Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A

Uploaded by

Gyokushō HanzaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A

Uploaded by

Gyokushō HanzaCopyright:

Available Formats

Part Three: Discipline Docile bodies In the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the disciplines became

general formulas of domination (137): -- Working the body at the level of movements, gestures, attitudes: an infinitesimal power over the active body -- Object was the efficiency of movements, their internal organization -- Uninterrupted, constant coercion, supervising the processes of the activity rather than its result; exercised according to a codification that partitions time, space, movement as closely as possible. Discipline produces subjected and practiced bodies, docile bodies. Discipline increases the forces of the body (in economic terms of utility) and diminishes these same forces (in political terms of obedience). In short, it dissociates power from the body; on the one hand, it turns it into an aptitude, a capacity, which it seeks to increase; on the other hand, it reverses the course of the energy, the power that might result from it, and turns it into a relation of strict subjection. If economic exploitation separates the force and the product of labour, let us say that disciplinary coercion establishes in the body the constricting link between an increased aptitude and an increased domination (138). Small acts of cunning endowed with a great power of diffusion, subtle arrangements, apparently innocent, but profoundly suspicious, mechanisms that obeyed economies too shameful to be acknowledged, or pursued petty forms of coercion it was nevertheless they that brought about the mutation of the punitive system (139). No detail is unimportant, but not so much for the meaning that it conceals within it as for the hold it provides for the power that wishes to seize it (140). A meticulous observation of detail, and at the same time a political awareness of these small things, for the control and use of men, emerge through the classical age bearing with them a whole set of techniques, a whole corpus of methods and knowledge, descriptions, plans, and data. And from such trifles, no doubt, the man of modern humanism was born (141). The art of distributions Discipline proceeds from the distribution of individuals in space, which employs the following techniques: (1) Enclosure a place heterogeneous to all others and closed in upon itself, e.g., the monastery, army barracks, factories (2) Partitioning each individual has his own place and each place its individual, e.g., the monastic cell (3) Functional sites space that allowed supervision, disabled communication between individuals, and was useful (4) Rank the place one occupies in a classification. Ones distribution and circulation in relation to others. The table: in the form of disciplinary distribution, it distributes multiplicity and derives as many effects from it as possible. Disciplinary tactics are situated on the axis that links the singular and the multiple. It allows the characterization of the individual as individual and the ordering of a given multiplicity (149). The control of activity (1) The time-table (a general framework for activity, increasing partitioning of time, attempt to insure the quality of time [eliminate distractions and disturbances], how to constitute a totally useful time?) (2) Temporal elaboration of the act (a collective and obligatory rhythm, assures the elaboration of the act itself, controls its development and its stages from the inside. The act is broken down into its elements; the position of the body, limbs, articulations is defined; to each movement are assigned a direction, an aptitude, a duration; their order of succession is prescribed [152]) (3) Correlation of the body and the gesture (imposes the best relation between a gesture and the overall position of the body, which is its condition of efficiency and speech) (4) Body-object articulation (defines each of the relations that the body must have with the object that it manipulates) (5) Exhaustive use (the question of extracting from time more available moments and more useful forces) The organization of geneses How can one organize profitable durations? The disciplines, which analyse space, break up and rearrange activities, must also be understood as machinery for adding up and capitalizing time: (1) Divide duration into successive or parallel segments, each of which must end at a specific time (2) Organize threads according to an analytical plan successions of elements as simple as possible, combining according to increasing complexity (3) Finalize these temporal segments, decide on how long each will last and conclude it with an exam, which will have the triple function of showing whether the subject has reached the level required, of guaranteeing that each subject undergoes the same apprenticeship and of differentiating the abilities of each individual. (4) Draw up series of series; lay down for each individual, according to his rank, etc., the exercises that are suited to him. This is an exercise: the technique by which one imposes on the body tasks that are both repetitive and different, but always graduated. By bending behaviour towards a terminal state, exercise makes possible a perpetual characterization of the individual either in relation to this term, in relation to other individuals, or in relation to a type of itinerary. It thus assures, in the form of continuity and constraint, a growth, an observation, a qualification. Exercise, having become an element in the political technology of the body and of duration, does not culminate in a beyond, but tends towards a subjection that has never reached its limit (162). The composition of forces How to compose a force greater than the sum of its parts? This demand is expressed in the following ways: (1) The body is constituted as a part of a multisegmentary machine. (2) The chronological series that discipline must combine to form a composite time are also pieces of machinery.

(3) The combination of forces requires a precise system of command. Forces must react to signals as triggers. Discipline creates out of the bodies it controls . . .an individuality endowed with four characteristics: it is cellular (by the play of spatial distribution), organic (by the coding of activities), genetic (by the accumulation of time), combinatory (by the composition of forces). And in doing so, it operates four great techniques: it draws up tables: it prescribes movements; it imposes exercises; lastly, in order to obtain the combination of forces, it arranges tactics (167). Part III, ch 2 Foucault begins his discussion of the coercion of bodies (169) by informing us that [T]he chief function of the disciplinary power is to train. Instead of bending all its subjects into a single uniform mass, it separates, analyzes, differentiates, carries its procedures of decomposition to the point of necessary and sufficient single unitsDiscipline makes individuals; it is the specific technique of a power that regards individuals both as objects and as instruments of its exercise. This is the beginning of the invasion of the great forms and mechanisms of the sovereign or state by disciplinary power in the form of humble modalities Foucault considers three simple instruments of disciplinary power: hierarchical observation (pp. 170-177) normalizing judgement and (pp. 177-184) the examination (pp. 184-192) Hierarchical Observation The exercise of discipline presupposes a mechanism that coerces by means of observation (170). [T]he means of coercion make those on whom they are applied clearly visible, and improvements on technology increased the potential for observation (171). Foucault gives a description of a military camp as both an example of a power that acts by means of general visibility and as a model of principles found in urban development, in the construction of working-class housing estates, hospitals, asylums, prisons, schools: the spatial nesting of hierarchized surveillance (171-72). Structures of this sort, including hospitals, were designed with at least as great a concern for controlling the people and spaces it contained as for external considerations (172). The Ecole Militaire, for instance, was designed to allow for observation of students in their quarters, during meals, and in the latrine. A more continuous power is achieved through the establishment of a perfect eye that nothing would escape and a centre towards which all gazes would be turned, as was attempted in the Arc-et-Senans (173) with its circular structure. Pyramid structures were found to be even more effective for their ability to allow for relays and to 1: form an uninterrupted network with the possibility of multiplying its levels; 2: be discreet enough to keep from preventing the operations of the structure (174). As is the case in the industrial factory, where, according to the reasoning of the powerful, any dishonesty is apt to be multiplied and could prove fatal (175). Thus the guild-style system of management by masters was replaced by management by company agents. Surveillance thus becomes a decisive economic operator both as an internal part of the production machinery and as a specific mechanism in the disciplinary power (175). Foucault continues on to elementary teaching where the details of surveillance were specified and it was integrated into the teaching relationship (175) through careful monitoring, and, later, in the case of Demia, the use of teaching assistants. Demias model is presented as an institution of the mutual type in which Teaching proper, the acquisition of knowledge, and observation (176). Foucault comments here on the ability of power to operate as an integrated system (176) which allows for both hierarchical and lateral practices of power that systemic and individual: Discipline makes possible the operation of a relational power that sustains itself by its own mechanism and which, for the spectacle of public events, substitutes the uninterrupted play of calculated gazesthe hold over the bodyis a power that seems all the less corporal in that it is more subtly physical (177). Normalizing Judgement (sic) 1. Here Foucault presents us with the role of judgment in juvenile settings, such as the orphanage of the Chevalier Paulet, where students held morning tribunals to mete out punishments to their peers, at which point he observes: At the heart of all disciplinary systems functions a small penal mechanism (177). The workshop, the school, the army were subject to a whole micro-penality of time...of activityof behaviorof speechof the bodyof sexuality (ellipses mark parenthetical examples by Foucault) resulting in a state in which one was always punishing and punishable. 2. Foucault warns us here that the punishment of discipline was not just that of a small-scale model of the court (178). Judgment was passed on those, student or soldier, who did not achieve or perform to the dictated level. These observable deficiencies resulted in both punishment and public relegation, in the case of the student, to the bench of the ignorant. In a disciplinary regime punishment involves a double juridico-natural reference (179). 3. Here Foucault argues that Disciplinary punishment, ostensibly, has the function of reducing gaps. It must therefore be essentially corrective (179): The demoted corporal must regain his rank, the failing student, work and rework a lesson. Disciplinary punishment is, in the main, isomorphic with obligation itself, as, To punish is to exercise (180). 4. Punishment here is seen as only one element of a double system (of) gratification-punishment which operates in the process of training and correction through the careful definition and bestowal of rewards (180). Foucault uses a typically illustrative example of students living in a micro-economy of privileges and impositions in the Christian Schools, where a transposition of the system of indulgences (basically, you could get out of catechism exercises by building up points) allowed for the continuous ranking of students between poles of good and bad. Here judgment was passed on more than an act. This knowledge of individuals judged/ranked the potential and value of the child. 5. Here Foucault exposes ranking and grading as means of punishment and reward through the example of the Ecole Militaires

four (and sometimes five) levels of achievement assessed by officers, teachers, and their assistants, based on the moral qualities of the pupils and on their universally recognized behavior, and visually registered through the use of various colors of epaulettes (and maybe sackcloth) (181-182). The reasoning was, apparently, that the lowest, most shamed, ranks existed only to disappear (182), that is, to work their way up the epaulette-al hierarchy. This served the purpose of both classifying and encouraging conformity, according to Foucault. As he puts it: the art of punishing, in the regime of disciplinary power, is aimed neither at expiation, nor even precisely at repression, but at the following: 1. It refers individual actions to a whole that is at once a field of comparison, a space of differentiation and the principle of a rule to be followed 2. It differentiates individuals from one another 3. It measures in quantitative terms and hierarchizes in terms of value the abilities, the level, the nature of individuals 4. It introducesthe constraint of a conformity that must be achieved. 5. It defines the abnormal (182-183) In short, it normalizes (183). Here Foucault contrasts the disciplinary to the judicial penality, which referenced laws and binaries of moralities not observed individuals and rankings. It is the penality of the norm that brought about modern penality, not advent of human sciences, etc (183). The Normal is perpetuated through institutions and manages to both homogenize (through conformity)and individualize (through ranks and assessments). Through measurement , the norm introducesall the shading of individual differences in a homogenized setting (184). The Examination The examination, according to Foucault, combines the techniques of an observing hierarchy and those of a normalizing judgment (184). After briefly lamenting the lack of pre-Foucault scholarship on this concept, the author offers the examples of the hospital (pp. 185-186), with its secularization and transformation into a place for observation, and the school (pp. 186-187), with its transformation into the pedagogical science of evaluating and ranking. Foucault then presents three linkages that examinations created between a certain type of the formation of knowledge and a certain from of the exercise of power (187): 1. The examination transformed the economy of visibility into the exercise of power (pp. 187-189) Here, through the example of Louis XIVs first military review, Foucault reminds us of the shift in visibility from the punisher to the punished and explains that the examination is the mechanism of objectification in which disciplinary power manifests its potency, essentially, by arranging objects. 2. The examination also introduces individuality into the field of documentation (pp. 189-191) The examination leaves behind it a whole meticulous archive, through the act of power writing. The transcription and fixing of norms allowed also for the continuous analysis of the individual and the application of a comparative system in which to place said individual. 3. The examination, surrounded by all its documentary techniques, makes each individual a case (pp. 191-192). Disciplinary power lowered the threshold of describable individuality and made of this description a means of control and method of domination whereby the case is no longer a set of circumstances but a documented individual. Disciplines, then, mark the moment when the reversal of the political axis of individualizationtakes place (192). Whereas in the feudal regime the practice and display of power made the powerful individual visible, in the disciplinary regimeindividualization is descending: as power becomes more anonymous and more functional, those on whom it is exercised tend to be more strongly individualized (193). Here Foucault makes the productive power of discipline explicit: We must cease once and for all to describe the effects of power in negative terms[P]ower produces; it produces reality; it produces domains of objects and rituals of truth, in short, the individual (194). How, then, he asks, could such power (be derived) from the petty machinations of discipline (194)? The answer:

Part III, ch 3: Panopticism Foucaults discussion of the Panopticon proper is preceded by the legacies of the plague and the leper (195-200). Plague control at the end of the 17th century prescribed the creation inspectors and the transformation of the home into an enclosed, segmented space, observed at every point, in which individuals were the objects of writing, observation, and power. Thus, the plague, symbol of all forms of confusion and disorder, was met by order and analytic power; those acts and individuals that fell outside of this discipline were contagions. Foucault contrasts the system of order established by the plague to the exclusionary, binary principals that defined the leper and the clean (my term). All the mechanisms of power that the modern individual is subjected to are composed of those two forms from which they distantly derive. Benthams Panopticon is the physical manifestation of these forms. In it (visuals are widely available on the Web), the prisoner, who occupies the periphery of the circular structure, is visible to the guards, and invisible to the other prisoners. Foucault contrasts this to the dungeon, which served to enclose, to deprive of light and to hide (200). The exposed inmate is is the object of information, never a subject in communication as one might be in a dungeon (200). In all settings, panopticism replaces crowds, and their collective effect[s] with collection[s] of separated individualities (201). Hence the major effect of the Panopticon: to induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power so that the effects are

continuous and internalized, and the practice of surveillance always a possibility (see p. 201 for more description and discussion). This machine for dissociating the see/being seen dyad can be operated by anyone, increasing the likelihood of, and anxiety regarding, observation (202). The houses of security were to be replaced by this house of certainty (202). The Panopticon was also a laboratory (203), a privileged place from experiments on men, and for analyzing with complete certainty the transformations that may be obtained from them (204). Where the plague-stricken town was simple model of mechanical control or exclusion, the Panopticon must be understood as a generalizable model of functioning; a way of defining power relations in terms of the everyday life of men applicable to hospitals, workshops, schools, and prisons (205). It is numerically efficient, continuously able to intervene yet never needing to, and acts directly on individuals (206) regardless of scale. Lest we get too caught up in his machine metaphor, Foucault warns us that the exercise of power takes place within the machine; power the Panopticon is a way of making power relations function in a function, and of making a function through these power relations (206-207). This interior/exterior distinction gets a bit fuzzy when he goes on to discuss the Panopticon as open to the outsiders who would take part in observation: it has become a transparent building in which the exercise of power may be supervised by society as a whole (207). This seeming democratization of power is key to its being applied in the name of progress (208). This transformation from the discipline-blockade to the discipline mechanism was born in the rise of disciplinary thought in the 17th-18th centuries and concrete applications became models for entire disciplines. The spread of disciplinary institutions is likened to other more profound processes, of which this spread is an aspect: 1. The functional inversion of the disciplines. (pp. 210-211) Whereas the roles of institutions were once defined in negative terms (neutralize, fix, avoid), disciplines function increasingly as techniques for making useful individuals. This utility led to their being associated with the most important, most central and most productive sectors of society (education, training, war-making). 2. The swarming of disciplinary mechanisms. (pp. 211-212) The methodologies of schools, hospitals, and other institutions came to be applied by these institutions on the communities and individuals around them. These institutions also became centers of observations for the societies around them, subverting the traditional power of the church. 3. The state control of the disciplinary mechanisms. (pp. 213-217) Here we are warned that the secularization of power and its shift from monarchic control, as with the police in Foucaults example, is not a complete shift of disciplinary functions to the state apparatus, as Discipline may be identified neither with an institution nor with an apparatus; it is a type of power, a modality for its exercise (215): one can speak of the formation of a disciplinary society[n]ot because the disciplinary modality of power has replaced all the others; but because it has infiltrated the others (216). Foucault sums-up the shift from the spectacle to the surveilled that is made concrete in Benthams Panopticon in a lyrical discussion on pp. 216-217, where we are reminded that this has been a shift from persons being repressed to individuals fabricated into a social order. On pages 218-228, Foucault locates [t]he formulation of disciplinary society in the context of a a number of broad historical processes (roughly three): 1. Economic processes (pp. 218-221) Disciplines try to define in relation to the (human) multiplicities a tactics of power that fulfills three criteria: lowest cost, maximized social power, and linkage to the output of the apparatuses within which it is exercised; in short to increase both the docility and the utility of all the elements of the system (218). In the 18th century, this shift was concurrent with mobile populations and increased production capacities. While the old economy of power was wont to use violence to achieve control, discipline attempted to adjust people and apparatuses in order to counter the advantages of number through regimentation (219-220). This brings us to something of a definition: discipline is the unitary technique by which the body is reduced as a political force at the least cost and maximized as a useful force. Not surprisingly, Foucault ties the rise of a capitalist economy to the proliferation of panoptic (?) power (221). 2. Juridico-political processes (pp.221-224) Panopticism is neither an extension of, or independent of juridico-political power (221-222). Panopticism works it coercive force on the formal systems, even as the rise of the middle class attempted to create a codified legal framework (222). Discipline acts as a counter-law and, through the minute disciplines, the panopticisms of every day works it subtle magic against the more obvious mechanisms of the juridico-political (223). This why the smallest techniques of discipline (those most associated with the body?) are experienced or perceived as most foundational (223). The prisons power to punish has become the power to observe, selectively prosecute, and train, not through the universal consciousness of the law in each juridical subject but through the infinitely minute web of panoptic techniques (224). 3. Scientific processes (224-228) By the 18th century, these techniques achieved a level at which the formation of knowledge and the increase of power regularly reinforce one another in a circular process. Within institutions, the growth of power could give rise to new knowledge or methodologies for control. Foucault refers to this as a double processan epistemological thaw (224). Foucault goes on to draw a parallel between disciplinary examination and judicial inquisition or investigation, noting the relationship between inquisition and the rise of empirical methods (225-226). While investigation in the empirical sciences have managed to become detached from its

politico-juridical model, the examination has not ( 227). Penal justice today is both inquisitorial and disciplinary. Where the justice of the (spectacular) Ancien Regime was at its extreme in the infinite segmentation of the body of the regicideThe ideal point of penality today would be an indefinite discipline; an interrogation without enda procedure that would bethe permanent measure of a gap in relation to an inaccessible norm and the asymptotic movement that strives to meet in infinity (227). The final sentence of Part III (p228) reads: Is it surprising that prisons resemble factories, schools, barracks, hospitals, which all resemble prisons? Part IV, ch 1. Complete and austere institutions The turn of the 18th and 19th centuries saw the rise of detention as the penalty par excellence (231). However, the birth of the prison was marked by conjunction of a justice that is supposed to be equal and a legal machinery that is supposed to be autonomous, but which contains all the asymmetries of disciplinary subjection (231-232). Foucault laments that the concept of the prison has since become so naturalized that alternatives seem unthinkable. It even seems to be an egalitarian punishment in that time is assessed as opposed to fine in reparation for an offense against society. Foucault intends to further investigate the transformative role of the prison, and he cautions us to remember that the prison has been, from its beginnings in the 19th century, a means of both deprivation of liberty and the technical transformation of individuals (233), and he cites numerous sources to support the importance of the latter. He also argues that prison reform has been around for as long as prisons have, and that said reforms are a part of the penal process, not an interruption of it (234-235), and that in becoming a legal punishment, (the prison) weighted the old juridico-political question of the right to punish with all the problems, all the agitations that have surrounded the corrective technologies of the individual (235). Foucault draws the chapter title, complete and austere institutions, from an L. Baltard (pub. 1829; see Bibliography) in order to portray the exhaustive, uninterrupted, and despotic disciplinary power of the prison (235-236), which was to be applied to the reeducation and recoding of existence of the prisoner. This is contrasted with simple detainment and the simple mechanism of exempla imagined by the reformers at the time of the idealogues (236). He lays out the principles of the disciplinary prison as follows: 1. Isolation: He finds three primary reasons or functions for isolation: to prevent collaboration and recidivism, to promote reformatory practice, and to create a situation in which the words and power of the imprisoning and reforming power will take on even greater authority due to the relative silence of all others (236-237). He then contrasts the Auburn and Pennsylvania models for prisons, which posited limited interaction with other prisoners while working (reproducing exterior labor conditions) and utter solitude, respectively (237-239). 2. Work: Through numerous citations, Foucault pursues the question of the role of work in the prisons. Long-running debates in France pitted those who considered prison labor to be a magnet for the indigent and competition for the free laborer against a penal system that argued that prison labor offered little to no competition and that prisoners work and wages were their incentive for reform. Foucault takes a third position: that prison labor was about the constitution of a power relation (pp. 239-243). 3. The Declaration of Carceral Independence (247): Prison [became] increasingly an instrument for the modulation of the penalty; and apparatus which, through the execution of the sentence with which it is entrusted, seems to have the right, in part at least, to assume its principle (244). In assuming the responsibility for the means and extent of punishment and reform, the prison claims the right to be a power that not only possesses administrative autonomy, but is also a part of punitive sovereignty (247). The above techniques, to the extent that they exceed the state of detention, then, are to be know as the penitentiary (248). The penitentiary, Foucault argues, became a trap not only for prisoners, but for penal justice and judges, because it was able to introduce criminal justice into relations of knowledge that have since become its infinite labyrinth (249). The prisons observed not just for immediate control, but also to create a body of knowledge regarding the individual and his response to reformation in order to exact unceasingly form the inmate a body of knowledge that will make it possible to transform the penal measure into penitentiary operations (251). As the offender becomes an individual to know, a new character is created: that of the delinquent, who is characterized less by his act (offense) than by his life (251). For the re-education of the prisoner to be complete, the penitentiary operation must become the sum total existence of the delinquent, making of the prison a sort of artificial and coercive theatre in which his life will be examined from top to bottom (251-252). This biographical approach to understanding the delinquent establishes the criminal as existing before the crime and even outside it. This psycho-social concept of the dangerous individual is, according to Foucault, still with us today (252), and came to be categorized and documented, ultimately a biographical unity, a kernel of danger, representing a type of anomaly (254). The dangerous individual, or delinquent, is an amalgamation of 18th century prison objects: the extra-societal monster and the juridical subject rehabilitated by punishment (255).

Part IV, ch 2. Illegalities and delinquency Here Foucault begins with a discussion of the change from chain-gang to police carriage as a symptom and a symbol of the transition (or mutation) from the public display of power to the penality of prison (257). The chain gang of the turn of the century was a manifestation of both detention and public torture (255). Foucault paints a vivid picture of the dangerous, public applications of the chains and processions in which crowds participated in the spectacle as if in a festival or carnival, taunting and/or studying the condemned in what Foucault describes as part game, part ethnology of crime (259), in that the prisoner was the subject of speculation as much as spectacle. The chain-gang of early 19th century France, like the scaffold, was as dangerous as it was public however, and the crowd, as well as the prisoner, were able to apply meanings to the sentence and presence of the condemned that were not those intended or sanctioned by the judges (259-263). This means of transportation was replaced, in 1837, with a mobile equivalent of the panopticon, a cart in which detainees of all varieties were sequestered into cells, observable

by a center corridor by hidden from the view of the public, and prevented from interaction with one another, under constant surveillance and punishment by warders, and restricted to self-corrective thoughts and readings (263-264). The years 1820-1845 also saw a critique of the prison, according to Foucault, who cautions us against seeking to pat a timeline. He discusses five major critiques, which, we are told, are today repeated almost unchanged (265; as with previous discussions, Foucault cites 19th century sources throughout): 1. Detention causes recidivism (pp. 265-266): Foucault cites numerous arguments and figures regarding recidivism rates in support of his observation that prisons were producing delinquents, not corrected individuals. 2. Prisons produce delinquents by the very conditions (they) impose upon (their) inmates (266-267): Useless work, violent constraints, and various abuses of power are cited. 3. Prisons bring together delinquents who then collaborate with one another (267): Among his more memorable citations are references to prisons as settings for anti-social clubs and barracks of crime. 4. Ex-convict status and the markings and surveillance that come with it promotes recidivism 267-268). 5. [T]he prison indirectly produces delinquents by throwing the inmates family into destitution (268). The above critiques, addressed by claiming either a rudimentary state of corrective measures or that corrective measures detract from the ability to punish, were/are always rectified by the continued application of penitentiary technique: For a century and a half the prison had always been offered as its own remedy (268). In an explicit reference to current (early nineteen-seventies) conditions, he argues that there has been a continuous appeal to the seven universal maxims of the good penitential condition (for above, see 268-269; for items 1-7, pp. 269-270): 1. Penal detention must have as its essential function the transformation of the individuals behavior. 2. Convicts must be isolated or at least distributed according to the penal gravity of their act, but above all according to age, mental attitude, the technique of correction to be used, the stages of their transformation. 3. It must be possible to alter the penalties according to the individuality of the convicts, the results that have been obtained, progress or relapses. 4. Work must be one of the essential elements in the transformation and progressive socialization of convicts. 5. The education of the prisoner is for the authorities both an indispensable precaution in the interests of society and an obligation to the prisoner. 6. The Prison regime must, at least in part, be supervised and administered by a specialized staff possessing the moral qualities and technical abilities required of educators. 7. Imprisonment must be followed by measures of supervision and assistance until the rehabilitation of the former prisoner is complete. These continuously resurfacing propositions, serve uphold Foucaults assertion that there is not a three-stage history of the prison, its failure, and reform, but a simultaneous system, a fourfold system made up of: the super-power (of)penitentiary rationality; auxiliary knowledge (or reproduction) of criminality; inverted efficiency; reform as isomorphicwith the disciplinary functioning of the prison the element of utopian duplication (271). This supposed failure is, then, one of the effects of powerwhich may be grouped together under the name of carceral system (271). Having established the failure(s) of the prison (272), Foucault moves on to argue that they, and the effects (particularly of marking or establishing the delinquent) have not been abandoned because the prison, and no doubt punishment in general, is not intended to eliminate offences, but rather to distinguish them, to distribute them, to use them;they tend to assimilate the transgression of the laws in a general tactics of subjection, creating an economy of illegalities (272). In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, popular illegalities began to develop according to new dimensionsintroduced by movements whichlinked together social conflicts, the struggles against the political regimes, the resistance to the movement of industrialization, the effects of economic rises. The development of the political dimension of the popular illegalities were based in local actions (273-274), the rejection of the law or other regulation as struggle against those who enacted them (274), and the increases in regulatory functions of those wielding political or economic authority leading to an increase in the occasions of offences by those who would otherwise have been within the law (273-275). This increased politicization is tied by Foucault t to the changing role of the working-class in 19th century France and he cites numerous sources in support of the class dissymmetry affecting the application of law and justice (276). Delinquency, as a form of illegality, again becomes a means by which to categorize, etc, on behalf of the carceral system (277). Foucault sums up: We have seen how the carceral system substituted the delinquent for the offender, and also superimposed upon juridical practice a whole horizon of possible knowledge all of which enables them to reinforce one another perpetually, to objectify the delinquency behind the offence, to solidify delinquency in the movement of illegalities (277). Why and how, then, he asks, does penality invest certain practices in a mechanism of punishment-reproduction? His first assertion is that by defining and controlling a criminal element, a more supervisable, manipulable group diffuses the possibility for more disruptive (political) illegalities (278-279). His second is that it is used as form of colonialism, even domestically; for instance as a mechanism for reaping the profits of prostitution and other illegalities (279-280). His third, the political use of delinquents as thugs or a clandestine police force in labor struggles in particular, all of which is made possible by surveillance and documentation in collaboration with the prison and judges (280-282). On pages 282-285 explores the biographies of Vidocq, cop

and criminal who ended the Shakespearian age when sovereignty confronted abomination in a single character (283) and Francois Lacenaire, fallen bourgeois criminal and cause celbre.

Foucault describes the production of delinquency as a continuously shifting process, as opposed to a result, in which the delinquents are separated from and made to be demonized by the rest of the lower class populations, particularly in relation to labor struggles. All of which is described as a whole tactic of confusion aimed at maintaining a permanent state of conflict (285286). This was supplemented by a patient attempt to portray the criminal as ever-present and everywhere to be feared in the newspapers and novels of the time. By the end of the nineteenth century, the workers newspapers were actively campaigning against penal labor (286-287). This position is modified a bit to recognize that workers newspapers didnt solely vilify the criminal, but blamed societal conditions for forcing the criminal into desperate measures. Foucault argues that even these observations fell short of recognizing delinquency from above...the source of misery and the principle of revolt for the poor (287). It is, apparently, the increase in workers as political prisoners that leads the reappraisal of penal justice and the tactic of the counter-fait divers, which portrayed the decadent bourgeoisie as the ever-present criminal (288). Foucault cites the Fourierists as the first to elaborate a political theory which...places a positive value on crime. He argues that they recognized not a criminal nature, but a play of forces which, according to the class to which individuals belong, will lead them to power or to prison (289). This, then was a recognition of penality as political tool and of the play of opposing forces in which the prols were caught (289-290). He moves then to a third figure, a thirteen year old featured by La Phalange who opposed to the discourse of the law that made him delinquent... the discourse of an illegality that remained resistant to these coercions and which revealed indiscipline in a systematically ambiguous manner as the disordered order of society and as the affirmation of inalienable rights (290). Through the boys dialogue with his sentencing judge the paper, and Foucault, discussed the violent split between the accused and society, between the society and system that renders the worker a slave. This discourse, which Foucault notes may not be representative of the discourse of the workers newspapers, as the precursor of the recognition of the political problem of delinquency and the most militant rejection of the law and the awareness of the bourgeois system of legality and illegality (292). Part IV, ch 3. The carceral Foucault chooses January 22, 1840, the date of the official opening of Mettray, as the date of completion of the carceral system (293). Mettray, a prison for the underage, he explains, is the disciplinary form at its most extreme, the model in which are concentrated all the coercive technologies of behavior: the family, the army, the workshop, the school, and the judicial model (293294). Here, the entire parapenal institution, which is created in order not to be a prison, culminates in the cell, on the walls of which are written in black letters: God sees you (294). The chiefs and their deputies at Mettray...were in a sense technicians of behavior: engineers of conduct, orthopaedists of individuality who produced controllable bodies through their training (294295). Foucault explicitly argues that Mettray produced inmates who would then become the technicians of control in the first training college pure discipline (295). At this time power-knowledge, upheld by psychiatry and the judicial apparatus, (normalized) the power of normalization, and made warders out of prisoners (296). It was the most famous of a whole series of institutions which, well beyond the frontiers of criminal law, constituted what one might call the carceral archipelago (297). This time, minors were ostensibly being protected from the prison, then, is the moment when, according to Foucault, penality escapes transcends the boundaries of the prison proper: The frontiers between confinement, judicial punishment and institutions of discipline, where were already blurred in the classical age, tended to disappear and to constitute a great carceral continuum that diffused penitentiary techniques into the most innocent disciplines (297). The carceral system came to include a wide variety of institutions that were ostensibly charitable or intended for the shelter and protection of the poor and the young, eventually, reaching all the disciplinary mechanisms that function throughout society (297-298). Foucault summarizes: We have seen that, in penal justice, the prison transformed the punitive procedure into a penitentiary technique; the carceral archipelago transported this technique from the penal institution to the entire social body (298). He then argues that there have been six key results: 1. Individuals crimes, sins, and conduct were no longer judged by separate criteria and in relation to separate criteria. Irregular behavior was no longer the offence, the attack on the common interest, it was the departure from the norm, the anomaly...the social enemy was transformed into a deviant, whose deviance was deemed infectious. The carceral network linked...the two long, multiple series of the punitive and the abnormal (pp. 298-300) 2. The carceral allows the recruitment of major delinquents and organizes...disciplinary careers. Penality and discipline in the 19th century produced both docility and delinquency. In panoptic society, there are no outlaws, only those held and controlled by the law and its mechanisms. The carceral archipelago assures...the formation of delinquency on the basis of subtle illegalities, the overlapping of the latter by the former and the establishment of a specified criminality (pp. 300-301). 3. The carceral system succeeds in making the power to punish natural and legitimate, in lowering at least the threshold of tolerance to penality. It plays the legal register of justice and the extra-legal register of discipline...against one another, masking the true violence of penality. Society and the prison now differ only in degree, and societal discipline (and the self policing it entails) is accepted as proper, even when applied to the mildest transgressions (pp. 301-303). 4. The carceral network has a great normative function, and the judges of normality are present everywhere (p. 304)

5. The real capture of the body and its perpetual observation have created the knowable man, the object-effect of ... domination-observation. Foucault implies a relationship between the rise of the human sciences and the penal process of powerknowledge (pp. 304-305). 6. The prison is deeply rooted in mechanisms and strategies of power. However, the prison is neither indispensable or unalterable. Foucault names two processes capable of exercising considerable restraint and transformation on the prison: 1) processes which (reduce) the utility...of a delinquency accommodated as a specific illegality, as when the levy on sexual pleasure is carried out more efficiently through the market than through the archaic hierarchy of prostitution; 2) The spread of and growth of mechanisms of normalization beyond the prison, which, Foucault argues, will soon make the specificity of the prison unnecessary. (pp. 305-306) Foucault closes with another passage from La Phalange, in relation to which he makes the books final points about the carceral city: 1. that at the center of this city...is a multiple network of diverse elements; 2. that the model of the carceral city is... a strategic distribution of elements of different natures and levels 3. that it is the court that is external and subordinate to the prison (and not vice versa) 4. that it is linked to a whole series of carceral mechanisms 5. that the above mechanisms are applied to transgression of production not of a central law 6. That ultimately what presides over all these mechanisms is not the unitary functioning of an apparatus or an institution, but the necessity of combat and the rules of strategy. (pp. 307-308) Foucault asks that we hear the distant roar of battle and begin our own studies of the power of normalization and the formation of knowledge in modern society for which he has provided a background (308).

Outline prepared by Gretchen Haas and Brian Okstad December 15, 2003

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- SEO Roadmap - Bayut & DubizzleDocument17 pagesSEO Roadmap - Bayut & Dubizzlebasel kotbNo ratings yet

- Population Viability Analysis Part ADocument3 pagesPopulation Viability Analysis Part ANguyễn Phương NgọcNo ratings yet

- Tutorials in Complex Photonic Media SPIE Press Monograph Vol PM194 PDFDocument729 pagesTutorials in Complex Photonic Media SPIE Press Monograph Vol PM194 PDFBadunoniNo ratings yet

- Zone Raiders (Sci Fi 28mm)Document49 pagesZone Raiders (Sci Fi 28mm)Burrps Burrpington100% (3)

- A Management and Leadership TheoriesDocument43 pagesA Management and Leadership TheoriesKrezielDulosEscobarNo ratings yet

- KFC 225 Installation ManualDocument2 pagesKFC 225 Installation Manualsunarya0% (1)

- God As CreatorDocument2 pagesGod As CreatorNeil MayorNo ratings yet

- 39 - Riyadhah Wasyamsi Waduhaha RevDocument13 pages39 - Riyadhah Wasyamsi Waduhaha RevZulkarnain Agung100% (18)

- Chargezoom Achieves PCI-DSS ComplianceDocument2 pagesChargezoom Achieves PCI-DSS CompliancePR.comNo ratings yet

- Why-Most Investors Are Mostly Wrong Most of The TimeDocument3 pagesWhy-Most Investors Are Mostly Wrong Most of The TimeBharat SahniNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document16 pagesChapter 2nannaNo ratings yet

- 2 Beginner 2nd GradeDocument12 pages2 Beginner 2nd GradesebNo ratings yet

- Verbal Reasoning TestDocument3 pagesVerbal Reasoning TesttagawoNo ratings yet

- The Old Man and The SeaDocument6 pagesThe Old Man and The Seahomeless_heartNo ratings yet

- Philippines My Beloved (Rough Translation by Lara)Document4 pagesPhilippines My Beloved (Rough Translation by Lara)ARLENE FERNANDEZNo ratings yet

- Paper 2Document8 pagesPaper 2Antony BrownNo ratings yet

- MC2 Sewing Patterns: Dressmaking Learning ModuleDocument91 pagesMC2 Sewing Patterns: Dressmaking Learning ModuleMargie JariñoNo ratings yet

- Book Review Leffel Cateura, Oil Painting SecretsDocument4 pagesBook Review Leffel Cateura, Oil Painting SecretsAnonymous H3kGwRFiENo ratings yet

- SWOT ANALYSIS - TitleDocument9 pagesSWOT ANALYSIS - TitleAlexis John Altona BetitaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10: Third Party Non-Signatories in English Arbitration LawDocument13 pagesChapter 10: Third Party Non-Signatories in English Arbitration LawBugMyNutsNo ratings yet

- Course Hand Out Comm. Skill BSC AgDocument2 pagesCourse Hand Out Comm. Skill BSC Agfarid khanNo ratings yet

- Fabre, Intro To Unfinished Quest of Richard WrightDocument9 pagesFabre, Intro To Unfinished Quest of Richard Wrightfive4booksNo ratings yet

- Worksheet WH QuestionsDocument1 pageWorksheet WH QuestionsFernEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Sample ProposalDocument2 pagesSample ProposaltoupieNo ratings yet

- Prinsip TriageDocument24 pagesPrinsip TriagePratama AfandyNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 2 Revised - Morgan LegrandDocument19 pagesLesson Plan 2 Revised - Morgan Legrandapi-540805523No ratings yet

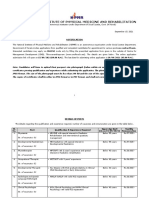

- NIPMR Notification v3Document3 pagesNIPMR Notification v3maneeshaNo ratings yet

- Calcutta Bill - Abhimanyug@Document2 pagesCalcutta Bill - Abhimanyug@abhimanyugirotraNo ratings yet

- Introductory EconomicsDocument22 pagesIntroductory Economicswedjefdbenmcve100% (1)

- Hardy-WeinbergEquilibriumSept2012 002 PDFDocument6 pagesHardy-WeinbergEquilibriumSept2012 002 PDFGuntur FaturachmanNo ratings yet