminkDocument21 pagesSimondon and The Process of Individuation - Matt BlueminkJimNo ratings yet

- Timothy Morton Ecology Without Nature Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics 2009Document131 pagesTimothy Morton Ecology Without Nature Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics 2009bal_do_ensueos_28717100% (1)

- De Man, Paul - Aesthetic - Ideology - (Phenomenality - and - Materiality - in - Kant)Document21 pagesDe Man, Paul - Aesthetic - Ideology - (Phenomenality - and - Materiality - in - Kant)JimNo ratings yet

- Simondon Collective Individuation and The Subjectivity of DisasterDocument20 pagesSimondon Collective Individuation and The Subjectivity of DisasterJimNo ratings yet

- Answers To Workbook Exercises: Cambridge University Press 2014Document3 pagesAnswers To Workbook Exercises: Cambridge University Press 2014M BNo ratings yet

- PDF - The Irresistible Kisser 2024 - WatermarkDocument31 pagesPDF - The Irresistible Kisser 2024 - WatermarkRazi100% (1)

- The DimensionsDocument3 pagesThe DimensionsWilliam SanjayaNo ratings yet

- Ch05 P24 Build A ModelDocument5 pagesCh05 P24 Build A ModelKatarína HúlekováNo ratings yet

- Nephrology and HypertensionDocument33 pagesNephrology and HypertensionCarlos HernándezNo ratings yet

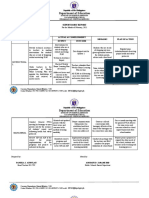

- Department of Education: Supervisory Report School/District: Cacawan High SchoolDocument17 pagesDepartment of Education: Supervisory Report School/District: Cacawan High SchoolMaze JasminNo ratings yet

- Accomplishment and Narrative Report OctDocument4 pagesAccomplishment and Narrative Report OctGillian Bollozos-CabuguasNo ratings yet

- CONCEPT DESIGN ALUM C.W SCHUCO ANDALUSIA Rev01.10.03.222Document118 pagesCONCEPT DESIGN ALUM C.W SCHUCO ANDALUSIA Rev01.10.03.222MoustafaNo ratings yet

- Supplementary: Materials inDocument5 pagesSupplementary: Materials inEvan Siano BautistaNo ratings yet

- First Conditional Advice Interactive WorksheetDocument2 pagesFirst Conditional Advice Interactive WorksheetMurilo BaldanNo ratings yet

- Chap3 Laterally Loaded Deep FoundationDocument46 pagesChap3 Laterally Loaded Deep Foundationtadesse habtieNo ratings yet

- Escalation How Much Is Enough?Document9 pagesEscalation How Much Is Enough?ep8934100% (2)

- Germany: Country NoteDocument68 pagesGermany: Country NoteeltcanNo ratings yet

- Medical Professionalism Across Cultures: A Challenge For Medicine and Medical EducationDocument7 pagesMedical Professionalism Across Cultures: A Challenge For Medicine and Medical EducationYoNo ratings yet

- JournalDocument6 pagesJournalAlyssa AlejandroNo ratings yet

- Law On Intellectual Property TRADEMARK ASSIGNMENTDocument5 pagesLaw On Intellectual Property TRADEMARK ASSIGNMENTCarene Leanne BernardoNo ratings yet

- Calibration Form: This Form Should Be Filled Out and Sent With Your ShipmentDocument1 pageCalibration Form: This Form Should Be Filled Out and Sent With Your ShipmentLanco SANo ratings yet

- Tribune Publishing FilingDocument11 pagesTribune Publishing FilingAnonymous 6f8RIS6No ratings yet

- Mision de Amistad Correspondence, 1986-1988Document9 pagesMision de Amistad Correspondence, 1986-1988david_phsNo ratings yet

- Professional Practice - X Sem - 2017-18 As On 16032018Document89 pagesProfessional Practice - X Sem - 2017-18 As On 16032018harshinireddy mandadiNo ratings yet

- SJAJ ANTICKIH GRKA Keramicke Posude SlikeeDocument563 pagesSJAJ ANTICKIH GRKA Keramicke Posude SlikeeAjdin Arapović100% (1)

- Presentation On Online Car Rental Management System: Presented byDocument41 pagesPresentation On Online Car Rental Management System: Presented byNikhilesh K100% (2)

- Intern CV Pheaktra TiengDocument3 pagesIntern CV Pheaktra TiengTieng PheaktraNo ratings yet

- Bupa Statement To ABCDocument1 pageBupa Statement To ABCABC News OnlineNo ratings yet

- Madeleine Leininger Transcultural NursingDocument5 pagesMadeleine Leininger Transcultural Nursingteabagman100% (1)

- IPPE 1 Community Workbook Class of 2020Document65 pagesIPPE 1 Community Workbook Class of 2020Anonymous hF5zAdvwCCNo ratings yet

- Academic Writing For Publication RELO Jakarta Feb2016 022616 SignatureDocument225 pagesAcademic Writing For Publication RELO Jakarta Feb2016 022616 SignatureNesreen Yusuf100% (1)

- PPSTDocument24 pagesPPSTCrisnelynNo ratings yet

- Point of Sale - Chapter 3Document6 pagesPoint of Sale - Chapter 3Marla Angela M. JavierNo ratings yet

- "Yfa - R : Keyboard Percussion RangesDocument2 pages"Yfa - R : Keyboard Percussion RangesmadroalNo ratings yet

- Who Discovered America?: The Untold History of the Peopling of the AmericasFrom EverandWho Discovered America?: The Untold History of the Peopling of the AmericasNo ratings yet

- To Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceFrom EverandTo Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (51)

- Witness: For the Prosecution of Scott PetersonFrom EverandWitness: For the Prosecution of Scott PetersonRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (44)

- Summary: Lessons in Chemistry: A Novel by Bonnie Garmus: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Lessons in Chemistry: A Novel by Bonnie Garmus: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (8)

- Summary of A Gentleman in Moscow: A Novel by Amor TowlesFrom EverandSummary of A Gentleman in Moscow: A Novel by Amor TowlesRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the HorseFrom EverandThe Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the HorseRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1183)

- Jim Butcher's The Dresden Files: Storm Front Vol. 1From EverandJim Butcher's The Dresden Files: Storm Front Vol. 1Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (8)

- Red Rising: Sons of Ares: Volume 2: Wrath [Dramatized Adaptation]From EverandRed Rising: Sons of Ares: Volume 2: Wrath [Dramatized Adaptation]Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (21)

- The Magic of Reality: How We Know What's Really TrueFrom EverandThe Magic of Reality: How We Know What's Really TrueRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (107)

- Lesbian Zombies From Outer Space: Issue 1From EverandLesbian Zombies From Outer Space: Issue 1Rating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (15)

- Power Born of Dreams: My Story is PalestineFrom EverandPower Born of Dreams: My Story is PalestineRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- Haruki Murakami Manga Stories 1: Super-Frog Saves Tokyo, The Seventh Man, Birthday Girl, Where I'm Likely to Find ItFrom EverandHaruki Murakami Manga Stories 1: Super-Frog Saves Tokyo, The Seventh Man, Birthday Girl, Where I'm Likely to Find ItRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Dirty Little Comics: Volume 1: A Pictorial History of Tijuana Bibles and Underground Adult Comics of the 1920s through the 1950sFrom EverandDirty Little Comics: Volume 1: A Pictorial History of Tijuana Bibles and Underground Adult Comics of the 1920s through the 1950sNo ratings yet

![Red Rising: Sons of Ares: Volume 2: Wrath [Dramatized Adaptation]](https://imgv2-1-f.scribdassets.com/img/audiobook_square_badge/639918345/198x198/2031392476/1699569439?v=1)