Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Reading Cheng Chwee

Uploaded by

edithbjCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Reading Cheng Chwee

Uploaded by

edithbjCopyright:

Available Formats

The Essence of Hedging: Malaysia and Singapore's Response to a Rising China

Author(s): KUIK CHENG-CHWEE

Source: Contemporary Southeast Asia , August 2008, Vol. 30, No. 2 (August 2008), pp.

159-185

Published by: ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41220503

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41220503?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Contemporary Southeast Asia

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Contemporary Southeast Asia Vol. 30, No. 2 (2008), pp. 159-85 DOI: ЮЛЗбб/сзЗО-га

© 2008 ISEAS ISSN 0219-797X print / ISSN 1793-284X electronic

The Essence of Hedging:

Malaysia and Singapore's

Response to a Rising Ch

KUIK CHENG-CHWEE

Recent International Relations scholarships and policy publications

have used the term "hedging" as an alternative to "balancing" and

"bandwagoning" in describing small states' strategies towards a rising

power. In the case of Southeast Asian countries' responses to a re-

emerging China, more and more analysts have asserted that none of

the smaller states are pursuing balancing or bandwagoning in the strict

sense of the terms, and that the states are in fact adopting a "middle"

position that is best described as "hedging". This paper seeks to assess

this assertion by performing three principal tasks. First, it attempts

to identify the key defining attributes and functions of hedging as

a strategy that is distinguishable from pure forms of balancing and

bandwagoning. Second, it aims to operationalize the term within the

context of Southeast Asia-China relations, by focusing on the cases of

Malaysia and Singapore's response to China in the post-Cold War era.

Third and finally, the study explains why these two states have chosen

to hedge in the way they do. The central argument of the essay is that

the substance of the two smaller states' policies are not determined by

their concerns over the growth of China's relative power per se; rather,

it is a function of regime legitimation through which the ruling elite

seek to capitalize on the dynamics of the rising power for the ultimate

goal of justifying their own political authority at home.

Keywords: Hedging, balancing-band wagoning, regime legitimation, small-

behaviour, Southeast Asia-China relations.

Kuik Cheng-Chwee is a Lecturer in International Relations at the National

University of Malaysia (UKM), and concurrently a Ph.D. candidate at

Johns Hopkins SAIS, Washington, D.C.

159

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

160 Kuik Cheng-Chwee

What do states do when f

potentially threatening G

International Relations (IR) t

to this central question: st

bandwagon with that power

to preserve their own secu

- tend to perceive a rising

counter-checked by allian

(internal balancing).2 This

aggregate capability is ac

offensive capability and o

school, by contrast, opines

rather than contain against

come to accept a subordina

for profit.4 This may happen

of strength that can be expl

Notwithstanding the en

thought, recent scholarly

propositions might not a

Asian states to a rising C

indicate that the regional s

or bandwagoning. While

some form of military tie

United States), these effort

strategy in its strictest se

cooperation actually pred

clear indication that the st

have been primarily stimu

the growth of China's rela

In a similar vein, while East Asian states have all chosen to

develop economic ties and to engage China diplomatically, this gesture

should not be confused as bandwagoning. Economic cooperation

and diplomatic engagement are chiefly motivated by a pragmatic

incentive to gain economic and diplomatic profit; by themselves they

do not constitute an act of power acceptance.8 Bandwagoning, by

contrast, reflects a readiness on the part of smaller states to accept

- voluntarily or otherwise - the larger partner's power ascendancy;

and such power acceptance often take the forms of political and

military alignment. Empirically, however, none of the regional states

have forged security alliances with China.

A range of factors explain why most regional states have rejected

pure-balancing and pure-bandwagoning. Pure-balancing is considered

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Essence of Hedging 161

strategically unnecessary, because

potential rather than actual. It is a

and counter-productive, in that an

push China in a hostile direction,

a real one. Further, it is regard

is likely to result in the loss of t

reaped from China's growing mar

other hand, albeit economically

undesirable and strategically ris

smaller states' freedom of action.

For these reasons, most of the East Asian states do not regard

pure-balancing and pure-bandwagoning as viable options vis-à-v

China. In the case of the original members of the Association o

Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), none of the countries have

chosen to contain against or crouch under China in the post-Cold

War era. Instead, they have taken a middle position that is now

widely termed as the "hedging" strategy.9 Borrowed originally from

finance, the term is brought into IR to refer to an alternative strategy

distinguishable from balancing and bandwagoning. It has been used

not only to describe small-state reactions to power ascendancy, but

also big-power strategies.

This article examines the former, focusing on the cases of

Malaysia and Singapore's response to the rise of China in the post-

Cold War era, specifically, from 1990-2005. It seeks to explore the

notion of hedging as an alternative analytical tool to identify the

substance and differences of small-state behaviour in the face of

power asymmetries. Ultimately, it aims to explain why the smaller

states have responded to a rising power in the way they have.

The main argument of the paper is that a small state's strategy

towards a rising power is driven not so much by the growth of

the Great Power's relative capabilities per se; rather, it is motivated

more by an internal process of regime legitimation in which the

ruling elite evaluate - and then utilize - the opportunities and

challenges of the rising power for their ultimate goal of consolidating

their authority to govern at home. This argument - which may be

termed the Regime Legitimation (RL) framework - is premised on

three core assumptions. First, foreign policy choices are made by

ruling elites, who are concerned primarily with their own political

survival. As such, their policy actions are geared towards mitigating

all forms of risks - security, economic and political - that may

affect their governance capacity. Second, the representation of risks

- which risks will be identified and prioritized as foreign policy

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

162 Kuik Cheng-Chwee

"problems" - is neither gi

by the way in which elit

acting in accordance with t

a given time. Third, such

compliance with liberal-de

preserve security and inter

to uphold sovereignty an

peculiar to a particular c

with vulnerability", the ne

It is within the context of

ramification of a rising p

This set of assumptions

mainstream neo-realist tradi

ing premises. First, states

who seek their own securi

tend to rely on military f

behaviour is driven chiefl

across units, rather than sta

hold true, then we should

of power - in this case, an

- will cause the small sta

turn, will compel them to

capabilities for balancing

their security.

On the other hand, if t

should expect that a gro

not necessarily have an in

whether or not the struct

smaller states, it will depe

perceive the power as a boo

All things being equal, in

Power is perceived to be

the power's growing ascen

the Great Power's growing

legitimation, the state is e

instances in which the ram

to be mixed or unclear, th

intricate approach, the s

ordering of the elite's leg

if the elite's current legi

of prosperity-maximizing

expected to highlight econ

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Essence of Hedging 163

tapped from the power, while

it may have about the giant.

The remainder of the paper i

first section provides a working

its antecedent conditions. The s

into five components along the

as a way to measure the range

Next, on the basis of the ident

takes an empirical look by deta

policies. The final section concl

strengths of neo-realism and R

variation in the two strategies.

Defining "Hedging"

The term "hedging" is defined

country seeks to offset risks b

that are intended to produce mu

the situation of high-uncertaint

The notion of "risks" is a ke

human behaviour, either in agricu

In the realm of international p

three major genres: security,

of these risks (e.g. military agg

are originated from intentional

actors, others are products of im

global economic downturns, dom

changes in the distribution of

these risks are especially harmf

the states' internal limitation t

and in part because they lack re

and to mitigate the risks by th

In this regard, Great Powers o

or otherwise - in a small state's risk management. Their roles,

however, are far from unidirectional. On the one hand, a big power

may throw its weight behind the state's elite and provide them with

the needed resources to mitigate certain risks, such as a looming

military threat or an enduring economic hardship. On the other

hand, a Great Power may harm smaller states in every conceivable

way. It may turn its might into a "right" to impose its will on

actors within its "sphere of influence", or it may invade them for

resources or political domination.

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

164 Kuik Cheng'Chwee

Given the Great Powers'

mitigation efforts, an ag

weak states is thus: how s

Powers, in a way that w

simultaneously cushionin

stronger powers? Should

something else?

Fundamentally, the ma

to accept, accommodate

well as the manner in which it would approach other actors

(other powers, neighbouring countries, etc) to strengthen its position

- is largely dependent on whether it is faced with ал imminent

security threat In cases where a state comes to view a particular

actor as an immediate threat, the state is likely to pursue a

balancing strategy vis-à-vis the actor: its strategic assets will be

mobilized for security-seeking ends. Conversely, in cases where a

state views an actor not as a threat but a principal source of aid,

then it is likely to opt for bandwagoning: profit-seeking behaviour

will prevail.

More often, however, there are circumstances where elites do

not perceive any imminent and unambiguous threat. Instead, they

may view the embodiments of risks to be more versatile,

multifaceted and uncertain. This is a situation many countries in

the Asia Pacific have found themselves in post-Cold War. While the

collapse of the socialist bloc effectively ended the decades-long

East-West confrontation, the abrupt disappearance of bipolarity

engendered a deep sense of uncertainty among regional countries,

particularly the smaller ASEAN states.13 Following the reduction

of superpower military presence in Southeast Asia, uncertainties

have revolved around whether, and to what extent: (a) the United

States will scale down its force structure in the region; (b) the

Asian powers of China, Japan and India will compete to fill in the

"power vacuum"; and (c) ASEAN will remain relevant in the new

regional environment.14

In part due to the uncertain regional order, and in part due

to the double-edged role of Great Powers, the smaller states can

no longer afford to develop too close or too distant a relationship

with any of the major powers. This is because getting too close to a

colossus may entail the possibility of losing their independence and

inviting uncalled-for interference, which, in turn, may undermine

the elites' legitimacy in the eyes of their constituencies. Worse,

it may unnecessarily drag the states into potential Great Power

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Essence of Hedging 165

conflict, leaving them with t

the wrong horse". On the oth

from a Gulliver may cost the e

sort of benefits that can be util

standing. Worse, it may arouse

Gulliver, thus putting the state

Great Power gains pre-eminence

high for small states to adopt th

and evolving power structure.

The problem for small states i

power structure will fluctuate a

for them to ascertain how and when this will occur. This is because

the distribution of power is a systemic process that cannot be

controlled by any single actor, and because the commitment of

a Great Power is always open to change, as painfully learned by

ASEAN elites in the wake of the British "East of Suez" policy and

the Nixon Doctrine in the late 1960s. Given the uncertainties and

the stakes involved, small states would always have a tendency to

hedge, and to avoid taking sides or speculating about the future of

Great Power relations.

Whether such a tendency will be actualized as a behaviour,

however, is contingent on many factors. Three factors stand out: (a) the

absence of an immediate threat (that might compel a state to ally with

a power for protection); (b) the absence of any ideological fault-lines

(that might rigidly divide states into opposing camps); and (c) the

absence of an all-out Great Power rivalry (that might force smaller

states to choose sides). Hedging behaviour is possible only when

all three conditions are fulfilled.

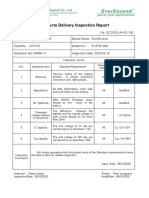

Deconstructing Hedging: Southeast Asian Responses towards a

Rising China

Based on the above defining parameters, hedging is conceived as a

multiple-component strategy between the two ends of the balancing-

bandwagoning spectrum (see Table I).15 This spectrum is measured

by the degrees of rejection and acceptance on the part of smaller

states towards a Great Power, with pure-balancing representing

the highest degree of power rejection, and pure-bandwagoning the

extreme form of power acceptance.

In the context of Southeast Asia-China relations, hedging consists

of five constituent components, as follows:

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

166 Kuik Cheng-Chwee

Ç -N Л)

If! I

ill I :

о

0)

S "1 Ш

i

2?

V

(S

03

-3

гн 2 со о: и з ^^^^^^^В а.

Q3 (А

Г' (Л

PCÖ fi

H О

i

Ì

I

W

ел

•s S> e ■£• Ж € _

С л 3 g С СО _ Я

а 2^| л g) = t

'S53 vS = ¿ 'S

5 СО

p.

JS S) ^ о ^Ш

G f-i 4J >*^^H -

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Th e Essen ce of Hedging 167

Economic-Pragmatism

This refers to a policy wherein a s

gains from its direct trade and inve

regardless of any political problems

It signifies a neutrality point on t

profit-maximizing itself does not carr

or rejection. Economic-pragmatism

equally emphasized by all original

longest held, dating back to the Co

were still politically at odds with

(PRC).16 In fact, all ASEAN states e

well before they proceeded to estab

ship with Beijing. In the 1960s Sing

state to forge direct commercial an

was followed by Malaysia in 1971,

in 1974 and Indonesia in July 1985. 18 In all cases, economic-

pragmatism had the effects of developing socio-economic linkages

while necessitating a certain level of bureaucratic coordination,

thus establishing the foundations for normalization when political

conditions were ripe.

Bin ding-Engagem en t

Engagement refers to a policy wherein a state seeks to establish and

maintain contacts with a Great Power, for the purposes of creating

channels of communication, increasing "voice opportunities" and

influencing the power's policy choices.19 Binding, on the other

hand, refers to an act in which a state seeks to institutionalize its

relations with a power by enmeshing it in regularized diplomatic

activities. When binding and engagement are combined, they serve

to socialize and integrate a Great Power into the established order,

for the goal of neutralizing the revisionist tendency of the power's

behaviour.20

Malaysia's engagement policy can be traced back to the Cold War

period, when it became the first ASEAN state to establish diplomatic

ties with Beijing in May 1974. In the case of Singapore, although it

did not establish formal relations with the PRC until after Indonesia

had done so in 1990, the city state had long maintained close

"unofficial" contacts with China, as is illustrated by the exchanges

of visits between their leaders since 1975. Throughout this period,

however, the states' engagement posture did not entail any "binding"

element, simply because there was no regularized diplomatic

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

168 Kuik Cheng-Chwee

platform between them. It

was implemented hand-in

creations of various institu

China and the ASEAN sta

China established a mechanism for consultations between the two

foreign ministries in 1991. Singapore followed suit in 1995. At th

multilateral level, the smaller states have also been actively engagin

and binding China in various ASEAN-driven institutions, such a

the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and the ASEAN-China dialogu

process. Among the regional states, Singapore and Malaysia (along

with Thailand) are the most enthusiastic advocates and practitioner

of binding-engagement.

This observation, however, is not to say that the ASEAN states

are taking a united stand vis-à-vis China in these institutions. I

fact, while the smaller states have all attempted to make use of th

institutions as an indispensable platform to deal with the PRC, th

states' actions are, ultimately, aimed at serving their own interests

When their interests converge, the individual states would make

collective move (e.g. their efforts to enmesh China in the ASEAN

led institutions in the early 1990s). However, when their interest

diverge, the states would go their own separate ways (e.g. during

the negotiations over the code of conduct in South China Sea).

Occasional collective efforts, hence, should not be mistaken as a

unified stance.

Limited-Ban d wagoning

Bandwagoning refers to a policy wherein a state, driven by a desire

to win present or future rewards, chooses to align with a Great Power

which displays a prospect for reaching pre-eminence.21 It may exist

in two forms: "pure bandwagoning" (PB) and "limited bandwagoning"

(LB). They are differentiated in at least three ways. First, PB often

takes the form of political and military alignment,22 whereas LB

involves only political partnership that is manifested in: (a) policy

coordination on selective issues; and (b) voluntary deference giving

to the larger partner. Second, PB signifies a zero-sum scenario for

Great Powers, that is, when a state bandwagons with one power,

it simultaneously distances itself from another power. LB, on the

other hand, does not necessarily denote a zero-sum situation. A

state may opt for LB with a rising power while still maintaining

its relations with the existing hegemon. Finally, PB implies an

acceptance of superior-subordinate relations between a patron and

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Essence of Hedging 169

a smaller actor, whereas in LB, t

losing its autonomy or becoming

acceptance whereas LB is hierarch

As is demonstrated below, a de

that China's influence is likely

inducements identified by Rand

bandwagoning - have motivated

these factors, however, have enc

same direction.

On a comparative basis (see Table 1), it can be observed that

Thailand shares Malaysia's position in embracing LB, whereas

Indonesia concurs with Singapore in rejecting LB as an option (albeit

for different reasons). Malaysia's LB behaviour is reflected in its

elites' willingness to accord deference to Beijing over the latter's

core interests (e.g. "One China" Policy), as well as their inclination to

see Beijing as a partner in pushing for certain common foreign policy

goals. In this regard, Thailand has similarly worked together with

Beijing to push for various Thai-initiated programmes, such as the

Asian Cooperation Dialogue (ACD). Besides, perhaps as a reflection of

Thai diplomatic culture of bending- with-the- wind, Bangkok has shown

an even greater readiness to display allegiance to China over Taiwan,

Tibet and the Falun Gong.23 Indonesia's policy, by contrast, does not

exhibit clear elements of LB. First, except in the economic domain,

Indonesia does not forge major policy coordination with China in the

same way that Thailand and Malaysia have collaborated with China

over ACD and East Asian cooperation respectively. Second, Jakarta

does not - and probably would not - demonstrate a readiness to

give deference to Beijing in the same way that Bangkok and Kuala

Lumpur have occasionally chosen to do so. Indonesia's position thus

comes closer to that of Singapore. However, unlike Jakarta which

rejects LB primarily because of its elites' perception of Beijing as a

"natural geopolitical rival",24 Singapore's no-bandwagoning stance is

chiefly due to its leaders' acute sensitivity over autonomy, as well

as their wariness about the long-term ramifications of a powerful

China, as will be discussed.

While the above policy thrusts connote more persuasive and

profit-maximizing elements, this is not the case for the remaining two.

Dominance-Denial

This policy is aimed at preventing and denying the emergence

a predominant power that may exert undue interference on sma

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

170 Kuik Cheng-Chwee

states.25 Its modus operandi is

actors, either individually or

(a) involving other powers

their own resilience and str

clout. It is different from

is about balance-of-political

military-power.26 Second, p

country (or bloc) in mind,

targeting at a particular pow

Dominance-denial is adopt

as evidenced by their comm

not necessarily equal - relat

policy has been in practice

after the reduced Western commitments in the late 1960s.

Dominance-denial and binding-engagement can be seen as

two different sides of the same coin. They are related because

both are aimed at influencing a Great Power by binding it in an

institutional web that involves other major actors. However, they

are two distinctive approaches because unlike binding-engagement

that seeks to change the Great Power's action by a persuasive point

("let's preserve the status quo together, because you too have a stake

in it"), dominance-denial seeks to do the same with an implicitly

more confrontational message ("don't dictate us in a hegemonic way,

or we will have no choice but to move closer to other powers").

Given that ASEAN states' own capabilities will never be adequate

to guarantee an effective binding-engagement policy, other powers'

presence is essential to induce China to stay on the engagement

course and to behave in a restrained way. ASEAN states' effort to

ensure other Great Powers involvement in the ARF and the East

Asia Summit is a case in point.

Indirect-Balancing

This is a policy wherein a state makes military efforts to cope w

diffuse uncertainties (as opposed to a specific threat in the case

pure-balancing) by forging defence cooperation and by upgradi

its own military. It is different from "soft-balancing", which ref

to the act of maintaining informal military alignment for balanc

purposes.27 There are reasons why the present study uses "indire

rather than "soft" to describe ASEAN states' balancing acts. To be

with, the issue of informal vs. formal military cooperation betw

ASEAN states and Western powers is largely attributable to facto

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Essence of Hedging 171

other than the rise of China, and

the states' China policies. By con

direct balancing may usefully ref

Beijing. That is, if and as soon a

threat, the state is expected to ma

targeted at China. If this happens

to direct balancing. Presently, how

ASEAN states are seeing China as

are developing defence capabilit

military modernization. Hence, it

states' postures still remains on

* * *

These components indicate that hedging, in essence, is a

two-pronged approach. It is two-pronged because it operates by

simultaneously pursuing two sets of mutually counteracting policies,

which can be labelled as "return-maximizing" and "risk-contingency"

options. The first set - consisting of economic-pragmatism, binding-

engagement and limited-bandwagoning - allows the hedger to reap

as much economic, diplomatic and foreign policy profits as possible

from the Great Power when all is well. It is counteracted by the

risk-contingency set, which, through dominance-denial and indirect-

balancing, aims at reducing the hedger's loss if things go awry. Hedging,

thus, is a strategy that works for the best and prepares for the worst.

A policy that focuses on merely return-maximizing without preparing

for risk contingency - and vice versa - is not a hedging strategy.

By concurrently adopting these options, smaller states such as

Singapore and Malaysia aim to offset possible risks that may arise from

the uncertain regional order. Regardless of how the power structure will

evolve - whether the US commitment will remain strong; whether

Beijing will turn revisionist; whether China will become weak and will

no longer be seen as an alternative power centre; whether China will

grow stronger; or whether China will co-exist peacefully with Japan and

India - the states hope that their act of counteracting one transaction

against another will serve to insure their long term interests.

The assertion here that the original ASEAN members have all

adopted a hedging position does not imply that they are pursuing

a common strategy vis-à-vis Beijing. Far from it, as is reflected in

the earlier discussion on limited-bandwagoning, there are in fact

subtle differences across the states' responses. This will be further

elaborated in the following pages.

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

172 Kuik Cheng-Chwee

Operationalizing Hedging

This section compares Ma

operationalizing the consti

earlier.

Malaysia's China Policy

The evolution of Malaysia's

hostile and mutually suspi

into a cordial partnership

1980s, Malaysia still percei

largely due not only to Ch

Communist Party of Mal

Chinese policy and the Spr

Since the end of the Cold

much more sanguine out

to three factors: (a) the dissolution of the CPM in 1989, which

removed a long-standing political barrier; (b) the growing salience

of economic performance as a source of legitimacy for the ruling

Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition; and (c) Prime Minister Mahathir

Mohamad's foreign policy aspirations. These factors have led to a

shift in Malaysian elite perceptions of China, from a major threat

to a key economic and foreign policy partner.30 Accordingly, in

addition to deepening its long-held economic-pragmatism, Malaysia

has slowly pursued policies that can be seen as binding-engagement

and limited-bandwagoning.

Malaysia's economic-pragmatism is best illustrated by its leaders'

high-level visits to China, which have always been accompanied by

large business delegations and resulted in many joint-venture projects.

Mahathir made seven such visits during his tenure, while the current

Prime Minister Abdullah Badawi paid a major visit in May 2004.

Since 2001, China has been Malaysia's fourth largest trading partner.

Bilateral trade has increased by more than eight-fold over the past

decade, from US$2.4 billion in 1995 to US$19.3 billion in 2004.31

Presently, Malaysia's trade with China is growing at a faster rate than

that with the United States or Japan, the country's two traditional

major trading partners. If this trend continues, it is likely to help

reduce the risk of export volatility for Malaysia.

Binding-engagement is manifested in Malaysia's various efforts

that are aimed at increasing dialogue opportunities with China. In

April 1991, Malaysia and China established a consultative mechanism

between their foreign ministries.32 Above the bilateral level, Malaysia

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Essence of Hedging 173

has joined hands with its ASE

regional level. China's appeara

Meeting in July 1991 - as a gu

- was Beijing's first multilatera

the foundation for China's subse

multilateral processes in the reg

and agreed to embark on the AS

(SOM) Consultation in 1995. It th

Ministerial Conference as a dial

allowing Malaysia (and other AS

the rising power at a time of stra

have also provided valuable plat

South China Sea dispute.34

Malaysia asserted its claim to

in 1979. The country's defenc

of China's intentions in the area

tion of law on the territorial s

stand-off over Mischief Reef in 1

the Malaysian leadership under

dispute to impede his goal of pr

ties with China. This became a

October 1995, Malaysia and Chi

"any form of outside interferen

May 1999, they signed a Joint

the settlement of disputes thro

and negotiations".36 In July t

Philippines' request to discuss

while Manila protested vehemen

structures on Investigator Sho

was low-key. Considering that

in Beijing just before the constr

conjecture", a well-informed Ma

minister was "actually dispatc

the latest development over Ma

Malaysia's moves, of course, were not so much about

accommodating China's position, but more about cashing in on its

like-minded views with the power for promoting its own interests

on the Spratlys, namely defending its territorial claims with a

view to exploiting maritime resources. According to Joseph Liow,

given that Malaysia's claimed territory in the South China Sea

lies furthest from China, this has kept both countries "from actual

conflict over their respective claims and in turn has facilitated

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

174 Kuik Cheng-Chwee

easier bilateral cooperation

the two countries have sim

quo" in the dispute.38

Malaysia's limited-bandw

East Asian cooperation. Pa

partly due to Beijing's int

valuable partner in pushing

among the East Asian eco

Mahathir's East Asia Econ

which he advocated a gro

collective interests in the

the West. The proposal wa

and received only a lukew

and other ASEAN members, even after it was renamed the East Asia

Economic Caucus (EAEC). Tokyo's response came as a disappointment

to Malaysia, which originally hoped that Japan would play a leading

role in the group. In due course, China stood out as the only

major power which lent explicit support to EAEC. In 1997, China,

along with Japan and South Korea, accepted ASEAN's invitation

to attend an informal summit, which evolved as the ASEAN Plus

Three (APT) process. In 2002, Kuala Lumpur's attempt to set up an

APT Secretariat was opposed by some ASEAN members, but was

supported by Beijing. In 2004, when Malaysia proposed to convene

the inaugural East Asia Summit (EAS), the proposal was backed by

China. During the run-up to the Summit in the following year, both

Malaysia and China favoured limiting EAS membership to the APT

countries. Later, when it became clear that India, Australia and New

Zealand would be included in the new forum, the two countries,

along with others, then advocated making the APT as the "main

vehicle" for East Asia community building, and the EAS "a forum

for dialogue" among the regional countries.

The growing bilateral and multilateral interactions since the

early 1990s have also offered opportunities for Malaysia and China

to discover that they share important commonalities over many

international issues. These range from human rights, the cause of

the developing world, opposition to the US-dominated international

order, and so on. The congruence of interests in these areas has

led them to support each other's position at various international

forums.39

The convergence of foreign policy interests, combined with the

tangible economic benefits, have lead Malaysian elites to downplay, if

not overcome, their earlier apprehensions about the potential security

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Th e Essen ce of Hedging 175

ramifications of a powerful neighbour

Abdullah in 2004: "Malaysia's Chin

good diplomacy and good sense. ..

for others to follow. Our China po

beyond your fears and inadequaci

principled positions, rewards will f

Driven chiefly by this belief, bot

efforts to reiterate and internalize

on various occasions, often referri

Zheng He's peaceful voyages to Mala

case to highlight the benevolent na

the leaders' open rhetoric has largel

Notwithstanding the lingering conc

forces about China's long-term intent

Malaysia is pursuing pure-balancing

defence modernization does not ref

targeted at China.41

To be sure, Malaysia has long been a

Defence Arrangements (FPDA), an

ties with the US. In May 2005, M

Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Ag

in 1994. These arrangements, howev

of "indirect" rather than direct-ba

appear to have more to do with the

than to target a specific threat. As

Zakaria Haji Ahmad, the view in

that "China will not enact policie

it will be benign." He adds that i

future, "there is no notion of the

'balance', counter or neutralize Ch

actions, should Beijing choose to ac

To Malaysian leaders, the notion

more than a self-fulfilling prophe

telling illustration: "Why should

a country as your future enemy, i

- because then they will identify y

be tension."43 In this regard, the b

signed in September 2005 is signific

that Malaysia is now more willing t

than a security threat.

That limited-bandwagoning has be

does not imply that Malaysia favou

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

176 Kuik Cheng-Chwee

order. In fact, dominance-

for Malaysia, as indicated b

all major powers. As emph

Razak, the decision to acce

means a reflection of our f

towards China".44 Given Mal

with the complex relations

the minority Chinese, Mala

to remain limited in the near future.

Singapore's China Policy

The peculiarity of Singapore's China policy is that it is by design

an ambivalent one: warm in economic and diplomatic ties but

distanced in political and strategic spheres.

Under the People's Action Party (PAP)'s rule, economic impera-

tives have always been a key driving force behind Singapore's

China policy. As far back as the 1960s and throughout the 1980s,

in the absence of diplomatic relations, Singapore already actively

promoted bilateral economic ties. The launch of China's open-door

policy in 1978, coupled with Singapore's economic recession in the

mid-1980s and the government's plan to develop a "second wing"

of the Singaporean economy, all provided additional incentives for

Singapore to exploit growing economic opportunities in China. Largely

because of the complementary nature of the two economies, Singapore

has long been China's largest trading partner in ASEAN, except in

2002 and 2003. Beyond trade, bilateral economic cooperation has

taken the forms of investment and management skills transfer, as

illustrated by the flagship Suzhou Industrial Park project.

On the diplomatic front, Singapore has been one of the key

advocates of binding-engagement policy since the early 1990s.

Together with other ASEAN states, it has implemented the policy

both through economic incentives and regional institutions, such as

the ARE45 By binding Beijing to a web of institutions, Singapore

hopes to give China a stake in regional peace and stability.46 To quote

a Singaporean scholar: "Singapore wants to see China enmeshed

in regional norms, acting responsibly and upholding the regional

status quo."47

One might wonder: why does Singapore care so much about

"regional status quo" and how is China factored in? To begin with,

Singapore is a tiny state with innate vulnerability. This vulnerability is

rooted in its minuscule size, its limited resources and its geopolitical

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Essence of Hedging 177

setting. To cope with the vuln

resorted to a three-fold appr

interdependence, pursuing arm

regional balance of power.48 Th

to the maintenance of regional-st

at sea; (b) a cohesive ASEAN; and

there is no safe and free navigat

economic viability will be sever

divided, Singapore will not be a

in shaping external affairs; and

capabilities among the Great Po

compromised by the emergence

of these possibilities may weak

to ensure sustainable prosperity

potential risks to their very leg

It is in this light that Singa

and the Spratlys. Given Singapo

trade, its leaders have been nerv

in the Taiwan Straits. During t

feared that any armed conflict

foreign trade and investment".4

a claimant to the Spratlys, it is

a bearing on the safety of navi

In addition, Singaporean lead

a strong China will exercise i

uncertainties over Beijing's future

taken "a fall-back position" for

very much a reflection of a "

by Yuen-Foong Khong. In his

"think in terms of possible sce

might affect Singapore".52 Giv

absence of territorial disputes, C

Singapore. The city state's thou

the mid- to long-term, i.e., whe

regional stability and prosper

choices; and (c) drive a wedge b

would undermine ASEAN cohesion.53

Singapore's quintessence as an anticipatory state is well illustrate

by a decision it made at the end of the Cold War. In 1989, w

it appeared that the US might have to close its military bas

in the Philippines, Singapore announced that it would grant

Americans access to its facilities. Singapore's move was driven b

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

178 Kuik Cheng-Chwee

its fear that the US with

Asia Pacific, which would

regional powers. If that ha

in turn, would threaten Si

Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew decided to "stick with what has

worked so far", i.e., the American military presence that he s

as the key to order and stability in East Asia.54 Lee's decision

aimed at coping with strategic uncertainty in the post-Cold W

environment; China's actions over Mischief Reef in 1995 validated

his concerns. In 1998, Singapore further strengthened its security

ties with America by constructing a new pier at its Changi Naval

Base, designed specifically to accommodate US aircraft carriers.

While Singapore's indirect-balancing has relied primarily on its

military cooperation with the US, it would be wrong to attribute

Singapore-US ties entirely to the China factor. In fact, Singapore's

recent move to strengthen its security relations with Washington

have less to do with China than its concerns over terrorism, following

the 11 September 2001 attacks in the US as well as the arrest of

the Al Qaeda-linked Jemaah Islamiyah members in Singapore in

December 2001. According to Evelyn Goh, the new counter-terrorism

agenda now acts "as stronger glue for the Singapore-US strategic

partnership than the China challenge".55

This development, however, does not mean that China has been

dropped from Singapore's list of strategic concerns. In fact, despite

Beijing's so-called "charm offensive" in recent years, Singapore still

cautiously guards against any potential risks of a powerful China.

As remarked by Goh Chok Tong in 2003:

China is conscious that it needs to be seen as a responsible power

and has taken pains to cultivate this image. This is comforting to

regional countries. Nevertheless, many in the region would feel

more assured if East Asia remains in balance as China grows. In

fact, maintaining balance is the over-arching strategic objective in

East Asia currently, and only with the help of the US can East

Asia achieve this.56

In this context, the bilateral diplomatic feud that sparked right after

Prime Minister-designate Lee Hsien Loong's visit to Taipei in 2004 may

have deepened Singapore's trepidation over a too powerful China.

Finally, Singapore's policy is also marked by its rejection of

limited-bandwagoning due to its demographic profile and geopolitical

complexity. Ever since Singapore became independent in 1965, the

island, where ethnic Chinese make up 76 per cent of the population,

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Essence of Hedging 1 79

has been uneasy about being seen a

its larger and Muslim-majority ne

During the Cold War, chiefly out

that it would be the "front post of

it would be the last ASEAN state t

Beijing. During the post-Cold W

attempts to downplay ethnic affinity

to avoid leaving any impression tha

in the region.58 For this reason, t

the part of Singapore as to the ext

ties with Beijing.59 Hence, bandwa

form, does not appear to be a like

Conclusion

The preceding analysis has reflected that Malaysia and Singapore's

response to a rising China cannot be adequately explained by neo-

realism. In the first place, neo-realism does not sufficiently captur

the range of state options and functions in the face of power

asymmetries. Neo-realists maintain that when faced with a rising

power, states are likely to opt for internal and external balancing

acts, for the function of threat-reduction. Our discussion, however,

suggests that state options are not confined to balancing (and

its anti-thesis, bandwagoning), but may include mixed strategie

such as hedging, which involves a combination of both military

and non-military options, with particular reliance on multilateral

institutions. Our discussion also reveals that state functions are not

limited to threat-reduction, but may involve the concurrent goals

of risk-contingency and return-maximizing. This is not to say that

neo-realism is irrelevant in explaining small-state responses to a

rising power. It merely suggests that the paradigm is more useful

in accounting for a situation where states are confronted by an

immediate security threat. In circumstances where states' security

is not directly at stake - as with the two cases under examination

- neo-realism has lost much of its explanatory strength.

Moreover, the limitations of neo-realism also lie with its

inadequacy to explain the variation in state responses. As discussed,

the growth of China's relative power since the 1990s has induced

Malaysia (and Thailand) to move closer to Beijing by embracing

limited-bandwagoning, but the very same structural force clearly did

not cause the same effect in the case of Singapore (and Indonesia).

It thus follows that structural factors per se have no inherent

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

180 Kuik Cheng-Chwee

consequence on state behav

that may have affected th

domestic factors is further

is Malaysia and not Singapo

China. Considering Malaysi

dispute, one would expec

than Singapore, which do

claims with Beijing and is g

record as discussed, howev

This is where the Regime

a nutshell, it argues that it

that explain the variation

In the case of Malaysia

mirrors the sources of th

inter alia, the elite's capacity to promote Malay dominance,

economic growth, electoral performance, national sovereignty and

international standing. Pure-bandwagoning (an across-the-board

alignment and an acceptance of hierarchical relations) is a non-

starter for the Malay-dominated regime, as the option is likely to

result in an imbalance in domestic political configuration and an

erosion of external sovereignty. The limited form of bandwagoning,

however, is desirable and in fact vital for the BN government. Given

Malaysia's multi-racial structure, a politically significant economic

growth requires the elite to concurrently attain the improvement of

the Malays' economic welfare and the enlargement of the overall

economic pie for the non-Malay groups.60 For the ruling elite, this is

indeed a key to consolidating their electoral base. In this respect, a

closer relationship with Beijing is crucial for the BN elite not only

because it boosts bilateral economic ties, but also because China's

support will strengthen Malaysia's ability to promote a new economic

order for East Asia. This ambition, if materialized, is expected to

elevate Malaysia's regional and international standing - itself an

important source of authority for BN. Hence, pure-balancing against

Beijing is not only unjustifiable, but it will also be harmful to BN

regime interests. This is because such an option would call for a

full-fledged alliance with the US, which is likely to reduce the

credibility of the BN's claim of pursuing an "independent" external

policy for Malaysia.

In Singapore's case its ambivalent policy towards China is best

explained by the foundation of PAP's domestic legitimacy, i.e.,

an ability to cope with the city state's inherited vulnerability. An

economically close and diplomatically cordial relationship with

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Th e Essen ce of Hedging 181

China serves to attain this goal

and regional stability), but a str

would not. Rather, any bandwag

only increase Singapore's vulnera

its two larger neighbours. For a "l

as a Chinese island in a Malay se

destabilize Singapore's immediate

the PAP elites' attention from the otherwise more crucial domestic

economic functions.

To conclude, the substance of the states' reactions to a rising

power is not so much determined by the growth of the power's

relative capabilities per se; rather, it is a function of regime

legitimation through which the respective elites seek to capitalize

on the dynamics of the rising power for the goal of justifying and

enhancing their own authority at home. This study is of significance

for policy analysis. Given that very few states are adopting pure

forms of balancing or bandwagoning vis-à-vis China, conceptualizing

hedging as a spectrum of policy options is a more realistic way

to observe the change and continuity in state strategies over time.

Specifically, it allows policy analysts to ponder the possibility,

direction and conditions of a horizontal shift along the spectrum,

thereby providing useful pointers for systematically studying the

patterns of states' strategic choices amid the evolving power structure

in the twenty-first century.

NOTES

1 A shorter version of this essay originally appeared in BiblioAsia 3, no. 4

(January 2008), pp. 4-13. The author gratefully acknowledges the financial

support of the Fulbright Program, the UKM Study Leave Scheme, the SAIS

Doctoral Fellowship, the Lee Kong Chian Research Fellowship (National Library

Board, Singapore), and the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation. He would also like

to express his appreciation to Karl Jackson, David Lampton, Francis Fukuyama,

Bridget Welsh, Wang Gungwu, Zakaria Haji Ahmad, Hari Singh, Ian Storey,

Kong Bo, Goh Muipong, Jessica Gonzalez, Jim and Joanie Allison, Laura Deitz,

John Copper, Yong Pow Ang and the journal's anonymous reviewers for their

helpful comments on the earlier drafts of the paper.

2 Kenneth Waltz, Theory of International Politics (Reading, Mass: Addison- Wesley,

1979).

3 Stephen Walt, "Alliance Formation and the Balance of World Power", International

Security 9, no. 4 (Spring 1985): 3-43.

4 Randall Schweller, "Bandwagoning for Profit: Bringing the Revisionist State

Back In", International Security 19, no. 1 (Summer 1994): 72-107.

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

182 Kuik Cheng-Chwee

5 Alastair Iain Johnston and Ro

of an Emerging Power (New Yo

Wrong: The Need for New Ana

no. 4 (Spring 2003): 57-85; Am

International Security 28, no.

6 Amitav Acharya, "Containmen

Response to the Rise of China",

p. 140.

7 Herbert Yee and Ian Storey, e

Reality (London: RoutledgeCurzo

Asia: Asymmetry, Leadership an

2003-04): 529-48.

8 Amitav Acharya has rightly cautioned that engagement cannot be viewed as

bandwagoning "because it does not involve abandoning the military option

vis-à-vis China". He also stresses that economic self-interest should not be confused

with bandwagoning because economic ties "do not amount to deference". See

Acharya, "Will Asia's Past Be Its Future?", op. cit., 151-52.

9 Johnston and Ross, Engaging China, op. cit., p. 288; Chien-Peng Chung, "Southeast

Asia-China Relations: Dialectics of 'Hedging' and 'Counter-Hedging'", Daljit

Singh and Chin Kin Wah, eds., Southeast Asian Affairs 2004 (Singapore: ISEAS,

2004), pp. 35-53; Evelyn Goh, Meeting the China Challenge, Policy Studies 16

(Washington, D.C.: East West Center Washington, 2005); Francis Fukuyama and

John Ikenberry, Report of the Working Group on Grand Strategic Choices, The

Princeton Project on National Security (September 2005), pp. 14-25; Bronson

Percival, The Dragon Looks South (Westport, CT & London: Praeger Security

International, 2007).

10 On inner justification of the "right to govern", see Max Weber, "Legitimacy,

Politics, and the State", in William Connolly, ed., Legitimacy and the State

(New York: New York University Press, 1984), pp. 32-62; David Beetham,

The Legitimation of Power (London: MacMillan, 1991); Muthiah Alagappa, ed.,

Political Legitimacy in Southeast Asia (Stanford: Stanford University Press,

1995).

11 On neo-realism, see Waltz, Theory of International Politics, op. cit.; Robert Keohane,

ed., Neorealism and Its Critics (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986).

12 This definition is adapted from Glenn Munn et al., Encyclopedia of Ranking and

Finance, 9th edition (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1991), p. 485; Jonathan Pollack,

"Designing a New American Security Strategy for Asia", in James Shinn, ed.,

Weaving the Net: Conditional Engagement with China (New York: Council on

Foreign Relations, 1996), pp. 99-132; Goh, Meeting the China Challenge, op.

cit., pp. 2-4.

13 On ASEAN's discourse of "uncertainty", see Yuen Foong Khong, "Coping with

Strategic Uncertainty: The Role of Institutions and Soft Balancing in Southeast

Asia's Post-Cold War Strategy", in J.J. Suh, Peter Katzenstein, and Allen Carlson,

eds., Rethinking Security in East Asia (Stanford: Stanford University, 2004).

14 Michael Leifer, The ASEAN Regional Forum: Extending ASEAN's Model of

Regional Security, Adelphi Paper no. 302 (London: Oxford University Press for

IISS, 1996); Khong, "Coping with Strategic Uncertainties", op. cit.

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Essence of Hedging 183

15 The need to go beyond the dichotomou

Acharya and Ja Ian Chong. See Acharya,

Dominance?", op. cit.; Chong, Revisitin

Working Paper no. 54 (Singapore: Insti

2003).

16 Stephen Leong, "Malaysia and the Pe

Political Vigilance and Economic Pragma

1987): 1109-26.

17 Chia Siow-Yue, "China's Economic Relations with ASEAN Countries", and Chin

Kin Wah, "A New Phase in Singapore's Relations with China", both in Joyce

Kallgren et al. eds., ASEAN and China: An Evolving Relationship (Berkeley:

University of California, 1988), pp. 189-214 and pp. 274-91 respectively.

18 Ibid; John Wong, The Political Economy of China's Changing Relations with

Southeast Asia (London: Macmillan, 1984).

19 Adapted from Schweller, "Managing the Rise of Great Powers"; Yuen Foong

Khong, "Singapore: A Time for Economic and Political Engagement", both

in Johnston and Ross, Engaging China, op. cit., pp. 13-15 and pp. 110-13,

respectively.

20 Ibid.

21 Schweller, "Bandwagoning for Profit", op. cit.

22 Ibid; Acharya, "Will Asia's Past Be Its Future?", op. cit., p. 151

23 Anthony Smith, "Thailand's Security and the Sino-Thai Relat

Rrief 5, Issue 3 (2005), p. 3.

24 Michael Leifer, "Indonesia's Encounters with China and the Dilemmas of

Engagement", in Johnston and Ross, Engaging China, op. cit., p. 99.

25 This term is adapted from "counter-dominance", as coined by Amitav Acharya,

"Containment, Engagement, or Counter-Dominance?", op. cit., pp. 129-51.

26 Ralf Emmers, Cooperative Security and the Ralance of Power in ASEAN and

the ARF (London & New York: Routledge, 2003).

27 "Soft balancing" is used as a contrast to "hard balancing", which refers to

formal and strict sense of military alliance. See Khong, "Coping with Strategic

Uncertainties", op. cit.

28 Abdul Razak Baginda, "Malaysian Perceptions of China: From Hostility to

Cordiality", in Yee and Storey, The China Threat, op. cit., pp. 227-47.

29 Wang Gungwu, "China and the Region in Relation to Chinese Minorities",

Contemporary Southeast Asia 1, no. 1 (May 1979): 36-50; Leong, "Malaysia

and the People's Republic", op. cit., pp. 1109-26; and J.N. Mak, "The Chinese

Navy and the South China Sea: A Malaysian Assessment", Pacific Review 4,

no. 2 (1991): 150-61.

30 Joseph Liow Chinyong, "Malaysia-China Relations in the 1990s: The Maturing

of a Partnership", Asian Survey 40, no. 4 (July /August 2000): 672-91.

31 Malaysia Trade and Industry Portal, Trade and Investments Statistics, available

at <http://www.miti.gov.my>.

32 Mohamad Sadik Gany, Malaysia's China Policy, M.A. unpublished paper (Bangi

& Kuala Lumpur: UKM-IDFR, 2001).

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

184 Kuik Cheng-Chwee

33 Kuik Cheng-Chwee, "Multilat

Southeast Asia 27, no. 1 (April

in Asia: The Aussenpolitik and I

Francis Fukuyama, eds., East A

University Press, 2008), pp. 10

34 Lee Lai To, China and the So

1999).

35 Liow, "Malaysia-China Relati

36 Joint Statement between the

the People's Republic of China o

31 May 1999.

37 Baginda, "Malaysian Perceptions of China", in Yee and Storey, The China

Threat, op. cit., p. 244.

38 Liow, "Malaysia-China Relations", op. cit., pp. 688-89.

39 Ibid., pp. 679-80.

40 Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, Prime Minister of Malaysia, keynote address to the

China-Malaysia Economic Conference, Sunway, 24 February 2004.

41 Liow, "Malaysia-China Relations", op. cit., pp. 682-83.

42 Zakaria Haji Ahmad, "Malaysia", in Evelyn Goh, ed., Betwixt and Between:

Southeast Asian Strategic Relations with the U.S. and China, IDSS Monograph

no. 7 (Singapore: IDSS, 2005), pp. 58-59.

43 "I Am Still Here: Asiaweek's Complete Interview with Mahathir Mohamad",

Asiaweek, 9 May 1997.

44 Mohd Najib Tun Abd Razak, Deputy Prime Minister of Malaysia, "Strategic

Outlook for East Asia: A Malaysian Perspective", keynote address to the Malaysia

and East Asia International Conference, Kuala Lumpur, 9 March 2006.

45 Khong, "Singapore", op. cit., pp. 109-28.

46 Allen Whiting, "ASEAN Eyes China: The Security Dimension", Asian Survey

37, no. 4 (April 1997).

47 Evelyn Goh, "Singapore's Reaction to a Rising China: Deep Engagement and

Strategic Adjustment", in Ho Khai Leong and Samuel C.Y. Ku, eds., China

and Southeast Asia: Global Changes and Regional Challenges (Singapore and

Kaohsiung: ISEAS and CSEAS, 2005), p. 313.

48 Michael Leifer, Singapore's Foreign Policy: Coping with Vulnerability (New York:

Routledge, 2000).

49 Whiting, "ASEAN Eyes China", op. cit., p. 308.

50 Ian Storey, "Singapore and the Rise of China", in Yee and Storey, The China

Threat, op. cit., p. 213.

51 Khong, "Singapore", op. cit., p. 121.

52 Ibid., p. 113.

53 Goh, Meeting the China Challenge, op. cit., p. 13.

54 Khong, "Coping with Strategic Uncertainties", op. cit., pp. 181-82.

55 Goh, Meeting the China Challenge, op. cit., pp. 13-15.

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Th e Essen ce of Hedging 185

56 Goh Chok Tong, "Challenges for Asia", Speech Delivered at the Research

Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) Special Seminar, Tokyo,

28 March 2003.

57 Leo Suryadinata, China and the ASEAN States: The Ethnic Chinese Dimension

(Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Academic, 1985/2005), p. 81.

58 Khong, "Singapore", op. cit., p. 119; Goh, "Singapore's Reaction to a Rising

China", op. cit., p. 316.

59 Khong, "Singapore", op. cit., p. 119.

60 Liow, "Malaysia-China Relations", op. cit., p. 676.

This content downloaded from

83.40.156.97 on Sun, 31 Mar 2024 11:24:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Global Security Upheaval: Armed Nonstate Groups Usurping State Stability FunctionsFrom EverandGlobal Security Upheaval: Armed Nonstate Groups Usurping State Stability FunctionsNo ratings yet

- Kuik - The Essence of Hedging - Reading NotesDocument12 pagesKuik - The Essence of Hedging - Reading NotesTimothy Brandon TanNo ratings yet

- Hedging in South AsiaDocument30 pagesHedging in South AsiaYuming LiuNo ratings yet

- Contesting Hegemonic Order China in East AsiaDocument32 pagesContesting Hegemonic Order China in East AsiaSOFIA PEDRAZANo ratings yet

- Resistance Dynamics and Social Movement Theory Conditions, Mechanisms, and EffectsDocument21 pagesResistance Dynamics and Social Movement Theory Conditions, Mechanisms, and EffectssergiolefNo ratings yet

- Revisiting Responses to American Power: Going Beyond Balancing and BandwagoningDocument31 pagesRevisiting Responses to American Power: Going Beyond Balancing and BandwagoningAnthony Medina Rivas PlataNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Power in International Relations According to RealismDocument6 pagesThe Concept of Power in International Relations According to RealismMatthew EvanNo ratings yet

- Rasheed ConceptPowerInternational 1995Document6 pagesRasheed ConceptPowerInternational 1995dozhaoNo ratings yet

- ADDING HEDGING TO THE MENUDocument56 pagesADDING HEDGING TO THE MENUchikidunkNo ratings yet

- Who's Chasing Whom? Vietnam-US Relations and Theories of Alignment and AllianceDocument49 pagesWho's Chasing Whom? Vietnam-US Relations and Theories of Alignment and AllianceThanh Dat TranNo ratings yet

- 李舒凡 109253024Document5 pages李舒凡 109253024Виктория ПогребенкоNo ratings yet

- Strategic Hedging and The Future of Asia-Pacific Stability: Evan S. MedeirosDocument24 pagesStrategic Hedging and The Future of Asia-Pacific Stability: Evan S. MedeirosWu GuifengNo ratings yet

- Kuik WhatDoWeakerStatesHedgeAgainstDocument24 pagesKuik WhatDoWeakerStatesHedgeAgainstMinh Giang Hoang NguyenNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 106.78.46.44 On Tue, 18 Aug 2020 17:43:51 UTCDocument16 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 106.78.46.44 On Tue, 18 Aug 2020 17:43:51 UTCabhijeet nafriNo ratings yet

- US China Strategic Competition and ConveDocument18 pagesUS China Strategic Competition and ConveWorkaholic.No ratings yet

- Alliance Theory and Alliance Shelter': The Complexities of Small State Alliance BehaviourDocument19 pagesAlliance Theory and Alliance Shelter': The Complexities of Small State Alliance BehaviourLivia StaicuNo ratings yet

- Understanding the South China Sea Dispute Using Analytic EclecticismDocument25 pagesUnderstanding the South China Sea Dispute Using Analytic EclecticismNovella LerianNo ratings yet

- Lake AnarchyHierarchyVariety 1996Document34 pagesLake AnarchyHierarchyVariety 1996leamadschNo ratings yet

- Securitization of US-CHINA Relations: A Catalyst For ConfrontationDocument28 pagesSecuritization of US-CHINA Relations: A Catalyst For ConfrontationGovernance and Society ReviewNo ratings yet

- Nagy - 2020 - Middle Power Alignment in The Indo-PacificDocument14 pagesNagy - 2020 - Middle Power Alignment in The Indo-PacificHuỳnh Tâm SángNo ratings yet

- Pak-US Alliance Curse: Some Hypotheses: September 2020Document16 pagesPak-US Alliance Curse: Some Hypotheses: September 2020Alyan WaheedNo ratings yet

- Waltz 1979, p.123 Waltz 1979, p..124 Waltz 1979, p.125 Waltz 1979, p.125 Waltz 1979, p.127Document5 pagesWaltz 1979, p.123 Waltz 1979, p..124 Waltz 1979, p.125 Waltz 1979, p.125 Waltz 1979, p.127TR KafleNo ratings yet

- RiskDiversificationandUAEForeignPolicy SHERWOOD FNDocument35 pagesRiskDiversificationandUAEForeignPolicy SHERWOOD FNSreejith RamadasanNo ratings yet

- A Critique Paper by Hedrick Alcantara - C-PSCM314Document3 pagesA Critique Paper by Hedrick Alcantara - C-PSCM314Ck AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- How Power Relations Emerge in Competitive Capitalist EconomiesDocument31 pagesHow Power Relations Emerge in Competitive Capitalist Economieslcr89No ratings yet

- Countering The Hegemon: Pakistan's Strategic Response: Dr. Zulfqar KhanDocument30 pagesCountering The Hegemon: Pakistan's Strategic Response: Dr. Zulfqar KhanparasshamsNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 86.30.238.79 On Tue, 28 Sep 2021 19:37:26 UTCDocument13 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 86.30.238.79 On Tue, 28 Sep 2021 19:37:26 UTCNecati EtliogluNo ratings yet

- Interests, Power and China's Difficult Game in The Shanghai Cooperation OrgDocument18 pagesInterests, Power and China's Difficult Game in The Shanghai Cooperation OrgGuadalupeNo ratings yet

- Mitchell-Prins 2004 Rivalry and Diversionary Uses of ForceDocument25 pagesMitchell-Prins 2004 Rivalry and Diversionary Uses of Force廖恒德No ratings yet

- Systematic Vulnerability and The Origins of Developmental States: Northeast and Southeast Asia in Comparative PerspectivesDocument36 pagesSystematic Vulnerability and The Origins of Developmental States: Northeast and Southeast Asia in Comparative PerspectivesGraceNo ratings yet

- Globalization, Power, and Security Author(s) : SEAN KAY Source: Security Dialogue, Vol. 35, No. 1 (MARCH 2004), Pp. 9-25 Published By: Sage Publications, Ltd. Accessed: 17-02-2019 13:15 UTCDocument18 pagesGlobalization, Power, and Security Author(s) : SEAN KAY Source: Security Dialogue, Vol. 35, No. 1 (MARCH 2004), Pp. 9-25 Published By: Sage Publications, Ltd. Accessed: 17-02-2019 13:15 UTCJANICE RHEA P. CABACUNGANNo ratings yet

- U.S. Strategy for Maintaining Stability in AsiaDocument13 pagesU.S. Strategy for Maintaining Stability in AsiaecdysNo ratings yet

- W2:Keohane - The Demand For International Regimes PDFDocument32 pagesW2:Keohane - The Demand For International Regimes PDFSnowyJcNo ratings yet

- The Theory and Reality of Soft PowerDocument22 pagesThe Theory and Reality of Soft PowermimiNo ratings yet

- REALISMDocument9 pagesREALISMha8191898No ratings yet

- Friedberg 2015Document23 pagesFriedberg 2015DiegoNo ratings yet

- Taiwan's Strategic Choices in Rising ChinaDocument22 pagesTaiwan's Strategic Choices in Rising ChinaAnthony Medina Rivas PlataNo ratings yet

- China Offensive RealismDocument31 pagesChina Offensive RealismSofía KFNo ratings yet

- When Do Leaders Free Ride - Business Experience and Contributions To Collective DefenseDocument16 pagesWhen Do Leaders Free Ride - Business Experience and Contributions To Collective DefenseSean RemeikaNo ratings yet

- Alignment Not Alliance The Shifting Paradigm of International Security Cooperation Toward A Conceptual Taxonomy of AlignmentDocument25 pagesAlignment Not Alliance The Shifting Paradigm of International Security Cooperation Toward A Conceptual Taxonomy of AlignmentNguyễn ThảoNo ratings yet

- Study Material National PowerDocument21 pagesStudy Material National PowerHuzaifa AzamNo ratings yet

- Feminist Foreign PolicyDocument21 pagesFeminist Foreign PolicySaiful BaharNo ratings yet

- The Changing Fundamentals of US-China RelationsDocument28 pagesThe Changing Fundamentals of US-China Relationsapplekung2015No ratings yet

- 1-SS Muhammad Faisal No-4 2020Document20 pages1-SS Muhammad Faisal No-4 2020Jaweria AlamNo ratings yet

- Swain China2Document11 pagesSwain China2obamaNo ratings yet

- Denny Roy PDFDocument15 pagesDenny Roy PDFLWNo ratings yet

- 76 - 1 - Epstein - Rose-REGUACION FONDOS SOBERANOSDocument24 pages76 - 1 - Epstein - Rose-REGUACION FONDOS SOBERANOSingeniero.aeronautico6003No ratings yet

- Hatton Pistor Maximizing AutonomyDocument60 pagesHatton Pistor Maximizing Autonomytomili85No ratings yet

- Jervis - Cooperation Under Sec DilemmaDocument49 pagesJervis - Cooperation Under Sec DilemmaVictoria Den HaringNo ratings yet

- Who Wants To Be A Great Power?: by Lawrence FreedmanDocument12 pagesWho Wants To Be A Great Power?: by Lawrence FreedmansdfghNo ratings yet

- What Are The Critical Issues That Dominate Nigerian Fiscal RelationsDocument9 pagesWhat Are The Critical Issues That Dominate Nigerian Fiscal Relationsqueeniteadeyemi11No ratings yet

- Hard Power, Soft Power and Smart PowerDocument16 pagesHard Power, Soft Power and Smart PowerJerenluis GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Patrick C. Coaty - Small State Behavior in Strategic and Intelligence Studies-Springer International Publishing - Palgrave Macmillan (2019)Document177 pagesPatrick C. Coaty - Small State Behavior in Strategic and Intelligence Studies-Springer International Publishing - Palgrave Macmillan (2019)Yaeru EuphemiaNo ratings yet

- Countering China's Grayzone Strategy in The East and South China SeasDocument111 pagesCountering China's Grayzone Strategy in The East and South China Seasidseintegrationbr.oimaNo ratings yet

- Resistance Dynamics and Social Movement Theory Conditions, Mechanisms, and EffectsDocument24 pagesResistance Dynamics and Social Movement Theory Conditions, Mechanisms, and EffectssergiolefNo ratings yet

- Wiley The International Studies AssociationDocument29 pagesWiley The International Studies AssociationCrystal LegionairesNo ratings yet

- Of Mechanisms and Myths: Conceptualising States' Soft Power Strategies Through Sports Mega-EventsDocument36 pagesOf Mechanisms and Myths: Conceptualising States' Soft Power Strategies Through Sports Mega-Eventsrobi_samNo ratings yet

- International Relations Theories ExplainedDocument7 pagesInternational Relations Theories ExplainedMuhammadIqbalNo ratings yet

- The Rise of China, Balance of Power Theory and US National Security Reasons For OptimismDocument43 pagesThe Rise of China, Balance of Power Theory and US National Security Reasons For Optimismdwimuchtar 13100% (2)

- Foreign Affairs, March/April 2011: Charles Glaser Will China's Rise Lead To War?Document11 pagesForeign Affairs, March/April 2011: Charles Glaser Will China's Rise Lead To War?Sidharth RajagopalanNo ratings yet

- Pick Pack Ship Public APIDocument19 pagesPick Pack Ship Public APIgauravpuri198050% (2)

- 2 Both Texts, and Then Answer Question 1 On The Question Paper. Text A: Esports in The Olympic Games?Document2 pages2 Both Texts, and Then Answer Question 1 On The Question Paper. Text A: Esports in The Olympic Games?...No ratings yet

- IBM TS2900 Tape Autoloader RBDocument11 pagesIBM TS2900 Tape Autoloader RBLeonNo ratings yet

- Design and Analysis of Buck ConverterDocument18 pagesDesign and Analysis of Buck Converterk rajendraNo ratings yet

- LINDA ALOYSIUS Unit 6 Seminar Information 2015-16 - Seminar 4 Readings PDFDocument2 pagesLINDA ALOYSIUS Unit 6 Seminar Information 2015-16 - Seminar 4 Readings PDFBence MagyarlakiNo ratings yet

- HonorDishonorProcess - Victoria Joy-1 PDFDocument126 pagesHonorDishonorProcess - Victoria Joy-1 PDFarjay1266100% (3)

- MCQs on PharmacologyDocument101 pagesMCQs on PharmacologyMohammad Rashid88% (8)

- Computer ViruesDocument19 pagesComputer ViruesMuhammad Adeel AnsariNo ratings yet

- FSRE SS AppendixGlossariesDocument27 pagesFSRE SS AppendixGlossariessachinchem020No ratings yet

- Qcs 2010 Section 13 Part 3 Accessories PDFDocument3 pagesQcs 2010 Section 13 Part 3 Accessories PDFbryanpastor106No ratings yet

- Fujitsu Lifebook p1120 ManualDocument91 pagesFujitsu Lifebook p1120 Manualمحمد يحىNo ratings yet

- CD 1 - Screening & DiagnosisDocument27 pagesCD 1 - Screening & DiagnosiskhairulfatinNo ratings yet

- Joe Ann MarcellanaDocument17 pagesJoe Ann MarcellanarudyNo ratings yet

- Setup LogDocument77 pagesSetup Loganon-261766No ratings yet

- cmc2 OiDocument147 pagescmc2 OiJesus Mack GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Gfk-1383a 05012Document108 pagesGfk-1383a 05012occhityaNo ratings yet

- Red Lion Edict-97 - Manual PDFDocument282 pagesRed Lion Edict-97 - Manual PDFnaminalatrukNo ratings yet

- Fisher - Techincal Monograph 42 - Understanding DecibelsDocument8 pagesFisher - Techincal Monograph 42 - Understanding Decibelsleslie.lp2003No ratings yet

- Mechanism of Heat TransferDocument31 pagesMechanism of Heat Transferedna padreNo ratings yet

- 2 Integrated MarketingDocument13 pages2 Integrated MarketingPaula Marin CrespoNo ratings yet

- Summarised Maths Notes (Neilab Osman)Document37 pagesSummarised Maths Notes (Neilab Osman)dubravko_akmacicNo ratings yet

- Factory Test Report For OPzS 800 EED-20041724 2VDocument3 pagesFactory Test Report For OPzS 800 EED-20041724 2VmaherNo ratings yet

- Huang V Tesla State of Calif 20190430Document20 pagesHuang V Tesla State of Calif 20190430jonathan_skillings100% (1)

- A Generation of Contradictions-Unlocking Gen Z 2022 China FocusDocument25 pagesA Generation of Contradictions-Unlocking Gen Z 2022 China FocusCindy Xidan XiaoNo ratings yet

- Batt ChargerDocument2 pagesBatt Chargerdjoko witjaksonoNo ratings yet

- LETTER OF AUTHORIZATION CREDO INVEST DownloadDocument1 pageLETTER OF AUTHORIZATION CREDO INVEST DownloadEsteban Enrique Posan BalcazarNo ratings yet

- Is Iso 2692-1992Document24 pagesIs Iso 2692-1992mwasicNo ratings yet

- Malabsorption and Elimination DisordersDocument120 pagesMalabsorption and Elimination DisordersBeBs jai SelasorNo ratings yet

- AlternatorDocument3 pagesAlternatorVatsal PatelNo ratings yet

- Little ThingsDocument3 pagesLittle ThingszwartwerkerijNo ratings yet