GEOSC 340 Spring 2015 DiBiase

Lab 6: Streamflow measurement

Objectives

In this lab, you will apply your understanding of open channel flow hydraulics to analyze a gravel bedded

channel in central PA.

Figure 1. LiDAR-derived elevation and hillshade of Sinnemahoning Creek near Sinnemahoning, PA.

6.0 Summary of provided datasets

You have been provided with a file geodatabase “lab_6_data.gdb”, which includes a 1 m

resolution digital elevation model of a stream reach that spans the USGS gaging station on

Sinnemahoning Creek, PA (Fig. 2).

Name Data type Grid size Description Source

sinne1_dem raster 1m Elevation (m) PAMAP

USGS_gage point feature class N/A Location of USGS gage 1543500 USGS

Figure 2. Summary of provided datasets

6.1 Equations and parameters

For convenience, the relevant equations and parameters for performing hydraulic calculations are

repeated below:

General equations

First, and simplest, is the relationship for conservation of mass between water discharge Q and

the product of cross-sectional-averaged velocity 〈𝑢𝑢〉 and the cross-sectional area A:

𝑄𝑄 = 𝐴𝐴〈𝑢𝑢〉

1

�GEOSC 340 Spring 2015 DiBiase

For a rectangular channel, the cross sectional area A is equal to the channel width w multiplied by

the flow depth H:

𝐴𝐴 = 𝑤𝑤𝑤𝑤

We will use a generalized Darcy-Weisbach friction factor f to describe the flow resistance as the

ratio of the shear velocity u* to the cross-sectional averaged velocity 〈𝑢𝑢〉:

𝑢𝑢∗

𝑓𝑓 =

〈𝑢𝑢〉

Remember that the shear velocity u* is the square root of gravitational acceleration g multiplied

by the flow depth H and the water surface slope S:

𝑢𝑢∗ = �𝑔𝑔𝑔𝑔𝑔𝑔

Next, if we assume steady, uniform flow, we can write the shear stress on the bed τ as:

𝜏𝜏 = 𝜌𝜌𝜌𝜌𝜌𝜌𝜌𝜌

For our purposes, it is more useful to use the non-dimensional shear stress, or shields stress τ*:

𝜏𝜏

𝜏𝜏∗ =

(𝜌𝜌𝑠𝑠 − 𝜌𝜌)𝑔𝑔𝑔𝑔

Here, ρs is the density of the sediment, ρ is the density of the fluid, and D is the median grain size

of the bed material.

Parameters for gravel-bedded rivers

For this lab, we will assume some typical values for self-formed, gravel bedded channels. These

values are based on compilations of field measurements of gravel-bedded rivers worldwide, and

are a good starting point for type of rough analysis we are doing using remotely sensed data

instead of field surveys. For more details on the data sets used for these calibrations, see Parker et

al., 2007 JGR.

First, let’s assume a nondimensional Darcy-Weisbach friction factor that for simplicity does not

vary with flow depth (in a more rigorous analysis, f would decrease with increasing flow depth as

the relative roughness of the bed decreases):

𝑓𝑓 = 0.09

Next, we need to assume a value for the nondimensional critical Shields stress, in order to define

our threshold for initial motion of bed material. This value typically ranges from 0.03-0.06, so we

will use something in the middle:

𝜏𝜏∗𝑐𝑐 = 0.045

Last, gravel bedded rivers are self-formed, in that their cross sections are typically tuned to just be

able to transport the material on the bed. That is, at “bankfull”, the shear stress is only a small bit

higher than the critical shear stress for initial motion:

𝜏𝜏∗𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏 = 1.2𝜏𝜏∗𝑐𝑐

2

�GEOSC 340 Spring 2015 DiBiase

If we make the assumption that the channel geometry is well-adjusted, then we can use this

relationship to estimate the bed material grain size based only on topographic data.

Often times on Earth, it is simpler to just measure grain size in the field, and there are some issues

with adequately capturing the effect of downstream fining in this model, but these methods are a

good starting point when applied to inaccessible landscapes – especially on other planets…

Figure 3. Schematic of channel cross section (modified from USGS)

6.2 Task 1: Extract a water surface long-profile and a channel cross section

For the first task, you will use ArcGIS to extract two elevation profiles from the 1m DEM. Note

that it will likely be necessary to first create a hillshade so you can better see what you are doing.

For most parts of the landscape, the elevation of the airborne LiDAR derived DEM corresponds

to the “bare earth” model. That is, trees, cars, and bridges have been filtered out. However, the

LiDAR sensor cannot see through water, and thus the flat topography in the channels corresponds

to the water surface.

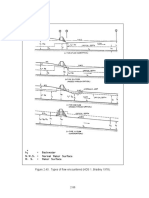

When picking a water surface long-profile, try to stay in the center of the channel, and extend

your profile from the farthest upstream to the farthest downstream reach within view. You will

notice that slope is not constant, but consists of long low sloping reaches separated by short,

steeper reaches. These reflect the pool and riffle morphologies, respectively, which result in

pronounced differences in water surface slope at low flow. At high flow, these differences are

smoothed out (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Pool-riffle morphology in (a) cross section and (b) planview (Dunne and Leopold 1978).

3

�GEOSC 340 Spring 2015 DiBiase

When picking a cross sectional profile, aim to find a generally straight reach (i.e., not the apex of

a meander bend!), and try to capture as natural a flood plain as you can. Be sure to extend your

profile to the valley walls (start of the steep hillslopes), and make sure to scale the vertical

exaggeration such that the channel and floodplain are visible (e.g., Fig. 3)

When you have finished, record the average slope (tangent!) extracted from your water surface

long profile, and use this value for S.

Save the cross section to be annotated later on. You can do this either digitally, OR I will accept

printouts that have been annotated by hand.

6.3 Task 2: Calculate the flow depth at the time of the LiDAR survey

For the second task, you will look up the stream discharge for the date of the topographic survey

(April 29, 2006), and use your elevation profiles and the equations in section 6.1 to estimate the

average flow depth for your cross section (remember the elevation of the DEM corresponds to the

water surface elevation!).

The daily streamflow data for site 1543500 (Sinnemahoning Creek) can be found at the following

website: http://nwis.waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis/inventory/?site_no=01543500

Click on “daily data”, and then edit the “begin” and “end” dates to span April 29, 2006. You can

either read the value off of the graph, or change the output format to “table” or “tab separated”

and read the actual numeric value. NOTE: These data are in units of cubic feet per second. You

will need to convert from cubic feet to cubic meters. 1 cubic foot equals 0.02832 cubic meters.

Next, you will need to use a combination of conservation and friction relationships described

above to determine flow depth. Some tips:

• You may assume a wide, rectangular channel.

• Manipulate the equations to derive a formula for flow depth H before plugging in

numbers

6.4 Task 3: Calculate the bankfull flow conditions for your cross section

Alluvial rivers are responsible for creating their own channels. The fundamental scaling of the

channelized part of the landscape is the “bankfull” flow depth. Above this, rivers flood their

valleys and deposit sediment on floodplains (Fig. 3).

In this section, you will use your cross section to estimate the flow conditions associated with the

bankfull flood. Take some time to think about how to approach this problem. What do you need

to know? What information do you already have? Some tips:

• It may not be appropriate to assume a perfectly rectangular channel, depending on the

geometry of your banks. Be diligent in calculating your cross-sectional area (using

triangles helps...)

• To estimate grain size, take advantage of the commonly observed phenomenon that the

bankfull floods in self-formed gravel channels are just above the critical shields stress for

initial motion (see above equations and parameters).

6.5 Task 4: Build a plot of peak discharge vs. recurrence interval

Go to the USGS website and look up the peak streamflow data for station 1543500 (use the link

above). You should arrive at a page with a chart showing the peak discharge for each year on

4

�GEOSC 340 Spring 2015 DiBiase

record. Notice how most years, the peak is between 10,000 and 20,000 cfs, while only a small

number of years experienced large floods (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Annual peak streamflow for Sinnemahoning Creek, PA

For this lab, we want to analyze the relationship between the magnitude of the annual peak

streamflow events and their frequency of occurrence. This process is referred to as “flood

frequency analysis” and is critical for assessing hazards in flood-prone areas.

First, download the data as a “tab-separated file” by right-clicking and choosing “save link as”

from your browser. Now, open Excel and drag-and-drop the file into the Excel window (Fig. 6).

The data should be organized into columns – if it is not, take some time to clean it up using “text-

to-columns”.

Figure 6. Excel file showing peak streamflow data from Sinnemahoning Creek, PA

We are primarily interested in the column “peak_va”, which contains the peak streamflow data in

cubic feet per second. Create a new sheet and copy/paste the peak streamflow data to the new

sheet.

5

�GEOSC 340 Spring 2015 DiBiase

Next, sort the values from highest to lowest (use the tool data/sort), and then create a second

column with the ranking value (i.e., the highest value should have a rank of 1, and the lowest

value a rank of N, where N is the total number of (annual) observations.

To determine the recurrence interval for each flood, perform the following calculation in a third

𝑁𝑁+1

column: 𝑅𝑅𝐼𝐼 =

𝑅𝑅𝑅𝑅𝑅𝑅𝑅𝑅

Finally, create a fourth column to convert the values of discharge from cubic feet per second to

cubic meters per second. Recall 1 cubic foot equals 0.02832 cubic meters.

Now you can make a plot that shows the annual peak streamflow on the y-axis, and the

recurrence interval on the x-axis. Often it is useful to plot both axes with logarithmic scales.

Lab 6 deliverables, due Wednesday March 18 before lecture (30 pts total)

For this lab, please print out and staple together all work in the order noted below.

(3 pts) An overview map showing the locations of your long profile and cross-section.

• You should know the drill by now. Make it look professional.

(2 pts) A long profile of water surface elevation for the entire reach.

• Be sure to label your axes and indicate vertical exaggeration.

(5 pts) A strategically chosen cross section annotated with the interpretation of the channel bottom,

the low-flow water surface (from the LiDAR topography), and the bankfull water surface.

• Be sure to label your axes and indicate vertical exaggeration.

• Be careful to not mix up the channel bottom and the low-flow water surface – think this one

through…

(5 pts) A plot showing peak discharge vs. recurrence interval for the USGS gage 1543500

• It is probably easiest to plot this on log-log axes

• Indicate the discharge and recurrence interval of the bankfull flood (circle a point and label it)

(15 pts) A completed data table, with all work shown for calculations on a separate page(s)

• Be sure to show all of your work in a clean and logical fashion. Take the time to make it readable.

• Do not forget to include appropriate units.

6

�GEOSC 340 Spring 2015 DiBiase

Table 1. Data calculations.

April 29, 2006 conditions

Parameter Bankfull flood conditions

(LiDAR topo survey)

Slope (S)

Channel width (w)

Flow depth (H)

Basal shear stress (τ)

Median bed material grain size (D) N/A

Water discharge Q

Flood recurrence interval N/A