Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tran

Uploaded by

Patricia BezneaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tran

Uploaded by

Patricia BezneaCopyright:

Available Formats

Research Capsule

Pancreatology 2009;9:729–737 Published online: January 15, 2010

DOI: 10.1159/000264638

Functional Changes after Pancreatoduodenectomy:

Diagnosis and Treatment

T.C. Khe Tran a Jan J.B. van Lanschot a Marco J. Bruno b Casper H.J. van Eijck a

Departments of a Surgery and b Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Erasmus Medical Center,

Rotterdam, The Netherlands

Key Words the functional changes after pancreatoduodenectomy are

Pancreatoduodenectomy ⴢ Functional changes ⴢ Delayed described in detail with suggestions for diagnosis and treat-

gastric emptying ⴢ Endocrine and exocrine pancreatic ment. Copyright © 2010 S. Karger AG, Basel and IAP

insufficiency ⴢ Enteric-coated capsules ⴢ Quality of life

Abstract Introduction

Relatively little is known about the gastrointestinal function

after recovery of a pancreatoduodenectomy. This review fo- Surgery is the cornerstone of treatment with curative

cuses on the functional changes of the stomach, duodenum intention for patients with tumors of the pancreatic head

and pancreas that occur after pancreatoduodenectomy. Al- and the periampullar region. Radical resection by means

though the mortality in relation to pancreatoduodenecto- of pancreatoduodenectomy offers the only chance for

my has decreased over the years, it remains associated with cure. Partial pancreatoduodenectomy was introduced in

considerable morbidity, which occurs in 40–60% of patients. the beginning of the 20th century by Codivilla and

Physical complaints early after the operation are often Kausch. A modification of the classical partial pancrea-

caused by motility disorders, in particular delayed gastric toduodenectomy as popularized by Whipple et al. [1] is

emptying, which occurs in up to 40% of patients. During lon- the pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy (PPPD),

ger follow-up of these patients the occurrence of endocrine first described by Watson [2] in 1944. Preserving the py-

and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency becomes more pre- lorus is thought to have various advantages, such as sim-

dominant. Diabetes mellitus develops in 20–50% of patients plification of the operation and improvement of postop-

after a pancreatic resection (pancreatogenic diabetes). The erative gastrointestinal function without any negative

main presenting symptoms of exocrine insufficiency are oncological consequences for the patient [3]. To date,

weight loss and steatorrhea. Its presence is suspected on three randomized studies compared the classic Whipple’s

clinical ground and can be supported by fecal elastase-1 operation with PPPD. Two relatively small studies report-

measurement. Exocrine insufficiency can be compensated ed that the pylorus-preserving procedure was associated

with oral enteric-coated enzyme supplements. The quality with shorter operation time, less blood loss, less blood

of life issue will be addressed as an important outcome mea- transfusion and a lower morbidity rate in comparison to

surement after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Furthermore, the classic Whipple procedure [4, 5]. In contrast, our own

© 2010 S. Karger AG, Basel and IAP T.C.K. Tran

1424–3903/09/0096–0729$26.00/0 Department of Surgery

Fax +41 61 306 12 34 Erasmus Medical Center, ’s Gravendijkwal 230

E-Mail karger@karger.ch Accessible online at: NL–3015 CE Rotterdam (The Netherlands)

www.karger.com www.karger.com/pan Tel. +31 10 4633 854, Fax +31 10 4633 350, E-Mail t.tran @ erasmusmc.nl

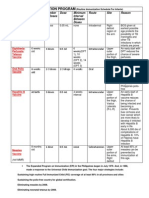

Table 1. Functional changes of the stomach, duodenum and pancreas after pancreatoduodenectomy

Functional changes Incidence Presentation Diagnosis Treatment

Stomach

Delayed gastric emptying 15–40% nasogastric tube >10 days gastric emptying recovery

inability to tolerate a regular scintigraphy <6 months

diet ≥14th day p.o. erythromycin쏐

Duodenum

f Pancreas-stimulating hormones 100% altered digestion process failure to thrive symptomatic

Peptic ulcer formation <5% proton pump

inhibitors

Pancreas

Diabetes mellitus 20–40% hyperglycemia f glucagon hormonal

d insuline insensitivity regulation

Exocrine insufficiency unknown algorithm figure 1 figure 1 figure 1

randomized multicenter study [6] found no difference dence between 15 and 40%. DGE is defined as gastric sta-

between both procedures in operation time, blood loss, sis requiring nasogastric intubation for ten days or more

delayed gastric emptying, hospitalization time, or overall or the inability to tolerate a regular diet on the 14th post-

survival rate. operative day [19]. Whether or not the pylorus is pre-

In spite of the still relatively high morbidity resulting served does not seem to have a great impact in the occur-

from the extensive and invasive surgical procedure, pan- rence of delayed gastric emptying [6]. There is a decrease

creatoduodenectomy is increasingly being performed. in the subjective perception of the occurrence of belching

This is partly because of a considerable reduction in peri- and nausea after Whipple’s operation due to the absence

operative mortality. In high-volume centers, a mortality of mechanoreceptors as a result of the partial stomach

rate of less than 2% has been reported [7–12]. Because of resection [20]. Other causes of DGE after pancreatoduo-

these advances, the assessment and improvement of denectomy are the presence of peritonitis as a result of

short- and long-term postoperative quality of life have postoperative complications such as intra-abdominal ab-

become important topics. Many publications have re- scesses, leakage of the pancreatojejunostomy, ischemia of

ported on quality of life issues after pancreatoduodenec- the antropyloric muscles and reoperation [21, 22]. Objec-

tomy [2, 13–18]. However, relatively little is known about tive quantification of DGE is difficult. In daily practice,

the gastrointestinal function after recovery of a pancre- gastric scintigraphy is the preferred method to determine

atoduodenectomy. DGE. For this purpose, technetium (20 MBq99m hepatate)

This review focuses on the functional changes of the labeled semi-solids or a technetium (20 MBq 99mTc-

stomach, duodenum and pancreas that occur after pan- pertechnetate) labeled pancake are used. Normal half-

creatoduodenectomy. The various factors and mecha- emptying time varies between 38 and 83 min after intake.

nisms that are involved will be described with recom- In general, this investigation is considered too time con-

mendations for diagnosis and treatment. suming and too much of a burden for patients in the ear-

In table 1, a summary is given of the functional chang- ly postoperative phase and a presumptive diagnosis is

es of the stomach, duodenum and pancreas after pancre- usually made on clinical grounds.

atoduodenectomy. Naritomi et al. [23] showed that a low serum level of

motilin delays gastric passage in these patients. In a ran-

domized, placebo-controlled study of 118 consecutive pa-

Changes in Gastric Function tients undergoing a pancreatoduodenectomy, Yeo et al.

[24] have shown that the administration of erythromycin,

Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) is a leading cause which has not only antimicrobial but also prokinetic ac-

of morbidity after pancreatoduodenectomy, occurring tivity, stimulates gastric evacuation. They found a signifi-

early after the surgical procedure with an estimated inci- cantly reduced need to reinsert a nasogastric tube and a

730 Pancreatology 2009;9:729–737 Tran /van Lanschot /Bruno /van Eijck

significantly reduced retention of liquids in the group of tients already suffering from diabetes preoperatively and

patients that was treated with erythromycin. Besides a number of patients developing diabetes de novo.

erythromycin, most commonly used prokinetics are Controversy remains whether diabetes is a risk factor

metoclopramide, domperidon and cisapride with variable for the development of pancreatic cancer or whether pan-

clinical relief of symptoms. The value of new prokinetics, creatic cancer causes diabetes. There are compelling data

including mosapride citrate (a selective agonist for 5-hy- that long-standing diabetes might increase the risk of

droxytryptamine-4 receptors), itopride hydrochloride (a pancreatic cancer [27–30]. However, in simple cross-sec-

benzamide derivative with both dopamin D2 receptor an- tional studies (recent-onset) diabetes is frequently diag-

tagonism and acetylcholinesterase inhibition) and GM- nosed in combination with pancreatic cancer. This is an

611 (an erythromycin-derived motilin agonist) has not yet argument against preexisting diabetes mellitus being a

been fully investigated and therefore these drugs are not risk factor for pancreatic cancer. Probably, these observa-

yet regularly used in clinical practice. In general, the gas- tions can neither be fully explained by destruction of the

tric emptying function gradually recovers spontaneously endocrine pancreas, but rather seem to be partly the re-

to the preoperative level by 6 months after PPPD. sult of a remote effect of the tumor causing impaired glu-

cose metabolism. An interesting clinical observation is

the fact that in some patients the diabetes disappears

Changes in Duodenal Function postoperatively [31].

On the other hand, preoperative obstruction of the

With the resection of the largest part of the duode- pancreatic duct is associated with the development of di-

num, the major digestive processes are disturbed and the abetes mellitus as a result of destruction of the parenchy-

delicately controlled digestive chain between the stom- ma [32]. In our own experience [33] patients with an iat-

ach, duodenum and pancreatobiliary secretions is dis- rogenic pancreatic duct occlusion during a pancreatodu-

rupted. A reduced production of pancreas-stimulating odenectomy develop significantly more diabetes mellitus

hormones such as gastrin, cholecystokinin (CCK) and se- in comparison to those who had a pancreatojejunal anas-

cretin leads to an inadequate pancreatic secretion of bi- tomosis.

carbonate. As a result, the gastric content is not neutral- The type of glucose intolerance which results from

ized to an optimal pH. Furthermore, a reduced produc- pancreatic resection is termed pancreatogenic diabetes. It

tion of enterokinase by the duodenum leads to an is associated with features distinct from both type I (in-

inadequate activation of pancreatic proteolytic, amylo- sulin-dependent) and type II (insulin-independent, or

lytic and lipolytic enzymes. adult-onset) diabetes [34].

As mentioned before, resection of the pancreatic head Hepatic insulin resistance with persistent endogenous

and duodenum results in a decrease in pancreas bicar- glucose production and enhanced peripheral insulin sen-

bonate secretion and inadequate gastric acid neutraliza- sitivity results in a brittle form of diabetes, which can be

tion. Excretion of this bicarbonate-poor fluid in the rem- difficult to manage. Surprisingly, pancreatogenic diabe-

nant of the duodenum stimulates the development of ul- tes is characterized by a decrease in hepatic insulin recep-

cerations. However, peptic ulcers occur in less than 5% of tor availability and an increase in peripheral insulin re-

patients after pancreatic surgery [25]. A possible explana- ceptor availability [35]. This paradoxical effect is prob-

tion could be the frequent use of octreotide and proton- ably due to the concurrent deficiency in pancreatic

pomp inhibitors postoperatively, although controversies polypeptide and renders the liver resistant to the suppres-

remain regarding their use after a pancreatoduodenec- sant effects of insulin on hepatic glucose production. The

tomy. result of increased hepatic glucagon responsiveness and

diminished hepatic insulin responsiveness is elevated (or

unsuppressed) endogenous glucose production, which in

Changes in Endocrine Pancreatic Function turn results in hyperglycemia together with an enhanced

hypoglycemic response to exogenous insulin in patients

The more extended the resection of the pancreas, the with pancreatogenic diabetes.

greater the risk of endocrine (and exocrine) pancreatic

insufficiency.

The incidence of diabetes mellitus after a pancreatic

resection varies between 20 and 50% [26], with some pa-

Gastrointestinal Function after Pancreatology 2009;9:729–737 731

Pancreatoduodenectomy

Assessment of Endocrine Pancreatic Function to develop exocrine pancreatic insufficiency frequently

in the course of their illness due to destruction of acinar

Diabetes mellitus is defined as a fasting glucose con- cells with replacement of the parenchyma by fibrous tis-

centration 67.0 mmol/l or a random glucose value 611 sue. Deterioration of the exocrine function often occurs

mmol/l [36] or a GTT (glucose tolerance test) level 611 after pancreatic surgery, partly depending on the exten-

mmol/l after 2 h. siveness of resection.

Another important factor regarding the exocrine

function is whether the pancreatoduodenectomy is com-

Treatment of Endocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency bined with a partial resection of the stomach. First of all

there is an inadequate grinding of food particles. Second-

Usually, the treatment of patients with diabetes starts ly, a reduced secretion of secretin and CCK results in a

with diet, weight reduction, and exercise. After a pancre- reduced production of bicarbonate-rich fluid and diges-

atic resection most patients already suffer from maldiges- tive enzymes, such as amylase, lipase and trypsinogen,

tion problems. which are important for the continuation of the diges-

Patients with persistent hyperglycemia are often start- tion. Finally, the resection of the pancreatic parenchyma

ed on one or more oral hypoglycemic drugs. Insulin is also contributes to a decreased production of pancreatic

added if target level of glucose is not attained. Patients juices, leading to maldigestion and malabsorption of nu-

with pancreatogenic diabetes behave differently com- trients postoperatively.

pared to other diabetics with respect to insulin therapy. Although compensatory hypertrophy of the pancre-

These ‘brittle diabetics’ may become unpredictably hy- atic remnant with increased enzyme production has been

poglycemic during maintenance insulin therapy, unre- observed in animal research, this is hardly ever sufficient

lated to meals or exercise. The need for insulin depends to compensate for the induced exocrine insufficiency in

upon the delicate balance between insulin secretion, in- the clinical setting.

sulin resistance and glucagon responsiveness. The type of reconstruction after pancreatoduodenec-

tomy also appears to affect the occurrence of exocrine

loss of function. In some studies [39] a pancreatogastros-

Changes in Exocrine Pancreatic Function tomy is described to cause further deterioration of the

exocrine insufficiency as a result of accelerated inactiva-

From the scant data that are available to date, it is dif- tion of pancreatic enzymes by gastric juices.

ficult to provide an overview of the risk of exocrine insuf-

ficiency and the success or failure rate of supplementa-

tion therapy. The pathophysiology is complex and com- Assessment of Exocrine Pancreatic Function

prises factors such as preoperative exocrine pancreatic

function and the chosen surgical procedure of resection A number of different exocrine pancreatic function

and restoration of gastrointestinal tract continuity. tests are available [40]. The secretin-cerulein intubation

In general, the functional reserve of exocrine pancre- test is often used as the ‘gold standard’. This test involves

atic functions ensures that insufficiency occurs only dur- the collection of gastric juices after intravenous adminis-

ing the course of illness. Up to 90–95% of the pancreatic tration of secretin and measurement of luminal bicar-

enzyme output may be lost before clinical signs of exo- bonate and protein levels. However, it is difficult or even

crine insufficiency develop [37]. impossible to perform postoperatively. Much less elabo-

The most frequently described change in exocrine rate are indirect nonintubation function tests with ad-

pancreatic function after pancreatoduodenectomy is re- ministration of a pancreatic enzyme supplement and the

duced digestion of fat which leads to weight loss, nutrient measurement of the enzymatic breakdown of intralumi-

deficiency and subjective complaints consistent with ste- nally administered products. The most widely used tests

atorrhea [38]. It is extremely difficult to appreciate and for this purpose are the bentiromide or N-benzoyl-L-ty-

unravel the impact of each individual factor that contrib- rosyl-p-aminobenzoic acid test (BT-PABA/PAS test) and

utes to the postsurgical maldigestion. the pancreolauryl (fluorescein dilaurate) test. In the ben-

Most of the data on exocrine pancreatic insufficiency tiromide test, bentiromide is broken down by chymotrip-

after pancreatic surgery arise from studies in patients sin into p-aminobenzoe acid and aminobenzoate acid,

with chronic pancreatitis. This group of patients is known which is absorbed and secreted by the urine. However,

732 Pancreatology 2009;9:729–737 Tran /van Lanschot /Bruno /van Eijck

Pancreatoduodenectomy

Weight loss and steatorrhea

Fecal elastase-1 determination

Abnormal Normal

Enzyme suppletion* Await: weight loss and steatorrhea

No complaints Persisting complaints: weight loss/diarrhea/steatorrhea

Continuation of dose

Adjustment of dose Await: weight loss and steatorrhea

No complaints Persistent complaints

Continuation of dose Adjustment of dose; start PPI

Fig. 1. Algorithm for the diagnosis and

treatment of exocrine pancreatic insuffi-

ciency. * Pancreatine preparations: start

with 25,000–50,000 IU lipase during main No complaints Exclude other pathology such as celiac disease,

meal and 10,000–25,000 IU lipase during bacterial overgrowth, etc.

in-between snacks.

false-positive test results (i.e. exocrine pancreatic insuf- The cholesteryl [14C]octanoate breath test is also a

ficiency is falsely diagnosed) may occur in cases of poor suitable indirect test for this purpose [45, 46]. The test is

absorption due to intestinal resection, delayed gastric based on the intraluminal hydrolysis of cholesteryl-14C-

emptying or rapid intestinal transit. In the pancreolauryl octanoate by pancreatic cholesterol esterase and the sub-

test, fluorescein dilaurate is administered, which is also sequent absorption and rapid metabolization of 14C-oc-

absorbed and secreted by the urine. Preexisting liver dis- tanoic acid to 14CO2. Measurement of 14CO2 in breath

ease, renal insufficiency and malabsorption syndromes allows an indirect estimation of intraluminal hydrolytic

can induce false-positive results. activity and its time course. Only pancreas-specific en-

For clinical practice, the fecal elastase-1 test is an ef- zyme activity is measured since intraluminal activity of

fective test for the evaluation of exocrine pancreatic in- cholesterol esterase is of pancreatic origin only.

sufficiency [41–44]. This test has a number of advantages.

First, the enzyme is not degraded during intestinal trans-

port; secondly, elastase is concentrated in the feces, and, Treatment of Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency

finally, the enzyme is easily detected by means of an

ELISA test. Especially during the initial phase of exocrine In clinical practice, it is recommended to supplement

pancreatic insufficiency this test shows high sensitivity pancreas enzymes after any form of pancreatic resection.

and specificity. Another advantage of this test is the fact In several studies [47–52] the enteric-coated (mini-)mi-

that the results are not affected by the use of enzyme sup- crospheres are generally the preferred pharmacological

pletion therapy. formulation of pancreatic enzymes. The coating with a

pH sensitive polyacryl acid layer, which only dissolves at

Gastrointestinal Function after Pancreatology 2009;9:729–737 733

Pancreatoduodenectomy

a pH level 15.5, maintains the enzyme integrity in the Proposal for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approach

stomach and therefore improves the efficacy of the en- of Pancreatic Insufficiency

zyme supplements. For this reason, the use of a proton

pump inhibitor postoperatively also helps to increase the In all patients with a condition involving the pancreas,

pH in the proximal small intestine, aiding to achieve a we recommend a fasting glucose level and fecal elastase-1

rapid and proximal release of pancreatic enzymes from determination at onset. If the results are abnormal one

the enteric coat. The coating also masks the unpleasant can start treatment with hormonal regulation and en-

taste of these enzymes. However, one should keep in mind zyme supplementation.

that in patients who already suffer from impaired diges- Apart from decreased insulin production, the increase

tion due to the partial gastric resection, the duodenum in insulin insensitivity combined with the decrease in

resection and the jejunal reconstruction, the enzyme re- glucagon production may play an important part in these

lease from these enteric-coated preparations will be too patients. Therefore, postoperative monitoring of the glu-

slow and therefore the efficacy will decrease. Therefore, cose level is of great importance in order to treat endo-

in order to obtain an optimal therapeutic effect, it is rec- crine pancreatic insufficiency adequately.

ommended to administrate oral enzymes just after the Enzyme supplementation can be started directly after

meals, or even better, distributed along with meals [53]. resuming oral intake postoperatively. The recommended

In figure 1 an algorithm is suggested for diagnosis and start doses of pancreatine capsules are 25,000 to 50,000

treatment of pancreatic exocrine insufficiency. IU lipase during a main meal and 10,000 to 25,000 IU li-

pase during in-between snacks. For an optimal mixture

of food and enzymes, the ingestion of enzymes should

Quality of Life be divided over the meal. The efficacy of treatment is

evaluated by means of repeated measurements of body

Quality of life (QoL) is an important outcome measure weight and history takings of steatorrhea-associated

after pancreatic resection for malignancy because vari- complaints.

ous surgical approaches aimed at prolonged survival can Persistent weight loss and steatorrhea are indications

have a great impact on patient performance. of an inadequate compensation of the exocrine pancre-

Although many studies have addressed the QoL issue, atic insufficiency. In case of an insufficient treatment re-

it is difficult to compare QoL results because of differ- sponse, the dosis should be increased and/or a proton-

ences in methods, study designs and patients character- pump inhibitor should be started. In treatment-resistant

istics in these studies. The instruments used for QoL as- cases other diagnosis such as celiac disease or bacterial

sessment range from visual analogue scales, standard- overgrowth should be considered. The efficacy of treat-

ized health care-related questionnaires in combination ment is evaluated by means of repeated measurements of

with a standard Functional Assessment of Cancer Ther- body weight and history takings of steatorrhea-associat-

apy Hepatobiliary QoL survey [13] to an EORTC QLQ ed complaints. The cholesteryl [14C]octanotate breath test

C30 core questionnaire [16] in combination with a dis- can be used for monitoring.

ease-specific Gastrointestinal QoL index [15, 18]. Most

studies revealed a large decrease in most QoL scales im-

mediately after surgery followed by a slow recovery to Conclusion

preoperative level by 12–24 months after surgery. The

surgical techniques of resection and reconstruction do Motility disorders and endocrine and exocrine pan-

not seem to affect QoL. From a recent study by Morak et creatic insufficiency are frequently encountered after

al. (paper accepted in June 2009 for Cancer), comparing pancreatoduodenectomies. The resulting symptoms have

QoL in patients receiving celiac axis infusion chemother- a substantial impact on the patient’s quality of life. Now

apy/radiotherapy (CAI/RT) after pancreatoduodenecto- that the postoperative mortality after pancreatoduode-

my with QoL in patients without adjuvant treatment, nectomy has substantially decreased, more attention

they found that over a period of 24 months, CAI/RT im- should be focussed on the diagnosis and treatment of the

proved quality of life compared to observation alone in functional consequences after pancreatoduodenectomy.

patients with resected pancreatic and periampullary can- For this purpose, we have indicated a practical guide-

cer. However, these studies contain no information on line.

patients who were operated with a palliative intention.

734 Pancreatology 2009;9:729–737 Tran /van Lanschot /Bruno /van Eijck

T.C. Khe Tran, MD

Currently: Gastrointestinal and Transplant Surgeon, Department of Surgery,

Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

Fellowship Gastrointestinal Surgery: Erasmus MC, Rotterdam,

The Netherlands

Residency: University Hospital-St Radboud, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Jan J.B. van Lanschot, MD, PhD

Currently: Professor and Chairman, Department of Surgery, Erasmus MC,

Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Previously: Professor of Surgical Oncology, AMC, Amsterdam,

The Netherlands

Research Fellowship: Brigham & Women‘s Hospital, Harvard Medical School,

Boston, Mass., USA

Residency: University Hospital-Dijkzigt, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

Marco J. Bruno, MD, PhD

Marco J. Bruno was trained at the Department of Gastroenterology and

Hepatology at the Academic Medical Center (AMC) in Amsterdam under the

supervision of Guido Tytgat. His PhD thesis focused on the efficacy of enzyme

replacement therapy in exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. After his training,

he continued his career as a staff member specializing in the area of hepato-

pancreato-biliary diseases and advanced interventional endoscopy, including

ERCP and EUS. In March 2008, he changed positions and moved to the

Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology of the Erasmus Medical

Center (EMC) in Rotterdam. He is Director of Endoscopy. His clinical and

research activities focus on gastrointestinal oncology and interventional

endoscopy, and he has a special interest in pancreatic diseases. He has

published in many peer-reviewed medical journals, has been a speaker at

numerous international symposia and congresses, and has contributed to

various international live endoscopy workshops.

Gastrointestinal Function after Pancreatology 2009;9:729–737 735

Pancreatoduodenectomy

Casper H.J. van Eijck, MD, PhD

Casper H.J. van Eijck was born January 9th 1957 in Rotterdam, The

Netherlands. He studied medicine at the Erasmus University from 1977 till

1984. He started his surgical residency in 1985 in at the Leyenburg Hospital in

The Hague and after 4 years he finished his residency at the Erasmus Medical

Center in Rotterdam in 1991. He presented his thesis ‘The Role of

Somatostatin Receptors in Breast and Pancreatic Cancer’ in 1993. He is

working at the Erasmus Medical Center and specializes in endocrine and

pancreatobiliary surgery. He became Professor in Surgery in 2009.

References

1 Whipple AO, Parson WB, Mullins CR: Treat- 9 Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB, Staiger DO: Op- 15 Nieveen van Dijkum EJ, Kuhlmann KF, Ter-

ment of carcinoma of the ampulla of vater. erative mortality and procedure volume as wee CB, Obertop H, de Haes JC, Gouma DJ:

Ann Surg 1935;102: 763–779. predictors of subsequent hospital perfor- Quality of life after curative or palliative sur-

2 Watson K: Carcinoma of the ampulla of mance. Ann Surg 2006; 243:411–417. gical treatment of pancreatic and periampul-

vater: successful radical resection. Br J Surg 10 Gouma DJ, van Geenen RC, van Gulik TM, lary carcinoma. Br J Surg 2005; 92:471–477.

1944;31:368–373. de Haan RJ, de Wit LT, Busch OR, Obertop 16 Schniewind B, Bestmann B, Henne-Bruns D,

3 Klinkenbijl JH, van der Schelling GP, Hop H: Rates of complications and death after Faendrich F, Kremer B, Kuechler T: Quality

WC, van Pel R, Bruining HA, Jeekel J: The pancreaticoduodenectomy: risk factors and of life after pancreaticoduodenectomy for

advantages of pylorus-preserving pancre- the impact of hospital volume. Ann Surg ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic

atoduodenectomy in malignant disease of 2000;232:786–795. head. Br J Surg 2006; 93:1099–1107.

the pancreas and periampullary region. Ann 11 van Heek NT, Kuhlmann KF, Scholten RJ, de 17 Schniewind B, Bestmann B, Kurdow R, Tepel

Surg 1992; 216:142–145. Castro SM, Busch OR, van Gulik TM, Ober- J, Henne-Bruns D, Faendrich F, Kremer B,

4 Lin PW, Lin YJ: Prospective randomized top H, Gouma DJ: Hospital volume and mor- Kuechler T: Bypass surgery versus palliative

comparison between pylorus-preserving tality after pancreatic resection: a systematic pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients with

and standard pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br review and an evaluation of intervention in advanced ductal adenocarcinoma of the

J Surg 1999;86:603–607. the Netherlands. Ann Surg 2005; 242: 781– pancreatic head, with an emphasis on qual-

5 Seiler CA, Wagner M, Sadowski C, Kulli C, 788; discussion 788–790. ity of life analyses. Ann Surg Oncol 2006;13:

Buchler MW: Randomized prospective trial 12 Winter JM, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, Ar- 1403–1411.

of pylorus-preserving vs. classic duodeno- nold MA, Chang DC, Coleman J, Hodgin 18 Witzigmann H, Max D, Uhlmann D, Geissler

pancreatectomy (Whipple procedure): ini- MB, Sauter PK, Hruban RH, Riall TS, Schu- F, Schwarz R, Ludwig S, Lohmann T, Caca K,

tial clinical results. J Gastrointest Surg 2000; lick RD, Choti MA, Lillemoe KD, Yeo CJ: Keim V, Tannapfel A, Hauss J: Outcome after

4:443–452. 1423 pancreaticoduodenectomies for pan- duodenum-preserving pancreatic head re-

6 Tran KT, Smeenk HG, van Eijck CH, Kaze- creatic cancer: a single-institution experi- section is improved compared with classic

mier G, Hop WC, Greve JW, Terpstra OT, Zi- ence. J Gastrointest Surg 2006;10:1199–1210; Whipple procedure in the treatment of

jlstra JA, Klinkert P, Jeekel H: Pylorus pre- discussion 1210–1191. chronic pancreatitis. Surgery 2003; 134: 53–

serving pancreaticoduodenectomy versus 13 Nguyen TC, Sohn TA, Cameron JL, Lillemoe 62.

standard whipple procedure: a prospective, KD, Campbell KA, Coleman J, Sauter PK, 19 van Berge Henegouwen MI, van Gulik TM,

randomized, multicenter analysis of 170 pa- Abrams RA, Hruban RH, Yeo CJ: Standard DeWit LT, Allema JH, Rauws EA, Obertop H,

tients with pancreatic and periampullary tu- vs. radical pancreaticoduodenectomy for Gouma DJ: Delayed gastric emptying after

mors. Ann Surg 2004; 240:738–745. periampullary adenocarcinoma: a prospec- standard pancreaticoduodenectomy versus

7 Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, tive, randomized trial evaluating quality of pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenec-

Stukel TA, Lucas FL, Batista I, Welch HG, life in pancreaticoduodenectomy survivors. tomy: an analysis of 200 consecutive pa-

Wennberg DE: Hospital volume and surgical J Gastrointest Surg 2003; 7: 1–9; discussion tients. J Am Coll Surg 1997;185:373–379.

mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 9–11. 20 Shan YS, Sy ED, Tsai ML, Tang LY, Li PS, Lin

2002;346:1128–1137. 14 Nieveen Van Dijkum EJ, Terwee CB, PW: Effects of somatostatin prophylaxis af-

8 Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, Good- Oosterveld P, Van Der Meulen JH, Gouma ter pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduode-

ney PP, Wennberg DE, Lucas FL: Surgeon DJ, De Haes JC: Validation of the gastroin- nectomy: increased delayed gastric empty-

volume and operative mortality in the Unit- testinal quality of life index for patients with ing and reduced plasma motilin. World J

ed States. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 2117– potentially operable periampullary carcino- Surg 2005; 29:1319–1324.

2127. ma. Br J Surg 2000; 87:110–115.

736 Pancreatology 2009;9:729–737 Tran /van Lanschot /Bruno /van Eijck

21 Kamiya T, Kobayashi Y, Hirako M, Misu N, 33 Tran K, Van Eijck C, Di Carlo V, Hop WC, 45 Bruno MJ, Hoek FJ, Delzenne B, van

Nagao T, Hara M, Matsuhisa E, Ando T, Zerbi A, Balzano G, Jeekel H: Occlusion of Leeuwen DJ, Schteingart CD, Hofmann AF,

Adachi H, Sakuma N, Kimura G: Gastric the pancreatic duct versus pancreaticojeju- Tytgat GN: Simultaneous assessments of

motility in patients with recurrent gastric ul- nostomy: a prospective randomized trial. exocrine pancreatic function by cholesteryl-

cers. J Smooth Muscle Res 2002; 38:1–9. Ann Surg 2002; 236: 422–428; discussion [14C]octanoate breath test and measurement

22 Kimura F, Suwa T, Sugiura T, Shinoda T, 428. of plasma p-aminobenzoic acid. Clin Chem

Miyazaki M, Itoh H: Sepsis delays gastric 34 Slezak LA, Andersen DK: Pancreatic resec- 1995;41:599–604.

emptying following pylorus-preserving tion: effects on glucose metabolism. World J 46 Mundlos S, Kuhnelt P, Adler G: Monitoring

pancreaticoduodenectomy. Hepatogastro- Surg 2001;25:452–460. enzyme replacement treatment in exocrine

enterology 2002; 49:585–588. 35 Seymour J: Diabetes blood glucose monitor- pancreatic insufficiency using the cholester-

23 Naritomi G, Tanaka M, Matsunaga H, Yoko- ing. Nurs Times 1995; 91:46–49. yl octanoate breath test. Gut 1990; 31: 1324–

hata K, Ogawa Y, Chijiiwa K, Yamaguchi K: 36 Genuth S, Alberti KG, Bennett P, Buse J, De- 1328.

Pancreatic head resection with and without fronzo R, Kahn R, Kitzmiller J, Knowler WC, 47 Adler G, Mundlos S, Kuhnelt P, Dreyer E:

preservation of the duodenum: different Lebovitz H, Lernmark A, Nathan D, Palmer New methods for assessment of enzyme ac-

postoperative gastric motility. Surgery 1996; J, Rizza R, Saudek C, Shaw J, Steffes M, Stern tivity: do they help to optimize enzyme treat-

120:831–837. M, Tuomilehto J, Zimmet P: Follow-up re- ment? Digestion 1993;54(suppl 2):3–9.

24 Yeo CJ, Barry MK, Sauter PK, Sostre S, Lil- port on the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. 48 Bruno MJ, Borm JJ, Hoek FJ, Delzenne B,

lemoe KD, Pitt HA, Cameron JL: Erythro- Diabetes Care 2003;26:3160–3167. Hofmann AF, de Goeij JJ, van Royen EA, van

mycin accelerates gastric emptying after 37 DiMagno EP: Medical treatment of pancre- Gulik TM, de Wit LT, Gouma DJ, van Leeu-

pancreaticoduodenectomy: a prospective, atic insufficiency. Mayo Clin Proc 1979; 54: wen DJ, Tytgat GN: Comparative effects of

randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Ann 435–442. enteric-coated pancreatin microsphere ther-

Surg 1993; 218:229–237; discussion 237–228. 38 Layer P, Keller J: Pancreatic enzymes: secre- apy after conventional and pylorus-preserv-

25 Grace PA, Pitt HA, Longmire WP: Pancre- tion and luminal nutrient digestion in health ing pancreatoduodenectomy. Br J Surg 1997;

atoduodenectomy with pylorus preservation and disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 1999; 28: 84:952–956.

for adenocarcinoma of the head of the pan- 3–10. 49 Dutta SK, Rubin J, Harvey J: Comparative

creas. Br J Surg 1986; 73:647–650. 39 Jang JY, Kim SW, Han JK, Park SJ, Park YC, evaluation of the therapeutic efficacy of a ph-

26 Stone WM, Sarr MG, Nagorney DM, McIl- Joon Ahn Y, Park YH: Randomized prospec- sensitive enteric coated pancreatic enzyme

rath DC: Chronic pancreatitis: results of tive trial of the effect of induced hypergas- preparation with conventional pancreatic

whipple’s resection and total pancreatecto- trinemia on the prevention of pancreatic enzyme therapy in the treatment of exocrine

my. Arch Surg 1988;123:815–819. atrophy after pancreatoduodenectomy in pancreatic insufficiency. Gastroenterology

27 Everhart J, Wright D: Diabetes mellitus as a humans. Ann Surg 2003;237:522–529. 1983;84:476–482.

risk factor for pancreatic cancer: a meta- 40 Steer ML, Waxman I, Freedman S: Chronic 50 Graham DY: An enteric-coated pancreatic

analysis. JAMA 1995;273:1605–1609. pancreatitis. N Engl J Med 1995; 332: 1482– enzyme preparation that works. Dig Dis Sci

28 Fisher WE: Diabetes: risk factor for the de- 1490. 1979;24:906–909.

velopment of pancreatic cancer or manifes- 41 Beharry S, Ellis L, Corey M, Marcon M, Du- 51 Lankisch PG, Lembcke B, Goke B, Creutzfeldt

tation of the disease? World J Surg 2001; 25: rie P: How useful is fecal pancreatic elastase W: Therapy of pancreatogenic steatorrhoea:

503–508. 1 as a marker of exocrine pancreatic disease? does acid protection of pancreatic enzymes

29 Gullo L, Pezzilli R, Morselli-Labate AM: Di- J Pediatr 2002;141:84–90. offer any advantage? Z Gastroenterol 1986;

abetes and the risk of pancreatic cancer. N 42 Carroccio A, Verghi F, Santini B, Lucidi V, 24:753–757.

Engl J Med 1994;331:81–84. Iacono G, Cavataio F, Soresi M, Ansaldi N, 52 Schneider MU, Knoll-Ruzicka ML, Dom-

30 Yalniz M, Pour PM: Diabetes mellitus: a risk Castro M, Montalto G: Diagnostic accuracy schke S, Heptner G, Domschke W: Pancreatic

factor for pancreatic cancer? Langenbecks of fecal elastase 1 assay in patients with pan- enzyme replacement therapy: comparative

Arch Surg 2005; 390:66–72. creatic maldigestion or intestinal malab- effects of conventional and enteric-coated

31 Murphy R, Smith FH: Abnormal carbohy- sorption: a collaborative study of the italian microspheric pancreatin and acid-stable fun-

drate metabolism in pancreatic carcinoma. society of pediatric gastroenterology and gal enzyme preparations on steatorrhoea in

Med Clin North Am 1963;47:397–405. hepatology. Dig Dis Sci 2001;46:1335–1342. chronic pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterolo-

32 Ohshio G, Tanaka T, Imamura T, Okada N, 43 Gullo L, Ventrucci M, Tomassetti P, Migliori gy 1985;32:97–102.

Yoshitomi S, Suwa H, Hosotani R, Imamura M, Pezzilli R: Fecal elastase 1 determination 53 Dominguez-Munoz JE, Iglesias-Garcia J,

M: Exocrine pancreatic function in the early in chronic pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci 1999;44: Iglesias-Rey M, Figueiras A, Vilarino-Insua

period after pancreatoduodenectomy and 210–213. M: Effect of the administration schedule on

effects of preoperative pancreatic duct ob- 44 Stein J, Jung M, Sziegoleit A, Zeuzem S, Cas- the therapeutic efficacy of oral pancreatic

struction. Dig Dis Sci 1996;41:1947–1952. pary WF, Lembcke B: Immunoreactive elas- enzyme supplements in patients with exo-

tase I: clinical evaluation of a new noninva- crine pancreatic insufficiency: a random-

sive test of pancreatic function. Clin Chem ized, three-way crossover study. Aliment

1996;42:222–226. Pharmacol Ther 2005;21:993–1000.

Gastrointestinal Function after Pancreatology 2009;9:729–737 737

Pancreatoduodenectomy

You might also like

- Current and Future Developments in Surgery: Volume 2: Oesophago-gastric SurgeryFrom EverandCurrent and Future Developments in Surgery: Volume 2: Oesophago-gastric SurgeryNo ratings yet

- Post Whipple, Nutrition ManagementDocument9 pagesPost Whipple, Nutrition ManagementHinrich DoradoNo ratings yet

- Management of Pancreatic FistulasDocument7 pagesManagement of Pancreatic FistulasEmmanuel BarriosNo ratings yet

- World Journal of Surgical Oncology: Alternative Reconstruction After PancreaticoduodenectomyDocument4 pagesWorld Journal of Surgical Oncology: Alternative Reconstruction After PancreaticoduodenectomyPra YudhaNo ratings yet

- Amilaze PredictivDocument7 pagesAmilaze PredictivDumitru RadulescuNo ratings yet

- Pancreaticoduodenectomy or Whipple Procedure: Overview: by Dr. Sreeremya.S Faculty of BiologyDocument11 pagesPancreaticoduodenectomy or Whipple Procedure: Overview: by Dr. Sreeremya.S Faculty of BiologyKhuvindra Kevin Matai100% (1)

- Otherformsof Gastroparesis: Postsurgical, Parkinson, Other Neurologic Diseases, Connective Tissue DisordersDocument13 pagesOtherformsof Gastroparesis: Postsurgical, Parkinson, Other Neurologic Diseases, Connective Tissue DisordersJuan Carlos Flores MejíaNo ratings yet

- Diseases of PancreasDocument3 pagesDiseases of PancreasLaparoscopic surgeon jabalpur digant pathakNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Pancreatoduodenectomy With or Without Pyloric Preservation: A Clinical Outcomes ComparisonDocument9 pagesResearch Article: Pancreatoduodenectomy With or Without Pyloric Preservation: A Clinical Outcomes ComparisonHiroj BagdeNo ratings yet

- Randomized Controlled Study of The Effect of Octreotide On Pancreatic Exocrine Secretion and Pancreatic Fistula After PancreatoduodenectomyDocument6 pagesRandomized Controlled Study of The Effect of Octreotide On Pancreatic Exocrine Secretion and Pancreatic Fistula After PancreatoduodenectomycanerkNo ratings yet

- Complications of Bariatric Surgery Dumping Syndrome Reflux and Vitamin Deficiencies 2014 Best Practice Research Clinical GastroenterologyDocument10 pagesComplications of Bariatric Surgery Dumping Syndrome Reflux and Vitamin Deficiencies 2014 Best Practice Research Clinical GastroenterologyYipno Wanhar El MawardiNo ratings yet

- Periop UrologyKoubaartikelDocument4 pagesPeriop UrologyKoubaartikeljustin_saneNo ratings yet

- Pancreatic Surgery: Presented To DR - Lasha GulbaniDocument24 pagesPancreatic Surgery: Presented To DR - Lasha Gulbani143bbNo ratings yet

- Gastroduodenal PerforationDocument4 pagesGastroduodenal PerforationMaresp21No ratings yet

- Peustow ArticleDocument6 pagesPeustow ArticleAjay GujarNo ratings yet

- Management of The Pancreatic Remnant During Whipple OperationDocument4 pagesManagement of The Pancreatic Remnant During Whipple OperationYacine Tarik Aizel100% (1)

- Whipple Surgical ReportDocument4 pagesWhipple Surgical Reportapi-332047001No ratings yet

- Cholecystitis Treatment & ManagementDocument8 pagesCholecystitis Treatment & ManagementTruly Dian AnggrainiNo ratings yet

- Endoscopic Management in The Bariatric Surgical Patient: Benjamin E. Levitzky and Wahid Y. WassefDocument8 pagesEndoscopic Management in The Bariatric Surgical Patient: Benjamin E. Levitzky and Wahid Y. Wasseflourdes marquezNo ratings yet

- Sumber Jurnal ReadingDocument15 pagesSumber Jurnal ReadingagungNo ratings yet

- Data PDF ManmadhaRaoDocument4 pagesData PDF ManmadhaRaoBhavani Rao ReddiNo ratings yet

- Long Acting Octreotide For The Treatment and Symptomatic Relief of Bowel Obstruction in Advanced Ovarian CancerDocument7 pagesLong Acting Octreotide For The Treatment and Symptomatic Relief of Bowel Obstruction in Advanced Ovarian CancerThiago GomesNo ratings yet

- Complicationsafter Pancreaticoduodenectomy: Robert SimonDocument10 pagesComplicationsafter Pancreaticoduodenectomy: Robert SimonŞükriye AngaNo ratings yet

- Chronic Pancreatitis: DefinitionDocument4 pagesChronic Pancreatitis: DefinitionDrVishwa PrakashNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Pancreatic FistulaDocument6 pagesRisk Factors For Pancreatic Fistulahenok seifeNo ratings yet

- Chronic PancreatitisDocument42 pagesChronic PancreatitismmurugeshrajNo ratings yet

- Optimising The Treatment of Upper Gastrointestinal FistulaeDocument9 pagesOptimising The Treatment of Upper Gastrointestinal FistulaeYacine Tarik AizelNo ratings yet

- Acute Intestinal Failure.11Document6 pagesAcute Intestinal Failure.11albimar239512No ratings yet

- CreonDocument12 pagesCreonNikola StojsicNo ratings yet

- Late Complications of Bariatric Surgical Operations - UpToDateDocument46 pagesLate Complications of Bariatric Surgical Operations - UpToDateMelissandreNo ratings yet

- ConstipationDocument33 pagesConstipationsalmawalidNo ratings yet

- Dumping Syndrome - Background, Pathophysiology, EtiologyDocument6 pagesDumping Syndrome - Background, Pathophysiology, EtiologyW CnNo ratings yet

- Fast-Track Recovery Programme After Pancreatico-Duodenectomy Reduces Delayed Gastric EmptyingDocument7 pagesFast-Track Recovery Programme After Pancreatico-Duodenectomy Reduces Delayed Gastric EmptyinghoangducnamNo ratings yet

- Billroth I & IIDocument5 pagesBillroth I & IIRoxieparkerNo ratings yet

- XX - 2016-11 - Small Amounts of Tissue Preserve Pancreatic Function - Long-Term Follow-Up Study of Middle-Segment Preserving PancreatectomyDocument8 pagesXX - 2016-11 - Small Amounts of Tissue Preserve Pancreatic Function - Long-Term Follow-Up Study of Middle-Segment Preserving PancreatectomyNawzad SulayvaniNo ratings yet

- GR 080013Document3 pagesGR 080013malik003No ratings yet

- Anaesthesia For Pancreatic SurgeryDocument11 pagesAnaesthesia For Pancreatic SurgeryyenuginNo ratings yet

- Postoperative Management and Complications After Abdominal Surgery in Children Receiving Peritoneal DialysisDocument8 pagesPostoperative Management and Complications After Abdominal Surgery in Children Receiving Peritoneal DialysisunpadurologyNo ratings yet

- 01 HepatogastroDocument3 pages01 Hepatogastroyacine26No ratings yet

- Gastrectomy NutritionDocument10 pagesGastrectomy NutritionBalasubramanian NatarajanNo ratings yet

- Impacto Da Terapia AntiCA Na NutricaoDocument6 pagesImpacto Da Terapia AntiCA Na NutricaoTamara Souza RossiNo ratings yet

- 2 Gastric and Duodenal Peptic Ulcer Disease 2Document35 pages2 Gastric and Duodenal Peptic Ulcer Disease 2rayNo ratings yet

- Interventional Approaches Gallbladder DiseaseDocument9 pagesInterventional Approaches Gallbladder DiseaseAntônio GoulartNo ratings yet

- Palliative Stenting With or Without Radiotherapy For Inoperable Esophageal CarcinomaDocument7 pagesPalliative Stenting With or Without Radiotherapy For Inoperable Esophageal CarcinomaBella StevannyNo ratings yet

- Book Reading Chronic Pancreatitis - 0830Document26 pagesBook Reading Chronic Pancreatitis - 0830Short BowelNo ratings yet

- Surgery For Acute Pancreatitis PDFDocument7 pagesSurgery For Acute Pancreatitis PDFValean DanNo ratings yet

- WJS Surgical Treatment GERDDocument6 pagesWJS Surgical Treatment GERDPili RemersaroNo ratings yet

- Management of Adhesive Intestinal Obstruction: Original ArticleDocument3 pagesManagement of Adhesive Intestinal Obstruction: Original ArticleNaufal JihadNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Klatskin Tumor: April 2010Document6 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Klatskin Tumor: April 2010Feby Kurnia PutriNo ratings yet

- ANZ J. Surg. 2008 78 (Suppl. 1) A68-A80Document13 pagesANZ J. Surg. 2008 78 (Suppl. 1) A68-A80Ammar magdyNo ratings yet

- Effect of Billroth II or Roux-En-Y Reconstruction For The Gastrojejunostomy After PancreaticoduodenectomyDocument9 pagesEffect of Billroth II or Roux-En-Y Reconstruction For The Gastrojejunostomy After PancreaticoduodenectomyJoanne AjosNo ratings yet

- Review On Enterocutaneous FistulaDocument31 pagesReview On Enterocutaneous FistulaAbu ZidaneNo ratings yet

- Konstipasi ICUDocument7 pagesKonstipasi ICUHusna LathiifaNo ratings yet

- Pylorus-Preserving Pancreaticoduodenectomy Versus Conventional Pancreaticoduodenectomy For Pancreatic AdenocarcinomaDocument6 pagesPylorus-Preserving Pancreaticoduodenectomy Versus Conventional Pancreaticoduodenectomy For Pancreatic Adenocarcinomafidodido2000No ratings yet

- Management of IntestinalDocument13 pagesManagement of IntestinalSergiu ManNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Peptic Ulcer DiseaseDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Peptic Ulcer Diseaseafmzwasolldhwb100% (1)

- Ultrafiltration Failure in Peritoneal Dialysis: A Pathophysiologic ApproachDocument4 pagesUltrafiltration Failure in Peritoneal Dialysis: A Pathophysiologic ApproachAn-Nisa Khoirun UmmiNo ratings yet

- Background: Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)Document4 pagesBackground: Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)Resci Angelli Rizada-NolascoNo ratings yet

- Rabeprazole Combined With Hydrotalcite Is Effective For Patients With Bile Reflux Gastritis After CholecystectomyDocument5 pagesRabeprazole Combined With Hydrotalcite Is Effective For Patients With Bile Reflux Gastritis After CholecystectomyGabriel IonescuNo ratings yet

- Whipple ComplicationDocument34 pagesWhipple ComplicationMike Hugh100% (1)

- Singhi Lef1Document14 pagesSinghi Lef1Patricia BezneaNo ratings yet

- Tipton 2006Document5 pagesTipton 2006Patricia BezneaNo ratings yet

- Prediction of Malignancy and Adverse Outcome of Solid Pseudopapillary Tumor of The PancreasDocument11 pagesPrediction of Malignancy and Adverse Outcome of Solid Pseudopapillary Tumor of The PancreasPatricia BezneaNo ratings yet

- Medicine: Spontaneous Rupture of Solid Pseudopapillary Tumor of PancreasDocument8 pagesMedicine: Spontaneous Rupture of Solid Pseudopapillary Tumor of PancreasPatricia BezneaNo ratings yet

- TangDocument8 pagesTangPatricia BezneaNo ratings yet

- SalviaDocument7 pagesSalviaPatricia BezneaNo ratings yet

- Song 2017Document8 pagesSong 2017Patricia BezneaNo ratings yet

- TanakaDocument5 pagesTanakaPatricia BezneaNo ratings yet

- YagciDocument7 pagesYagciPatricia BezneaNo ratings yet

- Pancreatic TumorDocument11 pagesPancreatic TumorPatricia BezneaNo ratings yet

- Pancreatic TumorDocument8 pagesPancreatic TumorPatricia BezneaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Social Media Health Communication On Knowledge Attitude and Intention To Adopt Health-Enhancing BehavDocument170 pagesEffect of Social Media Health Communication On Knowledge Attitude and Intention To Adopt Health-Enhancing Behavchukwu solomonNo ratings yet

- Contoh Final Test Dalam Bahasa InggrisDocument3 pagesContoh Final Test Dalam Bahasa InggrisnuramaliaNo ratings yet

- ANSDocument42 pagesANSRakshan T100% (1)

- Endoscopy For Upper and Lower Gastrointestinal Procedures Standard Operating Procedure UHL Gastroenterology LocSSIPDocument15 pagesEndoscopy For Upper and Lower Gastrointestinal Procedures Standard Operating Procedure UHL Gastroenterology LocSSIPIlu SinghNo ratings yet

- Labor Code of The Philippines Volume I - Book 4Document144 pagesLabor Code of The Philippines Volume I - Book 4Joanne CamacamNo ratings yet

- Shibari - Japanese Bondage Techniques - Learn The Most Popular Japanese Art of SeductionDocument57 pagesShibari - Japanese Bondage Techniques - Learn The Most Popular Japanese Art of SeductionFrancisco MartinezNo ratings yet

- APA Jamii Plus Family Medical Cover BrochureDocument8 pagesAPA Jamii Plus Family Medical Cover BrochureADANARABOW100% (1)

- Seminar: Christian Trépo, Henry L Y Chan, Anna LokDocument11 pagesSeminar: Christian Trépo, Henry L Y Chan, Anna LokGERALDINE JARAMILLO VARGASNo ratings yet

- C P P C P P: Ardiology Atient AGE Ardiology Atient AGEDocument3 pagesC P P C P P: Ardiology Atient AGE Ardiology Atient AGEBBA MaryamNo ratings yet

- Wa0002.Document7 pagesWa0002.mustaphasuleiman124No ratings yet

- THYROIDINIUMDocument13 pagesTHYROIDINIUMUnnathi TNo ratings yet

- Endodontics PDFDocument109 pagesEndodontics PDFduracell19No ratings yet

- Sciencedirect: Thalassemia Major May Decrease The Frequency of Febrile Convulsions in ChildrenDocument4 pagesSciencedirect: Thalassemia Major May Decrease The Frequency of Febrile Convulsions in ChildrenZherlynPoetriBungzuNo ratings yet

- Bacteria and Immune Defenses: Helicobacter PyloriDocument4 pagesBacteria and Immune Defenses: Helicobacter PyloriMary Rose SJ JimenezNo ratings yet

- Genetics Notes - Other Patterns of Inheritance & PedigreesDocument4 pagesGenetics Notes - Other Patterns of Inheritance & PedigreesJoseph Dav6657No ratings yet

- Cardiac CatheterizationDocument6 pagesCardiac CatheterizationUzma KhanNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Travel Recommendations by Destination - CDCDocument5 pagesCOVID-19 Travel Recommendations by Destination - CDCAli Ben HusseinNo ratings yet

- Urinary System and Its PathologiesDocument23 pagesUrinary System and Its Pathologiesngachangong victorineNo ratings yet

- Mojwh 08 00237Document9 pagesMojwh 08 00237EndalkNo ratings yet

- AARC Clinical Practice Guideline - Management of Airway EmergenciesDocument7 pagesAARC Clinical Practice Guideline - Management of Airway EmergenciesdoterofthemosthighNo ratings yet

- All Previous Essay Surgery 2Document162 pagesAll Previous Essay Surgery 2DR/ AL-saifiNo ratings yet

- 1000 Plus Psychiatry MCQ Book DranilkakunjeDocument141 pages1000 Plus Psychiatry MCQ Book Dranilkakunjethelegend 20220% (1)

- Approach To Diagnosis of Celiac Disease - UpToDateDocument2 pagesApproach To Diagnosis of Celiac Disease - UpToDatemiguelNo ratings yet

- Induction and Augmentation of LaborDocument20 pagesInduction and Augmentation of Laborjssamc prasootitantraNo ratings yet

- XN-Series Clinical Case ReportDocument82 pagesXN-Series Clinical Case ReportMirian soonNo ratings yet

- EPIDocument5 pagesEPIMarquenash Cruz ViñasNo ratings yet

- Congenital Heart Disease: Education and Practice GapsDocument18 pagesCongenital Heart Disease: Education and Practice GapsAlvaro Ignacio Lagos SuilNo ratings yet

- GST Exemptions DMFS 12Document51 pagesGST Exemptions DMFS 12Anjali Krishna SNo ratings yet

- Angina Pectoris Pharmacological and Acupuncture TherapyDocument5 pagesAngina Pectoris Pharmacological and Acupuncture TherapyEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Hellp 2Document57 pagesHellp 2Angela CaguitlaNo ratings yet

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (42)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (24)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (80)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Summary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Sleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningFrom EverandSleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (328)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeFrom EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (253)

- Gut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerFrom EverandGut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (392)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (169)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- To Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceFrom EverandTo Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (51)

- An Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyFrom EverandAn Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- 12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosFrom Everand12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (207)