Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Omar Saeed ESD Dissertation 2011

Uploaded by

Omar SaeedOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Omar Saeed ESD Dissertation 2011

Uploaded by

Omar SaeedCopyright:

Available Formats

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON: DEVELOPMENT PLANNING UNIT 2010/11

Environmental Justice in the Clean Development Mechanism: A Meta Ethical Policy Analysis

MSc Dissertation

Omar Saeed 9/5/2011

Acknowledgements

A special thanks to Alex Apsan Frediani for helping me to create an acceptable piece of academic writing from a very messy set of ideas. I know it wasnt easy. The next Star is on me.

Abstract

It has been considered previously that environmental policy is often weakened because there are alternative motivations in its construction. Classical policy analysis techniques consider policy problems to be issues of distribution therefore attempting to solve them in this way also. Using an adaption of Schlosbergs (2007) environmental justice, a meta ethical (Frankena, 1988) policy analysis of the discourse and practice of the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) is presented here. Qualitative results are shown for the analysis of CDM discourse through a procedural document and a draft Convention written for the Copenhagen Summit which took place in 2009. The same analysis was carried out for documents relevant to the CDM in practice in the case study context of a hydroelectric dam called Campos Novos in a southern region of Brazil, South America. These have raised two important issues. Firstly, the CDM facilitates instances of inequitable distribution, misrecognition and a lack of participation for stakeholders in the policy process. Secondly, these policy problems are repeated when put into practice in the case of Campos Novos. . The meta ethical (Frankena, 1988) approach to environmental policy analysis indicates that although the CDM may have been created to be a policy that prioritises the environment, this is not reflected in some instances of practices. Further to that, there are indications that national governments of developed countries are using the CDM to their own advantage and plan to continue to do so in the future.

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements................................................................................................................................. 1 Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................... 5 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 1.2 2 Environmental Policy: Major Stages ....................................................................................... 7 The European Union Emissions Trading System: A Brief History.......................................... 11

Theoretical Framework ................................................................................................................. 15 2.1 Environmental Justice ........................................................................................................... 15 Distribution ................................................................................................................... 16 Recognition ................................................................................................................... 17 Participation .................................................................................................................. 18

2.1.1 2.1.2 2.1.3 2.2

Placing the Theory into Context............................................................................................ 19 Added Value of Meta Ethics ....................................................................................... 21

2.2.1 2.3

Brazil: Political Economy ....................................................................................................... 22 Brazil: Hydropower ....................................................................................................... 25 Relevance of Analysis .................................................................................................... 27

2.3.1 2.3.2 2.4 3

Case Study: Campos Novos .................................................................................................. 28

Analysis ......................................................................................................................................... 30

4 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 4 Distribution ........................................................................................................................... 30 Recognition ........................................................................................................................... 32 Participation .......................................................................................................................... 34 Evaluation ............................................................................................................................. 36

Conclusions ................................................................................................................................... 39 4.1 Recommendations ................................................................................................................ 39

5 6

Bibliography .................................................................................................................................. 41 Appendix ....................................................................................................................................... 45 6.1 Breakdown of Modalities and Procedures for Direct Communications with Stakeholders

(UNFCCC, 2011) ................................................................................................................................. 45 6.2 Breakdown of Project Design Document Form (CDM PDD) Version 03.1. (UNFCCC, 2006)

and Validation Report (SGS, 2006) for Hydropower Project at Campos Novos ............................... 47 6.3 Breakdown of the Danish Text (Draft 271109; Decision 1/CP.15) from the Copenhagen

COP15 (2009) .................................................................................................................................... 49

List of Abbreviations

CDM CER CO2 ETS EU ERU FDI GHGs IMF JI MAB NGO PDD PT SBA UN Clean Development Mechanism Certified Emissions Reduction Carbon Dioxide Emissions Trading System European Union Emissions Reduction Unit Foreign Direct Investment Greenhouse Gases International Monetary Fund Joint Implementation Movement for Dam Affected Peoples Non Governmental Organisation Project Design Document Partido dos Trabachadores Standby Arrangement United Nations United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

UNFCCC

1 Introduction

The overall aim of this research is to understand better the role that environmental justice (Schlosberg, 2007) has in the contemporary environmental policy debate. Additionally, the research will be centred on using meta-ethics (Frankena, 1988) in an approach to policy analysis. The aim is to use the approach to identify and understand the key questions about the motivations and discourse that the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) follows and how this affected practice in one of its installations. As part of a meta ethical (Frankena, 1988) policy analysis, it is necessary to study the motivations of the CDM. This is because meta - ethics involves dealing with the establishment and justification of ethical and value judgements (Ibid, 1988). This means taking an anthropological approach to the CDM; peeling back the layers to find out what the real priorities of the policy are. When the original motivations are understood, perhaps it can be better conceived why practices of the CDM are as they currently stand. As part of this approach, it is necessary to document how the major stages of environmental policy have developed to try and clarify the values held in this area. Additionally, an

historical analysis in the context of emissions trading will provide an insight into the construction of the current European Union Emissions Trading System (ETS) and its motivations. Although the CDM is a separate, flexible mechanism of the Kyoto Protocol, the link between the ETS and the CDM has unfolded recently as the latter becomes a way to meet the emissions reduction demands of the former. The analysis and evaluation of these values is contrary to classical policy analysis (Patton and Sawicki, 1993) that tends to deal with policy problems by merely thinking of a speedy solution as opposed to understanding the social and political contexts that may have contributed to the particular issue under examination.

1.1 Environmental Policy: Major Stages

To gain an understanding of where global policy makers perspectives sit in relation to environmental concerns at present, it is worth identifying the key events that have had an effect on this area over the last few decades. This will help contextualize the developing and changing motivations towards environmental policy and provide a first insight into those of the CDM. In 1972, the Limits to Growth, produced by the Club of Rome (a Non - Governmental Organisation (NGO) devoted to addressing world problematique) outlined major trends of policy that were generating concern on the global level. Considered to be most important were the issues of rapid industrialization, the ever increasing population growth, malnutrition as a result of world poverty, environmental damage and the finite nature of non renewable resources. In the same year, the United Nations (UN) Conference on the Human Environment (1972) held in Stockholm, Sweden was the initial stage at which environmental issues entered the realm of international policy. The uptake of the environment as an issue of political interest suggests these concerns were being considered. However, it must be noted that this conference did not produce binding legislation but instead pushed governments to consider the transboundary impacts that pollution can have on neighbouring nations. The motivations here appear to be based more on preventing poor relations between neighbouring states as opposed to environmental concerns. In 1987, the Brundtland Commission on Environment and Development produced the infamous Brundtland Report or Our Common Future. The report made recommendations for improved collaboration between what have become known as the developed and the developing nations, referring to the global north and south respectively. As a result, an action plan for dealing with environmental problems was created which outlined the

8 objectives of the international community in regards to helping reverse trends of exponential growth (Meadows, 2004). The report discussed the issue of sustainable development, indicating that to move towards this concept, governments would need to give ecological concerns similar weighting to economics, tradeand energy (Brundtland Report, 1987). What can be seen here is that even when it was suggested that environmental concerns be given more priority, this could only be perceived if they were on the same level as economic and trade concerns, as though it was impossible for policy makers to imagine anything more. This has been a problem for a number of years and the reverberations of this all too common standpoint are still evident in environmental policy today. The Brundtland Reports (1987) critical development was the consideration of the processes behind implementing institutional and legal change (ibid, 1987) with sustainable development in mind. To echo previous global thinking, the report did not put forward an option to ratify any environmental agreements or legislation that would force nations to make changes. Instead, it recommended increased awareness of polluting practices, improving the mapping of environmental effects on a global scale and using the resources of NGOs and the scientific community to make informed choices (ibid, 1987) that are more sustainable. It is evident that although the environment was beginning to force its way into policy discourse, the policy making itself was not running in conjunction but running as a parallel, with motivations never quite bridging the gap to produce solid environmental legislation. The Rio Earth Summit (1992) took a much more progressive stance on the environment and sustainable development than previous conferences through its key message: Nothing less than a transformation of our attitudes and behaviour would bring about the necessary changes (United Nations, 1992) for a sustainable future.

9 To further support its more progressive nature, there was a large amount of resulting documentation from the event. As legally binding Conventions, the United Nations

Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Convention on Biodiversity were aimed at the prevention of climate change and halting the eradication of biologically diverse species. In addition, Agenda 21 outlined a set of proposals that aimed to address social, economic and ecological problems and strengthen the role of civil society and NGOs in these proposals. However, it was admitted by Maurice Strong, the Conference Secretary General that the overall effect of Agenda 21 was weakened by negotiations by governments (UN, 1992), an indicator that nations wished to carry on in a business as usual format. Taking a meta-ethical (Frankena, 1988) approach to these values, the motivation of government is what needs to be questioned in order to identify the policy problems. It seems the issue is an overemphasis on the economic priorities as opposed to environmental ones. Exactly a decade later (2002), the World Summit on Sustainable Development was held in Johannesburg, South Africa. The outcome from this Summit was a renewed commitment to Agenda 21 and implementation plan for the policy. This indicates the rather stagnant nature of environmental concerns in the political arena and identifies a level of avoidance from government of legally binding commitment to environmental targets. This papers approach to policy analysis will try and identify reasons why there is an apparent reluctance to commit to equitable environmental policy and question the motivations of policy makers to understand what underlying value judgements are preventing equitable progression. So far, the inability to move forward in this respect has been accepted by the powers that be, indicating a total lack of meta ethical (Frankena, 1988) thinking from those who have the strength to impact on the environment we live in. 2009s Summit in Copenhagen did not reach the heights that many people pre-empted it would (Vidal, 2009). Although the USA, China and India all made unconditional pledges to

10 cut or slow the growth of their emissions or find measures to achieve this, at no point was a legally binding agreement created nor was a future date set for doing so. As can be

expected from policy making through a capitalist perspective, details for effects on businesses were also left as very ambiguous, suggesting nations wished to leave room for manoeuvre in relation to their prospects of economic growth. To understand further the motivations behind environmental policy at the time of Copenhagen, the incident of The Danish Text is of great importance. The Danish Text refers to a document created by a transnational group of individuals called, The Circle of Commitment, which is understood to only include members from the developed world. The document proposed that the UN should no longer have control over climate change finance; putting forward the World Bank as the superior financier and it suggested abandoning the Kyoto Protocol entirely. Finally, it looked for political commitment to allow developing countries to emit less than half the emissions of developed ones. It is very plain to see that motivations behind environmental policy are partly being driven by economic factors. The discourse that is developing is one that allows current developed nation behaviours to continue while those countries whose development has been hindered are forced to make drastic cuts. They are also held as financial prisoners by international financial institutions such as the World Bank, having to agree to terms other than their own in order to receive financial aid for climate change adaption. In the case of incidents in environmental policy making such as The Danish Text, meta ethical (Frankena, 1988) questions must be posed to the organisations such as The Circle of Commitment in order to derive why governments feel that this discourse is the correct one to follow. Further to that, it must be understood whether any elements of justice are at play in environmental policy. Why should developing countries cut emissions while

developed ones do not? Why should developing countries be at the mercy of the World Bank while developed ones are not? Why were developing countries prevented from

participating in the development of The Danish Text? Why were they not recognised as

11 important entities in the process? These issues of recognition, participation and distribution are all elements of environmental justice; a key part of the analytical framework which will be discussed in chapter 2.

1.2 The European Union Emissions Trading System: A Brief History

Before the Kyoto Protocol was agreed on in 1997, the EU was relatively apprehensive about constructing an ETS (Skjaerseth and Wettestad, 2009). As might be expected from a supranational body such as the European Union (EU), its members feared that an EU wide ETS would be incompatible with the differing levels of energy consumption and varying economic states that still characterize the EU today. There are a number of reasons as to why the Member States of the EU changed their positions on emissions trading, post Kyoto. Primarily, the ETS Green Paper ( EU, 2000) proposed that such a system could increase cost efficiency in the face of implementing the agreements of Kyoto. Estimates show that Community wide trading by energy producers and energy intensive industry could reduce the costs of implementing the Communitys Kyoto commitments by nearly a fiftha potential cost saving of 1.7 billion a year (ibid, 2000). Additionally, the same paper advocated the potential for a Community wide ETS to address the EUs burden sharing agreement (Article 4, Kyoto Protocol, 1997) through the same economic - efficiency lens, proposing the system as a cost effective way to achieve the required 8% reduction in Greenhouse Gases (GHGs). The Green Paper (2000) also mentions that a high level of autonomy in each States allocation of emissions allowances to the various installations it contains, is a possibility because of different national priorities (ibid, 2000). Consequently, a decentralized system was proposed in order to allow Member States to take charge of the allocation of the allowances to their own installations respectively. This provided a route around the problems of each Member State having different energy economic (Skjaerseth and Wettestad, 2009) requirements.

12 Although it quite reasonably can be argued that the EUs use of the ETS to meet the GHG emission reduction targets of Kyoto was valid, the values of the policy seem to be economic, concerned with the ETS being a cost effective method with which to reduce GHG emissions (Schreurs and Tiberghien, 2007). Once again, the over emphasis on economic motivations, as noted at the Rio Summit in 1992, weakened the environmental benefits of the policy. What forced the EU through the open door of emissions trading, however, was the withdrawal from the Kyoto Agreement by the United States of America in 2001 (Skjaerseth and Wettestad, 2010). This gave the EU a platform on which to present itself as a leader in global environmental policy, not just in idea formulation but also by putting policy into practice (Schreurs and Tiberghien, 2007). Skjaerseth and Wettestad (2010) regard the EU ETS as a mechanism that was put to the top of the pile in order to save Kyoto from failure post US withdrawal. The nature of this decision making suggests that the implementation of the system was not something as meticulously planned as one might think policy would be. It is worth noting that the US withdrawal from Kyoto provided an opportunity for the economist heavy team of the Climate Change Unit at Directorate General Environment to lobby for the implementation of an ETS (ibid, 2009). In 2003, the first phase of the Emissions Trading Directive was adopted and in the following year (key to this research), a Linking Directive was established. This Directive gave EU Member States permission to use the Kyoto Protocols other flexibility mechanisms (the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and Joint Implementation (JI)) in order to meet their ETS GHG reduction targets. Both are explained briefly below.

13

Clean Development Mechanism

Allows a country with an emission-reduction or emissionlimitation commitment under the Kyoto Protocol to implement an emission-reduction project in developing countries Such projects can earn saleable certified emission reduction (CER) credits, each equivalent to one tonne of CO2, which can be counted towards meting Kyoto targets

Joint Implementation

Allows a country with an emission-reduction or emissionlimitation commitment under the Kyoto Protocol to earn emission reduction units (ERUs) from an emission-reduction or emission removal project in another country, each equivalent to one tonne of CO2, which can be counted towards meeting its Kyoto target

The CDM will be explored in greater detail later in this dissertation as it forms a key element of the analysis of the discourse that influences it and the practices that result from it when creating an installation in a developing country. What can be said at this stage of the research is that the establishment of the Linking Directive among the flexible mechanisms identifies an opportunity for Member States to produce a false impression. What is meant by this description is that Member States could deliver fairly modest National Allocation Plans (NAPs) to their industries but allow them to carry on in much the same way they always did. This is because the CDM, for example, allows GHG reduction projects to be set up in developing countries, often rewarding the polluting country with CERs which permit further pollution. This rather incredible paradox is a reoccurring theme that has been noted while examining the development of environmental policy. While a policy might be veiled as environmentally beneficial, beneath is the rather ugly face of the economic motivations that debilitate the potential of environmental policy. During 2005 2008, a pilot phase of the EU ETS was carried out with relatively little success. The perception of the pilot phase is such because the decentralized system that was spoken about earlier in this section became victim to a problem of surplus. The Member

14 State - devised NAPs (of carbon credits) were not stringent or ambitious enough to cut carbon emissions, flooding the market with carbon credits and dropping the price from a high of 30 per tonne to a 2007 low of 0.5 per tonne (Zetterberg et al, 2004; and Grub et al, 2005). Once again, it is obvious that motivations to cut carbon emissions were affected by Member States fear of it affecting business as usual. The ETS was being treated more as a tool to produce economic benefits rather than environmental ones, suggesting a discrepancy between the proposed discourse (of environmental and economic benefits) and practice (simply a redundant market based tool). However, the EU Commission responded strongly to this problem by introducing and receiving full ratification for a proposal for 2013 - 2020 which completely denounced the use of decentralized NAPs and instead will use an EU wide, supra national cap. To further substantiate its commitment to reducing emissions, the Commission will be reducing allowances at a rate of 1.75% per year. What this is expected to achieve is for emissions credits to fetch a higher price because of increased scarcity (Offical Journal of the European Union, 2009). These changes to the system will come into effect in 2013. While this

appears to be a tough stance on the mismanagement and misuse of the ETS, it should not be forgotten that the Linking Directive (at which CER limits remain uncapped) still allows the paradoxical practices mentioned above to take place and this will be analysed in further detail later in this paper.

15

2 Theoretical Framework

2.1 Environmental Justice

In the case of the pending analysis of CDM discourse and practice, the meta ethical (Frankena, 1988) approach that has been suggested as a tool, holds a problem because it has not yet been applied to the context of policy. Therefore, to be applied to policy with any degree of success, there must be criteria to measure much like classical policy analysis (Patton and Sawicki, 1993). Applied to policy, meta ethics (Frankena, 1988) lacks any normative criteria that allow for an analysis to be carried out. This research will be using elements of environmental justice in order to fill the gap that meta ethics (ibid, 1988) leaves in this particular situation. Rather than the traditional, ontological (what we already know) perspective of classical policy analysis (Patton and Sawicki, 1993), applying meta ethics (Frankena, 1988) is concerned with epistemological questions or in other words, what we do not know; attempting to provide more clarification and understanding (ibid, 1988) regarding values held (in this case in policy). Patton and Sawicki (1993) state that the aim of classical policy analysis is to break up the policy problems into their component parts, understand and conceptualize them and hopefully develop new ideas of how to resolve the issues which have been identified, suggesting alternatives to current policy trends as a true policy analyst should (ibid, 1993). A classical policy analysis moves through the motions of asking basic questions to solve policy problems. Here, a problem is identified and evaluated, other policy suggestions are created and put forward and one is selected to be implemented. However, Patton and Sawicki (1993) outline the importance of a policy analyst dealing with a policy problem, to devise their own personal versions (ibid, 1993) of this basic policy analysis process which this framework aims to do.

16 Besides being used for normative criteria, the significance of environmental justice (Schlosberg, 2007) in this research is the way it perceives environmental problems as not being simply distributional. Instead, theorists such as Schlosberg (2007) and Young (1990) advocate the consideration of recognition and participation as elements of distribution. Both theorists suggest looking at the effect of the social context in which these elements occur to avoid treating problems as simply distributional. It should be noted that Schlosbergs (2007) capabilities theory has been omitted from this research and is therefore not discussed in this section. This is because the analysis itself will be avoiding looking at the impacts of the CDM on the capability of people to function (Sen, 1985; Nussbaum, 2000). By no means does this paper doubt the credibility or

question the richness of the capabilities theory but it deems it inappropriate for analysing the discrepancies between CDM discourse and practice.

2.1.1 Distribution

The word justice throws up many different ideas. John Rawls (1971) defined the concept as the appropriate division of social advantages. Looking closer at this quote, one can see that division is a notion of what has been the main body of justice theory (Schlosberg, 2007) in the past i.e. distribution. Although a fantastic concept, Rawls (1971) and Barrys (1995) idea of creating rules for distributive justice while remaining impartial seems a complex notion to achieve. Unable to put it more excellently, the way to impartial rules of justice is to put oneself in an original position (Rawls, 1971) where one does not know the strengths or weaknesses of human society. If reachable, the original position (ibid, 1971) would be the ideal place for the underlying motivations behind environmental policy to be analysed. However, the

complexity of this is that for an analyst, the path towards this position is slightly unclear Using this approach to distribution in the theoretical framework will allow more epistemological questions to be asked in regards to recognition, participation and the social,

17 cultural and political factors that influence them. This provides a way for an analyst to unpack the CDM policy in context, moving back through its construction and asking more meta ethical (1988) questions that classical policy analysis (Patton and Sawicki, 1993) does not.

2.1.2 Recognition

According to its proponents (Fraser, 1997; Honneth, 1995; Young, 1990), recognition is a critical part of the distributive justice mentioned previously. These theorists subscribe to the idea that one must recognise the social context in which an injustice or uneven distribution occurs, criticising distributional theorists that ignore the underlying features of injustice (Schlosberg, 2007). In particular, this is a poignant criterion for analysing the CDM because as analysis will later show, recognition of differences in groups is often overlooked when installations are agreed between parties and when the relevant practices are occurring. Importantly, Young (1990) notes that recognition does not have material limits, meaning that it can not be distributed in the same manner in which (for example) national health care can. This is a critical reason for treating recognition and participation (the next criterion) as being separate from distribution. Frasers (1997) theory of justice links well to this papers approach to policy analysis because it takes a more pluralistic viewpoint of the subject. The approach not only looks at the uneven distribution that people experience but also delves into a deeper mode of analysis. It pushes analysts to clarify how the disrespected identities (Schlosberg, 2007) which lead to misrecognition from the institutional level (which will be a focus of the analysis) have been constructed. Fraser (1997) indicates that justice might be better sought not through simply asking if people are being misrecognised but going that crucial, meta ethical (Frankena, 1988) step

18 further of questioning why the misrecognised have an identity valued in a way that (in the eyes of the misrecogniser) warrants this injustice. Once again, the combination of meta ethics with an environmental justice criterion may provide the platform to analyse the motivations, discourse and practices of the CDM in a way that generates more information about the root causes of injustice in the CDM context. Fraser (1997) also argues that for the problem of misrecognition to be addressed, a structural and institutional critique must be carried out. Therefore, official documents from the political level will be analysed in Chapter 3 in order to try and understand where misrecognition in CDM and environmental policy stems from.

2.1.3 Participation

The justice of participation is an important criterion for this research because of its links to recognition and distribution. For example, through policies such as the CDM, political institutions can create an environment which facilitates inequity and misrecognition (further explanation will take place in the analysis). In turn, the misrecognised suffer from a lack of opportunity to participate in processes that affect them. In the present context, an example might be that a territory is chosen by developers for a CDM installation. This piece of territory houses indigenous people who need consulting regarding the viability of the projects instalment. As is often the case and as the analysis will demonstrate, this

consultation process is often non existent or very limited and is carried out across different scales. To better analyse participation in the next chapter, meta ethics (Frankena, 1988) may contribute to unpacking the continuing cycle of misrecognition noted by Schlosberg (2007): When you are misrecognised, you are unlikely to participate; when you do not participate, you are not recognised. This approach to policy analysis asks questions which demand answers that require consideration of social, cultural and political issues such as the dominant issues of the political economy. One method of attempting to find these answers

19 is by using criteria such as participation in order to understand the drivers of institutionalized domination and oppression (Young, 1990) within these contexts. Critical to this research will be deducing at what scale any participation has taken place within the context of the CDM case study. Instead of accepting at face value that there is relevant civil society participation in the CDM, this approach to policy analysis will instead defragment this assumption further, asking questions regarding the scale of participation and the reasons why participation is split across these scales and occurs in all / only some of the possible scales. As a result, the combination of meta ethics (Frankena, 1988) and

participation might be able to identify issues with participation in CDM policy that classical policy analysis (Patton and Sawicki, 1993) might not do so well.

2.2 Placing the Theory into Context

Prior to this section, what has been explained is the breakdown of the main components of environmental justice theory with the omission of capabilities for reasons stated earlier. This section will identify what the major problem is that needs to be addressed, why it is relevant and then state why using distribution, recognition and participation in a meta ethical (Frankena, 1988) policy analysis may produce interesting results. The problem that must be addressed is as follows. Firstly, while it is assumed that the discourse the CDM follows prioritises the environment, the practices that are part of CDM projects (planning processes and installation) hold an over emphasis on economic motivations as has been documented in environmental policy development (discussed in the first chapter) which results in inequitable distribution, misrecognition and lack of participation from those people affected. The assumption made regarding CDM discourse may be

incorrect but this can only be noted once the analysis is completed. This policy analysis of the CDM project is currently of particular relevance because of the recent EU legislation development in the ETS. The motion passed will allow 20% of Member

20 State emission reduction targets (originally meant to bet met through the ETS) to be met through CDM offset projects in developing countries courtesy of the Linking Directive mentioned in Chapter 1.2. Undoubtedly, this will lead to an increase in CDM installations in different countries around the world. Subsequently, it is necessary to carry out this research in order to draw notice to the discourse and practice of a policy that will have such a large impact on so many people in the developing world. In order to attend to this problem, Frankenas (1988) concept of meta ethics will be used to facilitate espistemological thinking towards the construction of CDM discourse and how this is replicated / not replicated in practice. This approach provides the chance to analyse policy in a different way but in practical application as will be the case in this paper, it seems to be slightly empty. The reference to emptiness is not a criticism of meta ethics (ibid, 1988) itself because it does not seem that policy was ever a target area for the theory as it was purely philosophical (ibid, 1988). Through choosing criteria, it is hoped that this issue can be remedied through this theoretical framework, while providing an in depth methodology to analyse the discourse and practice of the CDM through measuring if the policy values any of these criteria. In classical policy analysis, a set of common measures to evaluate a policy is often used before identifying alternatives. Patton and Sawicki (1993) note this common group of

measures as cost, net benefit, effectiveness, efficiency, equity, administrative ease, legality, and political acceptability. The meta ethical (Frankena, 1988) approach to policy analysis will similarly consider equity but in terms of distribution, recognition and participation in the hope that this will generate more fruitful analysis. The other criteria of classical policy

analysis (Patton and Sawicki, 1993) have been avoided with the aim of not falling into the trap of repeating the status quo. The fact that distribution is a primary and common concern of policy analysts suggests that there is a disconnect in the classical policy analysis (ibid, 1993) process. Specifically,

21 classical policy analysis (ibid, 1993) results in the underlying elements of distribution (recognition and participation) not being addressed because the former is not considered to be constructed in the way some justice theorists (Honneth, 1995; Fraser, 1997, Schlosberg, 2007) feel it should be. This suggests that classical policy process only touches the surface of policy problems through distribution and perhaps creates an environment for any instances of misrecognition and lack of participation for certain groups and individuals to continue.

2.2.1 Added Value of Meta Ethics

To end this section, a table has been constructed giving a brief indication of how meta ethics (Frankena, 1988) might be able to build on typical questions of distribution, recognition and participation in environmental justice in the pending analysis. Criterion Distribution Theory Environmental Justice Meta ethics Are the benefits of the CDM What are the benefits distributed equitably? considered to be by the different parties? Are some benefits not addressed or given less importance? What reasons are there for some benefits of the CDM valued higher than others? How has the context in which misrecognition is occurring in the CDM been constructed? What are the values held by those who constructed the CDM? What drives the values held (if applicable) by misrecognisers that lead them to misrecognise other stakeholders?

Recognition

Are stakeholders being misrecognised in the CDM process at any point? In what context does misrecognition in the CDM occur?

Participation

Are stakeholders allowed to participate in the CDM process?

What judgments regarding stakeholders are being made which results in a lack of

22 participation? Can they participate at all times or is this at scale? What values regarding the benefits of the CDM are being held that make some people believe that it is acceptable to create an instance of inequitable participation?

2.3 Brazil: Political Economy

As part of this meta ethical (Frankena, 1988) policy analysis, it is necessary to assess the political economic context of Brazil. Within classical policy analysis, Patton and Sawicki (1993) note that often the geographic and political context of policy problems are considered too far ranging to allow a standard, efficient way of approaching them in analysis. This consideration is a value judgement and, contrary to this approach, meta ethics (Frankena, 1988) should be void of value judgment. This means that as opposed to classically defining the problem in its current context, the analysis is approached by studying the dominant issues of the political economy in the hope of further clarifying the influence of political forces on policies including the CDM. These details are documented here. After many years of economic mismanagement and feckless governance (Roett, 2010), the then Brazillian Minister of Finance, Henrique Cardoso, produced a stabilization program which aimed to take charge of inflation and prep the country for increased economic growth. The so called Real Plan (1994) was a success not only for Brazil overall but for Cardoso himself. After reinventing the countrys currency name, Cardoso was elected President of Brazil in 1994. Cardosos presidency helped to open up (in terms of trade and foreign direct investment (FDI)) Brazils economy during his two terms, the second of which ended in 2003 when Luiz Incio Lula Da Silva (from here on in - Lula), originally a leftist, trade unionist representative, was elected. Before Lula came to power, between 2001 and 2002, Brazil was hit by an energy crisis for which a number of dry (in terms of climate) years are said to be responsible. In many

23 countries, droughts would not necessarily be as large a problem but in the case of Brazil, the sheer scale of hydroelectric energy generation (80% of electricity supply) was also to blame for the crisis. During this period, the level of management necessary to ensure that constant blackouts were not experienced was high and costly (Roett, 2010). Cardoso established a crisis

management board that he chaired which ensured bonuses (culminating at US$200m) for those whom resided under the newly legalized limit on consumption during this time. It seems that the costs of increased management plus incentives and the risk of the popularity of the government at stake in times of crisis could all be possible catalysts for Brazils increased hydroelectric interests. After all, no long lasting president would risk the repetition of an energy crisis. For the Brazilian people, the election of Lula meant a future which held the promise of 10 million jobs (ibid, 2010) and the redistribution of land. Although there are conflicting views of the true success of Lula and his Partido dos Trabachadores (PT), some progress was made. Seizing an opportunity to flex its muscles, Brazil put an end to its stand by arrangement (SBA) (Roett, 2010) with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). An SBA is an agreed sum of money which is borrowed from the IMF by a country in economic crisis in order to meet its balance of repayments (IMF, 2011). However, SBAs are 100% conditional; repayments are set out on a timescale and interest is accrued accordingly with time taken to repay. When agreeing to borrow from the IMF, Brazil agreed to adjust its economic policies to overcome the problems that led it to seek funding in the first place (Ibid, 2011). This is testament to what Brazils economic strength allowed it to break away from. It is clearly documented that on a macroeconomic scale, Brazil took a very neoliberal approach to its policies in order to produce high levels of economic growth (Luna and Klein, 2006; Arestis and Saad Filho, 2007; Roett, 2010,). Even the leftist origins of Lula and the PT dissipated quickly upon entering government. This was partly to avoid an economic

24 collapse that loomed due to speculation regarding exactly how leftist the PTs policies would be. In fact, Lula was interested in economic growth, centrist policies and pursuing a lively foreign policy; visiting many countries around the globe in order to develop relationships. Policies that would produce financial accumulation were prioritised just as they had been in previous governments. This provides an example of the approach to policy in Brazil. If the PT had stuck to their leftist roots, it would be feasible to think that the environment would be prioritised very highly in policy. However, the move back to the centre is telling of a

government that sees economic growth as a central policy motivation. As a result of increased growth, regional disparities of income and wealth were ignored in the country (Arestis and Saad Filho, 2007) which suggests inequitable distribution among the population. This is further highlighted by employment figures in Brazil that show a

growth in those hired under a formal labour contract meaning the loss of many jobs in the countrys large informal sector (Ibid, 2007) which is evidence to the misrecognition of those working in the informal labour market. Brazils self - sufficiency holds relevance for this paper because the countrys search for growth and its improved control of its own markets have potential to be key reasons why hydropower is favoured in the country. For example, Brazil vigorously defended the position of itself and other developing countries in the realm of climate change mitigation at the 2009 Copenhagen summit (Ibid, 2010; Vidal, 2009). The argument from developing nations was (and still is) that Brazil and other developing nations should not have their path out of poverty halted or hindered by being forced to fix the climate change problems that have been largely attributed to developed nations. Brazil argued that its ethanol and hydroelectricity production are clean (at least from CO2) and therefore it should push forward and help the industries grow.

25

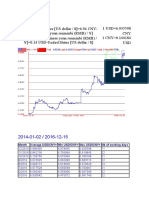

8 % of the world's registered CDM projects are in Brazil

54% of these are focused on renewable energy (hydropower or bioethanol)

195million tonnes of CO2 equivalent reductions in first period of carbon trading (2008 2012)

2.3.1 Brazil: Hydropower

The question that needs to be asked is Why is hydroelectricity so integral to Brazil? Geographically, Brazils natural water resources are plentiful so it would seem totally logical to use the potential of the worlds largest reservoir of fresh water in order to generate electricity, for example. For one, it reduces dependency on finite fossil fuels, placing Brazil in a strong position as energy supplies deplete. At present, renewable energy supply covers half the countrys energy demands and over three quarters of this supply is from hydroelectricity. For Brazil this means relatively low contributions of CO2 on a global scale. However, the potential in the hydropower sector is also an opportunity for other non Brazilian companies to gain CERs by creating CDM projects in the country. Hydropower projects are the most cost effective type of CDM project because ironically they do not cut carbon (the most expensive GHG to mitigate) at least not directly. Obviously, hydropower projects are less carbon intensive but when considered carefully, they are not reducing CO2 in the atmosphere; they are just not making any more. Aware of this opportunity, there is growing interest from private sector investors in CDM projects in developing economies such as Brazil. This stems from suggestions that Brazil,

26 China and India will have to slow the pace of their development in light of post Kyoto agreements in 2012. Subsequently, large, transnational organisations that often work with international banks have financed CDM projects in Brazil in order to receive CERs. The organisation is then able to either use the CERs to cover its own CO 2 emissions or sell them on using the carbon trading system if the organisation holds a surplus. The sheer number of hydropower projects in Brazil that are awaiting CDM approval and that have been accepted is indicative that different entities are aware of and motivated by the likelihood of profit (in CERs) from their installation. CDM hydropower projects (especially dams) have caused a reaction from communities and civil society regarding poor levels of distribution, participation and instances of misrecognition. Documenting these instances have been The Movement for Dam Affected Peoples (MAB) along with a NGO called International Rivers, both of which will appear again later in this paper. The brief analysis of the political economy suggests two things. Firstly, Brazil is a country that wants to grow further in order to become more powerful. The steps towards this goal have been and are policies that increase economic growth and financial accumulation, creating inequitable distributions in wealth and income, misrecognising groups and individuals along the way. Secondly, it seems the Brazilian government might have an understandable fear of being burdened with another energy crisis like that of 2001-2002. Further to that, there is a level of attraction for any country to be self sufficient, especially in the area of energy. This could explain the high number of hydropower projects in the country and particularly the number of validated or pre-validation CDM projects as it can be assumed Brazil would welcome this type of FDI to help the sustainability of its energy.

27

2.3.2 Relevance of Analysis

Following on from the political economic context, it is important to state the significance of the documents that will be examined in the analysis within the Brazilian political economy. The CDM Procedures and Modalities for Direct Communication with Stakeholders, (UNFCCC, 2011) will be analysed because it may provide an insight into whether the CDM facilitates an environment in Brazil for hydropower projects to be installed with an over emphasis on economic benefits. It should contribute to further understanding and

clarification of how far issues of distribution, recognition and participation resonate within a critical procedural document written by the overarching, influential CDM body. Further to that, it may provide information as to the influence that the CDM procedures carry in Brazil when considering the documents representing the CDM in practice which will follow. The second and third documents to be analysed will be the Project Design Document (PDD) (2006) and the validation report (carried out by consultancy, SGS in 2006) for the hydropower project being studied (this will be introduced in the next section) as an example of the CDM in practice. The former of the two documents holds significance because it will show crucial evidence as to the relationship between CDM project planning and distribution, recognition and participation; telling us whether the misrecognition of certain groups and individuals that has taken place in some Brazilian policies (Arestis and Saad Filho, 2007) is repeated within the CDM in this context. The latter of the two is crucial because it shows what standards the relevant Brazilian developers set themselves in the three criteria mentioned above. Also, it indicates what is considered to be acceptable by the CDM board in relation to the three criteria. The fourth and final document is the so called Danish Text mentioned in Chapter 1.1. The analysis of this document is important because of its significance within the political economy of Brazil. Avoiding beginning the analysis here, Chapter 1.1 outlined that the consensus regarding the document upon it being leaked during the Summit was that developing nations would receive few benefits if the proposal was agreed on. Written by

28 developed nations, the document reflects what measures in current and future environmental policy are considered acceptable by the Global North. Therefore, as Brazil is considered one of three or four nations that may have to slow growth rates in order to contribute to mitigate the effects of climate change, the Danish Text is of great significance. Primarily, it can be considered that the document equates to developed nations planning the future of developing ones in a non participatory fashion which is an injustice of great proportion at this scale.

2.4 Case Study: Campos Novos

The chosen case study for this research is a CDM hydropower project in an area called Campos Novos in Santa Catarina, a southern region of Brazil.

Above: Hydroelectric Dam at Campos Novos, Santa Catarina, Brazil (Venturi, 2011)

This particular project was chosen because of the controversy that it has stirred during its life as a valid CDM installation. According to International Rivers (2006), the 626 foot tall dam suffered a huge loss of water due to structural damage in June 2006. The cracks in the dam

29 were so large that the entire reservoir depleted over a few days but was luckily prevented from doing incredible amounts of damage as another dam further downstream was lying almost empty at the time and held the water. Particularly controversial for both the MAB and International Rivers was the validation of the dam as a CDM project after it had been completely constructed. According to Barbara Haya (2007), a campaigner for International Rivers, the very fact that the project was operational without CDM credits should disqualify it from any consideration for CDM credits with its construction beginning in 2001 before the CDM was operational. The controversy that has surrounded the dam resulted in the projects CDM validation being terminated in 2009. However, this should not undermine the relevance of the case study to this research. From previous research by International Rivers (2006, 2007 and 2009) and significant coverage by global media sources, issues of environmental justice appear central to the projects termination and indicate the relevance of choosing the case for the subject of this research.

30

3 Analysis

In following Chapter 2.1, this section will take the form of analysing the documents mentioned in the previous section by way of the three chosen criteria of environmental justice; distribution, recognition and participation. Throughout the section, references will be made to selected components of each document. The breakdown of each document is available in the appendix (Chapter 6) and each selected quote is numbered. For efficiency, references to quotes in the documents may be done using a bracketed number such as (2) when making a point. Ideally, Chapter 6 should be used simultaneously in conjunction with this section for the best understanding of the analysis.

3.1 Distribution

In the procedural document, point (1) notes that only UNFCCC admitted observer organisations (UNFCCC, 2011) are able to attend meetings held by the UNFCCC and the CDM Board. There is an application process for an organisation to be admitted, proposing that anyone can be included. However, the Board has the final say, giving it the opportunity to make tactical decisions if necessary and questioning the equity of membership. In conjunction with this, point (2) identifies another possible obstacle in the way time is distributed to admitted observers (ibid, 2011). There is a specific portion of time distributed for all stakeholders to voice their opinions and issues regarding the CDM at UNFCCC and CDM meetings. It is logical to assume that this might result in numerous stakeholders being unable to voice concerns of their own or on behalf of others (perhaps an organisation that is not admitted). With obstacles to being admitted as an observer, stakeholders also face the issue of inequitable distribution of information from the procedural level. Point (8) suggests that when critical decisions or overhauls of CDM policy are made, information as to the reasons for the changes will be made available to stakeholders when appropriate (ibid, 2011).

31 Linking in with point (1), point (11) also raises issues of inequitable distribution in terms of which stakeholders are invited to periodic stakeholder consultation (ibid, 2011) workshops. These workshops are proposed in order for stakeholders to better understand CDM policy but point (11) shows that only stakeholders that the CDM Board considers appropriate at that time will be invited. Understandably, efficiency is an issue but the point does not suggest a rotational basis of invites to stakeholders to ensure equitable distribution of the opportunity to participate. In the Project Design Document (PDD) (UNFCCC, 2006), the equity of the distribution of benefits of the dam at Campos Novos is questionable. According to the PDD, the dam was meant primarily to meet the rising demand for energy due to economic growth and improve electricity (UNFCCC, 2006). Although point (1) refers to aiming to meet economic and social elements of sustainability, the priorities appear to be the former, suggesting the possibility that sustainability benefits might be considered less important to the developers of the dam. Point (1) of the validation document links with point (1) of the PDD through its explanation that the dams construction was focused on the identification of significant risks for project implementation and generation of CERs, (SGS, 2006). Again, the priorities of the dams construction appear to be ensuring the distribution of benefits for those that develop it i.e. CERs that can contribute to a companys emission reduction targets as opposed to groups and individuals from civil society, for example. Referencing back to point (1) of the PDD, point (2) of the validation document also has a connection. Considering the aim of (1) to improve social sustainability, the distribution of employment outlined in (2) states only part of the employment generated will be absorbed by regional manpower, (SGS, 2006). There is no indication as to exactly how many jobs can be taken locally, potentially resulting in an inequitable distribution of labour either in favour or not in favour of those that fall under the category of regional.

32 Point (1) of the Danish Text (2009) indicates that the suggested distribution of climate funds would ideally be conditional, based on appropriate action from developing countries. Also, there is no definition in the document of what appropriate equates to. This means that distribution of critical funding to mitigate climate change effects could be denied if developing nations do not meet [X] standard either directly or indirectly. Point (4) raises issues that are particularly relevant to the CDM. The distribution details of the deployed technology (Danish Text, 2009) to aid climate change mitigation and adaption are not available but it seems as though developing countries (see points (5) and (6) of the Danish Text) would be the main recipients (as they are, at the moment through the CDM) of such installations. If this is this case, it could be considered to be inequitable because any impacts from the technology would mostly (or totally) felt by developing nations such as Brazil. Finally, point (9) of the Danish Text should be considered as creating a possible situation of inequitable distribution of finance for climate change adaption and mitigation. With a suggestion that the World Bank should become the superior climate change financier instead of the UN, This could alter the way climate change finance is viewed and distributed.

3.2 Recognition

Point (1) of the procedural document presents the possibility of misrecognising stakeholders that are not UNFCCC observer organisation (UNFCCC, 2011). An example of this misrecognition can be taken from the MAB, a stakeholder central to the criticism of the dam at Campos Novos, not being one of the admitted organisations. Although it is not clear whether an application has been made for membership, the MAB are a well - known organisation in documenting the effects of dams on people across the world and the information they hold might have been, or still might be useful to the UNFCCC and CDM Board.

33 A consistent theme across the procedural document seems to be the misrecognition of the potential value of stakeholders information, views and opinions on matters of CDM policy in terms of modalities and in practice. Points (2), (4), (5) and (10) all state in a loose form that the views of stakeholders are allowed during various meetings, workshops, creation or overhaul of CDM policy. However, all these positive points are littered with words of conditionality such as may, appropriate, consideration and time slot, allowing for the opportunity to disregard the opinions and views of all stakeholders. The overarching feeling from the procedural document (demonstrated by point (13)) is that the CDM Board will allow stakeholders to communicate their views but this does not mean that the Board have to recognise their sense, importance or significance in relation to a CDM project, meaning they may go largely ignored. As can be seen from point (2) of the PDD, the request for comments from local stakeholders in regards to the dam at Campos Novos, (UNFCCC, 2006) did not cover a great deal of different organisations in its call, meaning that key stakeholders that may have had important opinions or information regarding the dam and its effects may not have been recognised. Further to that, point (10) of the validation document shows that the opportunity to make these comments was only 30 days long. While there must be a time limit for the purpose of efficiency, this seems too short a time to indicate recognition of the various efforts from different stakeholders needed to gather information and prepare arguments or responses in regards to the dam. Point (4) of the PDD notes that No concerns were raised in the public calls regarding the project (UNFCCC, 2006). On the contrary, International Rivers (2007) have raised numerous concerns regarding the project. This is suggestive but speculative that perhaps the correct recognition was not given to the value of the opinion of International Rivers at the time of the PDD and validation.

34 Point (2) of the validation document describes the demand for workers generated by the dam at Campos Novos. The document indicates a profile for the ideal worker as someone with a few years education (SGS, 2006), possibly misrecognising and discriminating against the more skilled workers looking for employment. Looking at points (1) and (2) of the Danish Text, it seems that possible instances of misrecognition can be identified in this proposed Convention. Point (1) suggests that climate change adaption funds for developing countries should be based on appropriate (Danish Text, 2009) efforts to mitigate GHGs. As has been mentioned, it is difficult to clarify what mitigations will be accepted as appropriate which means that while a country such as Brazil might make reductions, it is possible for these reductions to not meet set standards. However, point (2) notes that periodic reviews on mitigation efforts will be based on GDP, emission levels and level of development. This proposal misrecognises the fact that GDP might not be appropriate to measure efforts to mitigate because it is largely an economic measure and may not recognise social or cultural problems contributing to a sub appropriate mitigation effort and in consequence a loss of climate change finance. Point (6) of the Danish Text appears to champion the potential contribution to mitigation efforts that international offset credits will continue to make. Put into context, this means that the generation of CERs still holds great importance. Subsequently, this requires more installations of CDM projects in developing countries in order for this generation to take place, potentially reinforcing similar instances of inequitable distribution, misrecognition and issues of participation.

3.3 Participation

Lack of stakeholder participation appears to be a problem within the CDM whether at the procedural level or in practice. Taking points (1) and (2) of the procedural document, it is clear that for an organisation, the barrier to participating in CDM processes is having to gain

35 accreditation from the UNFCCC. Also, the second point indicates that even when accreditation is gained by an organisation, it may have difficulty voicing a concern or opinion due to the allocated time slot for interaction (UNFCCC, 2011) and that discussions at such meetings should not take on the form of case specific matters (ibid, 2011), making it seemingly very difficult to make meaningful participation in these situations. Point (4) of the same document reinforces the lack of participation with CDM procedures. It says that the Secretariat invites comments from stakeholders (ibid, 2011) but these issues are not guaranteed to be dealt with; only brought into consideration (ibid, 2011). This means that a stakeholder could be invited to comment numerous times, raising the same issue in each instance and never see it dealt with (though this is an extreme example). In terms of writing new or altering current CDM policy, point (5) shows that the call for input from stakeholders is not always asked for by the CDM Board. If it is asked for, this request can be made before or after major changes have been made. This renders stakeholder participation to be rather meaningless if they are sometimes consulted and sometimes not. In fact, point (9) suggests that the Board is more concerned with helping stakeholders with enhancing understanding of CDM rules (ibid, 2011) rather than multi stakeholder decision making. Point (12) states that based on the forecasted need to meet with stakeholders, the number of Board and stakeholder meetings will be decided appropriately. This shows that stakeholders do not have the power or influence to organise meetings with the Board, rather it is done at the Boards discretion. Subsequently, it could mean that if a stakeholder has a problem with CDM implementation in some way, shape or form, it might not be addressed in time because stakeholders are not in a position to ask the Board to participate. Point (3) of the PDD notes that no concerns were raised in the public calls (UNFCCC, 2006) regarding the dam at Campos Novos. From previous sections of this chapter it is clear that concerns did arise but just outside of the 30 day period in which stakeholders had

36 the opportunity to participate. Further substantiating the point, International Rivers stated specifically that there had been a lack of stakeholder consultation (Haya, 2007) i.e. a lack of participation. According to point (4) of the validation report, when the PDD was completed, comments were invited by stakeholders but only through the UNFCCC CDM webpage. For some stakeholders in the process, this may have caused an obstacle to participation because of having no access to the Internet, for example. In points (3), (4), (5), (6), (7), and (8) of the Danish Text, the issue of participation is very prevalent. It seems in all the above points in the draft Convention that its authors were intent on gaining political commitment for the bulk of climate change mitigation and adaption efforts to be carried out by developing countries. Taking the example of point (5), the document speaks of substantially increased finance for climate efforts in developing countries. Of particular relevance to this research, point (6) of the document states that the purchase of international offset credits will play a supplementary role to domestic action. As previously mentioned, the CDM would have a large role to play in this, meaning that countries such as Brazil would need to welcome more CDM installations in order to achieve this goal. To avoid repetition of the same point, the participatory element of the Danish Text is that participation in climate change mitigation and adaption will fall largely on the developing countries of the world. It does appear that developed countries are willing to provide both finance (see (5)) and technology (see (7)) but the provisions are for aiding the efforts in developing countries to have a more global impact.

3.4 Evaluation

It seems the issues of distribution, recognition and participation all occur within the documents that have been analysed in this section.

37 Bar the Danish Text, a similarity between all the documents that must be considered to be positive is that recognition and participation are usually offered in one form or another to stakeholders in regards to CDM policy. However, it is often done so with many conditions that subsequently weaken the potential impact or influence that stakeholders outside of the procedural level can have on policy. It would seem that although participation, recognition and equitable distribution are mostly presented as something that all parties are interested in (and CDM policy claims to require it), those at the procedural level may value it as less important than achieving overall goals for projects such as Campos Novos. The problem here is that the overall goals do not seem to directly fall in line with climate change mitigation (an aim of the CDM). Moreover, the goals are associated with the maximum generation of CERs which could either be used by a company to emit more carbon or to sell on through the carbon market. The Danish Text has helped to facilitate the meta ethical (Frankena, 1988) policy analysis because it allows readers to see that the realm of (future) environmental policy making is loaded with value judgements (ibid, 1988) regarding distribution, recognition and participation even at such a high level. Although the way these criteria are valued is not stated directly by the documents, the analysis is such that it might be inferred that because they are not prioritised at any of the different procedural scales (Danish Text, CDM Procedures, PDD and validation), they are not valued as highly as other goals such as generating CERs. It seems only natural that the values held by some at the level of national governments of the developed world would be repeated through the policies which they propose and create (Danish Text and CDM) and through policy implementation (evidenced by the PDD and validation documents) and this is a major problem. On the other hand, it is arguable that some level of participation and recognition is much better than nothing. For instance, it would be far more of a disgrace if stakeholders were unable to give their opinions at all; that CDM policy was constructed without the aim of

38 distributing some benefits to stakeholders other than the developers or financiers; that no stakeholders were given the opportunity to be recognised as UNFCCC accredited observer organisations; but this is not the case. CDM policy does give consideration to distribution, recognition and participation but it is done so at a certain scale that, whether purposeful or not, always keeps stakeholders at an arms length. Using one example to demonstrate this, the UNFCCC application process to become an observer organisation is available to any group or individual. However, the applications must be filled out online and this may not be possible for certain stakeholders, misrecognising that gaining access to the Internet might not be viable for all relevant stakeholders in the process. While 3 of the documents are able to explain the way in which distribution, recognition and participation are considered by CDM policy, the analysis of the Danish Text has reinforced thoughts originally made earlier in this paper regarding the approach to policy problems at present. It demonstrates that instead of, as Young (1990) proposed, trying to understand the social context in which unjust distributions exist, (Schlosberg, 2007), national governments of developed countries are concerned with finding a way out that allows injustices of distribution, recognition and participation to continue.

39

4 Conclusions

What this research was originally centred on was the discrepancies between CDM discourse and practice. The original assumption was that the CDM discourse would be written so that equitable distribution, participation and recognition were important elements of it. However, although these elements are considered, this consideration seems to be more part of a protocol that must be followed in order to prevent outrage from certain stakeholders. Overall, it seems that the minimum attention that these three elements receive is felt across all levels from what is seen on the ground in practice, all the way up the scales to the level of national governments. . It appears this behaviour could be endemic not only in CDM policy but also in the plans for global environmental policy. Overall, cost efficiency and CER generation seem to be the twisted priorities of developed governments in relation to the CDM.

4.1 Recommendations

An idea for future research is to analyse the history of CDM projects. Before the dam at Campos Novos was put forward in application for CDM validation and CERs, it was still operational (Haya, 2007). This means that there must be other planning documents that outline the processes that saw the dam through from paper to the finished article. It would be interesting to see whether levels of distribution of benefits, stakeholder participation and recognition were of concern to the parties involved in the building of the dam. Comparing how far these three criteria resonate in original planning documents with CDM planning documents might conjure up some fascinating results and perhaps say something about how different the CDM might really be (or not be) from conventional planning processes of hydropower installations. From this, inferences could be made on whether the CDM is a positive or negative addition in this respect.

40 In closing, it is a common conception that large, multinational bodies with government influence such as the UNFCCC are in place to do good things. While this might be the case, it seems that the policies it creates do not hold all people as equal; a mistake that should be avoided in such critical global legislation. To counteract this status quo and create a strategy to improve these policies seems impossible due to the apparent impenetrability of such bodies. However, it should be remembered that knowledge is power and, using the evidence that can be generated by a policy analysis such as this, perhaps progress can be made. Particularly, advocates of movements such as climate justice that are concerned with the creation of policies that perpetuate discrimination (Mobilization for Climate Justice, 2011) could consider that it does not take a professional analyst to unpack these policies. With that in mind, the UNFCCC and CDM may not seem as impenetrable as first thought and with enough of well evidenced activism, perhaps changes could be made to CDM policy as a start to making global environmental policy and equity one of the same.

41

5 Bibliography

Arestis, P., and Saad Filho, A., (2007). Political Economy of Brazil: Recent Economic Performance. New York: Palgrave Macmillian Barry, B., (1995). Justice as Impartiality. Oxford: Oxford University Press Draft, (2009). Draft 271109: Adoption of The Copenhagen Agreement Under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change The Danish Text. Available at: < http://www.internationalrivers.org/node/4893> [Accessed 20/08/2011] European Union (2000). Green Paper on greenhouse gas emissions trading within the Euopean Union COM (2000)87. Available at <http://ec.europa.eu/environment/docum/0087_en.htm> [Accessed 10/07/2011] Fraser, N., (1997). Justice Interruptus: Critical Reflections on the Postsocialist Condition. New York: Routledge Frankena, W.K., (1988). Ethics [2nd Edition]. Prentice Hall. Grubb, M., Azar, C., and Pearson, M.U., (2005). Allowance Allocation in the European Emissions Trading System: A Commentary. Climate Policy 5, pp. 127 36 Haya, B., (2007). International Rivers Comments on Campos Novos Dam [Online 03/12/2007]. Available at: <http://www.dnv.com/focus/climate_change/Projects/ViewComment.asp?CommentId =504&ProjectId=1565> [Accessed 15/08/2011] Honneth, A., (1995). The Struggle for Recognition: The Moral Grammar of Social Conflicts. Massachusetts: MIT Press International Monetary Fund, (2011). IMF Standby Arrangement. Available at: < http://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/facts/sba.htm> [Accessed 24/08/2011]. International Rivers, (2006). Campos Novos Dam Builders Downplay Danger [Online June 27th]. Available at: < http://www.internationalrivers.org/en/latin-

42 america/paraguay-paran%C3%A1-basin/campos-novos-dam-builders-downplaydanger> [Accessed 21/08/2011] International Rivers, (2007). Comments on Project Design Document for Campos Novos Dam, Brazil [Online December 1st]. Available at: <http://www.internationalrivers.org/es/global-warming/carbon-trading-cdm/commentsproject-design-document-campos-novos-dam-brazil> [Accessed 21/08/2011] International Rivers, (2009). Campos Novos: Validation terminated as of August 2009 [Online 1 December]. Available at: < http://www.internationalrivers.org/es/globalwarming/carbon-trading-cdm/comments-project-design-document-campos-novosdam-brazil> [Accessed on 28/07/2011] Kyoto Protocol, (1997). Article 4: Commitments. Available at: <http://unfccc.int/essential_background/convention/background/items/1362.php> [Accessed 23/07/11] Luna, F.V. and Klein, H.S., (2006). Brazil Since 1980. New York: Cambridge University Press Meadows, D.H., Randers, J., and Meadows, D.L, (2004). Limits to Growth: The 30Year Update. USA: Chelsea Green Publishing Company Mobilization for Climate Justice, (2011). What is Climate Justice? Available at: < http://www.actforclimatejustice.org/about/what-is-climate-justice/> [Accessed 22/08/2011] Nussbaum, M.C, (2000). Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press Official Journal of the European Community, (2009). Establishing a scheme for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Community and amending Council Directive 96/61/EC (Text with EEA relevance). Available at: < http://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32003L0087:en:NOT> [Accessed 1/07/2011]