Professional Documents

Culture Documents

SUSAN - 1982 - Drought and Mexico's Struggle For Independence

Uploaded by

Jorge Luis Angel PerezOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

SUSAN - 1982 - Drought and Mexico's Struggle For Independence

Uploaded by

Jorge Luis Angel PerezCopyright:

Available Formats

Drought and Mexico's Struggle for Independence

Author(s): Susan L. Swan

Source: Environmental Review: ER, Vol. 6, No. 1 (Spring, 1982), pp. 54-62

Published by: Forest History Society and American Society for Environmental History

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3984049 .

Accessed: 17/06/2014 15:13

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Forest History Society and American Society for Environmental History are collaborating with JSTOR to

digitize, preserve and extend access to Environmental Review: ER.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 15:13:57 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and

Mexico's Struggle

for

Independence

Susan L. Swan

Washington State University

In an agricultural economy, perhaps no other environmental factor is

of such concern as bad weather. Problems like poor soil, pests, para-

sites, and diseases can often be related to weather conditions. How

directly can human events be related to weather?

For some researchers, the connection is direct. H. H. Lamb, for

example, links Viking colonization of Iceland, Greenland, and North

America with a warming trend from A.D. 400-1200, a trend that peaked

about A.D. 800-1000. On the other hand, E. L. Ladurie is more cau-

tious regarding the influence of weather on human events and doubts,

for example, whether meteorological conditions during the "Little

Ice Age" (circa 1590-1850) had significant impact on agriculture in

Europe.1

Nevertheless, there are places and times in history when the

temptation to link weather conditions and human events is strong.

One such period is the early years of struggle for Mexico's indepen-

dence. As in other Latin American countries, revolution broke out in

54

Mexico at the end of the first decade of the nineteenth century.

Elsewhere, however, the struggle for independence was led by

American-born upper-class Creoles. But in Mexico, although the ini-

tial movement was led by a middle class Creole priest, Miguel Hidalgo

y Costilla, it soon took on the tones of class warfare. The result

was that Mexico's Creoles turned against the revolution and helped

delay independence for a decade, until 1821. Father Hidalgo could

count on only fourteen workers from his pottery factory and thirty-

one soldiers from the local Regiment of the Queen. The question,

then, is why this modest beginning exploded into an army of 80,000

proverty-stricken Indians.2 Without those untidy, illiterate

peasants, the Hidalgo revolt would have remained a mere incident

relegated to an historical footnote. Why, then, did the masses rise?

In response to revolutionary rhetoric? To follow Hidalgo's charisma-

tic leadership? In class hatred against the Spaniard? Probably none

of these was as much a factor as something far more prosaic: the

weather.

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 15:13:57 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

This theory is not new. In the late 1960s, Mexican economic

historian Enrique Florescano suggested that the revolution for inde-

pendence began as a result of a sustained thirty-year increase in

the price of maize, which meant also an increase in the price of

other cereals and of meat. Florescano arrived at this hypothesis by

graphing maize prices from 1708-1810. Comparing his graphs with

those of William Beveridge for European wheat prices -- graphs which

Beveridge connected with European weather conditions -- Florescano

was able to assess the impact of weather conditions in Mexico. He

proposed that the revolutionary outbreak of 1810 was in response to

an agricultural crisis caused by severe droughts in 1808 and 1809,

the latter of which affected nearly all of Mexico's cereal-producing

zones.3

Unfortunately, weather data are limited for colonial Mexico. 4

Where weather data are available for the period, they support the

thesis that weather conditions affected Mexico's revolutionary move-

ment. This is true, for example, of documents pertaining to the

hacienda of Tulancalco. Letters between the property's administrator

and its owners indicate that there was drought from 1808 to 1811 in

north central Mexico. 5

Another reason this material is significant is because it is

doubtful whether economic hardship spread over a generation, as

Florescano proposed, could spark revolution. Rather, a sudden econo-

mic disaster over a three or four-year period would incite rebellion.

What happened in 1810 was that a very minor revolt, which might other-

wise have been quickly forgotten, became a major conflagration due to

the desperation of hungry men. And chronic dissatisfaction with their

lot on the part of the masses, which might otherwise have produced no

more than scattered food riots, found focus in the revolutionary

rhetoric of Miguel Hidalgo. The marriage of the two resulted in the

opening guns of Mexico's struggle for independence, but had it not

been for severe drought from 1808-1811, those cannons may have been

no more than popguns.

Data from the hacienda of Tulancalco underscore this, for the

property itself lay within the area of revolutionary violence.

Located in the semiarid to arid Mezquital near the town of Actopan in

Hidalgo state, Tulancalco was chronically short of water. Neverthe-

less the hacienda yielded a variety of staples, such as maize, barley,

turnips, and frijoles. But the mainstay of the hacienda was maguey,

the plant used to produce the intoxicant, pulque. Livestock produc-

tion consisted of sheep, horses, burros, mules, and goats. 55

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 15:13:57 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

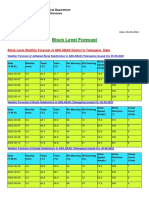

Although drought was chronic at Tulancalco, the situation

worsened when the rainy season changed about 1808. The wet season not

only came a bit earlier, probably foiling established planting customs,

but even worse, was shorter as well. For example, from 1799 to 1808,

the rainy season was generally from late May to the end of August,

with most precipitation falling from mid-June until the end of August

and continuing, at a lesser pace (at least through 1803), into Novem-

ber. After 1808, however, the rains began in mid-April and ended by

the end of August, if not before. Significantly, in 1810 nearly a

month of drought separated the bit of rain that fell in mid-June,

mid-July, and mid-August, traditionally the wettest months of the year.

Not surprisingly, just as the rainfall pattern shifted at Tulan-

calco, so did that for drought. Basically, the rainy season decreased

in duration, as noted above, and drought correspondingly increased.

With rain coming earlier, in mid-April, May became dry. The years

from 1808 to 1811 were particularly bad ones, with dryness from early

May through August. Prior to this, dryness during the rainy season

was more likely from mid-May to mid-August. Thus the period during

which drought interrupted the wet season increased a half-month at

each end from 1808 to 1811 and, worse, was more continuous as well.

(Again, it should be kept in mind that this dryness was during the

growing season, usually the wetter season of the year.) That the

drought years from 1808 to 1811 were ones of acute agricultural hard-

ship, both for crops and livestock, is painfully clear from the haci-

enda manager's letters.

The impact of drought can be surmised from the fact that, with-

out irrigation, rainfall in Mexico's highlands is sufficient for only

a single annual crop during the summer. Crops destroyed by bad

weather cannot be replaced.

Tulancalco's crops suffered throughout the first decade of the

nineteenth century, with the months of May, June, July, August, and

October almost uniformly bad. The greatest problem was drought, par-

ticularly from 1808 to 1811. All crops on the hacienda suffered,

including the property's mainstay, maguey. Although maguey is highly

drought resistant, conditions became so severe that they retarded the

flow of sap from which pulque is made. Compounding the problem was

the fact that, due to the failure of the area's maize crops, there

were no buyers for the pulque that was produced. Due to price

increases, however, Tulancalco's pulque revenues did not significantly

decline. Instead, the area's masses were deprived of what little

56 solace existed in a desperate time.6

But bad weather conditions affected livestock as well. Dryness

meant starvation, disease, and ultimately for many, death due to their

weakened condition. Worse, increased livestock mortality was accom-

panied by a failure to maintain an adequate birthrate. Thirst-weakened

females aborted, gave stillbirth, produced offspring too weak to

survive, or were unable to produce sufficient milk for their young.7

Of all Tulancalco's lifestock, sheep were most susceptible to

drought. Prior to 1808 sheep losses occurred due to drought. In July

1804, the hacienda's owner noted a decrease of 495 sheep. These

losses were expected to be overcome through lambing, but during the

following May, drought caused the deaths of 300 additional head. The

problem was chronic, for in May 1807, the hacienda's manager reported

that the sheep were dying from starvation. The only remedy was rain

to make the pastures green. In April 1807, ninety-three sheep died.

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 15:13:57 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The situation did not improve in 1808 when in two categories of sheep

alone (new lambs and those recently castrated), 227 head were lost.8

The year 1808 marked the beginning of the especially severe three-

year drought. During this period Tulancalco's sheep losses increased.

By August of 1810, for example, the mortality for the year was 715

sheep of all categories. In March 1811, the manager reported an inven-

tory of 2026 head as compared to the 2537 head he had reported for

March, 1810.9

As might be expected in an agricultural economy, these losses

in crops and livestock had an impact on people as well. Not only was

there a shortage of food, but the price of the food that was avail-

able rose. When transport animals like mules died or became too

weak to carry grains to market, carting fees went up. Enrique Flores-

cano noted that in 1779 and 1788, freight charges increased fifty

per cent.10 Moreover, losses in one grain crop meant that others

would rise in price as well.11

Unfortunately, these phenomena were not mere quirks of the

market, but a stable pattern. As Florescano pointed out, each year,

soon after harvest, prices would be low as the small operators sold

their crops. As this supply diminished in the spring, the large

landholders would move into the market with their high-priced re-

serves. The result, especially in years of shortages was disease,

theft, begging and vagrancy.12

A pattern existed of selling in time of plenty and of hoarding

in time of scarcity. In November, 1803, with fair weather, Tulan-

calco's owners directed its manaqer to sell maize. Instructions were

the same when weather was good in July 1805.13 This marketing philo-

sophy supports Florescano's belief that the Mexican revolution in

1810 was a result of a sustained thirty-year increase in the price

of maize, which meant also an increase in the price of other cereals

and of meat.14

57

Indeed, the manager's letters from Tulancalco vividly depict the

social unrest that resulted from the agricultural shortages during

these years. As early as October, 1809, he informed the owning family

that the Indians from the communities of the area were rustling live-

stock. As of that date, they had stolen sixteen cows and four bulls.

In May, 1810, the manager again complained about Indians stealing

cattle, not only on Tulancalco but on all the haciendas in the area.

Although some had been caught and punished severely, the problem

continued. While he acknowledged that there was poverty in the area,

he maintained that the Indians were so corrupt that they did not want

to work. A week later he evidently had been able to reduce Tulan-

calco's losses from thievery, but he noted that even though the jails

were full of Indians, they did not seem to learn from experience.15

Then, on 4 August 1810, less than a month and a half before the

outbreak of hostilities, the manager wrote:

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 15:13:57 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

181o

1809 l__

1808B

1807

1806

1805

1804

1803

1802

1801

1800

1799

5 10 15 20 25 30 5 10 15 20 25 5 10 15 20 2530

JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH

- DROUGHT DROUGHT AD IL

- ~FROST DROUGHT AND SNOWC SNOW

1811 IX

-1810. l Xl i <

1809 _

1808

1807

1806

1805

1804

58

1803

1802

1801

D

1799 _lD0

5 10 15 25 30 5 |10 15 30 5 10 15 20 25

201 20A 251 130

APRIL MAY JUNE

DROUGHT DROUGHT AND FROS HAIL

S D_ -H

ERS DRUH-N SNOi E l |

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 15:13:57 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1811

1810

1809 X XX DocD<

1808 D<x XD X X X / 8

1807

1806

1805

1804

1803

1802 XX

1801

1800

1799 = I

5 10 15 20 25 30 5 10 15 20 25 30 5 10 15 20 25 30

JULY AUGUST SEPTEMBER

DROUGHT DROUGHT AND FROST HAI

FROST DROUGHT AND SNO SNOW

1811

1l810 '9 A I I 11 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1'

1809

1808

1807

1806

.1805

1804

59

1803

1802

1801

1800

1799

5 10 15 20 25 30 5 10 115 20 25 30 5 10

l 15 20 25 30

OCTOBER NOVEMBR DECEMER

DROUGHT DDROUGHT AND FROST HaIL

FROST DROUGHT AND SNOW SNOW

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 15:13:57 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

.. nowadays there is such necessity among the Poor People

that they cannot find anything to Eat, and the Indians from

these villages are robbing cattle even in broad daylight;

this is General on all these Haciendas ... since on the one

hand they are caring for the Livestock, and on the other

they are robbing by day and by Night.16

It was, unfortunately, at this time that he decided to collect the

back rents and debts of his tenants and workers. Although he was

unsuccessful, his attempt to do so in a time of great economic

necessity aggravated hacienda-employee relations. Since other

hacienda owners in the area were probably pursuing similar policies,

it is little wonder that the Indians, suffering conditions of famine,

found the situation unbearable.17

Unfortunately, the social and economic dislocations caused by

the revolutionary activity in the area made matters no better. On

15 September 1811, the manager wrote that, due to their great distress,

the Indians were even venturing into the corrals by night to steal

sheep and cattle. Tulancalco's cowboys captured two rustlers. When

they took the thieves to the jail at Actopan, they found it full.18

Yet, during the period covered by the manager's letters, insur-

gents rarely visited Tulancalco. Violence did occur at other hacien-

das in the area, so he moved his family to Aetopan. This was fortu-

nate, for in December, 1811, there was a skirmish at Tulancalco

involving the insurgents.

What this indicates is that, even before the outbreak of violence

in the area about Tulancalco, there was considerable social unrest due

to food shortages caused by the drought from 1808 to 1811. It took

only Hidalgo's small spark to fire this unrest into a blaze of revolu-

tionary violence. To conclude, then, there is considerable reason to

believe that meteorological inclemency had much to do with the Revolu-

tion of 1810, if not in its origin, then certainly in its scope and

intensity -- that, indeed, there was a link between weather and poli-

tics that helped shape Mexico' s struggle for independence.

60 ENDNOTES

1H(ubert) H. Lamb, The Changing Climate (London: Methuen & Co.,

Ltd., 1966), pp. 4-12; Emmanuel LeRoy Ladurie, Times of Feast, Times

of Famine (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Conpany, Inc., 1971),

p. 243.

2Hugh H. Hamill, Jr., The Hidalgo Revolt: Prelude to Mexican

Independence. (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1966), pp.

119, 183.

3Enrique Florescano, Precios del maiz y crisis agricolas en

Mexico (1708-1810) (Mexico: El Colegio de Mexico, 1969), pp. 120-24,

129, 144, 148, 179, 195.

4Charles Gibson, The Aztecs Under Spanish Rule (Stanford:

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 15:13:57 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stanford University Press, 1964), p. 303; Jorge A. Vivo' Escoto,

"Weather and Climate of Mexico and Central America," in Robert

Wauschope, gen. ed., Handbook of Middle American Indians, Vol. 1:

Natural Environment and Early Cultures (Austin: University of Texas

Press, 1964), p. 187.

5These documents are part of the manuscript collection known as

the Regla Paper, hereafter referred to as RP, which reside in the

Archives Division of the Washington State University Library in

Pullman, Washington. The letters regarding Tulancalco were sent

between the hacienda administrator, Manuel Olguin, hereafter referred

to as Olguin, and a member of the owning family, Marfa Josefa Velasco

y Ovando, hereafter referred to as Maria Josefa. The documents are

organized by folders (F) and, when paginated, verso is indicated by

V.

6Maria Josefa to Olguin, 10 June 1801, RP, F123, p. 46v; 2 May

1804, RP, F127, p. 6v; 3 Oct. 1804, RP, F127, p. 16; 10 July 1805,

RP, F129, p. 7v; 11 Sept. 1805, FP, F129, p. lOv; 2 Oct. 1805, RP,

F129, p. llv; 25 June 1806, RP, F132, p. llv; Olguin to Maria Josefa,

27 Jan. 1810, 11 July 1810, 14 July 1810, 4 Aug. 1810, and 6 Oct. 1810,

RP. F141; 13 July 1811, RP, F143.

70g/

701guin to Maria Josefa, 20 Oct. 1810, RP, F141.

8Maria Josefa to Olguin, 4 July 1804, RP, F127, p. 10; 29 May

1805, RP, F125, p. 5; Olguin to Maria Josefa, 22 May 1807, and 10 May

1807, RP, F134; 7 Jan. 1809, RP, F138.

9oiguin to Maria Josefa, 4 Aug. 1810, RP, F141; 9 Mar. 1811 and

31 Aug. 1811, RP, F143.

'OFlorescano, p. 148.

l"Evidence for these assertions comes from Regla documents con-

cerning other haciendas, as stated in the following correspondence:

Marcos Morales to Mariano de Velasco, 8 Feb. 1778, RP, F86; 15 Apr.

178r, RP, F101; Maria Josefa to Juan Vicente Berazain, 4 May 1799,

RP, F118, p. 30; Maria Josefa to Jose Cristoval Truxillo, 14 Feb.

1801, RP, F123, p. 17v.

12Florescano, pp. 92-93, 150-72.

l3Maria Josefa to Olguin, 2 Nov. 1803, RP, F125, p. 23y; 24 July 61

1805, RP, F129, p. 8. Elsewhere in the Regla Papers, Maria Josefa

instructs managers of other haciendas to hoard in time of bad weather:

Maria Josefa to Jose Cristoval Truxillo, 10 Oct. 1801, RP, F123,

p. 75v; 12 Dec. 1801, RP, F123, p. 97; 10 July 1802, RP, F124, pp.

56v-57.

14Florescano, pp. 129, 144, 148, 179, 195.

1501guin to Maria Josefa, 21 Oct. 1809, RP, F138; 18 May 1810 and

26 May 1810, RP, F141.

161 ..en el dia es mucha nesesidad que hay en estas Pobres Jentes

pues no encuentran ni para Comer, y los Yndios de estos Pueblos aun

de dia claro estan rrobando reses esto es General en todas estas Has.

das . .. pues por un lado se estan cuydando los Ganados, y por otro estan

rrobando esto es de dia y de Noche." Olguin to Maria Josefa, 4 Aug.

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 15:13:57 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1810, RP, F141.

/

17

170lguin to Maria Josefa, 14 July 1810, 4 Aug. 1810, and 3 Sept.

1810, RP, F143.

l801guin to Maria Josefa, 5 Sept. 1811, 16 Nov. 1811, and 7 Dec.

1811, RP, F143.

62

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.55 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 15:13:57 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Book Review: CAB International 2005Document3 pagesBook Review: CAB International 2005Macarena Furque0% (1)

- Summary of Why The West Rules For NowDocument5 pagesSummary of Why The West Rules For NowKen Padmi100% (1)

- ETOPS BriefingDocument50 pagesETOPS Briefingshohimi harunNo ratings yet

- Great FamineDocument30 pagesGreat FamineGossa100% (1)

- Mexicans at War: Mexican Military Aviation in the Second World War, 1941–1945From EverandMexicans at War: Mexican Military Aviation in the Second World War, 1941–1945No ratings yet

- Quick Test 2: Grammar Tick (Document3 pagesQuick Test 2: Grammar Tick (Silvina CaceresNo ratings yet

- A Victorian Holocaust: Iran in the Great Famine of 1869–1873From EverandA Victorian Holocaust: Iran in the Great Famine of 1869–1873Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- British History in the Nineteenth Century (1782-1901) (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)From EverandBritish History in the Nineteenth Century (1782-1901) (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- The Gothic Novel PDFDocument12 pagesThe Gothic Novel PDFWasanH.Ibrahim100% (2)

- Megadrought and Megadeath in 16th Century MexicoDocument3 pagesMegadrought and Megadeath in 16th Century MexicoJorge HorbathNo ratings yet

- Global Crisis 25-10Document3 pagesGlobal Crisis 25-10luciagabriela.theoktisto01No ratings yet

- Chloroanaemia Lab ReportDocument2 pagesChloroanaemia Lab ReportGeovani OlivaresNo ratings yet

- Cources Work OneDocument14 pagesCources Work OneAssumptaNo ratings yet

- Ssush7 NotesDocument8 pagesSsush7 Notesapi-295848629No ratings yet

- McFARLANE Rebellions in Late Colonial Spanish AmericaDocument27 pagesMcFARLANE Rebellions in Late Colonial Spanish AmericagregalonsoNo ratings yet

- 02 - Agrarian SocietyDocument5 pages02 - Agrarian SocietyEmanuele Giuseppe ScichiloneNo ratings yet

- History CA AgricultureDocument15 pagesHistory CA AgricultureThy TranNo ratings yet

- Inflation and DearthDocument9 pagesInflation and Dearthisabel teixeiraNo ratings yet

- AP Euro Notes - France Austria WarDocument10 pagesAP Euro Notes - France Austria WarjoeyNo ratings yet

- Britain and AmericaDocument5 pagesBritain and AmericaSandraNo ratings yet

- The Little Ice Age ThesisDocument8 pagesThe Little Ice Age Thesisfjmayw0n100% (1)

- French Revolution (1789-1799)Document21 pagesFrench Revolution (1789-1799)anushkamahipal2No ratings yet

- Chapitre 5 Georgian England and The 18th CenturyDocument3 pagesChapitre 5 Georgian England and The 18th CenturyLeïla PendragonNo ratings yet

- Feudal Europe Bourgeoisie Peasants Standard of Living Education Feudalism Standards of Living MortalityDocument2 pagesFeudal Europe Bourgeoisie Peasants Standard of Living Education Feudalism Standards of Living MortalityniqqazNo ratings yet

- Depression EraDocument1 pageDepression Eraapi-721514762No ratings yet

- Activity Sheet World History 2Document9 pagesActivity Sheet World History 2Rechelle LabianNo ratings yet

- 02 Readings 6Document5 pages02 Readings 6Anjanette TenorioNo ratings yet

- 17th Cen CrisisDocument3 pages17th Cen CrisisShivangi Kumari -Connecting Fashion With HistoryNo ratings yet

- Mexico's Environmental Collapse and AmericaDocument48 pagesMexico's Environmental Collapse and AmericaGiles SladeNo ratings yet

- Angliski Proektna ZadacaDocument14 pagesAngliski Proektna ZadacapetreNo ratings yet

- ASSIGNMEN4Document4 pagesASSIGNMEN4Muhammad SaqlainNo ratings yet

- A Farewell To Alms Clark en 9377.simpleDocument10 pagesA Farewell To Alms Clark en 9377.simpleNathan LaingNo ratings yet

- Bedrite AnalysisDocument2 pagesBedrite AnalysisNato üNo ratings yet

- Dust Bowl DocumentsDocument2 pagesDust Bowl DocumentsAlec BandaNo ratings yet

- Coolturita IIDocument174 pagesCoolturita IINehuén D'AdamNo ratings yet

- Cocoliztli EssayDocument3 pagesCocoliztli EssayIsaac AlcaláNo ratings yet

- Civilazation and Capitalism 15th-18th Century. Volume 1 - Fernand Braudel - 0051Document1 pageCivilazation and Capitalism 15th-18th Century. Volume 1 - Fernand Braudel - 0051Sang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- Romantic PeriodDocument4 pagesRomantic PeriodAbinaya RNo ratings yet

- Q1Document8 pagesQ1Aishvarya MishraNo ratings yet

- The Crisis of The Seventeenth Century The Little Ice Age and The Mystery of The Great Divergence - Jan de VriesDocument10 pagesThe Crisis of The Seventeenth Century The Little Ice Age and The Mystery of The Great Divergence - Jan de VriesGustavo LemeNo ratings yet

- Nonrepudiable DiagramDocument2 pagesNonrepudiable Diagramadus9001No ratings yet

- Mexico HistoryDocument12 pagesMexico HistoryAlma MusaNo ratings yet

- WordsworthDocument43 pagesWordsworthQamar Abbas ShahNo ratings yet

- Project On 18-19th Century ChangesDocument19 pagesProject On 18-19th Century ChangesAli HusainNo ratings yet

- 14th Century - Crisis of The Late Middle AgesDocument4 pages14th Century - Crisis of The Late Middle AgesJean-pierre NegreNo ratings yet

- The Secret History of Natural DisasterDocument6 pagesThe Secret History of Natural DisasterPame AguirreNo ratings yet

- Tema 5Document5 pagesTema 5ireeNo ratings yet

- Social and Political Legacies of Emancipation of Slavery in The AmericaslDocument28 pagesSocial and Political Legacies of Emancipation of Slavery in The Americaslbertha josephNo ratings yet

- The Rise and Fall of CivilisationsDocument3 pagesThe Rise and Fall of CivilisationsFélix BonillaNo ratings yet

- c.1. The Victorian Age - IntroductionDocument6 pagesc.1. The Victorian Age - IntroductionMazilu Adelina100% (1)

- 1 The Novel in Its Context: ObjectivesDocument10 pages1 The Novel in Its Context: ObjectivesmaayeraNo ratings yet

- The 17th Century Crises in EuropeDocument7 pagesThe 17th Century Crises in Europeakku UshaaNo ratings yet

- Rebellions in Late Colonial Spanish AmerDocument26 pagesRebellions in Late Colonial Spanish AmerRossana BarraganNo ratings yet

- Economic Decline in Europe During The Fourteenth CenturyDocument5 pagesEconomic Decline in Europe During The Fourteenth CenturyDavid ZhaoNo ratings yet

- 17 TH Century Crisis in Europe - The DebaDocument20 pages17 TH Century Crisis in Europe - The DebaSamridhi AhujaNo ratings yet

- 1-Tomich Zeuske Intro 2nd Slavery Mass Slavery World Econ Comp MicrohistoriesDocument11 pages1-Tomich Zeuske Intro 2nd Slavery Mass Slavery World Econ Comp MicrohistoriesSebastião De Castro JuniorNo ratings yet

- Causes of 17th Century Crisis in EuropeDocument6 pagesCauses of 17th Century Crisis in EuropeKashish RajputNo ratings yet

- Overglanced AnalysisDocument2 pagesOverglanced AnalysisDIEGO ANDRES VERA SALAZARNo ratings yet

- Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History: CloseDocument21 pagesOxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History: CloseemiroheNo ratings yet

- Journal of Political EconomyDocument19 pagesJournal of Political Economyaung zaw uNo ratings yet

- The Republic of Indians in Revolt c.168 PDFDocument58 pagesThe Republic of Indians in Revolt c.168 PDFGiovanni VidoriNo ratings yet

- Paraguayan Independence and Doctor FranciaDocument23 pagesParaguayan Independence and Doctor FranciaFederico YouNo ratings yet

- WIDGB3 Utest Skills 2BDocument2 pagesWIDGB3 Utest Skills 2BGumbNo ratings yet

- U6-Writing-HW - ReviewedDocument6 pagesU6-Writing-HW - ReviewednuongtranNo ratings yet

- You Can Type Something HereDocument31 pagesYou Can Type Something HereLilibethNo ratings yet

- HYDROMETEOROLOGY - Introduction To Meteorology - RiveraDocument5 pagesHYDROMETEOROLOGY - Introduction To Meteorology - RiveraArman RiveraNo ratings yet

- Asd BlocklevelfrctDocument45 pagesAsd BlocklevelfrctSri SravaniNo ratings yet

- Week 1 Origin and Structures of The EarthDocument2 pagesWeek 1 Origin and Structures of The EarthDesiree UrsulumNo ratings yet

- 7A Q1 L9 (1) - Trang-1-4Document4 pages7A Q1 L9 (1) - Trang-1-4Minh Phạm NgọcNo ratings yet

- CBSE Class 9 Geography Chapter 1 Notes - Size and LocationDocument4 pagesCBSE Class 9 Geography Chapter 1 Notes - Size and LocationHarsh PalNo ratings yet

- Vijayawada Dharmapuri Pipeline Project: WorleyparsonsDocument3 pagesVijayawada Dharmapuri Pipeline Project: WorleyparsonsAnish AnGo GoswamiNo ratings yet

- Site Analysis (Alindahaw Lakeview Resort)Document2 pagesSite Analysis (Alindahaw Lakeview Resort)Viberlie PonterasNo ratings yet

- Summit LearningDocument4 pagesSummit Learningbushrawork1997No ratings yet

- Climate - WeatherDocument41 pagesClimate - WeatherHamza MujahidNo ratings yet

- B2 First Listening Test 11Document3 pagesB2 First Listening Test 11Edgar SchultzNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0305748822000524 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S0305748822000524 MainShijie YE (Eric)No ratings yet

- Wider World 3 LanguageTest U 2 Group BDocument4 pagesWider World 3 LanguageTest U 2 Group BАнастасія ЮндаNo ratings yet

- Amrita PGDM 34Document1 pageAmrita PGDM 34Rashmi UtagiNo ratings yet

- Unit 5: Worksheet 7Document1 pageUnit 5: Worksheet 7Marta VelvettaNo ratings yet

- ĐỀ THI CUỐI HỌC KỲ II ANH 8Document4 pagesĐỀ THI CUỐI HỌC KỲ II ANH 8Hà Trang NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Tech Note 7B (Nov 2017)Document10 pagesTech Note 7B (Nov 2017)tonyNo ratings yet

- English6 q4 Week1 v4Document8 pagesEnglish6 q4 Week1 v4Corazon Diong Sugabo-TaculodNo ratings yet

- Geography Worksheet¬esDocument44 pagesGeography Worksheet¬esCanttell SpookehNo ratings yet

- Antarctica - Coldest and Least Friendly Place On EarthDocument27 pagesAntarctica - Coldest and Least Friendly Place On EarthLorena StamariaNo ratings yet

- AT #3 - Sci2 BY PAIR: JOCSON, John Lloyd KAHULUGAN, Elaisha EDocument3 pagesAT #3 - Sci2 BY PAIR: JOCSON, John Lloyd KAHULUGAN, Elaisha EBryll Joshua PinoNo ratings yet

- Science Weather Lesson Plans 1Document2 pagesScience Weather Lesson Plans 1api-686591351No ratings yet

- Hazard Assessment 3Document5 pagesHazard Assessment 3Arnel Bautista ArregladoNo ratings yet

- Effects SettingsDocument56 pagesEffects SettingsHanifan EngranoNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Caraga Region Schools Division of Surigao Del SurDocument3 pagesDepartment of Education: Caraga Region Schools Division of Surigao Del Surnoel bandaNo ratings yet

- DLL - Science 6 - Q4 - W3Document12 pagesDLL - Science 6 - Q4 - W3JannahNo ratings yet