Professional Documents

Culture Documents

SSRN Id3714080

Uploaded by

Shaikh Fazlur RahmanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

SSRN Id3714080

Uploaded by

Shaikh Fazlur RahmanCopyright:

Available Formats

A Paper Presented at the Global Strategy and Emerging Markets Conference, Boston,

Massachusetts, 2017

Title: Emerging multinationals innovating in emerging markets:

motives and the role of location advantages and disadvantages

Authors: Peter Zámborský* and Igor Ingršt**

Corresponding author: p.zamborsky@auckland.ac.nz

Affiliations: *University of Auckland Business School; **University of Auckland, New

Zealand & Masaryk University, Czech Republic

Abstract

This paper analyzes motives for investment by emerging multinationals in R&D and

innovation-intensive activities in emerging markets. We focus on innovation by non-Chinese

emerging MNEs in Central and Eastern Europe. We aim to contribute to the debates on the

potentially different motives for investment and behaviors of MNEs from emerging and

advanced countries (Narula, 2012; Di Minin, Zhang and Gammeltoft, 2012; Giuliani,

Gorgoni, Guenther and Rabelloti, 2014; Cuervo-Cazurra and Ramamurti, 2014) and how

MNEs’ locational decisions in terms of innovation in advanced vs emerging countries differ

depending on their country of origin.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3714080

Theory

On a broad level, our theory builds on the distinction between location advantages (both of

the home and the host country), non-transferable (or location-bound) firm-specific

advantages and internationally transferable (or non-location bound) firm-specific advantages

(Verbeke, 2013). Location advantages, in general, can be classified according to motives for

a firm to conduct economic activity in that location. The most commonly mentioned are

natural resource seeking, market seeking, strategic resource seeking, and efficiency seeking

motives (Verbeke 2013), although some authors refer to other motives such as knowledge

seeking (Chung and Alcácer, 2002; Zámborský and Jacobs, 2017).

However, while this conceptual framework is appropriate for advanced economy MNEs,

multinationals from emerging markets often struggle with firm-specific and location

disadvantages rather than advantages (of their home country) and develop strategies to

transform disadvantages into advantages (Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc, 2008). Extant research

has highlighted firm-specific disadvantages of emerging multinationals: smaller size, less

cutting-edge technology and resources that are less sophisticated and capabilities that are less

developed (Wells, 1983; Dawar & Frost, 1999). Additionally, negative perceptions of the

country-of-origin may create a disadvantageous image among customers (Bilkey and Nes,

1982) and difficult home-country institutional environments may also be a disadvantage

(Khanna and Palepu, 1997).

In our research, we focus on the role of location advantages and disadvantages relevant to

emerging multinationals’ motivations for decisions to invest in innovation in emerging

markets. Both motivations and the underlying country-of-origin factors affecting international

innovation strategies of emerging multinationals in emerging markets are poorly understood.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3714080

The motives for international innovation investment in general are typically linked to market

seeking and strategic resource seeking motives, sometimes with an element of efficiency

seeking motive. Håkanson and Nobel (1991), in a pioneering study of Swedish multinationals,

recognize five types of activity motives for foreign R&D establishment: 1) Market oriented

units; 2) production support units for foreign R&D units; 3) politically motivated units; 4)

multi-motive units can be set up or retained based on combinations of the considerations and

motives mentioned above; 5) knowledge-seeking firms will look for R&D epicentres in areas

of their strategic interest to catch up with their competitors’ innovation levels, broaden their

knowledge portfolios and also search for technical diversity in different regional market needs.

Other scholars focusing on developed country multinationals identified market-driven and

technology-driven motives (Zedtwitz and Gassmann, 2002); technology exploration vs.

exploitation motives and push/pull factors (Ambos and Ambos, 2011).

Di Minin et al. (2012), in a study of Chinese investment in R&D in Europe, find that there are

important differences between the R&D internationalisation processes of multinationals from

developed and emerging economies. They suggest that EMNEs have concentrated on seeking

strategic assets and resources (especially research and development) when entering advanced

economic markets to acquire resources to build a competitive advantage.

Giuliani et al. (2014), in another study focusing on emerging vs advanced MNE investment in

Europe, have created a typology of MNE subsidiaries based on the following dimensions:

(1) The degree to which MNEs transfer and/or receive knowledge to/from their headquarters

and to/from other subsidiaries (intra-corporate knowledge transfer);

(2) The level of locally embedded innovative activities (generating value for the MNE and the

local context as well), including formation of local innovative ties (collaborations) and

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3714080

innovation activity developed locally by the subsidiary (internally and independently from the

HQ and sister firms).

They find that EMNEs and AMNEs often undertake different strategies for tapping into local

knowledge and for transferring it within the company (e.g., EMNEs tend to be more pro-

active/entrepreneurial and generate more patents). Their study implies that the differences

between EMNEs and AMNEs are often blurred. While AMNEs accounted for the vast majority

of passive subsidiaries in the sample, they also accounted for a substantial share of predatory

(30%) and dual (40%) subsidiaries.

However, in both Di Minin et al. (2012) and Giuliani et al. (2014), it is not clear how their

findings about differences in innovation strategies and motives of EMNEs and AMNEs are

driven by the home country characteristics of the multinationals and location advantages of

both home and host countries. Can findings from Chinese multinationals be applied to Indian

and other emerging market multinationals? What is the role of the location advantages and

disadvantages of emerging markets (both as home and host countries) in affecting motives for

locating innovation-intensive activities abroad?

Research question: How do location advantages and disadvantages affect innovation

motives of emerging multinationals in emerging markets?

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3714080

Figure 1: A framework for understanding emerging MNEs innovating in emerging markets

Firm-specific

advantages &

disadvantages

Home country Host country

Location Location

advantages & advantages &

disadvantages disadvantages

Motives

for

innovation

abroad

Design/methodology/approach

We use a multiple-case study method, appropriate to study this emerging and poorly

understood phenomenon in international business (Ghauri, 2004). At this stage, we conducted

11 interviews with senior R&D/innovation and subsidiary managers and 5-10 more are

envisaged in 2017.

Data

Our empirical sample consists of five Indian firms, one Brazilian, one South Korean, one

South African and one Polish firm. This will allow us to tease out potential differences

between the international innovation motives of Indian and other non-Chinese emerging

market firms. Within the group of non-Indian firms, we have two firms that invested in

innovation in the Czech Republic (South African and South Korean firms) and two that

invested in innovation in China (Brazilian and Polish firms). With the location of the

innovation constant, we can distinguish between location advantages of the host country and

the location advantages and disadvantages of the home country. Our sample also consists of

firm groups from the same industry, allowing us to analyze industry effects (two of Indian

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3714080

firms are from the pharmaceutical industry, two Indian firms are from the IT services

industry, and three of non-Indian firms are from the machinery manufacturing). In one of our

case companies we were able to triangulate the perspectives by interviewing three managers:

Senior R&D Manager responsible for Europe, R&D Global Product Engineering Director,

and a former R&D Manager from the Brazilian headquarters.

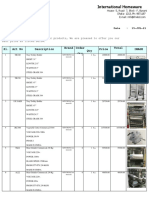

Table 1:

Cases (the ones in bold we were able to analyze, for the others analysis is still under way)

Firm Home Host country Industry Interviewee(s) location

country

1 South Czech FMCGs Netherlands (HQ)

Africa Republic

2 South Korea Czech Machinery Czech Republic (subsidiary)

Republic

3 Poland China Machinery Poland (HQ)

4 Brazil Slovakia, Machinery Slovakia (2), Brazil (HQ)

China

5 India Czech & E-commerce Czech Republic (subsidiary)

Slovak

6 India Lithuania IT services Lithuania (subsidiary)

7 India Russia Pharmaceuticals Russia (subsidiary)

8 India Poland IT services Poland (subsidiary)

9 India Poland Pharmaceuticals Poland (subsidiary)

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3714080

Findings

Our tentative findings from the three cases highlighted in bold offer several insights. First,

two of our cases are large multinationals originating from emerging economies but later

undergone mergers with or acquisitions (of its CEE assets) by developed country

multinationals. We point to the limitations of the ownership classification into advanced and

emerging MNEs and show how the complexity of ownership and ownership changes in large

multinationals affect location decisions about innovation.

On a more granular level, we analyze the dual locations in “advanced” and “emerging”

Europe, as many of our firms have located their innovative subsidiaries in both Western and

Central and Eastern Europe. We explain how CEE members of the European Union such as

Slovakia and Lithuania are attempting to move up the value chain to attract location of R&D

and innovation departments by MNEs. We show that subsidiary initiative often plays a major

role in these decisions and that they are not necessarily made “rationally” at the top level in

the headquarters but with substantial contribution (or predominantly) by subsidiary managers

(Ciabuschi, Forsgren, and Martin, 2011).

We are also in the process of analyzing interview data for the other four cases. We focus on

disentangling the relationships between the nature of the motives for innovation, the impact

of home country characteristics, in particular location advantages and disadvantages of home

countries (India, South Korea and Poland) and host countries (Czech Republic, Slovakia,

Russia, and Poland). To tease out the unique role of home country, we will focus on location

advantages and disadvantages of Brazil vs Poland and South Africa vs South Korea (home

countries) respectively versus location advantages and disadvantages of China and the Czech

Republic (host countries) in innovation.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3714080

The analysis of Indian multinationals innovating in Central and Eastern Europe will allow us

to tease out potential roles of host country location (dis)advantages relative to home country

(dis)advantages in affecting the motives for innovation investment. Host country location

factors may have a larger impact on motives than home country factors (Ingršt, Zámborský,

and Dachs, 2015). We are also analyzing potential commonalities in innovation motives of

multinationals from the same country (India) compared to research on Chinese MNEs

investing in R&D in Europe (Di Minin et al. 2012). One notable difference is that while the

five Chinese cases of investment in R&D in Europe analyzed in Di Minin et al. (2012) were

located in Western Europe, our Indian cases are firms innovating in Central and Eastern

Europe, with possibly unique motivations and locational strategies for that.

Discussion

Subsidiary roles in transition economies are important for our understanding of economic

development and corporate strategies in emerging markets (Giroud, Jindra, and Scott-Kennel,

2009; Uhlenbruck, 2004). We have an increasingly solid awareness of how the roles of

subsidiaries in the MNE network evolve, with many subsidiaries acquiring strategic

independence in core activities such as R&D (Mudambi and Navarra, 2004; Ambos, Ambos

and Schlegelmilch, 2006). We contribute to our understanding of how subsidiary autonomy

and initiative (including capacity to innovate) evolve in the context of regional division of

responsibilities between different subsidiaries in advanced and emerging Europe. We show

how emerging multinationals’ lenses in making strategic decisions about subsidiary roles and

autonomy are often unique, industry dependent and driven by their knowledge about and

evidence of subsidiaries’ innovative capacity.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3714080

Originality/value

While operations of emerging multinationals in emerging markets are increasingly gaining

attention of scholars (Ramamurti and Singh, 2009), motives for investment by emerging

multinationals in R&D and innovation in emerging markets and Central and Eastern Europe

in particular are still under-researched and poorly understood. Our study is one of the first in

this area.

Future research directions

The role of home and host country location advantages and in disadvantages in particular is

important in our understanding of emerging multinationals and their innovation and

locational strategies. Our study focuses on the under-researched non-Chinese investment

emerging multinationals’ investment into innovation in Central and Eastern Europe.

Research limitations/implications

This is a work in progress and the number of (analyzed) cases is arguably small at this stage.

While we have a large proportion of interviewees from CEE, only a couple of interviews are

from headquarters or Western Europe. Having multiple interviewees for more cases would

add to triangulation. In terms of implications for future research, our study encourages more

attention to the intersection of the literature on the characteristics of the home country of

multinationals and innovation locational strategy of emerging multinationals in

emerging/CEE markets. Policy and business leaders from these markets are keen on bringing

more innovative work there, and understanding motives, behaviors and contingencies behind

successful trailblazers of this trend is valuable.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3714080

References

Ambos, T. C., Ambos, B., & Schlegelmilch, B. B. (2006). Learning from foreign

subsidiaries: An empirical investigation of headquarters’ benefits from reverse knowledge

transfers. International Business Review, 15(3): 294– 312.

Ambos, B., & Ambos, T. C., (2011). Meeting the challenge of offshoring R&D: an examination

of firm‐and location‐specific factors. R&D Management, 41(2): 107-119.

Bilkey, W. J., & and Ness, E. (1982). Country-of-origin effects on product evaluations.

Journal of International Business Studies, 13(1): 89-99.

Chung, W., & Alcácer, J. (2002). Knowledge seeking and location choice of foreign direct

investment in the United States. Management Science, 48(12), 1534-1554.

Ciabuschi, F., Forsgren, M., & Martín, O. M. (2011). Rationality vs ignorance: The role of

MNE headquarters in subsidiaries’ innovation processes. Journal of International Business

Studies, 42(7), 958-970.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A., & Genc, M. (2008). Transforming disadvantages into advantages:

Developing country MNEs in the least developed countries. Journal of International Business

Studies, 39(6): 957-979.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A., & Ramamurti, R. (2014). Understanding multinationals from emerging

markets. Cambridge , UK: Cambridge University Press.

Di Minin, A., Zhang, J., & Gammeltoft, P. (2012). Chinese foreign direct investment in R&D

in Europe: A new model of R&D internationalization? European Management Journal, 30(3):

189-203.

Ghauri, P. (2004). Designing and conducting case studies in international business

research. Handbook of qualitative research methods for international business, 109-124.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3714080

Giuliani, E., Gorgoni, S., Günther, C., & Rabellotti, R. (2014). Emerging versus advanced

country MNEs investing in Europe: A typology of subsidiary global–local connections.

International Business Review, 23(4): 680-691.

Ingršt, I., Zámborský, P., and Dachs, B. (2015). International innovation in Europe: Diversity

of origin, location and motives. Paper presented at 29th Australian and New Zealand

Academy of Management Annual Conference, Queenstown, New Zealand. 2 December - 4

December 2015.

Håkanson, L., & Nobel, R. (1993). Determinants of foreign R&D in Swedish multinationals.

Research Policy, 22(5), 397-411.

Jindra, B., Giroud, A. and Scott-Kennel, J. (2009). Subsidiary roles, vertical linkages and

economic development: Lessons from transition economies. Journal of World Business,

44(2): 167-179.

Khanna, T., & Palepu, K. (1997). Why focused strategies may be wrong for emerging markets.

Harvard Business Review, 75(4): 41-51.

Mudambi, R., & Navarra, P. (2004). Is knowledge power? Knowledge flows, subsidiary power

and rent-seeking within MNCs. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(5): 385–404.

Narula, R., (2012). Do we need different frameworks to explain infant MNEs from developing

countries?. Global Strategy Journal, 2(3), pp. 188-204.

Ramamurti, R., & Singh, J. V. (2009). Emerging multinationals in emerging markets.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Uhlenbruck, K. (2004). Developing acquired foreign subsidiaries: The experience of MNEs in

transition economies. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(5): 109–123.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3714080

Verbeke, A. (2013). International business strategy. 2nd edition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Von Zedtwitz, M., & Gassmann, O. (2002). Market versus technology drive in R&D

internationalization: four different patterns of managing research and development. Research

Policy, 31(4): 569-588

Wells, L. T. (1983). Third world multinationals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Zámborský, P., & Jacobs, E. (2016). Reverse productivity spillovers in the OECD: The

contrasting roles of R&D and capital. Global Economy Journal, 16(1), 113-133.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3714080

You might also like

- Business Simulation - 2021Document13 pagesBusiness Simulation - 2021rafiaNo ratings yet

- Influence of Recruitment Retention and MotivationDocument10 pagesInfluence of Recruitment Retention and MotivationarakeelNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Offshoring on the Information Technology Sector: Is It Really Affecting UsFrom EverandThe Effect of Offshoring on the Information Technology Sector: Is It Really Affecting UsNo ratings yet

- A STUDY ON THE ANALYSIS OF FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE OF KUMARI BANK LIMITED - Docx RepotDocument34 pagesA STUDY ON THE ANALYSIS OF FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE OF KUMARI BANK LIMITED - Docx RepotGopal Rimal100% (4)

- Outsourcing: Blessing or A Curse A Comparison of EconomiesDocument8 pagesOutsourcing: Blessing or A Curse A Comparison of EconomiesAllen AlfredNo ratings yet

- Emerging Multinationals in Emerging Markets: Xiaomi Experience in The Indian Smartphone MarketDocument19 pagesEmerging Multinationals in Emerging Markets: Xiaomi Experience in The Indian Smartphone MarketUmair BaigNo ratings yet

- Global R&D Project Management and Organization: A TaxonomyDocument19 pagesGlobal R&D Project Management and Organization: A TaxonomyLuis Filipe Batista AraújoNo ratings yet

- ''HR Outsourcing in India ResearchDocument77 pages''HR Outsourcing in India ResearchSami Zama100% (2)

- Michael Porter Diamond Theory & It's ApplicationDocument18 pagesMichael Porter Diamond Theory & It's ApplicationAbhishek PandeyNo ratings yet

- Food Forests in A Temperate Climate - Anastasia Limareva PDFDocument123 pagesFood Forests in A Temperate Climate - Anastasia Limareva PDFValentina Angelini100% (1)

- MBA Research ProposalDocument8 pagesMBA Research Proposalaku01198788% (8)

- 2012 RKTDocument15 pages2012 RKThugotolomeiNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Ownership Identity On Corporate Diversification Strategy of Chinese Companies in Foreign MarketsDocument44 pagesThe Effects of Ownership Identity On Corporate Diversification Strategy of Chinese Companies in Foreign MarketsCLABERT VALENTIN AGUILAR ALEJONo ratings yet

- 1 Adv and Disadv of Multinaitonal CompaniesDocument4 pages1 Adv and Disadv of Multinaitonal CompaniesimranNo ratings yet

- EM 19-14 InternationalizationDocument20 pagesEM 19-14 InternationalizationMikkel GramNo ratings yet

- DiamondDocument12 pagesDiamondSoumya Barman100% (2)

- Growth of KPODocument11 pagesGrowth of KPOsabyavgsomNo ratings yet

- Monopolistic Advantage TheoryDocument8 pagesMonopolistic Advantage TheoryKaveneNo ratings yet

- Suman ChoudharyDocument6 pagesSuman ChoudharyHUMNANo ratings yet

- Key Elements For The Future Of: Technology Sourcing in The Peruvian Industry: A Prospective StudyDocument13 pagesKey Elements For The Future Of: Technology Sourcing in The Peruvian Industry: A Prospective StudychcenzanoNo ratings yet

- Mba Master Thesis PDFDocument4 pagesMba Master Thesis PDFsarareedannarbor100% (2)

- International Journal of Management (Ijm) : ©iaemeDocument5 pagesInternational Journal of Management (Ijm) : ©iaemeIAEME PublicationNo ratings yet

- IBUS 321 Forum Q and ADocument3 pagesIBUS 321 Forum Q and Amarina belmonte100% (1)

- Godana Assignment Article 6Document13 pagesGodana Assignment Article 6Godana HukaNo ratings yet

- MPRA Paper 33076Document59 pagesMPRA Paper 33076dfsdjgflksjgnawNo ratings yet

- Theories of ManagementDocument10 pagesTheories of ManagementAurelio Espinoza AbalosNo ratings yet

- Analysis of India S National Competitive Advantage in ITDocument40 pagesAnalysis of India S National Competitive Advantage in ITkapildixit30No ratings yet

- Day 1 S3 MaffioliDocument22 pagesDay 1 S3 MaffioliDetteDeCastroNo ratings yet

- Market Potential ThesisDocument7 pagesMarket Potential Thesisfbzgmpm3100% (2)

- International Organization Strategy - Keyvan SimetgoDocument14 pagesInternational Organization Strategy - Keyvan SimetgoDr. Keivan simetgo100% (1)

- Crescenzi Dyevre Neffke Paper 7 Innovation Catalysts 2020Document38 pagesCrescenzi Dyevre Neffke Paper 7 Innovation Catalysts 2020Lory DuartNo ratings yet

- Marvin IQPDocument41 pagesMarvin IQPRenn BuycoNo ratings yet

- Dtac 006Document20 pagesDtac 006amirhayat15No ratings yet

- GBS Mid Term (19-91239-1) PDFDocument9 pagesGBS Mid Term (19-91239-1) PDFMd RakibNo ratings yet

- Lezione 1 Multinational Corporation (MNC) Basic DefinitionDocument9 pagesLezione 1 Multinational Corporation (MNC) Basic DefinitionControsenso Acoustic DuoNo ratings yet

- Competitive Intelligence and International BusinessDocument7 pagesCompetitive Intelligence and International BusinessKenjin SaiNo ratings yet

- A Model For Offshore Information Systems Outsourcing Provider Selection in Developing CountriesDocument10 pagesA Model For Offshore Information Systems Outsourcing Provider Selection in Developing CountriesericNo ratings yet

- GE ChinaDocument6 pagesGE ChinajuliedehaesNo ratings yet

- 02 International Strategic PlanningDocument11 pages02 International Strategic PlanningTine MontaronNo ratings yet

- Tax AvoidanceDocument19 pagesTax AvoidanceANGGI REFTIANANo ratings yet

- Tata Elxsi Mini ProjectDocument46 pagesTata Elxsi Mini Projectramkiran100% (1)

- Ib Assignment FinalDocument7 pagesIb Assignment FinalGaurav MandalNo ratings yet

- TATA and SailDocument61 pagesTATA and SailSarika SurveNo ratings yet

- Determinants of FDI in CambodiaDocument34 pagesDeterminants of FDI in CambodiaThach BunroeunNo ratings yet

- IT Sector and RecessionDocument16 pagesIT Sector and Recessionakshay.madhavNo ratings yet

- International Business Strategy ModelDocument7 pagesInternational Business Strategy Modelgracecarr83No ratings yet

- EM 19-19 Location ChoiceDocument25 pagesEM 19-19 Location ChoiceMikkel GramNo ratings yet

- Advantages and Disadvantages of FDI in China and India: International Business Research April 2012Document12 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of FDI in China and India: International Business Research April 2012muj_aliNo ratings yet

- BCG and 5 Force Analysis of Infosys, Wipro, Tech MahindraDocument8 pagesBCG and 5 Force Analysis of Infosys, Wipro, Tech MahindraAnu Prakash100% (3)

- The Pros and Cons of Offshoring - Literature ReviewDocument11 pagesThe Pros and Cons of Offshoring - Literature ReviewMaine GaIvezNo ratings yet

- 1capstone ReportDocument7 pages1capstone ReportAninda MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Disruptive Innovations PDFDocument10 pagesDisruptive Innovations PDFAntonio Mayoral ChavandoNo ratings yet

- Effects of Entry Strategies On The Strategic Performance of Equity BankDocument17 pagesEffects of Entry Strategies On The Strategic Performance of Equity BankEhsan DarwishmoqaddamNo ratings yet

- IHRM FullDocument29 pagesIHRM Fulltrendy FashionNo ratings yet

- SWOT ND Pest... SleptDocument4 pagesSWOT ND Pest... Sleptsunnychowdhri90No ratings yet

- Dsir StudiesDocument3 pagesDsir StudieskirupasrimathNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id305345Document25 pagesSSRN Id305345Axay ZxzyNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Global It InnovationDocument5 pagesRunning Head: Global It InnovationExpert TutoraNo ratings yet

- National DiamondDocument7 pagesNational DiamondAditya MehraNo ratings yet

- Differences in Outsourcing Strategies Between Firms in Emerging and in Developed MarketsDocument26 pagesDifferences in Outsourcing Strategies Between Firms in Emerging and in Developed Marketsnaga25frenchNo ratings yet

- Framework Author: Michael E. Porter Year of Origin: Originating Organization: The Competitive Advantage of Nations Book Objective (Edit by Souvik)Document13 pagesFramework Author: Michael E. Porter Year of Origin: Originating Organization: The Competitive Advantage of Nations Book Objective (Edit by Souvik)KAPIL MBA 2021-23 (Delhi)No ratings yet

- Drug Addiction EssayDocument9 pagesDrug Addiction Essayafabilalf100% (2)

- Management Enquiry and Research Methods: Student Name: Tirupathi Rao.mDocument10 pagesManagement Enquiry and Research Methods: Student Name: Tirupathi Rao.mMudit DubeyNo ratings yet

- Georgia’s Emerging Ecosystem for Technology StartupsFrom EverandGeorgia’s Emerging Ecosystem for Technology StartupsNo ratings yet

- Journal of System and Management SciencesDocument6 pagesJournal of System and Management SciencesShaikh Fazlur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Staauh 19Document14 pagesStaauh 19Shaikh Fazlur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Main File For Peer Review aRTICLE sAMPLEDocument17 pagesMain File For Peer Review aRTICLE sAMPLEShaikh Fazlur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Ielts - Writing - Lect - 04Document19 pagesIelts - Writing - Lect - 04Shaikh Fazlur RahmanNo ratings yet

- International Homeware: Hotel FarmgateDocument3 pagesInternational Homeware: Hotel FarmgateShaikh Fazlur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Banglalink Corporate Proposal For FAITH GROUPDocument13 pagesBanglalink Corporate Proposal For FAITH GROUPShaikh Fazlur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Letter of AcceptanceDocument1 pageLetter of AcceptanceShaikh Fazlur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Profile of Supplies LTD 2021 To 2022Document12 pagesProfile of Supplies LTD 2021 To 2022Shaikh Fazlur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Thesis 1111525 Evgenia AntonovaDocument101 pagesThesis 1111525 Evgenia AntonovaOprea AlinaNo ratings yet

- Paper On Locus of ControlDocument13 pagesPaper On Locus of ControlSunil Sadhwani100% (1)

- Jurnal Internasional EkowisataDocument23 pagesJurnal Internasional EkowisataXXX PegasuSNo ratings yet

- Paper Airplane Science Fair Project ResearchDocument4 pagesPaper Airplane Science Fair Project Researchyhclzxwgf100% (1)

- Pointing To Shaun Tan's Re-Imagining Visual Poetics in ResearchDocument17 pagesPointing To Shaun Tan's Re-Imagining Visual Poetics in ResearchGhost hackerNo ratings yet

- A Proposed Structure For A Website Content-Based System For Students' Research Paper of Mapúa University A Comprehensive AnalysisDocument172 pagesA Proposed Structure For A Website Content-Based System For Students' Research Paper of Mapúa University A Comprehensive AnalysisRamil Joshua TrabadoNo ratings yet

- Exploring The Food and Cultural Significance of Native Chicken in Ilocos SurDocument7 pagesExploring The Food and Cultural Significance of Native Chicken in Ilocos SurAlbert CalingNo ratings yet

- Implementasi Kebijakan Pencegahan Pemberantasan Penyalahgunaan Dan Peredaran Gelap Narkoba (P4Gn) Pada Bidang Rehabilitasi Badan Narkotika Nasional Kota SurabayaDocument11 pagesImplementasi Kebijakan Pencegahan Pemberantasan Penyalahgunaan Dan Peredaran Gelap Narkoba (P4Gn) Pada Bidang Rehabilitasi Badan Narkotika Nasional Kota SurabayaVida DeknongNo ratings yet

- Checklist en TU BerlinDocument2 pagesChecklist en TU BerlinWilhelm WinsorNo ratings yet

- Dobson and Sloboda - Staying Behind - 25 10 12Document22 pagesDobson and Sloboda - Staying Behind - 25 10 12John SlobodaNo ratings yet

- 欢迎来到电子论文和论文数据库Document5 pages欢迎来到电子论文和论文数据库qewqtxfng100% (1)

- BSC Psychology Dissertation TopicsDocument5 pagesBSC Psychology Dissertation TopicsBuyThesisPaperCanada100% (1)

- Wai ChungDocument29 pagesWai ChungaraneyaNo ratings yet

- Hejje Jan 2011 (Book)Document52 pagesHejje Jan 2011 (Book)Socialwork Karnataka NiratankaNo ratings yet

- Significance of The StudyDocument2 pagesSignificance of The StudykmarisseeNo ratings yet

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument27 pagesReview of Related LiteratureRodel RomeroNo ratings yet

- Chapter1 Introd QRDocument22 pagesChapter1 Introd QRrajanityagi23No ratings yet

- Cultural Perspectives On Communication in Community LeadershipDocument160 pagesCultural Perspectives On Communication in Community LeadershipzarinaadenaNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of The Control Environment Practices of Private Catholic Schools: Towards Crafting of A Comprehensive Operations Management SystemDocument8 pagesAn Analysis of The Control Environment Practices of Private Catholic Schools: Towards Crafting of A Comprehensive Operations Management SystemPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Thesis Online BankingDocument8 pagesThesis Online Bankingafktmcyddtthol100% (2)

- Leadership in Enabling and Industrial TechnologiesDocument117 pagesLeadership in Enabling and Industrial TechnologiesHosea HandoyoNo ratings yet

- Nelson College London: Student Name: Student ID: Unit/Module: ProgrammeDocument23 pagesNelson College London: Student Name: Student ID: Unit/Module: ProgrammeTafheemNo ratings yet

- Blockchain 4 Open Science & SDGSDocument8 pagesBlockchain 4 Open Science & SDGSsywar ayachiNo ratings yet

- Evaluation On The Implementation of The Marketing Trade Subject Curriculum in Anambra State.Document70 pagesEvaluation On The Implementation of The Marketing Trade Subject Curriculum in Anambra State.FraNKAPPNo ratings yet

- 6.4.1 Institutional Strategies For Mobilization of Funds and The Optimal Utilization of ResourcesDocument10 pages6.4.1 Institutional Strategies For Mobilization of Funds and The Optimal Utilization of ResourcesiyalazhaguNo ratings yet

- Janet P. Espada Et Al., Challenges in The Implementation of The Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education Program:A Case StudyDocument19 pagesJanet P. Espada Et Al., Challenges in The Implementation of The Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education Program:A Case StudyAnalyn Bintoso DabanNo ratings yet