Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Investment and Saving in Globalized Financial Markets

Uploaded by

ethanwuu03Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Investment and Saving in Globalized Financial Markets

Uploaded by

ethanwuu03Copyright:

Available Formats

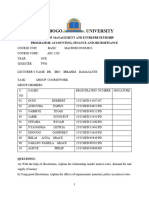

26_raga_ch26_topic_01.

qxd 23/2/10 4:31 pm Page 1

I N V E S T M E N T A N D S AV I N G I N G L O B A L I Z E D F I N A N C I A L M A R K E T S 1

Investment and Saving in Globalized

Financial Markets

In Chapter 15 in Microeconomics and Chapter 26 in Macroeconomics we examine

how the real interest rate is determined in the market for financial capital by the inter-

action of the supply of saving and the demand for investment. In both chapters we are

examining a closed economy—that is, an economy that trades neither goods nor finan-

cial assets with the rest of the world. Our closed-economy model predicts that a change

in Canada’s investment demand or Canada’s supply of national saving leads to a

change in Canada’s equilibrium interest rate, even if the interest rates in other countries

are held constant.

In reality, however, there is a great deal of international trade in financial assets.

Every day, households, firms, and governments in one country purchase assets from

(and sell assets to) households, firms, and governments in other countries. Billions of

dollars worth of financial assets cross international borders all the time. One result of

these massive financial flows is that interest rates on similar assets in different countries

tend to move together. For example, when interest rates on ten-year Canadian govern-

ment bonds rise by one percentage point, similar changes usually occur to the interest

rates on ten-year U.S. government bonds, and also on ten-year German, Japanese, and

Australian government bonds.

With globalized financial markets, in other words, our closed-economy model

presented in Chapters 15 and 26 does not provide a complete description of what is

happening. Here we develop a version of the model better suited to an economy in

which financial assets flow easily across international boundaries.

The Law of One Price in a Globalized Financial Market

We begin with the closed-economy model from Chapters 15 and 26, which can be

summarized with the following three key assumptions:

1. The quantity of financial capital demanded is negatively related to the real interest

rate.

2. The quantity of saving supplied (“national saving”) is positively related to the real

interest rate.

3. There is a single type of financial capital in the country, and hence we can think of

a single interest rate as its price.

The third assumption is necessary in order to speak of a single market for financial

capital, and thus a single price for that product—the interest rate. If there were many

types of financial assets, varying in their riskiness or in their term to maturity, then we

would have to think separately about the market for each asset, and there would be

several interest rates to determine. In reality, there are many types of financial asset.

This third assumption is therefore a simplifying one that allows us to focus on the

determination of interest rates in general, while ignoring movements between the dif-

ferent interest rates that apply to different types of assets.

With these three central assumptions, our model predicts that the equilibrium real

interest rate in Canada will be determined at the intersection of the downward-sloping

Ragan, Economics, 14th Canadian Edition

Copyright © 2014 Pearson Canada Inc.

26_raga_ch26_topic_01.qxd 23/2/10 4:31 pm Page 2

2 I N V E S T M E N T A N D S AV I N G I N G L O B A L I Z E D F I N A N C I A L M A R K E T S

investment demand curve and the upward-sloping supply curve for national saving. Like

other demand-and-supply models, we assume that the interest rate will adjust upward

or downward until this equilibrium interest rate is reached. In addition, any shifts in

the two curves will lead to changes in the equilibrium interest rate and to changes in

the equilibrium flow of investment and saving.

We now modify this closed-economy model with two further assumptions:

4. Financial capital is highly mobile and can be freely traded internationally.

5. There is a single type of financial capital in the world.

Assumption 4 makes this an open-economy rather than a closed-economy model;

assumption 5 extends assumption 3 to the whole world, whereby we assume that all

financial assets, both inside and outside of Canada, are the same.

Assumptions 4 and 5, taken together, lead to the prediction that there will be a

single interest rate in the world market for financial capital. Since all financial assets

are the same, and since they can be freely traded across international boundaries, it is

not possible to have different interest rates in different countries. If there were different

interest rates in different countries, lenders would quickly shift their supply of financial

capital to the countries with higher interest rates, and this increase in supply would

tend to push down the interest rate in these countries. At the same time, borrowers

would quickly shift their demand to countries with lower interest rates, and this

increase in demand would tend to raise the interest rate in these countries. If financial

capital is very mobile across borders, the immediate result of these shifts would be to

bring interest rates in different countries to the same level. This result is an application

of the law of one price.

Figure 1 illustrates saving, investment, and interest rates in this model of a globalized

financial market. Part (i) of the figure shows the world market for financial capital,

with the world investment demand curve (ID) and the world supply of saving curve (S).

Each of these curves is the horizontal summation of the demand (or supply) curves

from the many individual countries. The world equilibrium interest rate (iW) is deter-

mined at the intersection of the world investment demand and world saving supply

curves.

FIGURE 1 The World and Canadian Markets for Financial Capital

S SCan

Real Interest Rate

Real Interest Rate

Excess supply

}

i*W i*W

ID IDCan

QW Quantity of qI qS Quantity of

Financial Capital Financial Capital

(i) World (ii) Canada

Ragan, Economics, 14th Canadian Edition

Copyright © 2014 Pearson Canada Inc.

26_raga_ch26_topic_01.qxd 3/25/10 5:50 PM Page 3

I N V E S T M E N T A N D S AV I N G I N G L O B A L I Z E D F I N A N C I A L M A R K E T S 3

Part (ii) of the figure shows the Canadian market for financial capital with the

Canadian investment demand curve and the Canadian saving supply curve. Given the

law of one price applied to the world market for financial assets, the interest rate in

Canada must be the same as the world equilibrium interest rate determined in part (i),

for any amounts of investment demanded or saving supplied in Canada. Thus, it is not

necessarily true that the quantity of investment demanded will equal the quantity of

saving supplied in Canada. Part (ii) is drawn in such a way that at the world equilib-

rium interest rate, the quantity of saving supplied in Canada, qS, exceeds the quantity

of investment demanded, qI.The idea that saving and investment need not be equated

within an individual country raises the obvious question: What happens if there is a

gap between the two?

Investment–Saving Imbalances Within a Country

Figure 2 shows the market for financial capital in Canada for a given level of the equi-

librium world interest rate. We consider alternative positions of the investment demand

and saving supply curves in Canada. In part (i), there is an excess supply of financial

capital in Canada at the equilibrium world interest rate. In part (ii), there is an excess

demand for financial capital in Canada at the equilibrium world interest rate. In both

cases, note that the imbalance between the quantity of investment demanded and the

quantity of saving supplied in Canada creates no pressure for the world interest rate to

change. The world interest rate is determined in the equilibrium of the world financial

market, in a situation like part (i) of Figure 1, where the total quantity of investment

demanded equals the total quantity of saving supplied. But even when the world finan-

cial market is in equilibrium, many individual countries will have situations like part (i)

in Figure 2, and many others will have situations like part (ii). In fact, when the world

financial market is clearing, the sum of all the excess supplies, as in part (i), will exactly

equal the sum of all the excess demands, as in part (ii).

Now consider parts (i) and (ii) of Figure 2 separately. If Canada has an excess

supply of financial capital at the equilibrium world interest rate, as in part (i), where

does Canada’s “extra” saving go? Canada’s national saving is more than sufficient to

FIGURE 2 Investment–Saving Imbalances

S1 S2

Real Interest Rate

Real Interest Rate

Capital outflow

}

iW iW

}

Capital inflow

I2D

I1D

Quantity of Quantity of

Financial Capital Financial Capital

(i) Capital outflow = current account surplus (ii) Capital inflow = current account deficit

Ragan, Economics, 14th Canadian Edition

Copyright © 2014 Pearson Canada Inc.

26_raga_ch26_topic_01.qxd 23/2/10 4:31 pm Page 4

4 I N V E S T M E N T A N D S AV I N G I N G L O B A L I Z E D F I N A N C I A L M A R K E T S

finance all of the investment desired by Canadian firms. The extra saving can then be used

to acquire foreign assets.1 Canada as a whole has a capital outflow because Canadian

financial capital is flowing abroad to purchase those assets. In terms of the balance-of-

payments accounting that is discussed in Chapter 35, Canada in this case has a current

account surplus.

Now consider part (ii) of Figure 2. If Canada has an excess demand for financial

capital at the equilibrium world interest rate, how does Canada finance all of its desired

investment? Canada’s national saving is insufficient to finance all of the investment

desired by Canadian firms, and so some additional financing must be provided by for-

eigners. This is accomplished by Canadians selling assets to foreigners. Canada has a

capital inflow because foreign financial capital flows into Canada in order to purchase

Canadian assets. In terms of the balance-of-payments accounting discussed in Chapter 35,

Canada in this case has a current account deficit.

Domestic Shocks

We can now imagine what would happen in Canada’s financial market if there were a

shift either in Canada’s investment demand curve or in Canada’s saving supply curve. If

there is no change in the world investment demand and saving supply curves, there will

be no change in the equilibrium world interest rate. Thus, any shift in the demand or

supply curves in Canada will simply change the amount of excess supply or excess

demand of financial capital. Canada’s current account deficit or surplus will change,

but there will be no change in the equilibrium interest rate. An increase in the supply of

saving (with investment demand held constant) will lead to a greater flow of Canadian

saving and thus to an increase in Canada’s current account surplus (or a reduction in

the current account deficit). Conversely, an increase in investment demand (with the

supply of saving held constant) will lead to a greater flow of Canadian investment and

thus to an increase in Canada’s current account deficit (or a reduction in the current

account surplus).

1 In this simple model, Canadians would purchase from foreigners the one type of asset that exists. In reality,

an excess of saving over investment in Canada would lead to the accumulation of many kinds of foreign

assets—stocks, bonds, physical capital, and land.

Ragan, Economics, 14th Canadian Edition

Copyright © 2014 Pearson Canada Inc.

You might also like

- Summary of Anthony Crescenzi's The Strategic Bond Investor, Third EditionFrom EverandSummary of Anthony Crescenzi's The Strategic Bond Investor, Third EditionNo ratings yet

- The Mundell-Fleming Model With Partial International Capital MobilityDocument22 pagesThe Mundell-Fleming Model With Partial International Capital MobilityHenok FikaduNo ratings yet

- MundellDocument12 pagesMundellGisell Camila Cardona GNo ratings yet

- Assignment of IfDocument7 pagesAssignment of IfAnand SinghNo ratings yet

- Summary of David A. Moss's A Concise Guide to Macroeconomics, Second EditionFrom EverandSummary of David A. Moss's A Concise Guide to Macroeconomics, Second EditionNo ratings yet

- IRPDocument22 pagesIRPankur018No ratings yet

- Dollarization: Carlos A. Végh University of Maryland and NBER Version: July 6, 2011Document75 pagesDollarization: Carlos A. Végh University of Maryland and NBER Version: July 6, 2011Martin ArrutiNo ratings yet

- Reference:: Mishkin, Frederic S., The 10th Edition, Pearson Addison WesleyDocument46 pagesReference:: Mishkin, Frederic S., The 10th Edition, Pearson Addison WesleyNDNo ratings yet

- Taylor SubprimeDocument25 pagesTaylor SubprimeppphhwNo ratings yet

- Group 3 Money Banking and Monetary PolicyDocument46 pagesGroup 3 Money Banking and Monetary PolicyjustinedeguzmanNo ratings yet

- Exchange Rate TheoriesDocument21 pagesExchange Rate Theoriesalekya.nyalapelli03No ratings yet

- 0pooja NawleDocument36 pages0pooja NawleNandini JaganNo ratings yet

- ms45 Dec 6Document9 pagesms45 Dec 6sudhir.kochhar3530No ratings yet

- Brief Principles of Macroeconomics 7Th Edition Gregory Mankiw Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument36 pagesBrief Principles of Macroeconomics 7Th Edition Gregory Mankiw Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFlois.guzman538100% (11)

- Session 6 - Money Market EquilibriumDocument8 pagesSession 6 - Money Market EquilibriumNikhil kumarNo ratings yet

- 105-Notes Money Demand - Interest Rates-And PolicyDocument14 pages105-Notes Money Demand - Interest Rates-And PolicyBảo Vy TrươngNo ratings yet

- Exchange Rate and BOP Exam QuestionsDocument8 pagesExchange Rate and BOP Exam QuestionsGABRIELLA GUNAWANNo ratings yet

- What Drives Long-Term Capital Flows? A Theoretical and Empirical InvestigationDocument37 pagesWhat Drives Long-Term Capital Flows? A Theoretical and Empirical InvestigationMartha MagallanesNo ratings yet

- Financing Government Through Monetary Expansion and InflationDocument9 pagesFinancing Government Through Monetary Expansion and InflationflowerboyNo ratings yet

- Feldstein 1980Document17 pagesFeldstein 1980Marie Laure BelomoNo ratings yet

- C15 Krugman 12e Accessible EdDocument48 pagesC15 Krugman 12e Accessible Ed7ARDELIA GRANDIVA CIPTAMURTINo ratings yet

- RESUMENES Keynes y La Creación Del DineroDocument14 pagesRESUMENES Keynes y La Creación Del DineroJavi TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Chap 4 EnglishDocument17 pagesChap 4 Englishdaniellewadjie1No ratings yet

- Business PCL I Fin Session 9&10 Techniques of HedgingDocument13 pagesBusiness PCL I Fin Session 9&10 Techniques of HedgingAashima JainNo ratings yet

- Reading Lesson 6Document8 pagesReading Lesson 6AnshumanNo ratings yet

- MONEY MARKET Project - McomDocument50 pagesMONEY MARKET Project - McomRavi Sahani100% (1)

- Lim Yew Joon B19080668 FMI Tutorial 5Document4 pagesLim Yew Joon B19080668 FMI Tutorial 5Jing HangNo ratings yet

- A Century of Current Account DynamicsDocument24 pagesA Century of Current Account DynamicsZhang PeilinNo ratings yet

- Money Demand (1) - 1Document9 pagesMoney Demand (1) - 1kritikachhapoliaNo ratings yet

- Slide 7Document23 pagesSlide 7Shruti PaulNo ratings yet

- Interest Rate Parity: by - Alpana Kaushal Deepak Verma Seshank Sarin Mba (Ib)Document14 pagesInterest Rate Parity: by - Alpana Kaushal Deepak Verma Seshank Sarin Mba (Ib)Deepak SharmaNo ratings yet

- Exchange Rate DeterminationDocument5 pagesExchange Rate DeterminationSakshi LodhaNo ratings yet

- Olivier de La Grandville-Bond Pricing and Portfolio Analysis-The MIT Press (2000)Document473 pagesOlivier de La Grandville-Bond Pricing and Portfolio Analysis-The MIT Press (2000)João Henrique Reis MenegottoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 (Unit 1)Document21 pagesChapter 3 (Unit 1)GiriNo ratings yet

- International Business FinanceDocument152 pagesInternational Business FinanceTAYO AYODEJI AROWOSEGBENo ratings yet

- Market Equilibrium NotesDocument5 pagesMarket Equilibrium NotesAbel BejaNo ratings yet

- Macro Economics 05 - Daily Class Notes - Mission JRF June 2024 - EconomicsDocument27 pagesMacro Economics 05 - Daily Class Notes - Mission JRF June 2024 - Economicskg704939No ratings yet

- Int Eco II AssignmentDocument7 pagesInt Eco II AssignmentMosisa ShelemaNo ratings yet

- Wtpfrankel cp19 p353-390 PDFDocument38 pagesWtpfrankel cp19 p353-390 PDFitalos1977No ratings yet

- The Search For Stability in An Integrated Global Financial SystemDocument10 pagesThe Search For Stability in An Integrated Global Financial SystemGhazali IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Purchasing Power ParityDocument5 pagesPurchasing Power ParityRahul Kumar AwadeNo ratings yet

- International Finance: Team MembersDocument11 pagesInternational Finance: Team MembersMohanNo ratings yet

- Chap 29Document18 pagesChap 29Syed HamdanNo ratings yet

- 10a - Raj Kamlesh MehtaDocument15 pages10a - Raj Kamlesh MehtaRaj MehtaNo ratings yet

- AEC 501 Question BankDocument15 pagesAEC 501 Question BankAnanda PreethiNo ratings yet

- Penjelasan Tentang Saving-Investment GapDocument40 pagesPenjelasan Tentang Saving-Investment GapbahrulNo ratings yet

- Street. DocsDocument23 pagesStreet. DocsOtim IvanNo ratings yet

- Inistitution 3Document28 pagesInistitution 3Hosnii QamarNo ratings yet

- An Alternative Bond Relative Value Measure: Determining A Fair Value of The Swap Spread Using Libor and GC Repo RatesDocument6 pagesAn Alternative Bond Relative Value Measure: Determining A Fair Value of The Swap Spread Using Libor and GC Repo RatesPayal ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Portfolio BalanceDocument43 pagesPortfolio BalanceBeyond TutoringNo ratings yet

- Forex Bop NcertDocument22 pagesForex Bop NcertananyaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 5 - Interest Rate - MBAIB5214 PDFDocument9 pagesLecture 5 - Interest Rate - MBAIB5214 PDFAsiri GunarathnaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 25Document7 pagesChapter 25Tasnim SghairNo ratings yet

- Unit5 MoneyDocument34 pagesUnit5 Moneytempacc9322No ratings yet

- Ecological Economics-Principles and Applications-8Document50 pagesEcological Economics-Principles and Applications-8Edwin JoyoNo ratings yet

- Review - "FX Markets' Reactions To COVID-19 - Are They Different - "Document5 pagesReview - "FX Markets' Reactions To COVID-19 - Are They Different - "Ecopreneur, Advitya 22'No ratings yet

- Fischer BLACK: Grachtnte School of Business, Uuiccrsity of Chicago, Chicago, III. 60637, U.S.ADocument16 pagesFischer BLACK: Grachtnte School of Business, Uuiccrsity of Chicago, Chicago, III. 60637, U.S.AAndreas KarasNo ratings yet

- Foreign Direct and Portfolio Investments in The WorldDocument31 pagesForeign Direct and Portfolio Investments in The WorldVivek KumarNo ratings yet

- Chain Roop Bansali ScamDocument3 pagesChain Roop Bansali Scamsumit0690100% (1)

- Presentation TDSDocument15 pagesPresentation TDSSHIKHA DWIVEDINo ratings yet

- Sem I Acc - NEP-UGCF 2022Document8 pagesSem I Acc - NEP-UGCF 2022Raj AbhishekNo ratings yet

- Formatted Accounting Finance For Bankers AFB 2 1 PDFDocument6 pagesFormatted Accounting Finance For Bankers AFB 2 1 PDFSijuNo ratings yet

- Application Form 2018Document2 pagesApplication Form 2018Mohammad Arafat YusophNo ratings yet

- Anti-Money Laundering Disclosures and Banks' PerformanceDocument14 pagesAnti-Money Laundering Disclosures and Banks' PerformanceLondonNo ratings yet

- Mirae Asset Equity Allocator Fund of FundDocument26 pagesMirae Asset Equity Allocator Fund of FundAdityaNarayanSinghNo ratings yet

- United States v. Smith, 1st Cir. (1995)Document67 pagesUnited States v. Smith, 1st Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Mark Scheme (Results) Summer 2007: GCE Accounting (6001) Paper 1Document18 pagesMark Scheme (Results) Summer 2007: GCE Accounting (6001) Paper 1Stephanie UCmanNo ratings yet

- T MobileDocument1 pageT MobileMelissa AnneNo ratings yet

- Balance Is OverstatedDocument13 pagesBalance Is Overstatedralph ravasNo ratings yet

- The Sagicor Sigma Global Funds Salary Deduction FormDocument1 pageThe Sagicor Sigma Global Funds Salary Deduction FormRobyn MacNo ratings yet

- Bar Questions - Obligations and ContractsDocument6 pagesBar Questions - Obligations and ContractsPriscilla Dawn100% (9)

- International BankingDocument43 pagesInternational Bankingngochailuong7274No ratings yet

- Your Kotak Corporate Credit Card Statement: Account SummaryDocument2 pagesYour Kotak Corporate Credit Card Statement: Account SummaryManikantaNo ratings yet

- Working Capital NikunjDocument82 pagesWorking Capital Nikunjpatoliyanikunj002No ratings yet

- Taxation Law Bar Exam Questions 2011 AnswersDocument14 pagesTaxation Law Bar Exam Questions 2011 AnswersYochabel Eureca BorjeNo ratings yet

- Amarpali NoticeDocument4 pagesAmarpali NoticeSharjeel AhmadNo ratings yet

- Project PDFDocument92 pagesProject PDFUrvashi SharmaNo ratings yet

- Part A-GEN: (See Instructions) (See Instructions)Document22 pagesPart A-GEN: (See Instructions) (See Instructions)Syed Faisal AhsanNo ratings yet

- Legaspi v. Minister of FinanceDocument2 pagesLegaspi v. Minister of FinanceseanNo ratings yet

- Small Business Bibliography PDFDocument56 pagesSmall Business Bibliography PDFOlaru LorenaNo ratings yet

- Student Coin WhitepaperDocument28 pagesStudent Coin WhitepaperBorsa SırlarıNo ratings yet

- The Wall Street Journal Complete Estate Planning Guidebook by Rachel Emma Silverman - ExcerptDocument32 pagesThe Wall Street Journal Complete Estate Planning Guidebook by Rachel Emma Silverman - ExcerptCrown Publishing Group33% (3)

- Aml Case StdyDocument5 pagesAml Case Stdyammi25100% (2)

- IrfmDocument2 pagesIrfmSuresh Kumar SainiNo ratings yet

- Chapter-1: Submitted By: Bipin SahooDocument48 pagesChapter-1: Submitted By: Bipin SahooAshis Sahoo100% (1)

- Ppe 2016Document40 pagesPpe 2016Benny Wee0% (1)

- Investing in Resilience: Ensuring A Disaster-Resistant FutureDocument188 pagesInvesting in Resilience: Ensuring A Disaster-Resistant FutureAsian Development BankNo ratings yet

- LAW 20013 Law On Obligations and Contracts Midterm ReviewDocument14 pagesLAW 20013 Law On Obligations and Contracts Midterm ReviewNila Francia100% (1)

- A History of the United States in Five Crashes: Stock Market Meltdowns That Defined a NationFrom EverandA History of the United States in Five Crashes: Stock Market Meltdowns That Defined a NationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (11)

- Look Again: The Power of Noticing What Was Always ThereFrom EverandLook Again: The Power of Noticing What Was Always ThereRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- The Meth Lunches: Food and Longing in an American CityFrom EverandThe Meth Lunches: Food and Longing in an American CityRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- Anarchy, State, and Utopia: Second EditionFrom EverandAnarchy, State, and Utopia: Second EditionRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (180)

- University of Berkshire Hathaway: 30 Years of Lessons Learned from Warren Buffett & Charlie Munger at the Annual Shareholders MeetingFrom EverandUniversity of Berkshire Hathaway: 30 Years of Lessons Learned from Warren Buffett & Charlie Munger at the Annual Shareholders MeetingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (97)

- The War Below: Lithium, Copper, and the Global Battle to Power Our LivesFrom EverandThe War Below: Lithium, Copper, and the Global Battle to Power Our LivesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- Financial Literacy for All: Disrupting Struggle, Advancing Financial Freedom, and Building a New American Middle ClassFrom EverandFinancial Literacy for All: Disrupting Struggle, Advancing Financial Freedom, and Building a New American Middle ClassNo ratings yet

- The Infinite Machine: How an Army of Crypto-Hackers Is Building the Next Internet with EthereumFrom EverandThe Infinite Machine: How an Army of Crypto-Hackers Is Building the Next Internet with EthereumRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (12)

- The Trillion-Dollar Conspiracy: How the New World Order, Man-Made Diseases, and Zombie Banks Are Destroying AmericaFrom EverandThe Trillion-Dollar Conspiracy: How the New World Order, Man-Made Diseases, and Zombie Banks Are Destroying AmericaNo ratings yet

- Economics 101: How the World WorksFrom EverandEconomics 101: How the World WorksRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (34)

- Principles for Dealing with the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed or FailFrom EverandPrinciples for Dealing with the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed or FailRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (237)

- The Myth of the Rational Market: A History of Risk, Reward, and Delusion on Wall StreetFrom EverandThe Myth of the Rational Market: A History of Risk, Reward, and Delusion on Wall StreetNo ratings yet

- Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic EventsFrom EverandNarrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic EventsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (94)

- This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The ClimateFrom EverandThis Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The ClimateRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (349)

- Chip War: The Quest to Dominate the World's Most Critical TechnologyFrom EverandChip War: The Quest to Dominate the World's Most Critical TechnologyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (228)

- Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century EconomistFrom EverandDoughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century EconomistRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (37)

- AP Microeconomics/Macroeconomics Premium, 2024: 4 Practice Tests + Comprehensive Review + Online PracticeFrom EverandAP Microeconomics/Macroeconomics Premium, 2024: 4 Practice Tests + Comprehensive Review + Online PracticeNo ratings yet

- These are the Plunderers: How Private Equity Runs—and Wrecks—AmericaFrom EverandThese are the Plunderers: How Private Equity Runs—and Wrecks—AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (14)

- The New Elite: Inside the Minds of the Truly WealthyFrom EverandThe New Elite: Inside the Minds of the Truly WealthyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- Economics 101: From Consumer Behavior to Competitive Markets—Everything You Need to Know About EconomicsFrom EverandEconomics 101: From Consumer Behavior to Competitive Markets—Everything You Need to Know About EconomicsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Nudge: The Final Edition: Improving Decisions About Money, Health, And The EnvironmentFrom EverandNudge: The Final Edition: Improving Decisions About Money, Health, And The EnvironmentRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (92)

- Vulture Capitalism: Corporate Crimes, Backdoor Bailouts, and the Death of FreedomFrom EverandVulture Capitalism: Corporate Crimes, Backdoor Bailouts, and the Death of FreedomNo ratings yet