Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Paper Dolor Abdominal PDF

Paper Dolor Abdominal PDF

Uploaded by

xurraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Paper Dolor Abdominal PDF

Paper Dolor Abdominal PDF

Uploaded by

xurraCopyright:

Available Formats

[ RESIDENT’S CASE PROBLEM ]

JASON R. RODEGHERO, PT, DPT, OCS, ATC, FAAOMPT1,2,3 • THOMAS R. DENNINGER, PT, DPT, OCS, FAAOMPT4 • MICHAEL D. ROSS, PT, DHSc5

Abdominal Pain in Physical Therapy

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at University of Massachusetts on November 10, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Practice: 3 Patient Cases

A

bdominal pain is a relatively common symptom in of unknown origin.43,59

the general population, with a reported prevalence of An underrecognized potential

source of abdominal pain, which

up to 17%,61 and 43% of patients present to primary SUPPLEMENTAL

VIDEO ONLINE is often only considered following

care clinics with complaints of abdominal pain.60 negative results of invasive test-

ing, is the musculoskeletal sys-

Abdominal pain has been associated hepatic dysfunction (TABLE 1).30 Addition- tem.44 Potential musculoskeletal sources

with myriad medical conditions, includ- ally, up to 50% of patients seen in gastro- of abdominal pain include the abdominal

Copyright © 2013 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

ing gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and enterological clinics have abdominal pain wall, psoas, lower thoracic spine (includ-

ing the discs), slipping-rib syndrome, and

myofascial components. 3,4,28,29,39,40 Injec-

! STUDY DESIGN: Resident’s case problem. physical examination findings that were concerning

tion of saline solution into various thorac-

! BACKGROUND: Abdominal pain is a common

for abdominal pain of nonmusculoskeletal origin.

Both patients with abdominal pain of musculo- ic and lumbar spinal segments has been

symptom, but not a common diagnosis, of patients

skeletal origin showed marked improvement in shown to reproduce abdominal pain.23,39,40

referred to physical therapists for examination and

pain and disability after 7 treatment sessions. Also, spinal injection was shown to elimi-

intervention. For patients with primary symptoms

The third patient was referred to her primary care nate abdominal symptoms in a subgroup

of abdominal pain, a thorough evaluation must

physician, and ultrasound examination of the

be performed to determine if symptoms are mus- of patients whose clinical examination

abdomen revealed several intrauterine masses

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

culoskeletal in nature or of a nonmusculoskeletal suggested that their symptoms were of

that were consistent with uterine fibroids. Follow-

origin that would warrant a referral to a different spinal origin. In that study,3 the levels

ing uterine fibroid embolization, the patient was

healthcare provider. This report describes the

symptom free. most often identified as the source of

management of 3 adults with primary complaints

of abdominal pain who were referred for physical ! DISCUSSION: Although not routinely man- pain, based on spinal injections, were

therapy evaluation and treatment. aged by physical therapists, abdominal pain is T11 and T12. A proposed mechanism of

! DIAGNOSIS: Two of the patients had secondary

a relatively common patient symptom that can abdominal pain of musculoskeletal origin

have several causes, both musculoskeletal and is a convergence of visceral and somatic

symptoms of hip and/or low back pain and had nonmusculoskeletal. This paper emphasizes the

previously undergone extensive medical testing for importance of physical therapists having the nec-

neural tissue into shared spinal-cord neu-

their chronic abdominal pain, without a definitive essary differential diagnostic skills to determine rons.7 This phenomenon has long been

diagnosis having been determined. A physical if patients with primary symptoms of abdominal recognized in somatic symptoms due to

therapy evaluation was conducted, and treatment, pain require physician referral or physical therapist visceral pathology, such as the referral

including manual physical therapy and exercise, intervention.

was administered to address all relative impair- pain pattern seen with angina.19 However,

ments, once the physical therapist had determined ! LEVEL OF EVIDENCE: Differential diagnosis, the opposite occurrence—the perception

that the patients’ symptoms were of musculo- level 4. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2013;43(2):44- of visceral pain secondary to musculo-

skeletal origin. The third patient included in this 53. Epub 14 January 2013. doi:10.2519/

skeletal conditions—is less recognized.

series was referred to a physical therapist with a jospt.2013.4408

Preliminary research has focused on the

diagnosis of greater trochanteric versus iliopsoas ! KEY WORDS: abdominal examination, differen-

role of the lower cervical and upper tho-

bursitis. However, the patient had abdominal pain tial diagnosis, hip, low back pain, manual physical

that was more acute in nature and a history and therapy racic spine in the production of chest pain

and improvements associated with man-

1

OSF St Joseph Medical Center, Bloomington, IL. 2Evidence In Motion, San Antonio, TX. 3Rocky Mountain University of Health Professions, Provo, UT. 4Proaxis Therapy – Spine

Center, Greenville, SC. 5Department of Physical Therapy, University of Scranton, Scranton, PA. The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or financial involvement in

any organization or entity with a direct financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. Address correspondence to Dr Jason R. Rodeghero,

Department of Rehabilitation, OSF St Joseph Medical Center, 2200 Ft Jesse Road, Suite 230, Normal, IL 61761. E-mail: Jason.r.rodeghero@osfhealthcare.org ! Copyright ©2013

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy

44 | february 2013 | volume 43 | number 2 | journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy

43-02 Rodeghero.indd 44 1/31/2013 11:59:11 AM

tive likelihood ratio [+LR] = 4.2; negative

Potential Medical Conditions likelihood ratio [–LR] = 0.39).55 If a pa-

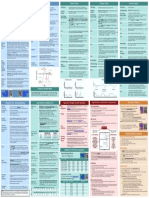

TABLE 1

Causing Abdominal Pain* tient answers no to both questions in clus-

ter 2, along with corresponding answers

Category Condition to cluster 1, there is even greater probabil-

Gastroenterologic Diarrhea ity of musculoskeletal origin (sensitivity,

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at University of Massachusetts on November 10, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Peptic ulcer 0.67; specificity, 0.96; +LR = 16.8; –LR

Gastritis = 0.34).55 Although no research has been

Diverticulitis identified that describes how commonly

Pancreatitis the Sparkes et al55 criteria are employed

Gallbladder infection by medical practitioners in routine clini-

Cholecystitis cal practice, the literature does support

Gastric impaction or obstruction their use in clinical decision making.48,65

Appendicitis Research on the use of manual physi-

Gastric cancer cal therapy in the treatment of abdomi-

Pancreatic cancer nal pain of musculoskeletal origin is

Gastrocolic fistula limited. In a recent literature search of

Paralytic ileus electronic databases using MEDLINE,

Urogenital Urinary tract disorders PubMed, OVID, and PEDro, no citations

Copyright © 2013 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

Urinary tract infection were identified that reported the use of

Renal colliculi manual physical therapy for the treat-

Ovarian cysts ment of abdominal pain; however, there

Uterine fibroids were 3 citations on the use of manual

Pelvic inflammatory disease physical therapy to treat chest pain of

Endometriosis musculoskeletal origin.14,15,56 Two papers

Kidney cancer peripherally mentioned the use of thrust

Genital cancer spinal manipulation in the management

Vascular Aortic aneurysm of these patients, without citation or fur-

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

Hepatic Liver infection ther support.3,32

Hepatitis The purpose of these case presenta-

Hepatic cirrhosis tions is to describe the clinical decision

Other Inguinal hernia making in the management of patients

Hiatal hernia presenting to outpatient physical therapy

Ascites with primary symptoms of abdominal

Peritonitis pain, including the differential diagnostic

Perineal abscess process. The clinical outcomes achieved

*Common systems that can cause abdominal pain, with conditions for each, listed in order of most to in these patients are also reported. After

least prevalent.

consultation with the Institutional Review

Board of OSF St Joseph Medical Center

ual therapy interventions.2,14,15,37,56 There have proposed that abdominal pain of in Bloomington, IL, it was determined

is little information in the literature on musculoskeletal origin may likely be as- that formal approval for publication of

the potential for abdominal pain being sociated with active movements and may the cases was not required, based on the

referred from musculoskeletal structures. be without deep abdominal tenderness. retrospective nature of the report and the

Abdominal pain of musculoskeletal Sparkes et al55 proposed 2 specific clus- provision of standard clinical care.

origin may present as sharp and focal, ters of questions that may be useful in the

cramping and aching, or deep. In com- identification of patients with abdominal DIAGNOSIS

parison, pain arising from visceral tissue musculoskeletal pain (TABLE 2). In cluster

T

is often described as dull, aching, cramp- 1, a patient answering yes to either of the hree patients were referred

ing, burning, gnawing, wave-like, and is first 2 questions and no to the third ques- for physical therapist intervention

often poorly localized. Both conditions tion suggests a high probability of abdom- in 2 different hospital-based outpa-

may present with autonomic symptoms, inal pain being of musculoskeletal origin tient physical therapy departments, all of

including nausea. Harding and Yelland32 (sensitivity, 0.67; specificity, 0.84; posi- whom presented with primary symptoms

journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 43 | number 2 | february 2013 | 45

43-02 Rodeghero.indd 45 1/31/2013 11:59:13 AM

[ RESIDENT’S CASE PROBLEM ]

patient’s Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Ques-

Abdominal Pain of Musculoskeletal tionnaire score on the physical activity

TABLE 2

Origin Question Clusters* subscale was very elevated at 24, but his

work subscale score of 12 was considered

Cluster 1:

low, possibly due to his being retired. Us-

1. “Does coughing, sneezing, or taking a deep breath make your pain feel worse?” (yes)

2. “Do activities such as bending, sitting, lifting, twisting, or turning over in bed make your pain feel worse?” (yes)

ing the abdominal pain cluster questions

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at University of Massachusetts on November 10, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

3. “Has there been any change in your bowel habit since the start of your symptoms?” (no) (TABLE 2), he answered yes to question 2

and no to question 3 of cluster 1. He an-

Cluster 2: swered no to both questions of cluster 2.

1. “Does eating certain foods make your pain feel worse?” (no)

This indicated a greater probability of his

2. “Has your weight changed since your symptoms started?” (no)

abdominal pain being musculoskeletal in

*Answering yes to either of the first 2 questions and no to the third question in cluster 1 results in a nature (sensitivity, 0.67; specificity, 0.96;

moderate probability that the patient's abdominal complaints are of musculoskeletal origin. The

probability increases to strong if both questions in cluster 2 are answered with a no. +LR = 16.8; –LR = 0.34).55

The second patient (case 2) was a

46-year-old woman who presented with

of abdominal pain and secondary symp- concerned about the persistent, more a referral from a physiatrist for pelvic/

toms of low back, pelvic, and/or hip pain. painful abdominal symptoms. He re- hip pain. She had primary symptoms of

The patients underwent a physical thera- ported making frequent trips to a large, left lower-quadrant abdominal pain and

py evaluation that included history intake well-respected teaching hospital over the secondary symptoms of anterior pelvic

Copyright © 2013 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

and physical examination. History taking previous year for exhaustive diagnostic pain. Her symptoms were described as

included a review of the patients’ medical testing from multiple specialties, includ- constant but variable in intensity, with

history and a review of systems, as well as ing gastroenterology, internal medicine, bouts of intense, sharp pain (FIGURE 1).

the presenting symptoms and functional ear-nose-throat, nuclear medicine, and She denied any symptoms in the lumbar

limitations. The physical examination orthopaedic physicians. Diagnostic test- spine or lower extremities. The abdomi-

included examination of the abdomen ing performed in the 4 months prior to nal pain had been present for 1.5 years at

and spine, and lower extremity range of his physical therapy examination includ- the time of examination. The patient had

motion, specific joint mobility, strength, ed chest radiographs, 2 computerized to- a body mass of 83 kg and was 152 cm tall.

and flexibility assessment. Reproduction mography scans, a gastric emptying test, She reported weight loss of over 36 kg in

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

of primary and/or secondary symptoms, a colonoscopy, and an endoscopy. All test- the previous 2 years, with a combination

identification of relevant musculoskeletal ing had been inconclusive, as a specific di- of diet and exercise. For the abdominal

impairments, and identification of medi- agnosis for his abdominal pain could not pain, the patient had seen multiple medi-

cal red flags that might warrant physician be determined. The patient had a body cal specialists, including specialists in

referral were the intended goals of the mass of 81.6 kg and was 185.4 cm tall. He internal medicine and gastroenterology,

history and physical examination.42 described a daily exercise regimen that and a general surgeon. The general sur-

included up to 500 abdominal crunches, geon performed an abdominal comput-

History Roman chair exercises, moderate resis- erized tomography scan and diagnosed

The first patient (case 1) was a 60-year- tance training, and cardiovascular ex- “abnormal scar tissue” that was report-

old retired man who presented with ercise. There were no reports/history of edly “attached to organs.” A laparoscopic

primary symptoms of right lower-quad- bowel/bladder issues, paresthesias, pain adhesiolysis was performed 6 months

rant abdominal pain, described as con- after eating, night pain, weight change, before the patient presented to physical

stant, variable in intensity, and deep or cancer.30 At baseline, using a numeric therapy. After the surgical procedure,

(FIGURE 1). He had secondary symptoms pain rating scale (NPRS), on which 0 rep- the symptoms reportedly worsened for

of central low back, buttock, and right resented no pain and 10 represented the a month before returning to the pre-

inner-thigh/groin pain. His abdominal worst pain possible, the patient reported surgical pain levels. The patient worked

symptoms had been present for more a 24-hour average pain of 5/10 (current full-time as an administrative assistant,

than 1 year, but the low back and right pain, 5/10; maximum pain, 7/10; mini- which required mostly desk/computer

hip/groin pain had started 5 days prior mum pain, 3/10). His score on the modi- work. She maintained her exercise rou-

to his evaluation, without a precipitat- fied Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), in tine of 45 to 60 minutes of cardiovascular

ing factor. The low back pain prompted which a higher score represented greater exercise (treadmill walking or ellipti-

the physician to refer him for physical disability, was 53%. Fear-avoidance be- cal) 4 to 5 times per week, despite the

therapy. However, despite the low back liefs were also measured using the Fear- abdominal pain, but reported that the

and hip/groin pain, the patient was more Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire.62 The intensity of her workouts had been grad-

46 | february 2013 | volume 43 | number 2 | journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy

43-02 Rodeghero.indd 4 1/31/2013 11:59:15 AM

ually decreasing due to her symptoms.

There were no reports/history of bowel/

bladder issues, paresthesias, pain after

eating, night pain, unexplained weight

change, changes in menstrual cycle, or

cancer. Her history did include 2 natu-

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at University of Massachusetts on November 10, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

ral childbirths, with the last delivery 20

years prior to the onset of her abdomi-

nal pain. From the cluster of questions in

TABLE 2, she answered yes to both ques-

tions 1 and 2 and no to question 3 on

cluster 1. She answered no to question 1

but yes to question 2 in cluster 2. This in-

dicated a likely probability of her abdom-

inal pain being musculoskeletal in nature

(sensitivity, 0.67; specificity, 0.84; +LR =

4.2; –LR = 0.39).55 It must be noted that

her weight loss (question 2 on cluster 2)

was due to a lifestyle change consisting of

Copyright © 2013 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

increased exercise and changing dietary

habits, which could have possibly skewed

the probability. At baseline, the patient

reported an average pain level over the

previous 24 hours of 6/10 on the NPRS

(current pain, 6/10; maximum pain, 8/10

when standing/walking; minimum pain,

5/10 when seated). The Lower Extremity

Functional Scale, in which a higher score Primary area of abdominal pain Case 1 Case 2 Case 3

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

indicates higher function, was used to Secondary pain complaint Case 1 Case 2 Case 3

assess her symptoms of lower abdominal

and anterior pelvic/hip pain and indicat- FIGURE 1. Body diagram of primary abdominal and secondary pain symptoms. Case 1 described his symptoms as

“constant, variable, and deep.” Case 2 described her symptoms as “constant,” with bouts of “intense, sharp pain.”

ed a score of 55/80 (69%).

Case 3 described her symptoms as “a low-grade, deep, dull ache, with intermittent cramping.”

The third patient (case 3) was a

46-year-old woman who worked full- significant past medical or surgical his- abdominal wall. When the 4 abdominal

time as an administrative assistant and tory. She denied any recent episodes of quadrants were auscultated (FIGURE 2),

who was referred to a physical therapist fatigue, fever/chills/sweats, nausea/vom- high-pitched clicks and gurgling sounds

by her primary care physician for the iting, symptoms associated with meals, were heard every 5 to 7 seconds, which

treatment of primary symptoms of right or bowel and bladder problems. She did, was considered normal.9 Palpation of the

groin and right lower-quadrant abdomi- however, report that she experienced ex- 4 abdominal quadrants with the abdom-

nal pain. The patient described her pain cessive menstrual bleeding during her inal muscles relaxed did not reveal any

as a low-grade, deep, dull ache with in- last 2 to 3 periods and that her symptoms masses or adhesion. No symptom repro-

termittent cramping (FIGURE 1). She was were worse during menstruation. The pa- duction or tenderness was provoked with

diagnosed with right greater trochanteric tient’s NPRS score was 3/10 for current palpation or percussion of the abdominal

versus iliopsoas bursitis by her physician. pain, and over the past 24 hours she re- quadrants. The patient’s blood pressure

Her symptoms had been present for the ported a maximum pain level of 5/10, a was 116/72, with a heart rate of 64 beats

past 6 weeks and were insidious in onset, minimum of 1/10, and an average of 3/10. per minute and a respiratory rate of 12

with no history of injury or trauma. She breaths per minute. Tympanic tempera-

was unable to identify aggravating factors Examination ture was normal at 98.6°. At this point,

and reported taking nonsteroidal anti-in- Case 1 Visual inspection of the patient’s a more comprehensive musculoskeletal

flammatory medication, which decreased abdomen did not reveal any concerns, examination was initiated.

her symptoms. The patient was not tak- such as skin abnormalities, abdominal Visual inspection of standing posture

ing any other medications and had no masses, or abnormal movement of the revealed a left lateral shift.16 As measured

journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 43 | number 2 | february 2013 | 47

43-02 Rodeghero.indd 4 1/31/2013 11:59:1 AM

[ RESIDENT’S CASE PROBLEM ]

on a bubble inclinometer, standing lum- the lumbar spine.22,26 The probability of

bar extension was limited to 5°, with re- successfully addressing his low back pain

production of the patient’s low back and was 92%, based on a +LR of 13.2, when

groin pain.52 Active lateral pelvic transla- applying the lumbar-manipulation clini-

tion in either direction did not increase or cal prediction rule.12 Other impairments

decrease any of the patient’s symptoms. to be addressed with treatment included

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at University of Massachusetts on November 10, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

There were no limitations of motion and flexibility deficits, limitation of spinal ex-

reproduction of symptoms with spinal tension mobility, and spinal strengthen-

flexion or sidebending, and no aberrant ing due to the positive prone instability

movements were observed.34 Neurologi- test and the typical use of exercise as an

cal screening, which included myotome, adjunct to treatment using manipulation

dermatome, upper motor neuron (Babin- techniques.22

ski and clonus), and sensory testing, Case 2 Visual inspection of the patient’s

was considered normal for both lower abdomen did not reveal concerns such as

extremities. Visual inspection of seated skin abnormalities, abdominal masses, or

posture indicated a normal posture, in- abnormal movement of the abdominal

cluding no signs of a lateral shift and level wall. She did have prominent adipose

iliac crests. Slump testing for neurody- tissue throughout the abdomen, along

namic assessment did not reproduce any FIGURE 2. Auscultation of abdominal quadrants. with redundant skin, likely from the

Copyright © 2013 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

symptoms.33 In supine, provocative hip Auscultation of each abdominal quadrant is weight loss. Normal bowel sounds (high-

and sacroiliac special tests were nega- performed using a stethoscope. High-pitched clicks pitched clicks and gurgling sounds every

and gurgling sounds heard every 5 to 7 seconds are

tive.41,64 Straight leg raise and crossed considered normal. Abbreviations: LLQ, left lower

5 to 7 seconds) were noted during aus-

straight leg raise tests were negative bi- quadrant; LUQ, left upper quadrant; RLQ, right lower cultation (FIGURE 2), and percussion did

laterally (75° right and 90° left).18,25 Flex- quadrant; RUQ, right upper quadrant. Published not reproduce any symptoms.9 Palpation

ibility screening of the lower extremities with permission from Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, throughout the abdominal quadrants

was performed, demonstrating marked eds. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and with the abdominal muscles relaxed did

Laboratory Examinations. 3rd edition. Boston, MA:

deficits of the right hamstrings, hip flex- Butterworth; 1990. Copyright ©1990 Elsevier.

not identify any abnormal masses. Ten-

ors, and rectus femoris.25 Furthermore, derness was provoked with deep palpa-

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

passive flexibility testing of both the right ity present from T12 to L3, with spring tion in the mid–lower-left abdominal

iliopsoas and rectus femoris in the Thom- testing for L1, L2, and L3 reproducing quadrant, which was described as being

as test position reproduced the primary the abdominal, low back, and hip/groin/ similar to her pain. Her blood pressure

symptoms of abdominal pain in addi- buttock pain. Positional testing of prone was 124/80, with a heart rate of 72 beats

tion to his low back pain.24 In prone, hip on elbows increased all symptoms, in- per minute and a respiratory rate of 14

range of motion assessed with an incli- cluding abdominal, back, and hip/groin/ breaths per minute. Tympanic tempera-

nometer was limited in extension on the buttock pain. Repeated extension testing ture was normal at 98.8°. At this point,

right (10°) compared to the left (20°), but was not performed. Given pain repro- a more comprehensive musculoskeletal

was normal for internal rotation bilater- duction with spring testing on L1, L2, examination was initiated, which focused

ally (30°-35°).5 Hip flexion in supine did and L3, the prone instability test was on the lumbopelvic and hip region.

not alter any of the patient’s symptoms. performed.34 The prone instability test In standing, the patient demonstrat-

Prone flexibility testing of the iliopsoas was considered positive, as symptoms ed increased lumbar lordosis, with no

and rectus femoris again reproduced the were abolished during testing.25,34 Based other postural abnormalities.25 Active

primary symptoms of abdominal pain. on the proposed treatment-based-clas- spinal motion was without limitation

Spring testing (anteroposterior pressure) sification system for low back pain, the in any direction, but her primary pain

for mobility assessment and pain provo- patient was considered likely to respond was reproduced with end-range exten-

cation was performed centrally over the to a treatment approach that included sion.25,52 Special tests of the hip and pro-

spinous process and unilaterally over the spinal manipulation, based on the follow- vocative sacroiliac joint tests were all

facet joints from T6 to S1.1,35 Spinal mo- ing variables: acute low back pain of less negative.18,25,41 Primary abdominal pain

bility for each segment was classified as than 16 days in duration, 1 hip with 35° symptoms were reproduced (NPRS, 8/10)

normal, hypomobile, or hypermobile. 35 or greater of internal rotation, no symp- with flexibility assessment of the iliopsoas

Normal mobility and no symptoms were toms below the knee, Fear-Avoidance muscle in supine and prone.25 Left hip

reproduced with testing from T6 to T11 Beliefs Questionnaire work subscale extension was limited to 10°, at which

and from L4 to S1. There was hypomobil- score less than 19, and hypomobility of point the abdominal pain increased and

48 | february 2013 | volume 43 | number 2 | journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy

43-02 Rodeghero.indd 4 1/31/2013 11:59:20 AM

the patient resisted any further extension. atic palpation in each of the 4 abdominal back pain. The patient was instructed on

The lumbar spine was assessed further quadrants provoked an increase in the home exercises, including self-stretching

with spring testing (central and unilat- patient’s symptoms with palpation of the (hip flexors) and self-mobilization of

eral) from T10 to S1.25,42 Hypermobility right lower abdominal quadrant. the spine (sidelying rotation and spinal

was detected in the middle lumbar spine extension). The patient was advised to

(L2-L4), with hypomobility in the lower Interventions temporarily discontinue his daily abdom-

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at University of Massachusetts on November 10, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

lumbar spine (L4-S1). Primary abdomi- Case 1 The patient received 7 physi- inal-crunch exercise routine.

nal pain was not reproduced with spring cal therapy treatment sessions over the The second treatment session was

testing of any vertebral level. Spring test- course of 4 weeks. Treatment was im- conducted 4 days later. The patient’s

ing of the L5-S1 vertebral level repro- mediately initiated after the examina- abdominal pain remained decreased to

duced her low back pain. Manual muscle tion and included thrust mobilization/ 3/10 since his initial treatment. His ODI

testing was performed on the hip muscu- manipulation targeting the upper lum- score had improved to 28%, and his re-

lature and indicated 4/5 weakness of the bar region.42 A high-velocity, end-range, ported global rating of change (GROC)

hip abductors and external rotators bilat- left rotational force to the lower lumbar score was +4 (moderately better). There

erally. Resisted hip flexion caused signifi- spine on the upper lumbar spine, in a was no lateral shift present, and he felt

cant abdominal pain reproduction at the left sidelying, right lower thoracic lum- able to “stand up straighter.” The hip/

initial application of resistance. She was bar sidebent position, was performed, buttock/groin pain was now described

unable to maintain an active sit-up posi- due to this being the more limited and as “intermittent” and seemed to only

tion for more than 3 seconds, indicating painful side.17,42 Spring testing was reas- occur upon standing/walking after pro-

Copyright © 2013 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

the likelihood of abdominal weakness.25 sessed and mobility appeared normal, longed sitting. Improvements in spinal

At this point, the initial hypothesis of and no low back pain was reproduced and hip extension range of motion were

iliopsoas muscle involvement was deter- with testing. But abdominal pain was both maintained from his first treatment

mined to be most likely, and treatment still present during testing, so graded session. Hypomobility and an increase

was initiated to address all relative local (grades 3 and 4) mobilizations were per- in symptoms (low back and abdominal)

and regional impairments. formed unilaterally from T12 to L3 (seg- were still noted when performing central

Case 3 The patient’s blood pressure was ments correlating with abdominal pain and right unilateral spring testing at the

measured at 129/78, with a heart rate of provocation) using 3 bouts of 30 seconds L2-3 vertebral level. Abdominal pain was

72 beats per minute and a respiratory at each level.42 Abdominal symptoms at still reproduced with stretching of the

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

rate of 13 breaths per minute. Her tym- rest decreased by 50%, per patient report, iliopsoas but not of the rectus femoris,

panic temperature was 98.0°. Physical following mobilizations. Following thrust both assessed in the Thomas test posi-

examination revealed a normal, nonan- mobilization/manipulation, the lateral tion. Flexibility impairments of the ilio-

talgic gait and full range of motion of the shift was no longer present. Treatment psoas remained, but the rectus femoris

lumbar spine and bilateral hips, without then focused on flexibility impairments no longer appeared limited. Treatment

changes in the patient’s symptoms. Neu- that reproduced his abdominal pain. Hip during this session was similar to that

rological screening that included lower extension range of motion was treated provided during the first treatment ses-

extremity myotome, dermatome, and in supine, with contract-relax stretch- sion, consisting of hip flexor stretching

deep tendon reflex testing was negative ing techniques in the Thomas test posi- plus thrust and nonthrust spinal mobili-

bilaterally. Bilateral straight leg raise tion.21,24,49,53,54 Stretches were held at the zation/manipulation applied to the upper

and prone knee bend testing was nega- first point of resistance/tightness, which lumbar region.

tive bilaterally. Middle-to-lower tho- was prior to aggravation of abdominal At his third session, the patient re-

racic and lumbar spring testing through pain. Each stretch was held for 20 to ported that his abdominal pain re-

posterior-to-anterior pressures over the 30 seconds following gentle contrac- mained unchanged at 3/10 on the NPRS.

spinous processes was normal for mobil- tion of the specific muscle (hip flexion His low back pain was reportedly abol-

ity and did not increase or provoke the or knee extension) and repeated 3 to 4 ished (0/10). The physical examination

patient’s symptoms. Visual inspection of times, progressing further into the allow- revealed continued limitations of flex-

the patient’s abdomen did not reveal any able range.21 Following the intervention ibility in the right hip. Prone hip exten-

concerns, such as skin abnormalities, ab- on day 1, the patient reported that his sion, used to assess iliopsoas flexibility,

dominal masses, or abnormal movement current abdominal pain had decreased was still limited and reproduced his ab-

of the abdominal wall. Normal bowel to 3/10. He demonstrated 15° of spinal dominal symptoms. Limitations with

sounds (high-pitched clicks and gurgling extension without peripheralization of spinal mobility were no longer present

sounds every 5 to 7 seconds) were noted symptoms to the groin and 15° of right in the upper lumbar spine, and abdomi-

during auscultation (FIGURE 2). System- hip extension without abdominal or low nal symptoms were not reproduced with

journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 43 | number 2 | february 2013 | 49

43-02 Rodeghero.indd 49 1/31/2013 11:59:23 AM

[ RESIDENT’S CASE PROBLEM ]

spring testing. Interventions addressing

remaining flexibility and strengthening TABLE 3 Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

of hip extensors and lumbar extensors

due to the increased range of motion were

performed with progression of care ad- Case 1 Case 2 Case 3*

ministered over sessions 3 to 7. Interven- Baseline abdominal pain† 5/10 6/10 3/10

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at University of Massachusetts on November 10, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

tions performed included cardiovascular Discharge abdominal pain† 0/10 0/10 NA

warm-up, self-stretching, weight-bearing Baseline disability score 53%‡ 55/80§ NA

and non–weight-bearing lower extremity Discharge disability score 0%‡ 70/80§ NA

strengthening, and instruction in a home Global rating of change score +7 (a very great deal better) +7 (a very great deal better) NA

exercise program to address the relevant Abbreviation: NA, not assessed.

impairments. *Outcome measures were not collected, as patient was only seen once by the physical therapist.

†

Measured as average pain in the past 24 hours with a numeric pain rating scale, on which 0

Case 2 This patient was treated for a represented no pain and 10 represented the worst pain possible.

total of 7 sessions over the course of 6 ‡

Measured with the Oswestry Disability Index, on which lower scores indicated better outcomes.

§

weeks. The initial treatment consisted of Measured with the Lower Extremity Functional Scale, on which higher scores indicated better

outcomes.

contract-relax stretching techniques tar-

geting the hip flexors. In addition, a high-

velocity, end-range, left rotational thrust in self-mobilizations, along with pirifor- toms worse during menstruation), an in-

technique, with the force applied to the mis stretches to address noted flexibility ability to reproduce the patient’s primary

Copyright © 2013 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

left anterior pelvis in a supine, left tho- impairments. No pain or restrictions were symptoms with evaluation of the hip and

racolumbar sidebent position, was per- noted with spring testing of the lumbar lumbar spine, and a reproduction of the

formed.53,54 The patient was instructed in spine, so no further manipulative inter- patient’s symptoms with abdominal pal-

a home exercise program that consisted ventions of this region were performed. pation.8,29,50,52 Therefore, no physical ther-

of self-stretching (hip flexor stretch using The patient was reassessed prior to apy interventions were provided and the

the Thomas test position), active range of her third treatment session. Passive hip findings were discussed with the patient’s

motion for the hip (straight leg raises), extension was no longer limited and did primary care physician, who decided to

and active range of motion for the lum- not further aggravate her pain. Resisted re-evaluate the patient.

bar spine (pelvic rocking). Between the hip flexion was no longer painful, but

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

first and second treatment sessions, she strength was still limited at 4/5. The pain Outcomes

reported a decrease in pain to 4/10 with rating at that time, assessed using the Pain and disability scores were consis-

prone hip extension, and there was no NPRS, was 2/10, with a 24-hour maxi- tently collected throughout the duration

pain with end-range spinal extension. mum rating of 4/10 and a minimum rat- of care (TABLE 3). The NPRS was used with

At her next session, the patient noted ing of 1/10. The interventions provided all 3 patients. The ODI was used with 1

significant improvements in pain levels at the remaining treatment sessions con- patient, due to regional and secondary

and an increased ability to stand and sisted of therapeutic exercise that focused symptoms of low back pain that appeared

walk with less pain. She continued to have on general strengthening of the spine, ab- to be associated with abdominal pain.

limitations and abdominal pain with hip domen, and hip/pelvis. At each session, The Lower Extremity Functional Scale

extension, but her range of motion had she completed cardiovascular exercise, was used with the other patient due to

improved to 20°. Treatment addressing self-stretching, and progressive resisted secondary symptoms of lower extremity

hip flexor flexibility was continued, along strengthening, consisting of weight-bear- pain that appeared to be associated with

with more specific manual therapy to the ing and non–weight-bearing resistance abdominal pain. No specific abdominal

hip. The combination of hip flexion, ab- exercises. A home exercise program was pain outcome measurement was used, as

duction, and external rotation assessed in prescribed to address the identified re- the authors knew of no valid tool at the

a prone position was considered to be lim- maining impairments. time of treatment. The GROC was used

ited and produced discomfort in the hip Case 3 Based on the history and exami- with the first 2 patients to assess their

and abdomen. To address this perceived nation findings, there was concern that perceived level of improvement.6,13,27,36

deficit, three 30-second bouts of poste- the patient’s abdominal pain was of non- Case 1 At his final treatment session, the

rior-to-anterior nonthrust mobilizations musculoskeletal origin. More specifically, patient reported 0/10 abdominal and low

(grade 3) were performed in prone, with these concerns were based on an insidi- back pain. He was also no longer having

the hip positioned in flexion, abduction, ous onset of symptoms, a lack of aggra- any symptoms in the buttock and hip

and external rotation (figure-of-four posi- vating factors that were consistent with region. The ODI was completed, and a

tion in prone).42 She was also instructed pain of musculoskeletal origin (eg, symp- score of 0% (0/50) indicated the absence

50 | february 2013 | volume 43 | number 2 | journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy

43-02 Rodeghero.indd 50 1/31/2013 11:59:2 AM

of disability. The patient reported being a the responsibility of physical therapists standing history of significant abdominal

very great deal better (+7) on the GROC. to perform a good initial evaluation and pain. Each patient had undergone ex-

Case 2 At her final appointment, the pa- monitor patients over time to identify tensive diagnostic testing from multiple

tient reported 0/10 to 1/10 symptoms of those who may need to be referred, while physician specialties, without a medical

abdominal pain. She was no longer hav- being careful to avoid excessive referral. diagnosis being determined. Secondary

ing any anterior pelvic pain. The Lower Primary symptoms of abdominal pain symptoms of low back pain and/or hip

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at University of Massachusetts on November 10, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Extremity Functional Scale was complet- are not a common presentation in physi- pain ultimately prompted a referral to a

ed, and a score of 88% (70/80) indicated cal therapy clinics. Low back pain, how- physical therapist. The physical therapy

significantly improved function. On the ever, is the most common reason patients examination, which included a compre-

GROC, the patient reported being a very receive treatment from a physical thera- hensive abdominal examination, identi-

great deal better (+7). pist.8,38 Screening of the gastrointestinal fied impairments in the lumbar spine and

Case 3 Laboratory testing (complete and genitourinary systems is considered hips, along with reproduction of the pri-

blood count, metabolic panel) was or- to be an important and vital component mary abdominal pain with specific tests

dered, and all values were within normal of the physical therapy examination for of the lumbar and hip region. No red flags

limits. Ultrasound examination of the patients with low back pain and, obvi- were noted, which eliminated the need

abdomen revealed several intrauterine ously, abdominal pain.18,30 In a previous- for further medical consultation.

masses that were consistent with uterine ly published case report, Stowell et al57 The psoas muscle appeared to play

fibroids, the largest measuring 5.5 cm at presented and discussed the differential an important role in the presentation

its point of greatest dimension. The ul- diagnostic process for the examination of symptoms for both patients, with the

Copyright © 2013 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

trasound findings were confirmed with of the abdomen in patients presenting to pain in both cases decreasing as psoas

magnetic resonance imaging. The patient physical therapy with symptoms of low muscle flexibility improved. The psoas

subsequently underwent uterine fibroid back pain. The patient in that report was muscle has been described as a potential

embolization,31 which results in occlusion referred to an emergency department source of abdominal pain, but usually

of fibroid vessels and subsequent isch- following physical therapy examination when there is an abscess or in the pres-

emic restriction of the fibroid. The patient and was diagnosed with severe intesti- ence of appendicitis.46,63 Impairments in

was contacted 1 year after the procedure nal constipation from decreased colonic lumbar spine mobility were also identi-

and reported that she was symptom free. motility due to opioid analgesic medica- fied as potential sources of abdominal

tion. He received medical treatment and pain, most likely due to somatic referral.

DISCUSSION

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

subsequently resumed physical therapy Previous research on referral patterns

to address persistent low back pain.57 of spinal structures has demonstrated

P

hysical therapists regularly Mechelli et al45 published a case report that tissues of the thoracic and lumbar

perform screening examinations of in which a patient with primary com- spine can refer pain to the abdominal

their patients to rule out more seri- plaints of low back pain was examined by cavity.11,23,40 This appears to be consistent

ous, pathological conditions. In a recent a physical therapist. The abdominal ex- with the clinical scenario presented by

review of published case reports, Bois- amination indicated the possibility of an the first patient, whose abdominal symp-

sonnault and Ross10 reviewed 78 pub- abdominal aortic aneurysm, which was toms, reproduced with segmental spring

lished cases in which a physical therapist later confirmed on ultrasound and a com- testing of the upper lumbar spine, pro-

referred patients to physicians and a puterized tomography scan. That patient gressively decreased as his lumbar spine

medical diagnosis was subsequently iden- was appropriately referred to a medical mobility improved. In this patient, all

tified. Published case reports have dem- specialist immediately for proper care. impairments identified in the physical

onstrated the ability of physical therapists Similar to the third patient presented therapy examination that were directly

to perform a screening examination for in the current report, these 2 previously causing or could potentially contribute

detection of conditions such as cervi- published cases illustrate the more com- to the nonacute abdominal pain were

cal fracture,47,50 deep vein thrombosis,58 monly recognized scenario of low back addressed. As primary and relative im-

abdominal aortic aneurysms,45,57 cauda pain associated with potentially serious pairments were treated, abdominal pain

equina syndrome,20 and cancer.51 We are nonmusculoskeletal conditions. and secondary symptoms (low back pain

unaware of studies that have reported on In contrast, the first 2 cases presented and hip pain) all resolved. Although a

the number of patients referred to physi- in this report illustrate a different scenar- cause-and-effect relationship between

cians who did not have a medical diag- io, in which abdominal pain is associated the interventions provided and the reso-

nosis, potentially indicating overreferral, with musculoskeletal structures. The first lution of abdominal and other symptoms

or studies reporting on cases that should 2 patients described in this report were cannot be established with absolute cer-

have been referred but were not. It is unique in that they presented with a long- tainty in these 2 cases, the long-term du-

journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 43 | number 2 | february 2013 | 51

43-02 Rodeghero.indd 51 1/31/2013 11:59:2 AM

[ RESIDENT’S CASE PROBLEM ]

ration of the constant symptoms (more uterine fibroid embolization. Uterine syndrome. J Natl Med Assoc. 1979;71:863-865.

than 1 year), combined with resolution of fibroids are the most common type of 5. Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Bohnen AM, Ramlal R,

symptoms over a relatively short period benign tumors of the female reproduc- Ridderikhoff J, Verhaar JA, Prins A. Comparison

between two devices for measuring hip joint mo-

(6 weeks), supports the effectiveness of tive system that occur in premenopausal

tions. Clin Rehabil. 1998;12:497-505.

the care provided. women, and their highest incidence is in 6. Binkley JM, Stratford PW, Lott SA, Riddle DL. The

For the first 2 patients described in women in their mid-40s.31 The conse- Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS): scale

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at University of Massachusetts on November 10, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

this report, no red flags were noted at the quences of a delayed/missed diagnosis of development, measurement properties, and

clinical application. North American Orthopaedic

time of the initial physical therapist evalu- uterine fibroids are not completely clear,

Rehabilitation Research Network. Phys Ther.

ation, and the patients had already been but uterine fibroids are often undiag- 1999;79:371-383.

extensively tested for nonmusculoskeletal nosed, and the majority of women with 7. Bogduk N. Mechanisms of musculoskeletal pain.

sources of pain, which eliminated the need uterine fibroids are often asymptom- Australas Musculoskelet Med. 2006;11:6-18.

8. Boissonnault WG. Prevalence of comorbid condi-

for medical consultation. In addition, both atic.31 As uterine fibroids grow, however,

tions, surgeries, and medication use in a physical

patients responded favorably in a brief they cause enlargement of the uterus, therapy outpatient population: a multicentered

period to physical therapist intervention, which may be associated with pelvic pain study. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1999;29:506-

which further supported the diagnosis of and pressure.31 Other symptoms associ- 519; discussion 520-525.

9. Boissonnault WG. Primary Care for the Physical

a musculoskeletal source of abdominal ated with uterine fibroids may include

Therapist: Examination and Triage. 2nd ed. St

pain. A lack of response to intervention menorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, dyspareu- Louis, MO: Elsevier/Saunders; 2011.

can be an important finding in identifying nia, and urinary difficulties.31 Following 10. Boissonnault WG, Ross MD. Physical therapists

those patients with potentially serious dis- uterine fibroid embolization, the fibroids referring patients to physicians: a review of case

Copyright © 2013 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

reports and series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther.

orders that require medical referral.10 We shrink over the course of several months

2012;42:446-454. http://dx.doi.org/10.2519/

therefore recommend that physical thera- to years, often with subsequent reduction jospt.2012.3890

pists periodically assess patient progress of the associated symptoms, as occurred 11. Cervero F, Connell LA. Distribution of somatic

through the course of care, using reliable with this patient.31 and visceral primary afferent fibres within the

thoracic spinal cord of the cat. J Comp Neurol.

and valid measures. If clinically meaning-

1984;230:88-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/

ful improvements are not seen within a CONCLUSION cne.902300108

reasonable period (4-6 weeks), medical 12. Childs JD, Fritz JM, Flynn TW, et al. A clinical

A

consultation should be initiated. lthough not routinely managed prediction rule to identify patients with low

back pain most likely to benefit from spinal

The third patient described in this by physical therapists, abdominal

manipulation: a validation study. Ann Intern Med.

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

report was referred by her primary care pain is a relatively common patient 2004;141:920-928.

physician for a primary complaint of symptom that can have several causes, 13. Childs JD, Piva SR, Fritz JM. Responsiveness of the

right groin and right lower-quadrant including both musculoskeletal and non- numeric pain rating scale in patients with low back

pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:1331-1334.

abdominal pain and an associated diag- musculoskeletal origins. In this paper, we

14. Christensen HW, Vach W, Gichangi A, Manniche

nosis of right greater trochanteric versus described 2 patients with primary symp- C, Haghfelt T, Høilund-Carlsen PF. Cervicothoracic

iliopsoas bursitis. However, an insidious toms of abdominal pain who responded angina identified by case history and palpation

onset of symptoms, a lack of aggravating well to physical therapy intervention di- findings in patients with stable angina pectoris.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28:303-311.

factors consistent with pain of musculo- rected to the lumbar and hip region, and

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.04.002

skeletal origin, an inability to reproduce 1 patient who presented with red flags re- 15. Christensen HW, Vach W, Gichangi A, Manniche

the patient’s primary symptoms with quiring referral to a physician. ! C, Haghfelt T, Høilund-Carlsen PF. Manual therapy

evaluation of the hip and lumbar spine, for patients with stable angina pectoris: a nonran-

domized open prospective trial. J Manipulative

and a reproduction of the patient’s symp-

Physiol Ther. 2005;28:654-661. http://dx.doi.

toms with abdominal palpation were of REFERENCES

org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.09.018

concern. Although such a patient history 16. Clare HA, Adams R, Maher CG. Reliability of detec-

1. Abbott JH, Flynn TW, Fritz JM, Hing WA, Reid D,

and physical examination findings were tion of lumbar lateral shift. J Manipulative Physiol

Whitman JM. Manual physical assessment of Ther. 2003;26:476-480. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

not necessarily diagnostic in nature, spinal segmental motion: intent and validity. Man S0161-4754(03)00104-0

they did provide a cluster of signs and Ther. 2009;14:36-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. 17. Cleland JA, Fritz JM, Kulig K, et al. Comparison of

symptoms suggestive of a nonmuscu- math.2007.09.011 the effectiveness of three manual physical therapy

2. Arroyo JF, Jolliet P, Junod AF. Costovertebral joint techniques in a subgroup of patients with low

loskeletal cause of abdominal pain that

dysfunction: another misdiagnosed cause of atypi- back pain who satisfy a clinical prediction rule: a

necessitated physician referral. After ul- cal chest pain. Postgrad Med J. 1992;68:655-659. randomized clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976).

trasound examination of the abdomen 3. Ashby EC. Abdominal pain of spinal origin. 2009;34:2720-2729. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/

revealed several intrauterine masses that Value of intercostal block. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. BRS.0b013e3181b48809

were consistent with uterine fibroids, the 1977;59:242-246. 18. Cook CE, Hegedus EJ. Orthopedic Physical Exami-

4. Bass J, Jr., Pan HC, Fegelman RH. Slipping rib nation Tests: An Evidence-Based Approach. 2nd

third patient in this report underwent

52 | february 2013 | volume 43 | number 2 | journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy

43-02 Rodeghero.indd 52 1/31/2013 11:59:31 AM

ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall; cally important difference. Control Clin Trials. 53. Shadmehr A, Hadian MR, Naiemi SS, Jalaie S.

2012. 1989;10:407-415. Hamstring flexibility in young women following

19. Crea F, Gaspardone A. New look to an old 37. Jensen S. Musculoskeletal causes of chest pain. passive stretch and muscle energy technique. J

symptom: angina pectoris. Circulation. Aust Fam Physician. 2001;30:834-839. Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2009;22:143-148.

1997;96:3766-3773. 38. Jette AM, Smith K, Haley SM, Davis KD. Physical http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/BMR-2009-0227

20. Crowell MS, Gill NW. Medical screening and evacu- therapy episodes of care for patients with low 54. Smith M, Fryer G. A comparison of two muscle

ation: cauda equina syndrome in a combat zone. back pain. Phys Ther. 1994;74:101-110; discussion energy techniques for increasing flexibility of the

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39:541-549. 110-115.

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at University of Massachusetts on November 10, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

hamstring muscle group. J Bodyw Mov Ther.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2009.2999 39. Kellgren JH. Observations on referred pain arising 2008;12:312-317. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.

21. Decoster LC, Cleland J, Altieri C, Russell P. The ef- from muscle. Clin Sci. 1938;3:175-190. jbmt.2008.06.011

fects of hamstring stretching on range of motion: a 40. Kellgren JH. On the distribution of pain arising 55. Sparkes V, Prevost AT, Hunter JO. Derivation and

systematic literature review. J Orthop Sports Phys from deep somatic structures with charts of seg- identification of questions that act as predictors

Ther. 2005;35:377-387. http://dx.doi.org/10.2519/ mental pain areas. Clin Sci. 1939;4:35-46. of abdominal pain of musculoskeletal origin. Eur J

jospt.2005.2012 41. Laslett M, Aprill CN, McDonald B, Young SB.

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:1021-1027. http://

22. Delitto A, George SZ, Van Dillen LR, et al. Low back Diagnosis of sacroiliac joint pain: validity of

dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.meg.0000059173.46867.0c

pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42:A1-A57. individual provocation tests and composites of

56. Stochkendahl MJ, Christensen HW, Vach W, Høi-

http://dx.doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2012.0301 tests. Man Ther. 2005;10:207-218. http://dx.doi.

lund-Carlsen PF, Haghfelt T, Hartvigsen J. Chiro-

23. Feinstein B, Langton JN, Jameson RM, Schiller F. org/10.1016/j.math.2005.01.003

practic treatment vs self-management in patients

Experiments on pain referred from deep somatic 42. Maitland G, Hengeveld E, Banks K, English K. Mait-

tissues. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1954;36-A:981-997. with acute chest pain: a randomized controlled

land’s Vertebral Manipulation. 6th ed. Waltham,

24. Ferber R, Kendall KD, McElroy L. Normative and MA: Elsevier/Butterworth-Heinemann; 2001. trial of patients without acute coronary syndrome.

critical criteria for iliotibial band and iliopsoas 43. Manning AP, Thompson WG, Heaton KW, Morris J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012;35:7-17. http://

muscle flexibility. J Athl Train. 2010;45:344-348. AF. Towards positive diagnosis of the irritable dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2010.11.004

25. Flynn TW, Cleland JA, Whitman JM. Users’ Guide bowel. Br Med J. 1978;2:653-654. 57. Stowell T, Cioffredi W, Greiner A, Cleland J. Abdom-

Copyright © 2013 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

to the Musculoskeletal Examination: Fundamen- 44. McGarrity TJ, Peters DJ, Thompson C, McGarrity inal differential diagnosis in a patient referred to a

tals for the Evidence-Based Clinician. Louisville, SJ. Outcome of patients with chronic abdominal physical therapy clinic for low back pain. J Orthop

KY: Evidence In Motion; 2008. pain referred to chronic pain clinic. Am J Gas- Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35:755-764. http://dx.doi.

26. Fritz JM, Cleland JA, Childs JD. Subgrouping troenterol. 2000;95:1812-1816. http://dx.doi. org/10.2519/jospt.2005.2052

patients with low back pain: evolution of a clas- org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02170.x 58. Theiss JL, Fink ML, Gerber JP. Deep vein throm-

sification approach to physical therapy. J Orthop 45. Mechelli F, Preboski Z, Boissonnault WG. Differ- bosis in a young marathon athlete. J Orthop

Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37:290-302. http://dx.doi. ential diagnosis of a patient referred to physical Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41:942-947. http://dx.doi.

org/10.2519/jospt.2007.2498 therapy with low back pain: abdominal aortic an- org/10.2519/jospt.2011.3823

27. Fritz JM, Irrgang JJ. A comparison of a modified eurysm. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38:551- 59. Thompson WG, Heaton KW. Functional bowel

Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire 557. http://dx.doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2008.2719 disorders in apparently healthy people. Gastroen-

and the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale. Phys 46. Melissas J, Romanos J, de Bree E, Schoretsanitis terology. 1980;79:283-288.

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

Ther. 2001;81:776-788. G, Askoxylakis J, Tsiftsis DD. Primary psoas 60. Vandvik PO, Kristensen P, Aabakken L, Farup PG.

28. Gallegos NC, Hobsley M. Abdominal wall pain: an abscess. Report of three cases. Acta Chir Belg. Abdominal complaints in general practice. Scand

alternative diagnosis. Br J Surg. 1990;77:1167-1170. 2002;102:114-117. J Prim Health Care. 2004;22:157-162. http://

29. Gallegos NC, Hobsley M. Recognition and treat- 47. Mintken PE, Metrick L, Flynn TW. Upper cervical dx.doi.org/10.1080/02813430410006503

ment of abdominal wall pain. J R Soc Med. ligament testing in a patient with os odontoideum 61. Von Korff M, Dworkin SF, Le Resche L, Kruger A.

1989;82:343-344. presenting with headaches. J Orthop Sports Phys An epidemiologic comparison of pain complaints.

30. Goodman CC, Snyder TEK. Differential Diagnosis Ther. 2008;38:465-475. http://dx.doi.org/10.2519/ Pain. 1988;32:173-183.

in Physical Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. jospt.2008.2747

62. Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D,

Saunders Company; 2000. 48. Otero W, Ruiz X, Otero E, Gómez M, Pineda LF,

Main CJ. A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire

31. Goodwin SC, Spies JB. Uterine fibroid emboliza- Arbeláez V. Chronic abdominal wall pain: an un-

(FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs

tion. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:690-697. recognized entity with great impact in the clinical

in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain.

32. Harding G, Yelland M. Back, chest and abdominal practice. Rev Col Gastroenterol. 2007;22:261-271.

1993;52:157-168.

pain – is it spinal referred pain? Aust Fam Physi- 49. Roberts JM, Wilson K. Effect of stretching duration

63. Wagner JM, McKinney WP, Carpenter JL.

cian. 2007;36:422-423, 425, 427-429. on active and passive range of motion in the lower

33. Herrington L, Bendix K, Cornwell C, Fielden N, extremity. Br J Sports Med. 1999;33:259-263. Does this patient have appendicitis? JAMA.

Hankey K. What is the normal response to struc- 50. Ross MD, Cheeks JM. Clinical decision making as- 1996;276:1589-1594.

tural differentiation within the slump and straight sociated with an undetected odontoid fracture in 64. Wang WG, Yue DB, Zhang NF, Hong W, Li ZR. Clini-

leg raise tests? Man Ther. 2008;13:289-294. an older individual referred to physical therapy for cal diagnosis and arthroscopic treatment of ac-

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2007.01.013 the treatment of neck pain. J Orthop Sports Phys etabular labral tears. Orthop Surg. 2011;3:28-34.

34. Hicks GE, Fritz JM, Delitto A, McGill SM. Prelimi- Ther. 2008;38:418-424. http://dx.doi.org/10.2519/ http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1757-7861.2010.00121.x

nary development of a clinical prediction rule for jospt.2008.2687 65. Wiesner M, Naylor SJ, Copping A, et al.

determining which patients with low back pain will 51. Ryder M, Deyle GD. Differential diagnosis of fibular Symptom classification in irritable bowel

respond to a stabilization exercise program. Arch pain in a patient with a history of breast cancer. syndrome as a guide to treatment. Scand J

Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1753-1762. http:// J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39:230. http:// Gastroenterol. 2009;44:796-803. http://dx.doi.

dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2005.03.033 dx.doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2009.0403 org/10.1080/00365520902964705

35. Huijbregts PA. Spinal motion palpation: a re- 52. Saur PM, Ensink FB, Frese K, Seeger D, Hilde-

view of reliability studies. J Man Manip Ther. brandt J. Lumbar range of motion: reliability and

@ MORE INFORMATION

2002;10:24-39. validity of the inclinometer technique in the clini-

36. Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement cal measurement of trunk flexibility. Spine (Phila

of health status. Ascertaining the minimal clini- Pa 1976). 1996;21:1332-1338. WWW.JOSPT.ORG

journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 43 | number 2 | february 2013 | 53

43-02 Rodeghero.indd 53 1/31/2013 11:59:33 AM

ERRATUM

I

n the February 2013 issue of JOSPT, Gibbons and Tehan1). The information

the article “Abdominal Pain in Physical pertaining to uterine fibroid embolization REFERENCES

Therapy Practice: 3 Patient Cases” by on pages 51 and 52 is now correctly attrib-

Rodeghero et al (J Orthop Sports Phys uted to Goodwin and Spies,3 and previous 1. Gibbons P, Tehan P. Manipulation of the Spine,

Ther 2013;43(2):44-53. Epub 14 January references on page 49 to Gibbons and Thorax and Pelvis: An Osteopathic Perspective. 2nd

ed. Edinburgh, UK: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone;

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at University of Massachusetts on November 10, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

2013. doi:10.2519/jospt.2013.4408) had Tehan1 have been replaced by referenc- 2006.

a reference erroneously omitted,3 and the ing Maitland et al.4 These changes are 2. Goodman CC, Snyder TEK. Differential Diagnosis

information pertaining to uterine fibroid reflected in the electronic version of the in Physical Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B.

embolization on pages 51 and 52 was article available at www.jospt.org (http:// Saunders Company; 2000.

3. Goodwin SC, Spies JB. Uterine fibroid emboliza-

incorrectly attributed to Goodman and dx.doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2013.4408).

We apologize for these errors. !

tion. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:690-697. http://

Snyder.2 The following reference has been dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMct0806942

added to the reference list: Goodwin SC, 4. Maitland G, Hengeveld E, Banks K, English K.

Spies JB. Uterine fibroid embolization. N Maitland’s Vertebral Manipulation. 6th ed. Waltham,

MA: Elsevier/Butterworth-Heinemann; 2001.

Engl J Med. 2009;361:690-697 (replacing

Copyright © 2013 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

EARN CEUs With JOSPT’s Read for Credit Program

JOSPT’s Read for Credit (RFC) program invites Journal readers to study and

analyze selected JOSPT articles and successfully complete online quizzes

about them for continuing education credit. To participate in the

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

program:

1. Go to www.jospt.org and click on “Read for Credit” in the left-hand

navigation column that runs throughout the site or on the link in the

“Read for Credit” box in the right-hand column of the home page.

2. Choose an article to study and when ready, click “Take Exam” for

that article.

3. Log in and pay for the quiz by credit card.

4. Take the quiz.

5. Evaluate the RFC experience and receive a personalized certificate of

continuing education credits.

The RFC program offers you 2 opportunities to pass the quiz. You may

review all of your answers—including the questions you missed. You

receive 0.2 CEUs, or 2 contact hours, for each quiz passed. The Journal

website maintains a history of the quizzes you have taken and the credits

and certificates you have been awarded in the “My CEUs” section of your

“My JOSPT” account.

196 | march 2013 | volume 43 | number 3 | journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy

43-03 rr .indd 19 2/20/2013 3:2 :50 M

You might also like

- Lumbar Spine AssesmentDocument8 pagesLumbar Spine AssesmentPavithra SivanathanNo ratings yet

- Kent's 12 ObservationsDocument4 pagesKent's 12 ObservationsRajesh Rajendran100% (4)

- Activating A Stroke Alert - A Neurological Emergency - CE591Document7 pagesActivating A Stroke Alert - A Neurological Emergency - CE591Czar Julius Malasaga100% (1)

- Respiratory Care Pocket Card English v2021.4 Pi58nnDocument2 pagesRespiratory Care Pocket Card English v2021.4 Pi58nnAdina BatajuNo ratings yet

- Centrally Mediated Abdominal Pain SyndromesDocument4 pagesCentrally Mediated Abdominal Pain SyndromesPolo Good BoyNo ratings yet

- Autonomic Dyserflexia PDFDocument16 pagesAutonomic Dyserflexia PDFAvani PatelNo ratings yet

- Hiatal Hernia FinalDocument7 pagesHiatal Hernia FinalbabiNo ratings yet

- Risk For Acute Pain Related To Surgical IncisionDocument4 pagesRisk For Acute Pain Related To Surgical IncisionMia Grace Garcia100% (1)

- RA 10606-PhilHealth LawDocument10 pagesRA 10606-PhilHealth Lawleeashlee0% (1)

- What Is This Professor Freud Like - KoellreuterDocument140 pagesWhat Is This Professor Freud Like - KoellreuterJose MuñozNo ratings yet

- NCP - Drug Study - Peptic UlcerDocument18 pagesNCP - Drug Study - Peptic UlcerEmi EspinoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To PharmacologyDocument2 pagesIntroduction To PharmacologyJoy Ann Akia PasigonNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan Age: 60 Years OldDocument4 pagesNursing Care Plan Age: 60 Years OldLouise GudmalinNo ratings yet

- Laporan Kasus VI Bahasa InggrisDocument10 pagesLaporan Kasus VI Bahasa InggrisWahyu SholekhuddinNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Pain in Physical Therapy Practice PDFDocument12 pagesAbdominal Pain in Physical Therapy Practice PDFdanielNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Visceral Pain: Clinical AspectDocument4 pagesAbdominal Visceral Pain: Clinical AspectMagdy GabrNo ratings yet

- An Approach To The Patient With Chronic Undiagnosed Abdominal PainDocument7 pagesAn Approach To The Patient With Chronic Undiagnosed Abdominal PainCarlos Arturo Caparo ChallcoNo ratings yet

- Development of A Standardized, Reproducible Screening Examination For Assessment of Pelvic Floor Myofascial PainDocument9 pagesDevelopment of A Standardized, Reproducible Screening Examination For Assessment of Pelvic Floor Myofascial PainJavi Belén Soto MoralesNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Pain in AdlutDocument5 pagesAbdominal Pain in AdlutNandaNo ratings yet

- Chest Pain: Brett E. Fenster, - Teofilo L. Lee-Chiong, JR., - G.F. Gebhart, - Richard A. MatthayDocument15 pagesChest Pain: Brett E. Fenster, - Teofilo L. Lee-Chiong, JR., - G.F. Gebhart, - Richard A. MatthayAsdffdsaNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Sensory Perception in Patients With Esophageal Chest PainDocument8 pagesAbnormal Sensory Perception in Patients With Esophageal Chest Painwijaya ajaaNo ratings yet

- Dry Needling X Dor Abdominal Incerta 2018Document5 pagesDry Needling X Dor Abdominal Incerta 2018Sarah Coelho HoraNo ratings yet

- Assessment Diagnosis Analysis Planning Intervention Rationale EvaluationDocument2 pagesAssessment Diagnosis Analysis Planning Intervention Rationale Evaluationy3nkieNo ratings yet

- Abdominal PainDocument12 pagesAbdominal PainbugraaceNo ratings yet

- The Expanding Role of Primary Care in Cancer ControlDocument5 pagesThe Expanding Role of Primary Care in Cancer ControlM.Valent DiansyahNo ratings yet

- Blue and White Illustrated Medical Healthcare in The 21st Century Education PresentationDocument32 pagesBlue and White Illustrated Medical Healthcare in The 21st Century Education PresentationMaria Victoria A. PraxidesNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Musculoskeletal Discomfort In.8Document9 pagesRisk Factors For Musculoskeletal Discomfort In.8Ariel Anaya GalvisNo ratings yet

- Saint Paul University Dumaguete College of Nursing Nursing Care Plan FormDocument10 pagesSaint Paul University Dumaguete College of Nursing Nursing Care Plan FormMary Rose Silva GargarNo ratings yet

- NCP Pain1Document4 pagesNCP Pain1java_biscocho12290% (1)

- Effect of Effleurage Techniques To Inten 82ec4d7d PDFDocument7 pagesEffect of Effleurage Techniques To Inten 82ec4d7d PDFeka istiyaniNo ratings yet

- Pacheco Carroza2021Document9 pagesPacheco Carroza2021NandaNo ratings yet

- Dolak 2011 Hip Strengthening Prior To FunctionDocument11 pagesDolak 2011 Hip Strengthening Prior To FunctionSebastian RojasNo ratings yet

- 2020 Diagnostic Criteria For Fibromyalgia - Critical Review and Future PerspectivesDocument16 pages2020 Diagnostic Criteria For Fibromyalgia - Critical Review and Future PerspectivesJulian Caro MorenoNo ratings yet

- 907 FullDocument6 pages907 FullItai IzhakNo ratings yet

- Research Paper:: Effect of Core Stability Exercises On Primary Dysmenorrhea: A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument10 pagesResearch Paper:: Effect of Core Stability Exercises On Primary Dysmenorrhea: A Randomized Controlled TrialHana HikariNo ratings yet

- Article: ResearchDocument12 pagesArticle: ResearchariniNo ratings yet

- Pelvic Osteomyelitis Presenting As Groin and Medial Thigh Pain: A Resident's Case ProblemDocument10 pagesPelvic Osteomyelitis Presenting As Groin and Medial Thigh Pain: A Resident's Case ProblemFebryLasantiNo ratings yet

- ARTICLEDocument8 pagesARTICLEazza atyaNo ratings yet

- Dietary Therapy: A New Strategy For Management of Chronic Pelvic PainDocument8 pagesDietary Therapy: A New Strategy For Management of Chronic Pelvic PainJoyce Beatriz NutricionistaNo ratings yet

- Moura 2021Document10 pagesMoura 2021Phoenix WhiteNo ratings yet

- 03章(90 146)物理治疗转诊筛查Document57 pages03章(90 146)物理治疗转诊筛查zhangpengNo ratings yet

- 907 FullDocument6 pages907 FullMilton Ricardo de Medeiros FernandesNo ratings yet

- The Significance of Esophageal Myotomy in Surgical Treatment of Diffuse Esophageal SpasmDocument6 pagesThe Significance of Esophageal Myotomy in Surgical Treatment of Diffuse Esophageal SpasmSabrina JonesNo ratings yet

- Effect of Audio and Visual Distraction On Patients Undergoing Colonscopy RCTDocument4 pagesEffect of Audio and Visual Distraction On Patients Undergoing Colonscopy RCTimkaikin001No ratings yet

- Know Pain, Know Gain? A Perspective On Pain Neuroscience Education in Physical TherapyDocument4 pagesKnow Pain, Know Gain? A Perspective On Pain Neuroscience Education in Physical TherapySamuelNo ratings yet

- Effects of Taping On Pain and Function in Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome - A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument11 pagesEffects of Taping On Pain and Function in Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome - A Randomized Controlled Trialsaeed seedNo ratings yet

- Osce ReviewerDocument119 pagesOsce Reviewerchiaruuh tNo ratings yet

- Know Pain, Know GainDocument4 pagesKnow Pain, Know GainCarlos Millan PerezNo ratings yet

- Jsafog 2013 05 147Document7 pagesJsafog 2013 05 147Anna JuniedNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Accuracy of The Slump Test For Identifying Neuropathic Pain in The Lower LimbDocument13 pagesDiagnostic Accuracy of The Slump Test For Identifying Neuropathic Pain in The Lower LimbfilipecorsairNo ratings yet

- Dolor Pelvico Cronico ACOGDocument12 pagesDolor Pelvico Cronico ACOGFELIPE MEDINANo ratings yet

- Хэвлийн архаг өвдөлт Chronic Abdominal PAIN: Todzaya.JDocument22 pagesХэвлийн архаг өвдөлт Chronic Abdominal PAIN: Todzaya.JTodzaya JargalsaikhanNo ratings yet

- Fisiologia Da Dor Visceral - 230213 - 194814Document26 pagesFisiologia Da Dor Visceral - 230213 - 194814SchitiniNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Management For Patient With Renal ProblemsDocument32 pagesNursing Care Management For Patient With Renal ProblemsMaria Victoria A. PraxidesNo ratings yet

- Musculoskeletal Pain and Exercise-Challenging Existing Paradigms and Introducing NewDocument6 pagesMusculoskeletal Pain and Exercise-Challenging Existing Paradigms and Introducing NewCelia CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Chronic Pelvic PainDocument4 pagesChronic Pelvic PainManuelNo ratings yet

- Abdominopelvic Pain Syndromes - CeaDocument6 pagesAbdominopelvic Pain Syndromes - CeaLucas CabreraNo ratings yet

- 143 283 1 SM PDFDocument5 pages143 283 1 SM PDFMasiya SiyaNo ratings yet

- Ajpgi 00173 2022Document9 pagesAjpgi 00173 2022Andi Kumalasari MappaNo ratings yet

- Humans Stomach Graphic PowerPoint Templates WidescreenDocument22 pagesHumans Stomach Graphic PowerPoint Templates WidescreenkasmaNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Pain - Pathophysiology, Classification and CausesDocument8 pagesAbdominal Pain - Pathophysiology, Classification and CausesdanukamajayaNo ratings yet

- KT Trial Added JOSPT2016Document8 pagesKT Trial Added JOSPT2016Ju ChangNo ratings yet

- Foot Massagw 5Document8 pagesFoot Massagw 5Surya Puji KusumaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Benson Relaxation On The Intensity of Spinal Anesthesia-Induced Pain After Elective General and Urologic SurgeryDocument9 pagesEffect of Benson Relaxation On The Intensity of Spinal Anesthesia-Induced Pain After Elective General and Urologic Surgeryeny_sumaini65No ratings yet

- 192 2017 Article 3536Document8 pages192 2017 Article 3536IthaNo ratings yet

- Physiotherapy For Pelvic Pain and Female Sexual Dysfunction: An Untapped ResourceDocument8 pagesPhysiotherapy For Pelvic Pain and Female Sexual Dysfunction: An Untapped ResourceLauris TrujilloNo ratings yet

- Fast Facts: Perioperative Pain: Effective management has numerous benefitsFrom EverandFast Facts: Perioperative Pain: Effective management has numerous benefitsNo ratings yet

- Gastric Bypass (GBP) and Sleeve Gastrectomy TR400.GBSG - Si: Da Vinci Si™ SystemDocument2 pagesGastric Bypass (GBP) and Sleeve Gastrectomy TR400.GBSG - Si: Da Vinci Si™ SystemShayne JacobsonNo ratings yet

- Carrier Guidance & CounsellingDocument6 pagesCarrier Guidance & CounsellingMithileshNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae Sigit Riyarto, MD, MPH: Date/place of Birth AddressDocument3 pagesCurriculum Vitae Sigit Riyarto, MD, MPH: Date/place of Birth AddressNikolas Dwi SusantoNo ratings yet