Professional Documents

Culture Documents

18 A Strength and Conditioning Model For Female Collegiate Cheerleader

Uploaded by

Jeisson RodriguezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

18 A Strength and Conditioning Model For Female Collegiate Cheerleader

Uploaded by

Jeisson RodriguezCopyright:

Available Formats

© National Strength and Conditioning Association

Volume 26, Number 6, pages 16–21

Keywords: cheerleading; sports-specific training; periodization

A Strength and Conditioning Model

for a Female Collegiate Cheerleader

Erika P. Goodwin, MS, Kent J. Adams, PhD, CSCS, and Jennifer Shelburne

University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky

Mark DeBeliso, PhD

Boise State University, Boise, Idaho

balance, and high levels of technical ankle sprains, lower-leg, low-back, and

summary skill and coordination (5, 8, 9). Fur- rotator-cuff injuries (5, 8–12). Further-

thermore, a mastery of gymnastics more, practices and performances typi-

Cheerleading is a sport which is and dance is needed for optimal per- cally occur in unfavorable circum-

formance. stances such as hard wooden floors,

highly competitive, physically and bumpy grass fields, and possibly cold

psychologically demanding, and At many collegiate institutions, cheer- and wet conditions, and cheerleaders

leading is housed in the athletic de- face a myriad of distractions such as

rewarding. Comprehensive condi- partment, and cheerleaders are recruit- crowds, music, and other cheerleaders

ed and are on scholarship. College and nearby. Therefore, proper supplemental

tioning and recovery is a must for grade school cheerleaders now com- training is important to physically pre-

optimal performance and injury pete in high-profile, nationally tele- pare these athletes throughout their

vised championship competitions every training year to maximize skill and con-

prevention. This article proposes a year. To compete, a team must perfect- ditioning levels for the competition sea-

ly perform many skills, including elite son and minimize injuries (5, 6, 8–10,

model to help guide the individu- gymnastic moves, compacted into an 12).

alized strength and conditioning intense 2-minute and 15-second rou-

tine. One mistake in performance is Like gymnastics, cheerleading requires

program of an elite female colle- often the difference between the na- high levels of strength and power rela-

tional champion and the runner-up, so tive to body mass to generate a high rate

giate cheerleader preparing for na- the physical and psychological stress of force development and withstand the

tional competition. runs high (3, 11). However, as in gym- eccentric loading of one’s own body

nastics, skill training alone will not ad- weight to successfully perform the tum-

equately prepare cheerleaders for the bling and throwing skills (6, 12). High

heerleading has moved off the competitive demands of their sport (6, strength levels are also required to push

C sidelines into a league of its

own. It no longer consists of

pep-squad members whose sole pur-

12).

Because cheerleaders train and cheer

and hold other cheerleaders overhead

when performing stunts.

pose is to lead the crowd in cheering through football and basketball seasons, Strength training is vital to better

on their school’s sports teams to victo- these athletes rarely get a rest from skill prepare the athlete for the peak sea-

ry. Today, cheerleading is recognized practices. This high amount of repeti- son, as well as reduce the chance of

as a sport that requires strength, tive practice and performance creates an injuries during the athlete’s critical

power, endurance, flexibility, agility, increased risk for injuries, especially practice and performance sessions (6,

16 December 2004 • Strength and Conditioning Journal

8, 9). Muscular hypertrophy, howev-

er, is typically not the goal of strength

training for female cheerleaders, be-

cause leanness and small body size are

keys in maintaining high relative

strength levels for competitive per- Figure. The cheerleading training year.

formance (12, 13). To minimize hy-

pertrophy in the cheerleader, strength

and conditioning professionals rec- season, and stage II preseason. The per- out is held during this active rest—

ommend strength training with heav- formance phase includes the high-im- physical and psychological rejuvena-

ier loads with fewer repetitions and pact season and peak season. The overall tion is key. Usually, the team meets

longer rest periods (7, 12). Cheer- goal of strength and conditioning train- for only 1 intense week each month

leaders, like gymnasts and dancers, ing for a cheerleader is to maximize to orient themselves with each other

also need to develop and maintain ex- muscular strength, power, and en- and prepare for cheerleading camp.

treme levels of flexibility and be in durance relative to body mass while The emphasis of training is on gener-

peak anaerobic condition to perform minimizing hypertrophy. Anaerobic al conditioning and overall muscular

optimally during their explosive, power and endurance, lactate tolerance, and cardiovascular fitness on an indi-

high-impact, glycolytic, and techni- and flexibility also need to be opti- vidual-need basis. As with other

cal routines (4, 6). mized. sports teams, top performers in

cheerleading are encouraged to re-

The purpose of this article is to pro- Because of the high levels of physical turn from the off-season with excel-

pose a model to help guide the indi- and psychological stress cheerleaders lent base conditioning, ready to start

vidualized strength and conditioning endure, they (like other athletes) must formal training.

program of an elite female collegiate pay critical attention to program de-

cheerleader preparing for national sign to reduce the likelihood of over- Stage I Preseason

competition. This model may not be training. Crucial to monitoring the The training year begins with stage I

appropriate for novice high school athlete is a personal journal the cheer- preseason (July and August), which

cheerleaders or college cheerleaders leader is asked to keep. This journal consists of more intensive weeklong

who may not be physically prepared encompasses such things as training, practices for cheerleading-camp prepa-

for the demands of this level of condi- sleep, dietary habits, and other issues ration and one or two 4-day cheerlead-

tioning. Also, because of variation in that could be key to her readiness to ing camps in the first 2 weeks of Au-

cheerleading task specificity, male train and compete. This type of record, gust. Cheerleading camps are designed

cheerleaders would not typically fol- along with an emphasis on communi- to work on necessary basic skills and

low this plan but would develop a cation between the coach and the compete against other teams to assess

training model based on their individ- cheerleader, helps monitor training the teams’ beginning potential and

ual-needs analysis. and recovery status and guide individ- skill level, much like that of a “scrim-

ualized manipulations in program de- mage.” Outside of camp preparation,

The time of year of the national-level sign throughout the year that help op- stage I preseason has minimal skill

competitions vary depending on the timize performance. practice; therefore, the cheerleaders

cheerleaders’ age, school attended, and should concentrate on strength train-

preferred nationals’ association; there- Conditioning Phase ing and adequate rest and recovery

fore, the peak seasons vary. This model (e.g., sleep, nutrition, massage). As in

uses the month of April as the peak Off-Season gymnastics (12), exercise selection

competitive month for a college cheer- The training year and conditioning should focus on the major muscle

leader attending the National Cheer- phase begins after the team is chosen groups and movements specific to

leaders Association National Champi- (usually late April), with the off-sea- cheerleading as well as strengthening

onship in Daytona Beach, FL. In this son months consisting of May and any problematic areas (e.g., ankle,

model (Figure), the cheerleading year is June. Because cheerleaders are ex- lower leg, low back, rotator cuff ) to

divided into 2 phases, the conditioning pected to be actively performing dur- help prevent initial injury (i.e., preha-

phase and the performance phase. ing football and basketball seasons bilitation).

Within these phases are 5 general train- and then immediately peak for com-

ing stages. The conditioning phase con- petition, this off-season is a very im- To optimize strength (7, 12, 13), repe-

sists of the off-season stage, stage I pre- portant rest period. No formal work- titions per set should be kept in the

December 2004 • Strength and Conditioning Journal 17

Table 1

Sample Stage I Preseason Training Week

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday

Jump rope (5 min) Plyometrics (UB) Rest Jump rope (5 min) Plyometrics (UB) Rest Rest

Medicine ball. Medicine-ball drop,

Plyometrics (LB) Plyometrics (LB) catch, and throw.

Squat jumps with Weights (UB) Tuck jumps bring-

arms extending External rotation ing knees into Weights (UB)

overhead for each Side lateral raise chest. Rear delt raises

jump. DB incline press* Straddle jumps. External rotation

Broad jumps with Close-grip press* DB flat press*

arms extending Lat pull-down* Weights (LB) Pull-up*

overhead. Seated row* Front squat* DB shoulder press*

Triceps press-down Deadlift* Bar dips

Weights (LB) Bar curl DB step-up at 12 DB curl

Back squat* Wrist in.* Wrist

Stiff-leg deadlift* extension/flex Calf (toe) raise extension/flex

Calf (toe) raise Reverse toe raise

Reverse toe raise Sprints Sprints

4 × 400 m Abs (crunch,V-up) 8 × 200 m

Abs (crunch,V-ups)

Note: UB = upper body, LB = lower body, DB = dumbbell. Plyometrics performed for 3 × 8–10 contacts with a 3- to 5-minute rest between sets. * in-

dicates strength-training intensity on primary exercises at 3–5 × 4–6 repetition maximum (RM) with a 3- to 5-minute rest between sets. Secondary

exercises performed at 3 × 6–8 RM with about a 2-minute rest between sets. Sprints performed at 75–85% intensity (no straining) with a 3-minute

rest between bouts.

4–6 range of the repetition maximum performed for 3 sets of 8–10 repetitions work should be performed with cau-

(RM) continuum on primary exercises, (contacts) before the strength-training tion, for it may compromise the ex-

with an introductory resistance in the workout are included to prepare the pression of muscular power necessary

first weeks of the stage that allows cheerleader for increasingly intense skill- for optimal cheer-routine perfor-

completion of the specified set while specific practices that require high power mance (6). Because flexibility is a

still being able to complete about 2 output. Plyometric-based relays and critical requirement of a cheerleader’s

more repetitions (i.e, not training to games such as those discussed by Bompa performance, each workout should be

failure). As the cheerleader acclimates (1, 2) are also recommended for the be- completed with stretching exercises

to the formal strength-training work- ginning of some workouts. Games are a (e.g., static stretching, proprioceptive

outs, intensity increases to a true great way to develop power and team- neuromuscular facilitation, active

4–6RM (i.e., near failure to failure). work crucial to the cheerleader’s com- isolate stretching) and followed by a

Set range is 3–5 per movement with a petitive performance while including cool-down (e.g., light stretches, re-

3- to 5-minute rest between sets, again fun and variety into the training regi- laxation drills). Table 1 depicts a sam-

to focus on optimizing strength (7). men (1, 2). ple training week during stage I pre-

Secondary exercises are performed for season.

3 × 6–8 repetitions with about 2 min- Rotator-cuff exercises are performed

utes of rest between sets. before the upper-body workouts for 3 Stage II Preseason

sets of 10 repetitions. Abdominal Stage II preseason includes Septem-

Workouts should be 4 times a week be- movements (e.g., crunches, V-ups) ber–December. This is the point of the

ginning with a 5- to 10-minute warm-up are performed 2 days a week for 3 sets season when the team practices 3–4

(e.g., jump rope, jogging, stair stepper). of 20 repetitions each. In addition, times a week for 3–4 hours each prac-

Low- to moderate-intensity plyometrics light-to-moderate anaerobic training, tice, cheers football and basketball

(e.g., squat jumps, broad jumps, tuck such as sprints or cycling intervals, is games, and does appearances and per-

jumps, medicine-ball throw and catch) performed 2 days a week. Aerobic formances in the local community. Be-

18 December 2004 • Strength and Conditioning Journal

Table 2

Sample Stage II Preseason Training Week

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday

Jump rope (5 min) Sprints Weights Jump rope (5 min) Sprints Game day Rest

4–6 × 400 m at External rotation Medicine-ball 4–6 × 200 m at or general

Plyometrics about 80–90% in- Side lateral raise drop, catch, and 90–95% intensity practice.

Drop jump with tensity with 3- to DB incline press* throw. with 3- to 5-min

hurdle hops. 5-min rest be- Close-grip press* Box jumps with rest between

Drop push-up tween bouts. Close-grip pull- 10- to 12-m bouts.

onto box. down* sprint.

Seated row* or Rest

Weights Bar curl Weights

Back squat* Jump squat* at

Push press* 20–40% of Mon-

Lat pull-down* day’s squat rate.

Calf (toe) raise Deadlift*

Reverse to raise Close-grip press*

Wrist Wide-grip pull-

extension/flex up*

Rear delt raises

Abs (crunch,V-up)

Abs (crunch, hang-

ing leg raise)

Note: DB = dumbbell. Plyometrics performed for 3 × 5–8 contacts. * indicates strength-training intensity on primary exercises at 4–6 × 2–5 repeti-

tion maximum (RM) with a 3- to 5-minute rest between sets. Secondary exercises performed at 3 × 6–8 RM with about a 2-minute rest between sets.

cause of the long time period stage II The resistance workouts should de- ualized adjustments in the training

preseason encompasses (about 16 crease to 2–3 times a week because the stress to optimize the response to

weeks), trainers are recommended to regular practice schedule of the cheer- training, performance, and recovery.

use microcycles of 4–6 weeks to add leaders and games they cheer at are Table 2 depicts a sample training week

variation and manipulate the intensity now in session. The amount of during a microcycle used in stage II

and volume of training for optimal strength-training exercises should be preseason.

adaptation and recovery. This also al- reduced, but the anaerobic training

lows additional planned recovery should still be a major conditioning Performance Phase

breaks at Thanksgiving and Christmas tool.

for the cheerleaders to visit home or High-Impact Season

cheer the school’s football team at a The importance of this stage is to gain The next phase of the training year is

bowl event. the skills, strength, and power neces- the performance phase, with the high-

sary for the peak season. All skills impact season consisting of January–

During this time, the focus of strength should be mastered in this time peri- March. The cheerleader team now

training should be on the major mus- od, and the competitive team is cho- practices performing skills in a short

cles used in the cheerleaders’ skills, as sen based on performance during this period of time and practices the 2-

well as the high-risk injury areas. In- stage. Cheerleaders and coaches must minute and 15-second routine on a

tensity is high, with the sets increasing be aware that this is a stressful time regular basis. The high-impact season

(e.g., 4–6) and the repetitions decreas- for cheerleaders. Rest and recovery is a strenuous period with high gly-

ing (e.g., 2–5) on primary exercises. techniques must be emphasized, along colytic and structural demands during

Ballistic movements where the cheer- with increased communication be- repetitive skill and performance prac-

leader accelerates into free space (e.g., tween the coach and the cheerleader tice. The cheerleader should be well

jump squats) are incorporated in some related to individual status. These ac- conditioned to withstand these de-

microcycles to further enhance power. tivities are crucial to making individ- mands at this point.

December 2004 • Strength and Conditioning Journal 19

once they have been reached. A general

Table 3

practice at this point lasts about 3 hours

General Cheerleading Practice Structure During High-Impact Season

(refer to Table 3). This training should

Time Activity give the cheerleader proper strength,

power, endurance, and flexibility to

1500–1520 The team warms up and stretches together, making sure that the mus- perform at peak condition for the com-

cles are ready to meet the demands of repetitive overstretching. petitive month.

1520–1530 The practice then begins with a few “walk-throughs” of the routine.

As if the practices were not enough

This is the only time where no tricks are thrown.

stress on their bodies, the cheerleaders

1530–1600 The team then warms up the appropriate stunts, pyramids, or basket are now also cheering basketball games

tosses for the routine. 2 or 3 times a week, continuing to make

1600–1630 The routine is performed with all the stunts, pyramids, or basket tosses community appearances, and perform-

usually 3 or 4 times with rest periods in between. ing sections of their routines publicly

1630–1700 The team warms up their appropriate standing tumbling or gymnastic to prepare for competition. Overtrain-

skills that are in the routine. ing is a key concern, and the cheerlead-

ers must be monitored and individual

1700–1730 The routine is performed with all standing tumbling, and the running

workouts manipulated as necessary to

tumbling is warmed up during these “run-throughs.”

enhance recovery (4). Communication

1730–1745 Break. between the coach and the cheerleader

1745–1800 The team goes through 2 or 3 “full-out run-throughs” where the rou- about training and recovery status is

tine is performed with all stunting and tumbling skills. again emphasized to help facilitate op-

1800–1830 The conditioning session of 30 minutes is conducted.This includes timal program design. Table 4 is an ex-

skill conditioning (e.g., 10 consecutive standing tucks), body-weight ample of a cheerleader’s week during

exercises (e.g., pushups, crunches, free-standing squat jumps), and the high-impact season.

short sprint work (e.g., line drills) followed by extensive static and

proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitating stretching. Peak Season

The national competition is at the be-

ginning of April. The cheerleader needs

to be in peak condition at this time for

Table 4

A Cheerleader’s Sample Week During High-Impact Season optimal competitive performance. A na-

tional competition is usually a 3-day

Day Activity event including a preliminary round of

all the teams and “Finals” consisting of

Monday 3-h practice on the routine followed by conditioning the top teams in each division. Divisions

Tuesday 2- to 3-h basketball game where the cheerleader is there 1– 1⁄2 h early are determined by the size of school in

for warm-up and to prepare for the pregame traditions the college-level competitions and the

size of team at the high school–level

Wednesday 3-h practice on the routine followed by conditioning

competitions. A large division usually

Thursday 2- to 3-h basketball game where the cheerleader is there 1– 1⁄2 h early

includes about 50 teams during the pre-

for warm-up and to prepare for the pregame traditions

liminary round, and only 10 of those

Friday 3-h practice on the routine followed by conditioning make it to Finals.

Saturday Performance of the routine for the public at a local high school

competition The teams perform their routines for

Sunday A morning appearance for the basketball team’s pep rally followed competition once for preliminaries and

by the 3-h practice on the routine and conditioning once for Finals. They have only 1 time to

make their routine work, which is why

total conditioning is vital. The teams

As the volume of skill practice increases weight room and more on body-weight continue to practice on their skills

throughout the training year, the cheer- strength. The practices during this ses- throughout the competition during

leader will cycle from heavier weight sion are broken down into sections to each break. The peak month includes

lifting to more body-weight training. build up for the maximum demands of not only competition with other teams,

Therefore, she should focus less on the the routine and then maintain them but also try-outs for the upcoming year’s

20 December 2004 • Strength and Conditioning Journal

team—another stressful event. After the ton, J. Potteiger, M.H. Stone, N.A.

peak month, the cheerleaders begin the Ratamess, and T. Triplett-McBride.

off-season. American College of Sports Medicine

position stand on progression models

Conclusion in resistance training for healthy

The sport of cheerleading is highly adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc.

competitive, physically and psycho- 34:364–380. 2002.

logically demanding, and rewarding. 8. Luckstead, E.F., and D.R. Patel. Cata-

Comprehensive conditioning and re- strophic pediatric sports injuries. Pedi-

covery is a must for optimal perfor- atr. Clin. North Am. 49:581–591. Adams

mance and injury prevention. The 2002.

model presented in this article may 9. Luckstead, E.F., A.L. Satran, and D.R. Kent J. Adams is an associate professor of

help guide the individualized training Patel. Sport injury profiles, training Exercise Physiology at the University of

of the elite collegiate female cheer- and rehabilitation issues in American Louisville.

leader. As always, the individual’s spe- sports. Pediatr. Clin. North Am.

cific needs, training status, and re- 49:753–767. 2002.

sponse will dictate the final program 10. Pilkington, J. Cheerleader’s condition-

design. ♦ ing work-out. Mo. J. Health Phys. Edu-

cation Recreation Dance. 10:53–59.

References 2000.

1. Bompa, T.O. Power Training for 11. Rowe, A., S. Wright, J. Nyland, D.N.

Sport–-Plyometrics for Maximum Caborn, and R. Kling. Effect of a 2-

Power Development. Oakville, On- hour cheerleading practice on dy-

tario, Canada: Mosaic Press, 1993. pp. namic postural stability, knee laxity,

77–146. and hamstring extensibility. J. Or-

2. Bompa, T.O. Periodization Training for thop. Sports Phys. Ther. 29:455–462. DeBeliso

Sports. Champaign, IL: Human Kinet- 1999.

ics, 1999. pp. 161–190. 12. Sands, W.A., J.R. McNeal, M. Jemni, Mark DeBeliso is an assistant professor

3. Finkenberg, M.E., J.N. DiNucci, E.D. and T.H. Delong. Should female gym- of Biomechanics at Boise State University.

McCune, and S.L. McCune. Cogni- nasts lift weights? Sportscience.

tive and somatic state anxiety and self- 4(3):1–6. 2000. Available at: http://

confidence in cheerleading competi- www.sportsci.org/jour/0003/was.html.

tion. Percept. Mot. Skills. 75:835–839. Accessed March 16, 2004.

1992. 13. Zatsiorsky, V.M. Science and Practice of

4. Fry, A.C., K. Hakkinen, and W.J. Strength Training. Champaign, IL:

Kraemer. Special considerations in Human Kinetics, 1995. pp. 59–81,

strength training. In: Strength Training 200–220.

for Sport. W.J. Kraemer and K. Hakki-

nen, eds. Malden, MA: Blackwell Sci-

ence, 2002. pp. 135–162.

5. Gottlieb, A. Cheerleaders are athletes Shelburne

too. Pediatr. Nurs. 20:630–633. 1994.

6. Hasegawa, H., J. Dziados, R.U. New- Jennifer Shelburne currently works and

ton, A.C. Fry, W.J. Kraemer, and K. models in the fitness industry and is a for-

Hakkinen. Periodized training pro- mer University of Louisville cheerleader.

grams for athletes. In: Strength Train-

ing for Sport. W.J. Kraemer and K.

Hakkinen, eds. Malden, MA: Black- Goodwin

well Science, 2002. pp. 69–134.

7. Kraemer, W.J., K. Adams, E. Cafarel- Erika P. Goodwin coaches cheerleading

li, G.A. Dudley, C. Dooly, M.S. in the National Cheerleaders Association

Feigenbaum, S.J. Fleck, B. Franklin, High School division and is a former Uni-

A.C. Fry, J.R. Hoffman, R.U. New- versity of Louisville cheerleader.

December 2004 • Strength and Conditioning Journal 21

You might also like

- Make your sports training a real success: Warming-up and recovering afterFrom EverandMake your sports training a real success: Warming-up and recovering afterNo ratings yet

- Chapter 14 - Long Term Athletic Development in GymnasticsDocument12 pagesChapter 14 - Long Term Athletic Development in GymnasticsDDVNo ratings yet

- How To Build Your Weekly Workout Program - Based On The Teachings Of Dr. Andrew Huberman: Elevate Your FitnessFrom EverandHow To Build Your Weekly Workout Program - Based On The Teachings Of Dr. Andrew Huberman: Elevate Your FitnessNo ratings yet

- Speed Training PDFDocument27 pagesSpeed Training PDFDustin SealeyNo ratings yet

- Functional Fitness Concept - FINAL 061120Document16 pagesFunctional Fitness Concept - FINAL 061120cliftoncageNo ratings yet

- Usmc Functional Fitness ConceptDocument16 pagesUsmc Functional Fitness ConceptJakeWillNo ratings yet

- Assignment in P.E.Document6 pagesAssignment in P.E.Ian Dante ArcangelesNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 - Strength and Power PDFDocument76 pagesChapter 8 - Strength and Power PDFDDVNo ratings yet

- Fred Duncan基础体能论文 PDFDocument3 pagesFred Duncan基础体能论文 PDFweiNo ratings yet

- Identifying, Understanding and Training Youth AthletesDocument9 pagesIdentifying, Understanding and Training Youth AthletesAngga AnggaraNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Physical ActivityDocument3 pagesUnderstanding The Physical Activityryan alcantaraNo ratings yet

- Strength and Conditioning For FootballDocument21 pagesStrength and Conditioning For Footballbryce crawfordNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Interscholastic AthleticsDocument4 pagesPhilosophy of Interscholastic AthleticsoathwebNo ratings yet

- Long Term Development in Swimming (Scotland)Document3 pagesLong Term Development in Swimming (Scotland)Clubear ClubearNo ratings yet

- Nico D'Haenen: Athletic Development CoachDocument3 pagesNico D'Haenen: Athletic Development CoachJewelson SantosNo ratings yet

- c1 5 PDFDocument15 pagesc1 5 PDFIuliana PomârleanuNo ratings yet

- Identifying and Developing Elite Hurdlers in The United StatesDocument6 pagesIdentifying and Developing Elite Hurdlers in The United StatesMarco TorreNo ratings yet

- Resistance Training Considerations For The Sport of SquashDocument9 pagesResistance Training Considerations For The Sport of SquashAl100% (1)

- Bompa PeakingDocument18 pagesBompa Peakingtoni_kurkurNo ratings yet

- Haff GG 2004 - Periodizacao Do Treinamento - 2Document15 pagesHaff GG 2004 - Periodizacao Do Treinamento - 2Jean Freitas LimaNo ratings yet

- Preseason Strength Training For Rugby Union - The General and Speci C Preparatory PhasesDocument9 pagesPreseason Strength Training For Rugby Union - The General and Speci C Preparatory PhasesHani Assi100% (1)

- Principles of TrainingDocument6 pagesPrinciples of TrainingVeronica Sadom100% (1)

- Swimmer Development ModelDocument8 pagesSwimmer Development Modelibatch7872No ratings yet

- Dance Fitness: Resource Paper For Dance TeachersDocument9 pagesDance Fitness: Resource Paper For Dance TeachersWill RomeroNo ratings yet

- Training MethodsDocument7 pagesTraining MethodsRISHAV SHUKLANo ratings yet

- XpooooooooooooooorDocument35 pagesXpooooooooooooooorHanxini3No ratings yet

- Strength Training For Young Rugby PlayersDocument5 pagesStrength Training For Young Rugby PlayersJosh Winter0% (1)

- Periodization Training For The Power AthleteDocument5 pagesPeriodization Training For The Power AthleteBeckerNo ratings yet

- Long Term Athlete DevelopmentDocument9 pagesLong Term Athlete DevelopmentLeonardini100% (1)

- 7 Principles of Exercise and Sport TrainingDocument13 pages7 Principles of Exercise and Sport TrainingMelJune Rodriguez IIINo ratings yet

- Physical Training of Greek-Roman Style Wrestlers (12-14 Years) by Cross Fit MeansDocument2 pagesPhysical Training of Greek-Roman Style Wrestlers (12-14 Years) by Cross Fit MeansAgache GigelNo ratings yet

- Total Soccer Conditioning Volume 1 PDFDocument194 pagesTotal Soccer Conditioning Volume 1 PDFtanasa marian100% (1)

- A Coaches Dozen 12 Fundamental Principles For.13Document3 pagesA Coaches Dozen 12 Fundamental Principles For.13Rodulfo AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Strength and Condition ManualDocument18 pagesStrength and Condition ManualHilde CampNo ratings yet

- Strength Training For Young Rugby PlayersDocument10 pagesStrength Training For Young Rugby Playersgeena1980No ratings yet

- Class Xi, Chapter-10, Training and Doping in Sports.Document212 pagesClass Xi, Chapter-10, Training and Doping in Sports.Adi KumarNo ratings yet

- SHS Grade 11: Sports - Principles, Strategies and CoachingDocument12 pagesSHS Grade 11: Sports - Principles, Strategies and Coachingto diaryNo ratings yet

- 12th NotesDocument27 pages12th NotesShabirNo ratings yet

- Orca - Share - Media1681997049430 - 7054806952414938247 - Copy (Repaired)Document56 pagesOrca - Share - Media1681997049430 - 7054806952414938247 - Copy (Repaired)leo carlo primaveraNo ratings yet

- Weight Training - Pre-Adolescent Strength Training - Just Do It!Document4 pagesWeight Training - Pre-Adolescent Strength Training - Just Do It!João P. Tinoco MaiaNo ratings yet

- Specific Physical Training in Elite Male Team.95893Document33 pagesSpecific Physical Training in Elite Male Team.95893Martiniano Vera EnriqueNo ratings yet

- Strength Training For Rugby Union - The General Preparation PhaseDocument21 pagesStrength Training For Rugby Union - The General Preparation PhaseLancelot Enchen100% (2)

- Chapter 9 - Cardio and ESD PDFDocument28 pagesChapter 9 - Cardio and ESD PDFDDVNo ratings yet

- Strength and Conditioning For Grappling Sports.4Document7 pagesStrength and Conditioning For Grappling Sports.4Tom0% (1)

- NSCA Performance Training Journal (Conditioning May 2012)Document27 pagesNSCA Performance Training Journal (Conditioning May 2012)Fitness Tutor for the ACE & NSCA Exams100% (4)

- Principles of TrainingDocument17 pagesPrinciples of Trainingribeiro.aikido4736100% (1)

- Long Term Athlete Development Strategy: Swimming - CaDocument13 pagesLong Term Athlete Development Strategy: Swimming - CaAnonymous GJuRvp9A5TNo ratings yet

- Newton Et Al. (2006) - Strength and Power Training of Australian Olympic SwimmersDocument10 pagesNewton Et Al. (2006) - Strength and Power Training of Australian Olympic SwimmerssilvanNo ratings yet

- Advanced Fitness PDFDocument103 pagesAdvanced Fitness PDFNeto Joaquim100% (3)

- Peterson Et Al, 2004Document6 pagesPeterson Et Al, 2004Bernardo Ravanello da CostaNo ratings yet

- Introduction/Athlete Demographics Age: 21 Gender: Male Sport: Tennis Skill: Volley Physical Parameter: Strength Planning Analysis ResultsDocument1 pageIntroduction/Athlete Demographics Age: 21 Gender: Male Sport: Tennis Skill: Volley Physical Parameter: Strength Planning Analysis ResultsEmma NewberryNo ratings yet

- Mil Athlete Working DraftDocument17 pagesMil Athlete Working DraftSamuelNo ratings yet

- Strength Training For Basketball 2020Document11 pagesStrength Training For Basketball 2020Jean Claude HabalineNo ratings yet

- Long Term Athlete Development, Trainability in Childhood - I BalyiDocument5 pagesLong Term Athlete Development, Trainability in Childhood - I BalyigoodoemanNo ratings yet

- GrXII.U1.PHE SC 30.06.2022Document44 pagesGrXII.U1.PHE SC 30.06.2022Nikita SharmaNo ratings yet

- 10.1519 1533-4287 (2003) 017 0734 Iotpoi 2.0Document5 pages10.1519 1533-4287 (2003) 017 0734 Iotpoi 2.0Stefan KovačevićNo ratings yet

- Dreher Strength ProgramDocument240 pagesDreher Strength ProgramAlfredo QuinonesNo ratings yet

- Dave-Salo - PHD - Conditioning For swimming-Scott-A SÓ FORÇADocument6 pagesDave-Salo - PHD - Conditioning For swimming-Scott-A SÓ FORÇAcesar Teixeira0% (1)

- ASV Program Guide v3.0Document53 pagesASV Program Guide v3.0Mithun LomateNo ratings yet

- Relationship With Josephine BrackenDocument9 pagesRelationship With Josephine BrackenNothingNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1-2Document19 pagesLecture 1-2neri biNo ratings yet

- CVS Series E 1 6 Inch March 2021 1Document16 pagesCVS Series E 1 6 Inch March 2021 1iqmpslabNo ratings yet

- English 9 Determiners PDF CbseDocument9 pagesEnglish 9 Determiners PDF CbseAarav SakpalNo ratings yet

- ProgramDetails PDF 134Document2 pagesProgramDetails PDF 134samyakgaikwad12No ratings yet

- Brosur HP Designjet Z5400 PDFDocument2 pagesBrosur HP Designjet Z5400 PDFMustamin TajuddinNo ratings yet

- Word As "BUNDLES" of MeaningDocument19 pagesWord As "BUNDLES" of MeaningDzakiaNo ratings yet

- The Paradox of The Duty of Perfection in The Doctrine of Ibn 'Arabi PDFDocument7 pagesThe Paradox of The Duty of Perfection in The Doctrine of Ibn 'Arabi PDFyusuf shaikhNo ratings yet

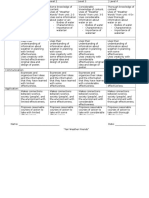

- Science Culminating Task RubricDocument2 pagesScience Culminating Task Rubricapi-311644452No ratings yet

- IR Sensor Infrared Obstacle Sensor Module Has Builtin IR Transmitter and IR Receiver That Sends Out IR Energy and Looks ForDocument12 pagesIR Sensor Infrared Obstacle Sensor Module Has Builtin IR Transmitter and IR Receiver That Sends Out IR Energy and Looks ForRavi RajanNo ratings yet

- Sociologia Şi Ştiinţa Naţiunii În Doctrina Lui Dimitrie GustiDocument35 pagesSociologia Şi Ştiinţa Naţiunii În Doctrina Lui Dimitrie GustiSaveanu RazvanNo ratings yet

- Pic 24Document368 pagesPic 24alin0604No ratings yet

- Lumawig The Great Spirit - IgorotDocument2 pagesLumawig The Great Spirit - IgorotTristhan MauricioNo ratings yet

- JLG Skytrak Telehandler 6042 Operation Service Parts ManualsDocument22 pagesJLG Skytrak Telehandler 6042 Operation Service Parts Manualschristyross211089ntz100% (133)

- NOAH STANTON - 3.1.3 and 3.1.4 Creating Graphs and Finding SolutionsDocument7 pagesNOAH STANTON - 3.1.3 and 3.1.4 Creating Graphs and Finding SolutionsSora PhantomhiveNo ratings yet

- How To Represent Geospatial Data in SDMX 20181022Document47 pagesHow To Represent Geospatial Data in SDMX 20181022scorpio1878No ratings yet

- Christmas Book 2004Document98 pagesChristmas Book 2004Ron BarnettNo ratings yet

- Strength Training For Young Rugby PlayersDocument5 pagesStrength Training For Young Rugby PlayersJosh Winter0% (1)

- Inventory Adjustment Template IifDocument6 pagesInventory Adjustment Template IifABDULKARIM HAJI YOUSUFNo ratings yet

- Flash Assignment Final PDFDocument3 pagesFlash Assignment Final PDFGaryNo ratings yet

- Marketing Mix ModelingDocument14 pagesMarketing Mix ModelingRajesh KurupNo ratings yet

- Blastam Statistics CheatsheetDocument1 pageBlastam Statistics CheatsheetHanbali Athari100% (1)

- Blair For War Crimes Icc 2Document110 pagesBlair For War Crimes Icc 2Her Royal Highness Queen Valerie INo ratings yet

- VungleDocument14 pagesVunglegaurdevNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 1Document8 pagesJurnal 1Dela Amelia Nur SalehaNo ratings yet

- KATO Design Manual HighDocument98 pagesKATO Design Manual HighJai Bhandari100% (1)

- s1 English Scope and Sequence ChecklistDocument18 pagess1 English Scope and Sequence Checklistapi-280236110No ratings yet

- Electrical Submersible Pumps and Motors: Pleuger Water-Filled Design Byron Jackson Oil-Filled DesignDocument8 pagesElectrical Submersible Pumps and Motors: Pleuger Water-Filled Design Byron Jackson Oil-Filled DesignGunjanNo ratings yet

- Science of Being - 27 Lessons (1-9) - Eugene FersenDocument202 pagesScience of Being - 27 Lessons (1-9) - Eugene FersenOnenessNo ratings yet

- Chair Yoga: Sit, Stretch, and Strengthen Your Way to a Happier, Healthier YouFrom EverandChair Yoga: Sit, Stretch, and Strengthen Your Way to a Happier, Healthier YouRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- Aging Backwards: Reverse the Aging Process and Look 10 Years Younger in 30 Minutes a DayFrom EverandAging Backwards: Reverse the Aging Process and Look 10 Years Younger in 30 Minutes a DayNo ratings yet

- Boundless: Upgrade Your Brain, Optimize Your Body & Defy AgingFrom EverandBoundless: Upgrade Your Brain, Optimize Your Body & Defy AgingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (67)

- Functional Training and Beyond: Building the Ultimate Superfunctional Body and MindFrom EverandFunctional Training and Beyond: Building the Ultimate Superfunctional Body and MindRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1)

- Strong Is the New Beautiful: Embrace Your Natural Beauty, Eat Clean, and Harness Your PowerFrom EverandStrong Is the New Beautiful: Embrace Your Natural Beauty, Eat Clean, and Harness Your PowerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Relentless: From Good to Great to UnstoppableFrom EverandRelentless: From Good to Great to UnstoppableRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (789)

- Somatic Exercises for Beginners: Transform Your Life in 30 Days with Personalized Exercises for Body and MindFrom EverandSomatic Exercises for Beginners: Transform Your Life in 30 Days with Personalized Exercises for Body and MindNo ratings yet

- True Yoga: Practicing With the Yoga Sutras for Happiness & Spiritual FulfillmentFrom EverandTrue Yoga: Practicing With the Yoga Sutras for Happiness & Spiritual FulfillmentRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (22)

- The Power of Fastercise: Using the New Science of Signaling Exercise to Get Surprisingly Fit in Just a Few Minutes a DayFrom EverandThe Power of Fastercise: Using the New Science of Signaling Exercise to Get Surprisingly Fit in Just a Few Minutes a DayRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Power of 10: The Once-A-Week Slow Motion Fitness RevolutionFrom EverandPower of 10: The Once-A-Week Slow Motion Fitness RevolutionRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (11)

- Muscle for Life: Get Lean, Strong, and Healthy at Any Age!From EverandMuscle for Life: Get Lean, Strong, and Healthy at Any Age!Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (22)

- Not a Diet Book: Take Control. Gain Confidence. Change Your Life.From EverandNot a Diet Book: Take Control. Gain Confidence. Change Your Life.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (128)

- Peak: The New Science of Athletic Performance That is Revolutionizing SportsFrom EverandPeak: The New Science of Athletic Performance That is Revolutionizing SportsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (97)

- The Yogi Code: Seven Universal Laws of Infinite SuccessFrom EverandThe Yogi Code: Seven Universal Laws of Infinite SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (104)

- Beastmode Calisthenics: A Simple and Effective Guide to Get Ripped with Bodyweight TrainingFrom EverandBeastmode Calisthenics: A Simple and Effective Guide to Get Ripped with Bodyweight TrainingNo ratings yet

- Martial Grit: Real Fighting Fitness (On a Budget)From EverandMartial Grit: Real Fighting Fitness (On a Budget)Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 8 Weeks to 30 Consecutive Pull-Ups: Build Your Upper Body Working Your Upper Back, Shoulders, and Biceps | at Home Workouts | No Gym Required |From Everand8 Weeks to 30 Consecutive Pull-Ups: Build Your Upper Body Working Your Upper Back, Shoulders, and Biceps | at Home Workouts | No Gym Required |No ratings yet

- Pranayama: The Yoga Science of BreathingFrom EverandPranayama: The Yoga Science of BreathingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- Primal Endurance: Escape chronic cardio and carbohydrate dependency and become a fat burning beast!From EverandPrimal Endurance: Escape chronic cardio and carbohydrate dependency and become a fat burning beast!Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (8)

- Enter The Kettlebell!: Strength Secret of the Soviet SupermenFrom EverandEnter The Kettlebell!: Strength Secret of the Soviet SupermenRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (29)

- The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali: The Final Guide for the Study and Practice of Patanjali's Yoga SutrasFrom EverandThe Yoga Sutras of Patanjali: The Final Guide for the Study and Practice of Patanjali's Yoga SutrasNo ratings yet

- Body by Science: A Research Based Program for Strength Training, Body building, and Complete Fitness in 12 Minutes a WeekFrom EverandBody by Science: A Research Based Program for Strength Training, Body building, and Complete Fitness in 12 Minutes a WeekRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (85)

- End Everyday Pain for 50+: A 10-Minute-a-Day Program of Stretching, Strengthening and Movement to Break the Grip of PainFrom EverandEnd Everyday Pain for 50+: A 10-Minute-a-Day Program of Stretching, Strengthening and Movement to Break the Grip of PainRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- The Dark Arts of Tantric Yoga and Other Timeless SecretsFrom EverandThe Dark Arts of Tantric Yoga and Other Timeless SecretsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- Kundalini Awakening: An Essential Guide to Achieving Higher Consciousness, Opening the Third Eye, Balancing Your Chakras, and Understanding Spiritual EnlightenmentFrom EverandKundalini Awakening: An Essential Guide to Achieving Higher Consciousness, Opening the Third Eye, Balancing Your Chakras, and Understanding Spiritual EnlightenmentRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (34)

- Calisthenics: 30 Days to Ripped: 40 Essential Calisthenics & Body Weight Exercises. Get Your Dream Body Fast With Body Weight Exercises and CalisthenicsFrom EverandCalisthenics: 30 Days to Ripped: 40 Essential Calisthenics & Body Weight Exercises. Get Your Dream Body Fast With Body Weight Exercises and CalisthenicsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Wall Pilates: Quick-and-Simple to Lose Weight and Stay Healthy. A 30-Day Journey with + 100 ExercisesFrom EverandWall Pilates: Quick-and-Simple to Lose Weight and Stay Healthy. A 30-Day Journey with + 100 ExercisesNo ratings yet

- The Strength and Conditioning Bible: How to Train Like an AthleteFrom EverandThe Strength and Conditioning Bible: How to Train Like an AthleteNo ratings yet