Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Indian Constitution Guarantees Equal Rights To All Citizens Irrespective of Their Gender

Uploaded by

Piku NaikOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Indian Constitution Guarantees Equal Rights To All Citizens Irrespective of Their Gender

Uploaded by

Piku NaikCopyright:

Available Formats

The Indian Constitution guarantees equal rights to all citizens irrespective of their gender, religion, or

caste. However, the reality is different for Muslim women in India. They have been subjected to numerous

discriminatory practices that have deprived them of their basic rights. In recent years, there have been

several landmark judgments by Indian courts that have recognized the rights of Muslim women. One such

judgment was the Shah Bano case, which led to the introduction of Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure

Code (CrPC).

Section 125 of the CrPC is a provision that provides maintenance to wives, children, and parents who are

unable to maintain themselves. It applies to all religions and is not specific to any particular religion. The

section was introduced after the Shah Bano case, where the Supreme Court held that a divorced Muslim

woman was entitled to maintenance from her former husband under Section 125 of the CrPC. This

decision was met with widespread protests from Muslim organizations, and the government of the day

responded by passing the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986.

The Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986, restricted the rights of Muslim women

and was criticized for being discriminatory. It provided that a divorced Muslim woman was entitled to

maintenance only for the period of iddat (three months after the divorce) and that the amount of

maintenance could not exceed the amount paid during the iddat period. This act was widely criticized for

being discriminatory towards Muslim women, and the Supreme Court struck it down in 2017 in the

Shayara Bano case.

Despite the existence of Section 125, Muslim women in India face several challenges in claiming their

rights. One of the biggest challenges is the lack of awareness about their rights. Many Muslim women are

not aware of the provision and do not know that they are entitled to maintenance from their husbands.

Another challenge is the social stigma attached to divorce in the Muslim community. Muslim women who

seek divorce or claim maintenance from their husbands are often ostracized by their families and

communities. This makes it difficult for them to pursue their legal rights.

The lack of support from the state and the legal system is another challenge faced by Muslim women. The

state has been slow in implementing measures to protect the rights of Muslim women, and the legal system

is often biased against them. Muslim women often face discrimination in the courts and are not given the

same rights as women belonging to other religions.

Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) is a crucial provision in Indian law that aims to

provide maintenance to dependent family members who are unable to maintain themselves. This includes

wives, children, and parents. The provision is gender-neutral and applies to both men and women, but

Muslim women's rights under this section have been a subject of significant debate and controversy.

The main issue at hand is the question of whether Muslim women can claim maintenance under Section

125 CrPC, given that Muslim personal law recognizes a different system of maintenance. While the

Muslim personal law recognizes the concept of 'mahr' or dowry, which is payable by the husband to the

wife at the time of marriage, it does not provide for the concept of maintenance in the same way that it is

understood in secular law. This has led to confusion and conflicting judgments regarding the applicability

of Section 125 CrPC to Muslim women.

Following are the landmark judgements that have dealt with the issue of Muslim women's rights

under Section 125 CrPC:

Shah Bano Case[i] (1985)

The Shah Bano case is one of the most important cases that dealt with Muslim women's rights

under Section 125 CrPC. In this case, Shah Bano, a Muslim woman, filed a petition under Section

125 CrPC claiming maintenance from her husband, who had divorced her after 43 years of

marriage. The case went all the way up to the Supreme Court, where the court held that Muslim

women are entitled to maintenance under Section 125 CrPC, irrespective of their personal law.

The court observed that the provision of maintenance under Section 125 CrPC is a secular

provision that applies to all citizens, irrespective of their religion. The court further held that if the

Muslim personal law is found to be in conflict with the provisions of the constitution, then the

constitution would prevail. The court, therefore, directed Shah Bano's husband to pay maintenance

to her.

The Shah Bano case created a lot of controversy, particularly among conservative Muslims who

believed that the Supreme Court's decision was an interference in the Muslim personal law. The

case led to the passage of the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986, which

sought to limit the scope of the Supreme Court's decision in the Shah Bano case.

Danial Latifi Case[ii] (2001)

The Danial Latifi case is another important case that dealt with Muslim women's rights under

Section 125 CrPC. In this case, the husband had divorced his wife, and the wife had filed a

petition under Section 125 CrPC claiming maintenance. The husband argued that since he had

already paid the 'mehr' to his wife at the time of marriage, he was not liable to pay any further

maintenance.

The Supreme Court, in this case, held that the concept of 'mehr' is distinct from the concept of

maintenance, and the mere payment of 'mehr' does not absolve the husband of his obligation to

maintain his wife. The court observed that while the Muslim personal law recognizes the concept

of 'mehr', it does not provide for the same comprehensive maintenance as provided under Section

125 CrPC.

The court further held that Section 125 CrPC is a beneficial provision that is intended to provide

immediate relief to the dependent family members. The court, therefore, directed the husband to

pay maintenance to his wife under Section 125 CrPC.

Legal position of Muslim Women relating to maintenance

In Islam, “Maintenance” is termed as “Nafaqah”, which literally means „an amount spent by a man over

his family. According to many Muslim legal philosophers, maintenance includes all those things which are

essential to lead a life such as food, clothing and residence.

It is believed that a woman on her marriage gives up her all other avocations and entirely devotes herself to

the welfare of the family. In particular, she shares her emotions, sentiments, mind and body with her

husband, and this investment of her in the marriage is a sacramental sacrifice which is far too enormous

and can not be measured in terms of money.

Here, let‟s have a look at how and to what extent rights of maintenance of Muslim woman has been laid

down by the legislation and the judicial precedents in India.

This was a landmark case in the Indian legal history of a 62-year-old woman, who was divorced and

therefore, moved Supreme Court for claiming maintenance from her husband as her husband was

contesting her claim on the ground that he had already given the payment of mahrdue to her under Muslim

personal law so her claim for maintenance should be dismissed.

The Hon‟ble Supreme Court while deciding this controversial issue held that, mahr is an amount which is

payable in consideration of the marriage. Therefore, no amount which is payable in consideration of the

marriage can possibly be described as an amount payable in consideration of the divorce. „Mahr‟ is paid as

a mark of respect to the wife. Therefore, a sum payable to the wife out of respect cannot be a sum payable

by the husband to the wife for her maintenance on divorce. It further stated that generally the liability of

the husband to provide maintenance to his wife is limited to the period of iddat but if she is unable to

maintain herself, she is entitled to take recourse to Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973.

The Hon‟ble Court concluded that the right conferred by Section 125 can be exercised irrespective of

personal law of the parties.

The Hon‟ble Supreme Court also held that Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 provides

maintenance rights to every woman irrespective of religion.

This case is seen as one of a milestone wherein Hon‟ble Supreme Court duly held that in case if any

conflict arises between Section 125 of the Code and the personal law, then in such a case former prevails

and thus the liability of the husband to pay maintenance to his wife extends beyond the period of iddat in

the circumstances where wife does not have sufficient means to maintain herself.

Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986

The Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986 was enacted on 19th May, 1986 to

protect the rights of a Muslim women who have been divorced by or have obtained divorce from, their

husbands.

The provisions of this Act provided that the former husband must provide “a reasonable and fair

provision” as maintenance within the period of iddat. Thereafter, if in case she is unable to maintain herself

after the period of iddat, she can claim maintenance from her relatives and in case if they cannot pay, then

she can claim from the Wakf Board.

In the case “DanialLatifi Versus Union Of India,(2001)7 SCC 740,” the constitutional validity of the

MWPRDA, 1986 was challenged as being violative of the right to equality guaranteed under Article 14 of

the Indian Constitution. Further, it deprived Muslim women of maintenance benefits equivalent to those

provided to other women under Section 125 of Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 and it was argued that this

law would leave Muslim women destitute and thus was violative of the right to life guaranteed under

Article 21 of the Indian Constitution as the same excludes Muslim women from the purview of sec 125 of

the Code.

The Hon‟ble Supreme Court after interpreting the provision of the Act upheld its constitutionality and

came to the conclusion that a Muslim husband is liable to pay reasonable amount of maintenance for the

future of his divorced wife. It means amount entitled by a wife during the iddat period should be large

enough so that she can easily maintain herself during iddat period as well as in future in order to survive

and fulfill her basic needs. Thus, a divorced muslim woman is entitled to maintenance for a lifetime until

she is married again. The court concluded that the Act does not violate Articles 14, 15 and 21 and hence, is

not ultra vires and Section 3 of the Act is only a substitution of Section 125 Crpc and held:-

“1) a Muslim husband is liable to make reasonable and fair provision for the future of the divorced wife

which obviously includes her maintenance as well. Such a reasonable and fair provision extending beyond

the iddat period must be made by the husband within the iddat period in terms of Section 3(1)(a) of the Act.

2) Liability of Muslim husband to his divorced wife arising under Section 3(1)(a) of the Act to pay

maintenance is not confined to iddat period.

3) A divorced Muslim woman who has not remarried and who is not able to maintain herself after iddat

period can proceed as provided under Section 4 of the Act against her relatives who are liable to maintain

her in proportion to the properties which they inherit on her death according to Muslim law from such

divorced woman including her children and parents. If any of the relatives being unable to pay

maintenance, the Magistrate may direct the State Wakf Board established under the Act to pay such

maintenance.

4) The provisions of the Act do not offend Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Constitution of India.”

Similar view was taken by the Hon‟ble Supreme Court in the case of “IqbalBanoversus State of UP,

Criminal Appeal No. 795 of 2001, wherein it was stated that the provisions of the Act do not contravene

Articles 14,15 and 21 of the Indian Constitution.

The apex court’s forthcoming ruling holds the potential to

bridge legal schisms and affirm the rights of marginalized

segments, reinforcing the constitutional ethos of equality and

justice for all.

You might also like

- Chapter 7Document10 pagesChapter 7STAR PRINTINGNo ratings yet

- Chapter-I: 1 Satayjeet, A. Desai, Mulla's Principles of Hindu Law, V. II (1998, 17th Ed,)Document11 pagesChapter-I: 1 Satayjeet, A. Desai, Mulla's Principles of Hindu Law, V. II (1998, 17th Ed,)Satyam MishraNo ratings yet

- Danial Latifi V UOIDocument5 pagesDanial Latifi V UOIThomas JosephNo ratings yet

- Danial Latifi V Union of India-An AnalysisDocument7 pagesDanial Latifi V Union of India-An AnalysisSushmita NathNo ratings yet

- Ucc and Judicial TrendDocument10 pagesUcc and Judicial TrendabhishekNo ratings yet

- Family Law - Ii: Assignment No.: 5Document5 pagesFamily Law - Ii: Assignment No.: 5Aman jainNo ratings yet

- Case CommentaryDocument3 pagesCase CommentaryDoll KhanNo ratings yet

- Critigal Subission 1Document11 pagesCritigal Subission 1NISHI JAINNo ratings yet

- Mohd Ahmad Khan V Shah Bano CaseDocument7 pagesMohd Ahmad Khan V Shah Bano CaseVishal Ravisankar100% (1)

- Quantum of MaintenanceDocument4 pagesQuantum of MaintenanceHarshita SarinNo ratings yet

- Case Summary (Family Law Assignment)Document8 pagesCase Summary (Family Law Assignment)anushka kashyapNo ratings yet

- Mohd. Ahmed Khan Vs Shah Banu BegumDocument7 pagesMohd. Ahmed Khan Vs Shah Banu BegumNitin SuryawanshiNo ratings yet

- Case Study - Section 125. Shah Bano CaseDocument5 pagesCase Study - Section 125. Shah Bano CaseAshwanth M.SNo ratings yet

- Danial Latifi Vs Union of IndiaDocument13 pagesDanial Latifi Vs Union of Indiaaangi sanghviNo ratings yet

- Danial Latifi Vs Union of IndiaDocument6 pagesDanial Latifi Vs Union of IndiaArjun PaigwarNo ratings yet

- Women and Law ProjectDocument9 pagesWomen and Law ProjectDaniyal SirajNo ratings yet

- Danial Latifi V. Union of India: Arvind Singh KushwahaDocument5 pagesDanial Latifi V. Union of India: Arvind Singh KushwahaghjegjwNo ratings yet

- DocumentDocument5 pagesDocumentTushar KaliaNo ratings yet

- Muslim Wife and MaintenanceDocument5 pagesMuslim Wife and MaintenanceHARSH KUMARNo ratings yet

- Ba0200032 Family Law IDocument10 pagesBa0200032 Family Law Inivedidha arulselvamNo ratings yet

- Shah Bano Case and Its Impact On Muslim Divorce Laws: Author: Associate Debasmita PatraDocument1 pageShah Bano Case and Its Impact On Muslim Divorce Laws: Author: Associate Debasmita PatraSinghNo ratings yet

- Shah Bano Case GistDocument3 pagesShah Bano Case GistMelissa PandaNo ratings yet

- M H M L: Aintenance Under Indu AND Uslim AWDocument5 pagesM H M L: Aintenance Under Indu AND Uslim AWStudy AllyNo ratings yet

- Mohd. Ahmed Khan V. Shah Bano Begum and OrsDocument12 pagesMohd. Ahmed Khan V. Shah Bano Begum and OrsДlbeenД WaliNo ratings yet

- Muslim Women (Protection of Rights On Divorce) ActDocument13 pagesMuslim Women (Protection of Rights On Divorce) ActPritam ChattopadhyayNo ratings yet

- Explain The Concept of Nafaqa Under Muslim Law in India: Symbiosis Law School, NOIDADocument4 pagesExplain The Concept of Nafaqa Under Muslim Law in India: Symbiosis Law School, NOIDAFaraz ahmad KhanNo ratings yet

- A Critical Analysis of The Shah Bano CasDocument7 pagesA Critical Analysis of The Shah Bano Casvijaya choudharyNo ratings yet

- Concept Maintenance Under Various Personal LawsDocument11 pagesConcept Maintenance Under Various Personal LawsVaibhavi ModiNo ratings yet

- Family LawDocument12 pagesFamily LawArhum KhanNo ratings yet

- Danial Latifi Vs Union of India (Air 2001 SC 3958) : Family LawDocument12 pagesDanial Latifi Vs Union of India (Air 2001 SC 3958) : Family LawDhruv BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- From (Adwait Singh (Singh - Adwait@gmail - Com) ) - ID (132) - A Critical Analysis of The Shah Bano CaseDocument16 pagesFrom (Adwait Singh (Singh - Adwait@gmail - Com) ) - ID (132) - A Critical Analysis of The Shah Bano CaseRaqesh MalviyaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To MaintenanceDocument6 pagesIntroduction To MaintenanceJoel SenapathiNo ratings yet

- Assignment Family LawDocument6 pagesAssignment Family LawkunishkaNo ratings yet

- Family Law Final DraftDocument19 pagesFamily Law Final Draftnishit gokhruNo ratings yet

- Shah Bano Case-ModifiedDocument10 pagesShah Bano Case-ModifiedNameeta PathakNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis - Writing SampleDocument4 pagesCase Analysis - Writing Sampleishagk002No ratings yet

- Muslim Wife and MaintenanceDocument6 pagesMuslim Wife and MaintenanceHARSH KUMARNo ratings yet

- Maintenance in Muslim LawDocument12 pagesMaintenance in Muslim LawVaibhavNo ratings yet

- Assignment Family Law-IIDocument3 pagesAssignment Family Law-IIwritetobiswajitdasNo ratings yet

- Family LawDocument14 pagesFamily LawRohit Srivastava R 51No ratings yet

- Maintenance of Wife and Children Under Muslim LawDocument7 pagesMaintenance of Wife and Children Under Muslim LawRadha ShawNo ratings yet

- WL End-Term AssignmentDocument12 pagesWL End-Term AssignmentMohd Natiq KhanNo ratings yet

- Muslim Personal LawDocument11 pagesMuslim Personal Lawisha04tyagiNo ratings yet

- 10 - Chapter 4 - 3 PDFDocument30 pages10 - Chapter 4 - 3 PDFPritam AnantaNo ratings yet

- Unit 5Document9 pagesUnit 5saurav sharmaNo ratings yet

- Mohd Ahmed Khan Vs Shah Bano BegumDocument4 pagesMohd Ahmed Khan Vs Shah Bano BegumVartika OjhaNo ratings yet

- Uniform Civil Code and Gender JusticeDocument13 pagesUniform Civil Code and Gender JusticeS.P. SINGHNo ratings yet

- Case Commentary Shah BanoDocument12 pagesCase Commentary Shah BanoDeboo X XavierNo ratings yet

- Maintenence PDFDocument8 pagesMaintenence PDFVishakaRajNo ratings yet

- Maintenance Family LawDocument14 pagesMaintenance Family LawMohammad ArishNo ratings yet

- 217047-Shantanu Awasthi - Danial Latifi v. Union of India & Ors.Document15 pages217047-Shantanu Awasthi - Danial Latifi v. Union of India & Ors.Shantanu AwasthiNo ratings yet

- Family Law Sem 4 Assignment (Mohd Kamran Ansari 20BLW039)Document9 pagesFamily Law Sem 4 Assignment (Mohd Kamran Ansari 20BLW039)Mo Kamran AnsariNo ratings yet

- Case Name:: Mohd. Ahmed Khan Vs Shah Bano Begum and OrsDocument6 pagesCase Name:: Mohd. Ahmed Khan Vs Shah Bano Begum and OrsruhiNo ratings yet

- Family Law Final DraftDocument22 pagesFamily Law Final Draftnishit gokhruNo ratings yet

- Uniform Civil CodeDocument4 pagesUniform Civil Codeaasthakadam16No ratings yet

- Triple Talaq EssayDocument20 pagesTriple Talaq EssayzishanNo ratings yet

- Muslim Law MaintenanceDocument83 pagesMuslim Law Maintenancesarthu100% (1)

- Case Analysis - Danial Latifi vs. Union of India - Indian Law PortalDocument7 pagesCase Analysis - Danial Latifi vs. Union of India - Indian Law PortalGaurav ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Maintenance During IddatDocument4 pagesMaintenance During IddatAadhityaNo ratings yet

- Moot Court 1Document11 pagesMoot Court 1Piku NaikNo ratings yet

- Disciplinary CommitteeDocument10 pagesDisciplinary Committeeakash tiwari100% (1)

- Shah Bano Case - IpleadersDocument22 pagesShah Bano Case - IpleadersPiku NaikNo ratings yet

- NotesDocument16 pagesNotesPiku NaikNo ratings yet

- NotesDocument20 pagesNotesPiku NaikNo ratings yet

- Land Laws Study Material 4th Sem NotesDocument32 pagesLand Laws Study Material 4th Sem NotesRitika100% (2)

- Land Laws Study Material 4th Sem NotesDocument32 pagesLand Laws Study Material 4th Sem NotesRitika100% (2)

- Civil Procedure Code & Limitation Law Ebook & Lecture Notes PDF Download (Studynama - Com - India's Biggest Website For Law Study Material Downloads)Document119 pagesCivil Procedure Code & Limitation Law Ebook & Lecture Notes PDF Download (Studynama - Com - India's Biggest Website For Law Study Material Downloads)Vinnie Singh100% (6)

- Explain in Detail All Types of Trademarks With Related Case LawsDocument5 pagesExplain in Detail All Types of Trademarks With Related Case LawsPiku NaikNo ratings yet

- T2-1819 (76) Diaz and Timbol v. Secretary of Finance - VILLANUEVADocument1 pageT2-1819 (76) Diaz and Timbol v. Secretary of Finance - VILLANUEVACJVNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court: Francisco A. Puray, Sr. For Petitioners. Gabriel N. Duazo For Private RespondentDocument4 pagesSupreme Court: Francisco A. Puray, Sr. For Petitioners. Gabriel N. Duazo For Private RespondentWonder WomanNo ratings yet

- Agpalo Chap - VI NatureAndCreationOfAttorney-ClientRelationshipDocument5 pagesAgpalo Chap - VI NatureAndCreationOfAttorney-ClientRelationshipGelo MVNo ratings yet

- Gift Tax in BangladeshDocument16 pagesGift Tax in BangladeshMd Al AminNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Sandueta v. RoblesDocument3 pagesHeirs of Sandueta v. RoblesPaul Joshua SubaNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of WaiverDocument3 pagesAffidavit of WaiverAhmad AbduljalilNo ratings yet

- Contract Cre IIDocument14 pagesContract Cre IIRam Kumar YadavNo ratings yet

- JurisprudenceDocument11 pagesJurisprudencePuneet Tigga100% (1)

- Extradition LawDocument2 pagesExtradition Lawvijaybhaaskar4242No ratings yet

- 09 Gu-Miro v. AdorableDocument2 pages09 Gu-Miro v. Adorableclarence esguerraNo ratings yet

- RP Vs CArwin ConstructionDocument2 pagesRP Vs CArwin ConstructionAyban NabatarNo ratings yet

- Sanders Vs VeridianoDocument2 pagesSanders Vs Veridianogherold benitezNo ratings yet

- ContractDocument11 pagesContractHạnh Anh Ngô NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Usufruct Agreement Sample FormDocument5 pagesUsufruct Agreement Sample FormKar91% (33)

- M. Y. Shareef and Another VS The Honble Judges of The High CourtDocument16 pagesM. Y. Shareef and Another VS The Honble Judges of The High CourtAdv Aiswarya Unnithan100% (1)

- Digest CasesDocument194 pagesDigest Casesbingadanza90% (21)

- BRITISH COUNCIL - Incentivizing FDI & Partnerships in Higher Ed in PH, A Devt BlueprintDocument110 pagesBRITISH COUNCIL - Incentivizing FDI & Partnerships in Higher Ed in PH, A Devt BlueprintbequillocaryljaneNo ratings yet

- Appointment Letter 1 193Document4 pagesAppointment Letter 1 193Suprasad DixitNo ratings yet

- COunter Affidavit EstafaDocument7 pagesCOunter Affidavit EstafaCheChe89% (18)

- UNIT.6 - HR - Feb To Jun 2018Document28 pagesUNIT.6 - HR - Feb To Jun 2018Uday GowdaNo ratings yet

- Prize Acceptance Form and Release Form (Consolation)Document2 pagesPrize Acceptance Form and Release Form (Consolation)mercurialvaporNo ratings yet

- TELLIE MemorandumDocument7 pagesTELLIE MemorandumKenneth BuñagNo ratings yet

- Application To PEIRA Against High Fees V3.1Document3 pagesApplication To PEIRA Against High Fees V3.1RashidKhanNo ratings yet

- EquityDocument2 pagesEquityzeusapocalypseNo ratings yet

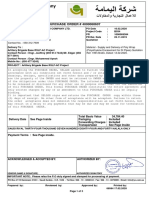

- Al-Yamama Company: PURCHASE ORDER # 4000068607Document3 pagesAl-Yamama Company: PURCHASE ORDER # 4000068607Dusngi MoNo ratings yet

- SUCCESSION Intestate NotesDocument11 pagesSUCCESSION Intestate NotesnelfiamieraNo ratings yet

- Part A JFC2001 Law For FCOs Inspectors and Other Enforcement OfficialsDocument96 pagesPart A JFC2001 Law For FCOs Inspectors and Other Enforcement OfficialssaideroupaNo ratings yet

- Reply To Position Paper Revised1Document9 pagesReply To Position Paper Revised1Gladys Kaye Chua100% (6)

- Syllabus Remedial Law Review I 1St Semester CY 2021 2022Document67 pagesSyllabus Remedial Law Review I 1St Semester CY 2021 2022Sam LagoNo ratings yet

- CSC Resolution No 000828Document3 pagesCSC Resolution No 000828joreyvilNo ratings yet