Professional Documents

Culture Documents

In The High Court at Calcutta: W.P. No.28276 (W) of 2014

Uploaded by

userfriendly3390 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views11 pagesvital order

Original Title

WP_28276W_2014_10022016_J_238

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentvital order

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views11 pagesIn The High Court at Calcutta: W.P. No.28276 (W) of 2014

Uploaded by

userfriendly339vital order

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 11

IN THE HIGH COURT AT CALCUTTA

Constitutional Writ Jurisdiction

APPELLATE SIDE

Present:

The Hon’ble Justice Tapabrata Chakraborty

W.P. No.28276 (W) of 2014

Dr. S.E.H. Imam Azam

versus

Maulana Azad National Urdu University & Ors.

For the Petitioner : Mr. Soumya Majumder,

Md. Taloy Masood Siddiqui,

Md. S. S. Siddique.

For the Respondent

Nos.2 & 6 : Mr. S. P. Mukherjee,

Mr. Debanjan Mukherjee,

Ms. Debabeena Mukherjee.

Judgment On : 10th February, 2016.

Tapabrata Chakraborty, J.

The instant writ application has been preferred challenging,

inter alia, the entire disciplinary proceeding initiated against the

petitioner and the final order passed in the same on 18th

September, 2014.

Records reveal that the writ application was initially heard

on 26th September, 2014 and an interim order was passed and

the same was extended until further orders by a subsequent

order dated 10th November, 2014 and the Court also issued

direction for exchange of affidavits. Pursuant thereto affidavits

have been exchanged by the parties.

Mr. Majumder, learned advocate appearing for the petitioner

submits that the charges framed against the petitioner are

absolutely vague and that in the enquiry proceeding the

petitioner was not granted appropriate opportunity of hearing

and the enquiry report dated 30th October, 2013 was also not

served upon the petitioner and the entire proceedings suffers

from the vice of non-compliance of the principles of natural

justice. Out of the four charges alleged against the petitioner,

three charges were found to have been proved in the enquiry and

on the basis of the same the petitioner was imposed a

punishment of stoppage of five increments with cumulative effect

and non-consideration for any promotion for the next 5 years and

non-conferment of any important/independent charge.

Furthermore, the petitioner was also transferred to Directorate of

Distance Education, MANUU Headquarters, as would be explicit

from the impugned order of punishment dated 18th September,

2014.

According to him, the punishment of withholding of

increments and promotion are disproportionate and that the

petitioner has also been directed to be transferred on the basis of

the impugned order dated 18th September, 2014 though there is

no such punishment of transfer prescribed under the Central

Civil Services (Classification, Control and Appeal) Rules, 1965

(hereinafter referred to as the said Rules of 1965) and that as

such the said order of transfer imposed against the petitioner is a

nullity.

He further submits that the petitioner is not an officer of the

said University and that as such question of application of clause

10 of the guidelines framed under the Maulana Azad National

Urdu University Act, 1996 (hereinafter referred to as the said Act

of 1996) does not apply to the petitioner since he is an employee

and not an officer. In support of such contention he has drawn

the attention of this Court to Section 9 of the said Act of 1996.

He further argues that the provisions of the said Rules of

1965 have not been appropriately followed by the respondents

and the enquiry has been conducted in a slip shod manner. On

20th August, 2013, 29th August, 2013 and 2nd October, 2013 the

enquiry was conducted in his absence and he was also not served

the enquiry report and such infirmities in the decision making

process and blatant violation of the principles of natural justice

warrants interference of this Court. In support of such

contention, Mr. Majumder has placed reliance upon the following

judgments :

(a) Sur Enamel and Stamping Works Ltd. –vs- The

Workmen, reported in AIR 1963 SC 1914 in support of

the proposition to the effect that a domestic inquiry

should be held in strict consonance with the principles of

the natural justice;

(b) Union Of India –vs- H.C.Goel, reported in AIR 1964

SC 364 in support of the proposition to the effect that the

enquiry officer is not required to make any

recommendation as to the punishment which may be

imposed on the delinquent;

(c) Managing Director, ECIL, Hyderabad –vs-

B.Karunakar, reported in AIR 1994 SC 1074 in

support of the proposition to the effect that even if the

statutory rules are silent the employee has a right to

receive a copy of the Inquiry Report;

(d) Union of India & Others –vs- Prakash Kumar Tandon,

reported in 2009 (2) SCC 541 in support of the

proposition to the effect that the enquiry officer must

perform his function reasonably and that the proceeding

must be fairly conducted;

(e) Union of India & Others –vs- S.K. Kapoor, reported in

2011 (4) SCC 589 in support of the proposition to the

effect that any material which is relied upon in

departmental proceedings must be supplied to the

charge-sheeted employee in advance so that he may have

a chance to rebut the same.

Per Contra, Mr. Mukherjee, learned advocate appearing for

the respondent nos.2 and 6 submits that the charges under

Articles I and II pertaining to failure on the part of the petitioner

in selecting and recommending the study centre at Saharsa (SL.

No.168) which had no infrastructure for conducting examination

for about 300 candidates and the charge under Article IV

pertaining to failure of the petitioner in selecting and

recommending the study centre at Sara Mohanpur (SC. No.163)

were admitted by the petitioner in course of enquiry as would be

explicit from the minutes of the hearing conducted on 27th

October, 2013. The petitioner admitted that the study centre at

Saharsa (SL. No.168) was recommended by him in good faith

without any inspection in person and that accordingly there had

been a mistake on his part in recommending for activation of the

said study centre. He categorically stated that as there was no

instruction from the Headquarters to inspect, he neither made

any inspection nor sent any person to ascertain whether the said

study centre was functioning or not as per the norms of the

University or was having sufficient infrastructure for conducting

the examination. He also admitted his failure to write to the

University as regards any need to inspect the said study centre.

As regards the charge under Article IV the petitioner categorically

stated that the study centre at Sara Mohanpur, Darbhanga (SC.

No.163) was recommended by him without making any

inspection and in spite of knowing the fact that close by the same

a study centre of the said University was functioning at a place

about 15 Kms. away. The statements made by the petitioner and

as recorded in course of hearing have been duly signed by him

and his signature appears at every page of the said minutes.

According to Mr. Mukherjee, the admission on the part of

the delinquent is the best evidence and in the backdrop of such

admission appropriate punishments have been imposed upon the

petitioner and that as such the allegation that the punishments

as imposed are disproportionate to the charges, is absolutely

unfounded.

He further contends that having admitted the charges the

petitioner cannot challenge the punishments imposed, on a

purported plea that the enquiry report was not served upon him.

Drawing the attention of this Court to the enquiry report dated

30th October, 2013, he submits that in the backdrop of the

admissions made by the petitioner, the enquiry officer recorded

his recommendations. Even assuming but not admitting that the

said report has not been served upon the petitioner, the same

does not cause any prejudice.

As regards the allegation to the effect that the transfer was

imposed as a punishment pursuant to the disciplinary

proceeding, Mr Mukherjee submits that the order of transfer is

not punitive and is not an order pertaining to the disciplinary

proceeding and the same has been issued only in the interest of

administration and that the same is relatable to the order to the

effect that no important/independent charge should be given to

him. The judgments as relied upon by the petitioner are

distinguishable on facts.

Drawing the attention of this Court to the provisions of the

said Act of 1996 and the guidelines framed there under, Mr.

Mukherjee submits that the said provisions are clearly applicable

to the petitioner. Furthermore, it would also be explicit from the

service contract dated 4th July, 2005 that the petitioner is of the

teacher’s / officer’s rank and his status shall be that of Regional

Director.

In reply, Mr. Majumder disputes the contention of Mr.

Mukherjee and submits that for the lack of proper directives from

the headquarters of the said University, the petitioner cannot be

made to suffer and the said issue though raised in course of the

enquiry was not considered and the petitioner has been

victimised.

I have heard the learned advocates appearing for the

respective parties and I have considered the materials on record.

The undisputed facts are that the petitioner was issued a

charge sheet dated 1st October, 2012 proposing to hold an

inquiry under Rule 14 of the said Rules of 1965 and in annexure

‘2’ of the said charge sheet, the enquiry report dated 10th May,

2012 was enclosed and upon consideration of the same the

petitioner submitted a reply on 18th October, 2012. Thereafter an

Enquiry Officer was appointed and the petitioner was asked to

appear in the said enquiry and the petitioner duly participated in

the same and the statements made by the petitioner in course of

such enquiry on 27th October, 2013 were duly recorded and duly

signed by the petitioner on the self-same date. The documents

pertaining to such enquiry were thereafter placed before the

Executive Council and by a resolution dated 12th February, 2014

the Pro Vice-Chancellor was asked to furnish his

recommendations and upon consideration of the same the

Executive Council imposed the punishment.

I do not find any substance in the argument of Mr.

Majumder to the effect that the charges levelled against the

petitioner are absolutely vague. A perusal of the charge sheet

does not reveal any ambiguity or vagueness in the charges. The

charges are categoric and the same do not, by the furthest of

imagination, express that the disciplinary authority had a

mindset to penalise the petitioner.

The guidelines framed under the said Act of 1996 read with

the service contract as executed by the petitioner clearly reveal

that the same are applicable to the petitioner and clause 10 of

the said guidelines casts an obligation upon the officers of the

regional centres to carry out periodic inspection of the study

centres and to ensure that they are being run as per the norms.

It would be an absurdity to suggest that being the Director in a

Regional Centre the petitioner is not required to discharge such

statutory obligation. As a Regional Director it is also otherwise

incumbent upon him to keep a vigil over the study centres.

The fact of alleged non-service of the enquiry report has not

been appropriately pleaded in the writ application save and

except an averment in paragraph 28 of the writ application

wherein the date of the enquiry report has also not been

mentioned. The statements made in paragraph 28 of the writ

application were categorically denied by the respondents through

the averments made in paragraph 16 of the affidavit-in-

opposition. Such denial has also not been dealt with by the

petitioner in paragraph 16 of the reply. The minutes of the

enquiry proceedings further reveal that on 20th August, 2013 the

petitioner’s reply to the charges was considered and certain

questions were set to be put to him in course of the enquiry. On

29th August, 2013 further questions were framed on the basis of

the records and guidelines and on 2nd October, 2013 it was

decided that opportunity would be granted to the petitioner to

produce evidence. Thus, on the said three dates no final decision

was arrived at and the contents of the said minutes do not reveal

any prejudice caused to the petitioner. The procedural provisions

are generally meant for affording a reasonable and adequate

opportunity to the delinquent and they are conceived in his

interest and violation of any such procedural provisions cannot

be said to have automatically vitiated the enquiry. The principle

of natural justice needs to be examined on the basic principle of

“prejudice caused”.

The authority of the Writ Court to interfere with the

disciplinary action is limited and the Writ Court cannot, in

exercise of power of judicial review, reappreciate the evidence and

that the Writ Court cannot sit in appeal over the orders passed

by the Disciplinary Authority. The expression ‘sufficiency of

evidence’ postulates existence of some evidence which links the

charged officer with the misconduct alleged against him and in

the instant case the petitioner himself has admitted the charges.

It is also a settled proposition of law that admission is the

best evidence unless the party who has admitted it proves it to

have been admitted under a wrong presumption. An admission

is the best evidence that an opposing party can rely upon and it

is decisive of the matter, unless successfully withdrawn or proved

erroneous. Records do not reveal that the admissions made by

the petitioner in course of the enquiry proceeding were extracted

by any force or fear. The admissions are also not contradictory in

nature and the same has neither been withdrawn by the

petitioner nor the same has been proved to be erroneous.

There is no dispute as regards the proposition of law as laid

down in the judgments relied upon by the petitioner. In the

departmental proceedings dealt with in the said judgments there

is no admission on the part of the employee and thus the entire

factual scenario is different in the instant case and accordingly

the said judgments have no manner of application.

It is well-settled that any interference with the order of

punishment is permissible in very rare cases. In the instant case

the punishment is not so disproportionate to the established

charges that it would appear unconscionable and actuated with

malice. The petitioner’s conduct was reproachable and his

understanding of responsibility and adherence to discipline was

questionable as would be explicit from his admissions made in

course of the enquiry proceeding.

However, the argument of Mr. Majumder to the effect that

the order of transfer incorporated in the final order of

punishment in the disciplinary proceeding is absolutely perverse

and without jurisdiction, carries weight. The order of transfer

cannot be imposed as a punishment upon the petitioner in the

disciplinary proceeding since no such punishment is provided for

under Rule 11 of the said Rules 1965. It is a settled proposition

of law that punishment not prescribed under the rules, as a

result of disciplinary proceedings, cannot be awarded. Holding

departmental proceedings and recording of a finding of guilt

against any delinquent and imposing the punishment for the

same is a quasi-judicial function and not an administrative one.

Imposing the punishment for a proved delinquency is regulated

and controlled by the statutory rules. Therefore, while performing

the quasi-judicial functions, the authority is not permitted to

ignore the statutory rules under which punishment is to be

imposed. The disciplinary authority is bound to proceed in strict

adherence to the said Rules. Thus, the order of transfer as a

measure of penalty being outside the purview of the statutory

rules is a nullity and cannot be enforced against the petitioner.

For the reasons discussed above, save and except the order

of transfer, other punishments as imposed by the order dated

18th September, 2014 are not interfered with. The order of

transfer as imposed upon the petitioner by the memorandum

dated 18th September, 2014 is set aside and quashed.

The writ application is, thus, partly allowed.

There shall, however, be no order as to costs.

Urgent Photostat certified copy of this judgment, if applied

for, be given to the parties, as expeditiously as possible, upon

compliance with the necessary formalities in this regard.

(Tapabrata Chakraborty, J.)

You might also like

- Maibam Ibohal Singh Vs State of Manipur and Ors 02GH200904062119070665COM443482Document6 pagesMaibam Ibohal Singh Vs State of Manipur and Ors 02GH200904062119070665COM443482Yug SinghNo ratings yet

- WP 6309 2006 FinalOrder 14-Sep-2022Document24 pagesWP 6309 2006 FinalOrder 14-Sep-2022Sakshi ShettyNo ratings yet

- Salam Kesho Singh Vs State of Manipur and Ors 21040100629COM824654Document3 pagesSalam Kesho Singh Vs State of Manipur and Ors 21040100629COM824654Yug SinghNo ratings yet

- O.A 1136.16, Termination Challenged, DB. 10.22Document9 pagesO.A 1136.16, Termination Challenged, DB. 10.22Sunil Vijay ShelarNo ratings yet

- 2013LHC698Document4 pages2013LHC698Mudasar SahmalNo ratings yet

- LP Misra Vs State of UP 26081998 SC0506s980261COM327290Document4 pagesLP Misra Vs State of UP 26081998 SC0506s980261COM327290Michael DissuosiaNo ratings yet

- In The Lahore High Court, Lahore: Judgment SheetDocument47 pagesIn The Lahore High Court, Lahore: Judgment SheetAsim ShahzadNo ratings yet

- A Anji Kumar Vs The Chairman Tamil Nadu Uniformed TN2018100818162134215COM695314Document11 pagesA Anji Kumar Vs The Chairman Tamil Nadu Uniformed TN2018100818162134215COM695314Stark SpeaksNo ratings yet

- 2020 Ballb 100Document15 pages2020 Ballb 100Shriyadita SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Reserve Bank of India and Ors Vs The Presiding OffDE20151103152310458COM393000Document7 pagesReserve Bank of India and Ors Vs The Presiding OffDE20151103152310458COM393000PVR 2020to21 FilesNo ratings yet

- Reserve Bank of India and Ors Vs The Presiding OffDE20151103152310458COM393000Document7 pagesReserve Bank of India and Ors Vs The Presiding OffDE20151103152310458COM393000PVR 2020to21 FilesNo ratings yet

- 2021 Tzca 3528Document18 pages2021 Tzca 3528Nuru MzenhaNo ratings yet

- Dr. Sambuddha Chakrabarti and Hiranmay Bhattacharyya, JJDocument7 pagesDr. Sambuddha Chakrabarti and Hiranmay Bhattacharyya, JJsid tiwariNo ratings yet

- Internship Diary: 18 JULY, 2023 TO 18 AUGUST, 2023Document20 pagesInternship Diary: 18 JULY, 2023 TO 18 AUGUST, 2023sssNo ratings yet

- Zahira Habibullah Sheikh and Ors Vs State of Gujars040490COM369164Document8 pagesZahira Habibullah Sheikh and Ors Vs State of Gujars040490COM369164Ashhab KhanNo ratings yet

- J.B. Pardiwala, J.: Equiv Alent Citation: (2016) 1GLR139Document25 pagesJ.B. Pardiwala, J.: Equiv Alent Citation: (2016) 1GLR139themis sikkimNo ratings yet

- Wa0042.Document16 pagesWa0042.Tatini ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- 2014-Binod Kumar & Ors Vs State of BiharDocument9 pages2014-Binod Kumar & Ors Vs State of BiharPRASHANT SAURABHNo ratings yet

- CPC Project 1Document16 pagesCPC Project 1Rajat choudharyNo ratings yet

- Code OF Criminal Procedure 1973: CASE LAW: A.G. V. Shiv Kumar Yadav and AnrDocument12 pagesCode OF Criminal Procedure 1973: CASE LAW: A.G. V. Shiv Kumar Yadav and Anrakshit sharmaNo ratings yet

- Jyoti Prakash Vs Internal Appellate Committee and OR2018220618155808169COM272664 PDFDocument12 pagesJyoti Prakash Vs Internal Appellate Committee and OR2018220618155808169COM272664 PDFRATHLOGICNo ratings yet

- Discharge Application Rejected Cases: Allahabad High CourtDocument56 pagesDischarge Application Rejected Cases: Allahabad High CourtParinita SinghNo ratings yet

- WP4252 97 (04.07.19)Document9 pagesWP4252 97 (04.07.19)Rupali JainNo ratings yet

- JHC 200300004772019 2 WebDocument16 pagesJHC 200300004772019 2 WebJatinder SinghNo ratings yet

- In The High Court of Orissa at Cuttack W.P. (C) No.12250 of 2022Document8 pagesIn The High Court of Orissa at Cuttack W.P. (C) No.12250 of 2022Manish KumarNo ratings yet

- CRPC Case LawDocument7 pagesCRPC Case LawCROSS TREDERSNo ratings yet

- In The Supreme Court of Pakistan: PresentDocument16 pagesIn The Supreme Court of Pakistan: PresentTariq HussainNo ratings yet

- Ruling Sarah Nabawanuka & Others Vs Makerere University & 2 OthersDocument10 pagesRuling Sarah Nabawanuka & Others Vs Makerere University & 2 Otherssamurai.stewart.hamiltonNo ratings yet

- Nishith - Chandra - Tiwari - Vs - Uttar - Pradesh - Sahkari - Gru030843COM671037Document3 pagesNishith - Chandra - Tiwari - Vs - Uttar - Pradesh - Sahkari - Gru030843COM671037Kanishka SihareNo ratings yet

- Crl.p. 328 2023Document3 pagesCrl.p. 328 2023nawaz606No ratings yet

- Phaguni Nilesh Lal v. Registrar General, Supreme CourtDocument56 pagesPhaguni Nilesh Lal v. Registrar General, Supreme CourtBar & Bench0% (1)

- In The Court of Shri Paramjeet Singh, Judge, Special Court, Chandigarh. (UID NO. PB0035)Document12 pagesIn The Court of Shri Paramjeet Singh, Judge, Special Court, Chandigarh. (UID NO. PB0035)NaitikNo ratings yet

- Organising ApprovalDocument13 pagesOrganising ApprovalSYEDA MYSHA ALINo ratings yet

- Suman Verma Vs Union of IndiaDocument6 pagesSuman Verma Vs Union of IndiaJackieNo ratings yet

- Swami Chinmiyanand Saraswati Pupil Vs State of Up and Another Allahabad High Court 450392Document54 pagesSwami Chinmiyanand Saraswati Pupil Vs State of Up and Another Allahabad High Court 450392samNo ratings yet

- LoadingDocument3 pagesLoadingjai_gds7942No ratings yet

- Altamas Kabir, C.J.I., Anil R. Dave and Vikramajit Sen, JJDocument4 pagesAltamas Kabir, C.J.I., Anil R. Dave and Vikramajit Sen, JJANUJ SINGH SIROHINo ratings yet

- In The Gauhati High Court (The High Court of Assam, Nagaland, Mizoram and Arunachal Pradesh) Crl. Pet. No. 250/2013Document13 pagesIn The Gauhati High Court (The High Court of Assam, Nagaland, Mizoram and Arunachal Pradesh) Crl. Pet. No. 250/2013Syed Imran AdvNo ratings yet

- Nadeem AsgharDocument23 pagesNadeem Asgharazan janjuaNo ratings yet

- Part IDocument21 pagesPart IVAISHNAVI P SNo ratings yet

- Tinlianthang Vaiphei, J.: Equivalent Citation: 2015 (3) GLT346Document13 pagesTinlianthang Vaiphei, J.: Equivalent Citation: 2015 (3) GLT346sumeet_jayNo ratings yet

- CasesDocument14 pagesCasesofficialchannel8tNo ratings yet

- Ram Bahadur YadavDocument4 pagesRam Bahadur YadavKARTHIKEYAN MNo ratings yet

- MCRC 18115 2019 FinalOrder 03-May-2019Document4 pagesMCRC 18115 2019 FinalOrder 03-May-2019AdityaSharmaNo ratings yet

- Ayaaubkhan Noorkhan Pathan Vs State of Maharashtra Ors On 8 November 2012Document16 pagesAyaaubkhan Noorkhan Pathan Vs State of Maharashtra Ors On 8 November 2012anwa1No ratings yet

- SCI 498AQuashedDocument7 pagesSCI 498AQuashedshaktijhalaNo ratings yet

- Nujs OrderDocument6 pagesNujs OrderlegallyindiaNo ratings yet

- Willful Disobey Ram KishanDocument10 pagesWillful Disobey Ram KishanSankanna VijaykumarNo ratings yet

- Suresh Kumar Vs State of Haryana and Others On 24 March 2022Document5 pagesSuresh Kumar Vs State of Haryana and Others On 24 March 2022Baar YoutubeNo ratings yet

- Epuru Sudhakar and Ors Vs Govt of AP and OrsDocument23 pagesEpuru Sudhakar and Ors Vs Govt of AP and OrsSakshi AnandNo ratings yet

- Bhupinder Kumar Sharma Vs Bar Association Pathankot On 31 October, 2001Document4 pagesBhupinder Kumar Sharma Vs Bar Association Pathankot On 31 October, 2001pankaj9umNo ratings yet

- Moot Court Case No - 2Document17 pagesMoot Court Case No - 2omkarwaje99No ratings yet

- Delhi High Court OrderDocument3 pagesDelhi High Court OrderRakeshGuptaNo ratings yet

- Mahendra Singh Rajawat Vs Punjab National Bank andRH2023120123172611362COM716539Document6 pagesMahendra Singh Rajawat Vs Punjab National Bank andRH2023120123172611362COM716539deepaNo ratings yet

- Locus Standi of Third Party To Question Caste Certificate - Appellant Fined 2012 SCDocument37 pagesLocus Standi of Third Party To Question Caste Certificate - Appellant Fined 2012 SCSridhara babu. N - ಶ್ರೀಧರ ಬಾಬು. ಎನ್No ratings yet

- Remand Back of Case Under Section 391 in AppealDocument47 pagesRemand Back of Case Under Section 391 in AppealSudeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- Drafting Applications Under CPC and CrPC: An Essential Guide for Young Lawyers and Law StudentsFrom EverandDrafting Applications Under CPC and CrPC: An Essential Guide for Young Lawyers and Law StudentsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- The History and Transformation of the California Workers’ Compensation System and the Impact of Senate Bill 899 and the Current Law Senate Bill 863From EverandThe History and Transformation of the California Workers’ Compensation System and the Impact of Senate Bill 899 and the Current Law Senate Bill 863No ratings yet

- Article On New Labuan LawsDocument8 pagesArticle On New Labuan LawsMadzlan HussainNo ratings yet

- (A State University Established by Act No. 9 of 2012) Navalurkuttapattu, Srirangam Taluk, Tiruchirappalli - 620 009, Tamil NaduDocument17 pages(A State University Established by Act No. 9 of 2012) Navalurkuttapattu, Srirangam Taluk, Tiruchirappalli - 620 009, Tamil NaduSonali DalaiNo ratings yet

- History of Company LegislationDocument2 pagesHistory of Company LegislationShrujan SinhaNo ratings yet

- 3A. Invitation To Bid (Staggered Delivery)Document3 pages3A. Invitation To Bid (Staggered Delivery)Bdak B. IbiasNo ratings yet

- TIA-568.0-E March 2020 Telecomm Cabling StandardDocument70 pagesTIA-568.0-E March 2020 Telecomm Cabling Standardafouda67% (3)

- Ichong V HernandezDocument6 pagesIchong V Hernandezmandy paladNo ratings yet

- © The Institute of Chartered Accountants of IndiaDocument43 pages© The Institute of Chartered Accountants of IndiachiragNo ratings yet

- Consti Reviewer NotesDocument5 pagesConsti Reviewer NotesArvhie SantosNo ratings yet

- SITXGLC001 Assessment 1 T1 2022 1 1 PDFDocument7 pagesSITXGLC001 Assessment 1 T1 2022 1 1 PDFMary Flor Agbayani KyosangshinNo ratings yet

- Brgy. OrdinancesDocument2 pagesBrgy. OrdinancesJakbean RicardeNo ratings yet

- ISO/IEC 17065:2012 Checklist Conformity Assessment - Requirements For Bodies Certifying Products, Processes and ServicesDocument56 pagesISO/IEC 17065:2012 Checklist Conformity Assessment - Requirements For Bodies Certifying Products, Processes and Servicesjessica edwardsNo ratings yet

- Ordnance Factory-AMC Renewal Offer-EVO40Document4 pagesOrdnance Factory-AMC Renewal Offer-EVO40Chetan KaleNo ratings yet

- Mandatory DisclosureDocument2 pagesMandatory DisclosureAlanRichardsonNo ratings yet

- National Highways Act 1956Document8 pagesNational Highways Act 1956Bipul PandeyNo ratings yet

- Southern Miss (2024)Document9 pagesSouthern Miss (2024)Matt BrownNo ratings yet

- Volleyball History Timeline InfographicDocument1 pageVolleyball History Timeline Infographicmangopie00000No ratings yet

- 0623CanmoreLeavetoAppeal APP (AP) 2201 0148ACDocument4 pages0623CanmoreLeavetoAppeal APP (AP) 2201 0148ACGregNo ratings yet

- Torrens System: Principle of TsDocument11 pagesTorrens System: Principle of TsSyasya FatehaNo ratings yet

- 2011civil Procedure Remedial Law General Principles IncludedDocument164 pages2011civil Procedure Remedial Law General Principles IncludedJohn BernalNo ratings yet

- Hastings 2017 Syllabus Animal Law CourseDocument4 pagesHastings 2017 Syllabus Animal Law CourseMitchNo ratings yet

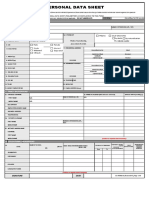

- Personal Data Sheet: Kiangan, IfugaoDocument4 pagesPersonal Data Sheet: Kiangan, IfugaoCyprene Chady DumawatNo ratings yet

- Retainer Contract Know All Men by These Presents: This CONTRACT Made and Executed by and BetweenDocument3 pagesRetainer Contract Know All Men by These Presents: This CONTRACT Made and Executed by and BetweenKwesi DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Mod17Wk15-Constitutional-LawDocument30 pagesMod17Wk15-Constitutional-LawTiara LlorenteNo ratings yet

- Tax General Principle (Cases)Document40 pagesTax General Principle (Cases)Keepy FamadorNo ratings yet

- Budgetary Quotation Summary - Sensor Update: M/D TotcoDocument8 pagesBudgetary Quotation Summary - Sensor Update: M/D Totcocmrig74No ratings yet

- Araneta v. DinglasanDocument3 pagesAraneta v. DinglasanCedrick100% (1)

- NPC v. BenguetDocument2 pagesNPC v. BenguetAlexa Valaree SalugsuganNo ratings yet

- Ichong, Etc., Et Al. vs. Hernandez, Etc., and Sarmiento 101 Phil. 1155, May 31, 1957, No. L-7995Document2 pagesIchong, Etc., Et Al. vs. Hernandez, Etc., and Sarmiento 101 Phil. 1155, May 31, 1957, No. L-7995Almer TinapayNo ratings yet

- Greco Antonious Beda B. Belgica v. Executive Secretary Paquito N. Ochoa, Jr. GR No 208566, November 19, 2013, 710 SCRA 1Document2 pagesGreco Antonious Beda B. Belgica v. Executive Secretary Paquito N. Ochoa, Jr. GR No 208566, November 19, 2013, 710 SCRA 1Jeorge VerbaNo ratings yet

- The Indian Ports Act 1908Document44 pagesThe Indian Ports Act 1908tallmansahuNo ratings yet